Update to: European Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 19; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2011.9; published online 9 February 2011

1. Disease characteristics

1.1 Name of the disease (synonyms)

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome, gorlin syndrome, basal cell nevus syndrome.

1.2 OMIM# of the disease

109400.

1.3 Name of the analyzed genes or DNA/chromosome segments

PTCH1.

1.4 OMIM# of the gene(s)

601309.

1.5 Mutational spectrum

Point mutations, small and large deletions, insertions and splicing mutations.

1.6 Analytical methods

Sequencing of all PTCH1 exons and their intron–exon boundaries,1 MLPA, QMP (quantitative multiplex fluorescent PCR) or array-CHG for deletions spanning the whole gene.2, 3 Based on the type of mutations most frequently detected,1 start with sequencing (point mutations), followed by MLPA, QMP or array-CHG (large mutations). In patients who test negative for mutations in PTCH1, promoter analysis, testing of SUFU4 and PTCH25 may be considered.

The detection specificity of sequencing is almost 100% for point mutations and small deletions and insertions. MLPA, QMP or array-CHG is applicable only for exon-spanning mutations (<5% of all mutations); the detection specificity is 95–100%.

Pathogenicity of missense PTCH1 alterations is verified by testing a set of 100 controls (200 chromosomes) and by in silico prediction methods.

1.7 Analytical validation

Mutation is confirmed by testing an independent biological sample from the proband or an affected relative. If one exon is deleted or duplicated, the mutation is confirmed by utilizing a second technique or a kit with different primers. To confirm splicing mutations, testing is conducted on cDNA extracted from a lymphoblastoid cell line.

1.8 Estimated frequency of the disease (incidence at birth (‘birth prevalence') or population prevalence)

This syndrome existed during Dynastic Egyptian times, as shown by a constellation of findings compatible with the syndrome in mummies dating back to 1000 b.c.6 In 1992, Farndon et al7 estimated that the minimum prevalence is 1 per 57 000.8 An almost identical value was noted by Pratt and Jackson.9 A study in the North West of England showed that the disease affects 1 in 55 600 people.10 In Italy, the incidence (1/256 000)11 of the disease appears to be lower than in Australia (1/164 000)12 and the United Kingdom.10 Rahbari and Mehregan13 noted that 2% of patients under 45 years of age with basal cell carcinomas have the syndrome. Recently two new studies reported the incidence of the syndrome in Korea,14 and in France.15 Further investigations could improve the detected frequency of the NBCC syndrome by introducing revised criteria16 or restoring the neglected criterion ameloblastoma (AML).17, 18 The AML represents a peculiar sign of this hereditary disorder that might be useful, as keratocystic odontogenic tumors, for the identification of NBCCS.

1.9 If applicable, prevalence in the ethnic group of investigated person

Not applicable.

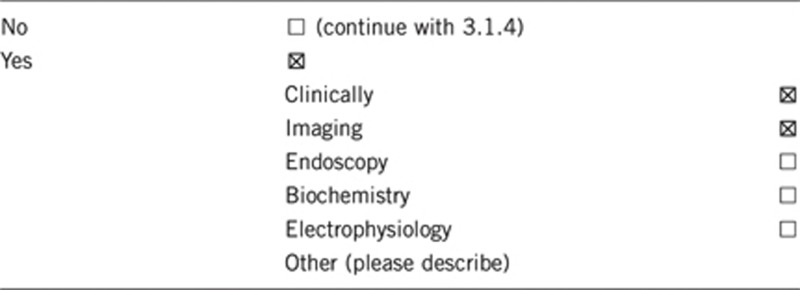

1.10 Diagnostic setting

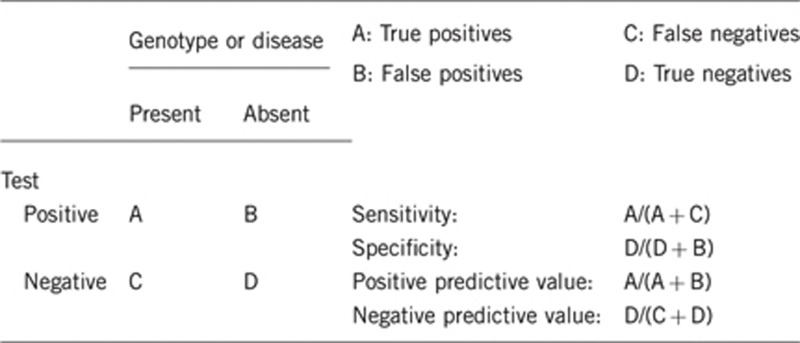

2. Test characteristics

2.1 Analytical sensitivity (proportion of positive tests if the genotype is present)

Nearly 100% with germ-line mutations.

2.2 Analytical specificity (proportion of negative tests if the genotype is not present)

Nearly 100%.

2.3 Clinical sensitivity (proportion of positive tests if the disease is present)

Clinical sensitivity can be dependent on variable factors such as age or family history. In such cases a general statement should be given, even if a quantification can only be made case by case.

Clinical sensitivity applying stringent clinical criteria with accurate diagnosis is nearly 87% for PTCH1 and SUFU mutations together, should increase if testing for PTCH1 promoter and PTCH2 become routine.

2.4 Clinical specificity (proportion of negative tests if the disease is not present)

The clinical specificity can be dependent on variable factors such as age or family history. In such cases a general statement should be given, even if a quantification can only be made case by case.

Nearly 100%.

2.5 Positive clinical predictive value (lifetime risk to develop the disease if the test is positive)

Approximately 92%.

2.6 Negative clinical predictive value (probability of not developing the disease if the test is negative)

Assume an increased risk based on family history for a non-affected person. Allelic and locus heterogeneity may need to be considered.

Index case in that family had been tested:

Nearly 100%.

Index case in that family had not been tested:

Not a recommended approach.

3. Clinical utility

3.1 (Differential) diagnostics: The tested person is clinically affected (To be answered if in 1.10 ‘A' was marked)

After clinical examination by a trained dermatologist with a strong background in genetic counseling.

3.1.1 Can a diagnosis be made other than through a genetic test?

3.1.2 Describe the burden of alternative diagnostic methods to the patient

AP and lateral X-rays of the skull, an orthopantogram, chest X-ray, and spinal X-ray are generally necessary. Ultrasound examinations are required for detection of ovarian and cardiac fibromas.11, 19

3.1.3 How is the cost effectiveness of alternative diagnostic methods to be judged?

Not applicable.

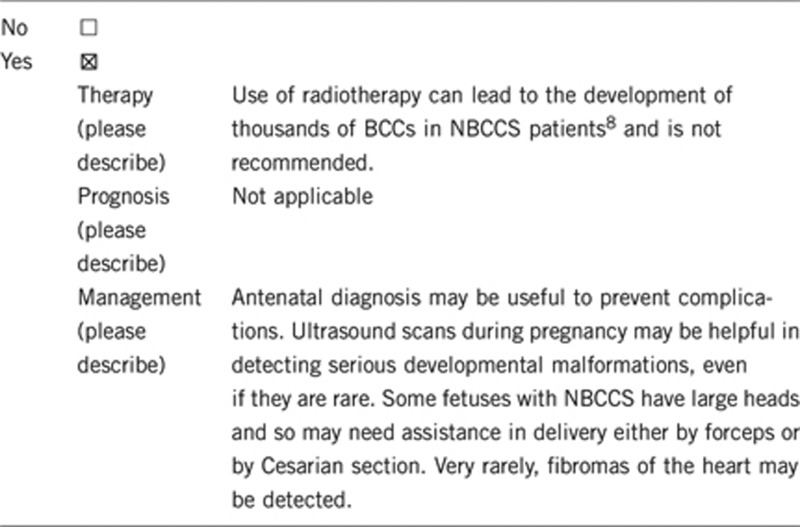

3.1.4 Will disease management be influenced by the result of a genetic test?

3.2 Predictive setting: The tested person is clinically unaffected but carries an increased risk based on family history (To be answered if in 1.10 ‘B' was marked)

3.2.1 Will the result of a genetic test influence lifestyle and prevention?

If the test result is positive (please describe) occipitofrontal circumference should be monitored throughout childhood; children should be evaluated for hydrocephalus if rapid enlargement occurs. The risk of medulloblastoma in early childhood warrants physical examination and developmental assessment twice yearly. The efficacy of regular neuroimaging has not been proven; frequent computer tomography should be avoided because of NBCCS-associated radiation sensitivity. Starting at the age of 8 years a yearly panoramic radiograph of the jaws is recommended.20 An at least annual examination of the skin from puberty is recommended, but as a lesion may suddenly become aggressive, the patient needs open access to the specialist, taking responsibility for treatment of the skin. Affected individuals should avoid sun exposure when possible, apply total sunblock and use protective clothing to cover the skin.21

If the test result is negative (no mutations or any pathogenic variant is found) intensified screening is not required.

3.2.2 Which options in view of lifestyle and prevention does a person at risk have if no genetic test has been done (please describe)?

Avoidance of sun exposure and regular dental examinations are recommended. In very young children developmental assessment and physical examinations are recommended twice yearly. Panoramic radiograph of jaws and regular skin examinations should be included in regular follow-up.

3.3 Genetic risk assessment in family members of a diseased person

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘C' was marked)

3.3.1 Does the result of a genetic test resolve the genetic situation in that family?

As NBCCS is an autosomal dominant disease with almost complete penetrance and high intra-familial phenotypic variability, affected individuals and their family members should be offered genetic counseling and testing.

NBCCS is caused when one copy of the PTCH1 gene pair contains a fault; this means that every child of a person with the syndrome has a 1 in 2 (50:50) chance of inheriting the faulty gene. The risk to family members is various, about 70–80% of individuals diagnosed with NBCCS have an affected parent and about 20–30% of probands have a de novo mutation. The risk to a sib of a proband depends on the genetic status of the parents: if a parent of the proband is affected, the risk to the sibs is 50% when the parents are clinically unaffected, the risk to the sibs of a proband appears to be low; if the disease-causing mutation cannot be detected in the DNA of the parent, the risk to sibs is low, but greater than that of the general population because the possibility of somatic mosaicism or germline mosaicism exists. The offspring of an individual with mild NBCCS caused by somatic mosaicism may have a risk of less than 50% of inheriting the disease-causing mutation. The risk to other family members depends upon the genetic status of the proband's parents; if a parent is affected, his or her family members are at risk.

3.3.2 Can a genetic test in the index patient save genetic or other tests in family members?

Yes, recommendation for screening applies only to mutation carriers and persons at risk.

3.3.3 Does a positive genetic test result in the index patient enable a predictive test in a family member?

Yes.

3.4 Prenatal diagnosis (To be answered if in 1.10 ‘D' was marked)

If one of the parents is affected, prenatal diagnosis is recommended.

3.4.1 Does a positive genetic test result in the index patient enable a prenatal diagnosis?

Prenatal diagnosis for pregnancies at increased risk is possible by analysis of DNA extracted from fetal cells obtained by amniocentesis (usually performed at about 15–18 weeks of gestation) or by chorionic villus sampling at about 10–12 weeks of gestation. The disease-causing allele of an affected family member must be identified or linkage established in the family before prenatal testing can be performed.

4. If applicable, further consequences of testing

Please assume that the result of a genetic test has no immediate medical consequences. Is there any evidence that a genetic test is nevertheless useful for the patient or his/her relatives? (Please describe)

Support for family life organization.

Enable assessment of a severe disease, known to be transmissible to next generations.

Efficiency of subsequent clinical management.

Risk calculation for unaffected relatives.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by EuroGentest, an EU-FP6-supported NoE, contract number 512148 (EuroGentest Unit 3: ‘Clinical genetics, community genetics and public health', Workpackage 3.2).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pastorino R, Cusano S, Nasti F, et al. Molecular characterization of Italian Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome patients. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:322–323. doi: 10.1002/humu.9317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musani V, Cretnik M, Situm M, Basta-Juzbasic A, Levanat S. Gorlin syndrome patient with large deletion in 9q22.32-q22.33 detected by quantitative multiplex fluorescent PCR. Dermatology. 2009;219:111–118. doi: 10.1159/000219247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowska B, Kutkowska-Kaźmierczak A, Stankiewicz P, et al. A girl with deletion 9q22.1-q22.32 including the PTCH and ROR2 genes identified by genome-wide array-CGH. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:1885–1889. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastorino L, Ghiorzo P, Nasti S, et al. Identification of a SUFU germline mutation in a family with Gorlin syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:1539–1543. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, Li J, Du J, et al. A missense mutation in PTCH2 underlies dominantly inherited NBCCS in a Chinese family. Med Genet. 2008;45:303–308. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.055343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satinoff MI, Wells C. Multiple basal cell naevus syndrome in ancient Egypt. Med Hist. 1969;13:294–297. doi: 10.1017/s0025727300014563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farndon PA, Del Mastro RG, Evans DG, Kilpatrick MW. Location of gene for Gorlin syndrome. Lancet. 1992;339:581–582. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90868-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DG, Birch JM, Orton CI. Brain tumours and the occurrence of severe invasive basal cell carcinoma in first degree relatives with Gorlin syndrome. Br J Neurosurg. 1991;5:643–646. doi: 10.3109/02688699109002890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MD, Jackson R. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. A 15-year follow-up of cases in Ottawa and the Ottawa Valley. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:964–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DG, Ladusans EJ, Rimmer S, Burnell LD, Thakker N, Farndon PA. Complications of the naevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: results of a population based study. J Med Genet. 1993;30:460–464. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.6.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Muzio L, Nocini PF, Savoia A, et al. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Clinical findings in 37 Italian affected individuals. Clin Genet. 1999;55:34–40. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1999.550106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanley S, Ratcliffe J, Hockey A, et al. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: review of 118 affected individuals. Am J Med Genet. 1994;50:282–290. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320500312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahbari H, Mehregan AH. Basal cell epithelioma (carcinoma) in children and teenagers. Cancer. 1982;49:350–353. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820115)49:2<350::aid-cncr2820490223>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn SG, Lim YS, Kim DK, Kim SG, Lee SH, Yoon JH. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: a retrospective analysis of 33 affected Korean individuals. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:458–462. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruvost-Balland C, Gorry P, Boutet N, et al. Clinical and genetic study in 22 patients with basal cell nevus syndrome. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2006;133:117–123. doi: 10.1016/s0151-9638(06)70861-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bree AF, Shah MR, BCNS Colloquium Group Consensus statement from the first international colloquium on basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS) Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:2091–2097. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponti G, Pastorino L, Pollio A, et al. Ameloblastoma: a neglected criterion for nevoid basal cell carcinoma (Gorlin) syndrome. Fam Cancer. 2012;11:411–418. doi: 10.1007/s10689-012-9529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastorino L, Pollio A, Pellacani G, et al. Novel PTCH1 mutations in patients with keratocystic odontogenic tumors screened for nevoid basal cell carcinoma (NBCC) syndrome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimonis VE, Mehta SG, Digiovanna JJ, Bale SJ, Pastakia B. Radiological features in 82 patients with nevoid basal cell carcinoma (NBCC or Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med. 2004;6:495–502. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000145045.17711.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Muzio L, Nocini P, Bucci P, Pannone G, Consolo U, Procaccini M. Early diagnosis of nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:669–674. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DG, Farndon PA.Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndromeIn: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP (eds): GeneReviewsSeattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle,2011 [PubMed]