Abstract

Understanding rational actions requires perspective taking both with respect to means and with respect to objectives. This study addresses the question of whether the two kinds of perspective taking develop simultaneously or in sequence. It is argued that evidence from competitive behavior is best suited for settling this issue. A total of 71 kindergarten children between 3 and 5 years of age participated in a competitive game of dice and were tested on two traditional false belief stories as well as on several control tasks (verbal intelligence, inhibitory control, and working memory). The frequency of competitive poaching moves in the game correlated with correct predictions of mistaken actions in the false belief task. Hierarchical linear regression after controlling for age and control variables showed that false belief understanding significantly predicted the amount of poaching moves. The results speak for an interrelated development of the capacity for “instrumental” and “telic” perspective taking. They are discussed in the light of teleology as opposed to theory use and simulation.

Keywords: Teleology, Desire, Theory of mind, Competition, Rationality, Reasons

Introduction

According to a time-honored view, explanations of intentional actions show the agent “in his role of Rational Animal” (Davidson, 1963). Intentional actions are inherently goal-directed. They are, in other words, intelligible in terms of what the agent regarded as an effective means to achieve some objective. To explain an intentional action in this way is to make rational sense of the action—to show it to have been a rational thing to do, at least in some minimal sense of “rationality.” As Davidson put it, “From the agent’s point of view there was, when he acted, something to be said for the action” (emphasis added pp. 691).

Now we can distinguish two ways in which the agent’s point of view may differ from that of the interpreter (someone seeking to understand why the agent did what she did). First, the interpreter may regard the means adopted by the agent as mistaken or suboptimal. Second, the interpreter might not share the agent’s objective, possibly (but not necessarily) because it is incompatible with his own objectives. Then, if the time-honored view is correct, understanding intentional actions would seem to require a basic form of perspective taking, both in relation to means and in relation to objectives. First, the interpreter needs to be able to explain an action in terms of the agent’s instrumental beliefs—beliefs he might not regard as correct. We call this ability “instrumental perspective taking.” For example, the interpreter needs to find it intelligible, in a standard false belief task, that in order to retrieve his chocolate, Max chooses to go to the blue cupboard owing to his false belief that this is where the chocolate is. Second, the interpreter needs to be able to explain an action in terms of a goal he does not share or does not take to be worthwhile. We call this ability “telic perspective taking.” There are, of course, a variety of reasons why an interpreter might not endorse the agent’s goal. Perhaps he thinks the goal reflects a mistaken instrumental belief about how to achieve some further goal (e.g., the agent may seek to open a certain bottle because she mistakenly believes it contains gin). Or, more interestingly, he may regard the proposed outcome as undesirable or bad (e.g., he may regard the agent’s having another glass of gin as undesirable because it would be harmful to her or because he would like to finish off the bottle himself). Again, of course, the interpreter might simply be indifferent to the agent’s enterprise.

A basic developmental question raised by this distinction is whether children acquire the capacity for perspective taking with respect to objectives and with respect to means at the same time. Three-year-olds are notoriously poor at predicting and explaining intentional actions in terms of mistaken instrumental beliefs—means falsely regarded by the agent as effective (Wellman, Cross, & Watson, 2001). But are they able to explain actions in terms of objectives they do not share? A stable finding in the development of belief–desire psychology is that in some ways young children find it easier to come to grips with desires than with beliefs. Thus, it is sometimes said that young children are “desire psychologists” before they acquire a “desire–belief psychology” (Bartsch & Wellman, 1995; Wellman, 1990). One might interpret this theory as holding that telic perspective taking precedes instrumental perspective taking. There are a number of extant findings that may seem to support this view—findings that are often thought to show that children understand the subjectivity of desires before they understand the subjectivity of beliefs (Rakoczy, 2010; Repacholi & Gopnik, 1997). Closer inspection, however, reveals that “appreciating the subjectivity of desires” can mean a number of things, not all of which involve telic perspective taking. On the specific issue of the development of instrumental and telic perspective taking, the extant evidence, we contend, is inconclusive. The aim of the current study was to present new evidence that directly speaks to that issue.

Perner, Zauner, and Sprung (2005, Fig. 11.4) reviewed several studies using three different paradigms that were considered as relevant in this context—wicked desires, conflicting desires, and competition—and their relation to performance on the false belief task. The results of these studies appeared to support the theory that there is a single capacity emerging that enables both instrumental and telic perspective taking at the same age (”unified perspective thesis”). Subsequent studies with these paradigms led to contradictory results. We look at these data more closely later in the Discussion. First, it is important to clarify when exactly understanding different desires requires telic perspective taking. This was not satisfactorily explained in Perner et al. (2005).

A clearer answer to this question has emerged from a reconceptualization of belief–desire psychology as “teleology-in-perspective” (Perner & Roessler, 2010). This was motivated by solving some foundational problems with the two dominant characterizations of folk psychology as a theory or as simulation. One motivation was to remind the field (pace theory theory) that folk psychology sees beliefs and desires not just as causes of behavior but also as reasons for acting (Anscombe, 1957; Davidson, 1963). With reference to the standard “Mistaken Max” false belief paradigm (Wimmer & Perner, 1983), where Max does not witness the unexpected transfer of his chocolate to a different location: on a causal view one can explain Max’s mistaken action by saying that circumstances cause him to have the false belief that his chocolate is still in its old place. Together with his desire to get to the chocolate, this belief causes him to go to the wrong location. This is treating the mind as a causal network on a par with physical causation. Gopnik and Meltzoff (1997) explicitly subscribed to such a picture.

In our understanding, folk psychology sees it differently. Max is not just driven to go to the wrong location but he has reasons to go there: wanting his chocolate, he has reasons to go where it is. He has a point of view on the matter. One strength of simulation theory is to capture the agent’s point of view. One pretends to have the same experiences as Max, and this supposedly triggers similar internal states. By introspection (Goldman, 1989; Goldman, 2006), one then discovers that these are a belief that the chocolate is still in its old place and an action tendency to go there. It is, however, intuitively not at all clear that we actually proceed in this way, and the existence of introspection of this kind has been a perennial problem (Carruthers, 2011; Gordon, 1995). Instead, Max’s point of view can be brought to the fore without taking on the theoretical burdens of simulation theory by teleology-in-perspective (Perner & Roessler, 2010). Reasons for action, in the most basic sense, are pairs not of mental states but rather of (typically nonpsychological) facts that count in favor of someone’s acting in a certain way—for example, the fact that it is desirable that Max should obtain his chocolate and the fact that he can do so by going to the place where the chocolate is. Practical deliberation is usually concerned with reasons in that sense. Now a simple-minded way to explain intentional actions would be to appeal to the reason-giving facts that causally explain the action. We call this “pure teleology.” (For a defense of the claim that such explanations could count as causal, and for some discussion of the relation between reasons and causes, see Perner & Roessler, 2010, section 5). This approach, of course, backfires in the false belief scenario because a mistaken agent will not go where he objectively should go. A more sophisticated interpreter appreciates that people act on the basis of what they take themselves to have reason to do, where this will reflect their beliefs about the world. To work out what Max will do, given his false belief, the interpreter needs to reason counterfactually: she needs to consider what Max would have reason to do if his belief were true (i.e., if the chocolate were still in its old location). This form of reasoning (which we call teleology-in-perspective) enables the interpreter to find Max’s action intelligible in terms of his perspective on his reasons without simulation—without needing to generate pretend beliefs and action tendencies within oneself and introspect on them, as simulation theory requires.

Now we can return to our question of what counts as evidence for children’s ability to engage in telic perspective taking. Pure teleology works on objective facts—an evaluative fact about a state that it is objectively worth achieving (needed, desirable, good, etc., which makes this state a goal) (e.g., that Max be with his chocolate) and objectively appropriate instrumental actions that achieve the goal (e.g., Max to walk where the chocolate is). The question is, what conditions—specifically relating to divergent goals—make this explanatory schema unworkable. Appreciation of competitive games is a good candidate.

In a competitive game, one’s moves serve not only to further one’s own goal but also do sabotage the opponent’s moves that further her goal. Suppose my chess partner can put me into checkmate on her next turn. To appreciate the significance of this fact, I need to recognize that from her perspective it is desirable that I should be checkmated. That, after all, is why she can be expected to make the move in question unless I can think of a way of protecting my king. So I need to find a way to bring about the (from my perspective) desirable goal of not being checkmated while simultaneously bearing in mind that from my opponent’s point of view it is desirable that I should be checkmated. Evidently, me being checkmated and me not being checkmated cannot both be objectively desirable without qualification. So the sophisticated teleologist needs to consider each goal under a different perspective. In contrast, a young teleologist who, by hypothesis, cannot consider different perspectives will therefore not find any sense or enjoyment in competitive games.

Consequently, the unified perspective thesis predicts that children who have no awareness of perspective (measured by not passing the false belief test) should find no pleasure in competitive games. Moreover, these two abilities should emerge in unison. In contrast, the desire-before-belief theory has no reason to assume that competitive games should not be appreciated before false beliefs, and it does not predict any relationship between these two abilities.

Sodian (1991) looked at children’s ability to sabotage as a contrast condition to their ability to deceive. Children found deception considerably more difficult than sabotage. In the two sabotage conditions, children needed to decide whether they wanted to lock a box with a treasure or leave it open when the robber came to steal the treasure (one-box trial) or whether they wanted to lock the empty box or the one with the treasure (two-box trial). They were told that they should not let the robber find the treasure. Importantly, this instruction already specified the robber’s action to be undermined, and so there was no need to infer this action from the robber’s goal. Preventing something by being explicitly told what to prevent should not cause a problem for the teleologist child. Indeed, most of the 3- to 5-year-olds chose the correct action (lock instead of leave open) or box (full instead of empty). Moreover, Sodian and Frith (1992) compared the same sabotage tasks with false belief attribution and found that for normal children sabotage was only slightly easier than the false belief task. Other studies using this paradigm (Hughes & Dunn, 1998; Hughes, Dunn, & White, 1998) did not report sabotage and deception separately. In sum, even if this sabotage task did require telic perspective taking, the reported differences are too small to speak against the unified perspective thesis.

There are also some data on children’s appreciation of competitive games. A venerable study by Gratch (1964; see also deVries, 1970) showed that the percentages of children showing competitive fervor in the good old penny hiding game (guessing in which hand a marble is hidden) increased from near zero to 100% between 3 to 6 years of age in a very similar fashion to corresponding percentages of children passing the false belief test in the later literature (Perner et al., 2005, Fig. 11.4). Although several other studies (Baron-Cohen, 1992; Chasiotis, Kiessling, Hofer, & Campos, 2006; Hughes & Dunn, 1998; Hughes et al., 1998) have used the penny hiding game in conjunction with the false belief test, they evaluated only children’s deceptive skills and not their competitive attitudes. The above-mentioned data seem to speak clearly in favor of a unified perspective thesis. Unfortunately, appreciation of the penny hiding game hinges not only on appreciating competition but also on understanding the consequences of information manipulation such as the false belief task. So we cannot be sure whether the reported correlations are due to what the theory predicts, namely a correlation between understanding false beliefs and appreciating competition, or due to both tasks depending on understanding the effects of information deprivation.

To get clearer evidence for a link between understanding false beliefs and appreciating competitive games, we adapted a competitive game that has no evident aspects of information manipulation or hiding like the penny game. Benenson, Nicholson, Waite, Roy, and Simpson (2001; see also Roy & Benenson, 2002; Weinberger & Stein, 2008) designed a game to investigate interference competition, in which one individual reduces another individual’s chances of gaining access to a resource (Roy & Benenson, 2002). This is a simple game of dice where each player needs to collect beads on a stick. The aim of the game is to be the first to reach a finish mark. Most important, the players are allowed to choose whether they want to take beads from the communal pile or from another player. Children’s competitive attitude is measured by the percentage of moves in which they take beads from another player (poaching move) and not from the communal depository. The goal of a poaching move, evidently, is to thwart the other player’s goal of reaching the top of the stack before the player making the poaching move. According to the unified perspective thesis, children who are not able to understand others’ perspectives cannot form the goal of thwarting an incompatible goal. A correlation between children’s performance on the false belief task and the amount of poaching moves in the bead collecting game, therefore, would support the unified perspective thesis. On the other hand, if the conventional view is correct and children are aware of the subjectivity of desires before they understand the subjectivity of beliefs (Wellman, 1990), there should be no correlation between poaching moves and false belief performance.

Method

Participants

A total of 86 children between the ages of 2;10 (years;months) and 5;10 (M = 4;3, SD = 8.9 months) from four different nursery schools in the city of Salzburg and two villages in Upper Austria volunteered for this study. Of this sample, 6 children did not want to come back for their second session (4 of them played the bead collecting game only, and therefore the number of playgroup members differs from the number of the final sample). Of the 28 game group triads, 3 needed to be excluded because of peculiar playing behavior of 1 participant in each group that strongly influenced the course of the game; of these participants, 1 child started to cry because another player took beads from her, 1 child monotonously took beads from the left neighbor without responding to the game itself, and 1 child continuously took beads from the best friend to please him. The remaining 25 playgroups consisted of 3 all-male triads, 2 all-female triads, 8 one-female/two-male triads, and 12 one-male/two-female triads. The final sample consisted of 35 girls (mean age = 4;4, SD = 8.7 months) and 36 boys (mean age = 4;3, SD = 9.5 months).

Design

Each child participated in both a game session within a group of three children and in an individual test session. The two sessions took place on the same day or on a later day but never more than 1 week later. Approximately half of the children participated first in the game and then in the individual test session and vice versa. The playgroup triads for the game were formed randomly among the children of each kindergarten class whose parents had agreed to let them participate in the study. Playing the game took between 5 and 10 min. The individual test sessions lasted approximately 15 min, and children were given five tasks in a completely randomized order. Each child completed a verbal intelligence test (Petermann, 2009), a visual working memory task (Daseking & Petermann, 2002), a phonological working memory task (Grimm, 2001), a day/night Stroop task (Gerstadt, Hong, & Diamond, 1994), and two false belief tasks (Wimmer & Perner, 1983).

Procedure and materials

Bead collecting game

The game was adapted from Benenson and colleagues (2001). In our version, we used three wooden stands with an upright stick, a basket with 50 wooden beads, and a large die with numbers of dots from 1 through 3. The game required the players to collect beads and thread them onto their vertical stand. Two female researchers accompanied three children at a time to a quiet room where the game materials were already positioned in a semicircle on a carpet on the floor. One experimenter sat down with the children, and for a first warm-up children were asked to pick a stand for playing the game and were invited to put three beads on their stand. After that, the experimenter explained the rules of the game in a standardized routine. She emphasized that the aim of the game was to fill the stand to the top as quickly as possible and that children could take the number of beads according to the number of dots on the die either from the community basket (“neutral move”) or from another player (“poaching move”). They were further told that the player who filled the stand first would be the winner of the game. A practice round was conducted, with each child being asked to repeat the game rules individually (“Where are you allowed to take beads from?” and “Can you tell me how you can win the game?”). In case of incorrect or incomplete answers, the rules were explained again until the child was able to answer both questions correctly (“the basket, Player 1, and Player 2” and “be the first whose stand is completely filled”, respectively). To make children constantly aware that there were two legitimate options of taking beads, each child was asked after every die throw whether she or he would like to take the beads from the basket or from another player’s stand. The second experimenter was seated on a chair some distance from the children where she could see the die and the three stands. For each individual move, the number on the die and the location from where the player took the beads were recorded.

False belief task

Two standard unexpected transfer false belief tasks (Wimmer & Perner, 1983) were administered. The picture stories were displayed on a laptop (PowerPoint) and narrated by the experimenter. Apart from different protagonists (female/male), toys (teddy/ball), siblings (brother/sister), and storage places (box/cupboard), the two versions were exactly the same. In the story, the protagonist briefly played with a toy and then put it in a storage place and left the room to have a drink or snack in the kitchen. Meanwhile, a sibling transferred the toy to a new container. At this point, children were asked three comprehension questions: “Where is the toy now?”, “Who placed it there?”, and “Where did the protagonist place the toy at first?” If a child gave an incorrect answer to one of the questions, the story was retold. No child needed more than one repetition before giving three correct responses. The story continued with the protagonist coming back and wanting to play with the toy again, and the prediction question was posed: “Where will he [she] first look for the toy?” Next, children were told that the protagonist would actually look in the empty location and were asked the explanation question: “Why did he [she] go there to get the toy?” Finally, two memory questions were asked to check whether answers to the test questions were not due to misremembering the story facts: “Where is the toy now?” and “Where did the protagonist place the toy at first?”

Control measures

To be able to check whether the correlation between game and false belief task is due to differences in intelligence, inhibitory control, or working memory, the following tasks were used.

Verbal intelligence test

The vocabulary subtest of the German version of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Third Edition (Petermann, 2009) consisted of 26 pictures of an object (e.g., car, fork, pineapple) that children needed to identify.

Day/night task

The procedure, instructions, and sequence of the Stroop-like task was administered following Gerstadt and colleagues (1994). After ascertaining that children associate a picture of a sun with daytime and a picture of a moon with nighttime, children were instructed to say “day” when shown the picture of the moon and to say “night” when shown the picture of the sun. If a child answered incorrectly in 2 practice trials, the instruction was repeated as often as necessary. The adjacent test consisted of 16 trials in a fixed random order, and no feedback was provided.

Working memory measures

As a measure for visual working memory capacity, we ran a subtest from a German battery of cognitive development tests (Daseking & Petermann, 2002). Children were shown 10 different objects (e.g., house, ball, baby) depicted on an A4-sized piece of paper (i.e., approximately 2 inches in size) with the instruction to remember as many objects as possible for later recall. After a 1-min learning phase (in which children were asked to name every object at least once so that the experimenter knew the terms the children used), children had 1.5 min (90 s) to recall the objects. Phonological working memory was assessed with a subtest from a German battery of language development tests (Grimm, 2001). Children needed to repeat the names (pseudowords) of 18 funny-looking little paper men who came out of a bag when called by their correct names. Pseudowords were presented in a fixed order and pronounced only once.

Results

Theory of mind

False belief prediction

Only 1 child gave a wrong answer to one of the five control questions. Performance on the two story versions (61% and 49% correct) did not differ significantly (McNemar’s χ2(1, N = 71) = 14.4, p = .115). For this and all subsequent calculations, two-tailed test results and exact p values are reported. Of the total sample, 29 children gave two correct predictions, 20 gave one correct prediction, and 22 gave no correct predictions.

False belief explanation

Children’s answers on the explanation test question were classified according to the following categories (see Perner, Lang, & Kloo, 2002): (1) mental state, 18 answers (e.g., “he thought it was in there,” “she doesn’t know it’s in the other box,” “he didn’t see it being moved”); (2) relevant story facts, 76 answers (e.g., “the other child put it in the new box,” “it was in here earlier”); (3) desire, 6 answers (e.g., “because he wants the ball”); (4) wrong location, 9 answers (e.g., “she should go over there”); (5) irrelevant facts, 5 answers (e.g., “he is silly,” “because he is wearing a blue jacket”); and (6) no or “don’t know,” 28 answers. In the case of multiple answers, the one that fit the highest category was used.

For further analysis, these categories were recoded as understanding (2 points for category 1 answers), transitional (1 point for category 2 answers), and no understanding (0 points for answers in categories 3–6). Explanations referring to the protagonist’s desire (category 3) were coded as incorrect because insisting on the agent’s desire to justify an erroneous action is uninformative (Wimmer & Mayringer, 1998). In contrast, relevant story facts (category 2) were scored as correct because even an adult might answer in this way as a shorthand indication of the causal source of the agent’s error. However, because it is not clear whether referring to a relevant story fact is a reliable indicator for false belief understanding, category 2 answers were coded as transitional answers.

Relating prediction and explanation

Taking both stories together, children could reach a total score ranging from 0 to 6 consisting of 0 to 2 points for correct predictions and 0 to 4 points for their explanations (explanation scores as defined above). Number of correct answers to the prediction (0–2) and explanation (0–4) questions were correlated, Spearman’s rho (71) = .44, p = .001. On the basis of the total score, the sample was divided into three groups, where 19 children (mean age = 48 months, 11 boys and 8 girls) reached a total score of 0 or 1 and were classified as non-understanders, 27 children (mean age = 49 months, 15 boys and 12 girls) reached a total score of 2 or 3 and were classified as transitionals, and 25 children (mean age = 57 months, 10 boys and 15 girls) reached a total score of 4 to 6 and were classified as understanders. As Amsterlaw and Wellman (2006) showed, understanding false beliefs is not an abrupt acquisition but rather undergoes an identifiable transitional period of acquisition. With our tripartite division of understanders–transitionals–non-understanders, we tried to capture these distinctions.

Bead collecting game

The number of rounds that were played in the 25 groups varied between 5 and 15 (M = 7.6), depending on the amount of poaching moves and on luck in casting the die. The majority of moves were neutral (74% beads taken out of the box) compared with poaching moves (26% beads taken from another player). The individual number of poaching moves varied between 0 and 14. Here, 25 children (35%, 8 girls and 17 boys) made no poaching move at all, and 17 children (24%, 14 girls and 3 boys) made only one such move. The remaining 29 children (41%, 13 girls and 16 boys) made more than one poaching move. For further analysis, the proportion of poaching moves to the total number of moves was used.

Control measures

Means and standard deviations of the four control tasks are reported in Table 1. Four children did not participate in the phonological working memory task because of either motivational (n = 1) or spelling (n = 3) problems, and one child refused to take part in the visual working memory task. Missing data were replaced by mean substitution (i.e., replacing values with the sample mean).

Table 1.

Correlations (Spearman’s rho) among false belief task, poaching moves, age, and control tasks.

| Mean% (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | .51⁎⁎⁎ | .51⁎⁎⁎ | .33⁎⁎ | .54⁎⁎⁎ | .45⁎⁎⁎ | .32⁎⁎ | .36⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| 1. | Poaching moves | .46⁎⁎⁎ | .17 | .34⁎⁎ | .08 | .12 | .13 | ||

| 2. | False belief prediction | 55.0 (42.4) | .44⁎⁎⁎ | .48⁎⁎⁎ | .36⁎⁎ | .38⁎⁎ | .28⁎ | ||

| 3. | False belief explanation | 39.4 (30.4) | .40⁎⁎⁎ | .28⁎ | .25⁎ | .24⁎ | |||

| 4. | Verbal intelligence | 72.6 (12.6) | .47⁎⁎⁎ | .52⁎⁎⁎ | .33⁎⁎ | ||||

| 5. | Inhibitory control | 71.1 (33.0) | .36⁎⁎ | .10 | |||||

| 6. | Phonological working memory | 60.4 (20.8) | .09 | ||||||

| 7. | Visual working memory | 61.7 (15.7) |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Relating false belief understanding to competition

A total of 42 children made either one or no poaching move, and therefore the assumptions of normality were not satisfied. A Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted to compare the proportion of poaching moves across the three false belief groups. There was a significant effect of groups, H(2) = 8.55, p = .014. Post hoc comparisons using Mann–Whitney test indicated that the median of the proportion of poaching moves was significantly higher for false belief understanders than for non-understanders, U = 115.0, z = −2.95, p = .003, r = −.45. However, the transitional group (Mdn = 16.67) did not differ significantly from either the false belief understanders (Mdn = 33.34) or the non-understanders (Mdn = 0.00), U = 254.5, z = −1.54, p = .124, r = −.21, and U = 195.5, z = −1.43, p = .152, r = −.21, respectively.

Furthermore, the correlation between false belief understanding and poaching moves was examined. Spearman’s rho revealed a statistically significant relation between false belief scores (0–6) and proportion of poaching moves, rs(71) = .36, p = .002. Table 1 shows that this correlation was mostly due to performance on the prediction task and displays all other relevant raw correlations. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was used to test whether performance on the false belief prediction task significantly predicted the proportion of poaching moves over and above age and control variables. Whereas age explained 26% of the variance, R2 = .26, F(1, 69) = 24.12, p = .000, control variables made no significant further contribution to explaining variance, R2 change = .05, F(4, 65) = 1.15, p = .34. However, when predictions in the false belief task were added as a predictor (β = .26, p = .036), the model improved significantly, R2 change = .046, F(1, 64) = 4.57, p = .036. Performance on the false belief task, therefore, explains variance in addition to age and cognitive abilities.

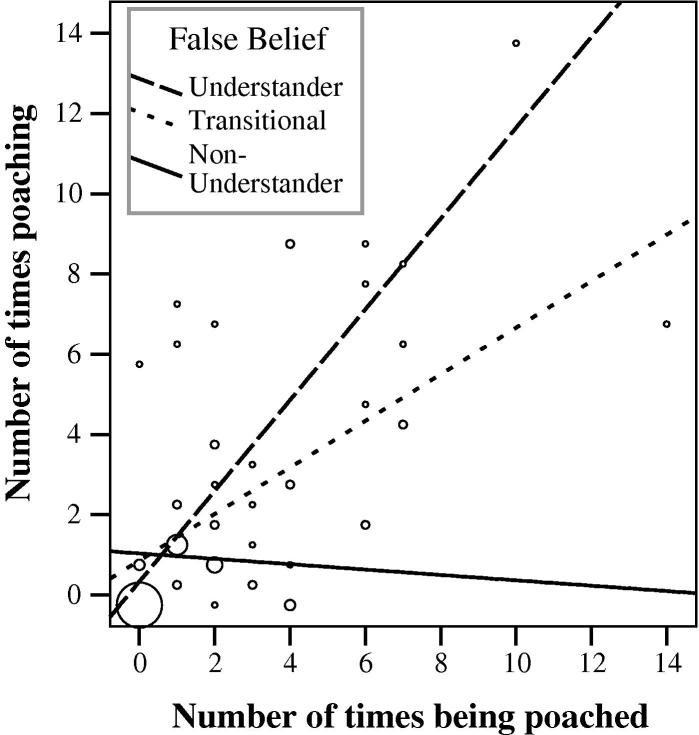

The experimenters noted that children’s tendency to take beads from their opponents varied not only with children’s understanding of false belief but also strongly with how often their opponents took beads from them. Indeed, the number of times a child suffered a poaching move and the number of times the child committed such a move were highly correlated, rs(71) = .64, p < .001. To gain a better understanding of how this relationship may be affected by children’s understanding of false beliefs, we regressed the number of poaching moves by the child on the number of times the child suffered a poaching move separately for each false belief group. The resulting regression lines are shown in Fig. 1. They are markedly different. Notably, only the understanders, β = .78, t(23) = 6.02, p < .001, and the transitionals, β = .62, t(25) = 3.90, p < .001, showed a positive slope. The children who did not understand false belief did not react in a retaliatory way to losing beads to others by taking beads from them, β = −.06, t(17) = −0.26, p = .797. This is very suggestive evidence that children without understanding of perspective, as assessed by the false belief test, don’t understand that the means to further the goal that their opponent gets more beads by taking some from them is incompatible with the goal of their getting more beads.

Fig. 1.

Regression lines for each false belief group depicting the relation between the number of poaching moves committed by the child and the number of poaching moves suffered by the child. Single data points can include one to four children. Exception: Data point 0–0 includes seven non-understanders, seven transitionals, and three understanders.

To address the question of whether the slopes of the three groups are significantly different, we compared the unstandardized beta coefficients by computing three individual two-sample t tests using the standard error of these coefficients for the error term. The results of the t tests indicated a significant difference among all three false belief groups. The slope of non-understanders was significantly different from the slopes of both understanders, t(42) = 3.86, p < .001, d = 1.18, and transitionals, t(44) = 2.33, p = .02, d = 0.70. There was also a significant difference between understanders and transitionals, t(50) = 2.32, p = .02, d = 0.64.

Gender differences

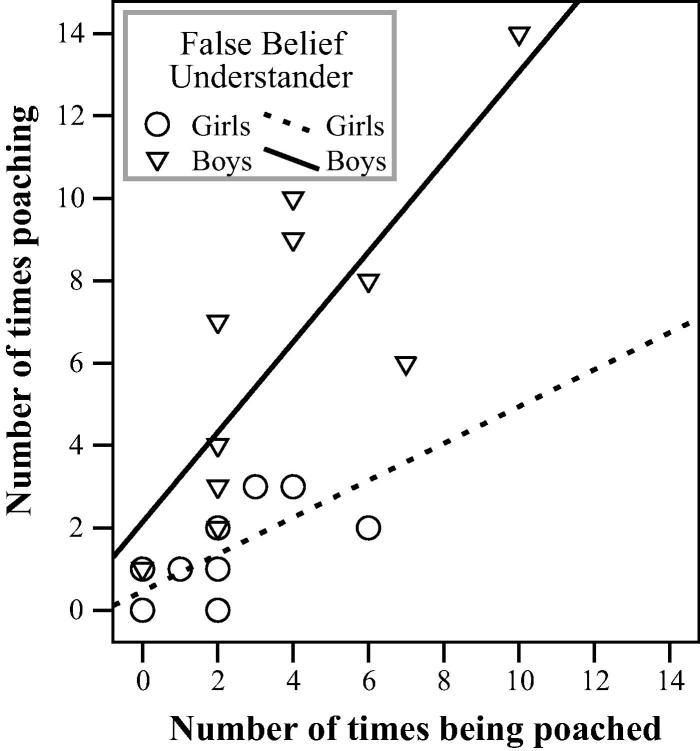

Benenson and colleagues (2001; see also Roy & Benenson, 2002; Weinberger & Stein, 2008) reported that boys were more competitive than girls. So we looked at whether these differences would be found in our study as well. Comparing the proportions of poaching moves between girls (Mdn = .17) and boys (Mdn = .14) did not show a significant difference. When looking at the three false belief groups separately, the only significant gender difference in the proportion of poaching moves was found in the group of understanders, U = 14.0, z = −3.40, p = .001, r = −.68. In this group, boys made significantly more poaching moves (Mdn = .60) than girls (Mdn = .20). Again we regressed the number of poaching moves by the child on the number of times the child suffered such a move for boys and girls in the group of false belief understanders. The regression lines of girls and boys are shown in Fig. 2. Although both girls and boys showed a significant positive slope, β = .74, t(13) = 3.99, p = .002, and β = .81, t(8) = 3.94, p = .004, respectively, the slopes (unstandardized beta coefficients) were significantly different, t(23) = −2,45, p = .022, d = 1.04. No other significant differences between boys and girls were found.

Fig. 2.

Regression lines for girls and boys in the false belief understander group depicting the relation between the number of poaching moves committed by the child and the number of poaching moves suffered by the child. Single data points can include one to three children.

Discussion

The main result of this study was that very few children who failed the false belief task showed any tendency to engage in competitive poaching moves. The paucity of such moves persisted even when these children suffered from their opponents’ poaching moves. This is a strong sign that these children cannot make sense of competitive behavior. In contrast, children who passed the false belief test engaged more often in competitive poaching moves, and this tendency was enhanced when they were subjected to such moves from others. Of course, not every child who understands competition necessarily engages in competition, and girls seemed to be more reluctant in this respect than boys. But this sex difference, which has been noted before (Benenson et al., 2001; Maccoby, 1990; Roy & Benenson, 2002), is limited to children who understand false beliefs.

This connection between understanding mistaken action in the false belief paradigm and competitiveness in a game shows that, contrary to Wellman (1990), desires are not generally understood before beliefs. Rather, when reasoning with desires requires telic perspective taking, it emerges at the same time as understanding mistaken actions due to a false belief, as hypothesized by Perner and Roessler (2010). They characterized the developmental changes at this age as a move from pure teleology that deals in objective facts and goals to teleology-in-perspective, which simultaneously provides for perspective taking with respect to means and ends.

To understand the impact of the current evidence in relation to earlier discussions of how false belief understanding is related to understanding desires, it is important to consider that not all seemingly relevant cases of “subjectivity” and of incompatible desires require awareness of perspective.

For instance, Repacholi and Gopnik (1997) found that as early as 18 months of age, children realize that a person who had shown a preference for broccoli over yummy crackers should be given broccoli when asking for something to eat rather than crackers that the children themselves clearly preferred over broccoli. Several other studies reflected on children’s abilities to predict preferences and provided similar data (e.g., Bartsch & Wellman, 1995; Rieffe, Terwogt, Koops, Stegge, & Oomen, 2001; Terwogt & Rieffe, 2003; Wright Cassidy et al., 2005). Although the children apparently understand that preferences can be subjective, the teleologist can, nevertheless, understand the action goals as objectively desirable without any need for telic perspective taking: a person who likes crackers should (objectively) be given crackers, and a person who likes broccoli should (objectively) be given broccoli. Consequently, preference differences of this kind pose no problem for the young teleologist who is unaware of the existence of perspective differences.

Moore, Jarrold, Russell, Sapp, and MacCallum (1995, Experiment 2) investigated understanding of incompatible goals, where children played in a puzzle competition against a puppet. On every turn, a card was drawn from the stack. If it fit into a player’s puzzle, that player could use it. At certain points in the game, the child and the puppet had conflicting needs; one was hoping for a blue card, and the other was hoping for a red card. Children were asked which card (red or blue) the puppet would want to come up next. Only approximately 35% of 3- and 4-year-olds correctly reported that the opponent would want a different color than what they needed for themselves. Furthermore, children’s performance on this task was as low as their performance on a false belief task. However, follow-up studies by Rakoczy, Warneken, and Tomasello (2007) and Rakoczy (2010) failed to show the results expected if children needed telic perspective taking for these tasks. Incompatible desire tasks were as easy as compatible desire tasks and were easier than false belief problems. For us, the fundamental question is why awareness of perspective should be necessary in these tasks. Note that correct answers to the test questions provide no evidence that children understand that the players are engaged in competition. Children merely need to understand that the puppet wants, say, a blue card to be drawn given, that this is what is needed to complete the puzzle the puppet is working on, not that the puppet wants a card to be drawn that will hinder completion of children’s own puzzle. The task does not require simultaneously making sense of actions pursuing conflicting goals, and a teleologist may simply not appreciate the competitive nature that we perceive in them.

Appreciation of incompatible goals has been reported in even younger infants. Behne, Carpenter, Call, and Tomasello (2005) found that 9-month-olds reacted with more impatience (banging and reaching) toward an adult who was unwilling to hand them a toy compared with an adult who was trying but unable to do so. These reactions may suggest that infants see the unwilling adult motivated by an opposing goal. However, the data can be easily accommodated within teleology. A child forms one global goal of “the toy should be given to me,” and the child’s reaction will be different when someone conforms to that goal and tries to do what should be done (give the child the toy) than when someone does not try to do so. In fact, teleology explains extremely well why children react with annoyance toward the unwilling. Obviously, when someone does not even try to do what should be done, one has good reason to be annoyed.

Another line of research suggests that 10- to 12-month-olds use social dominance representations to predict interactions between two agents in conflicting situations (Mascaro & Csibra, 2012; Thomsen, Frankenhuis, Ingold-Smith, & Carey, 2011). In Mascaro and Csibra’s (2012) study, infants first watched one of two animated object agents get its way in a conflict situation (wanting the same thing) and then expected the winner to prevail in a contextually different dominance contest thereafter (e.g., wanting to be in the same place). In Thomsen and colleagues’ (2011) study, infants predicted that a big agent would prevail over a smaller agent when their goals were conflicting. Children, however, need not see the interaction as one of conflicting goals. Recognizing that two agents are on collision course and anticipating the consequences or how the collision can be avoided does not show understanding of the conflicting goals that motivate these actions.

Research with even younger infants, 5- to 12-month-olds (Hamlin & Wynn, 2011; Hamlin, Wynn, & Bloom, 2007; Kuhlmeier, Wynn, & Bloom, 2003), demonstrated a preference for an agent who helped another agent to get on top of a hill (helper) over an agent who prevented the agent from succeeding (hinderer). Scarf, Imuta, Colombo, and Hayne (2012) reported that this preference may be largely due to a confounded feature (joyful jumping by primary agent after being helped but not after being prevented from succeeding). Yet even if the original preference due to helping can be re-established, it would not point to an understanding of goals beyond pure teleology. Infants can work on the basis of the objective goal that the primary agent should go to the top. Someone (or something) promoting this goal (the good) will be seen as better than someone (or something) impeding this goal. Thus, infants may develop a preference for the helper without understanding what the hinderer is doing in terms of an incompatible goal.

Incompatible goals also have been used for assessing the understanding of emotional consequences in older children (Perner et al., 2005). In one story, a boy and a girl sat in the same boat. The boy wanted to take the canal to the left, and the girl wanted to take the canal to the right. After they drifted to the right, children were asked to judge who was happier. In the control story, the boy and girl each sat in a boat but otherwise had the same preferences. Again both boats drifted into the right branch of the canal, and children were asked to judge who was happier. Answers in the first story were of equal difficulty and correlated with answers on a false belief test. Answers in the control story were somewhat better. Again follow-up studies by Rakoczy and colleagues (2007; see also Rakoczy, 2010) failed to replicate this pattern. However, it is important to note that these data do not speak to our question regarding telic perspective taking, since an awareness of perspectives is not required for correct answers. Children may pass such tests by relying on the following simple generalization:

If an agent wants a certain kind of event to happen, the agent will be happy if such an event happens and will be unhappy if it does not happen.

There is, in other words, no need to think of the agent’s emotional response as reflecting a judgment as to the desirability of a particular event. In this respect, the case of emotional reactions differs from that of intentional actions. To explain an action as an intentional action just is to think of it as performed for a reason, where this requires putting together an end (regarded as desirable) with a means (regarded as effective). Furthermore, in the action case, it is hard even to formulate analogous simple generalizations that are remotely plausible. Consider this proposal:

These tenets [of folk psychology] are perhaps best summarized by the “practical syllogism”: “If a psychological agent wants event y and believes that action x will cause event y, he will do x.” (Gopnik & Meltzoff, 1997, p. 126)

The problem is that this formulation cannot be directly used in a particular case. For instance, take Mistaken Max (discussed in the Introduction). From his experiential conditions, we can infer that he mistakenly believes his chocolate to be in its original place. We are told that he wants to get his chocolate. But we still do not know what Max believes about how to get to his chocolate. Naturally, we use our own general world knowledge to figure that out: Max going there would be the most obvious way, for all we know. It is often hard to see that such a piece of knowledge is missing because of its utter triviality. But it is easy to think of examples highlighting the gap. For instance, suppose that Max has been hospitalized and wants his chocolate. What will he do? We can give a sensible answer only if we know more about his particular circumstances and then figure out what the possible ways for him to get his chocolate would be (ask his mother to bring him the chocolate).

Tasks involving incompatible goals, therefore, denote a better test of telic perspective taking provided that simplifying strategies can be excluded. As a general rule, we need to exclude the possibility of considering the different goals separately. Cases of sabotage and competitive games do serve this purpose. Competition as a rational form of interaction is based on the combination of pursuing one’s own goal and at the same time of frustrating the opponent’s strategies based on his or her incompatible goal. Because the players’ goals are incompatible, they cannot be appreciated by a teleologist working within a single perspective.

Previous investigations of children’s appreciation of competition in the penny hiding game (Gratch, 1964) provided age-compatible results and even correlations with the false belief task (Baron-Cohen, 1992; Chasiotis et al., 2006; Hughes & Dunn, 1998; Hughes et al., 1998). Unfortunately, in this game, understanding competition is intrinsically mixed up with understanding the dependence of action on available information, which is also the central aspect of the false belief task. In contrast, moves in the bead collecting game are completely independent from the ability to decode the other players’ level of information. Thus, only the current study provides uncontaminated evidence that appreciation of competition codevelops with understanding beliefs.

One might question, however, whether success on the task requires meta-representing one’s own goal and one’s opponents’ goal. Might it not be possible to pass the task simply by forming the goal to achieve a certain physical state (having a full bead stand while the opponents’ stands are not full)?1 One question, of course, is why anyone would adopt that particular goal. “My bead stand should be full and the others’ stands should not” is hardly an intrinsically desirable state of affairs. On the face of it, it is the competitive context that turns it into an intelligible goal. But in any case, the current suggestion would leave unexplained why children do not always take beads from others, and why children who pass the false belief task tend to do so more than those who fail the false belief task. Although the younger children obviously were ambitious to fill their own bead stands, they did not seem to be concerned by the amount of beads on the opponents’ stands while playing. Only the older children (able to represent beliefs) took the other players’ scores into account.

There are other tasks that may seem to require telic perspective taking, including the sabotage task by Sodian (1991) that, unfortunately, is inconclusive for our purposes (as discussed in the Introduction). A quite different task that should be beyond the teleologist is the separation between goals and intentions (Shultz & Shamash, 1981; see reviews by Astington, 1999; Astington, 2001). Schult (2002) included children as young as 3 years. They needed to toss beanbags into different buckets, some of which contained a ticket for a prize. For each toss, children needed to indicate which bucket they intended to hit. On some trials they hit the intended bucket and on others they missed it, and on some trials they won a prize and on others they did not—resulting in four different combinations. The 4- and 5-year-olds were remarkably accurate in answering all types of questions. The 3-year-olds, on the other hand, had serious problems with questions about their intentions, in particular when satisfaction of their intentions contrasted with satisfaction of their desires. This difficulty is expected if 3-year-olds use teleology without perspective (Perner & Roessler, 2010, pp. 216–217). They know what they want, that is, winning the prize. They also understand intentions to hit a particular bucket, albeit only insofar as there are objective reasons for such intentions. Fortuitous success, where children accidentally get the prize after hitting a bucket they did not intend to hit, poses a problem. To understand that they did not intend to hit the bucket, children need to realize that they had no reason for hitting that particular bucket despite the fact that doing so turned out to be conducive to reaching their goal. A similar problem occurs in cases of bad luck, that is, where they hit the intended bucket without getting a prize. To understand that they hit the bucket intentionally, children need to understand that they did have a reason for hitting that bucket despite the fact that doing so turned out not to be conducive to reaching their goal. Correct judgment of these cases becomes possible only when one understands that one acted on the assumption that the prize might be in the bucket that one was aiming for. Because in the critical cases this assumption has turned out to be false, the intentionality of the intended action can be understood only if one can understand it in terms of the perspective of that assumption.

In sum, our results support the view that at around 4 years of age, children become able to see other people’s reasons for acting relative to these people’s perspective, both with respect to means and with respect to objectives. There are many tasks that require awareness of perspective that are mastered at this age and correlate with each other beyond general factors such as intelligence; examples include Level 2 perspective taking (Hamilton, Brindley, & Frith, 2009), appearance–reality distinction (Gopnik & Astington, 1988; Taylor & Carlson, 1997), interpreting ambiguous drawings (Doherty & Wimmer, 2005), understanding false direction signs (Leekam, Perner, Healey, & Sewell, 2008; Parkin, 1994; Sabbagh, Moses, & Shiverick, 2006), alternative naming (Doherty & Perner, 1998; Perner et al., 2002), episodic memory (Perner, Kloo, & Stöttinger, 2007; Perner & Ruffman, 1995), and understanding identity information (Perner, Mauer, & Hildenbrand, 2011). Their understanding of intentional action as acting for reasons follows this pattern. This is consistent with the theory proposed by Perner and Roessler (2010) that children understand people’s reasons at first in terms of teleology (objective reasons). With their growing awareness of perspective differences, children become able to use teleology within different perspectives. In this way, they can understand that someone may act rationally even when he or she uses ineffective means or pursues objectives they do not share.

This approach introduces a neglected element into “theory of mind” research, namely that we and our children do not primarily see people as being causally driven to certain behaviors by their desires and information conditions, as theory theory portrays it (Gopnik & Meltzoff, 1997), but that people act according to reasons (teleology) or what they take to be reasons from their perspective (teleology-in-perspective). This is akin to simulation theory in that interpretation requires perspective taking. However, unlike simulation, teleology-in-perspective does not essentially involve imaginative identification with others or recreating mental states in pretend mode (Goldman, 2006; Gordon, 1986).

Acknowledgments

We express our appreciation to the heads, as well as the parents and children, of the following kindergartens for their cooperation and valuable time in participating in this project: Kindergarten Höhnhart and St. Johann am Walde, Kindergruppe Europark, and Betriebskindergarten St. Johann–Spital. We thank Louisa Hacking for help with collecting data. This research was financially supported by Austrian Science Fund Project I637-G15, “Rule understanding, subjective preferences, and social display rules,” as part of the ESF EUROCORES Programme EuroUnderstanding initiative and forms part of the doctoral dissertation of Beate Priewasser in the Department of Psychology at the University of Salzburg.

Footnotes

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out this argument and are also grateful for many other valuable comments from the three reviewers that helped to improve the manuscript.

References

- Amsterlaw J., Wellman H.M. Theories of mind in transition: A microgenetic study of the development of false belief understanding. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2006;7:139–172. [Google Scholar]

- Anscombe G.M.E. Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 1957. Intentions. [Google Scholar]

- Astington J.W. The language of intention: Three ways of doing it. In: Zelazo P.D., Astington J.W., Olson D.R., editors. Developing theories of intention: Social understanding and self-control. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1999. pp. 295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Astington J.W. The paradox of intention: Assessing children’s metarepresentational understanding. In: Malle B.F., Moses L.J., Baldwin D.A., editors. Intentions and intentionality: Foundations of social cognition. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2001. pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S. Out of sight or out of mind? Another look at deception in autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33:1141–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch K., Wellman H.M. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1995. Children talk about the mind. [Google Scholar]

- Behne T., Carpenter M., Call J., Tomasello M. Unwilling versus unable: Infants’ understanding of intentional action. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:328–337. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benenson J., Nicholson C., Waite A., Roy R., Simpson A. The influence of group size on children’s competitive behavior. Child Development. 2001;72:921–928. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers P. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2011. The opacity of mind. [Google Scholar]

- Chasiotis A., Kiessling F., Hofer J., Campos D. Theory of mind and inhibitory control in three cultures: Conflict inhibition predicts false belief understanding in Germany, Costa Rica, and Cameroon. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2006;30:249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Daseking M., Petermann F. Hogrefe; Göttingen, Germany: 2002. Kognitiver Entwicklungstest für das Kindergartenalter (KET–KID) [Google Scholar]

- Davidson D. Actions, reasons, and causes. Journal of Philosophy. 1963;60:685–700. [Google Scholar]

- DeVries R. The development of role-taking as reflected by behavior of bright, average, and retarded children in a social guessing game. Child Development. 1970;41:759–770. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty M.J., Perner J. Metalinguistic awareness and theory of mind: Just two words for the same thing? Cognitive Development. 1998;13:279–305. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty M.J., Wimmer M. Children’s understanding of ambiguous figures: Which cognitive developments are necessary to experience reversal? Cognitive development. 2005;20:407–421. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstadt C.L., Hong Y.J., Diamond A. The relationship between cognition and action: Performance of children 3½–7 years old on a Stroop-like day–night test. Cognition. 1994;53:129–153. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman A.I. Interpretation psychologized. Mind and Language. 1989;4:161–185. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman A.I. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2006. Simulating minds: The philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience of mindreading. [Google Scholar]

- Gopnik A., Astington J.W. Children’s understanding of representational change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance–reality distinction. Child Development. 1988;59:26–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopnik A., Meltzoff A.N. A Bradford Book/MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1997. Words, thoughts, and theories. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R.M. Folk psychology as simulation. Mind and Language. 1986;1:158–171. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R.M. Simulation without introspection or inference from me to you. In: Davies M., Stone T., editors. Mental simulation: Evaluations and applications. Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 1995. pp. 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gratch G. Response alternation in children: A developmental study of orientations to uncertainty. Vita Humana. 1964;7:49–60. doi: 10.1159/000270053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm H. Hogrefe; Göttingen, Germany: 2001. Sprachentwicklungstest für Drei-bis Fünfjährige Kinder (SETK 3–5) [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton A.F., Brindley R., Frith U. Visual perspective taking impairment in children with autistic spectrum disorder. Cognition. 2009;113:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin K., Wynn K. Young infants prefer prosocial to antisocial others. Cognitive Development. 2011;26:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin K., Wynn K., Bloom P. Social evaluation by preverbal infants. Nature. 2007;450:557–560. doi: 10.1038/nature06288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C., Dunn J. Understanding mind and emotion: Longitudinal associations with mental-state talk between young friends. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1026–1037. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C., Dunn J., White A. Trick or treat? Uneven understanding of mind and emotion and executive dysfunction in “hard to manage” preschoolers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39:981–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmeier V., Wynn K., Bloom P. Attribution of dispositional states by 12-month-olds. Psychological Science. 2003;14:402–408. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leekam S., Perner J., Healey L., Sewell C. False signs and the non-specificity of theory of mind: Evidence that preschoolers have general difficulties in understanding representations. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2008;26:485–497. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E.E. Gender and relationships. American Psychologist. 1990;45:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascaro O., Csibra G. Representation of stable dominance relations by human infants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:6862–6867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113194109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C., Jarrold C., Russell J., Sapp F., MacCallum F. Conflicting desire and the child’s theory of mind. Cognitive Development. 1995;10:467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Parkin L.J. Unpublished thesis for doctoral degree; University of Sussex: 1994. Children’s understanding of misrepresentation. [Google Scholar]

- Perner J., Kloo D., Stöttinger E. Introspection and remembering. Synthese. 2007;159:253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Perner J., Lang B., Kloo D. Theory of mind and self-control: More than a common problem of inhibition. Child Development. 2002;73:752–767. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perner J., Mauer M.C., Hildenbrand M. Identity: Key to children’s understanding of belief. Science. 2011;333:474–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1201216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perner J., Roessler J. Teleology and causal reasoning in children’s theory of mind. In: Aguilar J., Buckareff A., editors. Causing human action: New perspectives on the causal theory of action. A Bradford Book/MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2010. pp. 199–228. [Google Scholar]

- Perner J., Ruffman T. Episodic memory an autonoetic consciousness: Developmental evidence and a theory of childhood amnesia. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1995;59:516–548. doi: 10.1006/jecp.1995.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perner J., Zauner P., Sprung M. What does “that” have to do with point of view? The case of conflicting desires and “want” in German. In: Astington J.W., Baird J., editors. Why language matters for theory of mind. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. pp. 220–244. [Google Scholar]

- Petermann F., editor. Wechsler preschool and primary scale of intelligence–III (WPPSI-III; Deutsche version) Pearson Assessment; Frankfurt am Main, Germany: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rakoczy H. Executive function and the development of belief–desire psychology. Developmental Science. 2010;13:648–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakoczy H., Warneken F., Tomasello M. “This way!”, “No! That way!”: 3-year-olds know that two people can have mutually incompatible desires. Cognitive Development. 2007;22:47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Repacholi B.M., Gopnik A. Early reasoning about desires: Evidence from 14- and 18-month-olds. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:12–21. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieffe C., Terwogt M.M., Koops W., Stegge H., Oomen A. Preschoolers’ appreciation of uncommon desires and subsequent emotions. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2001;19:259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Roy R., Benenson J.F. Sex and contextual effects on children’s use of interference competition. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:306–312. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh M.A., Moses L.J., Shiverick S. Executive functioning and preschoolers’ understanding of false beliefs, false photographs, and false signs. Child Development. 2006;77:1034–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarf D., Imuta K., Colombo M., Hayne H. Social evaluation or simple association? Simple associations may explain moral reasoning in infants. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schult C.A. Children’s understanding of the distinction between intentions and desires. Child Development. 2002;73:1727–1747. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz T.R., Shamash F. The child’s conception of intending act and consequence. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science. 1981;13:368–372. [Google Scholar]

- Sodian B. The development of deception in young children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1991;9:173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Sodian B., Frith U. Deception and sabotage in autistic, retarded, and normal children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33:591–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M., Carlson S.M. The relation between individual differences in fantasy and theory of mind. Child Development. 1997;68:436–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwogt M., Rieffe C. Stereotyped beliefs about desirability: Implications for characterizing the child’s theory of mind. New Ideas in Psychology. 2003;21:69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen L., Frankenhuis W.E., Ingold-Smith M.C., Carey S. Big and mighty: Preverbal infants mentally represent social dominance. Science. 2011;331:477–480. doi: 10.1126/science.1199198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger N., Stein K. Early competitive game playing in same- and mixed-gender peer groups. Merrill–Palmer Quarterly. 2008;54:499–514. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman H.M. A Bradford Book/MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1990. The child’s theory of mind. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman H.M., Cross D., Watson J. Meta-analysis of theory of mind development: The truth about false belief. Child Development. 2001;72:655–684. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer H., Mayringer H. False belief understanding in young children: Explanations do not develop before predictions. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1998;22:403–422. [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer H., Perner J. Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition. 1983;13:103–128. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(83)90004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright Cassidy K., Cosetti M., Jones R., Kelton E., Meier Rafal V., Richman L. Preschool children’s understanding of conflicting desires. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2005;6:427–454. [Google Scholar]