Abstract

Adult male circumcision (AMC) reduces HIV transmission but uptake is limited in part by current surgical methods. We randomized HIV-uninfected men (n=138) to receive Shang ring (SR) or forceps-guided (FG) AMC from a locally-trained surgeon. In as-treated analyses, more SR procedures were completed within 10 minutes (79% vs 0%, p<0.01) and more subjects reported high satisfaction (77% vs 58%, p=0.03). Healing time and pain scores were similar, though minor complication rates were higher in SR subjects (56% vs 24%, p<0.01). SR circumcision is a rapid and acceptable method of AMC and should be further evaluated to increase uptake of AMC.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Uganda, sub-Saharan Africa, Adult Male Circumcision, HIV prevention, acceptability, feasibility

BACKGROUND

Adult male circumcision (AMC) can reduce the incidence of HIV transmission by 40-60% in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).1-4 The World Health Organisation and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS advocate AMC for the reduction of HIV transmission in heterosexual men in fourteen high prevalence countries in the region,5 and others have demonstrated that AMC programmes can be effectively delivered and cost-effective from a societal perspective.6,7

Despite these recommendations, AMC uptake varies greatly, but remains below target in most areas.8 Fear of pain, and misinterpretation of the effects of AMC can discourage men from presenting for the procedure.9,10 Furthermore, operative methods of AMC that require formal surgical training and can be time-consuming might limit uptake in low-income countries. It has been estimated that approximately 100 procedures are required to attain adequate training for safe and effective operative AMC.11

As such, the WHO has recommended development and testing of rapid, safe, and simple methods to facilitate broader implementation of AMC, with particular attention to usability by mid-level providers.12 The Shang Ring (SR) (Wuhu Santa Medical Devices Technology Co Ltd, China) aims to satisfy these criteria. Preliminary studies have shown it to be a feasible and acceptable method of AMC in SSA13. We performed a randomized controlled effectiveness study to compare the SR with forceps-guided (FG) AMC in a publicly funded regional referral hospital with a locally trained surgeon in Mbarara, western Uganda.

METHODS

Eligibility and randomisation

Adult male students attending Mbarara University (≥15 years) undergoing elective AMC were recruited from the surgical outpatient department of Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital, Uganda. Patient age, marital status, smoking history and motive to seek AMC were recorded for each participant. Exclusion criteria included: self-reported HIV infection, chronic paraphimosis, genital ulcers, penile carcinoma, filariasis, xerotica obliterans, balanitis, glans-prepuce adhesions, frenular scar tissue, or any urethral anatomical abnormality such as hypospadias or epispadias.

We performed unblinded, block randomization by study day. Consenting participants selected an opaque envelope from a box for randomization to SR or FG groups. All AMC procedures were performed by a locally-trained surgeon who had performed over 100 prior FG procedures but who had no prior experience with the SR procedure.

Interventions

A single study surgeon performed all procedures in the hospital operating theatres. All devices were purchased directly from the company, which provided no funding and had no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study. In both study groups, participants were cleaned with povidone iodine solution and draped in a sterile fashion. Local anaesthesia was administered to the dorsal penile nerve and penile ring blocks using 3mg/kg of 1% lidocaine. Six Shang ring sizes were available for the study (ring sizes C, D, E, F, G, K, diameters 26-34mm). The surgeon measured participants in the SR group to determine ring size. Patients for whom a suitable ring size was not available crossed over to the FG group, but remained in the SR group for intention to treat (ITT) analyses. An assistant measured operative time using a stopwatch. For the SR group, timing began as the ring began to be fitted, and ceased when the foreskin had been excised. For the FG group, timing began at the first incision and ceased when the final suture was completed. Patients were discharged on the day of procedure, provided with sterile gauze dressings, and informed to change them twice daily until the first follow-up appointment.

Assessments and outcomes of interest

The lead investigator performed unblinded post-operative assessments at one hour after the procedure, and on the 3rd, 7th, 14th and 21st post-operative days. Primary outcomes of interest were based on WHO guidelines and included procedure time, pain scores (using ten-point visual analogue scale), time to resumption of normal activity (defined as attendance at university classes), patient satisfaction taken at conclusion of follow-up (rated as ‘low’, ‘average’, ‘high’ or “very high” and dichotomized as low/average or high/very high for analyses) and time to complete healing, defined as complete circumferential approximation of the skin at the prior preputial site without edema, erythema, or scabbing. All patients in the SR group returned and had outcomes assessed until complete healing, whereas 16 of 65 (25%) of FG participants failed to return before full healing. Those in the FG group who did not return were considered healed on the day of their next scheduled follow-up appointment (i.e. a patient presenting for a day 3 visit but not for subsequent appointments was considered healed on study day 7). We considered a minor complication as one requiring assessment by a clinician, including any of: a) SR slippage; b) infection requiring antibiotics, or c) any persistent complication on day 14. We considered a major complication any requirement for repeat operative management, bleeding or infection requiring hospital admission, or scarring disfigurement. Missing outcome data for patients in the FG group who did not return were allocated as favorable for analysis of outcomes to bias estimates of a superiority of the SR towards the null. Thus, for patients in the FG group who did not return, we considered them to have high satisfaction and no minor or major complications.

Statistical Analyses

We measured incidence rates of all outcomes and estimated relative risk for the SR versus FG groups by fitting Poisson regression models with robust errors. All analyses were initially performed using ITT analysis, and were repeated with an as-treated analysis by reallocating the 7 participants who crossed into the FG group. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata Version 11 (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

We regarded patient satisfaction as the primary indicator of superiority between the two circumcision methods. In order to show an increase in high satisfaction between the two groups from 70 to 90% with a power of 80% and alpha of 0.05%, we required enrolment of 72 participants into each treatment group.

Ethical statement

The research proposal and informed consent process was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board Committee at Mbarara University of Science and Technology. Patients who presented for circumcision but who did not consent to participate in the trial were offered FG AMC. SR devices were supplied by an independent third-party with no affiliation to Wuhu Santa Medical Devices Technology Co Ltd, China, who had no involvement in the design, interpretation, or writing of this study. The study has been registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01757938).

RESULTS

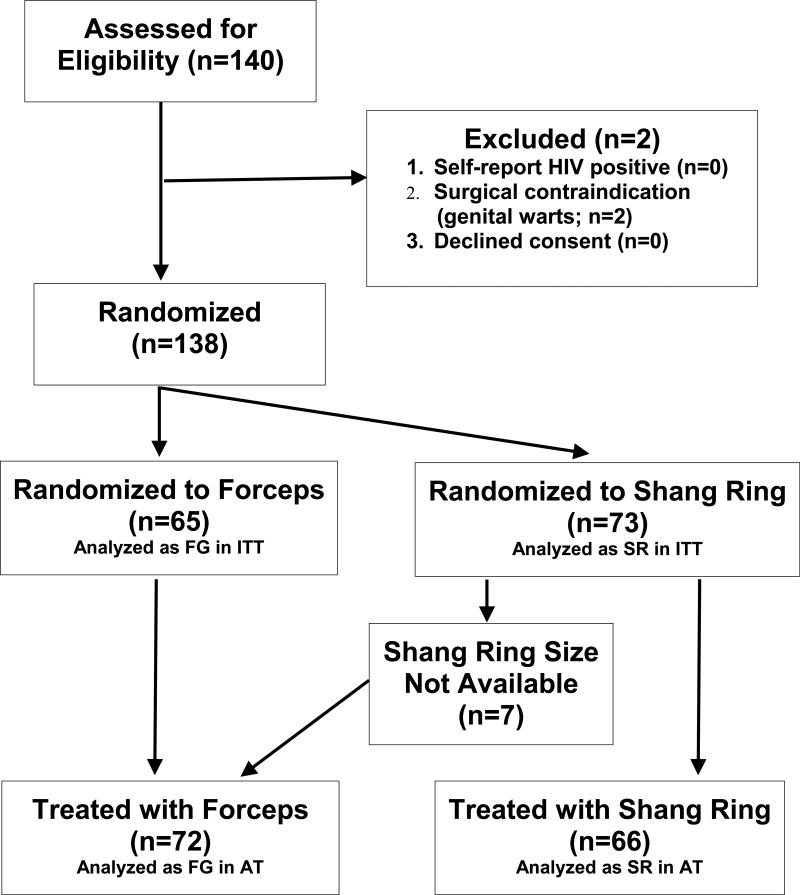

138 adult male students presenting to the surgical outpatient clinic requesting AMC between January - May 2011 and gave written informed consent (Figure 1). 73 and 65 patients were allocated to the SR and FG groups respectively. The median age was 22 years (interquartile range 21-23) and the majority of participants cited HIV prevention (55%) or general hygiene (41%) as their motive for seeking AMC.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant enrollment, randomization and analysis group.

Operative time was significantly shorter in the SR group, with 71.2% versus 0.0% of FG procedures complete within 10 minutes (p<0.001) and 95.6% versus 81.5% complete within 30 minutes (RR 1.18, 95%CI 1.04-1.33, p=0.01), (Table 1).

Table 1.

Outcomes for participants undergoing Shang Ring or Forceps-guided Adult Male Circumcision by both Intention to Treat and As-Treated Analyses

| Intention to Treat analysis | As Treated Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome (%) | Shang Ring (n=73) | Forceps (n=65) | RR (95%CI) | p-value | Shang Ring (n=66) | Forceps (n=72) | RR (95%CI) | p-value |

| Operative Time < 10 minutes | 71.2 | 0.0 | INF | -- | 78.8 | 0 | INF | -- |

| Operative Time < 30 minutes | 95.6 | 81.5 | 1.18 (1.04 - 1.33) | 0.01 | 97.0 | 81.9 | 1.18 (1.05 – 1.33) | 0.01 |

| Any Major Complication | 0.0 | 0.0 | -- | -- | 0.0 | 0.0 | -- | -- |

| Any Minor Complication | 57.5 | 18.5 | 3.12 (1.80 – 5.40) | <0.01 | 56.1 | 23.6 | 2.37 (1.49 – 3.79) | <0.01 |

| Ring Slippage | 5.5 | N/A | 6.1 | N/A | ||||

| Infection | 31.5 | 7.7 | 4.10 (1.64 - 10.1) | <0.01 | 27.3 | 13.9 | 1.96 (0.98 – 3.95) | 0.06 |

| Any Day 14 Complication | 42.5 | 16.9 | 2.51 (1.37 – 4.59) | <0.01 | 43.9 | 18.1 | 2.43 (1.38 – 4.28) | <0.01 |

| Healed by Day 7 | 12.3 | 13.9 | 0.89 (0.38 – 2.11) | 0.79 | 10.6 | 15.3 | 0.69 (0.29 – 1.69) | 0.42 |

| Healed by Day 14 | 34.3 | 50.8 | 0.67 (0.45 – 1.01) | 0.05 | 33.3 | 50.0 | 0.67 (0.44 – 1.01) | 0.06 |

| Healed by Day 21 | 90.9 | 95.4 | 0.95 (0.86 – 1.04) | 0.26 | 90.9 | 94.4 | 0.96 (0.88 -1.06) | 0.43 |

| Return to Activity Day 1 | 94.5 | 50.8 | 1.86 (1.45 – 2.38) | <0.01 | 95.4 | 54.2 | 1.76 (1.41 – 2.20) | <0.01 |

| Pain Free Post-Op Day 1 | 24.7 | 16.9 | 1.46 (0.74 – 2.86) | 0.27 | 27.3 | 15.3 | 1.79 (0.91 – 3.50) | 0.09 |

| Pain Free Post-Op Day 3 | 69.9 | 62.7 | 1.11 (0.87 – 1.43) | 0.50 | 71.2 | 62.1 | 1.15 (0.90 – 1.46) | 0.27 |

| Pain Free Post-Op Day 7 | 100 | 100 | -- | -- | 100 | 100 | -- | -- |

| High Patient Satisfaction | 74.0 | 60.0 | 1.38 (0.94 – 2.02) | 0.10 | 77.3 | 58.3 | 1.65 (1.04 – 2.60) | 0.03 |

Pain scores on the day of procedure were slightly higher in the FG group (median 3/10 [IQR 2-5]) than the SR group (median 1/10 [IQR 0-4], p=0.01 for difference). There were no significant differences in pain scores between the two groups at later time points, with 69.9% of SR patients versus 62.7% of FG patients pain free within 3 days (RR 1.11, 95%CI 0.87-1.43, p=0.50). All patients in both groups were pain free by the 7th post-operative day. 74.0% of patients in the SR group reported that they were highly satisfied with their procedure, compared to 60.0% of patients in the FG group, but this was not statistically significant (RR 1.38, 95%CI 0.94-2.02, p=0.10).

No participants in either group suffered a major complication (repeat operative procedure, infection or bleeding requiring admission, or scarring disfigurement). The rate of minor complications was higher in the SR (57%) group than the forceps-guided group (18%, RR 3.11, 95%CI 1.80 – 5.40), p<0.01). In the SR group, minor complications included slippage (6%), infection (32%), and any 14-day complication (43%: persistent wound [30%], infection [4%], minor bleeding [4%], suture discomfort [3%], edema [1%]). In the FG group, minor complications were infection (8%) and any 14-day complication (17%: persistent wound [8%], suture discomfort [6%], infection [3%]). All infections resolved with use of oral antibiotics. Urinary retention or difficulty in passing urine was reported by 2 (3%) FG and 3 (4%) SR patients on day 3, but none sought medical assistance at the time. One participant in the SR group was noted to have significant penile sedema at the day 14 assessment, but this was successfully managed conservatively.

Time to complete healing was similar in the SR (median 14 days [IQR 8 – 18]) and FG groups (median 13 days [IQR 8 – 14]), with 12.3 vs. 13.9%, 34.3 vs. 50.8% and 90.9 vs 95.4% fully healed by days 7, 14 and 21 days respectively. There was no significant difference in time to healing by log-rank testing (p=0.08). Time to resumption of normal activity was significantly faster in the SR group, with 94.5% able to attend classes on the first post-operative day, compared to 50.8% of forceps-guided patients (RR 1.86, 95%CI 1.45-2.38, p<0.01).

Seven participants randomized to SR underwent FG AMC because of unavailability in ring size (all required the larger ring sizes [size A=36mm]). In as-treated analyses, 66 patients received SR and 72 underwent FG-guided adult male circumcision. In this analysis, the difference in the overall rate of complications remained statistically significant (56.1% Shang Ring versus 23.6% forceps-guided, RR 2.37, 95%CI 1.49-3.79, p<0.01). The proportion of satisfied patients was significantly higher in the SR (77.3%) versus FG groups (58.3%) (RR 1.65, 95%CI 1.04-2.60, p=0.03). No other differences between the two groups significantly changed with this analysis.

DISCUSSION

At a regional hospital in provincial Uganda, we found that SR-guided AMC was relatively rapid, enabled earlier return to normal activity and produced similar patient satisfaction when compared to FG-guided AMC. However, we also found post-operative complications, and especially uncomplicated ring-site infections, were significantly higher with the SR-procedure. Importantly, our data are reflective of procedures performed by a local staff in a prototypical, publicly funded referral hospital in southwestern Uganda, and thus an indication of the effectiveness of the device in settings where it might be of highest impact.

Our results corroborate those of other studies that have shown alternative methods of AMC to be a more timely procedure than standard surgical techniques previously advocated by the WHO.14-16 The relatively rapid procedure time along with its potential use by non-operatively trained health professionals make it a potentially attractive option in high-demand communities with hyperendemic HIV prevalence and/or a shortage of professionally trained health care workers. Future evaluations of its use by non-physicians will elucidate its role further in these settings.

Higher levels of patient satisfaction and early return to normal activities with the Shang Ring suggest that it has the capacity to increase uptake in areas with low rates of AMC7. Though previous studies have suggested that fear of pain associated with the procedure are partially responsible for poor uptake,9,10 we found that pain was modest with the SR procedure and completely resolved by day 7 in all participants. Median time to healing in our study (median 14 days) was somewhat faster than that reported elsewhere (median 20 days), though this might be due to differences in definition of full healing.17 Moreover, faster time to return to normal activities would have importance both for patient preference and secondary considerations related to lost work and education.

Conversely, we found a potentially concerning increased rate of complications in those undergoing SR-AMC. This may reflect the operator's lack of experience with the device. Rates of complication may reduce over time as has been demonstrated in studies of traditional AMC, though this should be evaluated in future evaluations.10 Importantly, none of our recorded complications required further surgical intervention or inpatient admission. However, careful attention to short and long-term complications should be further considered as these findings will be essential for programmes considering implementation of the procedure in low-resource settings.

Our study was limited by availability of Shang Ring sizes. We did not have the largest ring size (size A, 36mm), which was required for seven eligible participants randomized to the SR. Though results did not differ greatly in the as-treated analysis, this shortcoming served to highlight that a wide range of ring sizes must be available for an effective AMC service to be provided using this method. The study population was largely composed of young (median age 22), relatively healthy university students and thus might not reflect the expected operative outcomes of older populations or those with co-morbidities. Our results highlight the need for further studies to undertake large-scale, randomised controlled trials to compare Shang Ring with other rapid, simple AMC methods and traditional surgical AMC. Because of the large need and known limitations with current methods, a widely accepted, safe, and simple procedure performed by non-surgeon health care workers would allow broad adoption of AMC in SSA, where both its impact and barriers to use are greatest.

In summary, we demonstrate that the SR AMC device is a rapid, simple method of AMC that might serve as an effective method of increasing the uptake and acceptability in resource-limited settings. Further studies to validate our findings and investigate both short and long-term complication rates with repeated use should be pursued.

Acknowledgments

Support:

MJS received salary support from the Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program at Vanderbilt University (R24 TW007988), and the NIH (T32 AI007433).

Footnotes

Disclosures:

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005 Nov;2(11):e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007 Feb 24;369(9562):643–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007 Feb 24;369(9562):657–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J. Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD003362. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO/UNAIDS [3/16/2013];Joint Strategic Action Framework to Accelerate the Scale-Up of Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention in Eastern and Southern Africa. 2011 Nov; http://whqlibdoc.who.int/unaids/2011/JC2251E_eng.pdf.

- 6.Lissouba P, Taljaard D, Rech D, et al. A model for the roll-out of comprehensive adult male circumcision services in African low-income settings of high HIV incidence: the ANRS 12126 Bophelo Pele Project. PLoS Med. 2010 Jul;7(7):e1000309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Njeuhmeli E, Forsythe S, Reed J, et al. Voluntary medical male circumcision: modeling the impact and cost of expanding male circumcision for HIV prevention in eastern and southern Africa. PLoS Med. 2011 Nov;8(11):e1001132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) AIDS at 30: nations at a crossroads. UNAIDS; Geneva: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gasasira RA, Sarker M, Tsague L, et al. Determinants of circumcision and willingness to be circumcised by Rwandan men, 2010. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lissouba P, Taljaard D, Rech D, et al. Adult male circumcision as an intervention against HIV: an operational study of uptake in a South African community (ANRS 12126). BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:253. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiggundu V, Watya S, Kigozi G, et al. The number of procedures required to achieve optimal competency with male circumcision: findings from a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. BJU Int. 2009 Aug;104(4):529–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. [3/16/2013];WHO Framework for Cinical Evaluation of Devices for Male Circumcision. 2012 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75954/1/9789241504355_eng.pdf.

- 13.Barone MA, Ndede F, Li PS, Masson P, Awori Q, Okech J, et al. The Shang Ring device for adult male circumcision: a proof of concept study in Kenya. Journal of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. 2011;57(1) doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182158967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li HN, Xu J, Qu LM. [Shang Ring circumcision versus conventional surgical procedures: comparison of clinical effectiveness]. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2010 Apr;16(4):325–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mutabazi V, Kaplan SA, Rwamasirabo E, et al. HIV prevention: male circumcision comparison between a nonsurgical device to a surgical technique in resource-limited settings: a prospective, randomized, nonmasked trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Sep 1;61(1):49–55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182631d69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Decastro B, Gurski J, Peterson A. Adult template circumcision: a prospective, randomized, patient-blinded, comparative study evaluating the safety and efficacy of a novel circumcision device. Urology. 2010 Oct;76(4):810–814. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng Y, Peng YF, Liu YD, et al. [A recommendable standard protocol of adult male circumcision with the Chinese Shang Ring: outcomes of 328 cases in China]. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2009 Jul;15(7):584–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]