Abstract

Activating point mutations in K-RAS are extremely common in cancers of the lung, colon, and pancreas and are highly predictive of poor therapeutic response. One potential strategy for overcoming the deleterious effects of mutant K-RAS is to alter its post-translational modification. While therapies targeting farnesylation have been explored, and ultimately failed, the therapeutic potential of targeting other modifications remains to be seen. We recently demonstrated that acetylation of lysine 104 attenuates K-RAS transforming activity by interfering with GEF-induced nucleotide exchange. Here, we have identified HDAC6 and SIRT2 as deacetylases that regulate the acetylation state of K-RAS in cancer cells. By extension, inhibition of either of these enzymes dramatically affects the growth properties of cancer cell lines expressing mutationally activated K-RAS. These results suggest that therapeutic targeting of HDAC6 and/or SIRT2 may represent a new way to treat cancers expressing mutant forms of K-RAS.

Introduction

KRAS is the most commonly mutated oncogene in cancer, with a particularly high prevalence in cancers with high mortality (1). K-RAS protein functions as a monomeric GTPase and can be locked into its GTP-bound activated state by missense point mutation, most commonly at amino acids 12, 13, 61, or 146 (2). Like all members of the RAS superfamily, K-RAS protein function is tightly regulated by post-translational modification. Both splice forms of K-RAS (K-RAS4A and K-RAS4B) are farnesylated on a C-terminal cysteine and K-RAS4A is subsequently palmitoylated (3). These lipidation events regulate K-RAS function by promoting its association with the plasma membrane, which is required for its interaction with downstream effectors. Other post-translational modifications regulate K-RAS activity more directly. For example, mono-ubiquitination of lysine 147 potentiates GTP binding by K-RAS and, therefore, ubiquitinated K-RAS exhibits enhances binding to RAF and PI3K (4). Recently, we found that K-RAS is acetylated on lysine 104 and that acetylated K-RAS is resistant to guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF)-mediated nucleotide exchange (5). Mutant K-RAS that is acetylated cannot re-load GTP in an efficient manner to maintain a fully activated state, resulting in attenuated transforming activity (5).

Because acetylation regulates the oncogenic activity of K-RAS, modulation of K-RAS acetylation could constitute a therapeutic strategy for cancers expressing mutationally activated forms of the protein. Protein deacetylation at lysine residues is mediated by highly conserved enzymes including the class I/II histone deacetylases (HDAC1–10) and the class III sirtuin deacetylase family (SIRT1–7). Members of both deacetylase families are found in multiple compartments of the cell and can have both histone and non-histone substrates (6). Sirtuins are distinct from HDACs in that they have an absolute requirement for the co-substrate NAD in their deacetylation reaction, linking Sirtuin catalytic activity with the metabolic status of the cell (7). Here, we have identified HDAC6 and SIRT2 as two enzymes that regulate the acetylation state of K-RAS and we have demonstrated that inhibition of these enzymes affects transformation of cells expressing mutationally activated K-RAS.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines, drug treatments, and immunoprecipitations

SW480, 293T, NIH3t3, H2009, and H460 cells were obtained from ATCC. DLD-1 and DKs-8 cells were obtained from the laboratory of Dr. Robert Coffey (Vanderbilt University). NIH3T3 cells stably over-expressing mutant forms of K-RAS were described previously (5). Immunoprecipitations for acetylated RAS and interactions between RAS and Sirtuins or HDACs were performed as described previously (5, 8). Western blots were detected with ECL Plus (Pierce) on film. Bands were quantified using ImageJ. In cases where RAS acetylation assays were done after pretreatment with a deacetylase inhibitor – Trichostatin A (TSA, 1 µM), Tubastatin A (TubA, 10 µM), Nicotinamide (NAM, 1.65 mM) – cells were pre-treated for 1 hour.

Short-term knockdown was achieved by treating cells with Dharmacon SMARTpool siRNAs targeting KRAS, HDAC1, HDAC6, SIRT1, or SIRT2. Long-term knockdown was achieved by infecting cells with pSICOR lentivirus (9) carrying shRNAs targeting KRAS, HDAC6, or SIRT2. All knockdowns were confirmed by western blotting (Supplemental Fig. 1). Cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Transformation assays

Short-term viability assays were performed by growing cells in 96-well plates in the presence or absence of siRNA. Viability was quantified after 72 hours by staining with Syto60 (Invitrogen). Plates were scanned and analyzed on a LiCor Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. For growth curves, cells were plated at 1 × 105/well in 6 well dishes in media containing 10% FBS and cells were counted after 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 days using a hemocytometer. For colony forming assays, 200 cells were plated into each well of a 6-well dish in media containing 2% FBS. After two weeks, colonies were stained with 0.2% crystal violet and analyzed using IMAGE J software. All experiments were performed twice, each time with technical triplicates. Statistical analyses were performed using the Mstat computer program.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

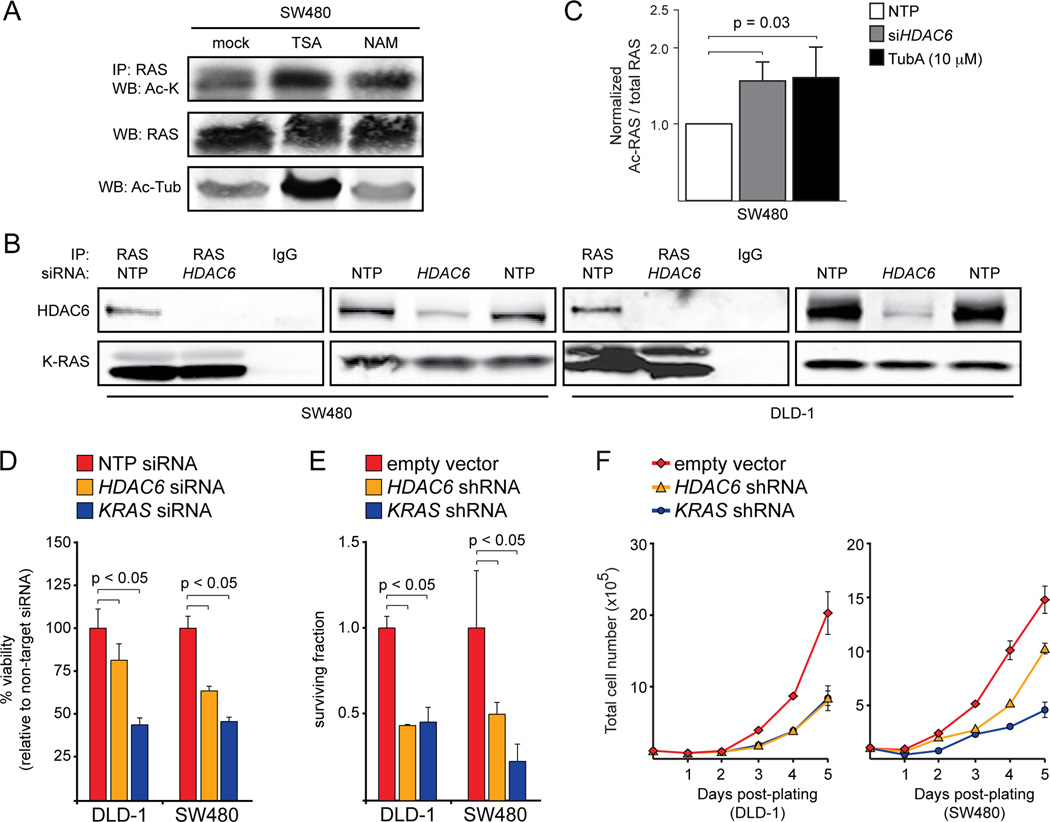

To gain insight into the enzymes that regulate RAS acetylation, we treated SW480 colorectal cancer (CRC) cells with trichostatin A (TSA), an inhibitor of class I/II deacetylases (DACs). We found that TSA treatment increased the levels of acetylated RAS (Fig. 1A), suggesting that RAS acetylation is regulated by at least one member of the class I/II family. To identify the family member that regulates RAS acetylation, we took a candidate approach and looked for DACs that co-immunoprecipitated with RAS. We found that HDAC6 (Fig. 1B), but not HDAC1 (Fig. S2A), co-immunoprecipitated with endogenous RAS in two different CRC cell lines. Consistent with the notion that HDAC6 regulates RAS acetylation, cells treated with siRNA for HDAC6 or with Tubastatin A (TubA), an HDAC6-specific inhibitor, exhibited significantly elevated levels of acetylated RAS (Fig. 1C). These observations suggest that RAS acetylation is controlled, at least in part, by HDAC6.

Figure 1.

HDAC6 regulates K-RAS acetylation and oncogenicity. A, Effect of TSA and NAM treatment on RAS acetylation. Treatment of SW480 CRC cells with TSA (1 µM) or NAM (1.65 mM) for 1 hour led to an increase in acetylated RAS. Acetylated α-Tubulin was used as a control. Unlike TSA, NAM treatment did not affect the acetylation of α-Tubulin. B, HDAC6 interacts with RAS. HDAC6 could be detected by western blot after immunoprecipitation of endogenous RAS in DLD-1 or SW480 CRC cells. Knockdown of HDAC6 prevented the co-immunoprecipitation. C, Effect of HDAC6 inhibition on RAS acetylation. Inhibition of HDAC6 via siRNA-mediated knockdown or treatment with TubA (10 µM) led to a significant increase in acetylated RAS. D, Effect of HDAC6 knockdown on viability. Acute knockdown of HDAC6 significantly reduced viability of CRC cells in a short-term (3 days) assay. Knockdown of KRAS was used as a positive control. Data were normalized to cells treated with a non-targeted pool (NTP) siRNA. E, Effect of HDAC6 knockdown on clonogenic survival. Chronic HDAC6 knockdown, like KRAS knockdown, significantly affected colony formation in CRC cells. Cells infected with empty shRNA vector were used as a negative control. Data were normalized to cells infected with empty shRNA vector. F, Effect of HDAC6 knockdown on proliferation. The proliferation of CRC cells with stable HDAC6 or KRAS knockdown was reduced compared to cells infected with empty vector.

Although HDAC6 was first identified as a tubulin deacetylase (10–12), it has many other cytoplasmic substrates and interacting proteins, including cortactin, HSP90, survivin, GSK3β, and PKCα (13). Ours is the first study to link HDAC6 to RAS acetylation, however. HDAC6 performs both deacetylase-dependent and deacetylase-independent functions and not all of its interacting partners are substrates. For example, HDAC6 is a substrate for PKCβ, which regulates its ability to deacetylate β-catenin, but HDAC6 is not known to deacetylate PKCα (14). In the case of RAS, knockdown or inhibition of HDAC6 does affect is acetylation state, suggesting that RAS may be a direct substrate.

We have previously demonstrated that acetylation of K104 negatively affects K-RAS-induced transformation (5). If HDAC6 controls RAS acetylation, we expected that knockdown would affect the growth of cells expressing mutant forms of K-RAS. To test this hypothesis, we measured the viability of K-RAS mutant CRC cells after acute knockdown of HDAC6. Similar to knockdown of KRAS itself, HDAC6 knockdown reduced the viability of CRC cells in a short-term growth assay (Fig. 1D). In longer-term colony forming and proliferation assays, chronic knockdown of KRAS and HDAC6 also had significant deleterious effects (Fig. 1E,F and Fig. S2B). Altogether, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that HDAC6 modulates the oncogenic function of mutant K-RAS by regulating its acetylation state.

Other studies have linked HDAC6 to cancer. HDAC6 is an estrogen-responsive gene and its over-expression in breast cancer may play an important role in malignant progression (15). A more direct role for HDAC6 in cancer was revealed when HDAC6 null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were found to be resistant to H-RAS-induced transformation and that HDAC6 null animals were resistant to DMBA-induced skin carcinogenesis, which also involves mutation of H-RAS (16). In these studies, loss of HDAC6 was associated with attenuated activation of PI3K and MAPK signaling downstream of mutant H-RAS, suggesting that loss of HDAC6 might function at the level of RAS itself (16). This previous study did not, however, make a direct connection between HDAC6 and RAS acetylation. And while our study focused on mutationally activated K-RAS, which is more commonly mutated in human cancers than is H-RAS, lysine 104 is conserved in all RAS isoforms (5). Altogether, these results suggest that the oncogenic properties of all RAS family members might be regulated by HDAC6.

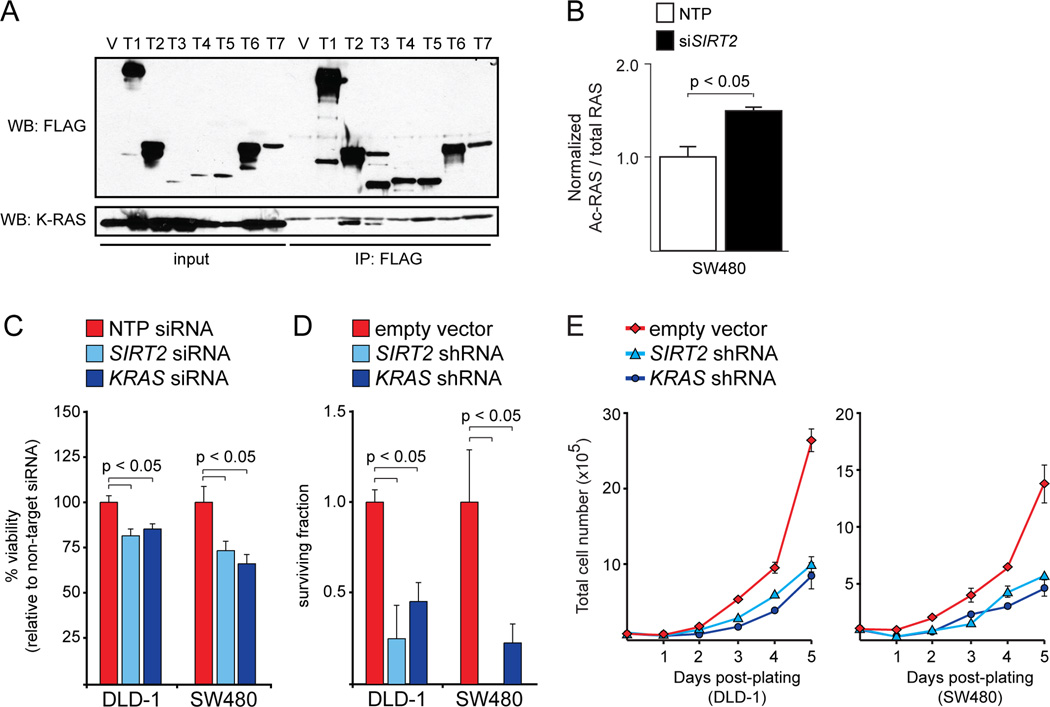

While we initially demonstrated that TSA increased RAS acetylation, we noted that nicotinamide (NAM), a class III DAC inhibitor, had a similar effect in SW480 cells (Fig. 1A). To identify the class III deacetylase that regulates RAS acetylation, we looked for interaction between K-RAS and members of the Sirtuin protein family. We found that K-RAS interacted with SIRT2 and, to a lesser extent, SIRT3 (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3A). Interestingly, K-RAS was not able to interact with a catalytically dead form of SIRT2 (Fig. S3B). Similar to knockdown or inhibition of HDAC6, and consistent with the effect of NAM, knockdown of SIRT2 increased the levels of acetylated RAS in CRC cells (Fig. 2B). These data suggest that HDAC6 and SIRT2 both regulate RAS acetylation state. By extension, we expected SIRT2 knockdown to have a similar effect as HDAC6 knockdown in cells expressing mutant forms of K-RAS. Indeed, K-RAS mutant CRC cells were sensitive to SIRT2 knockdown in both short-term and long-term assays of transformation (Fig. 2C–E and Fig. S3C). We also found that some K-RAS mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells were sensitive to loss of SIRT2 (Fig. S3D). Altogether, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that HDAC6 and SIRT2, either independently or cooperatively, modulate K-RAS acetylation and, therefore, its oncogenic properties.

Figure 2.

SIRT2 regulates K-RAS acetylation and oncogenicity. A, SIRT2 interacts with K-RAS. Ectopic K-RAS could be detected by western blot after immunoprecipitation of ectopic SIRT2 with anti-FLAG antibody in 293T cells. Ectopic SIRT3 could also interact with K-RAS, although to a lesser extent. In this experiment, 293T cells were transiently transfected with CMV-FLAG vector individually expressing one of the seven Sirtuins (T1-T7), or else empty FLAG vector (V). All of the cells were also transfected with plasmid expressing HA-tagged K-RASG12V. B, Effect of SIRT2 knockdown on RAS acetylation. Acute knockdown of SIRT2 led to a significant increase in acetylated RAS. C, Effect of SIRT2 knockdown on viability. Acute knockdown of SIRT2 significantly reduced viability of CRC cells in a short-term (3 days) assay. Knockdown of KRAS was used as a positive control. Data were normalized to cells treated with a non-targeted pool (NTP) siRNA. D, Effect of SIRT2 knockdown on clonogenic survival. Chronic SIRT2 knockdown, like KRAS knockdown, significantly affected colony formation in CRC cells. Cells infected with empty shRNA vector were used as a negative control. Data were normalized to cells infected with empty shRNA vector. E, Effect of SIRT2 knockdown on proliferation. The proliferation of CRC cells with stable SIRT2 or KRAS knockdown was reduced compared to cells infected with empty vector.

Among all of the Sirtuin family members, the interaction between K-RAS and SIRT2 makes the most sense, since SIRT2 is the only family member thought to be predominantly cytoplasmic (7). SIRT2, like HDAC6, is a tubulin deacetylase and these two enzymes are thought to be essential coenzymes (17, 18). Interestingly, SIRT2 was previously reported to act as a tumor suppressor gene in the mouse pancreas (19). Other studies link SIRT2 to the stabilization of the Myc oncoproteins by regulation of NEDD4, an E3 ubiquitin ligase (20). Our data are consistent with a direct oncogenic function for SIRT2, just like its coenzyme HDAC6. Since acetylation negatively regulates K-RAS, and SIRT2 and HDAC6 promote de-acetylation, these enzymes positively regulate K-RAS activity.

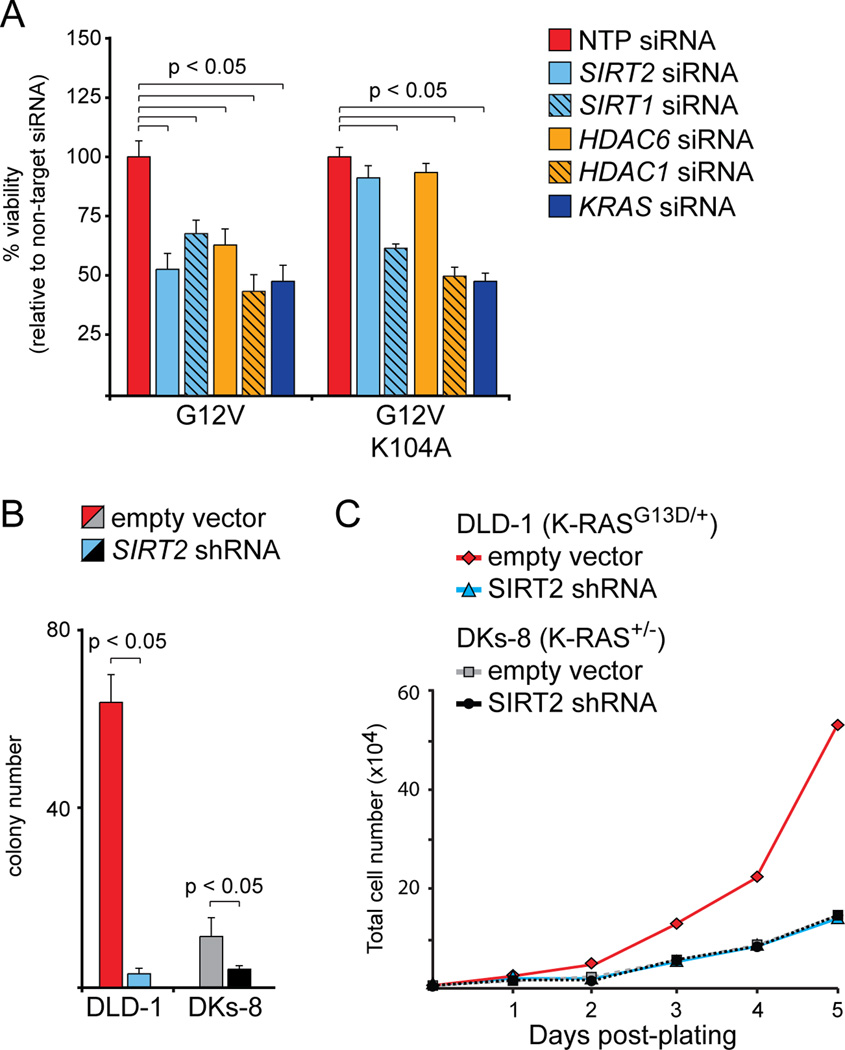

A major question that arises from our data is whether the anti-tumorigenic effects of HDAC6/SIRT2 are directly related to K-RAS acetylation. To address this question, we utilized NIH3t3 cells that were transformed with activated (G12V) K-RAS. We previously demonstrated that an acetylation mimetic mutation in K-RAS (G12V/K104Q) suppressed transformation in NIH3t3 cells, but that a mutation that prevents acetylation (G12V/K104A) had no effect (5). Here, we found that SIRT2 or HDAC6 knockdown reduced viability in NIH3t3 cells expressing K-RASG12V, but not in cells expressing K-RASG12V/K0104A (Fig. 3A). We also found that knockdown of SIRT1, another Sirtuin that plays a role in cancer, or HDAC1 affected viability in cells expressing either K-RASG12V or K-RASG12V/K0104A (Fig. 3A). These observations suggest that the deleterious effects of SIRT2 or HDAC6 knockdown, but not SIRT1 or HDAC1, are directly linked to K-RAS acetylation.

Figure 3.

Specificity of knockdown for deacetylates. A, Effect of SIRT2 or HDAC6 knockdown on viability. Acute knockdown of SIRT2 or HDAC6 significantly reduced viability of NIH3t3 cells expressing mutationally activated K-RAS (G12V), but only when amino acid 104 could be acetylated. Cells expressing K-RASG12V/K104A did not respond to knockdown of SIRT2 or HDAC6. Knockdown of KRAS was used as a positive control, as it reduces viability regardless of which amino acid is present at position 104. Knockdown of SIRT1 or HDAC1 also reduced viability under all circumstances, indicated that the deleterious effects of knockdown were not specific. All data were normalized to cells treated with a non-targeted pool (NTP) siRNA. B, Effect of SIRT2 knockdown on clonogenic survival. Chronic SIRT2 knockdown had a greater effect on colony formation in cells expressing mutant K-RAS (DLD-1) than in isogenic cells expressing wild-type K-RAS (DKs-8). Cells infected with empty shRNA vector were used as a negative control. Note that the K-RAS knockout in DKs-8 cells, like SIRT2 knockdown in DLD-1 cells, had a major effect on colony formation. C, Effect of SIRT2 knockdown on proliferation. The proliferation of K-RAS mutant DLD-1 cells was reduced by stable SIRT2 knockdown, but the proliferation of K-RAS wild-type DKs-8 cells was not. The proliferation rate of DLD-1 cells lacking SIRT2 was identical to that of DKs-8 cells (note that the curves are overlapping).

A second question is whether the effects of HDAC6/SIRT2 knockdown are specific to cells expressing mutant K-RAS. To address this question, we utilized an isogenic derivative of DLD-1 cells in which the mutant allele of K-RAS (G13D) has been removed via homologous recombination (21). When we performed SIRT2 knockdown in the K-RAS wild-type derivative (DKs-8), the effect on the colony forming phenotype was much less pronounced than in the parental DLD-1 cells (Fig. 3B). In a proliferation assay, SIRT2 knockdown had no detectable effect in DKs-8 cells, but essentially converted the growth rate of mutant cells to that of wild-type (Fig. 3C). Altogether, our results indicate that the deleterious effects of SIRT2 loss are specific to cells in which K-RAS is activated and can be acetylated.

KRAS activating mutations occur in approximately 40% of colon cancers, 90% of pancreatic cancers, and 30% of lung cancers, 3 of the 4 most deadly forms of cancer. Clearly, there is great need to develop new therapies to treat cancers expressing mutant K-RAS. Our observations suggest that targeting the post-translational modification of K-RAS protein, specifically its acetylation, may constitute a new therapeutic strategy. Strategies targeting other post-translational modifications of K-RAS have been largely ineffective in the past. For example, because K-RAS is modified by farnesyltransferase to promote its association with the plasma membrane, it was thought that inhibition of farnesyltransferase should prevent K-RAS from localizing to the cellular compartment from which it transmits its oncogenic signal (22). Farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs) ultimately failed in the clinic, however, because of gastrointestinal toxicity and because K-RAS is efficiently prenylated by geranylgeranyltransferase in the absence of farnesyltransferase activity (23). The identification of the enzymes that regulate K-RAS acetylation constitutes the first step toward a new therapeutic strategy targeting the post-translation modification of K-RAS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Research Scholar Grant to K.M.H. from the American Cancer Society (MGO-114877) and by a pilot project award from the Andrew L. Warshaw, M.D., Institute for Pancreatic Cancer Research at MGH. N.G is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. 1000087636. G.L is supported by a fellowship from Human Frontier Science Program. M.C.H was supported by Ellison Medical Foundation New Scholar Award, funding from NIA (R01AG032375), and the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Lau KS, Haigis KM. Non-redundancy within the RAS oncogene family: Insights into mutational disparities in cancer. Mol Cells. 2009;28:315–320. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janakiraman M, Vakiani E, Zeng Z, Pratilas CA, Taylor BS, Chitale D, et al. Genomic and biological characterization of exon 4 KRAS mutations in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5901–5911. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hancock JF, Magee AI, Childs JE, Marshall CJ. All ras proteins are polyisoprenylated but only some are palmitoylated. Cell. 1989;57:1167–1177. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasaki AT, Carracedo A, Locasale JW, Anastasiou D, Takeuchi K, Kahoud ER, et al. Ubiquitination of K-Ras enhances activation and facilitates binding to select downstream effectors. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra13. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang MH, Nickerson S, Kim ET, Liot C, Laurent G, Spang R, et al. Regulation of RAS oncogenicity by acetylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:10843–10848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201487109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.You L, Nie J, Sun WJ, Zheng ZQ, Yang XJ. Lysine acetylation: enzymes, bromodomains and links to different diseases. Essays Biochem. 2012;52:1–12. doi: 10.1042/bse0520001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haigis MC, Sinclair DA. Mammalian sirtuins: biological insights and disease relevance. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:253–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finley LW, Haas W, Desquiret-Dumas V, Wallace DC, Procaccio V, Gygi SP, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase is a direct target of sirtuin 3 deacetylase activity. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ventura A, Meissner A, Dillon CP, McManus M, Sharp PA, Van Parijs L, et al. Cre-lox-regulated conditional RNA interference from transgenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10380–10385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403954101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hubbert C, Guardiola A, Shao R, Kawaguchi Y, Ito A, Nixon A, et al. HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature. 2002;417:455–458. doi: 10.1038/417455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuyama A, Shimazu T, Sumida Y, Saito A, Yoshimatsu Y, Seigneurin-Berny D, et al. In vivo destabilization of dynamic microtubules by HDAC6-mediated deacetylation. EMBO J. 2002;21:6820–6831. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Li N, Caron C, Matthias G, Hess D, Khochbin S, et al. HDAC-6 interacts with and deacetylates tubulin and microtubules in vivo. The EMBO journal. 2003;22:1168–1179. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Shin D, Kwon SH. Histone deacetylase 6 plays a role as a distinct regulator of diverse cellular processes. Febs J. 2012;280:775–793. doi: 10.1111/febs.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu J, Coyne CB, Sarkar SN. PKC alpha regulates Sendai virus-mediated interferon induction through HDAC6 and beta-catenin. EMBO J. 2011;30:4838–4849. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saji S, Kawakami M, Hayashi S, Yoshida N, Hirose M, Horiguchi S, et al. Significance of HDAC6 regulation via estrogen signaling for cell motility and prognosis in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:4531–4539. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee YS, Lim KH, Guo X, Kawaguchi Y, Gao Y, Barrientos T, et al. The cytoplasmic deacetylase HDAC6 is required for efficient oncogenic tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7561–7569. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.North BJ, Marshall BL, Borra MT, Denu JM, Verdin E. The human Sir2 ortholog, SIRT2, is an NAD+-dependent tubulin deacetylase. Mol Cell. 2003;11:437–444. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nahhas F, Dryden SC, Abrams J, Tainsky MA. Mutations in SIRT2 deacetylase which regulate enzymatic activity but not its interaction with HDAC6 and tubulin. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;303:221–230. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim HS, Vassilopoulos A, Wang RH, Lahusen T, Xiao Z, Xu X, et al. SIRT2 maintains genome integrity and suppresses tumorigenesis through regulating APC/C activity. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu PY, Xu N, Malyukova A, Scarlett CJ, Sun YT, Zhang XD, et al. The histone deacetylase SIRT2 stabilizes Myc oncoproteins. Cell Death Differ. 2012;20:503–514. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirasawa S, Furuse M, Yokoyama N, Sasazuki T. Altered growth of human colon cancer cell lines disrupted at activated Ki-ras. Science. 1993;260:85–88. doi: 10.1126/science.8465203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casey PJ, Solski PA, Der CJ, Buss JE. p21ras is modified by a farnesyl isoprenoid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8323–8327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sebti SM, Hamilton AD. Farnesyltransferase and geranylgeranyltransferase I inhibitors in cancer therapy: important mechanistic and bench to bedside issues. Exp Opin Invest Drugs. 2000;9:2767–2782. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.12.2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.