Abstract

Background

Although the etiology of two major forms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are unknown and evidence suggests that chronic intestinal inflammation is caused by an excessive immune response to mucosal antigens. Previous studies support the role for TGF-β1 through 3 in the initiation and maintenance of tolerance via the induction of regulatory T cells (Tregs) to control intestinal inflammation. Leptin, a satiety hormone produced primarily by adipose tissue, has been shown to increase during colitis progression and is believed to contribute to disease genesis and/or progression.

Aim

We investigated the ability of a pegylated leptin antagonist (PG-MLA) to ameliorate the development of chronic experimental colitis.

Results

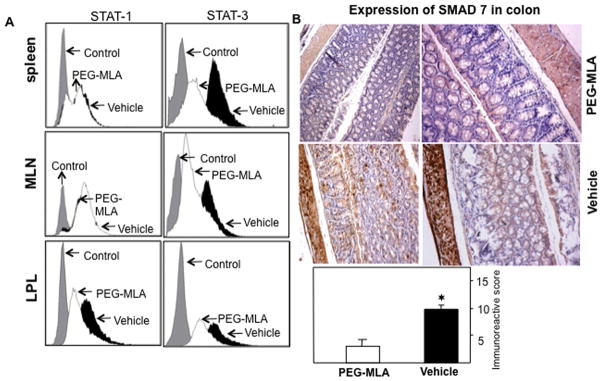

Compared to vehicle control animals, PG-MLA treatment of mice resulted in an (1) attenuated clinical score; (2) reversed colitis-associated pathogenesis including a decrease in body weight; (3) reduced systemic and mucosal inflammatory cytokine expression; (4) increased insulin levels and (5) enhanced systemic and mucosal Tregs and CD39+ Tregs in mice with chronic colitis. The percentage of systemic and mucosal TGF-β1, -β2 and -β3 expressing CD4+ T cells were augmented after PG-MLA treatment. The activation of STAT1 and STAT3 and the expression of Smad7 were also reduced after PG-MLA treatment in the colitic mice. These findings clearly suggest that PG-MLA treatment reduces intestinal Smad7 expression, restores TGF-β1-3 signaling and reduces STAT1/STAT3 activation that may increase the number of Tregs to ameliorate chronic colitis.

Conclusion

This study clearly links inflammation with the metabolic hormone leptin suggesting that nutritional status influences immune tolerance through the induction of functional Tregs. Inhibiting leptin activity through PG-MLA might provide a new and novel therapeutic strategy for the treatment of IBD.

Keywords: Inflammation, Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), Leptin, Antagonist, Pegylated, Ulcerative Colitis (UC), Crohn’s Disease (CD)

Introduction

It is generally agreed that inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a multifactorial disease state with immunological, environmental and genetic influences. IBD, especially Crohn’s disease (CD), is commonly characterized by weight loss, anorexia and increased energy expenditure during the acute stages of intestinal inflammation (Silk and Payne-James, 1989; Rigaud et al., 1994; De Gaetano et al., 1996; Ehrhardt et al., 1997). While the causes of IBD remain unknown, the disease has been associated with food intake, increased energy expenditure and a reduced absorption of nutrients (Greenberg et al., 1989). Recently, it was suggested that the anorexigenic hormone leptin, might play a role in the anorexia associated with chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer. Anorexia, malnutrition and altered body composition are well-established features associated with IBD.

Leptin is a hormone produced primarily by adipose tissue (Auwerx and Staels, 1998) with a primary function of controlling appetite and adiposity. Leptin has recently been shown to play a role in the control of inflammation and autoimmunity (De Rosa et al., 2006) and emerged as a potential inducer of inflammatory cytokine expression, more specifically IL-1, TNF-α, and IL-6 (Grunfeld et al., 1996; Dixit et al., 2004). In humans, increases in leptin levels are associated with ulcerative colitis (Tuzun et al., 2004; Karmiris et al., 2006) and over-expression of leptin mRNA in mesenteric adipose tissue in IBD patients has been reported (Barbier et al., 2003). Colonic leptin induces epithelial wall damage and neutrophil infiltration, a typical characteristic of histological findings in acute intestinal inflammation (Sitaraman et al., 2004). Similarly, in rat s, elevated plasma leptin concentrations correlates with an increase in intestinal inflammation (Barbier et al., 1998).

Despite strong evidence supporting a role for leptin in inflammation and autoimmunity, the precise mechanism of its action has been controversial and both direct and indirect mechanisms have been described (Lord et al., 1998; Palmer et al., 2006). Leptin can directly affect numerous immune cell types of both the innate and adaptive immune systems and can induce pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (Fernandez-Riejos et al., 2010). In a recent study, a direct link of leptin with Tregs anergy and hyporesponsiveness was described (De Rosa et al., 2007). Interestingly, an important source of leptin is Tregs themselves, which appear to express both leptin and its receptors (De Rosa et al., 2007). Mice with a genetic deficiency in leptin have a higher percentage and absolute number of circulating Tregs (Hasenkrug, 2007) and the treatment of wild type mice with leptin neutralizing antibody produces an expansion of Tregs. In a recent study by Matarese and colleagues (Matarese et al., 2005b), an increase in leptin in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients correlated with a reduced number of regulatory T cells (Matarese et al., 2005a). These reductions in Tregs levels are likely a direct consequence of leptin binding to receptors of regulatory cells.

TGF-β signaling in Tregs is essential to efficiently control inflammation in the colon (Huber et al., 2004). Oral administration of haptenized colonic proteins protects mice from the induction of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) colitis by the generation of mucosal T cells that produce TGF-β (Neurath et al., 1996; Fuss et al., 2002). TGF-β either directly down-regulates the differentiation and function of effector T cells or induces the expression of forkhead transcription factor (FoxP3) expression associated with Tregs (Chen et al., 2003; Fantini et al., 2004; Rao et al., 2005). TGF-β1 signaling occurs from receptors to the nucleus via a set of proteins termed Smads. The up-regulation of inhibitory Smad7 is associated with inhibition of TGF-β1-induced Smad signaling (Nakao et al., 1997). It has been shown that activators of either NF-κB or signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-1 pathways can enhance Smad7 expression (Ulloa et al., 1999). The activation of STAT-1/STAT-3 pathways is well documented in playing an important role in both human IBD and experimental colitis (Suzuki et al., 2001; Schreiber et al., 2002; Lovato et al., 2003). Furthermore, oral administration of Smad7 antisense oligonucleotide reduced systemic Smad7 expression and restored TGF-β1 associated P-Smad3 expression in colons of mice in TNBS and oxazolone-induced models of colitis(Monteleone et al., 2012).

In the present study, we investigated whether the blockade of leptin by PG-MLA mediates the development and progression of chronic colitis in IL10−/− mice. We have studied the cellular and molecular mechanism of PG-MLA treatment mediated abrogation of colitis. The results from this study clearly suggest that PG-MLA increases systemic and mucosal Tregs through restoration of TGF-β1-3 signaling, supported in part by a decrease in Smad7 expression, STAT1/3 activation that leads to reduced inflammatory cytokine levels, histological scores, and severity of disease to abrogate chronic colitis.

Materials and Methods

Human Sera, and Tissue Collection

Blood from a total of 120 age-matched untreated IBD patients and 30 healthy donors (30 each from African American, European, Ashkenazi Jewish, Asian American), and colon tissue from 8 patients, two from each ethnic group and two from normal healthy donors were collected (Clinomics Biosciences, Inc.; Pittsfield, MA). After providing information on the future use of serum in biomarker analysis, formal consent was obtained from all patients approved by the Clinomics Biosciences Research Ethics Committee. These patients did not receive any steroid treatments before blood was taken. Age, gender, and race/ethnic/geographic origin were considered. Average mean age was 47 and ranged from 40 to 71 years. Studies included enough serum/plasma samples from these groups to ascertain statistically significant differences. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate and compared with a standard curve using ELISA techniques to measure leptin concentrations.

Animals

Female IL-10−/− mice on the C57BL/6 background aged 8 to 12 weeks were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Under standard laboratory conditions, IL-10−/− mice develop spontaneous colitis at 12 weeks of age. Animals were housed and maintained in isolator cages under normal light and dark cycles in conventional housing conditions to minimize animal pain and distress in the University of South Carolina School of Medicine animal facility Columbia, USA. Experimental groups consisted of 6 mice and studies were repeated 3 times. The body weights of mice were monitored twice on each Monday and Thursday in a week. Even though it has been reported that IL-10−/− mice develop colitis at age of 12 weeks under conventional housing conditions, we did not notice a major weight change until the onset of severe chronic colitis.

PG-MLA and leptin Antagonist treatment

Mouse leptin antagonist (mutant L39A/D40A/F41A) and PG-MLA was purchased from Protein Laboratories Rehovot LTD (Tel Aviv, Israel). The mutant leptin was purified by proprietary chromatographic techniques and was greater than 98% pure determined by gel filtration analysis. The endotoxin levels of this mutant are found to be less than 0.05ng/μg (0.5 EU/μg). The biopotency of leptin antagonist is increased by attaching it to polyethylene glycol (PEG) molecules resulting in reduced renal clearance and consequent prolongation of its half life cycle. Based on previous studies from our laboratory (Singh et al., 2003), serum amyloid A (SAA) and -IL-6 levels generally peaked during the 18th week, corresponding with the onset of chronic colitis. At this stage, mice received 200 μl by intraperitoneal injection of vehicle, MLA and PG-MLA (6.25 mg/kg body weight) twice a week on each Monday and Thursday till week 27 at the end-point of the experiment. At the experimental end-point, blood was collected by tail-vein bleedings and serum was obtained following centrifugation. For comparison, a similar treatment was also given to normal BL/6 mice.

Cytokine quantitation by Luminex™ analysis

At the experimental end point, level of IL-6, TNF-α, monocyte chemotactic protein1 (CCL2), lipopolysaccharide-induced CXC chemokine (CXCL5), insulin and resistin in the serum were determined by a Luminex Elisa assay kit as described by manufacturer protocol (Millipore Corporation, MA USA). Briefly, IL-6, TNF-α, CCL2, CXCL5, insulin and resistin analyte beads in assay buffer were added into pre-wet vacuum wells followed by 25 μl of serum or standard solution, 25 μl of assay buffer, and 25 μl of assay beads, and incubated overnight at 4°C with continuous shaking (at setting #3) using a Lab-Line™ Instrument Titer Plate Shaker (Melrose, IL). The filter bottom plates were washed and vortexed at 300× g for 30 seconds. Subsequently, 25 μl of anti-mouse detection Abs were added to each well and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Next, 25 μl of streptavidin-phycoerythrin solution was added and incubated with continuous shaking for 30 minute at RT. 200 μl of wash buffer was added and Milliplex™ readings were measured using a Luminex™ System (Austin, TX) and calculated using Millipore software. The Abs Milliplex™ MAP assays were capable of detecting >10 pg/ml for each analyte.

Acute phase serum amyloid A (SAA) ELISA

SAA level in the serum was essentially performed by an ELISA kit according to Biosource International (Camarillo, CA) protocol. In brief, 50 μl of SAA-specific monoclonal Abs solution were used to coat micro-titer strips to capture SAA. Serum samples and standards were added to wells and incubated for 2 hours at RT. After washing in the assay buffer, the HRP-conjugated anti-SAA monoclonal Abs solution was added and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. After washing, 100μl TMB substrate solution was added and the reaction was stopped after incubation for 15 minutes at RT. The plates were read at 450nm after the addition of stop solution.

Serum leptin ELISA

Serum leptin levels were measured by means of ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Crystal Chemical INC., Chicago, IL). Briefly, after washing each well with 300 μl of washing buffer, in each well 5μl of serum sample, 50μl of guinea pig anti-mouse leptin serum and 45 μl of sample diluents were added. After the serum samples, standards were added to wells, micro-plate covered and incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing in the assay buffer, 100μl of anti-guinea pig IgG enzyme conjugate were added and incubated for 3 hour at 4°C. After washing with buffer, 100μl of enzyme substrate were added and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. The reaction was stopped after 30 minutes incubation at room temperature by adding100μl of enzyme reaction stopping solution. After the stop solution was added, the plates were read at 450nm.

Cell isolation

Spleens and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) from individual mice were mechanically dissociated and RBC’s lysed with lysis buffer (Sigma St. Louis, MO). Single cell suspensions of spleen and MLN were passed through a sterile wire screen (Sigma St. Louis, MO). Cell suspensions were washed twice in RPMI 1640 (Sigma) and stored in media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) on ice until used after one to two hours. The small intestine/colon was cut into 1-cm strips and stirred in PBS containing 1mM EDTA at 37 °C for 30 min. Cells from the intestinal lamina propria (LP) were isolated as described previously (Singh et al., 2003). In brief, the LP was isolated by digesting intestinal tissue with collagenase type IV (Sigma) in RPMI 1640 (collagenase solution) for 45 min at 37°C with moderate stirring. After each 45 min interval, the released cells were centrifuged and stored in complete media. Mucosal pieces were again treated with fresh collagenase solution for at least two times and cells were pooled. LP cells were further purified using a discontinuous Percoll (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) gradient collecting at the 40–75% interface. Lymphocytes were maintained in complete medium, which consisted of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 ml/L of nonessential amino acids (Mediatech, Washington, DC), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma), 10 mM HEPES (Mediatech), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 40 μg/ml gentamycin (Elkins-Sinn, Inc., Cherry Hill, NJ), 50 μM mercaptoethanol (Sigma) and 10 % FCS (Atlanta Biologicals).

Flow cytometry analysis

Cells from the spleen, MLN, and LP were freshly isolated from each mouse as described above for each experimental group and pooled together. For three to four color FACS cell surface antigen staining, cells were pre-blocked with Fc receptors for 15 min at 4°C. The cells were washed with FACS staining buffer (PBS with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and then stained with concentrations suggested by the manufacturers of FITC- or PE-conjugated anti-CD4 (H129.19), - FoxP3- (BD-PharMingen, San Diego CA), and PE conjugated anti-TGF-β1-3 monoclonal antibody (R&D System Inc. Minneapolis, MN), PE conjugated anti-mouse CD39 (Bio-Legend, Inc.) for 30 minutes with occasional shaking at 4°C. The cells were washed two times with FACS staining buffer and thoroughly re-suspend in BD Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD-PharMingen, San Diego CA) solution for 20 min. The cells were again washed two times with BD perm/wash solution after keeping it 10 min at 4°C. The TGF-β1-3 staining was performed according to instruction by the (R&D System Inc.). Cells were then washed thoroughly with FACS staining buffer and analyzed by flow cytometry (FC 500 by Beckman Coulter Fort Collins CO).

Analysis of STAT1 and STAT3 expression

At the experimental end point, cells from the spleen, MLN and LP were isolated as described above for each experimental group. The cells were fixed (BD cytofix/cytoperm TM) for 10 minutes at 37°C and permeabilized on ice for 30 minutes. The cells were then stained with Alexa Flour 647 mouse anti-STAT1 (pS727) Abs, (BD-PharMingen, San Diego CA). The cells were washed with FACS staining buffer (PBS with 1% FBS), and analyzed by flow cytometry (FC 500 by Beckman Coulter Fort Collins Co). For STAT3 staining, we used PE conjugated Phospho-stat3 (Tyr705) (DA37) Rabbit mAb (clone #8119; Cell Signaling Technology). In brief, the spleen cells were fixed in 2% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at 37°C, and permeabilized with 100% methanol for 30 minutes on ice. After washing with incubation buffer (PBS with 2% FBS), PE conjugated STAT3 Abs were added and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing with incubation buffer, cells were re-suspended in 0.5 ml of PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry.

PG-MLA enhances frequency of Tregs through TGF-βRIII signaling

Purified MLN T cells from normal C57Bl/6 (BL/6) mice were cultured at a density of 106 cells/ml in a complete medium containing 20 μg/ml of PG-MLA/MLA for two days with or without 20 ng/ml of recombinant mouse TGF-βRIII and TGF-βRI kinase inhibitors VI 10μM (A83-01; Calbichem, USA). CD3 (3 μg/ml) and CD28 (2 μg/ml) were used to activate the lymphocytes. After incubation for two days, the cells were stained with FITC- rat anti-mouse CD4 respective isotype controls (BD, PharMingen) for 30 min with shaking. The cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with PE- FoxP3 (BD, PharMingen) for 30 minutes. The cells were then washed with FACS buffer (PBS with 1% FBS) and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACS Aria II, Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA).

Immunohistochemical Staining

Sections of paraffin embedded colon tissue were incubated for immunohistochemical staining with antibodies against Smad7 (Mouse monoclonal clone #293039, 25 μg/ml, R&D systems). To ensure even staining and reproducible results, the sections were incubated overnight in primary antibodies (4° C). Following incubation with primary antibody, sections were processed using a rabbit ABC staining kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, INC). The chromogen was DAB and sections were counter-stained with hematoxylin. Stained tissues were examined for intensity of staining using a method similar to that previously described by our group (Cui et al., 2010). The two independent blind investigators from the study evaluated the staining intensity of the colon section. For each tissue section, the percentage of positive cells was scored on a scale of 0 to 4 for the percentage of tissue stained: 0 (0% positive cells), 1 (<10%), 2 (11% to 50%), 3 (51% to 80%), or 4 (> 80%). Staining intensity was scored on a scale of 0 to 3: 0-negative staining, 1-weak staining, 2-moderate staining, or 3-strong staining. The two scores were multiplied resulting in an immunoreactivity score (IRS) value range from 0 to 12.

Histology

Colons were preserved using 10% buffer neutral formalin followed by 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Fixed tissues were sectioned at 6 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for microscopy examination. Intestinal lesions were multi-focal and of variable severity. Grades were given to intestinal sections that took into account the number of lesions as well as severity. A score (0 to 4) was given based on established criteria (Singh et al., 2003).

Statistics

The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and compared using a two-tailed student’s t-test or an unpaired Mann Whitney U test. The results were analyzed using the Statview II statistical program (Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, CA) for Macintosh computers and were considered statistically significant if p values were less than 0.05.

Results

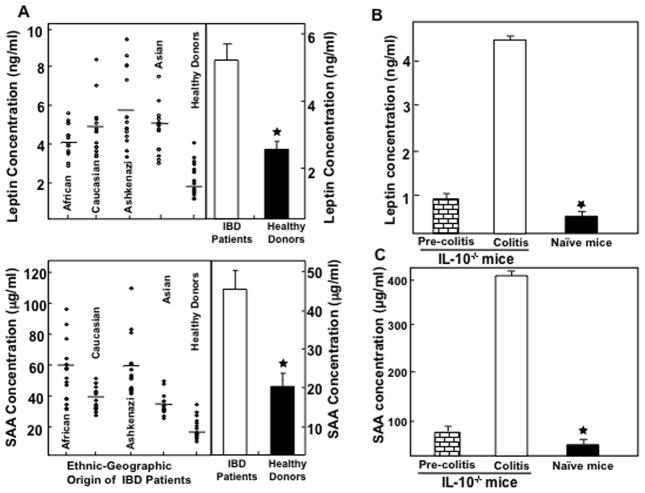

Serum leptin and SAA levels are elevated during IBD and experimental colitis

Previous studies have shown that elevated serum SAA and leptin levels correlate with the severity of IBD (Berg et al., 1996; Tuzun et al., 2004). The serum leptin and SAA levels in IBD patients were significantly higher than they were in normal, healthy donors (Fig. 1A, right panel). We next examined the sera derived from various ethnic groups (African American, European, Ashkenazi Jewish, and Asian American) of IBD patients and normal healthy donors not undergoing any treatment for biologics and immunosuppressive drugs. Normal healthy donors demonstrated significantly lower levels of serum leptin and SAA when compared to IBD patients of different ethnic groups (Fig. 1A, left panel). When we compared levels within ethnic groups, Ashkenazi Jews and Caucasians revealed higher levels of leptin and SAA protein in their sera compared to other ethnic groups and healthy donors. These results strongly suggest that leptin and SAA levels correlate with severity of IBD and also have associations with patient ethnicity.

Fig. 1.

Serum leptin and serum amyloid A (SAA) levels in IBD patients and experimental colitis. Leptin and SAA levels in the serum of 120 IBD patients and 30 normal healthy donors, not undergoing any treatment were measured by ELISA assays capable of detecting >10 pg/ml of leptin and SAA (panel A). The serum leptin and SAA in experimental colitis were measured at the experimental end point and in similar mice without colitis and naïve BL/6 mice (Panel B and C) by ELISA analysis. The statistical significance between values of each group was assessed using student’s t test. Data represent the mean concentration of three independent experiments involving six mice per group ± SEM and median values are shown. Asterisk(s) indicate statistically significant differences, i.e., p < 0.01 (★) between healthy donors vs. IBD patients and colitis mice with naïve and/or pre-colitis mice.

Next, we examined whether increased leptin in IBD patients could be reproduced in murine experimental models of colitis. The data revealed that serum leptin levels increased continuously within pre-colitic mice to reach a peak during chronic colitis as compared to normal BL/6 mice (1 B). Interestingly, these increases in leptin levels also correlate with the severity of inflammation as seen by an increase in infiltrating cells in the colon. Similar to IBD patients, mice with chronic colitis also demonstrated an increase in SAA levels when compared to pre-colitis as well as naïve BL/6 (Fig. 1C). These data demonstrate increased systemic leptin and SAA levels in IL-10−/− mice during chronic colitis and these increases correlate with disease severity similar to the data observed in human IBD patients.

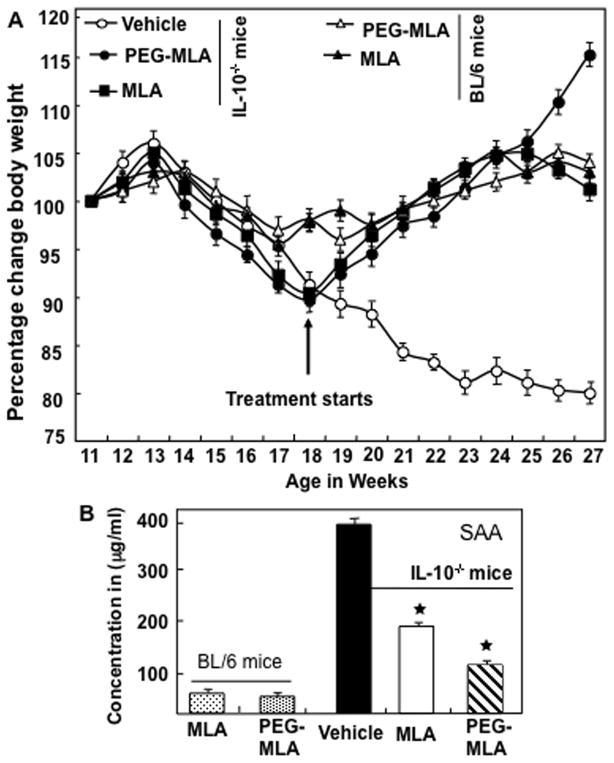

PG-MLA treatment prevents weight loss and SAA associated with colitis

Based on increases in leptin levels in the murine colitis model and in IBD patients, we sought to examine how antagonizing the activity of leptin may influence disease progression and development. To this end, we examined the effects of both PG and non-pegylated MLA on body weight and SAA concentration in IL-10−/− and normal BL/6 mice. No significant changes were observed in control BL/6 mice treated with PG-MLA and non PG-MLA throughout the study when compared to colitic mice. The PG-MLA shows effective results as compared to non-PG-MLA, therefore we used only PG-MLA in the rest of the study. When we compared the results of IL-10−/− control (vehicle) vs. PG-MLA-treated mice, we found that the vehicle-treated IL-10−/− mice developed chronic colitis (as shown by loss of 15–20% of body weight and occasional rectal bleeding). The body weight of the vehicle-treated mice continued to decline throughout the study (Fig. 2A). In contrast, PG-MLA treatment resulted in a significant increase in the body weight of IL-10−/− mice when compared to similar mice treated with vehicle (Fig. 2A). Previous results from our laboratory have shown that SAA levels serve as an indicator of colitis progression (Singh et al., 2003). SAA concentrations in the vehicle treated IL-10−/− mice were elevated significantly as compared with the PG-MLA treated mice (Fig. 2B). Together, these results suggest that PG-MLA is able to protect mice from colitis-induced weight loss and increases in SAA levels in IL-10−/− mice.

Fig. 2.

PG-MLA treatment mediates body weight and SAA concentrations during experimental colitis. IL-10−/− mice, on a BL/6 background, received 100 μl of vehicle (○), MLA (■) or PG-MLA (●) (12.5 mg/kg body weight). Normal BL/6 mice also received leptin antagonist (▲) or pegylated leptin antagonist (△) twice a week starting at the beginning of week 18 (panel A) and attained a peak in SAA levels (panel B) until week 27. Mice were sacrificed soon after week 27. The body weight of the IL-10−/− and normal BL/6 mice was recorded twice every week. The change from initial body weight was expressed as a percentage change in body weight. The statistical significance (★) P<0.05 between values from PG-MLA Vs vehicle treated IL-10−/− mice was assessed using Student’s t-test. Data represent the mean of three independent experiments involving six mice per group ± SEM.

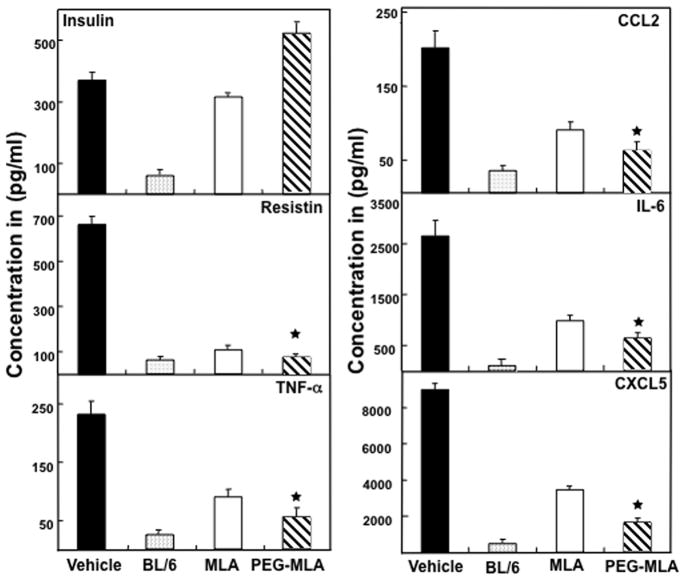

PG-MLA diminish elevated level of systemic adipocytes derived cytokines

Over production of TNF-α, IL-6, CCL2, and CXCL5 in inflammatory diseases including IBD and experimental colitis have been well documented (Powrie et al., 1994; Scheerens et al., 2001; Kwon et al., 2005). Adipose tissue-specific secretory factor (resistin ) has also been shown to be elevated in IBD patients (Konrad et al., 2007). Based on these, we next examined if PG-MLA treatment after chronic colitis could influence systemic levels of inflammatory and adipocyte-derived cytokines. We found that serum IL-6, TNFα, CCL2, CXCL5 and resistin levels increased after the onset of chronic colitis (Fig. 3), The mice that received PG-MLA demonstrated a significant (P <0.01) decline in all of these cytokines as compared to mice receiving vehicle alone (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, we noticed a further increase in serum insulin levels in the group of mice that received PG-MLA (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

PG-MLA reduces systemic resistin, CCL2, IL-6, CXCL5, and TNF-α levels. IL-10−/− mice with chronic colitis received a similar dose as described in Fig. 1. Following sacrifice, serum levels of insulin, resistin, CCL2, IL-6, CXCL5, and TNF-α were determined by Milliplex™-MAP ELISA kit that was capable of detecting >15 pg/ml of the above analytes. The data presented are the mean concentration of insulin, resistin, CCL2, IL-6, CXCL5, and TNF-α ± SEM of three separate experiments. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant differences (p< 0.01) between vehicle vs MLA and or PG-MLA treatment.

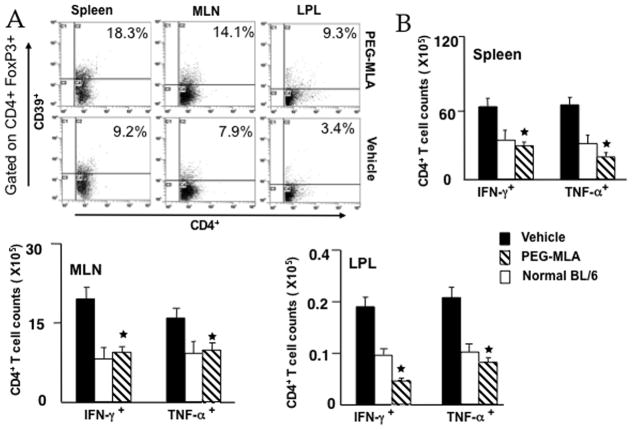

PG-MLA enhances the number of CD39+ cells and reduces mucosal cytokine expression in IL-10−/− colitic mice

CD39 was initially described as an activation marker for lymphoid cells and is expressed on virtually all CD4+Foxp3+cells (Borsellino et al., 2007). Upon PG-MLA treatment, the expression of both mucosal and systemic CD39+ FoxP3+ cells increased, when compared to vehicle treatment (Fig. 4A). PG-MLA also resulted in a significant decline in the expression of Th1 cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ and TNF-α) in colitic mice (Figure 4B). Enumeration of the number of IFN-γ- and TNF-α-expressing CD4+ T cells from spleen, MLN and LP lymphocytes of treated control versus colitic mice revealed a significant decline in the number of IFN-γ or TNF-α expressing CD4+ T cells in the spleen, MLN and LP of mice that received PG-MLA as compared with vehicle treated mice (Figure 4B right and lower panel). These data clearly indicate that PG-MLA treatment enhances the expression of ectonucleotidase CD39 on FoxP3+ Tregs and decreases the systemic and mucosal expression TNF-α, IFN-γ expressing CD4+ T cells in the MLN and effector LP in mice with colitis. Moreover, PG-MLA also restored the number of these Tregs to those found in naïve BL/6 mice.

Fig. 4.

PG-MLA mediates mucosal IFN-γ, TNF-α and CD39+ expressing Tregs. MLN, PP, and LP lymphocytes were isolated from IL-10−/− mice after similar doses as described in Fig. 2. Changes in the frequency of CD39 + and number of spleen, MLN and LP IFN-γ and TNF-α-expressing CD4+ T cells from vehicle as well as PG-MLA treated IL-10−/− mice are shown. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences, i.e., p < 0.01 (*), between vehicle and PG-MLA treated groups.

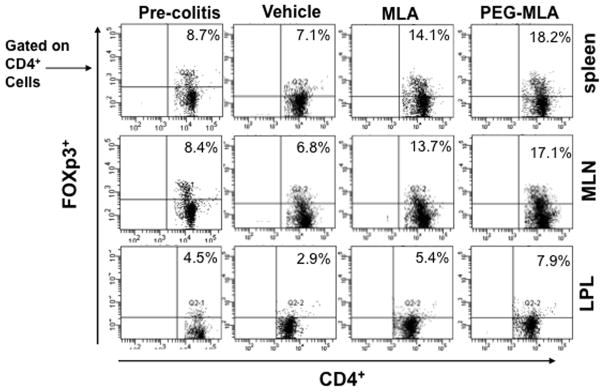

PG-MLA increases the Tregs frequency during colitis

It has been shown that a functionally specialized population of Tregs plays an important role in the control of intestinal inflammation (Coombes et al., 2005). Previous studies have shown that naturally arising Tregs cures colitis in a T-cell transfer model (Mottet et al., 2003). Based on this information, we next determined whether PG-MLA treatment influences Tregs numbers during chronic colitis. We analyzed the frequency of Tregs at the experimental end point in the spleen, MLN, and LP by flow cytometry in all experimental groups. Tregs made up of 7.1 % of the cells (gated on CD4+ T cells) in the spleen during chronic colitis in vehicle-treated mice. The percentages of similar gated Tregs in the spleen were significantly increased to 18.2% after PG-MLA treatment as compared to vehicle alone. Furthermore, Tregs in the MLN and LP of PG-MLA-treated mice demonstrated a marked increase in percentages as compared to vehicle-treated mice (Figure 5).

Fig. 5.

PG-MLA treatment increases frequency of Tregs. Splenic, MLNs and LP lymphocytes were isolated from the three groups of mice as described in Figure 2 and stained for CD4+ FoxP3+ cell markers and analyzed using flow cytometry. The numbers in the upper right quadrant indicate the total percentage of CD4+ FoxP3+ T cells. Data from a representative of three independent experiments are shown.

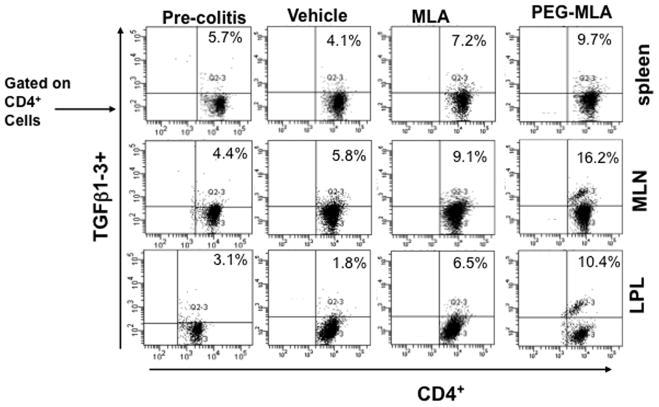

PG-MLA modulates TGF-β1-3 expression during colitis

Inadequate TGF-β signaling in T cells has been implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory disease including IBD (Monteleone et al., 2004). It has been shown that TGF-β plays a unique role in inducing the expression of Foxp3 (Chen et al., 2003) to mediate the tolerance. In the present study, we examined whether PG-MLA mediates TGF-β1-3 induction during chronic colitis. The percentage of CD4+ T cells that express TGF-β1-3 significantly increased in the spleen, MLN and LP of mice that received PG-MLA as compared to vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 6). These findings indicate that PG-MLA treatment considerably increased the frequency of TGF-β1-3 expressing CD4+ T cells in the spleen, MLN and LP as compared to vehicle treated mice.

Fig. 6.

PG-MLA enhances frequency of CD4+TGF-β1-3+ cells. Splenic, MLNs and LP lymphocytes were isolated from the three groups of mice as described in Figure 2 and stained for CD4+ TGF-β1-3+ cell markers using flow cytometry. The numbers in the upper right quadrant indicate the total percentage of CD4+ TGF-β1-3+ T cells. Data from a representative of three independent experiments are shown.

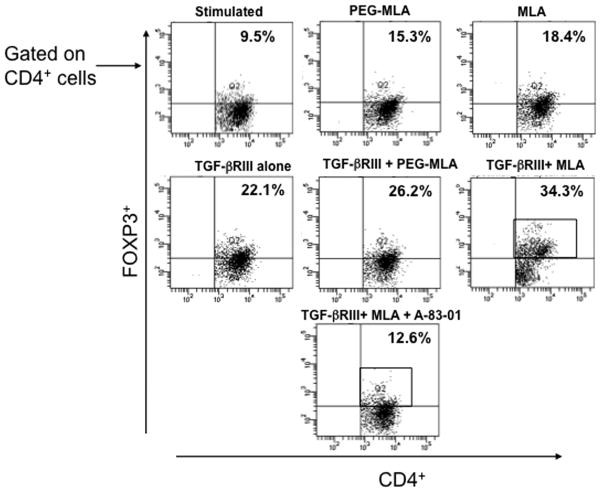

PG-MLA increases frequency of Tregs mediated through TGF-βRIII interactions

TGF-βRIII is a transmembrane proteoglycan binds with high affinity to all three TGF-β isoforms. TGF-βRIII functions by first binding to TGF-β, then transferring cytokine signals to its signaling receptors TGF-βRI and TGF-βRII. To date one good approach to inhibit the TGF-β signaling pathways is using inhibitors of TGF-β receptor kinases (Massague, 2008). To this end, we examined whether increase in the frequency of Tregs by PG-MLA is mediated via TGF-βRIII interactions and whether small molecule inhibitors can reverse the enhancement of Tregs. We tested this by in-vitro analysis using purified T cells from MLN. T cells at a density of 106 cells/ml in complete medium were activated using CD3 and CD28 mAb in the presence or absence of TGFβRIII and/or TGF-βRI kinase inhibitors VI (10μM) (A-83-01, Calbiochem) for 48 hrs. The results indicate that TGF-βRIII enhances Tregs frequency in PG-MLA induced group as compared to vehicle treatment alone (Fig. 7). Interestingly, the increase of Tregs by PG-MLA reversed after using TGF-βR1 kinase inhibitors as compared to vehicle control. These results clearly suggest that PG-MLA enhances the frequency of Tregs through TGF-β signaling.

Fig. 7.

An increase in frequency of Tregs is mediated through TGF-βRIII interactions signaling. The purified MLNs lymphocytes were isolated from naïve mice at a density of 106 cells/ml in complete medium containing 20 μg/ml of PG-MLA/MLA and cultured with/without 20 ng/ml of recombinant mouse TGF-βRIII with or without TGF-βR1 kinase inhibitors for two day with CD3 and CD28 activation. Changes in the mean percentage of Foxp3 expression were compared within groups (Panel A). The numbers in the upper right quadrant indicate the total percentage of Foxp3 expressing cells. Data represent the total frequency of cells± SEM from three independent experiments. Asterisks (*), indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.01) between vehicle and PG-MLA treated groups.

PG-MLA reduces STAT1/3 activation and diminishes Smad7 expression in the secondary lymphoid organs of colitic mice

It is well established that, in both IBD and experimental colitis, the expression of Smad7 increases with severity of the disease (Monteleone et al., 2001). Further, STAT1 and STAT3 have also been shown to play a major role in the progression of colitis (Schreiber et al., 2002; Sugimoto, 2008). In the present study we found that PG-MLA reduces both STAT1 and STAT3 activation in the mucosal sites when compared to vehicle control mice in the IL-10−/− colitic mouse (Fig. 8A). Moreover, PG-MLA also reduced the Stat1 activation at effector sites (LPL) with minimal effects in spleen and MLN. PG-MLA reduces the expression and immunoreactive score of intestinal Smad7 expression when compared to vehicle control mice (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

PG-MLA reduces the activation of STAT1/3 and expression of Smad7. The cells from spleen and intestinal tissues from vehicle and PG-MLA treated IL-10−/− mice were examined for changes in activation of STAT1/3 and expression of Smad7 by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry. (A) Representative overlaying histogram of (B) Representative staining of indicated end-points in serial sections from vehicle (n = 6), and PG-MLA treated (n = 6) groups. The immunoreactive scoring was done at 10x magnifications. (C) Quantification of indicated end-points of experiment. The Smad7 expression is elevated in vehicle treated IL-10−/− mice as compared to PG-MLA treatment. Asterisks (*), indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.01) between vehicle and PG-MLA treated groups.

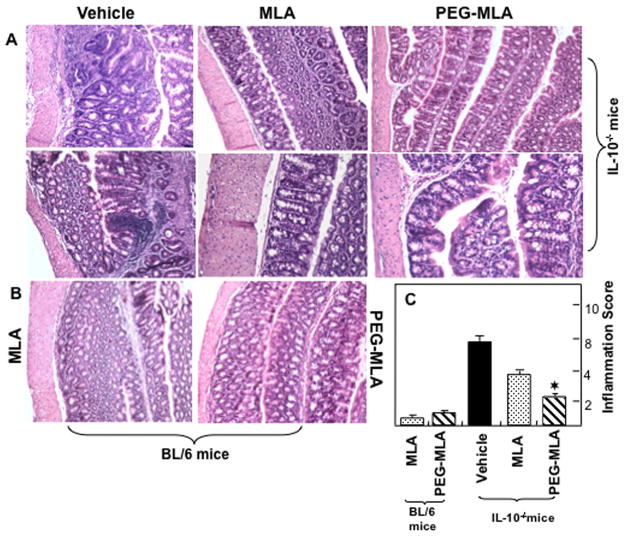

Severity of colitis correlates with inflammatory scores

The presence of colitis in mice after PG-MLA treatment was also studied by histology (Fig. 9). The colon histology of normal BL/6 mice demonstrated extensive hypertrophied epithelial layers at multiple sites, with only a few inflammatory infiltrates mainly composed of lymphocytes. The gross pathologic changes in vehicle treated IL-10−/− mice included small multi focal infiltrates composed of lymphoid aggregates in the LP of the colon. These infiltrates consisted of lymphocytes and occasionally small numbers of neutrophils (Fig. 9A & B). The cellular infiltrates and inflammatory score decreased significantly in the group of mice that received PG-MLA treatment as compared to vehicle. These data show that PG-MLA treatment reduces the severity of the disease as well as inflammation score when compared with their vehicle-treated control counterparts.

Fig. 9.

Histological characterization and inflammation score after PG-MLA treatment. Histological sections of colon from the groups of mice are presented (as described in Fig 1). Vehicle treated IL-10−/− mice (upper panel A) showed significant lymphocyte infiltration and distortion of glands, while MLA or PG-MLA treated mice (lower panel B) showed markedly decreased lymphocyte infiltration. The pathologic changes included diffuse leukocyte infiltrates, and thickening of the LP in the area of distorted crypts in the colon. The inflammation score of these groups are presented in Fig. 9C. Representative sections from three separate experiments (20X magnification), with groups containing six mice each.

Discussion

The adipocyte-derived hormone leptin is primarily known for control of appetite and obesity. Leptin is also recognized as a proinflammatory cytokine and plays a potent role in controlling autoimmune diseases (Dixit et al., 2004; Otero et al., 2006). More recently, a key piece of the puzzle regarding the role of leptin in autoimmune diseases has been put in place and suggests a direct link with Tregs anergy and hyporesponsiveness (De Rosa et al., 2007). Moreover, it has been proposed that leptin may also control immune self-tolerance by affecting Tregs responsiveness and function. It is well known that Foxp3 plays an important role in the control of intestinal inflammation (Coombes et al., 2005) and naturally arising CD4+ CD25+ Tregs have been shown to prevent or even cure disease in T-cell transfer models of colitis (Read et al., 2000; Mottet et al., 2003). We demonstrate in the present study the effects of leptin on intestinal inflammation using a spontaneous model of chronic colitis. The results illustrate that the use of a leptin blocker, PG-MLA, ameliorates chronic colitis by restoring TGF-β1-3 signaling through the reduction of Smad7 expression and dampens STAT1 and STAT3 activation leading to the increasing the numbers of Tregs. The PG-MLA-mediated increase in Tregs numbers may contribute to the reduction of inflammatory cytokine expression and disease severity in chronic colitic mice. These data suggest a link between inflammation and nutritional status that may contribute to the regulation of immune self-tolerance by increasing Tregs responsiveness and function.

Leptin has been examined in various rodent models of colitis. In rats, after TNBS induction of colitis, leptin level increases correspond with a decrease in food intake and body weight loss (Barbier et al., 1998). Moreover, in these rats, severity of colitis also correlated with plasma leptin levels. In contrast to these data, in IL-2−/− mice, it has been reported that leptin concentrations were lower in the fed state than in either pair-fed or freely fed controls, and serum leptin concentration during inflammation may not reflect the degree of adiposity (Gaetke et al., 2002). Taken together, increases in serum leptin levels in IBD patients and experimental colitis in mice, as compared to normal healthy counterparts (Barbier et al., 1998; Tuzun et al., 2004; Karmiris et al., 2006; Karmiris et al., 2008), corroborates our observation in the present study.

Serum amyloid A protein (SAA) has been shown to be elevated in many inflammatory conditions including CD, rheumatoid arthritis and chronic sepsis (De Beer et al., 1982). The presence of elevated serum SAA and IL-6 levels is significant as SAA regression is an indication of clinical improvement of CD (Mandelstam et al., 1989). In the present study, we observed similar decreases in SAA levels in PG-MLA-treated mice when compared to vehicle-treated mice. Increased expression of mRNA for TNF-α and IL-6 have also been reported in IL-2−/− mice (Autenrieth et al., 1997). In CD patients, elevated IL-6 levels in serum and mucosal biopsies have been reported (Reimund et al., 1996), and in the absence of corticosteroid treatment, patient IL-6 serum levels correlate with disease activity (Holtkamp et al., 1995). A similar finding has been found with TNF-α in colon tissue (Gaetke et al., 2002). In IBD, TNF-α levels have been found to be elevated in tissue and secretary fluids as well as a corresponding increase in the numbers of TNF-α-producing LP cells (Reimund et al., 1996). TNF-α has also been shown to lead to and attenuate the development of colitis in certain murine models of colitis (Powrie et al., 1994). In the present study, we demonstrate that the increase in spontaneous secretion of TNF-α and IL-6 levels in the serum correlates with severity of colitis in mice that received vehicle and is reduced in mice that received PG-MLA. Similarly, CCL2 and CXCL5, a murine homolog of ENA-78, are elevated in experimental models of colitis as well as in mucosal tissues in IBD patients (Keates et al., 1997; McCormack et al., 2001; Scheerens et al., 2001). It has been reported that CCL-2 knockout mice are protected after dinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (DNBS)-mediated colitis induction when compared to wild type control mice (Khan et al., 2006). Similarly, topical antisense oligonucleotide therapy against CXCL5 reduces murine colitis (Kwon et al., 2005). Here, we have also noticed a significant decrease in systemic CCL2 and CXCL5 after PG-MLA treatment when compared to vehicle-treated mice suggesting a diminishment in inflammation and correlating with a protection from colitis.

It has been shown that experimental granulomatous colitis in mice can be abrogated by the induction of TGF-β-mediated oral tolerance (Neurath et al., 1996). In recent studies, much attention has been focused that supports an important role for TGF-β in peripheral generation, homoeostatic proliferation, expansion and or function of Tregs (Chen et al., 2003). Here, we observed a significant increase in TGF-β expressing CD4+T cells in the spleen, MLN and LP of mice that received PG-MLA as compared to vehicle treated mice. Our data support previous work that demonstrates that PG-MLA-mediated induction of TGF-β producing CD4+ T cells inhibits mucosal T helper function, down regulates Th1 cytokine expression and increases Tregs numbers. After induction, the numbers of Tregs are increased in the secondary lymphoid organs MLN and LP, where TGF-β producing CD4+ T cells mediate suppressive effects on antigen-activated CD4+ T cells and macrophages that might otherwise cause inflammation and disease development and progression. These findings are supported by many other studies (Miller et al., 1991; Neurath et al., 1996). TGF-β-producing CD4+ T cells also support the induction of Tregs as evidenced by the many published studies demonstrating that naïve peripheral T cells may acquire a regulatory phenotype under the influence of TGF-β treatment both in-vitro and in-vivo (Yamagiwa et al., 2001; Zheng et al., 2002).

Several studies in the past have highlighted the important role of STAT1 and STAT3 in the pathophysiology of colonic inflammation (Schreiber et al., 2002; Plevy, 2005; Sugimoto, 2008; Lim, 2011). It has been shown that total STAT3 protein increased in both UC and CD patients as compared to non-inflammatory patients and pSTAT3 in tissue sections is also correlated with histological degree of inflammation (Mudter et al., 2005). Further, activation of the IL6/STAT3 cascade in LP T cells induced prolonged survival of pathogenic T cells, and indeed inactivation of these cascades attenuated chronic inflammation (Atreya et al., 2000). We also demonstrate here that a significant decrease in STAT1 and STAT3 activation occurs after PG-MLA, but not vehicle treatment, in the spleen, MLN and LP cells. Furthermore, we noticed a more dramatic decrease in STAT1 activation in LP T cells in PG-MLA-treated colonic mice. Our results are corroborated by additional reports demonstrating that inactivation of the leptin/STAT3 signaling cascades results in suppression of acquired immune T-cell mediated colitis (Siegmund et al., 2002a).

The inflamed intestine of IBD patients shows marked over-expression of Smad7 (Monteleone et al., 2001). Smad7 can be induced by STAT1 and that the blocking of Smad7 leads to down regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine production in isolated mucosal LP mononuclear cells and cell lines (Monteleone et al., 2001). Moreover, restoration of TGF-β1- signaling by inhibition of Smad7 reduced Th1 cytokines as well as associated transcription factor STAT1 in TNBS and sulfonic acid models of colitis (Boirivant et al., 2006). In the present study, we also observed that treatment with PG-MLA reduces Smad7 expression as compared to vehicle treatment and that this PG-MLA-mediated reduction in Smad7 expression correlated with the inhibition of both STAT1 and STAT3 activation, presumably influencing TGF-β1-3 expression and signaling that leads to an increase in Tregs.

Leptin affects the generation and proliferation capacity of Tregs that are well known for their central role in control of peripheral immune tolerance (De Rosa et al., 2007). In mice, leptin and its receptor deficiency are shown to increase the absolute number, percentage and activities of Tregs (Matarese et al., 2001) with a resistance to autoimmune disease (Klingenberg et al., 2010). Leptin-deficient (ob/ob) mice showed 72% reduction in colitis severity and leptin treatment eliminates resistance against experimentally induced colitis (Siegmund et al., 2002b). Increased leptin levels correlates with severity of disease in IBD, experimental colitis and multiple sclerosis (MS) patients and inversely correlates with the numbers of circulating Tregs (Matarese et al., 2005a). It has also been shown that experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) can be ameliorated by increasing the percentage of Tregs in wild type mice after leptin receptor fusion protein treatment (Matarese et al., 2005a). In the present study, we observed a significant increase in leptin levels in experimental colitis that correlates with a decrease in circulating Tregs and an increase in disease severity. However, the use of PG-MLA reversed the disease severity by increasing the number of both mucosal and systemic circulatory Tregs. In summary, the present study expands the notion that blocking leptin activity enhances Tregs numbers and partially mediates colitis through restoration of TGF-β1-β2-β3 signaling and by decreasing STAT1/3 activation and Smad7 expression. Further, this study will open an avenue for future therapeutical research on leptin hormone involvement in autoimmune diseases, especially for IBD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part by NIH grants R56 DK087836, R01 AT006888, R01 ES019313, R01 MH094755, P01 AT003961, Research and Development Funds from the University of South Carolina School of Medicine and Intramural Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement:

The authors declare not having any competing interests that might influence this study or no involvement of study sponsors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Atreya R, Mudter J, Finotto S, Mullberg J, Jostock T, Wirtz S, Schutz M, Bartsch B, Holtmann M, Becker C, Strand D, Czaja J, Schlaak JF, Lehr HA, Autschbach F, Schurmann G, Nishimoto N, Yoshizaki K, Ito H, Kishimoto T, Galle PR, Rose-John S, Neurath MF. Blockade of interleukin 6 trans signaling suppresses T-cell resistance against apoptosis in chronic intestinal inflammation: evidence in crohn disease and experimental colitis in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6:583–588. doi: 10.1038/75068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autenrieth IB, Bucheler N, Bohn E, Heinze G, Horak I. Cytokine mRNA expression in intestinal tissue of interleukin-2 deficient mice with bowel inflammation. Gut. 1997;41:793–800. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.6.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auwerx J, Staels B. Leptin. Lancet. 1998;351:737–742. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)06348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier M, Cherbut C, Aube AC, Blottiere HM, Galmiche JP. Elevated plasma leptin concentrations in early stages of experimental intestinal inflammation in rats. Gut. 1998;43:783–790. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.6.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier M, Vidal H, Desreumaux P, Dubuquoy L, Bourreille A, Colombel JF, Cherbut C, Galmiche JP. Overexpression of leptin mRNA in mesenteric adipose tissue in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2003;27:987–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg DJ, Davidson N, Kuhn R, Muller W, Menon S, Holland G, Thompson-Snipes L, Leach MW, Rennick D. Enterocolitis and colon cancer in interleukin-10-deficient mice are associated with aberrant cytokine production and CD4(+) TH1-like responses. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1010–1020. doi: 10.1172/JCI118861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boirivant M, Pallone F, Di Giacinto C, Fina D, Monteleone I, Marinaro M, Caruso R, Colantoni A, Palmieri G, Sanchez M, Strober W, MacDonald TT, Monteleone G. Inhibition of Smad7 with a specific antisense oligonucleotide facilitates TGF-beta1-mediated suppression of colitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1786–1798. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsellino G, Kleinewietfeld M, Di Mitri D, Sternjak A, Diamantini A, Giometto R, Hopner S, Centonze D, Bernardi G, Dell’Acqua ML, Rossini PM, Battistini L, Rotzschke O, Falk K. Expression of ectonucleotidase CD39 by Foxp3+ Treg cells: hydrolysis of extracellular ATP and immune suppression. Blood. 2007;110:1225–1232. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-064527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, Lei KJ, Li L, Marinos N, McGrady G, Wahl SM. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25− naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes JL, Robinson NJ, Maloy KJ, Uhlig HH, Powrie F. Regulatory T cells and intestinal homeostasis. Immunol Rev. 2005;204:184–194. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X, Jin Y, Hofseth AB, Pena E, Habiger J, Chumanevich A, Poudyal D, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS, Singh UP, Hofseth LJ. Resveratrol suppresses colitis and colon cancer associated with colitis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2010;3:549–559. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Beer FC, Mallya RK, Fagan EA, Lanham JG, Hughes GR, Pepys MB. Serum amyloid-A protein concentration in inflammatory diseases and its relationship to the incidence of reactive systemic amyloidosis. Lancet. 1982;2:231–234. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gaetano A, Greco AV, Benedetti G, Capristo E, Castagneto M, Gasbarrini G, Mingrone G. Increased resting lipid oxidation in Crohn’s disease. J Paren & Ent Nut. 1996;20:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa V, Procaccini C, Cali G, Pirozzi G, Fontana S, Zappacosta S, La Cava A, Matarese G. A key role of leptin in the control of regulatory T cell proliferation. Immunity. 2007;26:241–255. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa V, Procaccini C, La Cava A, Chieffi P, Nicoletti GF, Fontana S, Zappacosta S, Matarese G. Leptin neutralization interferes with pathogenic T cell autoreactivity in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:447–455. doi: 10.1172/JCI26523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit VD, Schaffer EM, Pyle RS, Collins GD, Sakthivel SK, Palaniappan R, Lillard JW, Jr, Taub DD. Ghrelin inhibits leptin- and activation-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression by human monocytes and T cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:57–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI21134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt RO, Ludviksson BR, Gray B, Neurath M, Strober W. Induction and prevention of colonic inflammation in IL-2-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:566–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantini MC, Becker C, Monteleone G, Pallone F, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Cutting edge: TGF-beta induces a regulatory phenotype in CD4+CD25− T cells through Foxp3 induction and down-regulation of Smad7. J Immunol. 2004;172:5149–5153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Riejos P, Najib S, Santos-Alvarez J, Martin-Romero C, Perez-Perez A, Gonzalez-Yanes C, Sanchez-Margalet V. Role of leptin in the activation of immune cells. Med Inflamm. 2010;2010:568343. doi: 10.1155/2010/568343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuss IJ, Boirivant M, Lacy B, Strober W. The interrelated roles of TGF-beta and IL-10 in the regulation of experimental colitis. J Immunol. 2002;168:900–908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetke LM, Oz HS, de Villiers WJ, Varilek GW, Frederich RC. The leptin defense against wasting is abolished in the IL-2-deficient mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease. J Nut. 2002;132:893–896. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.5.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg GR, Fleming CR, Jeejeebhoy KN, Rosenberg IH, Sales D, Tremaine WJ. Controlled trial of bowel rest and nutritional support in the management of Crohn’s disease. Am J of Clin Nut. 1989;49:573–579. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.10.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunfeld C, Zhao C, Fuller J, Pollack A, Moser A, Friedman J, Feingold KR. Endotoxin and cytokines induce expression of leptin, the ob gene product, in hamsters. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2152–2157. doi: 10.1172/JCI118653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenkrug KJ. The leptin connection: regulatory T cells and autoimmunity. Immunity. 2007;26:143–145. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp W, Stollberg T, Reis HE. Serum interleukin-6 is related to disease activity but not disease specificity in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:123–126. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199503000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber S, Schramm C, Lehr HA, Mann A, Schmitt S, Becker C, Protschka M, Galle PR, Neurath MF, Blessing M. Cutting edge: TGF-beta signaling is required for the in vivo expansion and immunosuppressive capacity of regulatory CD4+CD25+T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:6526–6531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmiris K, Koutroubakis IE, Kouroumalis EA. Leptin, adiponectin, resistin, and ghrelin--implications for inflammatory bowel disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:855–866. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmiris K, Koutroubakis IE, Xidakis C, Polychronaki M, Voudouri T, Kouroumalis EA. Circulating levels of leptin, adiponectin, resistin, and ghrelin in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:100–105. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000200345.38837.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keates S, Keates AC, Mizoguchi E, Bhan A, Kelly CP. Enterocytes are the primary source of the chemokine ENA-78 in normal colon and ulcerative colitis. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G75–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.1.G75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan WI, Motomura Y, Wang H, El-Sharkawy RT, Verdu EF, Verma-Gandhu M, Rollins BJ, Collins SM. Critical role of MCP-1 in the pathogenesis of experimental colitis in the context of immune and enterochromaffin cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liv Physiol. 2006;291:G803–811. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00069.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg R, Lebens M, Hermansson A, Fredrikson GN, Strodthoff D, Rudling M, Ketelhuth DF, Gerdes N, Holmgren J, Nilsson J, Hansson GK. Intranasal immunization with an apolipoprotein B-100 fusion protein induces antigen-specific regulatory T cells and reduces atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:946–952. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.202671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad A, Lehrke M, Schachinger V, Seibold F, Stark R, Ochsenkuhn T, Parhofer KG, Goke B, Broedl UC. Resistin is an inflammatory marker of inflammatory bowel disease in humans. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:1070–1074. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f16251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon JH, Keates AC, Anton PM, Botero M, Goldsmith JD, Kelly CP. Topical antisense oligonucleotide therapy against LIX, an enterocyte-expressed CXC chemokine, reduces murine colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liv Physiol. 2005;289:G1075–1083. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00073.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim BO. Coriolus versicolor suppresses inflammatory bowel disease by Inhibiting the expression of STAT1 and STAT6 associated with IFN-gamma and IL-4 expression. Phyto Res. 2011;25:1257–1261. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord GM, Matarese G, Howard JK, Baker RJ, Bloom SR, Lechler RI. Leptin modulates the T-cell immune response and reverses starvation-induced immunosuppression. Nature. 1998;394:897–901. doi: 10.1038/29795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovato P, Brender C, Agnholt J, Kelsen J, Kaltoft K, Svejgaard A, Eriksen KW, Woetmann A, Odum N. Constitutive STAT3 activation in intestinal T cells from patients with Crohn’s disease. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16777–16781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207999200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelstam P, Simmons DE, Mitchell B. Regression of amyloid in Crohn’s disease after bowel resection. A 19-year follow-up. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:324–326. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198906000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matarese G, Carrieri PB, La Cava A, Perna F, Sanna V, De Rosa V, Aufiero D, Fontana S, Zappacosta S. Leptin increase in multiple sclerosis associates with reduced number of CD4(+) CD25+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005a;102:5150–5155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408995102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matarese G, Di Giacomo A, Sanna V, Lord GM, Howard JK, Di Tuoro A, Bloom SR, Lechler RI, Zappacosta S, Fontana S. Requirement for leptin in the induction and progression of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2001;166:5909–5916. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.5909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matarese G, Moschos S, Mantzoros CS. Leptin in immunology. J Immunol. 2005b;174:3137–3142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack G, Moriarty D, O’Donoghue DP, McCormick PA, Sheahan K, Baird AW. Tissue cytokine and chemokine expression in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Res. 2001;50:491–495. doi: 10.1007/PL00000223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A, Lider O, Weiner HL. Antigen-driven bystander suppression after oral administration of antigens. J Exp Med. 1991;174:791–798. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone G, Caruso R, Pallone F. Role of Smad7 in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5664–5668. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i40.5664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone G, Kumberova A, Croft NM, McKenzie C, Steer HW, MacDonald TT. Blocking Smad7 restores TGF-beta1 signaling in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:601–609. doi: 10.1172/JCI12821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone G, Pallone F, MacDonald TT. Smad7 in TGF-beta-mediated negative regulation of gut inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:513–517. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottet C, Uhlig HH, Powrie F. Cutting edge: cure of colitis by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:3939–3943. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudter J, Weigmann B, Bartsch B, Kiesslich R, Strand D, Galle PR, Lehr HA, Schmidt J, Neurath MF. Activation pattern of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) factors in inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:64–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao A, Afrakhte M, Moren A, Nakayama T, Christian JL, Heuchel R, Itoh S, Kawabata M, Heldin NE, Heldin CH, ten Dijke P. Identification of Smad7, a TGFbeta-inducible antagonist of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 1997;389:631–635. doi: 10.1038/39369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neurath MF, Fuss I, Kelsall BL, Presky DH, Waegell W, Strober W. Experimental granulomatous colitis in mice is abrogated by induction of TGF-beta-mediated oral tolerance. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2605–2616. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero M, Lago R, Gomez R, Dieguez C, Lago F, Gomez-Reino J, Gualillo O. Towards a pro-inflammatory and immunomodulatory emerging role of leptin. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:944–950. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer G, Aurrand-Lions M, Contassot E, Talabot-Ayer D, Ducrest-Gay D, Vesin C, Chobaz-Peclat V, Busso N, Gabay C. Indirect effects of leptin receptor deficiency on lymphocyte populations and immune response in db/db mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:2899–2907. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plevy S. A STAT need for human immunologic studies to understand inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:73–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powrie F, Leach MW, Mauze S, Menon S, Caddle LB, Coffman RL. Inhibition of Th1 responses prevents inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhi CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 1994;1:553–562. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao PE, Petrone AL, Ponath PD. Differentiation and expansion of T cells with regulatory function from human peripheral lymphocytes by stimulation in the presence of TGF-{beta} J Immunol. 2005;174:1446–1455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read S, Malmstrom V, Powrie F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 plays an essential role in the function of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory cells that control intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:295–302. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimund JM, Wittersheim C, Dumont S, Muller CD, Kenney JS, Baumann R, Poindron P, Duclos B. Increased production of tumour necrosis factor-alpha interleukin-1 beta, and interleukin-6 by morphologically normal intestinal biopsies from patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1996;39:684–689. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.5.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud D, Angel LA, Cerf M, Carduner MJ, Melchior JC, Sautier C, Rene E, Apfelbaum M, Mignon M. Mechanisms of decreased food intake during weight loss in adult Crohn’s disease patients without obvious malabsorption. Am J Clin Nut. 1994;60:775–781. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheerens H, Hessel E, de Waal-Malefyt R, Leach MW, Rennick D. Characterization of chemokines and chemokine receptors in two murine models of inflammatory bowel disease: IL-10−/− mice and Rag-2−/− mice reconstituted with CD4+CD45RBhigh T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1465–1474. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200105)31:5<1465::AID-IMMU1465>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S, Rosenstiel P, Hampe J, Nikolaus S, Groessner B, Schottelius A, Kuhbacher T, Hamling J, Folsch UR, Seegert D. Activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 1 in human chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2002;51:379–385. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.3.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund B, Lehr HA, Fantuzzi G. Leptin: a pivotal mediator of intestinal inflammation in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002a;122:2011–2025. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund B, Lehr HA, Fantuzzi G. Leptin: a pivotal mediator of intestinal inflammation in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002b;122:2011–2025. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk DB, Payne-James J. Inflammatory bowel disease: nutritional implications and treatment. Proc Nut Soc. 1989;48:355–361. doi: 10.1079/pns19890051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh UP, Singh S, Taub DD, Lillard JW., Jr Inhibition of IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 abrogates colitis in IL-10−/− mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:1401–1406. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitaraman S, Liu X, Charrier L, Gu LH, Ziegler TR, Gewirtz A, Merlin D. Colonic leptin: source of a novel proinflammatory cytokine involved in IBD. FASEB. 2004;18:696–698. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0422fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K. Role of STAT3 in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5110–5114. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Hanada T, Mitsuyama K, Yoshida T, Kamizono S, Hoshino T, Kubo M, Yamashita A, Okabe M, Takeda K, Akira S, Matsumoto S, Toyonaga A, Sata M, Yoshimura A. CIS3/SOCS3/SSI3 plays a negative regulatory role in STAT3 activation and intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2001;193:471–481. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.4.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuzun A, Uygun A, Yesilova Z, Ozel AM, Erdil A, Yaman H, Bagci S, Gulsen M, Karaeren N, Dagalp K. Leptin levels in the acute stage of ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:429–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa L, Doody J, Massague J. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta/SMAD signalling by the interferon-gamma/STAT pathway. Nature. 1999;397:710–713. doi: 10.1038/17826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagiwa S, Gray JD, Hashimoto S, Horwitz DA. A role for TGF-beta in the generation and expansion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells from human peripheral blood. J Immunol. 2001;166:7282–7289. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng SG, Gray JD, Ohtsuka K, Yamagiwa S, Horwitz DA. Generation ex vivo of TGF-beta-producing regulatory T cells from CD4+CD25− precursors. J Immunol. 2002;169:4183–4189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]