Abstract

Patients with pancreatic cancer, which is characterized by an extensive collagen-rich fibrotic reaction, often present with metastases. A critical step in cancer metastasis is epithelial to mesenchymal transition, which can be orchestrated by Snail family of transcription factors. To understand the role of Snail (Snai1) in pancreatic cancer, we generated transgenic mice expressing Snail in the pancreas. While there was robust Snail expression, no phenotypic changes were observed. Since chronic pancreatitis can contribute to pancreatic cancer development, Snail-expressing mice were treated with cerulein to induce pancreatitis. Although there was significant tissue injury, no difference in pancreatitis was observed between control and Snail-expressing mice. As Kras mutation is necessary for tumor development in mouse models of pancreatic cancer, we generated mice expressing both mutant KrasG12D and Snail (Kras+/Snail+). Compared to control mice (Kras+/Snail−), Kras+/Snail+ mice developed acinar ectasia and more advanced acinar to ductal metaplasia. The Kras+/Snail+ mice exhibited increased fibrosis, increased pSmad2 levels and TGF-β2 expression, and activation of pancreatic stellate cells. To further understand how Snail promoted fibrosis, we established an in vitro model to examine the effect of Snail expression in pancreatic cancer cells on stellate cell collagen production. Snail expression in pancreatic cancer cells increased TGF-β2 levels and conditioned media from Snail-expressing pancreatic cancer cells increased collagen production by stellate cells. Additionally, inhibiting TGF-β signaling in stellate cells attenuated the conditioned media-induced collagen production by stellate cells. Together these results suggest that Snail contributes to pancreatic tumor development by promoting fibrotic reaction through increased TGF-β signaling.

Keywords: Snail, Fibrosis, Pancreatic Cancer, Stellate Cells, TGF-β

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is characterized by a pronounced fibrotic reaction consisting of proliferating stromal cells together with collagen-rich extracellular matrix (1–3). This fibrotic reaction, which can account for over 80 percent of the tumor mass (1, 2), has been shown to limit the delivery of therapeutics, and contribute to cell survival and drug resistance (4–6). A number of studies have identified activated pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) as the major mediator of the fibrotic tumor environment (7–9). Upon activation, the PSCs differentiate into activated myofibroblasts, and begin expressing α-smooth muscle actin and depositing excess type I collagen (7). Activation of PSCs is dependent on growth factors, such as TGF-β, secreted by pancreatic cancer cells (7, 10). In human PDAC tumor tissue, especially in the areas of fibrosis, there is elevated TGF-β signaling (11–13).

Metastatic dissemination to regional lymph nodes and liver is a common feature of pancreatic cancer (14, 15). Epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a key step in tumor metastasis, conferring an invasive phenotype onto tumor cells (16–18). An important regulator of EMT is the Snail (Snai1) transcription factor, which is overexpressed in pancreatic cancer with increasing tumor grade (19). Snail expression in PDAC tumors significantly correlates with lymph node and distant metastases (20). Snail also promotes fibrosis in vivo (21, 22). Transgenic overexpression of Snail in the kidney is sufficient to induce fibrosis in mice (21), while ablation of Snail in the liver attenuates chemical-induced fibrosis (22). Despite the importance of Snail in cancer progression and its association with fibrosis, the contribution of Snail to pancreatic cancer development remains to be defined.

In this report we examined the role of Snail in pancreatic tumor development by generating transgenic mice with targeted expression of human Snail to elastase (EL) positive cells in the pancreas. Compared to littermate Snail- control mice, expression of Snail in the pancreatic acinar cells had no effect on tissue morphology or on response to pancreatic injury induced by cerulein-induced pancreatitis. However, when the mice were crossed with EL-KrasG12D mice, Snail in the context of mutant Kras promoted advanced acinar to ductal metaplasia and proliferation. Snail expression in the KrasG12D mice also enhanced fibrosis, TGF-β signaling (increased pSmad2 levels and TGF-β2 expression) and activation of PSCs. To define a potential mechanism for the increased fibrosis, we established an in vitro model to examine the effect of overexpressing Snail in pancreatic cancer cells on stellate cell collagen deposition. We demonstrate that Snail expression in pancreatic cancer cells increased TGF-β2 levels and the conditioned media from Snail-expressing pancreatic cells increased TGF-β signaling in stellate cells to drive stellate cell collagen production. These results increase our understanding of the role of the EMT regulator Snail in pancreatic cancer progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals/Reagents

Snail (clone C15D3) and pSmad2(Ser465/467; 3101) antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA), E-cadherin antibody (13-1700) was from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY), type I collagen antibody (1310-01) was from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, AL), and α-tubulin (sc-8035) and TGF-β receptor type I (TβRI, sc-398) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Secondary antibodies were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), the TβRI inhibitor SB431542 was from Tocris (Ellisville, MO), and the nucleofector electroporation kit was purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD).

Transgenic Mice

All animal work was conducted in compliance with the Northwestern University IACUC guidelines. TRE-Snail transgenic mice, in which Snail expression is under the control of seven tet-responsive elements (TREs) upstream of a minimal CMV promoter (23, 24), were created by the Transgenic Core Facility at Northwestern University. The TRE-Snail mice were crossed with EL-tTA mice, kindly provided by Dr. Eric Sandgren (23), to generate EL-tTA/TRE-Snail bigenic mice. In EL-tTa mice, the transactivator tTa is expressed downstream of elastase (EL) promoter, thus enabling targeting of Snail to pancreatic acinar and centroacinar cells (23, 24). The bigenic mice were further crossed with EL-KrasG12D mice, which express constitutively active mutant Kras in the pancreatic acinar cells (12, 23, 24). The trigenic mice were raised in the same cage as their littermates, and all comparisons were made between littermates with the same genetic background.

Histologic analysis

Using a 1 cm × 1 cm reticle, lesion count was determined by counting all cystic lesions greater than 100 μm in maximum diameter (12). The extent of acinar to ductal metaplasia (ADM), defined by vacuolization of the normal acini with formation of abnormal ducts along with evidence of dysplasia and fibrosis, was assessed at 40x magnification and a score of less than 25% (1+), 25%–75% (2+), or greater than 75% (3+) of the pancreas containing ADM was assigned to each mouse (12). The samples were trichrome stained and whole gland fibrosis was scored according to the percentage of the entire gland containing pathologic fibrosis: less than 25% (1+), 25–50% (2+) or greater than 50% (3+) (12). All histologic comparisons were made between littermates raised in the same cage, all with the same genetic background.

Immunofluorescence

Pancreatic tissue specimens from paired littermate Kras+/Snail− and Kras+/Snail+ were stained for pSmad2 (Cell Signaling), α-SMA (ab-5694, Abcam), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA; sc-56, Santa Cruz), Snail (T-18, Santa Cruz), and CK-19 (TROMA-III, University of Iowa). Antigen retrieval for pSmad2, α-SMA, PCNA, Snail, and CK-19 was performed as previously described (11, 12, 25). Photographs for quantitative comparison were taken using a Carl Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope and camera.

Cell culture

AsPC1 and Panc1 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) (26, 27), while human stellate cells have been described previously (12, 28). AsPC1 and Panc1 cells were tested by STR profiling at the Johns Hopkins Genetic Resources Core Facility. Stellate cells were verified by R.F. Hwang.

Conditioned Media

AsPC1 and Panc1 cells expressing Snail were generated as detailed previously (26, 27). Cells expressing control vector or Snail were allowed to condition the media for 72 hours to generate Vector- and Snail-conditioned media (VCM and SnCM respectively).

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting for type I collagen, Snail, TβRI and α-tubulin was done as previously described (11, 12, 27).

Quantitative Real Time-PCR analysis

Reverse transcription of mRNA to cDNA was performed using Taqman Reverse Transcription reagents from Applied Biosystems (11, 29). Quantitative gene expression was performed with gene specific Taqman probes, TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix and the 7500 Fast Real-time PCR System from Applied Biosystems. The data were then quantified with the comparative CT method for relative gene expression (11).

Stellate cell collagen expression

Vector- and Snail-conditioned media were added for 48–72 hours to stellate cells grown on tissue culture plastic, which were then processed for either mRNA or total protein as previously published (11, 29, 30). Relative collagen production in stellate cells treated with Snail-conditioned media was normalized to levels present in stellate cells treated with Vector-conditioned media using the Comparative CT method and GAPDH as normalization control (11, 12).

For TβRI inhibition experiments with siRNA, stellate cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA against TβRI (Ambion) using a nucleofector kit (12, 27). The cells were allowed to recover for 24 hours and were then grown in conditioned media for an additional 48 hours before being assayed for collagen mRNA expression. The TβRI kinase activity in the stellate cells was also blocked using SB431542.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons of in vivo data were made using Chi-square analysis or Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (12). In vitro results were compared using paired t-test analysis. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. All analyses were performed on GraphPad Prism 5 for Mac OS X.

RESULTS

Snail expression alone in the mouse pancreas does not cause any phenotypic changes

Recent evidence demonstrates the importance of EMT in promoting metastatic dissemination (17, 31, 32). Previous studies have shown that the EMT regulator Snail is upregulated in pancreatic cancer and its expression correlates with lymph node and distant metastases (19, 20). To understand the role of Snail in pancreatic cancer progression TRE-Snail transgenic mice, where human Snail expression is driven by seven tetracycline response elements (TREs) upstream of a minimal cytomegalovirus promoter, were generated (Fig. 1A). The TRE-Snail mice were crossed with EL-tTA mice, which allows targeting of Snail to the acinar and centroacinar cells in the pancreas (12, 23), to generate EL-tTA+/TRE-Snail+ bigenic mice (Fig. 1A). These mice were designated Snail+ mice while control mice that did not express Snail were designated Snail− mice. As shown by RT-PCR analyses of pancreatic tissue, Snail was expressed in Snail+ mice (Fig. 1A, bottom). Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that Snail was localized to the nuclei of pancreatic cells (Fig. 1B). Real time PCR analysis of pancreatic tissue demonstrated that there was ~50% reduction in mouse E-cadherin mRNA expression (Fig. 1C, top). However, the effect on E-cadherin protein levels was minimal despite robust human Snail protein expression (Fig. 1C, bottom). Moreover, E-cadherin expression at cell-cell junctions was largely preserved in cells expressing Snail (Supplemental Fig. 1). Furthermore, H&E examination of the Snail-expressing pancreatic tissue revealed no abnormalities in the tissue architecture (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. Snail expression alone in the mouse pancreas does not cause any phenotypic changes.

A. The TRE-Snail mice were generated as detailed in the Materials and Methods and crossed with EL-tTA mice to generate Snail− (EL-tTA+/TRE-Snail− or EL-tTA-/TRE-Snail−) and Snail+ (EL-tTA+/TRE-Snail+) mice. The mRNA samples from pancreas of control Snail− mice and Snail+ mice were analyzed for human (h) Snail, and mouse (m) GAPDH by RT-PCR (bottom). B. Pancreas from Snail− and Snail+ mice were examined for Snail expression by immunofluorescence using DAPI to counterstain the nuclei. C. The mRNA samples from pancreas of control Snail− and Snail+ mice were analyzed for mE-cadherin and mGAPDH by real time PCR (top). *, p<0.05. Tissue lysates from Snail− and Snail+ mice were analyzed for E-cadherin, hSnail and α-tubulin by Western blotting (bottom). E-cadherin and α-tubulin protein expression was quantified by densitometry and normalized to the relative expression in Snail− mice. D. Sections of mouse pancreas from Snail− and Snail+ mice were H&E stained and observed at low (left) and high (right) magnification by phase microscopy.

Snail expression in the mouse pancreas does not modulate pancreatitis-induced injury

Since chronic pancreatitis can contribute to pancreatic cancer development and progression (32, 33), we examined the effect of expressing Snail in a chronic pancreatitis model (Fig. 2A, left). Initially, we examined the effect of chronic pancreatitis on Snail expression in wild-type mice by administering cerulein, a cholecystokinin (CCK) analog that causes premature release of digestive enzymes and subsequent pancreatic damage (34). There was no significant difference in Snail expression between control mice treated with PBS and mice treated with cerulein (p=0.70, Fig. 2A, right). We next examined whether Snail expression in vivo modulated the extent of tissue damage following cerulein treatment. Snail− and Snail+ mice were treated with cerulein and the pancreata were collected 3, 10 and 17 days following cessation of cerulein administration. Histological analysis revealed that Snail did not modulate tissue damage following cerulein treatment nor affected the resolution of pancreatitis in our model system (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Snail expression in the mouse pancreas does not modulate pancreatitis-induced injury.

A. Cerulein (100 μg/kg) or phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was i.p. injected 5 days per week for 3 weeks (left). Pancreatic tissue was then collected at 3 days after cessation of injections and analyzed for mouse (m) Snail and mGAPDH mRNA expression by real time PCR (right). B. Snail− and Snail+ mice were generated as detailed in Fig. 1 and i.p. injected with cerulein 5 days per week for 3 weeks. Pancreatic tissue from Snail− and Snail+ mice was collected at 3, 10 and 17 days after cessation of cerulein treatment and analyzed by H&E staining.

Snail expression in KrasG12D mice increases acinar to ductal metaplasia (ADM) and proliferation

Expression of mutant Kras (KrasG12D) in acinar cells of EL-KrasG12D mice was previously shown to cause acinar ductal metaplasia (ADM) (12, 23). Thus, we examined the effect of mutant Kras on Snail levels in vivo using EL-KrasG12D mice. The pancreata from EL-KrasG12D mice and control littermates were analyzed for mSnail and mGAPDH mRNA expression by real time PCR. As shown in Fig. 3A, there was a statistically significant increase in mSnail mRNA in EL-KrasG12D mice compared to control littermates. To further understand the role of Snail in vivo, we generated mice expressing both KrasG12D and Snail in the pancreas (Fig. 3B). The bigenic EL-tTA+/TRE-Snail+ were crossed with EL-KrasG12D mice to obtain trigenic EL-KrasG12D/El-tTA+/TRE-Snail+ (Kras+/Snail+) study mice. EL-KrasG12D/EL-tTA+/TRE-Snail−, EL-KrasG12D/EL-tTA-/TRE-Snail+ or EL-KrasG12D/EL-tTA-/TRE-Snail− were used as control (Kras+/Snail−) mice. Only mice that were positively genotyped for both EL-tTA and TRE-Snail expressed human Snail in the pancreas. The experimental mice were aged for 3 months and pancreata collected for analysis. Compared with Kras+/Snail− control mice, the littermate Kras+/Snail+ mice showed increased Snail expression as assessed by RT-PCR and immunofluorescence (Fig. 3B). Similar to our findings in the EL-tTA+/TRE-Snail+ bigenic mice (Fig. 1), Snail had minimal effect on E-cadherin protein levels (Fig. 3B). However, histologic examination showed that Snail disrupted the typical polarized and polygonal architecture of acinar cells (Fig. 3C). The Kras+/Snail+ mice also developed increased ADM as evidenced by loss of eosinophilic granules, vacuolization of acini, development of ductular structures and increase in the surrounding stroma (Fig. 3D). There was also increased staining for cytokeratin-19 (CK-19) in Kras+/Snail+ mice, providing further evidence for increased ADM in these mice (Fig. 3E). Although very few apoptotic cells were observed in either control or study mice (data not shown), immunofluorescence staining for PCNA positive cells showed that Kras+/Snail+ mice exhibited statistically significant increase in proliferation relative to Kras+/Snail− mice (p=0.014, Fig. 3E).

Figure 3. Snail expression in KrasG12D mice increases acinar to ductal metaplasia (ADM) and proliferation.

A. Pancreas from EL-KrasG12D mice (Kras+) and control littermates (Kras-) were analyzed for mSnail and mGAPDH expression by real time PCR. B. The EL-tTA+/Snail+ (Snail+) mice were crossed with EL-KrasG12D mice to generate mice expressing both Snail and KrasG12D in the pancreas (EL-Kras+/EL-tTA+/TRE-Snail+ = Kras+/Snail+) or littermate control mice that expressed only KrasG12D and not Snail (EL-Kras+/EL-tTA+/TRE-Snail− or EL-Kras+/EL-tTA-/TRE-Snail− = Kras+/Snail−). The mRNA samples from pancreas of control Kras+/Snail− mice and Kras+/Snail+ mice were analyzed for human (h) Snail and mouse (m) GAPDH by RT-PCR. Pancreas from Kras+/Snail− and Kras+/Snail+ mice were analyzed for Snail and E-cadherin expression by immunofluorescence using DAPI to counterstain nuclei. C, D. H&E staining of sections of pancreas from littermates at 3 months of age demonstrating morphology (C) and the degree of ADM (D, top). Scale bar corresponds to 100 μm. The extent of ADM was quantified as described in the Materials and Methods. Number of Kras+/Snail− and Kras+/Snail+ mice with less than 25% (1+), 25%–75% (2+), or greater than 75% (3+) of their pancreas containing ADM was determined (n=28 Kras+/Snail− mice, n=41 Kras+/Snail+ mice, p<0.005) (D, bottom). E. Effect of Snail on CK-19 expression and proliferation (PCNA) was determined by immunofluorescence using DAPI to counterstain the nuclei. Relative PCNA(+) cells in paired Kras+/Snail− and Kras+/Snail+ littermates was quantified (n=7 pairs, p=0.014).

Snail expression in KrasG12D mice causes acinar ectasia and promotes pancreatic fibrosis

A particular marked feature of pancreas from Kras+/Snail+ mice was the presence of degenerative acinar structures (‘acinar ectasia’) (35). These structures lacked fibrotic stroma, exhibited flattening of acinar cells, loss of zymogen granules, thus causing the dilated acini to resemble ductules, and contained luminal secretions (Fig. 4A). The tubular complex phenotype is similar to what was seen in previous studies employing the EL-Kras mice (36). Since expression of KrasG12D in mouse pancreas causes development of cystic lesions (12, 23), we also assessed the effect of Snail on the number of cystic lesions. As shown in Fig. 4B, Snail did not significantly affect the number of cystic lesions present in our mouse model. Interestingly, trichrome staining showed that there was increased fibrosis in the Kras+/Snail+ mice compared to the Kras+/Snail− mice (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Snail expression in KrasG12D mice causes acinar ectasia and promotes pancreatic fibrosis.

Kras+/Snail− and Kras+/Snail+ mice were generated as detailed in the Materials and Methods. A. Representative H&E comparison of pancreas from 3-month old mice showing the effect of Snail on the number of acinar ectasia/degenerative lesions. Scale bar corresponds to 100 μm. Number of degenerative lesions in Kras+/Snail− and Kras+/Snail+ mice was determined by microscopic examination of H&E stains (n=9 mice in each group, p<0.05). B. Representative H&E comparison of pancreas from 3 month old mice showing the effect of Snail on the number of cystic lesions. Scale bar corresponds to 100 μm. Average lesion number in 3-month old Kras+/Snail− and Kras+/Snail+ was determined by microscopic examination of H&E stains (n=10 mice in each group, ns). C. Representative trichrome staining (blue = fibrosis) of pancreas from 3-month old Kras+/Snail− and Kras+/Snail+ mice. Scale bar corresponds to 100 μm. The number of Kras+/Snail− and Kras+/Snail+ mice with less than 25% (1+), 25–50% (2+), or greater than 50% (3+) of the gland containing fibrosis was determined (n=14 Kras+/Snail− mice, 20 Kras+/Snail+ mice, p<0.05).

Snail expression in KrasG12D mice increases pSmad2 levels and TGF-β2 expression

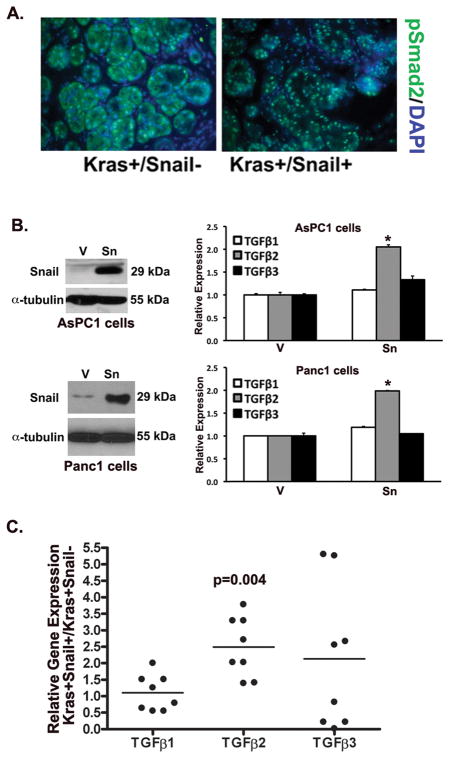

Previously we had shown that fibrotic regions in human pancreatic tumors and fibrotic regions in the EL-KrasG12D mouse model were associated with increased pSmad2 expression (11, 12). Thus we examined whether Snail expression in our KrasG12D mice was also associated with increased pSmad2 expression. As shown in Fig. 5A, there was elevated nuclear pSmad2 staining in the Kras+/Snail+ compared to the littermate control mice (Fig. 4A), indicating that the fibrotic regions of the pancreas in the Kras+/Snail+ mice have elevated TGF-β signaling. To further understand how Snail increased TGF-β signaling, we examined the effect of Snail on TGF-β1, TGF-β2 and TGF-β3 expression. We created pancreatic cancer cells (AsPC1 and Panc1) expressing control vector (V) or Snail (Sn) (26, 27), and the effect on TGF-β expression was determined by real time PCR. As shown in Fig. 5B, Snail expression had no effect on TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 expression; however, Snail increased TGF-β2 mRNA levels by ~2-fold in both AsPC1 and Panc1 cells. Moreover, Snail also increased the levels of TGF-β2 protein in the conditioned media from AsPC1 and Panc1 cells, but had no effect on TGF-β1 or TGF-β3 protein levels (Supplemental Fig. 2). We next examined the effect of Snail expression on TGF-β expression in our mouse samples. As shown in Fig. 5C, Snail expression in the KrasG12D mouse model resulted in a statistically significant increase only in the TGF-β2 mRNA levels.

Figure 5. Snail expression in KrasG12D mice increases pSmad2 levels and TGF-β2 expression.

A. Representative immunofluorescence staining of pSmad2 from 3-month old Kras+/Snail− and Kras+/Snail+ mice using DAPI to counterstain the nuclei. B. Western blot of AsPC1 and Panc1 pancreatic cancer cells expressing control vector (V) or Snail (Sn). The effect of Snail on human TGF-β1, TGF-β2 and TGF-β3 expression was determined by real time PCR and the mRNA levels normalized to the levels present in control vector-expressing cells (*, p<0.05). C. The mRNA samples from pancreas of control Kras+ mice (Kras+/Snail−) and mice expressing both Kras and Snail (Kras+/Snail+) mice were analyzed for mouse (m) TGF-β1, mTGF-β2, mTGF-β3 and mGAPDH by real time PCR and the relative expression normalized to the levels present in control Kras+/Snail− mice. The p-value was calculated using Wilcoxon Signed Rank test.

Snail expression in pancreatic cancer cells promotes collagen production by pancreatic stellate cells through increased TGF-β signaling

As stellate cells are the main contributors to pancreatic fibrosis (7, 28), we determined whether there was increased stellate cell activation in the Kras+/Snail+ tissue. As shown in Fig. 6A, there were more α-SMA positive stromal cells, a marker for activated PSCs (8, 9), in the Kras+/Snail+ tissue compared to control mice. Since our in vivo findings show increased pancreatic fibrosis associated with increased Smad2 phosphorylation and an increase in α-SMA(+) cells, we hypothesized that Snail causes stellate cells to produce more collagen through increased TGF-β signaling. To test this hypothesis, we treated stellate cells with conditioned media from pancreatic cancer cells expressing Snail. Relative to treatment with conditioned media from vector control AsPC1 cells (VCM), treatment with Snail conditioned media (SnCM) increased stellate cell type I collagen mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 6B). We also assessed whether attenuating TGF-β signaling in stellate cells blocked SnCM-induced collagen production. Initially, we used a well-characterized small molecule inhibitor of TβRI kinase activity (SB431542, SB) on SnCM-induced collagen production (12). As shown in Fig. 6C, SB431542 attenuated the effect of SnCM on collagen mRNA expression by stellate cells. We next examined the effect of knocking-down TβRI in stellate cells on collagen production (12). Stellate cells were transfected with control siRNA (Ctrlsi) or TβRI siRNA (TβRIsi), allowed to recover and then treated with VCM and SnCM. As shown in Fig. 6D, TβRI siRNA successfully knocked-down TβRI protein expression and attenuated the effect of SnCM on collagen mRNA expression by stellate cells.

Figure 6. Snail expression in pancreatic cancer cells promotes collagen production by pancreatic stellate cells through increased TGF-β signaling.

A. Representative immunofluorescence staining of α smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) from 3 month old Kras+/Snail− and Kras+/Snail+ mice using DAPI to counterstain the nuclei. B. Conditioned media from AsPC1-V (VCM) and AsPC1-Sn (SnCM) cells were added to human stellate cells grown on tissue culture plastic for 72 hours to examine the effect on collagen production by Western blot and real time PCR analysis (*, p<0.05). C. Stellate cells were grown in AsPC1-conditioned media, treated with either DMSO or TβRI inhibitor SB431542 (10 μM) for 48 hours, and the effect on collagen production was determined by Western blotting and by real time PCR. The mRNA levels were normalized to the levels present in DMSO-treated stellate cells grown in VCM (*, p<0.05). D. Stellate cells were transfected with control siRNA (Ctrlsi) or with TGF-β type I receptor siRNA (TβRIsi), allowed to recover for 24 hours and then treated with AsPC1 conditioned media for an additional 24 hours. Lysates were analyzed for TβRI and α-tubulin expression by Western blotting. The effect on collagen production was determined by Western blotting and by real time PCR and the mRNA levels normalized to the levels present in Ctrlsi-transfected stellate cells treated with VCM (*, p<0.05). The results are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Recent evidence demonstrates the importance of EMT in regulating PDAC progression (31, 32). In this report we show that ectopic expression of Snail, one of the key regulators of EMT in pancreatic cancer (19, 20), in the mouse pancreas was not sufficient to promote histological changes. Although Snail decreased E-cadherin mRNA, and to a lesser extent E-cadherin protein, E-cadherin expression at cell-cell junctions was largely preserved in cells expressing Snail. The apparent preservation of E-cadherin at the cell-cell junctions might be either due to the very modest repression of E-cadherin protein or due to the contribution of E-cadherin from the adjacent non-Snail expressing cells. Consistent with our in vivo findings, Snail expression in mouse skin also demonstrated only a modest repression of E-cadherin protein levels (37). Also, in agreement with the effect of Snail expression in the mouse skin, where Snail had no effect on fibronectin expression (38), Snail expression in the mouse pancreas did not affect fibronectin or vimentin expression (data not shown). Our findings are also consistent with the observation that downregulating Snail in the liver does not cause any phenotypic changes (22). We also found that Snail did not modulate pancreatic injury or recovery following cerulein-induced chronic pancreatitis. This is in contrast to the role of Snail in the liver where hepatic fibrosis following carbon tetrachloride-induced injury required Snail (22). Interestingly, we found that Snail caused phenotypic changes in the context of an oncogenic stimulus. Snail expression in KrasG12D mice caused extensive acinar degeneration/ectasia, advanced ADM, increased proliferation, and increased fibrosis.

ADM is often seen in pancreatic injury and is believed to be a precursor step to oncogenic transformation and tumor initiation. A previous study employing the EL-Kras model used in this study demonstrated there was increased ADM when compared to non-transgenic pancreatic tissue (12, 23). Recently, we showed that expression of the key proteinase membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP, a.k.a. MMP-14) in this EL-Kras mouse model potentiated the extent and severity of ADM in vivo (12). Significantly, Snail increases MT1-MMP not only in pancreatic cancer cells (26, 27), but also in the EL-Kras mouse model (Supplemental Fig. 3). We also observed increased proliferation but no effect on apoptosis in the Kras+/Snail+ tissue. Snail has been shown to promote proliferation in a MIN mouse model of intestinal tumorigenesis (39). Snail also promotes proliferation in a melanoma model by repressing expression of CYLD, a tumor suppressor gene that functions as a deubiquitination enzyme (40).

The degenerative lesions/acinar ectasia present in Snail overexpression in KrasG12D were mostly undifferentiated and lacked fibrotic stroma. Some lesions had prominent tubular complexes with luminal deposits. The tubular complex phenotype is similar to what was seen in previous studies employing the EL-Kras mice (36). In our studies the Kras+/Snail+ invariably had these degenerative lesions. Our observation of Snail promoting degeneration/ectasia in an oncogenic setting is novel and we can only speculate about the mechanism through which this occurs. Interestingly, a recent study highlighted the role of EZH2 in cerulein-induced pancreatic injury and regeneration in KrasG12D mice (41). EZH2 was upregulated following injury and mediated the process of regeneration. Conditional deletion of EZH2 in the pancreas using the p48 promoter prevented the regeneration of acinar cells after injury, supporting its role in the process (41). Since Snail can interact with EZH2 (42, 43), it is possible that Snail may modulate EZH2 function to keep acinar cells in a degenerative state.

Fibrosis is a characteristic feature of pancreatic cancer and has been shown to promote tumor progression and metastasis as well as limit drug delivery and promote drug resistance (1, 4, 5). Snail promoted fibrosis in KrasG12D mice that was associated with increased α-SMA+ cells, suggesting that Snail promotes activation of stellate cells. We also observed increased TGF-β signaling, which is known to mediate the activation of PSCs (44). Interestingly, Snail increased expression of TGF-β2, but not that of TGF-β1 or TGF-β3, in pancreatic cancer cell lines and in the transgenic mouse model. Importantly, TGF-β2 overexpression has been shown to be associated with advanced tumor stage and poor clinical outcome (13). In future studies, we will determine the mechanism by which Snail promotes TGF-β2 expression. Using an in vitro model, we showed that Snail expression in pancreatic cancer cells increased pancreatic stellate cell collagen production through increased TGF-β signaling, indicating cross-talk between cancer cells and stellate cells involving TGF-β to promote fibrosis. As indicated above, Snail expression in pancreatic cancer cells increases MT1-MMP (26, 27), which can contribute to increased TGF-β signaling by cleaving the TGF-β-latency activated protein (45, 46). Importantly, we have previously found that expression of MT1-MMP in the EL-Kras mouse model is also associated with increased TGF-β signaling and fibrosis (12). Snail has also been shown to increase expression of αv-integrins (47), which can promote TGF-β signaling by causing dissociation of the TGF-β-latency activated protein from TGF-β (48–52). In future studies, we will also determine whether targeting TGF-β signaling in the Kras+/Snail+ mice attenuates fibrosis.

Overall, we demonstrate that Snail alone does not promote morphological changes in the pancreas or modulate pancreatitis-induced injury and response. However, in the setting of oncogenic KrasG12D Snail promotes increased ADM, proliferation, acinar degeneration and fibrosis. Mechanistically, Snail increases TGF-β signaling within the microenvironment, activating pancreatic stellate cells and inducing production of more type I collagen. These results increase our understanding of the interplay between the EMT regulator Snail and fibrosis in pancreatic cancer progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

GRANT SUPPORT

This research was supported by grant R01CA126888 (H.G.M.) from the NCI, and a Merit award I01BX001363 (H.G.M.) from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: The authors have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Shields MA, Dangi-Garimella S, Redig AJ, Munshi HG. Biochemical role of the collagen-rich tumour microenvironment in pancreatic cancer progression. The Biochemical journal. 2012;441:541–52. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maitra A, Hruban RH. Pancreatic cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:157–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardeesy N, DePinho RA. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:897–909. doi: 10.1038/nrc949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, Gopinathan A, McIntyre D, Honess D, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324:1457–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR. Enzymatic Targeting of the Stroma Ablates Physical Barriers to Treatment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:418–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dangi-Garimella S, Krantz SB, Barron MR, Shields MA, Heiferman MJ, Grippo PJ, et al. Three-Dimensional Collagen I Promotes Gemcitabine Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer through MT1-MMP-Mediated Expression of HMGA2. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1019–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vonlaufen A, Joshi S, Qu C, Phillips PA, Xu Z, Parker NR, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells: partners in crime with pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2085–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apte MV, Haber PS, Applegate TL, Norton ID, McCaughan GW, Korsten MA, et al. Periacinar stellate shaped cells in rat pancreas: identification, isolation, and culture. Gut. 1998;43:128–33. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachem MG, Schneider E, Gross H, Weidenbach H, Schmid RM, Menke A, et al. Identification, culture, and characterization of pancreatic stellate cells in rats and humans. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:421–32. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachem MG, Schunemann M, Ramadani M, Siech M, Beger H, Buck A, et al. Pancreatic carcinoma cells induce fibrosis by stimulating proliferation and matrix synthesis of stellate cells. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:907–21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ottaviano AJ, Sun L, Ananthanarayanan V, Munshi HG. Extracellular matrix-mediated membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase expression in pancreatic ductal cells is regulated by transforming growth factor-beta1. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7032–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krantz SB, Shields MA, Dangi-Garimella S, Cheon EC, Barron MR, Hwang RF, et al. MT1-MMP cooperates with Kras(G12D) to promote pancreatic fibrosis through increased TGF-beta signaling. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:1294–304. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friess H, Yamanaka Y, Buchler M, Ebert M, Beger HG, Gold LI, et al. Enhanced expression of transforming growth factor beta isoforms in pancreatic cancer correlates with decreased survival. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1846–56. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91084-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0901557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2011;378:607–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krantz SB, Shields MA, Dangi-Garimella S, Munshi HG, Bentrem DJ. Contribution of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Cancer Stem Cells to Pancreatic Cancer Progression. J Surg Res. 2012;173:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald OG, Maitra A, Hruban RH. Human correlates of provocative questions in pancreatic pathology. Adv Anat Pathol. 2012;19:351–62. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e318273f998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dangi-Garimella S, Krantz SB, Shields MA, Grippo PJ, Munshi HG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and pancreatic cancer progression. 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hotz B, Arndt M, Dullat S, Bhargava S, Buhr HJ, Hotz HG. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition: expression of the regulators snail, slug, and twist in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4769–76. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin T, Wang C, Liu T, Zhao G, Zha Y, Yang M. Expression of snail in pancreatic cancer promotes metastasis and chemoresistance. J Surg Res. 2007;141:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boutet A, De Frutos CA, Maxwell PH, Mayol MJ, Romero J, Nieto MA. Snail activation disrupts tissue homeostasis and induces fibrosis in the adult kidney. EMBO J. 2006;25:5603–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowe RG, Lin Y, Shimizu-Hirota R, Hanada S, Neilson EG, Greenson JK, et al. Hepatocyte-Derived Snail1 Propagates Liver Fibrosis Progression. Mol Cell Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1128/MCB.01218-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grippo PJ, Nowlin PS, Demeure MJ, Longnecker DS, Sandgren EP. Preinvasive pancreatic neoplasia of ductal phenotype induced by acinar cell targeting of mutant Kras in transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2016–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guerra C, Schuhmacher AJ, Cañamero M, Grippo PJ, Verdaguer L, Pérez-Gallego L, et al. Chronic pancreatitis is essential for induction of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by K-Ras oncogenes in adult mice. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun L, Diamond ME, Ottaviano AJ, Joseph MJ, Ananthanarayan V, Munshi HG. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 promotes matrix metalloproteinase-9-mediated oral cancer invasion through snail expression. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:10–20. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shields MA, Krantz SB, Bentrem DJ, Dangi-Garimella S, Munshi HG. Interplay between beta1-Integrin and Rho Signaling Regulates Differential Scattering and Motility of Pancreatic Cancer Cells by Snail and Slug Proteins. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:6218–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.308940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shields MA, Dangi-Garimella S, Krantz SB, Bentrem DJ, Munshi HG. Pancreatic Cancer Cells Respond to Type I Collagen by Inducing Snail Expression to Promote Membrane Type 1 Matrix Metalloproteinase-dependent Collagen Invasion. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:10495–504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.195628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang RF, Moore T, Arumugam T, Ramachandran V, Amos KD, Rivera A, et al. Cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts promote pancreatic tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2008;68:918–26. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward ST, Dangi-Garimella S, Shields MA, Collander BA, Siddiqui MA, Krantz SB, et al. Ethanol differentially regulates snail family of transcription factors and invasion of premalignant and malignant pancreatic ductal cells. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:2966–73. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munshi HG, Wu YI, Mukhopadhyay S, Ottaviano AJ, Sassano A, Koblinski JE, et al. Differential regulation of membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase activity by ERK 1/2- and p38 MAPK-modulated tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 2 expression controls transforming growth factor-beta1-induced pericellular collagenolysis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39042–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuveson DA, Neoptolemos JP. Understanding metastasis in pancreatic cancer: a call for new clinical approaches. Cell. 2012;148:21–3. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhim AD, Mirek ET, Aiello NM, Maitra A, Bailey JM, McAllister F, et al. EMT and dissemination precede pancreatic tumor formation. Cell. 2012;148:349–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braganza JM, Lee SH, McCloy RF, McMahon MJ. Chronic pancreatitis. Lancet. 2011;377:1184–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61852-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li N, Grivennikov SI, Karin M. The Unholy Trinity: Inflammation, Cytokines, and STAT3 Shape The Cancer Microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:429–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bronson RT, Strauss W, Wheeler W. Pancreatic ectasia in uremic macaques. Am J Pathol. 1982;106:342–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grippo PJ, Fitchev PS, Bentrem DJ, Melstrom LG, Dangi-Garimella S, Krantz SB, et al. Concurrent PEDF deficiency and Kras mutation induce invasive pancreatic cancer and adipose-rich stroma in mice. Gut. 2012;61:1454–64. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jamora C, Lee P, Kocieniewski P, Azhar M, Hosokawa R, Chai Y, et al. A signaling pathway involving TGF-beta2 and snail in hair follicle morphogenesis. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du F, Nakamura Y, Tan TL, Lee P, Lee R, Yu B, et al. Expression of snail in epidermal keratinocytes promotes cutaneous inflammation and hyperplasia conducive to tumor formation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10080–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy HK, Iversen P, Hart J, Liu Y, Koetsier JL, Kim Y, et al. Down-regulation of SNAIL suppresses MIN mouse tumorigenesis: modulation of apoptosis, proliferation, and fractal dimension. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1159–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Massoumi R, Kuphal S, Hellerbrand C, Haas B, Wild P, Spruss T, et al. Down-regulation of CYLD expression by Snail promotes tumor progression in malignant melanoma. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2009;206:221–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mallen-St Clair J, Soydaner-Azeloglu R, Lee KE, Taylor L, Livanos A, Pylayeva-Gupta Y, et al. EZH2 couples pancreatic regeneration to neoplastic progression. Genes & Development. 2012;26:439–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.181800.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herranz N, Pasini D, Diaz VM, Franci C, Gutierrez A, Dave N, et al. Polycomb complex 2 is required for E-cadherin repression by the Snail1 transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4772–81. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00323-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tong ZT, Cai MY, Wang XG, Kong LL, Mai SJ, Liu YH, et al. EZH2 supports nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell aggressiveness by forming a co-repressor complex with HDAC1/HDAC2 and Snail to inhibit E-cadherin. Oncogene. 2012;31:583–94. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahadevan D, Von Hoff DD. Tumor-stroma interactions in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1186–97. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karsdal MA, Larsen L, Engsig MT, Lou H, Ferreras M, Lochter A, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-dependent activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta controls the conversion of osteoblasts into osteocytes by blocking osteoblast apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44061–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010;141:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haraguchi M, Okubo T, Miyashita Y, Miyamoto Y, Hayashi M, Crotti TN, et al. Snail regulates cell-matrix adhesion by regulation of the expression of integrins and basement membrane proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23514–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801125200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mu D, Cambier S, Fjellbirkeland L, Baron JL, Munger JS, Kawakatsu H, et al. The integrin αvβ8 mediates epithelial homeostasis through MT1-MMP–dependent activation of TGF-β1. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;157:493–507. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munger JS, Huang X, Kawakatsu H, Griffiths MJD, Dalton SL, Wu J, et al. A Mechanism for Regulating Pulmonary Inflammation and Fibrosis: The Integrin αvβ6 Binds and Activates Latent TGF β1. Cell. 1999;96:319–28. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Munger JS, Sheppard D. Cross talk among TGF-beta signaling pathways, integrins, and the extracellular matrix. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a005017. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Aarsen LA, Leone DR, Ho S, Dolinski BM, McCoon PE, LePage DJ, et al. Antibody-mediated blockade of integrin alpha v beta 6 inhibits tumor progression in vivo by a transforming growth factor-beta-regulated mechanism. Cancer research. 2008;68:561–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garamszegi N, Garamszegi SP, Samavarchi-Tehrani P, Walford E, Schneiderbauer MM, Wrana JL, et al. Extracellular matrix-induced transforming growth factor-beta receptor signaling dynamics. Oncogene. 2010;29:2368–80. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.