Abstract

We used data from Interactive Voice Response (IVR) self-management support studies in Honduras, Mexico, and the United States (US) to determine whether IVR calls to Spanish-speaking patients with chronic illnesses is a feasible strategy for improving monitoring and education between face-to-face visits. 268 patients with diabetes or hypertension participated in 6–12 weeks of weekly IVR follow-up. IVR calls emanated from US servers with connections via Voice over IP. More than half (54%) of patients enrolled with an informal caregiver who received automated feedback based on the patient’s assessments, and clinical staff received urgent alerts. Participants had on average 6.1 years of education, and 73% were women. After 2,443 person weeks of follow-up, patients completed 1,494 IVR assessments. Call completion rates were higher in the US (75%) than in Honduras (59%) or Mexico (61%; p<0.001). Patients participating with an informal caregiver were more likely to complete calls (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 1.53; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.04, 2.25) while patients reporting fair or poor health at enrollment were less likely (AOR:0.59; 95% CI: 0.38, 0.92). Satisfaction rates were high, with 98% of patients reporting that the system was easy to use, and 86% reporting that the calls helped them a great deal in managing their health problems. In summary, IVR self-management support is feasible among Spanish-speaking patients with chronic disease, including those living in less-developed countries. Voice over IP can be used to deliver IVR disease management services internationally; involving informal caregivers may increase patient engagement.

Introduction

A large body of evidence suggests that mobile health interventions (mHealth) including text messaging, Smartphone “apps,” and Interactive Voice Response (IVR) calls can improve the process and outcomes of chronic illness care.1–8 Because these services have the potential to increase patients’ access to health information between visits, mHealth may be particularly useful for patients with socioeconomic risk factors for poor outcomes due to inadequate engagement in medical care.9 While most studies of IVR self-management support have been conducted among English-speaking patients in the US, trials in other countries suggest that IVR and other mHealth services may improve chronic illness care in less developed parts of the world.5,7,8,10–12

Spanish-speaking Latino patients represent a particularly important focus for IVR interventions. Spanish-speakers in the United States (US) have high rates of: health literacy deficits,13 chronic disease,14 and economic barriers to treatment access.15 Limited English proficiency is a significant barrier to healthcare,13 and non-English-speaking patients often require more time and resources than their English-speaking counterparts. Spanish-speakers in Latin America have staggering rates of chronic illness, poverty, and illiteracy.16–18 Those challenges often are exacerbated by under-funded healthcare systems and geographic barriers to attending clinic visits for self-management education.

Research suggests that Spanish-speaking patients in the US can and will use IVR as part of their chronic illness care.19–23 Early studies showed that IVR reminders reduced return-visit failures for tuberculosis patients who spoke Spanish as well as other languages.24,25 In a trial of IVR self-management support for patients with diabetes, Spanish-speakers were more interested in accessing IVR health information than their English-speaking counterparts.21 Sarkar and colleagues found that US Spanish-speakers were interested in IVR support for chronic illness care,26,27 and IVR communication can yield higher contact rates than group medical visits for language minority groups.23

While these studies suggest that IVR may be a useful tool for chronic disease management among US-based Spanish-speakers, it is not known whether these benefits generalize to Spanish-speaking patients in other countries. In particular, information about Spanish-speaking patients’ engagement in IVR self-management support is limited, particularly for patients in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Evidence does suggest that this modality may be feasible; in a survey conducted in 2010, more than 70% of chronically-ill patients in Honduras had cell phone access and most were interested in receiving IVR support for their self-management.28

In the current study, we report data from more than 2,400 patient-weeks of IVR follow-up for patients with diabetes or hypertension in three countries: Honduras, Mexico, and the US. Our goal was to describe Spanish-speaking patients’ engagement in IVR calls and identify the predictors of more frequent completion of IVR monitoring and self-management support. We also examined patients’ satisfaction with IVR support and their perception regarding program benefits.

Methods

Overview

Data were collected as part of four IVR self-management support studies conducted among Spanish-speakers in Honduras, Mexico, and the US (under the umbrella known as the “CarePartner Program”). Each study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee at the University of Michigan and Ethics Committees in corresponding institutions in Honduras and Mexico.

Patients with diabetes or hypertension were identified by outpatient clinic records, clinician referral, or community outreach. Patients were excluded if they did not have access to a telephone or were not able to respond to weekly IVR calls due to cognitive or vision impairment, or mental illness. Eligible and interested patients completed written informed consent and baseline surveys. Details about recruitment and follow-up unique to each study are described below.

Participants received weekly IVR calls to their mobile or land-line telephones, with multiple call attempts at times that the patient indicated were convenient. Automated calls to patients in each country were made from US servers. Long distance calls were made via Voice over IP connections and Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) trunks serving the target areas. During the calls, patients reported information about their health status and self-care using their touch-tone key pad and received tailored self-management advice. IVR scripts used tree-structured algorithms to assess patients’ self-management behaviors, perceived health status, and symptoms. Both the diabetes and hypertension scripts focused on symptoms, diet, medication use, and home physiologic monitoring (i.e., glucose self-monitoring and home blood pressure monitoring). Call scripts were initially developed in English with input from experts in chronic disease management, primary care, and mHealth. Scripts were then professionally translated into Spanish, back translated into English for validation, and reviewed by local primary care providers for cultural appropriateness given the local dialect. Quality assurance testing was performed on all IVR programming, and website interface prototypes were evaluated by clinicians and convenience samples of patients in each location using free exploration and performance tests to ensure appropriate navigation and system utilization.29

Based on patients’ IVR-reported data, structured alerts were automatically sent via email to designated clinic representatives. Patients also had the option to participate with an informal caregiver, who received structured feedback via an IVR call or email based on the patient’s IVR reports. Caregiver feedback focused on the patient’s status, changes in health status, and what the caregiver could do to support the patient’s self-care. After the IVR calling period, patients were asked to complete an in-person or telephone follow-up survey including questions about their satisfaction with the IVR calls and the perceived impact of the service on their health and self-care.

Project-Specific Methods

Diabetes Patients in Honduras

This pilot study evaluated the feasibility and potential impact of IVR diabetes self-management support provided internationally using a cloud-computing model.11 Participants were enrolled between June and August 2010 from a community-based primary care clinic in Santa Cruz de Yojoa, Honduras. Diabetes patients were identified at the time of an outpatient clinic visit based on medical records and screening interviews. Patients completed an in-person baseline survey with the assistance of study staff, followed by six weeks of weekly IVR diabetes self-management support calls. Of the 93 patients who were found to be eligible, 86 (92%) enrolled in the study. A total of 56 patients (65%) completed post-intervention surveys. Sixty-two patients elected a family member or friend to participate with them, and those people received IVR feedback on their own mobile phones based on the patient’s IVR assessment calls. These participating informal caregivers are referred to below as the patient’s “CarePartner.”

Diabetes Patients in Monterrey, Mexico

This pilot randomized trial assessed the feasibility and potential impact of IVR self-management support among diabetes patients in Monterrey, Mexico. Patients were identified from three primary care clinics between January and March 2011 based on medical records and in-person screening interviews. Of the 123 patients who were found to be eligible, 62 (50%) enrolled in the study. Data presented here represent 31 patients randomly assigned to the intervention group, who received IVR calls for 12 weeks. Of the 31 patients who receive the IVR intervention, 24 (77%) completed post-intervention telephone surveys. Fifteen patients (48%) elected a family member or friend to participate with them and receive automated feedback based on the patient’s IVR calls.

Hypertension Patients in Honduras and Mexico

This randomized trial evaluated the impact of IVR self-management support plus home blood pressure monitoring among patients with uncontrolled hypertension.12 Between May and July 2011, adult patients with high blood pressures (i.e., systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg for non-diabetic patients and > 130 mmHg for diabetic patients) were identified from outpatient clinics in Cortéz, Honduras and Hidalgo, Mexico. Of 213 patients identified as eligible, 200 (94%) enrolled in the trial. Intervention patients received an electronic home blood pressure cuff and six weeks of weekly IVR monitoring and behavior change calls. Data presented here represent 100 patients randomized to receive the intervention plus an additional 28 control group patients in Honduras who opted to receive IVR support calls after completing their trial participation. Forty-one intervention-group patients in Honduras (82%) and 46 in Mexico (92%) completed follow-up surveys. Thirty-one patients in Honduras and 13 patients in Mexico chose to participate with an informal caregiver who received feedback based on the patients’ IVR calls.

Diabetes Patients in the US

This pilot study determined the feasibility of IVR monitoring and self-management support among monolingual Spanish speakers receiving care in community-based primary care clinics in Michigan. Between May 2009 and September 2011, 42 patients were referred to the study by staff in six community clinics and were found to be eligible via telephone screening. Twenty three patients (55%) enrolled and received weekly IVR calls for 12 weeks. All patients completed follow-up surveys, and all enrolled with a family member or friend who participated as their CarePartner.

Data Collection and Analysis

Each IVR system automatically captured data on the calling process, including the date and time of each call attempt. For the current study, we created a dataset including one record representing each patient-week of follow-up, with an indicator for whether or not the patient completed that week’s call. Additional patient-level information was compiled from baseline patient surveys, including patients’ sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, and years of education) and health status (measured by the SF-12 mental- and physical composite summary scores30).

A total of 71% of all participants completed follow-up surveys, and these data were used to examine patients’ satisfaction with the IVR self-care support. There was no difference between those completing and not completing follow-up surveys in terms of patients’ baseline perceived health status, disease (i.e., diabetes versus hypertension), age, or gender. Follow-up survey completion varied across countries, with 100% of US patients completing follow-ups, compared to 59% of patients in Honduras and 86% in Mexico (p<0.001). Patients who participated with an informal caregiver or CarePartner were more likely to complete follow-up surveys than patients who participated alone (78% versus 62%, p=0.006).

Our main outcome of interest was completion of the IVR assessment and self-care support call during each week of participation. In initial analyses, we examined variation in patient characteristics across programs and countries. Multivariate regression models adjusting for the clustering of outcome weeks by patient were used to identify the predictors of whether or not a weekly IVR assessment was completed. Patient-level predictors included patient characteristics (age, gender, years of education, diagnosis, country, and baseline perceived health status) and participation with an informal caregiver (yes versus no). Models also included a time-varying covariate indicating the elapsed time between the patient’s date of enrollment in the program and the call week.

Based on model coefficients, we computed predicted probabilities of call completion over time for the overall sample, and then based on models with the same coefficients computed separately by country. Trends in call completion across weeks and 95% confidence bands were computed using the prgen routine in Stata v11. For those computations, other patient characteristics were set to the distribution average. In order to detect any non-linear relationship between patient age and the likelihood of completing calls, we refit the multivariable logistic model using the same coefficients but using cubic splines with four knots to detect non-linear age effects. We used bivariate analyses and a multivariate model to identify potential patient characteristics associated with the choice to participate with a CarePartner. Cross tabulations were used to examine patients’ satisfaction with the IVR intervention.

Results

A total of 268 patients received IVR calls, including 164 patients in Honduras, 81 patients in Mexico, and 23 patients in the US (Table 1). Roughly half (48%) of participants had hypertension and 52% had diabetes. On average patients were 55 years of age, and 73% were women. Patients had an average of six years of education; education was highest in the US subsample and lowest among patients in Honduras. Most patients reported fair or poor health at baseline. Over half (54%) participated with an informal caregiver or CarePartner.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Unadjusted Call Completion Rates

| Total | HON-HTN | HON-DM | MEX-HTN | MEX-DM | USA-DM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (N) | 268 | 78 | 86 | 50 | 31 | 23 |

| Mean Age in Years (SD) | 55.1 (11.8) | 55.3 (10.9) | 54.7 (10.8) | 61.3 (11.6) | 54.0 (11.8) | 44.6 (11.7) |

| Female (%) | 72.8 | 79.5 | 70.9 | 62.0 | 77.4 | 73.9 |

| Mean Yrs of Ed (SD) | 6.1 (4.4) | 5.6 (4.4) | 4.8 (4.1) | 6.7 (4.5) | 6.8 (4.0) | 10.3 (2.1) |

| Fair/Poor Health (%) | 75.8 | 80.8 | 8.2 | 88.0 | 48.4 | 52.2 |

| CarePartner (%) | 53.7 | 39.7 | 72.1 | 26.0 | 48.4 | 100.0 |

| N (call weeks) | 2,443 | 917 | 575 | 314 | 368 | 269 |

| Median Follow-up (Q-Q) | 7 (7,12) | 11 (9,16) | 7 (7,7) | 6 (6,6) | 12 (12,12) | 12 (12,12) |

| N (Completed Assessments) | 1,494 | 652 | 224 | 179 | 237 | 202 |

| Assessments Completed (%) | 61.2 | 71.1 | 39.0 | 57.0 | 64.4 | 75.1 |

Notes: HON-HTN: hypertension patients in Honduras; HON-DM: diabetes patients on Honduras; MEX-HTN: hypertension patients in Mexico; MEX-DM: diabetes patients in Mexico; US-DM: diabetes patients in the United States. SD = standard deviation. CarePartner: patient elected to participate with a friend or family member who received automated feedback based on the patient’s IVR reports. Q-Q = interquartile range.

Patients completed a total of 1,494 weekly IVR calls over 2,443 calling weeks, for an average call completion rate of 61% (Table 1). Call completion rates were highest among US patients with diabetes (75%) and lowest among diabetes patients in Honduras (39%). In multivariate models adjusting for clustering of outcome weeks and patient characteristics (Table 2), the adjusted odds of completing an IVR assessment was 2.35 times higher in the US than in Honduras, with patients in Mexico having intermediate call completion rates. Having a diagnosis of diabetes was associated with a significantly lower odds of call completion. Compared to patients under age 55, call completion rates were at least as high among patients ages 55–64, although significantly lower among patients ages 65+ (AOR=0.48, CI: 0.29, 0.78). Call completion rates were significantly lower among patients who reported fair or poor health status at the time of enrollment. Patients who participated with an informal caregiver had significantly greater odds of completing their IVR calls than patients who participated alone (AOR= 1.54; CI: 1.05, 2.25).

Table 2.

Predictors of Call Completion from Multivariable Regression Model

| AOR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| USA (a) | 2.35 | 1.19, 4.64 | 0.01 |

| Mexico (a) | 1.27 | 0.81, 1.98 | 0.30 |

| Diabetes (b) | 0.33 | 0.23, 0.49 | <0.001 |

| Age 55–64 Years(c) | 1.35 | 0.85, 2.13 | 0.20 |

| Age 65+ Years(c) | 0.48 | 0.29, 0.78 | 0.003 |

| Male | 0.92 | 0.62, 1.36 | 0.66 |

| Years of Education | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.08 | 0.32 |

| Fair/Poor Health (d) | 0.59 | 0.38, 0.92 | 0.02 |

| CarePartner | 1.54 | 1.05, 2.25 | 0.03 |

| Call Week | 0.98 | 0.95, 1.02 | 0.33 |

Notes: AOR = adjusted odds ratio. CI = confidence interval. (a) referent: Honduras; (b) referent: hypertension; (c) referent: age less than 55 years; (d) referent: good/excellent health.

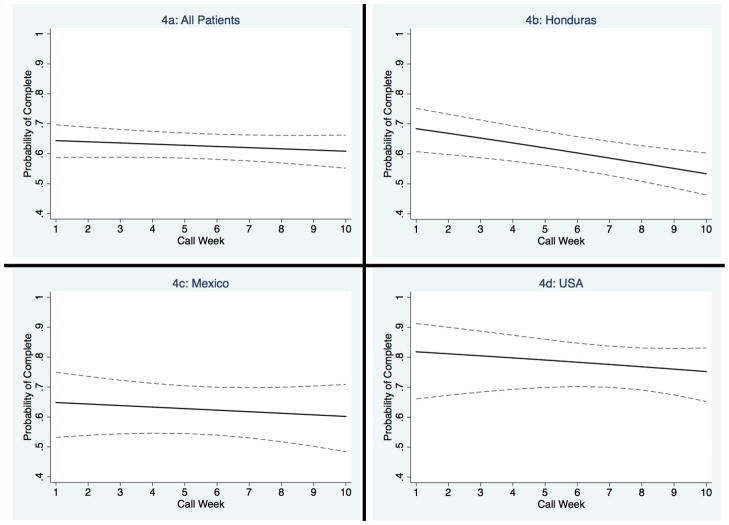

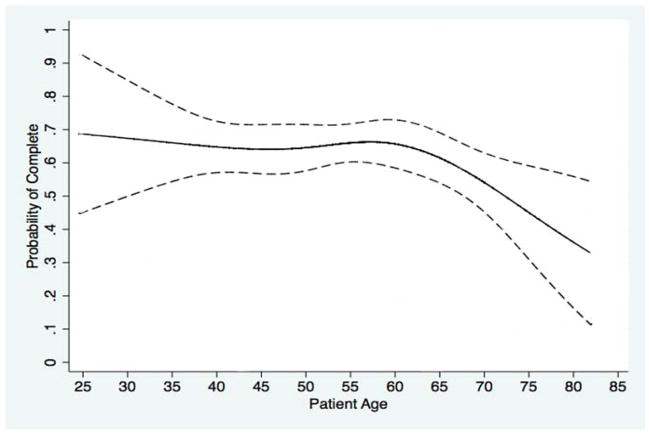

Variation in call completion rates across countries and over time is illustrated in the Figure 1. Honduras was the only country with a statistically significant decrease in call completion rates over time, and predicted call completion rates dropped close to 50% in that country by 10 weeks. Smaller and statistically non-significant decreases in call completion rates were observed in Mexico and the US, with the US patients having predicted call completion rates over 70% throughout their participation. As shown in Figure 2, call completion rates remained constant across ages until roughly 62 years, and then dropped off significantly among older patients.

Figure 1.

Probability of Call Completion by Country Predicted from Mutivariable Logistic Regression Models

Figure 2.

Probability of Call Completion by Patient Age

Satisfaction rates were high across programs (Table 3), with 88% of all patients who completed follow-up surveys reporting that they were “very satisfied” and 11% reporting that they were “mostly satisfied.” All patients (100%) reported that the information provided in the IVR calls was helpful and, despite patients’ limited educational attainment, 98% reported that the automated calls were easy to use. Patients reported that the program was helpful in managing their chronic disease, with 86% of all patients reporting that the programs helped them “a great deal.” With regard to specific behaviors, 77% of all patients reported that their diet improved “a great deal” as a result of the intervention, 80% reported that their symptom monitoring improved “a great deal,” and 80% reported that their medication adherence improved “a great deal.” Overall satisfaction rates were lower among US patients than among patients in Honduras and Mexico. Because satisfaction rates tended to be uniformly high, multivariate models did not identify meaningful predictors of satisfaction across patient subgroups.

Table 3.

Satisfaction with IVR Self-Management Support Calls

| Total | HON-HTN | HON-DM | MEX-HTN | MEX-DM | USA-DM | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How satisfied are you with the program? | 0.04 | ||||||

| Very satisfied | 87.8 | 92.7 | 87.3 | 93.6 | 91.3 | 65.2 | |

| Mostly satisfied | 10.6 | 4.9 | 12.7 | 4.3 | 8.7 | 30.4 | |

| Did the program help you deal more effectively with your health problem? | 0.15 | ||||||

| Yes, a great deal | 85.8 | 90.2 | 76.4 | 91.5 | 91.7 | 82.6 | |

| Yes, somewhat | 13.2 | 9.8 | 23.6 | 6.4 | 8.3 | 13.0 | |

| My diet improved “a lot” | 76.5 | 85.4 | 74.6 | 75.0 | 82.6 | 60.9 | 0.24 |

| My symptom monitoring improved “a lot” | 75.2 | 78.1 | 63.0 | 75.0 | 95.8 | 78.3 | 0.04 |

| My medication adherence improved “a lot” | 79.6 | 80.5 | 76.5 | 63.2 | 95.8 | 81.8 | 0.11 |

| The automated calls were easy to use | 97.8 | 100.0 | 94.6 | 100.0 | 95.8 | 100.0 | 0.25 |

| The information provided was helpful | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 1.0 |

Notes: Cell entries are column percents. HON-HTN: hypertension patients in Honduras; HON-DM: diabetes patients in Honduras; MEX-HTN: hypertension patients in Mexico; MEX-DM: diabetes patients in Mexico; US-DM: diabetes patients in the United States. CarePartner: patient elected to participate with a friend or family member who received automated feedback based on the patient’s IVR reports. Q-Q = interquartile range.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to examine engagement and satisfaction with IVR disease management calls among Spanish-speakers, and, to our knowledge, the first study to do so with a sample of patients in three countries, including two LMICs. Overall, we found that IVR self-management support was feasible cross-nationally, and that satisfaction levels were universally high among patients, including those with low levels of educational attainment.

Variation in call completion rates across countries likely result from both patient factors and system-related challenges. Patients in Honduras and Mexico had less familiarity with IVR and faced multiple challenges to answering IVR calls. Calls to Honduras and Mexico were made from US servers using Voice over IP (VoIP) connections, and extreme weather or other technical challenges caused occasional outages that either delayed or prevented calls from going through to patients’ phones. VoIP calls require purchasing services from Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) trunk providers, and the geographic location of those providers can have an important effect on service reliability. Further work is needed to identify the improvements that will be necessary for ongoing patient monitoring and self-management support via IVR in low income countries. Servers located within countries or at least closer to the target population should reduce technical problems and improve call completion rates.

Despite technical challenges, the current study demonstrates that IVR self-management support can substantially increase chronically-ill Spanish-speakers’ access to health information, even among those living in LMICs. While lower call completion rates in LMICs are a concern, IVR still offers more support than patients otherwise would have available through their local provider. It is worth noting that this added support comes at little cost to the provider organization or the patient. The cloud computing approach used to generate calls to Honduras and Mexico demonstrates that national or international programs could be developed to provide mHealth services to resource-limited areas via centralized servers and relationships with regional Internet service providers. Moreover, it may be that patients in countries such as Honduras will benefit disproportionately from even less frequent calls, given that those patients face greater challenges to accessing chronic disease management services. Further studies may need to explore what factors unique to each population would improve participation rates and prevent drop out.

The higher satisfaction rates among Honduran and Mexican patients may reflect the fact that the relatively limited access to chronic illness care in those countries meant that even less frequent IVR calls could have a significant impact. Moreover, outcomes from the hypertension study in Honduras and Mexico suggest that despite lower call completion rates, those patients benefited from the IVR calls with respect to their self-care behaviors, perceived health status, and physiologic outcomes.12

We identified several factors associated with variation in patients’ call completion rates, as well as other factors that were not associated with variation in patients’ likelihood of completing their IVR calls. Call completion rates varied across age groups, and were higher among patients less than sixty-five years of age. Older Spanish-speaking Latino patients may have less immediate access to a mobile phone which is shared with adult children and other social network members who are more likely to carry the device with them. Moreover, older patients may be particularly vulnerable to interruptions in telephone service during periods when they cannot afford the cost. Call completion rates were lower among patients who reported fair or poor health status at study entry, and more research is needed to identify the barriers to IVR monitoring and self-care support for this important, high-risk group. Importantly, calls were equally likely to be completed by women and men and did not vary by educational attainment, suggesting that IVR could be used to target patients with low health literacy who need more frequent monitoring and targeted information about their self-care.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to demonstrate that patients for whom family caregivers received regular feedback based on their self-management calls had higher call completion rates. In a yet-to-be-published study of similar data from more than a thousand English-speaking patients in the US, we also found that patients participating in IVR programs with CarePartners had higher call completion rates. Exploratory analyses in the current study did not identify baseline demographic or clinical characteristics associated with opting for participation with a CarePartner, suggesting that the “caregiver effect” is likely causal. Particularly among Latino patients with strong social bonds, investigators and program developers should continue to explore how to maximize the benefits of caregiver participation – for increasing both patient engagement as well as the benefits of mHealth self-management support information.

The current study has several limitations. Although it represents more than 2,400 person-weeks of follow-up (i.e., 46 person-years of observation) individual patients participated for only six to 12 weeks. Longer-term studies of IVR program engagement will be important, particularly since the current data suggest that in some populations call completion rates may decline over time. As noted earlier, randomized outcome data for hypertensive patients in Mexico and Honduras suggest that patients can achieve important outcomes even when call completion rates are less than 70%,12 and future studies should seek to determine the optimal frequency of contact with IVR. Also as noted above, we were not able to measure the role of telephone outages and other communication system challenges as determinants of missed calls in Honduras and Mexico. Satisfaction rates and patients’ perceptions regarding the benefits of IVR self-management reports were positive, although we cannot determine the extent to which social desirability led patients to over-estimate the service’s benefits. Similarly, patients’ improvements in diet and other self-care behaviors were self-reported and not verified through objective clinical measures.

In conclusion, we found that IVR self-management support was feasible among Spanish-speaking patients with diabetes or hypertension in these three countries, and that the service resulted in high levels of patient satisfaction and perceived benefit. Although call completion rates were lower in Honduras and Mexico than in the US, the current study demonstrates that mHealth services such as IVR can be delivered to patients in LMICs across long distances, using a cloud-computing approach and a centralized server to reach patients in areas with limited telecommunication infrastructure. Feedback based on IVR reports to patients’ informal caregivers may increase engagement in these programs. More generally, IVR self-management support may be a feasible way to increase chronically ill patients’ access to monitoring and self-care information, both among Spanish-speakers in the US as well as in Latin America.

Footnotes

Declarations: John Piette is a VA Senior Research Career Scientist. Studies described here were supported by grant number P30DK092926 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Additional support was provided by the University of Michigan Global REACH Program, Center for Global Health, and School of Public Health; and by the Center for Healthcare Research and Transformation. Financial support for the Diabetes pilot study in Monterey, Mexico, was provided by the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Mexico. Home blood pressure monitors were donated by OMRON™. None of the authors has any conflict of interest associated with this submission. All authors meet all three of the criteria for authorship as stated in the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals.

References

- 1.Wei J, Hollin I, Kachnowski S. A review of the use of mobile phone text messaging in clinical and healthy behavior interventions. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2011;17:41–48. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.100322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2010;32(1):56–69. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fjeldsoe B, Marshall AL, Miller YD. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-messaging service. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liew S-M, Tong SF, Lee VKM, Ng CJ, Leong KC, Teng CL. Text messaging reminders to reduce non-attendance in chronic disease follow-up: a clinical trial. British Journal of General Practice. 2009;59:916–920. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X472250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zurovac D, Sudoi RK, Akhwale WS, et al. The effect of mobile phone text-message reminders on Kenyan health workers’ adherence to malaria treatment guidelines: a cluster randomised trial. The Lancet. 2011;378(9793):795–803. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60783-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Free C, Knight R, Robertson S, et al. Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): a single-blind, randomised trial. The Lancet. 2011;378:49–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60701-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deglise C, Suggs LS, Odermatt P. Short Message Service (SMS) applications for disease prevention in developing countries. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2012;14(1):e3. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1823. + [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horvath T, Azman H, Kennedy GE, Rutherford GW. Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients wtih HIV infection (review) 3. The Cohcrane Collaboration Library; 2012. www.thecochranelibrary.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piette JD, Moura LA, Fraser HS, Mechael PN, Powell J, Khoja SR. Impacts of e-health on the outcomes of care in low- and middle-income countries: where do we go from here? WHO Bulletin. 2012;90:365–372. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.099069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swinfen R, Swinfen P. Low-cost telemedicine in the developing world. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2002;8(Suppl 3 6):63–65. doi: 10.1258/13576330260440899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piette JD, Mendoza-Avelares MO, Ganser M, Mohamed M, Marinec N, Krishnan S. A preliminary study of a cloud-computing model for chronic illness self-care support in an underdeveloped country. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;40(6):629–632. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piette JD, Datwani H, Gaudioso S, et al. Hypertension management using mobile technology and home blood pressure monitoring: results of a randomized trial in two low/middle income countries. Telemedicine and e-Health. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2011.0271. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leyva M, Sharif I, Ozuah PO. Health literacy among Spanish-speaking Latino parents with limited English proficiency. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2005;5(1):56–59. doi: 10.1367/A04-093R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DEH. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ku L, Matani S. Left out: Immigrants’ access to health care and insurance. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(1):247–256. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. 2010 http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789240686458_eng.pdf.

- 17.Alwan A, MacLeary DR. A review of non-communicable disease in low- and middle-income countries. International Health. 2009;1(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.inhe.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miranda JJ, Kinra S, Casas JP, Smith GD, Ebrahim S. Non-communicable disesaes in low- and middle-income countries: context determinants, and health policy. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2008;13(10):1225–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brodey BB, Rosen CS, Brodey IS, Sheetz B, Unutzer J. Reliability and acceptability of automated telephone surveys among Spanish- and English-speaking mental health services recipients. Ment Health Serv Res Sep. 2005;7(3):181–184. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-5786-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorig K, Ritter PL, Villa F, Piette JD. Spanish diabetes self-management with and without automated telephone reinforcement: two randomized trials. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(3):408–414. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piette JD. Patient education via automated calls: a study of English- and Spanish-speakers with diabetes. Am J Prev Med. 1999;17(2):138–141. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piette JD, McPhee SJ, Weinberger M, Mah CA, Kraemer FB. Use of automated telephone disease management calls in an ethnically diverse sample of low-income patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(8):1302–1309. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.8.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schillinger D, Hammer H, Wang F, et al. Seeing in 3-D: Examining the reach of diabetes self-manament support strategies in a public health care system. Health Education and Behavior. 2008;35(5):664–682. doi: 10.1177/1090198106296772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanke ED, Leirer VO. Automated telephone reminders in tuberculosis care. Med Care. 1994;32:380–389. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199404000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanke ED, Martinez CM, Leirer VO. Use of automated reminders for tuberculin skin test return. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1997;13(3):189–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarkar U, Piette JD, Gonzales R, et al. Preferences for self-management support: findings from a survey of diabetes patients in safety-net health systems. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarkar U, Handley MA, Gupta R, et al. Use of an interactive, telephone-based, self-management support program to identify adverse events among ambulatory diabetes patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;23(4):459–465. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0398-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piette JD, Mendoza-Avelares M, Milton EC, et al. Access to mobile communication technology and willingness to participate in automated telemedicine calls among chronically-ill patients in Honduras. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2010;16(10):1030–1041. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnum CM. Usability Testing and Research. New York, NY: Longman Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]