Summary

The Leucine-rich repeat-containing, G protein coupled receptors (Lgrs) are a large membrane protein family mediating signaling events during development and in the adult organism. Type 2 Lgrs, including Lgr4, Lgr5 and Lgr6, play crucial roles in embryonic development and in several cancers. They also regulate adult stem cell maintenance via direct association with proteins in the Wnt signaling pathways, including Lrp5/6 and frizzled receptors. The R-spondins (Rspo) were recently identified as functional ligands for type 2 Lgrs and were shown to synergize with both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling pathways. We determined and report the structure of the Lgr4 ectodomain alone and bound to Rspo1. The structures reveal an extended horseshoe LRR receptor architecture that binds, with its concave side, the ligand furin-like repeats via an intimate interface. The molecular details of ligand/receptor recognition provide insight into receptor activation and could serve as template for stem cell-based regenerative therapeutics development.

Introduction

The Wnt proteins are a family of evolutionarily highly conserved secreted signaling molecules that play crucial roles in many developmental stages, in the self-renewal and maintenance of adult stem cells, as well as in several diseases including cancer (Clevers and Nusse, 2012; Holland et al., 2013; MacDonald et al., 2009). Three Wnt downstream signaling pathways have been characterized, including one canonical Wnt - LRP5/6 - beta-catenin pathway, and two non-canonical pathways: Wnt - planar cell polarity (PCP) and Wnt – Calcium. The canonical Wnt pathway regulates gene transcription, the noncanonical Wnt/PCP pathway regulates the cytoskeleton responsible for the shape of the cell, and the noncanonical Wnt/calcium pathway regulates calcium levels inside the cell. All three Wnt signaling pathways are initiated by Wnt-Frizzled receptor attachment followed by a sequential signal relay through coreceptors and/or downstream protein effectors. The molecular mechanisms that regulate the Wnt signaling pathways are still poorly understood (MacDonald et al., 2009; Nusse and Varmus, 2012).

The R-spondins (Rspo) are members of the thrombospondin type 1 repeat (TSR1) -containing protein superfamily (Kamata et al., 2004). Rspos are capable of synergizing with both canonical and noncanonical PCP Wnt pathways (Kazanskaya et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2006; Nam et al., 2006; Ohkawara et al., 2011), suggesting that they are essential during Wnt-dependent developmental stages and stem cell growth (Blaydon et al., 2006; Jin and Yoon, 2012; Kim et al., 2008; Tomaselli et al., 2008). The four Rspo members share the same domain architecture, containing two N-terminal furin-like (FU) repeats, a TSR1 domain, and a positively charged C-terminal region of various lengths. The frequent occurrence of conserved FU repeats in numerous important growth factors and receptors implies functional significance (Li et al., 2009). The positively charged TSR1 domain and C terminus of Rspos have been predicted to bind glycosaminoglycan (GAG)/proteoglycan and heparin (Nam et al., 2006). Despite their similarity, the four known Rspos serve in different developmental events: Rspo1 regulates sex development; Rspo2 regulates development of limbs, lungs and hair follicles; Rspo3 regulates placenta development; and Rspo4 regulates nail development (de Lau et al., 2012).

The Leucine-rich repeat-containing, G protein coupled receptors (Lgr) are a distinct group of highly conserved proteins. They contain a large ectodomain with multiple leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) involved in ligand binding, connected via a cysteine-rich hinge region to a seven-transmembrane domain responsible for heterotrimeric G protein activation. Phylogenetically, the Lgr family proteins are categorized into three main types (Bella et al., 2008; Hsu et al., 2000; Kajava, 1998). Type 1 includes three hormone receptors, Lgr1, Lgr2 and Lgr3, also known as follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR), luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) and thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR), respectively. Type 3 includes the relaxin hormone receptors Lgr7 and Lgr8 (Kong et al., 2010). The type 2 receptor family, including Lgr4, Lgr5 and Lgr6, is characterized by the presence of an extra large LRR region (16–18 LRRs) within the ectodomain. Type 2 receptors are known to play crucial roles in the embryonic development and are involved in several types of cancer (Barker and Clevers, 2010). They have also drawn significant attention recently because of their roles in adult stem cells, especially after Lgr5 and Lgr6 were identified as specific stem cells marker in multiple adult tissues (Barker et al., 2007; Jaks et al., 2008; Snippert et al., 2010). Rspos were recently identified as the functional ligands of this receptor class (Carmon et al., 2011; de Lau et al., 2011; Glinka et al., 2011; Ruffner et al., 2012), documenting their capability to potentiate Wnt signaling through the three type 2 Lgr proteins. Lgrs4/5/6 were also found to physically associate with Lrp5/6 and frizzled receptors, further highlighting their critical role in Wnt signaling (Binnerts et al., 2007; Carmon et al., 2012; Nam et al., 2006; Schuijers and Clevers, 2012; Wei et al., 2007).

Understanding the structural basis of ligand-receptor binding and ligand-induced receptor/co-receptor activation is vital to understand the mechanism of signal transduction. We, therefore, determined and report here the crystal structures of unliganded Lgr4 and the Lgr4/Rspo1 complex. The structures reveal an extended horseshoe LRR receptor architecture that binds, with its concave side, the ligand furin-like repeats via an intimate interface. The molecular details of ligand/receptor recognition provide insight into receptor activation and could serve as template for future stem cell-based regenerative therapeutics development.

Results and Discussion

The xenopus Lgr4 ectodomain (residues 24–455), and full-length human Rspo1 were expressed in HEK293 cells and crystallized. For an alignment between human and xenopus Lgr4 see Figure S1. The C-terminal hinge region in the ectodomain of type-2 Lgr receptors contains 5 cysteine residues and is predicted to be disordered. The function of this region in the other two Lgr types is to facilitate GPCR activation. Since Rspos-mediated Wnt signal doesn’t involve GPCR activation (Ruffner et al., 2012), and the full ectodomain of Lgr4 protein aggregates in solution, the hinge region was excluded from the construct used for crystallographic analysis.

Structure of Lgr4

The unliganded Lgr4 ectodomain crystals diffracted to 2.6 Å, and a 2.9 Å single wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) data set from a platinum derivative was used for initial phase calculation. The final model is refined to an Rfree of 27% at 2.6 Å resolution (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Lgr4 | Lgr4 | Complex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native | (NH4)2PtCl4 (SAD) | Lgr4/Rspo1 | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 113.8 - 2.66 (2.8 - 2.66) | 49.53 - 2.92 (3.08 - 2.92) | 50 - 3.2 (3.31 - 3.2) |

| Space group | C 2 2 21 | P 4 21 2 | C 2 2 21 |

| Unit cell | 60.29 158.582 227.609 90 90 90 | 152.615 152.615 111.458 90 90 90 | 103.379 160.923 82.216 90 90 90 |

| Total reflections | 202138 | 384476 | 51022 |

| Unique reflections | 31899 | 35527 | 11576 |

| Multiplicity | 6.3 (6.4) | 13.1 (13.7) | 4.4 (4.4) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.76 (99.87) | 99.31 (99.28) | 98.34 (96.29) |

| Mean I/sigma(I) | 12.57 (1.77) | 16.32 (1.83) | 10.00 (1.43) |

| Wilson B-factor | 64.49 | 75.15 | 94.06 |

| R-merge | 0.088 (0.872) | 0.096 (1.364) | 0.087 (0.966) |

| R-work | 0.2375 (0.3584) | 0.2560 (0.3981) | |

| R-free | 0.2732 (0.4375) | 0.2938 (0.4582) | |

| Number of atoms | 6807 | 4041 | |

| macromolecules | 6601 | 4027 | |

| ligands | 28 | 14 | |

| water | 178 | 0 | |

| Protein residues | 851 | 526 | |

| RMS(bonds) | 0.005 | 0.003 | |

| RMS(angles) | 1.18 | 1.00 | |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 97 | 92 | |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Clashscore | 14.14 | 13.15 | |

| Average B-factor | 66.60 | 70.60 | |

| macromolecules | 66.80 | 70.50 | |

| ligands | 75.80 | 93.40 | |

| solvent | 58.90 |

Statistics for the highest-resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

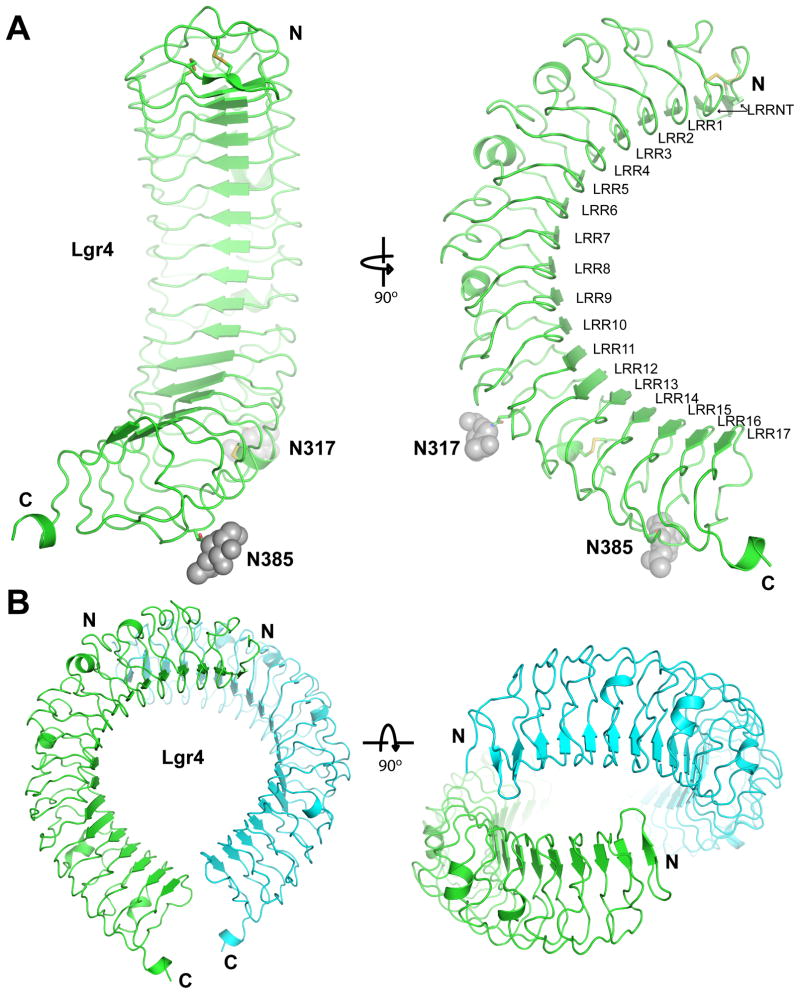

The Lgr4 crystals contain two Lgr4 molecules in each asymmetric unit (r.m.s.d. between Cα positions of 0.4 Å). The Lgr4 structure, which to the best of our knowledge is the first reported structure of an unbound Lgr, reveals a large, horseshoe-shaped molecular architecture consisting of 16 LRRs that adopt a right-handed solenoid (Fig. 1A). The inner and the outer radii of the Lgr4 horseshoe are ~24 Å and 40 Å, respectively. Notably, unlike many other LRR-containing protein structures, the Lgr4 solenoid has a slight (~20 degrees) right-handed twist. The concave inner surface, formed by 16 parallel β strands from the LRR region, and two anti-parallel strands from the N-terminal cap region (LLRNT), assembles into a highly curved, continuous β sheet that spans 180° of arc. The convex outer surface contains more diverse secondary structure elements, including loops of various lengths, α helices, and β strands. The Lgr4 solenoid is further stabilized by three disulfide bonds, two (C32-C38 and C36-C46) located in the N-terminal cap region, and one (C342-C367) located between LRR13 and LRR14. Interestingly one free cysteine residue (C223) is also present.

Figure 1.

Structure of unliganded Lgr4. A. Two orthogonal views of the structure of the unbound Lgr4 ectodomain colored in green. The sugar moieties at the glycosylation sites are drawn as grey spheres. The N and C termini, as well as the individual LRR repeats, are labeled. LRRNT is the N-terminal LRR capping region. B. Two orthogonal views of the Lgr4 dimer (one molecule is colored in green, and the other, in cyan) observed in the crystals. The Lgr4 ectodomain is dimeric in solution as judged by gel filtration and dynamic light scattering.

Among the 16 LRR modules, two (LRR11 and LRR12) do not strictly obey the LxxLxLxxNxL rule (Kobe and Kajava, 2001). Instead, the N residues are replaced by A309 and T332, respectively. As a result, the asparagine ladder breaks in this region, rendering two longer β-strands.

Primary sequence analysis indicates that the Lingo-1 ectodomain is the closest homolog to Lgr4 among all reported LRR-containing structures. Indeed, the N-terminal region of these two structures can be superimposed with an r.m.s.d. between equivalent Cα positions of 1.2 Å over a stretch of 155 residues (Mosyak et al., 2006), while Lgr4 and FSHR/Lgr1 (Fan and Hendrickson, 2005; Jiang et al., 2012) can be superimposed with an r.m.s.d. between equivalent Cα positions of 2.4 Å. over 176 residues. The presence of the unique gradual right-handed twist in the Lgr4 structure (but not in Lingo-1 or FSHR) does not seem to be essential for R-spondin binding (see below), but could be functionally relevant for formation of higher order ligand/receptor/co-receptor assemblies, possibly involving other proteins regulating Wnt signaling.

N-linked glycosylation was observed in all five predicted locations, N71, N202, N297, N317 and N385. The first three were not included in the model due to their weak electron density. None of these glycosylation sites are located at the concave site where they could interfere with ligand binding.

Lgr4 forms a dimier in solution, as judged by gel filtration chromatography and dynamic light scattering (data not shown), and the two Lgr4 copies in the crystal AU bind each other in a tail-to-tail assembly with the N-terminal regions, including the LRRNT and the first four LRRs, interacting side by side (Fig. 1B). Several salt-bridges (including R159-D41 and D41-K111), hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts participate in this assembly, which is also observed in other distinct Lgr4 crystal forms that we obtained (not shown) suggesting functional relevance.

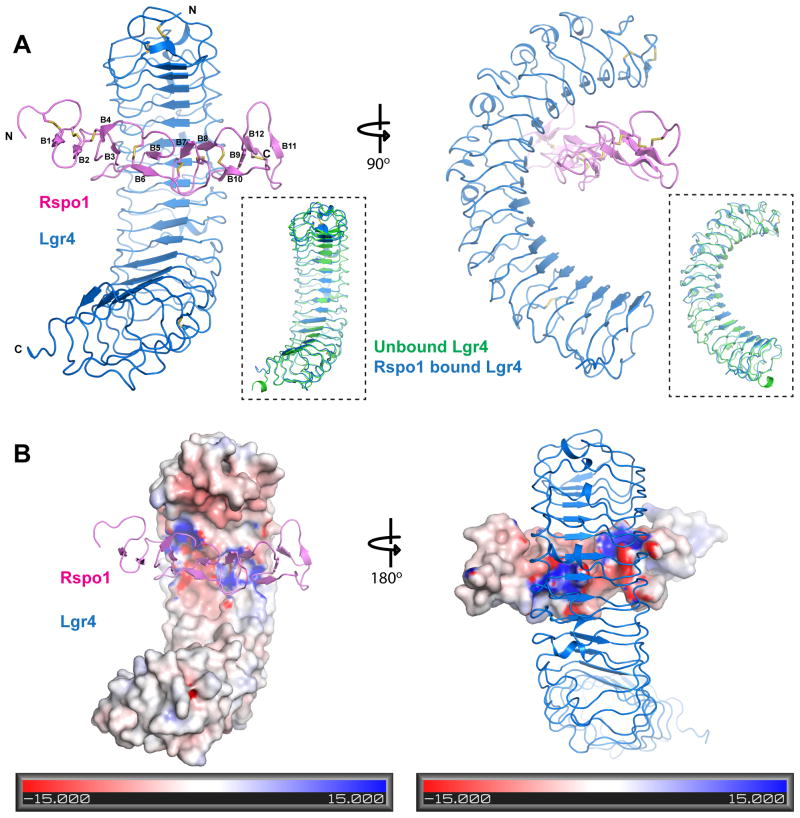

Overall structure of the Lgr/R-spondin complex

Crystals of the complex diffracted to 3.2 Å and the structure was determined by molecular replacement using the structure of unbound Lgr4 (Table 1). As most other known LRR-containing receptors, Lgr4 binds its R-spondin ligand at the concave LRR surface region (Fig. 2A), somewhat closer to its N-terminus. The Lgr4/Rspo1 complex migrates as a 1:1 heterodimer in a gel filtration column and the asymmetric unit of the crystals contains one ligand and one receptor molecules.

Figure 2.

Structure of the Lgr4/R-spondin complex. A. Two orthogonal views of the ligand/receptor complex. Lgr4 is colored in blue and R-spondin, in magenta. The inserts are superimpositions of ligand-bound (blue) and unliganded (green) Lgr4. Secondary structure elements in R-spondin are labeled. B. The Lgr4/R-spondin complex with either Lgr4 (Left Panel) or R-spondin complex (Right Panel) are drawn as solvent accessible surfaces and color-coded by electrostatic surface potential. This panel illustrates the complementary-charged surfaces that constitute the Lgr4/R-spondin interface.

Structure of Rspo1 in the Lgr4/Rspo1 complex

The N-terminal receptor-binding domain of Rspo1, containing the FU repeats, consists of 12 β strands (B1-B12) forming six beta hairpins assembled irregularly side by side. Specificaly each of the two FU repeats consists of three hairpins, the folding of which resembles interconnected paper clips. The beta hairpins are further stabilized by 8 disulfide bonds (C40-C47, C44-C53, C56-C75, C79-C94, C97-C105, C102-C111, C114-C125, C129-C142). The R-spondin construct used for crystallization also included the adjacent thrombospondinn-1 type repeat (TSR1) and the C-terminal basic residue cluster, but these regions were not well ordered in the electron-density map and were not included in the model.

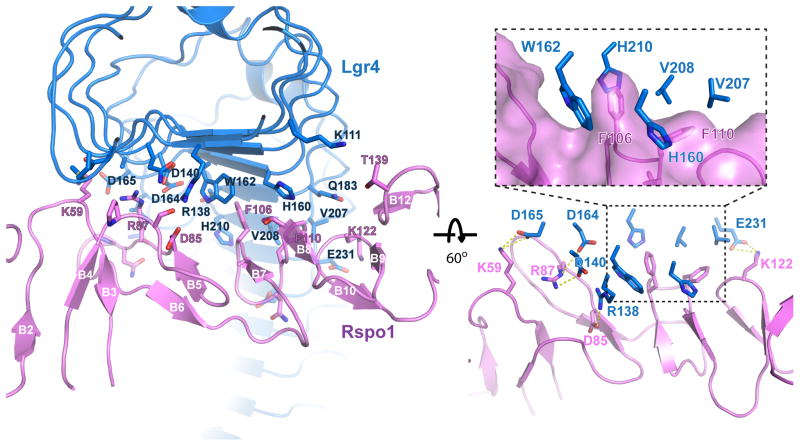

Lgr4/Rspo1 complex interface

The Lgr4/Rspo1 interface involves repeats LRR1 and LRR3-LRR9 in Lgr4 which bind to residues in five of the six hairpins in the two FU repeat. It buries approximately 1860 Å2 of surface area, which is smaller, for example, than the FSHR/FSH interface (2600 Å2) (Fan and Hendrickson, 2005). The interface (Fig. 3) is composed of mostly polar contacts that surround a hydrophobic patch in the middle. The polar interactions include salt-bridges (between K59Rspo1 and D165Lgr4; R87Rspo1 and D140Lgr4; R87Rspo1 and D164Lgr4; K122 Rspo1 and E231Lgr4; D85Rspo1 and R138Lgr4) and several hydrogen bonds (including between K59 Rspo1 and N117 Lgr4; T112 Rspo1 and H160 Lgr4; N109 Rspo1 and E255 Lgr4). The hydrophobic patch displays an interesting “clamping” binding mode. Specifically, F74 of Rspo1 is clamped by four Lgr4 hydrophobic residues (H160, W162, V208 and H210) that fully surround it (Fig. 3, insert). This hydrophobic clamp is further enhanced by two adjacent hydrophobic residues, F78 in Rspo1 and V207 in Lgr4. These seven residues composing the hydrophobic patch are strictly conserved in all four Rspo members and Lgr4, Lgr5 and Lgr6 across species, indicating the importance of this interaction.

Figure 3.

The Lgr4/R-spondin interface. Two orthogonal views of the binding interface between Lgr4 (colored in blue) and R-spondin (colored in magenta). Interacting residues are drawn as stick figures and labeled. Secondary structure elements in R-spondin are also labeled. The insert in the right panel is a zoom-in of the hydrophobic “clamp” region of the Lgr4/R-spondin interface, with the R-spondin solvent accessible surface drawn in magenta.

Electrostatic R-spondin1/Lgr4 interactions

Lgr4 contains a highly charged patch in the ligand binding region. The receptor binding region of Rspo1, is also highly charged (Fig. 2B). The complementary-shaped surfaces and the complementary charges result in the formation of the highly intimate interface, which includes many salt bridges. The structure, thus, indicates that the stability of this interface is dependent on pH and ion strength, suggesting that the binding might be regulated by the environmental conditions during signaling, for example pH change upon endocytosis. The adjacent TSR1 and C-terminal regions in Lgr4 are highly positively charged, which could facilitate interactions with negatively charged proteins and/or GAG/proteoglycans.

Comparison of ligand bound and free Lgr4

Ligand binding does not induce significant conformational changes in Lgr4. Indeed the two structures can be superimposed with an r.m.s.d between Cα positions of approximately 0.7Å (Fig. 2, inserts). Interestingly, though, ligand binding causes disruption of the Lgr4 dimers both in solution and in the crystals. The biological significance of this is yet unclear. In addition, crystal-packing interactions result in the formation of a 2:2 Lgr4/Rspo1 heterotetramers (Fig. S2), which are very similar in architecture to the 2:2 heterotetramers observed in the Toll-like receptor TLR4-MD2 structure (Kim et al., 2007; Ohto et al., 2012; Park et al., 2009). Specifically, two Lgr4 molecules bind each other side by side with the Lgr4 concave regions facing opposite directions. Each Rspo1 molecule contacts both Lgr4 molecules in the 2:2 complex: in addition to the primary binding interface described above, the Rspo1 N-terminus interacts with the other Lgr4 molecule to stabilize the 2:2 complex, burying a total surface area of ~4248 Å2 in the process.

Implications for receptor activation

The fact that ligand binding does not significantly alter the conformation of Lgr4 excludes the possibility of a simple mechanical signal-relaying mechanism. Instead, changes in the Lgr4 receptor oligomerization state and/or orientation on the cell surface might be important for signal transduction. In the case of the TLR4-MD2 complex, it was proposed that the 2:2 assembly brings the C-terminal regions of two TLR ectodomains into juxtaposition in order to facilitate signaling initiation inside the cell mediated by their intracellular TIR domains (Kim et al., 2007; Ohto et al., 2012; Park et al., 2009). However, Rspo/Lgr binding does not activate the heterotetrameric G proteins and an architecturally similar 2:2 Lgr4/Rspo1 complex could serve a different purpose. A possible mechanism could be that Rspo1 binding results in alterations in the architecture of the Lgr4 receptor assemblies on the cell surface, which affect their physical association with co-receptors, such as Lrp and Frizzled, triggering the activation of the latter. Rspo1 binding could also facilitate recruitment of other signaling components to the Lgr4/Lrp/Frizzled complexes via interactions involving the TSR1 or C-terminal domains.

Implication for drug design

The Lgr4-Rspo interactions can be an important drug target because they regulate, via direct association with Wnt receptors, stem cell development and cancer progression. Our structures suggest that the relatively small Lgr/Rspo binding interface can be targeted by small molecule inhibitors to alter the downstream signaling outcomes. Indeed the clamp type binding module can be mimicked in organic molecules using structure-based design. Thus the reported here data provide a template that could facilitate the development of novel stem cell based regenerative therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

A xenopus Lgr4 (GeneID:100144922) construct (residue 24–455), and full-length human Rspo1 (GeneID:284654) were cloned into a modified pcDNA3.1+ vector (Invitrogen) and expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells for crystallization. The purification of the secreted recombinant proteins via ProteinA affinity chromatography was facilitated by addition of C-terminal Fc-tags. The complex was prepared by mixing Lgr4 and Rspo1 in 1:1.5 molar ratio and purified by size-exclusion chromatography (GE Biosciences). The fractions were analyzed in SDS-PAGE. Purified Lgr4 and Lgr4/Rspo1 complex were both concentrated to 10 mg/ml in HBS buffer (20mM Hepes pH7.2, 150mM NaCl).

Crystallization and structure determination

The initial crystallization conditions were identified using crystal screen Index and PEG/ION kits (Hampton Research) using robot screening (TTP LabTech’s Mosquito). After several rounds of optimization using hanging drop vapor diffusion at room temperature, crystals of both Lgr4 alone and in complex with Rspo1 grew to optimal size. The unliganded LRR ectodomain region was crystallized against a reservoir containing 22% PEG3350, 200 mM MgCl2 and 100 mM BisTris pH 5.7. The Lgr4/Rspo1 complex was crystallized against a reservoir containing 17% PEG3350, 30 mM Citric Acid, 100 mM BisTris-Propane pH 7.6. Crystals were frozen in liquid Nitrogen with 20% glycerol as cryo-protectant. Diffraction data were collected at beamline NE-CAT ID-24 of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. Data images were processed using HKL2000 (Minor, 1997). A 2.9 Å single wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) Lgr4 crystal data set from a platinum (NH4)2PtCl4 derivative was used for the initial phase calculation in PHENIX. The initial phase map was clear enough for Lgr4 model building in the program Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004). The model was then refined using a higher resolution dataset. The complex structure was determined by Molecular Replacement with the program Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007) using the Lgr4 structure as a search model. The map of the receptor binding region of Rspo1 was clear enough for initial model building. The model was then built and refined iteratively using Coot and PHENIX Refine in the program suite PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010). The crystallographic analysis statistics are presented in Table 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Momchil Kolev for technical support and Dr. Yehuda Goldgur for help with data collection. X-ray diffraction studies were conducted at the Advanced Photon Source on the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines, which are supported by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (5P41RR015301-10) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (8 P41 GM103403-10) from the National Institutes of Health. Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

Accession Numbers

The Protein Data Bank accession numbers for the Lgr4 and Lgr4/Rspo1 structures are 4LI1 and 4LI2, respectively.

Note added in proof.

While this manuscript was being submitted and revised, three advanced online publications announced similar structures: Wang D. et al., Genes Dev., 27(12):1339-1344; Chen PH et al., Genes Dev., 27(12):1345-1350; Peng WC, Cell Reports, 3: 1885-1892.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, Clevers H. Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptors as markers of adult stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1681–1696. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bella J, Hindle KL, McEwan PA, Lovell SC. The leucine-rich repeat structure. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2008;65:2307–2333. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8019-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binnerts ME, Kim KA, Bright JM, Patel SM, Tran K, Zhou M, Leung JM, Liu Y, Lomas WE, 3rd, Dixon M, et al. R-Spondin1 regulates Wnt signaling by inhibiting internalization of LRP6. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:14700–14705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702305104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaydon DC, Ishii Y, O’Toole EA, Unsworth HC, Teh MT, Ruschendorf F, Sinclair C, Hopsu-Havu VK, Tidman N, Moss C, et al. The gene encoding R-spondin 4 (RSPO4), a secreted protein implicated in Wnt signaling, is mutated in inherited anonychia. Nature genetics. 2006;38:1245–1247. doi: 10.1038/ng1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmon KS, Gong X, Lin Q, Thomas A, Liu Q. R-spondins function as ligands of the orphan receptors LGR4 and LGR5 to regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:11452–11457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106083108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmon KS, Lin Q, Gong X, Thomas A, Liu Q. LGR5 interacts and cointernalizes with Wnt receptors to modulate Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Molecular and cellular biology. 2012;32:2054–2064. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00272-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lau W, Barker N, Low TY, Koo BK, Li VS, Teunissen H, Kujala P, Haegebarth A, Peters PJ, van de Wetering M, et al. Lgr5 homologues associate with Wnt receptors and mediate R-spondin signalling. Nature. 2011;476:293–297. doi: 10.1038/nature10337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lau WB, Snel B, Clevers HC. The R-spondin protein family. Genome biology. 2012;13:242. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-3-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan QR, Hendrickson WA. Structure of human follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with its receptor. Nature. 2005;433:269–277. doi: 10.1038/nature03206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinka A, Dolde C, Kirsch N, Huang YL, Kazanskaya O, Ingelfinger D, Boutros M, Cruciat CM, Niehrs C. LGR4 and LGR5 are R-spondin receptors mediating Wnt/beta-catenin and Wnt/PCP signalling. EMBO reports. 2011;12:1055–1061. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JD, Klaus A, Garratt AN, Birchmeier W. Wnt signaling in stem and cancer stem cells. Current opinion in cell biology. 2013;25:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SY, Kudo M, Chen T, Nakabayashi K, Bhalla A, van der Spek PJ, van Duin M, Hsueh AJ. The three subfamilies of leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptors (LGR): identification of LGR6 and LGR7 and the signaling mechanism for LGR7. Molecular endocrinology. 2000;14:1257–1271. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.8.0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaks V, Barker N, Kasper M, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, Clevers H, Toftgard R. Lgr5 marks cycling, yet long-lived, hair follicle stem cells. Nature genetics. 2008;40:1291–1299. doi: 10.1038/ng.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Liu H, Chen X, Chen PH, Fischer D, Sriraman V, Yu HN, Arkinstall S, He X. Structure of follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with the entire ectodomain of its receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:12491–12496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206643109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin YR, Yoon JK. The R-spondin family of proteins: emerging regulators of WNT signaling. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2012;44:2278–2287. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajava AV. Structural diversity of leucine-rich repeat proteins. Journal of molecular biology. 1998;277:519–527. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamata T, Katsube K, Michikawa M, Yamada M, Takada S, Mizusawa H. R-spondin, a novel gene with thrombospondin type 1 domain, was expressed in the dorsal neural tube and affected in Wnts mutants. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2004;1676:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazanskaya O, Glinka A, del Barco Barrantes I, Stannek P, Niehrs C, Wu W. R-Spondin2 is a secreted activator of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and is required for Xenopus myogenesis. Developmental cell. 2004;7:525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HM, Park BS, Kim JI, Kim SE, Lee J, Oh SC, Enkhbayar P, Matsushima N, Lee H, Yoo OJ, Lee JO. Crystal structure of the TLR4-MD-2 complex with bound endotoxin antagonist Eritoran. Cell. 2007;130:906–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KA, Wagle M, Tran K, Zhan X, Dixon MA, Liu S, Gros D, Korver W, Yonkovich S, Tomasevic N, et al. R-Spondin family members regulate the Wnt pathway by a common mechanism. Molecular biology of the cell. 2008;19:2588–2596. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KA, Zhao J, Andarmani S, Kakitani M, Oshima T, Binnerts ME, Abo A, Tomizuka K, Funk WD. R-Spondin proteins: a novel link to beta-catenin activation. Cell cycle. 2006;5:23–26. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.1.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe B, Kajava AV. The leucine-rich repeat as a protein recognition motif. Current opinion in structural biology. 2001;11:725–732. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(01)00266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong RC, Shilling PJ, Lobb DK, Gooley PR, Bathgate RA. Membrane receptors: structure and function of the relaxin family peptide receptors. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2010;320:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SJ, Yen TY, Endo Y, Klauzinska M, Baljinnyam B, Macher B, Callahan R, Rubin JS. Loss-of-function point mutations and two-furin domain derivatives provide insights about R-spondin2 structure and function. Cellular signalling. 2009;21:916–925. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Developmental cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. Journal of applied crystallography. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minor ZOaW. Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosyak L, Wood A, Dwyer B, Buddha M, Johnson M, Aulabaugh A, Zhong X, Presman E, Benard S, Kelleher K, et al. The structure of the Lingo-1 ectodomain, a module implicated in central nervous system repair inhibition. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:36378–36390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam JS, Turcotte TJ, Smith PF, Choi S, Yoon JK. Mouse cristin/R-spondin family proteins are novel ligands for the Frizzled 8 and LRP6 receptors and activate beta-catenin-dependent gene expression. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:13247–13257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R, Varmus H. Three decades of Wnts: a personal perspective on how a scientific field developed. The EMBO journal. 2012;31:2670–2684. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawara B, Glinka A, Niehrs C. Rspo3 binds syndecan 4 and induces Wnt/PCP signaling via clathrin-mediated endocytosis to promote morphogenesis. Developmental cell. 2011;20:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohto U, Fukase K, Miyake K, Shimizu T. Structural basis of species-specific endotoxin sensing by innate immune receptor TLR4/MD-2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:7421–7426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201193109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BS, Song DH, Kim HM, Choi BS, Lee H, Lee JO. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex. Nature. 2009;458:1191–1195. doi: 10.1038/nature07830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffner H, Sprunger J, Charlat O, Leighton-Davies J, Grosshans B, Salathe A, Zietzling S, Beck V, Therier M, Isken A, et al. R-Spondin potentiates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling through orphan receptors LGR4 and LGR5. PloS one. 2012;7:e40976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuijers J, Clevers H. Adult mammalian stem cells: the role of Wnt, Lgr5 and R-spondins. The EMBO journal. 2012;31:2685–2696. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert HJ, Haegebarth A, Kasper M, Jaks V, van Es JH, Barker N, van de Wetering M, van den Born M, Begthel H, Vries RG, et al. Lgr6 marks stem cells in the hair follicle that generate all cell lineages of the skin. Science. 2010;327:1385–1389. doi: 10.1126/science.1184733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli S, Megiorni F, De Bernardo C, Felici A, Marrocco G, Maggiulli G, Grammatico B, Remotti D, Saccucci P, Valentini F, et al. Syndromic true hermaphroditism due to an R-spondin1 (RSPO1) homozygous mutation. Human mutation. 2008;29:220–226. doi: 10.1002/humu.20665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Q, Yokota C, Semenov MV, Doble B, Woodgett J, He X. R-spondin1 is a high affinity ligand for LRP6 and induces LRP6 phosphorylation and beta-catenin signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:15903–15911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.