Abstract

AMP-activated protein kinase is activated when the catalytic α subunit is phosphorylated on Thr172 and therefore, phosphorylation of the α subunit is used as a measure of activation. However, measurement of α-AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation in vivo can be technically challenging. To determine the most accurate method for measuring α-AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation in the mouse brain, we compared different methods of sacrifice and tissue preparation. We found that freeze/thawing samples after homogenization on ice dramatically increased α-AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation in mice sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Sacrifice of mice by focused microwave irradiation, which rapidly heats the brain and causes enzymatic inactivation, prevented the freeze/thaw-induced increase in α-AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation and similar levels of phosphorylation were observed compared to mice sacrificed with cervical dislocation without freeze/thawing of samples. Sonication of samples in hot 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate blocked the freeze/thaw-induced increase in α-AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation, but phosphorylation was higher in mice sacrificed by cervical dislocation compared to mice sacrificed by focused microwave irradiation. These results demonstrate that α-AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation is dependent on method of sacrifice and tissue preparation and that α-AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation can increase in a manner that does not reflect biological alterations.

Keywords: AMPK, phosphorylation, microwave, brain

Introduction

Recently, there has been increased interest in AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK is implicated as a regulator of energy balance in hypothalamus, liver, muscle, adipose tissue and pancreas (reviewed in Kahn et al. 2005). AMPK also has been implicated in regulation of cell growth and development (Lee et al. 2007) and dysfunction of AMPK and its related pathways can lead to tumors (reviewed in Shaw 2006). AMPK is activated when cellular energy consumed exceeds energy produced and the AMP/ATP ratio increases and, therefore, it functions as a cellular “fuel gauge.” AMPK is a heterotrimer consisting of a catalytic α subunit, of which 2 isoforms have been identified and regulatory β and γ subunits, of which 2 and 3 isoforms have been identified, respectively. During periods of decreased energy availability, AMP increases AMPK activity by binding to the γ subunit which makes α-AMPK a better target for its upstream kinase LKB1 (reviewed in Hardie et al. 2006). LKB1 phosphorylates α-AMPK at the Thr172 amino acid residue leading to AMPK activation (Hawley et al. 2003; Woods et al. 2003; Shaw et al. 2004). AMPK can also be activated in a calcium-dependent manner. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase β can phosphorylate Thr172 on α-AMPK and activate it in a manner independent of the AMP/ATP ratio (Hawley et al. 2005; Hurley et al. 2005; Woods et al. 2005). Therefore, two separate pathways can activate AMPK by phosphorylating the same amino acid residue on α-AMPK.

Once activated, AMPK decreases the energetically costly processes of cholesterol (Carling et al. 1987; Clarke and Hardie 1990), fatty acid (Carling et al. 1987; Browne et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2006) and protein synthesis (Horman et al. 2002; Inoki et al. 2003; Browne et al. 2004; Liu and Gao 2006) by phosphorylating key regulatory proteins. For example, acetyl CoA carboxylase is an important enzyme in switching cellular metabolism from fatty acid oxidation to fatty acid synthesis. AMPK phosphorylates acetyl CoA carboxylase which attenuates fatty acid synthesis and facilitates fatty acid oxidation (Carling et al. 1987; Browne et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2006). AMPK can also alter the transcription of certain target genes by phosphorylating transcription regulating proteins. AMPK phosphorylates transducer of regulated cAMP response element binding protein 2 which prevents its translocation to the nucleus and decreases transcription of gluconeogenic genes (Koo et al. 2005). Therefore, AMPK activation attenuates energy consuming processes which preserves cellular energy.

Given the important role for activation of AMPK via phosphorylation, measuring the degree of phosphorylation provides a method to assess the energy state of the tissue in which this is evaluated. However, one of the challenges in measuring energy-dependent substrates is that rapid changes in metabolites occur at sacrifice. In rats sacrificed by decapitation, there is a large increase in AMP and a concomitant decrease in ATP in the brain compared to rats sacrificed by focused microwave irradiation which rapidly heats the brain rendering enzymes inactive (Delaney and Geiger 1996). Similarly, there is a rapid depletion of glycogen in the astrocytes of the brain from rats that is evident when sacrificed by decapitation since rats sacrificed by focused microwave irradiation display higher brain glycogen levels (Kong et al. 2002). Measurement of phosphorylation also can be challenging for other reasons. It has been demonstrated that glycogen synthase kinase-3 is rapidly dephosphorylated by phosphatases after decapitation with 90% of the dephosphorylation occurring within the first 2 minutes after sacrifice (Li et al. 2005). Likewise, the cyclic AMP response element binding protein and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 are dephosphorylated when mice are sacrificed by decapitation since focused microwave irradiation preserves much higher phosphorylation (O'Callaghan and Sriram 2004). Therefore, given how sensitive AMPK is to the AMP/ATP ratio and the difficulty in general about maintaining in vivo phosphorylation state post-sacrifice, we assessed whether α-AMPK phosphorylation is altered in a manner dependent on method of sacrifice and tissue preparation. We compared two different methods of sacrifice: focused microwave irradiation and cervical dislocation, and various dissection and homogenization procedures. We found that α-AMPK phosphorylation does indeed depend on method of sacrifice and tissue preparation and we propose an approach to accurately assess degree of phosphorylation of AMPK in brain in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Mice

8–32 week old C57BL/6 mice obtained from Jackson Laboratory were maintained on a 12 hour lights on 12 hour lights off, temperature controlled environment. Mice were given ad libitum access to food and water. All procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at either the University of Pennsylvania or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-NIOSH.

Method of sacrifice

Mice were sacrificed by either cervical dislocation or focused microwave irradiation. A Muromachi Microwave Applicator, Model TMW-4012C (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL) was used with a power setting of 3.5 kW applied powerfor 0.9 seconds. A detailed description of the procedure is given elsewhere (O'Callaghan and Sriram 2004).

Brain dissection

After cervical dislocation, all heads were frozen in liquid nitrogen. For the first set of experiments, brains were dissected while frozen. This procedure ensures that the brain temperature does not increase but it is technically challenging and only allows for removal of large segments of the brain. In subsequent experiments, following freezing, heads were thawed on ice until the brains could be easily removed; this brain extraction procedure was similar to the extraction procedure from the mice that were killed with focused microwave irradiation. For these animals sacrificed by cervical dislocation or focused microwave irradiation, the skull was removed and whole brains were extracted including the cerebellum, but not the olfactory bulbs. Samples were kept frozen until tissue preparation.

Tissue preparation

For homogenization on ice, homogenization buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaF, 1% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100 and a protease inhibitor cocktail with broad specificity for the inhibition of serine, cysteine, aspartic proteases and aminopeptidases (Sigma cat# P8340, St. Louis, MO) was used. All chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) unless otherwise noted. In addition, 0.1 μM of the Ser/Thr kinase inhibitor staurosporine (Biomol cat# EI-181, Plymouth Meeting, PA) and 0.1 μM of the Ser/Thr phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid, (Biomol cat# EI-156, Plymouth Meeting, PA) were added to the homogenization buffer. Frozen brain samples were added to the homogenization buffer with the ratio of 7.5 μL of homogenization buffer/mg tissue and homogenized with a Glas-Col homogenizer (cat# 099C K44, Terre Haute, IN) for approximately one minute. For hot sonication, homogenization buffer consisted solely of 1% SDS which was heated to 90°C as described (O'Callaghan and Sriram 2004). Frozen samples were added to the hot homogenization buffer with the ratio of 10 μL of 1% SDS/mg tissue and then immediately sonicated with a model F60 sonic dismembrator (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) for 2 minutes.

Westerns

A protein assay was run on an aliquot of each of the samples to determine total protein concentration using the BCA kit (Pierce, cat# 23235, Rockford, IL). Samples were mixed with a 1:1 volume of Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad, cat# 161-0737, Hercules, CA) with 5% β-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad cat# 161-0710, Hercules, CA) and boiled for 5 minutes. 10 μg of total protein was loaded into a 26 well precast 10% polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad cat# 345-011, Hercules, CA) and run for 110 minutes at 120V. Gels were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore cat# IPFL00010, Billerica, MA) in a wet transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad cat # 170-3946, Hercules, CA) at 55V for 3 hours in tris-glycine buffer with 20% methanol and 0.01% SDS. The apparatus was continuously cooled with a chiller (VWR Scientific, West Chester, PA) to keep the temperature at 4°C and stirred with a magnetic stirrer. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour in blocking buffer (Li-Cor cat #927-40000, Lincoln, NE), and then incubated in primary antibody diluted in 5% bovine serum albumin (VWR, cat# RLBSA-50, West Chester, PA) overnight at 4°C. The antibody for the phosphorylated form of α-AMPK (Cell Signaling, cat #2535, Danvers, MA) was diluted 1:1000 and the antibody for total α-AMPK (Cell Signaling, cat #2532, Danvers, MA) was diluted 1:2000. Four 10 minute washes with phosphate buffered saline with 0.1% tween were done. Membranes were incubated in an infrared-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Li-Cor cat# 926-32221, Lincoln, NE) diluted in blocking buffer with 0.1% tween and 0.01% SDS at room temperature for 1 hour in the dark. Three 10 minute washes with phosphate buffered saline with 0.1% tween were done followed by one 10 minute wash in phosphate buffered saline in the dark. Membranes were dried and then read on an Odyssey Infrared Scanner (Li-cor, cat # 9201-01, Lincoln, NE). Quantification was conducted using the Odyssey software. Data are presented in the units of Odyssey Integrated Intensity which corresponds to amount of infrared light emitted. Since the amount of infrared signal is detected and there is no enzymatic reaction as there is in chemiluminescence, samples can be compared between membranes. However, in this study, all direct comparisons were only done on samples run in one gel and the use of the Odyssey Integrated Intensity is to estimate the relative strength of signals in different blots. n=3 mice per group with each sample run once on a gel and all samples from a given experiment run on a single gel.

Immunoprecipitation

Protein with antibody was incubated overnight at 4°C with continuous mixing on a rotisserie shaker (Barnstead/Thermolyne, model# 415110, Dubuque, IA). 2 μg of antibody for α-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, cat# sc-19128, Santa Cruz, CA) and α-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, cat# sc-19131, Santa Cruz, CA) was added per reaction in a final volume of 80 μL. 50 μL of rProtein G agarose beads (Invitrogen, cat# 15920-010, Carlsbad, CA) was washed with 200 μL of homogenization buffer three times. The protein and antibody mixture was added to the beads and incubated for 1.5 hours at 4°C with mixing. The supernatant was discarded and beads were washed with 200 μL of homogenization buffer two times. 50 μL of Laemmli buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol was added to the beads and boiled immediately for 5 minutes. The supernatant containing the protein was then run on a western blot. n=3 per group with the exception of the 600 μg α-1 AMPK group for which there was n=2.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Seattle, WA) and statistics were run using GB-Stat (version 6.5, Dynamic Microsystems, Silver Spring, MD). When only one comparison was required, Student's t-test was used. For all other data, two way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used with main effects of method of sacrifice and freeze/thaw. When a significant interaction between main factors was present and, therefore, post-hoc comparisons were justified, a Newman-Keuls test for comparisons of the primary analysis was used. All data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

Results

We began our examination by experimenting with different points of boiling during the homogenization procedure to determine if any steps in this procedure alter α-AMPK phosphorylation. Boiling samples denatures the proteins rendering enzymes, including the kinases and phosphatases that alter α-AMPK phosphorylation, inactive. Therefore, if changes in α-AMPK phosphorylation occur during the homogenization procedure, varying the point during the procedure when the samples are boiled could identify a step that alters α-AMPK phosphorylation. Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and the heads were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Brains were dissected while still frozen in order to minimize any changes in phosphorylation that may result from elevations in temperature occurring during the dissection. Brains were homogenized on ice in homogenization buffer containing phosphatase and kinase inhibitors and immediately centrifuged and aliquoted. One set of samples was boiled immediately, another set of samples was mixed with Laemmli buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and boiled, and the final set was frozen at −80°C overnight and then thawed on ice and subsequently mixed with Laemmli buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and boiled. The results of these studies are presented in Figure 1.

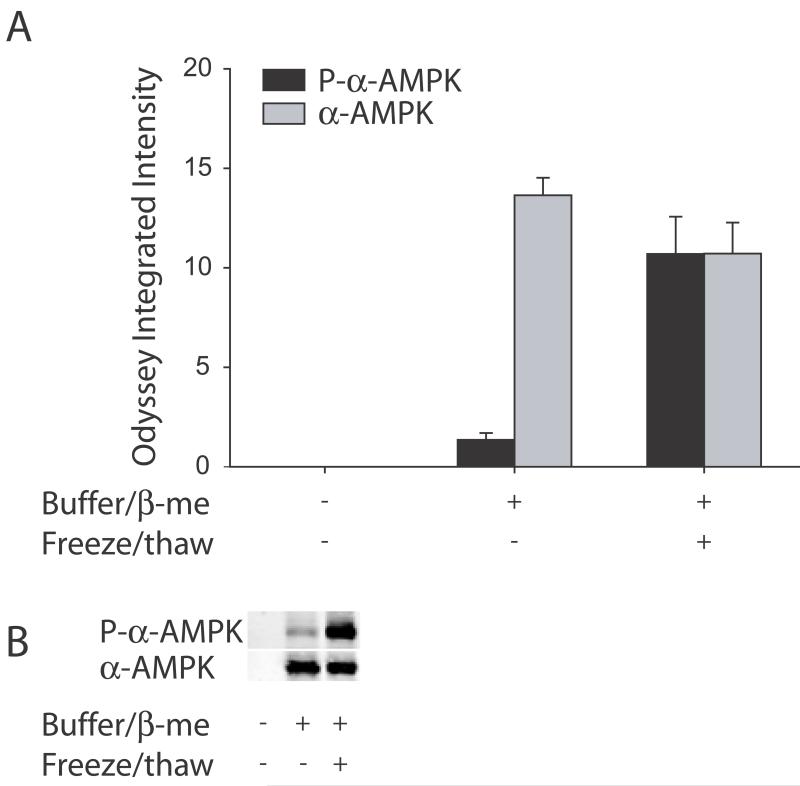

Figure 1.

Freeze/thawing increased α-AMPK phosphorylation. Western blots were run for the phosphorylated form of α-AMPK (black bars) or total α-AMPK (gray bars) including both the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms. The quantified data of all the samples is shown in A. Immediate boiling of samples precipitated out both the phosphorylated α-AMPK and total α-AMPK (first column). Freeze/thawing of samples between the homogenization step and the step where Laemmli buffer with β-mercaptoethanol is added and the samples are subsequently boiled increased phosphorylated α-AMPK but did not alter total α-AMPK (compare middle column to last column). A representative blot is shown in B with a sample that was immediately boiled shown on the first lane, and a sample with Laemmli and β-mercaptoethanol without (middle lane) and with (last lane) freeze/thawing.

Immediate boiling without addition of Laemmli buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol precipitated out all of the protein and there was no detectable phosphorylated α-AMPK or total α-AMPK. Freezing the homogenized samples overnight with a subsequent thawing on ice prior to adding Laemmli buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and boiling increased phosphorylation of α-AMPK approximately 8-fold (P<0.01, Student's t-test) but did not significantly alter total α-AMPK (P>0.05, Student's t-test). Therefore, freeze/thawing samples prior to denaturation led to a large increase in the phosphorylation of α-AMPK that reflects how the samples were handled and not a biological change. That total α-AMPK stays the same indicates that freeze/thawing specifically increases the phosphorylation state of α-AMPK.

Having demonstrated that tissue preparation can alter α-AMPK phosphorylation, we next assessed if method of sacrifice can also affect α-AMPK phosphorylation. We compared mice sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation versus mice that were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The focused microwave irradiation protocol we used raises the core brain temperature to 90°C in less than 1 second (O'Callaghan and Sriram 2004) and, therefore, rapidly inactivates enzymes in the brain and effectively denatures proteins in vivo. For the cervical dislocation group, heads were dropped into liquid nitrogen and then kept on ice until the brains were easily removable so the brain dissection would be similar to that of the mice sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation. We also assessed if α-AMPK phosphorylation in samples taken from mice sacrificed with these two methods was altered by freeze/thawing. All samples were homogenized on ice with homogenization buffer containing kinase and phosphatase inhibitors (as done in the experiments shown in Figure 1). Similar to the previous experiments, after homogenization and aliquoting, Laemmli buffer with β-mercaptoethanol was added to one set of samples which were then boiled immediately and one set was frozen at −80°C overnight and then thawed on ice and mixed with Laemmli buffer with β-mercaptoethanol and boiled. This was done both for brains prepared from mice that were sacrificed by focused microwave irradiation and from mice that were sacrificed with cervical dislocation. The results are presented in Figure 2.

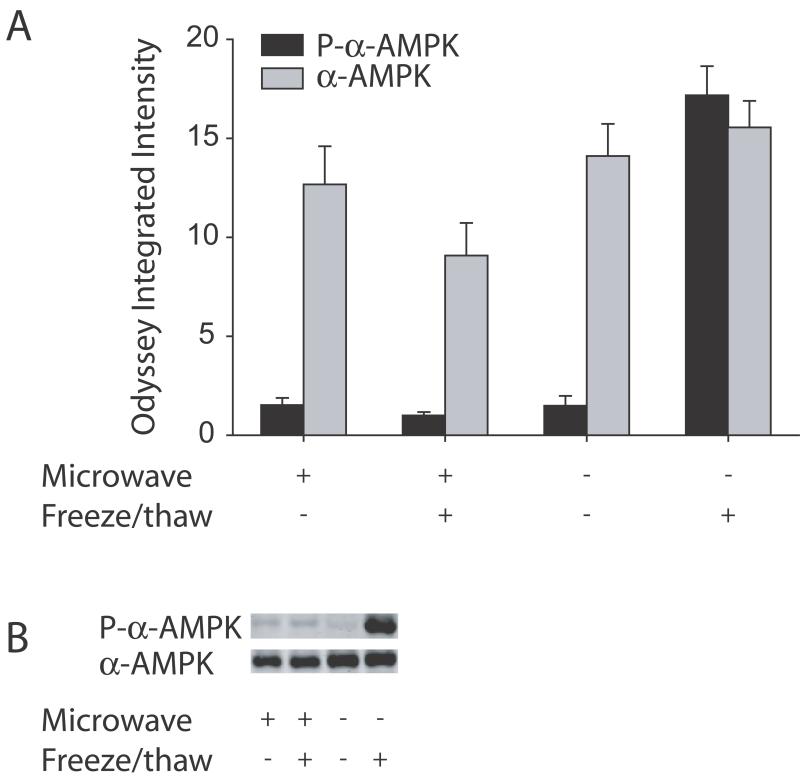

Figure 2.

Focused microwave irradiation sacrifice prevented the freeze/thaw-induced increase in phosphorylation of α-AMPK. Western blots were run for the phosphorylated form of α-AMPK (black bars) or total α-AMPK (gray bars) including both the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms. The quantified data of all the samples is shown in A. In mice sacrificed by cervical dislocation, there was an increase in phosphorylated α-AMPK but no change in total α-AMPK following freeze/thawing (compare the last two columns). In contrast, there was no change in phosphorylated α-AMPK or total α-AMPK in mice sacrificed by focused microwave irradiation following freeze/thawing (compare the first two columns). Furthermore, levels of phosphorylated α-AMPK were similar between mice sacrificed with either cervical dislocation or focused microwave irradiation in the absence of freeze/thawing (compare the first and third columns). A representative blot is shown in B with a sample from a mouse sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation in the absence and presence of freeze/thawing (first two lanes) and a sample from a mouse sacrificed by cervical dislocation in the absence and presence of freeze/thawing (last two lanes).

For phosphorylated α-AMPK, a two-way ANOVA revealed an interaction between method of sacrifice and freeze/thawing (F(1,11)=101.5, P<0.0001). In mice that were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, phosphorylation of α-AMPK increased approximately 12-fold (p<0.01, Newman-Keuls test), similar to what was observed in the previous experiment. However, there was no significant difference in phosphorylation of α-AMPK following freeze/thawing in mice sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation. There was also no significant difference in phosphorylation of α-AMPK between mice sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation or cervical dislocation in the absence of freeze/thawing.

A two-way ANOVA for α-AMPK revealed only a main effect of method of sacrifice (F(1,11)=5.8, P=0.043), but no significant interaction between method of sacrifice and freeze/thawing (F(1,11)=2.3, P=0.165), and no main effect of freeze/thawing (F(1,11)=0.42, P=0.533). This indicated that, averaging over freeze/thaw conditions, total α-AMPK in samples from mice sacrificed by cervical dislocation was higher compared to samples from mice sacrificed by focused microwave irradiation (14.8 for cervical dislocation versus 10.9 for microwave, mean difference of +4.0, 95% CI of +0.2 to +7.8, a 36% increase). However, compared to the 12-fold increase in phosphorylated α-AMPK found in the freeze/thaw condition in mice sacrificed by cervical dislocation, no analogous difference in total α-AMPK was found for freeze/thaw in the cervical dislocation condition (mean difference of −1.1, 95% CI of −4.8 to +2.7) In sum, increased α-AMPK phosphorylation was found following freeze/thawing in samples from mice homogenized on ice and sacrificed by cervical dislocation, but sacrificing the mice with focused microwave irradiation prevented the freeze/thaw-induced increase in α-AMPK phosphorylation.

We also tested another homogenization procedure that instead of using cold in an attempt to preserve phosphorylation, used heat and sonication to try to prevent enzymatic activity and rigorously homogenize the tissue. In this procedure, tissue was sonicated in 1% SDS at 90°C as described (O'Callaghan and Sriram 2004). The design of this experiment was identical to the previous experiment (as shown in Figure 2) with the exception of the tissue homogenization procedure. The results are presented in Figure 3.

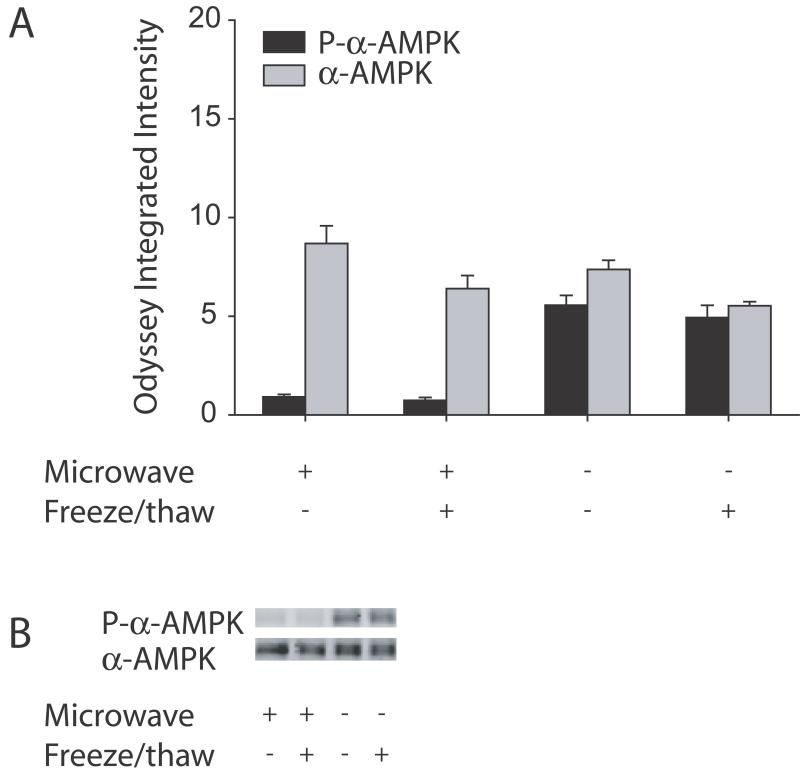

Figure 3.

Hot sonication prevented the freeze/thaw induced increase in phosphorylation of α-AMPK in all groups but increased phosphorylation of α-AMPK in mice sacrificed with cervical dislocation compared to focused microwave irradiation. Western blots were run for the phosphorylated form of α-AMPK (black bars) or total α-AMPK (gray bars) including both the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms. The quantified data of all the samples is shown in A. Levels of phosphorylated α-AMPK were similar following freeze/thawing in mice sacrificed either by focused microwave irradiation (first two columns) or cervical dislocation (last two columns). However, levels of phosphorylated α-AMPK were higher in mice sacrificed by cervical dislocation compared to focused microwave irradiation in the absence (first and third columns) and presence (second and last columns) of freeze/thawing. A representative blot is shown in B with a sample from a mouse sacrificed by focused microwave irradiation in the absence (first lane) and presence (second lane) of freeze/thawing and a sample from a mouse sacrificed by cervical dislocation in the absence (third lane) and presence (last lane) of freeze/thawing.

For phosphorylated α-AMPK, a two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of method of sacrifice (F(1,11)=116.0, P<0.0001), but no significant interaction between method of sacrifice and freeze/thawing (F(1,11)=0.31, P=0.60) and no main effect of freeze/thawing (F(1,11)=0.97, P=0.35). Freeze/thawing did not increase phosphorylation of α-AMPK in brains from mice sacrificed with either cervical dislocation or focused microwave irradiation when the tissue is sonicated in hot 1% SDS. However, cervical dislocation increased phosphorylation of α-AMPK approximately 6-fold compared to focused microwave irradiation in either the presence or absence of freeze/thawing. A similar two-way ANOVA for α-AMPK revealed a main effect of freeze/thawing (F(1,11)=11.4, P<0.01), but no significant interaction between method of sacrifice and freeze/thawing (F(1,11)=0.13, P=0.73) and no main effect of method of sacrifice (F(1,11)=3.2, P=0.11). This indicated that freeze/thawing samples sonicated in hot 1% SDS decreased total α-AMPK. However, there were no differences in total α-AMPK between samples from mice sacrificed with cervical dislocation compared to focused microwave irradiation where there was a 6-fold change in phosphorylated α-AMPK. Furthermore, the decreases in total α-AMPK with freeze/thawing were small (25% and 26%, for samples from mice sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation or cervical dislocation, respectively) and were similar to the non-significant decreases in phosphorylated α-AMPK (19% and 11%, for samples from mice sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation or cervical dislocation, respectively). Therefore, freeze/thawing samples sonicated in hot 1% SDS did not alter phosphorylation of α-AMPK in mice sacrificed with cervical dislocation or focused microwave irradiation but levels of α-AMPK phosphorylation were higher in mice sacrificed by cervical dislocation compared to mice sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation.

We have shown that sacrifice of mice with focused microwave irradiation prevents increases in phosphorylation of α-AMPK that can occur during homogenization. One of the difficulties, however, of sacrifice by focused microwave irradiation is that it “cooks” the brain and makes homogenization on ice in a conventional protein extraction buffer difficult, providing a low total protein yield (3.4 μg/μL ± 0.31 vs. 17.8 μg/μL ± 0.49, for focused microwave irradiation vs. cervical dislocation, respectively, P<0.01). Furthermore, although addition of Laemmli and β-mercaptoethanol and boiling of samples prior to freezing prevents the artificial increase in α-AMPK phosphorylation, these samples may be difficult to use for other applications such as immunoprecipitation since β-mercaptoethanol can interfere with protein binding. These problems are prevented by sonication in hot 1% SDS since there are comparable protein yields between brains from mice sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation or cervical dislocation (10.7 μg/μL ± 0.11 vs. 10.5 μg/μL ± 0.27, for focused microwave irradiation vs. cervical dislocation, respectively, P>0.05). Additionally, as we have shown, sacrifice of mice with focused microwave irradiation and sonication in hot 1% SDS preserves α-AMPK phosphorylation. Such samples can also be used for immunoprecipitations.

In the process of preserving phosphorylation status of α-AMPK by preventing artifactual increases due to methodology, the preserved but lower signal is more difficult to detect and could make identifying small differences between groups very challenging. We addressed the issue of signal magnitude by immunoprecipitating the α-1 and α-2 isoforms of AMPK. Immunoprecipitation offers two advantages. First, increased amounts of total protein loaded on a conventional western blot increase signal strength only to a point after which signal can deteriorate. In our laboratory, we have found the strongest α-AMPK signal when 10 μg of protein is loaded per well beyond which the signal is attenuated (M. Scharf and A.I. Pack, unpublished observations). Immunoprecipitation offers an advantage since much higher amounts of total protein can be added to the reaction. By running immunoprecipitated samples on a western blot where there is only the immunoprecipitated products without all of the excess protein that is loaded on a conventional western blot, larger amounts of the protein of interest can be used and therefore, immunoprecipitation can increase signal strength. Second, selective activation of the different isoforms of α-AMPK occurs (for examples see Jensen et al. 2007; Suzuki et al. 2007) and immunoprecipitation with α-1 or α-2 antibodies allows for elucidation of which isoform is activated by phosphorylation. This is particularly important because it has been suggested that measuring total α-AMPK phosphorylation without isolating the α-1 or α-2 activities may be too crude a measure and may not be sensitive enough to identify true differences in AMPK activation (Jensen et al. 2007).

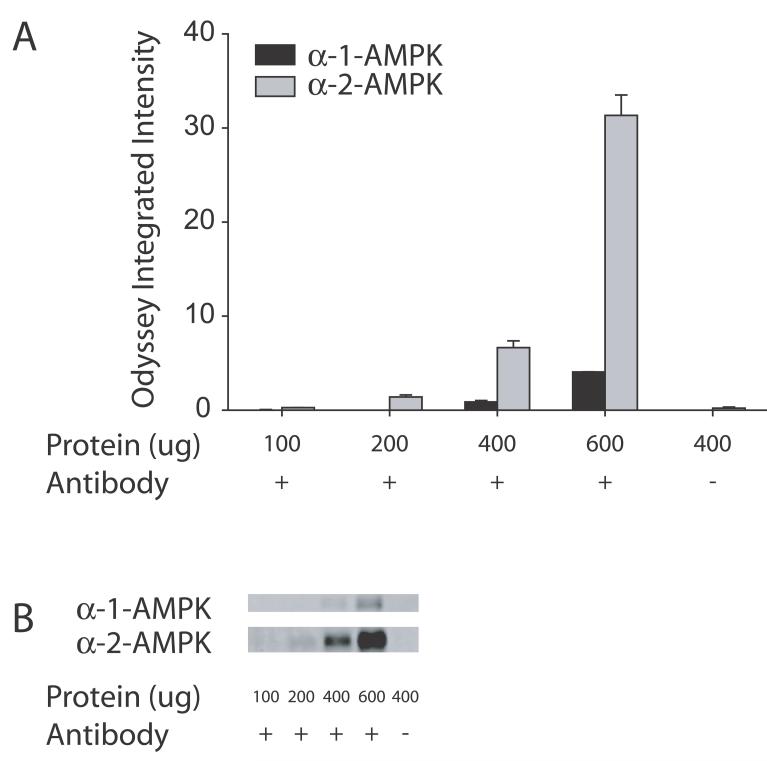

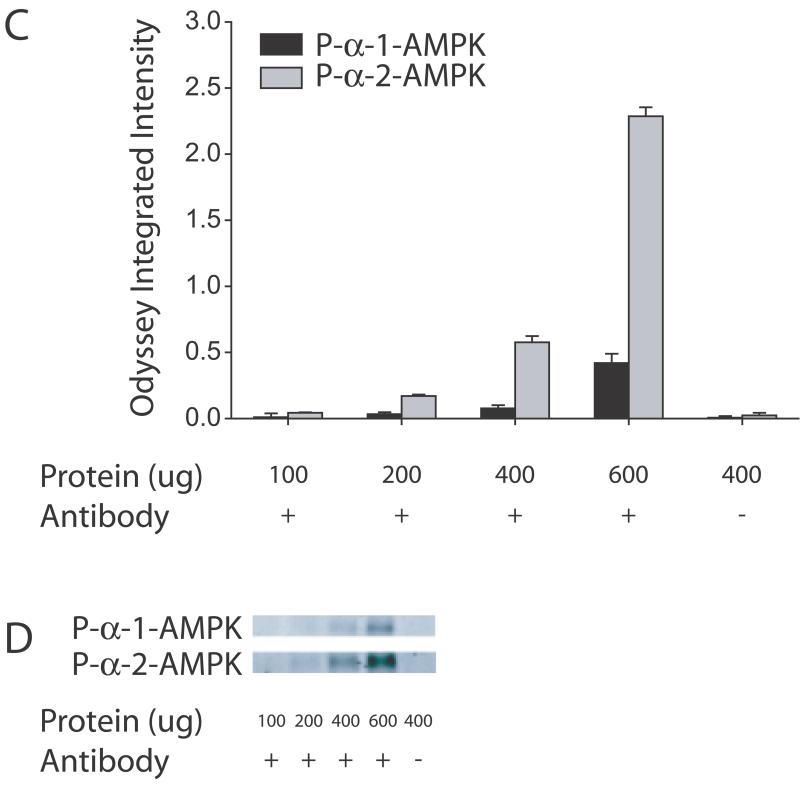

We, therefore, carried out immunoprecipitations for the α-1 and α-2 isoforms of AMPK in brains from mice sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation and sonicated in hot 1% SDS. The data are presented in Figure 4 with different values of Odyssey Integrated Intensity on the y-axis compared to the earlier figures reflecting the range of values observed for the different immunoprecipitations. Thus, the y-axis on this and other figures cannot be directly compared. Progressive increases in total α-AMPK as well as phosphorylated α-AMPK are observed with increasing amounts of total protein. Stronger signals are observed for the α-2 isoform of AMPK which likely reflect that α-2 is the predominant isoform expressed in the brain (Turnley et al. 1999). Interestingly, with 600 μg protein, the α-2 signal is appreciably larger than the samples run by a conventional western for both α-AMPK (31.3 vs. 6.4 Odyssey Integrated Intensity) and phosphorylated α-AMPK (2.29 vs. 0.74 Odyssey Integrated Intensity). As a control, samples were run with no antibody and no signal was observed confirming the specificit of the immunoprecipitation.

Figure 4.

Immunoprecipitation of the α-1 and α-2 subunits of AMPK in samples from mice sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation and sonicated in hot 1% SDS. The quantified data of all the samples is shown in A and C. Immunoprecipitations of the α-1 (black bars) or α-2 (gray bars) subunits of AMPK with increasing amounts of protein were carried out and samples were then probed for α-AMPK (including both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms) as shown in A and phosphorylated α-AMPK as shown in C. As a control, a sample was run with no antibody and no signal was observed (last column on A and C) verifying the specificity of the reaction. A representative blot of one set of samples probed with total α-AMPK is shown in B and phosphorylated α-AMPK is shown in D. Note the values on the y-axis. With 600 μg of protein (second to last column on A and C), values are higher compared to regular western (Figure 3A second column). No signal was observed in a control reaction which is run with no antibody demonstrating the specificity of the reaction (last column, A and C).

Discussion

The activity of many enzymes can be altered by phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of an enzyme can be decreased by phosphatases or increased by kinases. In vivo, kinases and phosphatases modulate activity of enzymes by altering phosphorylation state. However, alterations of measured phosphorylation can also result from the way the animals are sacrificed and the tissue dissected, and hence do not necessarily reflect in vivo phosphorylation. As mentioned previously, the cyclic AMP response element binding protein and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 display markedly reduced phosphorylation in mice sacrificed with decapitation compared to focused microwave irradiation (O'Callaghan and Sriram 2004) and glycogen synthase kinase-3 is rapidly dephosphorylated following decapitation (Li et al. 2005). These changes were suggestive of continued post-sacrifice activity of phosphatases. We questioned if phosphorylation of α-AMPK depends on how animals are sacrificed and how the samples are prepared. We argued that assessing the phosphorylation state of this enzyme would be particularly challenging since it will not only be affected by post-sacrifice activity of phosphatases but also by changes after sacrifice in AMP and ATP which have profound effects on phosphorylation of AMPK. In order to assess phosphorylation state of α-AMPK, we ran western blots specific for the phosphorylated form of α-AMPK and also for total α-AMPK including both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms. All samples were denatured by boiling prior to running the western blots. Denaturing renders enzymes catalytically inactive and therefore kinases and phosphatases can no longer alter phosphorylation. We also tested another method of rendering enzymes inactive by heating, focused microwave irradiation. The focused microwave irradiation protocol we used rapidly heats the brain to 90°C in less than 1 second and therefore destroys enzymes rapidly at the moment of sacrifice (O'Callaghan and Sriram 2004).

We found that freeze/thawing samples following homogenization on ice substantially increases phosphorylation of α-AMPK in mice sacrificed by cervical dislocation. This freeze/thaw-induced increase in α-AMPK phosphorylation is blocked by sacrifice of mice by focused microwave irradiation. Sonication of brains in hot 1% SDS prevents the freeze/thaw-induced increase in α-AMPK phosphorylation but leads to increased phosphorylation in samples from mice sacrificed with cervical dislocation compared to focused microwave irradiation. The difference in α-AMPK phosphorylation in samples from mice sonicated in hot 1% SDS and sacrificed with cervical dislocation compared to focused microwave irradiation is most likely because the brains of mice that were sacrificed with cervical dislocation still contain enzymes that have not been denatured and the brain gradually heats up during sonication in hot 1% SDS so that it is briefly exposed to temperatures that are suitable for enzymatic reactions. This seems especially likely given the size of the samples, allowing for the “core” of a given piece to warm slowly before finally being denatured. It is unlikely that sacrifice of mice with focused microwave irradiation alters α-AMPK phosphorylation per se since similar levels of phosphorylated α-AMPK were observed in samples of mice sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation and mice sacrificed with cervical dislocation in the absence of freeze/thawing when samples were homogenized on ice. Immunoprecipitation of samples allows for isolation of the different isoforms of α-AMPK, and by using increased amounts of protein beyond what can be loaded in a conventional western blot, increases signal strength.

If the enzymes that alter α-AMPK phosphorylation are not inactivated and α-AMPK phosphorylation changes in a manner that does not reflect the biological condition of the animal at the time of sacrifice, variability is introduced that will mask true differences that are occurring. This is poignant since the freeze/thaw-induced increases in α-AMPK phosphorylation observed in our study were between 8 to 12-fold. It is easy to see how such a large increase will mask smaller changes that occur between conditions in vivo. Furthermore, although we did not assess which aspect of freeze/thawing increased α-AMPK phosphorylation, i.e. the freeze/thawing itself or the increased time between homogenization and denaturation, we did demonstrate that differences in processing samples can alter α-AMPK phosphorylation. Thus, slight differences in handling between control and experimental groups may lead to artifactual changes in observed α-AMPK phosphorylation. Therefore, the potential exists for both type 1 errors, concluding that there is an effect where there truly is not, and type 2 errors, concluding an absence of an effect where there really is one.

A similar finding to ours is that assessement of phosphorylation of HMGCoA reductase, one of the downstream targets of AMPK, is sensitive to the method of dissection. When liver is extracted from live, anesthetized mice using a technique known as “cold-clamping” where the tissue is frozen between two metal plates in situ, phosphorylation of HMGCoA reductase is preserved at its lower level, presumed to reflect the in vivo amount (Easom and Zammit 1984a, 1984b). This led to the proposal that it is imperative to use cold-clamping for assessment of phosphorylation of HMGCoA reductase to prevent post-mortem rises in phosphorylation (Hardie et al. 1989). This is consistent with what we observed. Increased phosphorylation of HMGCoA reductase observed without cold-clamping may be due to the increased phosphorylation of α-AMPK that we are reporting.

Changes in both AMPK and HMGCoA reductase with sacrifice are different than that reported for other enzymes, i.e., there is increased phosphorylation, not decreased phosphorylation as produced by the continued action of phosphatases which has been reported for several enzymes and proteins (O'Callaghan and Sriram 2004; Li et al. 2005). We believe the most likely explanation for the methodological-induced increase in α-AMPK phosphorylation is continued activity of upstream kinases that is enhanced by the altered AMP/ATP ratio at sacrifice. We know that the AMP/ATP ratio increases following sacrifice of rats by decapitation compared to focused microwave irradiation (Delaney and Geiger 1996) and that LKB1, one of the upstream kinases of AMPK, increases phosphorylation of α-AMPK in response to an increase in AMP/ATP ratio (Hawley et al. 2003; Woods et al. 2003; Shaw et al. 2004). Enzymatic inactivation either by focused microwave irradiation or immediate denaturation of samples from mice sacrificed with cervical dislocation and homogenized on ice blocks further increases in phosphorylated α-AMPK. These findings support the postulate that the phosphorylation of α-AMPK that is observed in the absence of enzymatic inactivation is due to action of the upstream kinases of AMPK.

ANOVA revealed a small increase in total α-AMPK in samples from mice sacrificed by cervical dislocation and homogenized on ice compared to focused microwave irradiation and a small decrease in total α-AMPK following freeze/thawing in mice sonicated in hot 1% SDS. The changes in phosphorylated α-AMPK cannot be explained as a result of changes in total α-AMPK. First, since there is a clear difference in α-AMPK phosphorylation in mice sacrificed by cervical dislocation following freeze/thawing in samples homogenized on ice where there is no difference in total α-AMPK (Figure 1 and Figure 2, last two columns), it is obvious that these changes in phosphorylated α-AMPK cannot result from changes in total α-AMPK. Second, since the changes we observed in α-AMPK phosphorylation in samples sonicated in hot 1% SDS were only between mice sacrificed with focused microwave irradiation compared to cervical dislocation where no changes in total α-AMPK were observed, the increased phosphorylated α-AMPK also cannot result from increased total α-AMPK. The large-magnitude changes in α-AMPK phosphorylation are not due to changes in total α-AMPK.

The sample sizes used in this study were small (n=3) and therefore geared toward identifying large differences. The reason we opted for small sample sizes was because we were searching for major changes in α-AMPK phosphorylation that could occur with sacrifice and tissue preparation. It is possible that small differences do exist that we did not identify. However, since our purpose was to assess large-scale changes in α-AMPK phosphorylation, we believe the sample size was appropriate.

The addition of kinase and phosphatase inhibitors to the homogenizations done on ice was not sufficient to prevent increases in α-AMPK phosphorylation following freeze/thawing. Perhaps these inhibitors were not at a sufficient concentration to be effective or were simply not suitable for AMPK. It is possible that more selective inhibition of the upstream kinases of AMPK may allow for blocking the freeze/thaw-induced increase in α-AMPK phosphorylation. There are two known upstream kinases of AMPK, LKB1 and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase β. STO-609 inhibits calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase β activity (Tokumitsu et al. 2002) but no known chemicals directly inhibit LKB1 activity. Therefore, at this point there are no appropriate chemicals to stabilize AMPK. Additionally, compounds may not effectively reach the cellular compartments of the cells where AMPK is located in a manner sufficient to block artifactual AMPK phosphorylation.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated how α-AMPK phosphorylation can change dependent on method of sacrifice and tissue preparation. We propose that sacrifice of mice by focused microwave irradiation followed by homogenization in hot 1% SDS is the optimal strategy for measurement of α-AMPK phosphorylation. First, the rapid heating of the brain renders enzymes catalytically inactive and blocks the artifactual increase in AMPK phosphorylation. Second, samples can then be used for applications such as immunoprecipitation, which allows for identification not only of α-AMPK activation, but also which isoform of α-AMPK is activated by phosphorylation and provides a stronger signal.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grants from the NIH (HL-07953, AG-17628). The authors thank Christopher Felton for technical assistance and Jacqueline Cater for assistance with statistical analysis.

Abbreviations

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- α-AMPK

α subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

References

- Browne GJ, Finn SG, Proud CG. Stimulation of the AMP-activated protein kinase leads to activation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase and to its phosphorylation at a novel site, serine 398. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12220–12231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carling D, Zammit VA, Hardie DG. A common bicyclic protein kinase cascade inactivates the regulatory enzymes of fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 1987;223:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke PR, Hardie DG. Regulation of HMG-CoA reductase: identification of the site phosphorylated by the AMP-activated protein kinase in vitro and in intact rat liver. Embo J. 1990;9:2439–2446. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney SM, Geiger JD. Brain regional levels of adenosine and adenosine nucleotides in rats killed by high-energy focused microwave irradiation. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;64:151–156. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easom RA, Zammit VA. A cold-clamping technique for the rapid sampling of rat liver for studies on enzymes in separate cell fractions. Suitability for the study of enzymes regulated by reversible phosphorylation-dephosphorylation. Biochem J. 1984a;220:733–738. doi: 10.1042/bj2200733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easom RA, Zammit VA. Diurnal changes in the fraction of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase in the active form in rat liver microsomal fractions. Biochem J. 1984b;220:739–745. doi: 10.1042/bj2200739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG, Carling D, Sim AT. The AMP-activated protein kinase: a multisubstrate regulator of lipid metabolism. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1989;14:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG, Hawley SA, Scott JW. AMP-activated protein kinase--development of the energy sensor concept. J Physiol. 2006;574:7–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley SA, Boudeau J, Reid JL, Mustard KJ, Udd L, Makela TP, Alessi DR, Hardie DG. Complexes between the LKB1 tumor suppressor, STRAD alpha/beta and MO25 alpha/beta are upstream kinases in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. J Biol. 2003;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley SA, Pan DA, Mustard KJ, Ross L, Bain J, Edelman AM, Frenguelli BG, Hardie DG. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta is an alternative upstream kinase for AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Metab. 2005;2:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horman S, Browne G, Krause U, Patel J, Vertommen D, Bertrand L, Lavoinne A, Hue L, Proud C, Rider M. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase leads to the phosphorylation of elongation factor 2 and an inhibition of protein synthesis. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1419–1423. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley RL, Anderson KA, Franzone JM, Kemp BE, Means AR, Witters LA. The Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinases are AMP-activated protein kinase kinases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29060–29066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TE, Rose AJ, Hellsten Y, Wojtaszewski JF, Richter EA. Caffeine-induced Ca2+ release increases AMPK-dependent glucose uptake in rodent soleus muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E286–292. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00693.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2005;1:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Shepel PN, Holden CP, Mackiewicz M, Pack AI, Geiger JD. Brain glycogen decreases with increased periods of wakefulness: implications for homeostatic drive to sleep. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5581–5587. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05581.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo SH, Flechner L, Qi L, Zhang X, Screaton RA, Jeffries S, Hedrick S, Xu W, Boussouar F, Brindle P, Takemori H, Montminy M. The CREB coactivator TORC2 is a key regulator of fasting glucose metabolism. Nature. 2005;437:1109–1111. doi: 10.1038/nature03967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Koh H, Kim M, Kim Y, Lee SY, Karess RE, Lee SH, Shong M, Kim JM, Kim J, Chung J. Energy-dependent regulation of cell structure by AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature. 2007;447:1017–1020. doi: 10.1038/nature05828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Friedman AB, Roh MS, Jope RS. Anesthesia and post-mortem interval profoundly influence the regulatory serine phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in mouse brain. J Neurochem. 2005;92:701–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Cash TP, Jones RG, Keith B, Thompson CB, Simon MC. Hypoxia-induced energy stress regulates mRNA translation and cell growth. Mol Cell. 2006;21:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZW, Gao XB. Adenosine inhibits activity of hypocretin/orexin neurons via A1 receptor in the lateral hypothalamus: a possible sleep-promoting effect. J Neurophysiol. 2006 doi: 10.1152/jn.00873.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan JP, Sriram K. Focused microwave irradiation of the brain preserves in vivo protein phosphorylation: comparison with other methods of sacrifice and analysis of multiple phosphoproteins. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;135:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RJ. Glucose metabolism and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:598–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RJ, Kosmatka M, Bardeesy N, Hurley RL, Witters LA, DePinho RA, Cantley LC. The tumor suppressor LKB1 kinase directly activates AMP-activated kinase and regulates apoptosis in response to energy stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3329–3335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308061100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Okamoto S, Lee S, Saito K, Shiuchi T, Minokoshi Y. Leptin stimulates fatty acid oxidation and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha gene expression in mouse C2C12 myoblasts by changing the subcellular localization of the alpha2 form of AMP-activated protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4317–4327. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02222-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumitsu H, Inuzuka H, Ishikawa Y, Ikeda M, Saji I, Kobayashi R. STO-609, a specific inhibitor of the Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15813–15818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnley AM, Stapleton D, Mann RJ, Witters LA, Kemp BE, Bartlett PF. Cellular distribution and developmental expression of AMP-activated protein kinase isoforms in mouse central nervous system. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1707–1716. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods A, Dickerson K, Heath R, Hong SP, Momcilovic M, Johnstone SR, Carlson M, Carling D. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta acts upstream of AMP-activated protein kinase in mammalian cells. Cell Metab. 2005;2:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods A, Johnstone SR, Dickerson K, Leiper FC, Fryer LG, Neumann D, Schlattner U, Wallimann T, Carlson M, Carling D. LKB1 is the upstream kinase in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Curr Biol. 2003;13:2004–2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]