Update to: European Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 19; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2011.49; published online 30 March 2011

1. DISEASE CHARACTERISTICS

1.1 Name of the disease (synonyms)

Joubert syndrome (JS); Joubert-Boltshauser syndrome; Joubert syndrome-related disorders (JSRD), including cerebellar vermis hypo/aplasia, oligophrenia, congenital ataxia, ocular coloboma, and hepatic fibrosis (COACH) syndrome; cerebellooculorenal, or cerebello-oculo-renal (COR) syndrome; Dekaban-Arima syndrome; Váradi-Papp syndrome or Orofaciodigital type VI (OFDVI) syndrome; Malta syndrome.

1.2 OMIM# of the disease

213300, 243910, 216360, 277170.

1.3 Name of the analysed genes or DNA/chromosome segments

JBTS1/INPP5E, JBTS2/TMEM216, JBTS3/AHI1, JBTS4/NPHP1, JBTS5/CEP290, JBTS6/TMEM67, JBTS7/RPGRIP1L, JBTS8/ARL13B, JBTS9/CC2D2A, JBTS10/OFD1, JBTS11/TTC21B*, JBTS12/KIF7, JBTS13/TCTN1, JBTS14/TMEM237, JBTS15/CEP41, JBTS16/TMEM138, JBTS17/C5orf42, JBTS18/TCTN3, JBTS19/ZNF423*, TCTN2, JBTS20/TMEM231.

*only heterozygous mutations identified in patients with Joubert syndrome to date.

1.4 OMIM# of the gene(s)

613037, 613277, 608894, 607100, 610142, 609884, 610937, 608922, 612013, 300170, 612014, 611254, 609863, 614423, 610523, 614459, 614571, 614815, 604557, 613846, 614970.

1.5 Mutational spectrum

Missense and nonsense mutations, splice site mutations, deletions, insertions. Genomic rearrangements so far reported only for NPHP1 (homozygous deletions represent >95% mutations) and CEP290 (heterozygous multiexon deletion reported in a single patient). Marked allelic heterogeneity, with several mutations reported in genes that underwent extensive mutation screening. Gene–phenotype correlations are known for selected genes (about 50% patients with COR phenotype and about 75% patients with COACH phenotype have mutations in CEP290 and TMEM67 genes, respectively).

1.6 Analytical methods

Direct sequencing of coding genomic regions and splice site junctions; multiplex microsatellite analysis for detection of NPHP1 homozygous deletion. Possibly, qPCR or targeted array-CGH for detection of genomic rearrangements in other genes.

1.7 Analytical validation

Direct sequencing of both DNA strands; verification of sequence and qPCR results in an independent experiment.

1.8 Estimated frequency of the disease (incidence at birth-‘birth prevalence'-or population prevalence)

No good population-based data on JSRD prevalence have been published. A likely underestimated frequency between 1/80 000 and 1/100 000 live births is based on unpublished data.

1.9 If applicable, prevalence in the ethnic group of investigated person

In Ashkenazi Jews, the estimated carrier frequency of the founder mutation p.R73L in the TMEM216 gene is about 1%.

There is a higher prevalence of JS also in the French Canadian population living in the province of Quebec (Canada) due to multiple founder mutations in at least three distinct genes (C5orf42, CC2D2A, and TMEM231).

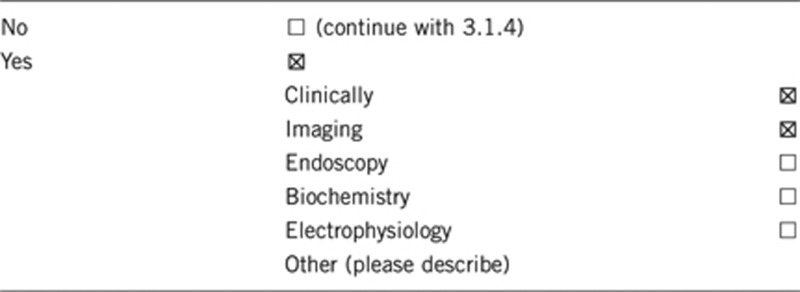

1.10 Diagnostic setting

Comment:

The early detection of breathing abnormalities and/or oculomotor apraxia is suggestive of JS and related disorders. Definite diagnosis is made based on the identification of the characteristic hindbrain malformation on brain imaging, that is, the ‘molar tooth sign' or its component features.

2. TEST CHARACTERISTICS

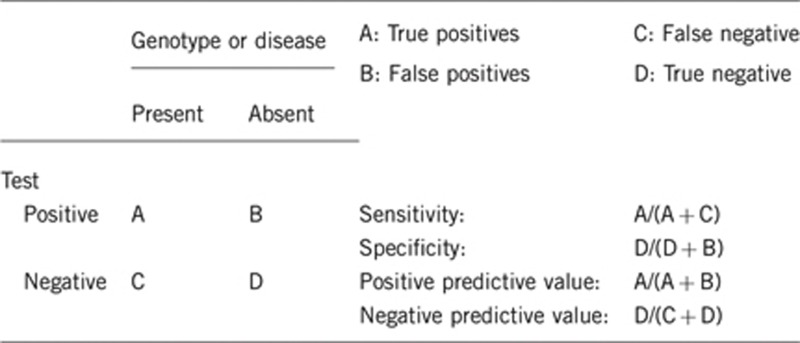

2.1 Analytical sensitivity

(proportion of positive tests if the genotype is present)

Nearly 100%. A test for large deletions/duplications in genes other than NPHP1 should be considered, especially in patients in whom a single heterozygous mutation has been detected with conventional sequencing. The presence of deep intronic mutations is not explored with current screening methods.

2.2 Analytical specificity

(proportion of negative tests if the genotype is not present)

Nearly 100%.

2.3 Clinical sensitivity

(proportion of positive tests if the disease is present)

The overall clinical sensitivity for JSRD can be estimated at about 50%, although a comprehensive mutation screening of all known genes in a cohort of JSRD patients has not been reported to date. It is expected that several disease causative genes still remain to be identified.

The clinical sensitivity can be dependent on variable factors, such as age or family history, and can be higher in selected clinical subgroups, based on existing gene–phenotype correlates. For instance, about the 75% of patients with JSRD and congenital liver fibrosis (including COACH syndrome) carry mutations in the TMEM67 gene and few additional patients are mutated either in RPGRIP1L or CC2D2A, raising the clinical sensitivity to >90% in this specific JSRD subgroup.

2.4 Clinical specificity

(proportion of negative tests if the disease is not present)

The clinical specificity is unknown, as a large number of patients with similar phenotypes (eg, cerebellar vermis hypoplasia without the MTS) have not been tested for mutations, and as mutations in JSRD-causative genes have been documented in patients with other conditions.

In particular, JSRD is allelic to the following disorders: Meckel syndrome, at ten gene loci (TMEM216, CEP290, TMEM67, RPGRIP1L, CC2D2A, TTC21B, CEP41, TMEM138, TCTN2, and TMEM231); Nephronophthisis and Senior-Løken syndrome, at four gene loci (NPHP1, CEP290, TMEM67, and RPGRIP1L); Leber Congenital Amaurosis, at one gene locus (CEP290); Oro-facio-digital type I syndrome, at one gene locus (OFD1).

2.5 Positive clinical predictive value

(life-time risk of developing the disease if the test is positive)

The penetrance of disease-associated mutations is 100%, with clinical variability. Multiorgan involvement, such as retinal, renal or hepatic disease, may develop at a later age (for instance, retinal dystrophy may present with congenital blindness or with progressive retinopathy; juvenile nephronophthisis usually becomes symptomatic towards the end of the first decade of life; congenital hepatic fibrosis is also progressive and may manifest at a variable age).

2.6 Negative clinical predictive value

(probability of not developing the disease if the test is negative)

Assume an increased risk based on family history for a non-affected person. Allelic and locus heterogeneity may need to be considered.

JSRD are congenital disorders, and the neurological phenotype associated to the brain malformation manifests either in the neonatal period (hypotonia, irregular breathing, nystagmus) or in the first year (developmental delay, oculomotor apraxia). A particular facial phenotype (open mouth, protruded tongue, high-arched eyebrows, anteverted nostrils) is commonly observed in infancy. Very rarely, mild phenotypes may remain undiagnosed for years.

Proband in that family had been tested:

If mutations with established pathogenic significance in a given gene have been detected in the proband, the probability for a relative (eg, a sibling) to develop the disease if the test is negative is negligible.

Proband in that family had not been tested:

If mutations with established pathogenic significance are not detected in the proband, the clinical predictive value of a negative genetic test is low (<50%), even if all known genes have been comprehensively screened, as not all JSRD causative genes are known. Nevertheless, a one in four recurrence risk in the future pregnancies should be assigned.

3. CLINICAL UTILITY

3.1 (Differential) diagnostics: The tested person is clinically affected

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘A' was marked)

3.1.1 Can a diagnosis be made other than through a genetic test?

3.1.2 Describe the burden of alternative diagnostic methods to the patient

Brain magnetic resonance imaging usually requires sedation or general anaesthesia in neonates and young children. Clinical diagnosis without brain imaging or genetic testing is non-specific in many patients.

3.1.3 How is the cost effectiveness of alternative diagnostic methods to be judged?

Brain magnetic resonance imaging is necessary and sufficient to make the diagnosis of JSRD, based on the identification of the ‘molar tooth sign'.

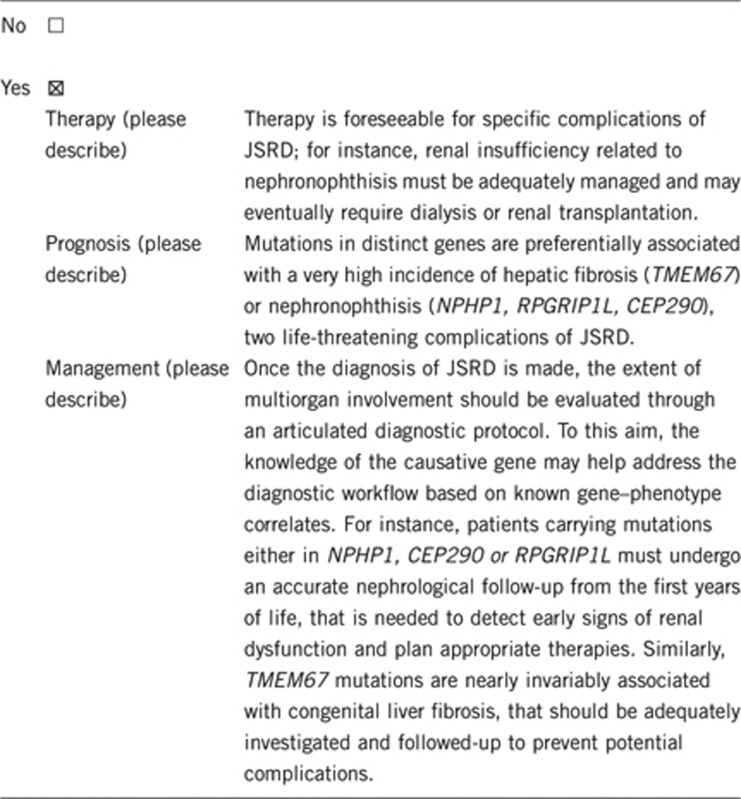

3.1.4 Will disease management be influenced by the result of a genetic test?

3.2 Predictive Setting: The tested person is clinically unaffected but carries an increased risk based on family history

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘B' was marked)

3.2.1 Will the result of a genetic test influence lifestyle and prevention?

If the test result is positive (please describe):

Not applicable.

If the test result is negative (please describe):

Not applicable.

3.2.2 Which options in view of lifestyle and prevention does a person at-risk have if no genetic test has been done (please describe)?

Not applicable.

3.3 Genetic risk assessment in family members of a diseased person

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘C' was marked)

3.3.1 Does the result of a genetic test resolve the genetic situation in that family?

Genetic testing of parents and healthy siblings may disclose whether they are heterozygous carriers of a pathogenic mutation. The detection of heterozygous mutations in both parents sets the recurrence risk for future pregnancies at 1 in 4, and enables prenatal diagnosis.

3.3.2 Can a genetic test in the index patient save genetic or other tests in family members?

No.

3.3.3 Does a positive genetic test result in the index patient enable a predictive test in a family member?

Identifying the causal mutations in the probands allows for carrier testing in parents and relatives.

3.4 Prenatal diagnosis

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘D' was marked)

3.4.1 Does a positive genetic test result in the index patient enable a prenatal diagnosis?

Yes. Prenatal diagnosis is feasible in families in which the causative mutations (according to autosomal recessive or X-linked inheritance) have been identified in the proband and confirmed in carrier parents. Prenatal imaging should be considered to confirm the genetic diagnosis, particularly with mutations that are of less certain pathogenicity (eg, missense).

4. IF APPLICABLE, FURTHER CONSEQUENCES OF TESTING

Please assume that the result of a genetic test has no immediate medical consequences. Is there any evidence that a genetic test is nevertheless useful for the patient or his/her relatives? (Please describe)

Confirmation of the diagnosis may end a diagnostic odyssey and helps avoiding additional unnecessary investigations and the stress of uncertainty for the family. Contact with appropriate patient organisation may prove helpful.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by EuroGentest, an EU-FP6 supported NoE, contract number 512148 (EuroGentest Unit 3: ‘Clinical genetics, community genetics and public health', Workpackage 3.2)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brancati F, Dallapiccola B, Valente EM. Joubert Syndrome and related disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:20. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Gleeson JG. The role of primary cilia in neuronal function. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;38:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi M, Glass I.Joubert Syndrome and Related Disorders: GeneReviews http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1325/ 9 July 2003 (Access date); Last Revision: 14 June 2012.

- Valente EM, Brancati F, Dallapiccola B. Genotypes and phenotypes of Joubert syndrome and related disorders. Eur J Med Genet. 2008;51:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]