Abstract

Proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue offers significant diagnostic utility but is complicated due to the high level of covalently cross-linked proteins arising from formalin fixation. To address these challenges, we developed a reliable protein extraction method for FFPE tissue, based on heat-induced antigen retrieval within a pressure cooker. The protein extraction yield from archival FFPE tissue section is approximately 90% of that recovered from frozen tissue. This method demonstrates preservation of immuno-reactivity and recovery of full-length proteins by western blotting. Additionally we developed a well-based reverse-phase protein array platform utilizing an electrochemiluminescence detection system. Protein samples derived from FFPE tissue by means of laser capture dissection, with as few as 500 shots demonstrate measurable signal differences for different proteins. The lysates coated to the array plate, remain stable over 1 month at room temperature. Theses data suggest that this new protein-profiling platform coupled with the protein extraction method can be used for molecular profiling analysis in FFPE tissue, and contribute to the validation and development of biomarkers in clinical studies.

Keywords: Formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue, Laser capture microdissection, Protein extraction, Reverse-phase protein array, Tissue lysate

1 Introduction

Proteomic profiling of diseased and normal tissue promises to decipher proteomic complexities of the tissue microenvironment with pathologic and histologic relevance, and lead to the development of biomarkers to guide diagnosis and therapy in clinical environments. Numerous different approaches have been applied to this challenge [1–6], however reduction to widespread clinical utility has been problematic. Protein based arrays, either as antibody arrays, or “reverse-phase” arrays have appeal to the clinical medicine environment as they are functionally an extension of ELISA based methodologies, and offer direct measurement of the active biomolecules, rather than surrogates such as nucleic acid based assays. These technology possess great promise, however limitations are still unsolved and hinder protein microarray technology from reaching its full potential. These limitations include the cost of an array printers and the complexity of collecting and assaying all the samples at one time.

Formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue remains the gold standard of diagnostic histopathology and extraction of proteins remains a formidable challenge. Ikeda and colleagues [7] first described protein extraction from FFPE tissue in 1998. Different research groups have reported varying degrees of success by protein extraction from FFPE tissue section coupled with mass spectrum-or protein array-based quantification technology [6, 8–10]. For any protein array based platform to gain wide utility in tissue proteomics, it must be compatible with proteins extracted from these specimens.

Antibody arrays have well demonstrated utility; however, the efforts to match antibody affinities and binding conditions, as well as the dynamic range of proteins within tissue, have hindered this approach. “Reverse-phase” platforms overcome this obstacle by allowing dilution curves of lysates that can be then probed with individual antibodies under optimized assay conditions [11, 12]. Current “reverse-phase” platforms require sophisticated printers and complicated study designs where all the specimens to be assayed must be assembled at one time, preventing easy “assay on demand” environments. The dilution curves must be broad to be applicable to a wide range of protein concentrations and antibody affinities, consuming precious specimen. The arrays are difficult to store and require extensive antibody and assay validation, but demonstrate the significant potential of the general approach.

In this report, we describe a protein extraction methods based on detergents, extraction buffers and lysis conditions with FFPE tissue specimens. This method has merits of speed (the procedure can be completed within 1 hour), and high percentage recovery of full-length immuno-reactive proteins. Using the proteins extracted from FFPE tissue specimens, we developed a novel reverse-phase protein array platform, which can be applicable to routine clinical FFPE tissue specimens. This platform does not require a printer or arrayer and is applicable to “assay on demand” conditions. The arrays are stable for over a one month at room temperature. The new proteomic profiling method reported here has the potential to provide better insight into diseases and contribute toward development of clinically applicable biomarkers.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Tissue specimens

We utilized formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) human prostate tissues which have been stored at least 7 years at room temperature. The diagnosis was confirmed by histomorphologic examination. The archival tissue sections were obtained from the collection of the Tissue Array Research Program. The Office of Human Subject Protection of the National Institutes of Health approved collection and use of the tissue.

2.2 Antibodies and reagents

Anti-phospho-Akt, anti-AKT, anti-phospho-mTOR and anti-PTEN antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Berverly, MA). Anti-PSA and anti-smooth muscle actin antibodies were purchased from Dako (Carpentaria, CA). Anti-β-tubulin antibodies were obtained from Upstate Biotechnology (Charlottesville, VA). Anti-AMACR and anti-GAPDH antibodies were obtained from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). All detergents (SDS, NP-40, TritonX-100, CHAPS, CYMAL-7, octyl-D glucopyranoside and n-dentyl-β-D maloside) were purchased from Anatrace (Maumee, OH) or Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Silver staining kit was obtained from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ).

2.3 Protein extraction

Prior to protein extraction, twenty micrometer-thick FFPE tissue sections were trimmed of excess wax, and placed in a microcentrifuge tube. In order to establish a reliable protein extraction method, we examined lysis buffers, temperatures and times. We also tested deparaffinization effects and antigen retrieval effects for the optimal protein extraction method from archival FFPE tissue sections. Two hundred microliters of RIPA (1× PBS, 1% NP40, 0.5% deoxycholate), T-PER (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) or antigen retrieval buffers (pH 6.0 or 9.9, Dako) containing protease inhibitor (1 tablet/25ml, Roche) were added to each tube and then incubated under different conditions as follows: at 4°C for 3 h; at 25°C for 3 h; at 37°C for 3 h; at 65°C for 3 h with or without antigen retrieval pretreatment. We also tested pressure cooker effects under different conditions as follows: 5-, 10-, 15-, 30- and 60-min incubations at 100°C, 115°C or 124°C. In order to extract large amounts of protein from FFPE tissue sections, we evaluated the effects of 1 or 2% SDS, NP-40, TritonX-100, CHAPS, CYMAL-7, octyl-D glucopyranoside and n-dentyl-β-D maloside detergents. In addition, we further tested the impact on protein release from FFPE tissue sections using combinational detergents with SDS and Triton X-100. After comprehensive analysis of factors in protein extraction from FFPE tissue specimens, we arrived at a new protein recovery protocol from FFPE tissue. A twenty-micrometer-thick FFPE tissue section was trimmed of excess wax and homogenized using a Disposable Pellet Mixer in 200 μl protein extraction solution [1x high pH Antigen retrieval buffer (pH 9.9) (Dako), 1% NaN3, 1% SDS, 10% glycerol and protease inhibitor (1 tablet/25 ml, Roche)], followed by incubation for 15 min at 115°C within a pressure cooker(Dako) at 10 ~ 15 psi,. After incubation, the tissue lysates were centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C. For cell lines, total protein was extracted using RIPA buffer and sonicated. Total protein concentrations were measured with the BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology).

For laser capture microdissection experiments, sections were deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin, with xylene, subject to microdissection with an Arcturus Pixel II instrument using a 15 μm spot size. Captured cells were extracted off the cap with the above-described buffer in a total volume of 30 μl.

2.4 SDS-PAGE and western blotting

The protein extracts containing 20 μg of protein from FFPE tissue sections were subjected to 4–12% NuPAGE® Novex Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) for 1h, washed, and subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C in TBST with 5% BSA containing the following antibodies; anti-phospho AKT (1:200), anti-AMACR (1:500), anti-PSA (1:200), anti-GAPDH (1:1000), or anti-β-tubulin (1:1000). Specific molecules were detected with horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Chemicon International) and enhanced with SuperSignal Chemiluminescence kit (Pierce Biotechnology) or ECL kit (Amersham Biosciences). Signal was detected on KODAK BIOMAX MR X-ray film (Kodak). For reliable signal quantitation on the same blot, we used Re-Blot Plus stripping solution (Chemicon International) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Quantitative analysis of the western blotting was performed by analysis of the scanned X-ray films with ImageQuant (Ver. 5.2, Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

2.5 Novel reverse-phase protein array

Proteomic expression signals from archival FFPE tissue were also detected using Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) Multi-SpotTM plates (MA6000 96 HB Plate) and an MSD Sector Imager 6000 reader (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD). Five microliters of protein extract from FFPE tissue specimen at predetermined protein concentrations, were added to 96 well plates, the plate was allowed to dry at room temperature for 90 min, and the plates were subsequently further incubated at 37°C for 30min. The antigen-coated plates were preincubated with 5% BSA in PBST before incubation with specific antibodies at the same dilution as used in the western blots, (except PSA, which was used at 1:500) at 4°C for overnight. After washing with PBST, the plates were incubated for 1 h with goat anti-mouse SULFO-TAG™ antibodies at a dilution of 1:500 (1 μg/ml). The plates were then aspirated and washed three times with PBST. Finally, MSD-T read buffer was added to the plates and they were read on the Sector Imager 6000. To test the sensitivity and dynamic range, sequentially diluted protein extracts were analyzed by the MSD assay for PSA and GAPDH and the minimal concentration of detergent required was determined. In addition, BSA coated wells were included on each plate as a control for non-specific binding effects. The values from non-specific wells were subtracted from all standards samples to calculate actual value. In order to determine the stability of this immunoassay, we performed the MSD assay for PSA at 1-, 3-, 7-, 14-, 28-, and 56-day after protein coating.

3 Results

3.1 Protein extraction based on heat-induced AgR technology is facilitated by pressure and detergent

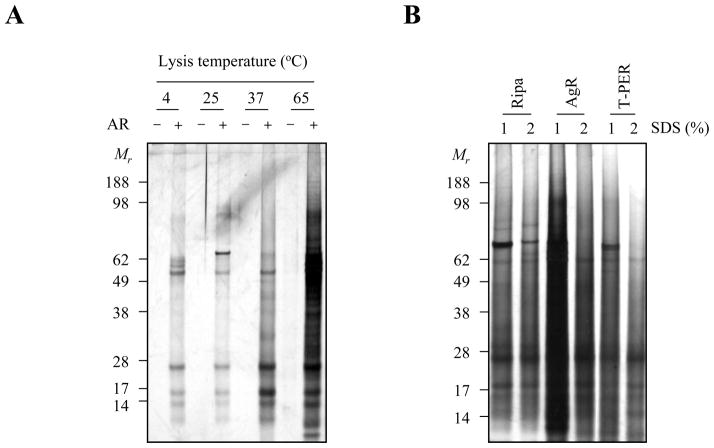

In order to establish a reliable protein extraction methodology that can be applied to proteomic profiling of routinely processed FFPE tissue specimen, we first examined the effects of lysis and antigen retrieval conditions. Figure 1 shows that protein extraction can be detected with incubation at 4°C, but improves with increased temperature, demonstrating a full spectrum of proteins in the tissue was extracted following 3 hours incubation at 65°C in RIPA buffer containing 1% SDS (Fig. 1A). We subsequently examined different extraction solutions containing 1 or 2 % SDS to improve protein recovery. Maximal protein recovery across a wide range of molecular weights was obtained with high temperature in Dako high pH Antigen Retrieval buffer (pH 9.9) with the addition of 1% SDS (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Protein extraction profiles based on lysis temperatures and extraction buffers. (A) The deparaffinized 20 μm-thick human prostate tissues were suspended in 200 μl of RIPA buffer containing 1% SDS and then incubated at 4°C, 25°C, 37°C and 65°C for 3 h with (+) or without (−)antigen retrieval pretreatment. (B) To examine the effects of different buffers, the tissue specimens were incubated in RIPA, antigen retrieval (AgR) buffer (pH 9.9) (DAKO) and T-PER buffers containing 1 or 2% SDS at 115°C for 15 min using a pressure cooker. Five microliter of protein extracts were separated in a 4–12 % NuPAGE® Novex Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel and then stained using silver staining kit according to the manufacture’s instruction. (AgR: antigen retrieval; Mr: protein molecular marker)

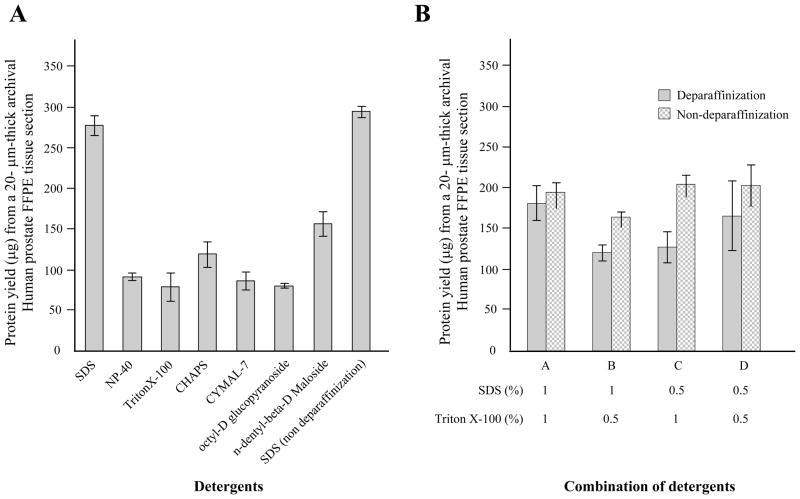

Next, we analyzed the impact of different detergents on the efficiency of protein recovery from FFPE tissue. Use of SDS resulted in the highest protein yield among tested detergents, regardless of deparaffinization (Fig. 2A). In addition, we examined a combination of SDS and Triton X-100 with or without deparaffinization. When compared to SDS detergent alone, there was no advantage in using a combination of detergents. Furthermore, the deparaffinization step was not an obligatory step for protein recovery from FFPE tissue (Fig. 2B). The difference in protein band pattern from each condition was negligible on SDS-PAGE as measured by silver staining (data not shown). The addition of 10% glycerol to the protein extraction buffer resulted in more consistent protein yield compare to the buffer without glycerol (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Impact of detergent on protein solubilization of archival human tissue specimen. Protein was extracted from a 20 μm-thick FFPE prostate specimen, under conditions of AgR (high pH) buffer containing 1% of specified detergent at 115°C for 15 min incubation within a pressure cooker (A) Protein yield was highest under conditions of 1% SDS in regardless of deparaffinization. (B) A combination detergent of SDS and Triton X-100 was less effective than the SDS single regimen for protein extraction from archival FFPE tissue sample. Deparaffinization and non-deparaffinization before incubation in lysis buffer were compared. The mixture ratio of SDS and Triton X-100 is designed at the bottom of the graph. The graph shows the average of protein yield which is presented as bars; average ± SD. (C) The improvement in consistency of extraction by the addition of glycerol is demonstrated by increased recovery and decreased variability as measured by the BCA protein assay, based on three independent extractions.

Overall, the AgR buffer containing 1% SDS combined with higher temperature (115°C) and moderate pressure (10–15 psi) resulted in a greater protein yield without change of quality of protein as measured by SDS-PAGE. Although the extracted protein showed a smearing pattern on SDS-PAGE, the lysate contained relatively broad range of molecular weight proteins ranging from 10 kDa to 180 kDa. The average total protein yield was 29.44 ± 7.8 μg per 1 mm3 of archival human FFPE tissue. We confirmed that the protein recovery yield from FFPE tissue was approximately 90% of that recovered from an equal volume of fresh tissue (data not shown).

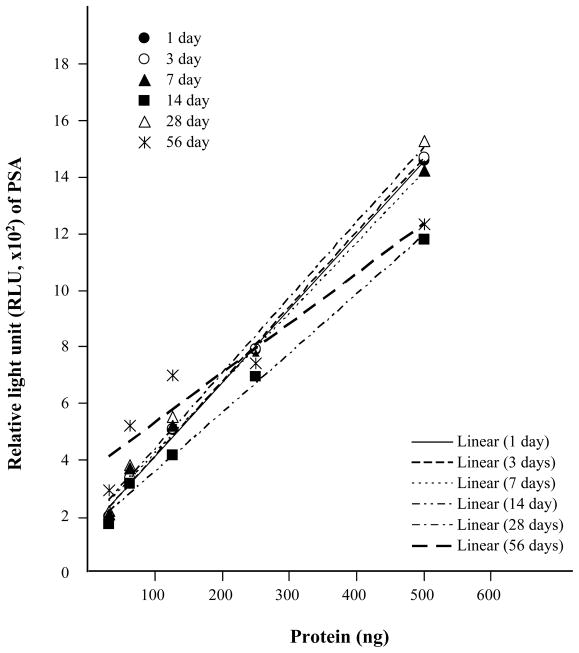

3.2 High quality of protein can be extracted from FFPE tissue

To assess protein quality and protein yield from routinely processed FFPE tissue, we examined immuno-reactivity of prostate tissue during a time-course from 5 to 60 min of antigen retrieval with anti-PSA antibodies and quantified the protein recovery yield from these conditions. The protein yield is increased with longer antigen retrieval time (Fig. 3A), however the protein quality is rapidly dropped after 30 min at 115°C within a pressure cooker (Fig. 3B). As shown figure 3, the protein band pattern is stabled up to 15 min incubation as demonstrated on SDS-PAGE by coomassie blue staining. In addition, the PSA signal from FFPE-protein extract from prostate tissue after 15 min incubation was approximately 80% of that probed from 5 min incubation (Fig. 3A). To optimize conditions for both protein quality and yield, we utilized a 15 min antigen retrieval time for the protein extraction protocol.

Figure 3.

FFPE-protein quality according to incubation time within a Pascal pressure cooker (Dako). A non-deparaffinized archival human prostate FFPE tissue section (20 μm-thick) was trimmed of excess wax and homogenized using a Disposable Pellet Mixer in 200 μl protein extraction solution (to see Materials & Methods), with incubation for 5-, 10-, 15-, 30- and 60-min at 115°C within a pressure cooker. (A) The FFPE-proteins were separated by 4–12% reducing SDS-PAGE (CBB staining), electroblotted to nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with anti-PSA antibodies (1:200). (B) The amount of protein extracted from each condition was measured using BCA Protein Assay Kit. The bar graph shows the relative averages of protein yield; average ± SD. Relative protein quality of each entity is normalized to 5 min incubation condition (1.00)

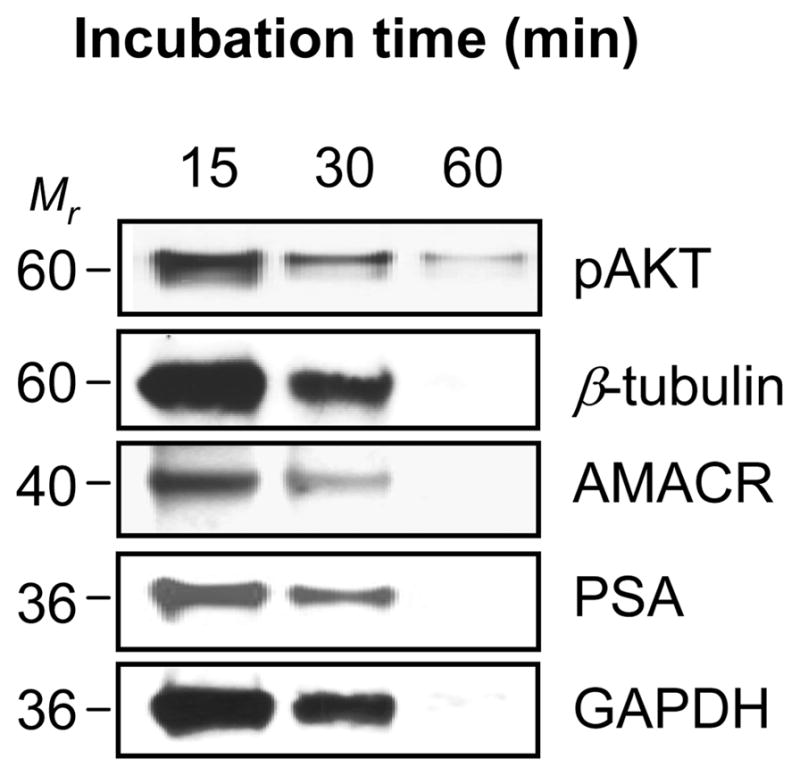

Next, we analyzed whether the expression signal of several molecular targets correlate with the predicted molecular weight on western blotting. Proteins extracted from archival human prostate FFPE tissue specimens contained high amounts of immuno-reactive proteins as demonstrated by western blotting, including pAKT, AMACR, PSA, β-tubulin and GAPDH (Fig. 4). We reconfirmed that the protein quality decreased according to longer incubation time whereas the protein recovery yield from the FFPE tissue increased with longer incubation at high temperature and pressure.

Figure 4.

Protein integrity of FFPE-derived protein by western blotting. FFPE-proteins were extracted from FFPE tissue specimen with 15-, 30- and 60-min incubation within a pressure cooker. 20 μg of FFPE-proteins were subjected to a 4–12% gradient polyacrylamide gel under reducing condition. After transfer to nitrocellulose membrane, the membrane was probed with anti-pAKT, anti-β-tubulin, anti-AMACR, anti-PSA and anti-GAPDH antibodies. The signal was detected with a SuperSignal Chemiluminescence kit (Mr: protein molecular marker).

3.3 Novel reverse-phase protein array is a reliable and stable high-throughput platform

Western blot analysis is inappropriate for routine clinical environments. It is relatively insensitive, requiring a large number of cells for analysis, lacks throughput, and has significant complications in quantitation. We therefore developed a novel reverse-phase protein array platform utilizing protein extracted from FFPE tissue. This new method primarily based on an electrochemiluminescence detection system using Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) technology. The basis of this approach is the determination of the protein concentration of lysates, creation of a dilution curve, and direct application of the diluted lysates to a rough carbon surface of the MSD plates. Lysates are allowed to dry, and proteins are detected by application of antibody of choice.

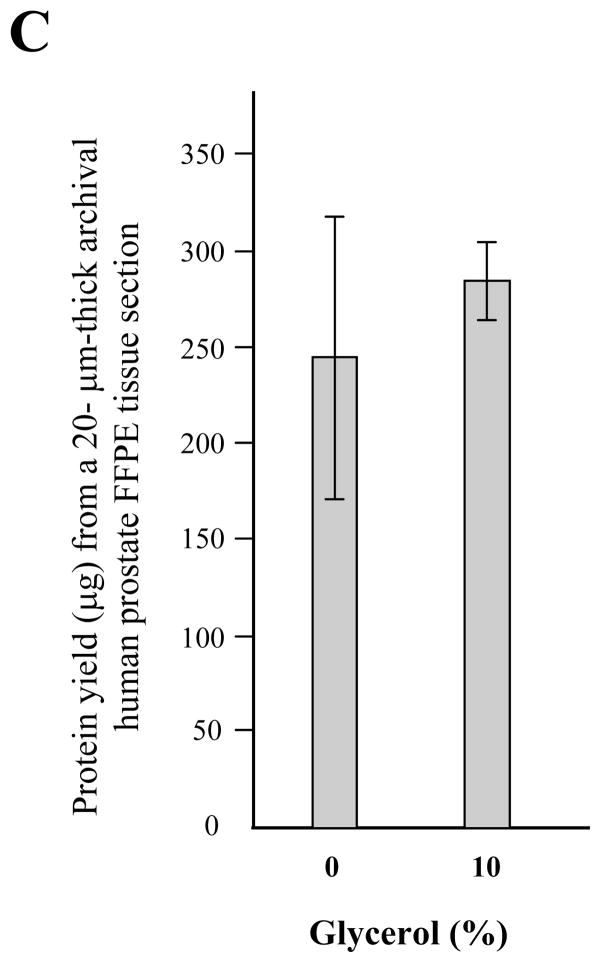

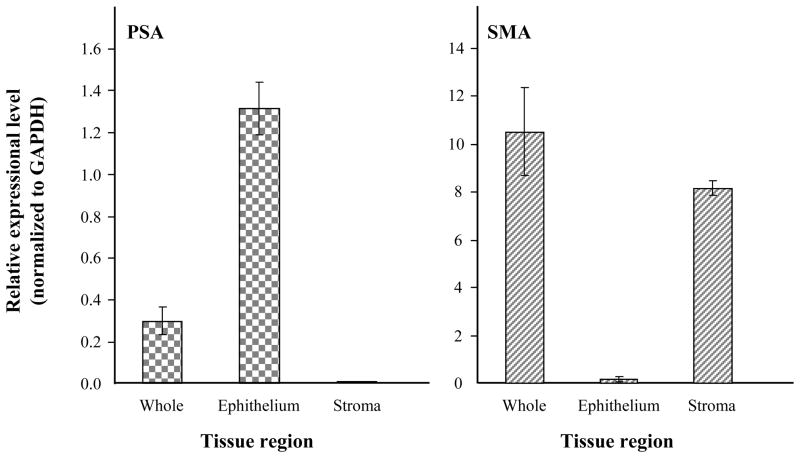

GAPDH expressional signal from FFPE tissue demonstrated strong correlation with amount of protein presented (R2 = 0.999 and 0.997 for cell lysate and FFPE tissue, respectively), In addition we subsequently confirmed high sensitivity and linearity of using anti-PSA antibody (R2 = 0.997), with dynamic range from 0.01 μg to 2.3 μg (Supplemental Fig. 1). To demonstrate the ability to measure specific proteins from FFPE tissue prepared by laser capture microdissection (LCM), 10 μm-thick prostate tissue section was deparaffinized and then stained with hematoxylin only. Five hundred shots (15 μm diameter laser beam) were microdissected from each epithelium and stromal region within the stained prostate tissue section using the PixCell II LCM system (Arcturus). Protein extraction from LCM sample was successful, with average total protein yield 3.38 ± 1.2 μg per 500 shots. We performed the new reverse-phase protein array using 500 ng of the protein extracts against PSA, smooth muscle actin and GAPDH. As confirmed by western blotting (section 3.2), the protein extracted from LCM prostate FFPE tissue specimen contained significant amounts of immuno-reactive proteins (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Protein expression profiling by a novel reverse-phase protein array platform using LCM sample. 500 shots (15-μm diameter laser beam) each of epithelial and stroma were microdissected from a 10 μm-thick prostate hematoxylin stained FFPE tissue. Protein extracted from an adjacent whole section of the same prostate FFPE tissue block was also included in this assay. The new reverse-phase protein arrays using 500 ng extracted protein per well was performed. Primary antibodies were diluted 1:500 (PSA) or 1:1000 (smooth muscle action & GAPDH) with 3% BSA. After normalization with GAPDH level, Relative expressional signals were represented as ratio. The bar graph shows the average ± SD of three replicated wells.

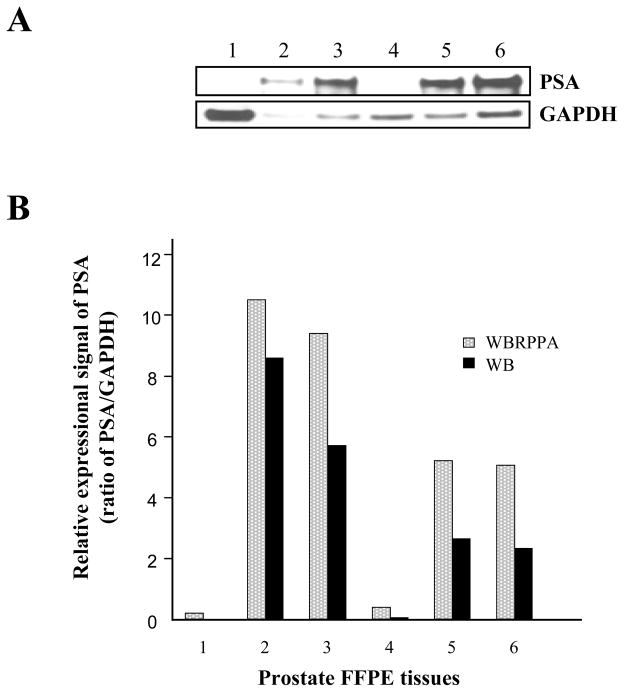

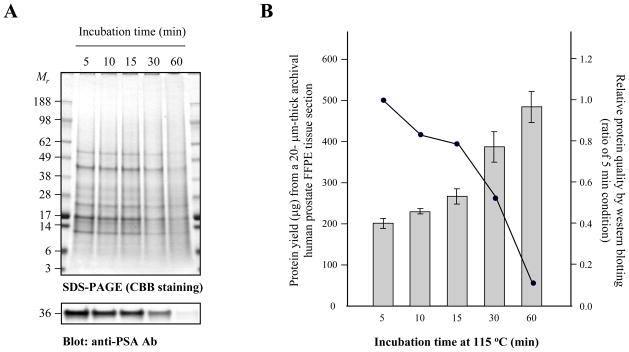

With these encouraging findings, we further analyzed whether the expression signal from the western blots (Fig. 6A) correlated with data from our platform technology (Fig. 6B). As shown Fig 6, relative PSA signals in series of prostate tissues were measured and the ratio of PSA to GAPDH was calculated. The signal in the well-based reverse-phase protein array (WBRPPA) correlate with that of western blots (R2 = 0.931) (Fig. 6C), and had greater sensitivity. These data suggest that this methodology could be used for proteomic profiling within FFPE tissue specimen, with advantages of high throughput, and small starting material requirements. Having refined the reverse phase protein array, we measured five different markers on a number of prostate tissue specimens as a general proof of principle that the method could be applied to routine clinical specimens (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Figure 6.

Comparison of protein profiling between novel reverse phase protein array and western blotting. In order to compare results of novel reverse-phase protein array versus western blotting, we extracted total proteins from 6 different prostate FFPE tissue specimens. (A) The specimens showed a variable PSA expression pattern. For reliable signal quantitation on same blot, we re-probed the membrane with anti-GAPDH antibodies. Quantative analysis was performed using the ImageQuant program. (B) PSA and GAPDH expressional signals from different six specimens were measured using novel well-based reverse-phase protein array (WBRPPA). Relative expressional signal of PSA was displayed as a ratio of PSA to GAPDH. Light bar and black bar represent results of novel WBRPPA and western blotting (WB), respectively. (C) The signals in western blots and novel reverse-phase protein arrays were strongly correlated (for PSA: R2 = 0.93).

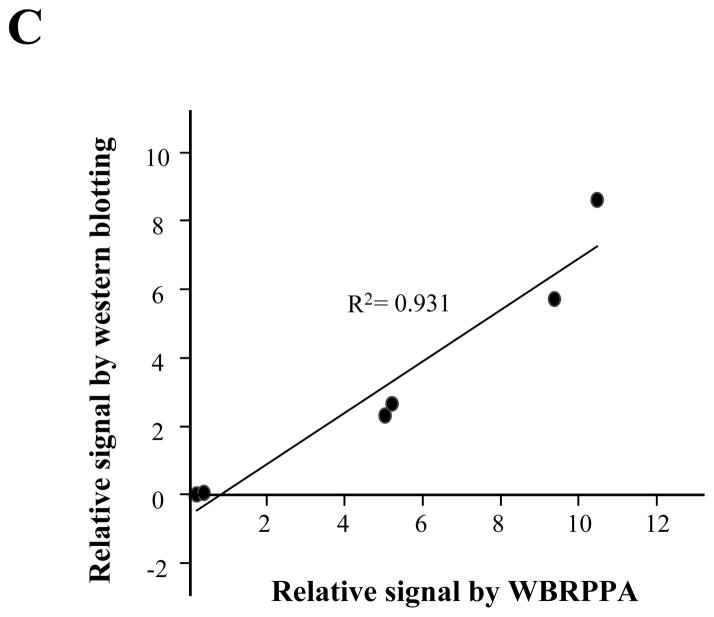

To determine the reliability and stability of WBRPPA, we stored vacuum-sealed 96 well plates at RT after protein coating, and monitored PSA signal over 2 months. The PSA signal in protein extracted from archival prostate FFPE tissue was relatively stable up to 2 months at dynamic range with minor degradation in linearity at 8 weeks (Fig. 7), indicating that a well based phase protein array could be prepared and stored for a reasonable duration before application of antibody.

Figure 7.

Stability of a novel reverse-phase protein array platform. In order to examine the stability of new reverse-phase protein array platform using FFPE-proteins, we stored the vacuum-sealed 96 well plate at RT after protein coating, and measured PSA signal over 2 months (1, 3, 7, 14, 28, and 56 days, R2 ≥ 0.93). Dynamic ranges in plot are based on the standard curve; results given are the mean of three replicated wells.

4 Discussion

Global analysis of genomes and transcriptomes, enabled by nucleic acid microarrays, has altered the manner in which biomedical research is carried out. Subsequently, a strong interest has emerged in analyzing the function of the proteome on a similarly global scale. However, the analysis of the proteome is more complex than that of nucleic acids because of the cascade processes such as posttranscriptional control of protein translation [13], a number of posttranslational modifications of protein [14], and protein degradation by proteolysis [15]. This situation is additionally complicated by the fact that no function is ascribed to more than 75% of the predicted proteins of multicellular organisms [16]. These issues as well as the poor correlation between mRNA and protein expression levels [17–19], suggest that knowledge of genomic sequences and transcriptional profiles have limitations as surrogates for cellular activity mediated by proteins, and that direct measurement of proteins may provide better biomarkers of disease.

Biomarkers from tissue-based proteomic studies directly contribute to defining disease states as well promise to improve early detection and provide enable personalized therapeutics. Although frozen human tissues have been used as starting material for many proteomic studies, obtaining and handling such tissue sample outside of the research setting is a challenge. In the clinical setting, tissue samples are preserved as formalin fixed and paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks for histological examination. Large-scale validation of candidate tissue biomarkers is impractical on anything other than FFPE tissue.

However, protein extraction from FFPE tissue remains a major concern [20]. Recent advances in techniques for extracting proteins from FFPE tissue sections have been facilitated tissue protein profiling in the clinical proteomics, with varying degree of success [7, 9, 21–23]. These approaches are based on the principal of the application of heat to a detergent containing solution, and frequently require relatively high concentrations of detergent, large amounts of starting material and are time consuming. In addition, previous studies did not verify a high yield of protein extraction or correlation data between western blots and other proteomic methods. We demonstrate that our method results in good protein extraction yield from relatively small amounts of materials, with relatively low concentration of detergent and regardless of the deparaffinization step (Fig. 2). We successfully detected five different targets using monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies by western blots, suggesting that proteins extracted from FFPE tissue section contain non-degraded immuno-reactive molecules. Our method has the advantage of being compatible with archival tissue and permitting the use of phospho-specific antibodies. The characteristics of the proteins extracted from FFPE tissue section are similar to that of frozen tissue, with a similar protein band pattern on SDS-PAGE except for smearing in FFPE sample. We are investigating factors that impact the recovery of full length of the proteins. It appears the quality of the protein is largely a function of the tissue handling and processing conditions, however the FFPE-protein extracted by our method is a comparable to that of frozen tissue. Recently, Becker et al. [10] reported a successful protein extraction from FFPE tissue using the QProteome kit (Qiagen). Although they succeeded in isolating relatively high protein extraction yield and non-degraded immuno-reactive proteins, the authors did not test limitation of starting materials for their extraction method. The use of small amounts of starting material has a great significance in clinical proteomics research as it allows research on the frontiers of oncology, for example smaller breast tumors. We applied our method to LCM samples in order to determine minimum of starting material. Our method has yielded 3.38 ± 1.2 μg proteins from 500 shots prepared by LCM, with a 10 μm hematoxylin stained FFPE tissue section.

In order to perform tissue protein profiling with high throughput mode we developed a novel reverse-phase protein array using protein extracted from FFPE tissue section. We applied the FFPE-protein directly to carbon-coated plates suitable for the electrochemiluminescence detection system, with an advantage of great sensitivity. We have confirmed the sensitivity that the assay can detect multiple markers using 10 or fewer cells when applied to fresh cell lines (data not shown). The well-based reverse phase protein microarray based on the combined approach of a new protein extraction methodology and MSD technology, does not require sophisticate fabrication procedures and extensive dilution curves as current reverse-phase protein microarrays. In addition, the assay can easily detect signals of high molecular weight proteins that are difficult to detect by western blotting (Supplemental Fig. 1C & D). This data suggests that the assay can be applied to the routine clinical specimens because the method overcome the disqualified protein problem resulted from over-crosslinking. Once an assay is developed, it is only necessary to apply sufficient lysates for detection within the linear range of the assay. The assay platform is stable up to 2 months at room temperature under vacuum-sealed condition, offering great abilities for antibody affinity validation and alleviating complex study design. We successfully tested three different antibodies using protein extracted from FFPE LCM samples (500 shots) with a multiplex fashion (Fig. 5).

In conclusion, this approach of a robust isolation methodology paired with a novel well-based electrochemiluminesence detection method should provide a powerful tool for tissue protein analysis and profiling. The approach is directly applicable to FFPE tissue, and presents the direct opportunity of addressing hypothesis within clinical trials and well-annotated clinical tissue repositories [24, 25]. When applied to LCM sample, it offers great potential to facilitate discovery and development of new diagnostic assays and therapeutic targets in clinical proteomics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Abbreviations

- AgR

antigen retrieval

- AMACR

alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase

- CBB

Coomassie brilliant blue G250

- FFPE

formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded tissue

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- WBRPPA

well-based reverse-phase protein array

References

- 1.Letarte M, Voulgaraki D, Hatherley D, Foster-Cuevas M, et al. Analysis of leukocyte membrane protein interactions using protein microarrays. BMC Biochem. 2005;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schweitzer B, Predki P, Snyder M. Microarrays to characterize protein interactions on a whole-proteome scale. Proteomics. 2003;3:2190–2199. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson WH, DiGennaro C, Hueber W, Haab BB, et al. Autoantigen microarrays for multiplex characterization of autoantibody responses. Nat Med. 2002;8:295–301. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lueking A, Possling A, Huber O, Beveridge A, et al. A nonredundant human protein chip for antibody screening and serum profiling. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:1342–1349. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T300001-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Wildt RM, Mundy CR, Gorick BD, Tomlinson IM. Antibody arrays for high-throughput screening of antibody-antigen interactions. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:989–994. doi: 10.1038/79494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caldwell RL, Callister SJ. Tissue profiling by mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:394–401. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R500006-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeda K, Monden T, Kanoh T, Tsujie M, et al. Extraction and analysis of diagnostically useful proteins from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:397–403. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hood BL, Darfler MM, Guiel TG, Furusato B, et al. Proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed prostate cancer tissue. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1741–1753. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500102-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi SR, Liu C, Balgley BM, Lee C, et al. Protein extraction from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections: quality evaluation by mass spectrometry. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:739–743. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5B6851.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker KF, Schott C, Hipp S, Metzger V, et al. Quantitative protein analysis from formalin-fixed tissues: implications for translational clinical research and nanoscale molecular diagnosis. J Pathol. 2007;211:370–378. doi: 10.1002/path.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paweletz CP, Charboneau L, Bichsel VE, Simone NL, et al. Reverse phase protein microarrays which capture disease progression show activation of pro-survival pathways at the cancer invasion front. Oncogene. 2001;20:1981–1989. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grubb RL, Calvert VS, Wulkuhle JD, Paweletz CP, et al. Signal pathway profiling of prostate cancer using reverse phase protein arrays. Proteomics. 2003;3:2142–2146. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy JE. Posttranscriptional control of gene expression in yeast. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1492–1553. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1492-1553.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parekh RB, Rohlff C. Post-translational modification of proteins and the discovery of new medicine. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1997;8:718–723. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(97)80126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcotte EM. Measuring the dynamics of the proteome. Genome Res. 2001;11:191–193. doi: 10.1101/gr.178301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edward AM, Arrowsmith CH, des Palliers B. Proteomics: new tools for new era. Modern Drug Discovery. 2000;5:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson L, Seilhamer JA. Comparison of selected mRNA and protein abundances in human liver. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:533–527. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin TJ, Gygi SP, Ideker T, Rist B, et al. Complementary profiling of gene expression at the transcriptome and proteome levels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:323–333. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200001-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ideker T, Thorsson V, Ranish JA, Christmas R, et al. Integrated genomic and proteomic analyses of a systematically perturbed metabolic network. Science. 2001;292:929–934. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5518.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaurand P, Norris JL, Cornett DS, Mobley JA, Caprioli RM. New developments in profiling and imaging of proteins from tissue sections by MALDI mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:2889–2900. doi: 10.1021/pr060346u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu WS, Liang Q, Liu J, Wei MQ, et al. A nondestructive molecule extraction method allowing morphological and molecular analyses using a single tissue section. Lab Invest. 2005;85:1416–1428. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prieto DA, Hood BL, Darfler MM, Guiel TG, et al. Liquid Tissue TM: proteomic profiling of formalin-fixed tissues. Biotechniques. 2005;38:S32–S35. doi: 10.2144/05386su06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamashita S, Okada Y. Mechanisms of heat-induced antigen retrieval: analyses in vitro employing SDS-PAGE immunohistochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:13–21. doi: 10.1177/002215540505300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis F, Maughan NJ, Smith V, Hillan K, Quirke P. Unlocking the archive--gene expression in paraffin-embedded tissue. J Pathol. 2001;195:66–71. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(200109)195:1<66::AID-PATH921>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung JY, Braunschweig T, Baibakov G, Galperin M, et al. Transfer and multiplex immunoblotting of a paraffin embedded tissue. Proteomics. 2006;6:767–774. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.