Abstract

Purpose

The American Academy of Pediatrics no longer recommends a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) for children aged 2 to 24 months presenting with their first urinary tract infection (UTI) if renal-bladder ultrasound (RBUS) is normal. Our goal was to identify factors associated with abnormal imaging and recurrent pyelonephritis for this population.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively evaluated children diagnosed with first episode of pyelonephritis between 2 to 24 months using de-identified electronic medical record data from an institutional database. Data included age at first UTI, gender, race/ethnicity, need for hospitalization, intravenous antibiotic use, history of abnormal prenatal ultrasound, RBUS and VCUG results, UTI recurrence and surgical intervention. Risk factors for abnormal imaging and UTI recurrence were analyzed with univariate logistic regression, chi square and survival analysis.

Results

We identified 174 patients. Of 154 RBUS performed, 59 (38%) were abnormal. Abnormal prenatal ultrasound (p=0.01) and need for hospitalization (p=0.02) predicted abnormal RBUS. Of the 95 patients with normal RBUS, 84 had a VCUG. Vesicoureteral reflux was more likely in Caucasians (p=0.003), females (p=0.02) and older patients (p=0.04). Despite normal RBUS, 23 of 84 (24%) patients had dilating vesicoureteral reflux. Of the 95 patients with normal RBUS, 14 (15%) had recurrent pyelonephritis and 7 (7%) went on to surgical intervention.

Conclusions

Despite a normal RBUS after first episode of pyelonephritis, a child may still have vesicoureteral reflux, recurrent pyelonephritis, and need for surgical intervention. If VCUG is deferred, parents should be counseled regarding these risks.

Keywords: Pediatrics, Urinary Tract Infections, Pyelonephritis, Vesico-Ureteral Reflux

INTRODUCTION

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common bacterial disease of childhood and one of the main causes of acquired renal scarring. Over half of children with UTI will have acute-phase parenchymal changes on renal scintigraphy with technetium-99m–labeled dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA). A small proportion will have persistent renal changes.1 Diagnostic imaging of the urinary tract in children after first febrile UTI has been accepted practice for many years; however the best initial approach has been debated. Renal bladder ultrasonography (RBUS), voiding cystourethrography (VCUG), and DMSA scan have been the core imaging methods.

In September 2011, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) presented an updated clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months of age. The AAP no longer recommends a VCUG to look for vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) in children 2 to 24 months presenting with their first UTI if RBUS is normal.2 Their meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials3-8 failed to show efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis. Antibiotic prophylaxis has decreased recurrent febrile UTI rates8 and new onset renal scarring9 in girls with higher grades of VUR in the Swedish Reflux Trial. There is concern that implementation of the new guideline may harm the subset of children who may benefit from earlier VUR diagnosis and treatment.

We hypothesized that children diagnosed with their first UTI from 2 to 24 months of age represent a heterogeneous group with varying risks for recurrent pyelonephritis. Our objectives were to identify risk factors associated with recurrent pyelonephritis in this age group and in the subset of patients with normal RBUS who would no longer undergo additional imaging for VUR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After receiving institutional review board approval, we identified patients in the Synthetic Derivative (SD) database at Vanderbilt University Medical Center who were less than 5 years old and had been assigned an ICD-9 diagnosis code of 590.0 for pyelonephritis. The SD database is a research tool developed to enable studies with de-identified clinical data. The SD collection includes information extracted from the electronic medical record. The system generates a unique, 512 bit (128 character) code that serves as a Research Unique Identifier and is used to index de-identified computer data. The SD contains approximately 2 million total records, with highly detailed longitudinal clinical data for approximately one million subjects. The database incorporates data from multiple sources and includes diagnostic and procedure codes (ICD-9 and CPT), basic demographics (age, gender, race), text from clinical care including discharge summaries, nursing notes, progress notes, history and physical, problem lists and multi-disciplinary assessments, laboratory values, electrocardiogram diagnoses, clinical text and electronically derived trace values, and inpatient medication orders. All clinical data are updated regularly to include patients new to Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and therefore the SD, and to append new data to clinical records of existing patients as they continue to access care at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Thus, the resource is entirely suitable for mining information relative to disease progression over time.10

We limited our analyses to children diagnosed with first UTI between 2 and 24 months of age. We used a text search to identify and exclude patients with ICD-9 miscoding without any textual reference to UTI. We documented fever associated with all first and recurrent episodes of UTI. We collected demographic information including gender, circumcision status in boys, race/ethnicity, age at first UTI, as well as need for hospitalization, use of intravenous antibiotics, history of abnormal prenatal ultrasound, RBUS results, VCUG results, presence of recurrent UTI, and incidence of surgical intervention. If VCUG showed bilateral VUR, we categorized grade as the higher of the two sides.

Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at Vanderbilt University. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing: 1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for importing data from external sources.11

We assessed risk factors for abnormal RBUS with univariate logistic regression for continuous variables and chi square test for categorical variables. We used survival analysis to study risk factors for febrile UTI recurrence. We defined time in the study as the time elapsed between first UTI diagnosis either to last documented clinical contact by primary care or pediatric urology in those who remained free of infection or to time of febrile UTI recurrence after first UTI diagnosis.

We also analyzed our subset of patients who had a normal RBUS after their first UTI diagnosis. We assessed risk factors for VUR in children with a normal RBUS using univariate logistic regression for continuous variables and chi square test for categorical variables. We used survival analysis with log-rank test of equality to analyze risk factors for recurrent febrile UTI in this subset of patients.

RESULTS

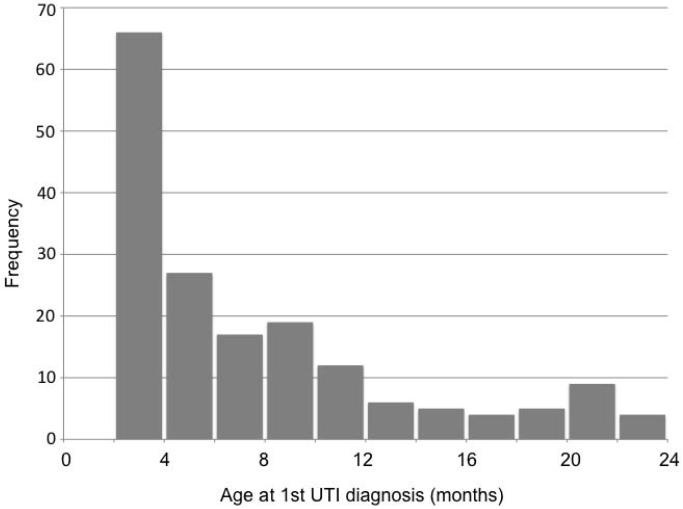

A total of 174 patients were included. Time of first UTI was between June 2006 and July 2010. Most patients were Caucasian (56%) and female (78%). Of the 174 children, 11 had known prenatal ultrasound abnormalities including hydronephrosis in 7, spina bifida in 1, solitary kidney with oligohydramnios in 1 and unknown abnormalities in 2. All patients in our study had an associated emergency department visit and/or inpatient admission associated with their first UTI. About half of the patients in our patient population had documented inpatient admission at our institution (47%) for their first UTI. Route of administration of antibiotics was a combination of intravenous and oral in 96, intravenous only in 11, oral only in 36 and unknown in 31. More than half received intravenous antibiotics (61%) for at least part of their treatment. The median age at first UTI diagnosis was 5.7 months [range: 2.0 – 23.3 months]. The age distribution was skewed to younger ages as shown in Figure 1. Last documented follow-up was April 2012. Median follow-up was 19.5 months [range: 0.2 – 64.5 months].

Figure 1.

Age distribution at diagnosis of first episode of pyelonephritis.

Of these 174 patients, 154 (89%) had RBUS after pyelonephritis. Abnormal RBUS in 59 patients included isolated hydronephrosis in 41; hydronephrosis with associated anomalies such as dysplasia, ureterocele or solitary kidney in 8; pyelonephritis/abscess in 5; cortical scarring in 2; isolated ureterocele in 1; solitary kidney in 1; and other unspecified anomaly in 1. Table 1a lists risk factors for abnormal RBUS. Both hospitalization for the first UTI (p=0.02) and known prenatal ultrasound abnormality (p=0.01) were significant risk factors. However, 53 (36%) of the 147 patients with reported normal prenatal ultrasounds went on to have abnormal RBUS after first UTI.

Table 1.

Risk factors for abnormal RBUS (A) and recurrent febrile UTI (B) in all 174 patients

| A. | |

|---|---|

| Risk factor for abnormal RBUS | p value |

| Age at 1st UTI diagnosis | 0.63 |

| Female sex | 0.65 |

| Race / ethnicity: Caucasian vs non-Caucasian | 0.90 |

| Prenatal ultrasound abnormality | 0.01 |

| Hospitalization for UTI | 0.02 |

| Intravenous antibiotics for UTI | 0.14 |

| B. | |

|---|---|

| Risk factor for recurrent febrile UTI | p value |

| Age at 1st UTI diagnosis | 0.32 |

| Female sex | 0.04 |

| Race / ethnicity: Caucasian vs non-Caucasian | 0.69 |

| Abnormal RBUS | 0.06 |

| Hospitalization for UTI | 0.63 |

| Intravenous antibiotics for UTI | 0.67 |

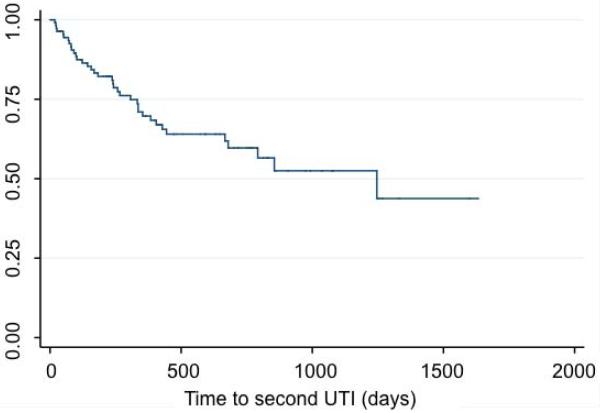

Recurrent pyelonephritis episodes were diagnosed in 37 (21%) patients. Of the 37 patients, there was documented intravenous antibiotic use in 20 (54%) and hospital inpatient admission in 12 (32%). We evaluated risk factors of UTI recurrence. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve for febrile UTI recurrence after the first diagnosis of UTI. We analyzed risk factors associated with UTI recurrence in Table 1b. The only risk factor we identified associated with recurrence was female gender (p=0.04). Of the 37 patients with recurrent pyelonephritis, 34 (92%) were girls. Normal RBUS was not associated with decreased rates of recurrent pyelonephritis.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for febrile UTI recurrence after the first diagnosis of pyelonephritis.

We evaluated the association of circumcision and UTI. Of the 39 boys with first UTI between 2 and 24 months of age, 22 were uncircumcised, 8 were circumcised and 9 had unknown circumcision status. The proportion of boys who are uncircumcised in our study is considerably higher than in our general male pediatric population. Of the 39 boys, 5 uncircumcised boys went on to have a second episode of pyelonephritis. There were no further documented episodes of pyelonephritis in circumcised boys or boys with unknown circumcision status. Of the 22 uncircumcised boys, 6 had circumcisions after their first UTI. None of these boys with delayed circumcision had recurrent pyelonephritis.

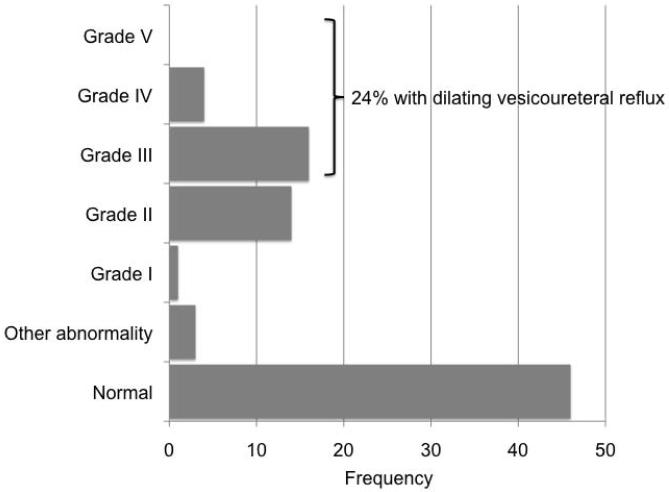

We then evaluated the subset of 95 patients with normal RBUS. This population would undergo expectant management without VCUG by the updated AAP clinical practice guideline. Of these 95 patients, 84 (88%) had a VCUG. Figure 3 presents the VCUG results in this population with normal RBUS. Of the 84 with VCUG results and normal RBUS, 20 (24%) had dilating VUR. Table 2 shows VUR was more likely in Caucasians (p=0.003) and females (0.04). Surprisingly, VUR was more likely in older patients (p=0.04). Of the 95 patients with a normal RBUS, 14 (15%) had a second episode of pyelonephritis and 7 (7%) went on to have surgical intervention for the indication of persistent VUR with breakthrough febrile UTI while on continuous antibiotic prophylaxis. Of these patients who had recurrent UTI, 10 of 14 had a diagnosis of VUR. When we performed a survival analysis on this subset of patients with normal RBUS, we were unable to identify any significant associated risk factors for recurrent pyelonephritis.

Figure 3.

VCUG results in patients with normal RBUS after the first diagnosis of pyelonephritis.

Table 2.

Risk factors for VUR in patients with normal RBUS after first UTI

| Risk factor | p value |

|---|---|

| Older age at 1st UTI diagnosis | 0.04 |

| Female sex | 0.02 |

| Race / ethnicity: Caucasian vs non-Caucasian | 0.003 |

| Hospitalization for UTI | 0.21 |

| Intravenous antibiotics for UTI | 0.29 |

DISCUSSION

The publication of the revised AAP clinical practice guideline 2 for the diagnosis and management of febrile UTIs in infants and children 2 to 24 months has generated significant debate. Because the meta-analysis suggested that prophylaxis does not prevent recurrent febrile UTI, the guideline committee questioned the rationale of performing a VCUG after an initial febrile UTI. The AAP Section on Urology has expressed concern that the recommendation for RBUS but not VCUG after febrile UTI is based on a flawed interpretation of limited data. Methodological weaknesses include bag urine specimens, no documented circumcision status for boys, no discussion of the role of bowel and bladder habits, incomplete assessment of treatment compliance and incomplete assessment of renal scarring. The major concern is that the new AAP clinical practice guideline will delay beneficial treatment for a subset of children. The updated clinical practice guideline is largely based on patients with low grade VUR. Because the studies were not powered for individual grades of VUR, the combined analysis may obscure benefits for patients with higher grades of VUR.

It would be a mistake to infer from the AAP clinical practice guideline that normal RBUS rules out dilating VUR or predicts against recurrent pyelonephritis. Approximately one-fourth of our patients with normal RBUS after initial pyelonephritis had dilating VUR. We also found that normal RBUS was not associated with decreased rates of pyelonephritis. In our study 15% of children with normal RBUS after first febrile UTI go on to have recurrent pyelonephritis. This recurrence was a significant event for families often including ED visits, inpatient hospitalization, and/or intravenous antibiotics. Because our database was limited to our institution, we could not capture episodes of pyelonephritis treated at outside facilities unless families reported the event to a primary care clinic within our institution or to our pediatric urology clinic. As a result, pyelonephritis recurrence rates may be underestimated.

Interestingly, even before the current AAP practice guideline was published, we found that only 88% of patients who had a normal RBUS underwent VCUG. Low compliance with imaging recommendations of the recently replaced AAP practice guideline has previously been reported – as low as 61% in an academic setting 12 and 28% in a Medicaid population.13 With VCUG no longer part of the initial workup for febrile UTI, we hope that children will not be allowed to undergo multiple episodes of pyelonephritis before undergoing imaging for VUR.

Children with pyelonephritis represent a heterogeneous population with varying risk factors for recurrence and renal scarring. Better risk stratification would decrease over diagnosis and overtreatment of VUR while preventing delay of beneficial treatment. The current AAP clinical practice guideline recommendations do not adequately address these individual differences. In our study we found that girls were more likely to have UTI recurrence and VUR. Patient gender is one of many predictors likely to play a role in how UTI and VUR affect each individual patient. Currently there are no widely accepted predictors of VUR, recurrent pyelonephritis and renal scarring in this age range. Investigators have proposed using biomarkers such as procalcitonin which has been found to be predictive of renal scarring and high grade VUR, but these adjuncts to clinical decision making are still being validated.14, 15

Our study could not assess several factors known to be associated with VUR outcomes. Because the patients in our study did not have routine DMSA scans, we cannot comment on the incidence of renal scarring. In 2007 the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence presented similar UTI guidelines that limited the use of VCUG only to those patients who had an abnormal RBUS. 16 Tse at al. analyzed the effect of these guidelines in infants less than 6 months of age (98 patients, 196 kidneys) and found that 22 scarred kidneys would have been missed.17 We could not assess bladder and bowel dysfunction in toilet trained children. In our pediatric urology clinic, we use a standardized questionnaire to evaluate bladder and bowel function.18 Although these scanned questionnaires become part of the patient’s medical record, they are not currently imported into the SD database. Bladder and bowel dysfunction was not addressed in any of the emergency department or inpatient clinical care records. Similarly, we could not reliably assess family history of childhood UTIs, VUR and renal disease. We did not believe that directed questioning about family history of nephrologic or urologic problems would be standardized across the emergency department, inpatient and pediatric urology clinic settings.

After a first febrile UTI, if VCUG is deferred, a normal RBUS does not exclude recurrent pyelonephritis, high grade VUR, renal scarring or possible need for surgical intervention. A second pyelonephritis episode may involve intravenous antibiotics and hospital admission. A subset of these patients may benefit from early diagnosis of VUR and antibiotic prophylaxis. Families should be made aware of both the benefits and risks of imaging for VUR. The ongoing Randomized Intervention for Children with Vesicoureteral Reflux study (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00405704) should offer useful information that may significantly influence the next set of guidelines regarding antibiotic prophylaxis.19

CONCLUSIONS

We agree that RBUS should be performed after first febrile UTI in children 2 to 24 months as over one-third had abnormal ultrasound findings. More importantly, despite a normal RBUS, a child may still have: 1) recurrent pyelonephritis, 2) high grade VUR, and/or 3) VUR that may ultimately undergo surgical intervention. A normal RBUS is not a guarantee against medically significant VUR. At this point we do not have a way to predict these patients. Although we found that female gender was associated with recurrent pyelonephritis when we evaluated all patients with febrile UTI, we could not identify specific risk factors for recurrence in patients with normal RBUS. If VCUG is deferred, families should be counseled regarding the risk of recurrent pyelonephritis and potential need for urologic intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The use of REDCap and the Synthetic Derivative was supported by CTSA award No. UL1TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: DISCLAIMER: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our subscribers we are providing this early version of the article. The paper will be copy edited and typeset, and proof will be reviewed before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to The Journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaikh N, Ewing AL, Bhatnagar S, et al. Risk of renal scarring in children with a first urinary tract infection: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1084. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts KB. Urinary tract infection: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics. 2011;128:595. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pennesi M, Travan L, Peratoner L, et al. Is antibiotic prophylaxis in children with vesicoureteral reflux effective in preventing pyelonephritis and renal scars? A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1489. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garin EH, Olavarria F, Garcia Nieto V, et al. Clinical significance of primary vesicoureteral reflux and urinary antibiotic prophylaxis after acute pyelonephritis: a multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:626. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montini G, Rigon L, Zucchetta P, et al. Prophylaxis after first febrile urinary tract infection in children? A multicenter, randomized, controlled, noninferiority trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1064. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roussey-Kesler G, Gadjos V, Idres N, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in children with low grade vesicoureteral reflux: results from a prospective randomized study. The Journal of urology. 2008;179:674. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craig JC, Simpson JM, Williams GJ, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis and recurrent urinary tract infection in children. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:1748. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandstrom P, Esbjorner E, Herthelius M, et al. The Swedish reflux trial in children: III. Urinary tract infection pattern. The Journal of urology. 2010;184:286. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandstrom P, Neveus T, Sixt R, et al. The Swedish reflux trial in children: IV. Renal damage. The Journal of urology. 2010;184:292. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roden DM, Pulley JM, Basford MA, et al. Development of a large-scale de-identified DNA biobank to enable personalized medicine. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2008;84:362. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009;42:377. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah L, Mandlik N, Kumar P, et al. Adherence to AAP practice guidelines for urinary tract infections at our teaching institution. Clinical pediatrics. 2008;47:861. doi: 10.1177/0009922808319962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen AL, Rivara FP, Davis R, et al. Compliance with guidelines for the medical care of first urinary tract infections in infants: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1474. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheu JN, Chang HM, Chen SM, et al. The role of procalcitonin for acute pyelonephritis and subsequent renal scarring in infants and young children. The Journal of urology. 2011;186:2002. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leroy S, Romanello C, Galetto-Lacour A, et al. Procalcitonin is a predictor for high-grade vesicoureteral reflux in children: meta-analysis of individual patient data. The Journal of pediatrics. 2011;159:644. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Excellence, N. I. f. H. a. C.: Urinary tract infection in children. NICE; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tse NK, Yuen SL, Chiu MC, et al. Imaging studies for first urinary tract infection in infants less than 6 months old: can they be more selective? Pediatric nephrology. 2009;24:1699. doi: 10.1007/s00467-009-1203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afshar K, Mirbagheri A, Scott H, et al. Development of a symptom score for dysfunctional elimination syndrome. The Journal of urology. 2009;182:1939. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chesney RW, Carpenter MA, Moxey-Mims M, et al. Randomized Intervention for Children With Vesicoureteral Reflux (RIVUR): background commentary of RIVUR investigators. Pediatrics. 2008;122(Suppl 5):S233. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1285c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]