Abstract

Epidemiologic evidence suggests that a diet rich in fruits and vegetables is associated with a reduced risk of prostate cancer (PCa) development. Although several dietary compounds have been tested in preclinical PCa prevention models, no agents have been identified that either prevent the progression of premalignant lesions or treat advanced disease. Momordica charantia, known as bitter melon in English, is a plant that grows in tropical areas worldwide and is both eaten as a vegetable and used for medicinal purposes. We have isolated a protein, designated as MCP30, from bitter melon seeds. The purified fraction was verified by SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry to contain only 2 highly related single chain Type I ribosome-inactivating proteins (RIPs), α-momorcharin and β-momorcharin. MCP30 induces apoptosis in PIN and PCa cell lines in vitro and suppresses PC-3 growth in vivo with no effect on normal prostate cells. Mechanistically, MCP30 inhibits histone deacetylase-1 (HDAC-1) activity and promotes histone-3 and -4 protein acetylation. Treatment with MCP30 induces PTEN expression in a prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) and PCa cell lines resulting in inhibition of Akt phosphorylation. In addition, MCP30 inhibits Wnt signaling activity through reduction of nuclear accumulation of β-catenin and decreased levels of c-Myc and Cyclin-D1. Our data indicate that MCP30 selectively induces PIN and PCa apoptosis and inhibits HDAC-1 activity. These results suggest that Type I RIPs derived from plants are HDAC inhibitors that can be utilized in the prevention and treatment of prostate cancer.

Keywords: ribosome inactivating protein, HDAC inhibitor, prostate cancer, tumor suppresive gene, dietary factors

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the second leading of cancer deaths in U.S. males.1 High-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) is considered a premalignant lesion and the factors which stimulate or inhibit HGPIN growth have not been fully elucidated.2,3 As this is a highly prevalent disorder with no curative therapies for advanced disease,4,5 there is a need to develop novel dietary preventive and therapeutic strategies.

The tumor suppressor gene phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) is both a lipid phosphatase and protein phosphatase. As a lipid phosphatase, PTEN functions as an inhibitor of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI-3K)/Akt pathway.6 PTEN alteration is strongly implicated in PCa development. Silencing of PTEN is frequently associated with advanced PCa and likely plays a critical role in promoting PI3K/Akt gain-of-function.7 Recent reports demonstrate that PTEN gene expression can be induced at the promoter level by a dietary compound, genestein and an HDAC inhibitor, Trichostatin A.8,9

Recent attention has focused on the role of epigenetic factors in PCa development and progression. Both dietary and environmental factors have been shown to induce epigenetic changes, including methylation, phosphorylation and acetylation of both DNA and proteins. Histone deacetylases (HDACs) catalyze the removal of acetyl groups from histones, leading to chromatin condensation and transcriptional repression. In human cancers, HDACs have been demonstrated to interact with oncogenic fusion proteins in acute leukemia10 and to be overexpressed in several tumor types including prostate,11 gastric,12 colon13 and breast cancer.14 More recently, it has been shown that global hypo-acetylation of Histone-H4 is a common hallmark of human tumors. Changes in H4 acetylation occur early in the tumorigenic process indicating that treatment with HDAC inhibitors may restore a “normal” epigenetic state, or selectively induce tumor-suppressive gene expression and function.15

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is commonly dysregulated in cancers, including PCa.16 Nuclear β-catenin is a critical component of the Wnt signaling pathway that serves as an activator of T-cell factor (Tcf)-dependent transcription, leading to increased expression of several target genes including c-myc and Cyclin D1 that stimulate cellular proliferation.17 The β-catenin transcriptional activator complex continues to be defined, but is known to contain several proteins with chromatin remodeling activity, including histone acetyltransferases.18 Wnt/β-catenin signaling is stimulated by the Akt pathway19,20 via inhibition of GSK3β activity and suppressed by PTEN.21,22 In addition, a recent report demonstrated that Wnt transcriptional activity can be modulated by an HDAC inhibitor in human colorectal carcinoma cells.23

Epidemiologic evidence strongly suggests that diets rich in fruit and vegetables are associated with reduced risks of PCa.24 Recent preclinical studies demonstrate some efficacy of specific dietary compounds in prevention models.25,26 However, none of these compounds have yet been proven to treat primary or metastatic disease. Momordica charantia (MC), known as bitter melon or bitter gourd in English, is a plant that grows in tropical areas of Asia, Amazon, East Africa and the Caribbean. The fruit and seed extracts of MC have been used in China for centuries for anti-viral, anti-tumor and immunopotentiating purposes.27,28 In recent years, several proteins have been isolated from the seed extracts of the plant and used to treat a variety of disorders including diabetes and cancer.27,29-32 These proteins belong to the Type I family of single chain ribosome-inactivating proteins (RIPs) which inhibit in vitro translation of eukaryotic cells by catalytic inactivation of the 60s ribosomal subunit and inhibit the replication of herpes simplex virus- (HSV-1) and of poliovirus I in Hep-2 cells.27 Moreover, these extracts have been demonstrated to have in vivo preventive effects against colon and breast cancer31,32 because of their anti-tumor activity and immunostimulatory ability. However, the precise molecular mechanisms of action whereby bitter melon protein and other plant-derived Type I RIPs inhibit cancer cells have not been fully elucidated.

In our study, we isolated a 30 kDa protein from bitter melon seeds (MCP30) that contains 2 highly related Type I ribosome-inactivating proteins. MCP30 inhibits the growth of human PIN and PCa cell lines in vitro primarily by inducing apoptosis, with no effect on normal human prostate epithelial cells. MCP30 also significantly suppressed the in vivo growth of PC3 human prostate cancer cells. This growth inhibition is accompanied by decreased HDAC-1 levels and activity, induction of PTEN protein, suppression of Wnt signaling activity and decreased levels of c-Myc and Cyclin-D1 in the PIN and PCa cell lines.

Material and methods

Cell culture and reagents

The LNCaP, PC-3 and RWPE-1 cell lines were obtained from the American Type Tissue Collection (ATCC). The human prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) cell line was a generous gift from Dr. M. Stearns (Department of Pathology, MCP-Hahnemann University, Philadelphia, PA). This cell line was established by human papilloma virus-18 immortalization of PIN cells from radical prostatectomy specimens and has been reported to express prostate specific antigen and cytokeratin 34βE12, thereby establishing their PIN cell origin.33 PIN and RWPE-1 cells were cultured in keratinocyte medium; PC-3 cells were cultured in DMEM and LNCaP cells were maintained in RPMI 1640. All culture mediums were supplemented with 10% FBS. The Enhanced Luciferase Assay kit was obtained from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Antibodies against PTEN, c-Myc, Cyclin D1, HDAC-1 and β-actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against active β-catenin and antibodies against total histone 3, 4 and acetyl-histone 3, 4 were purchased from Upstate (Lake Placid, NY). Antibodies against phospho-GSK and endogenous GSK were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA).

Isolation of protein from bitter melon seeds

Bitter melon seeds were purchased from a local market in the suburbs of Shanghai, China. The extraction and purification procedures were performed according to the methods described by Barbieri et al.,34 Lee-Huang et al.,27 and Ye et al.,35 with modification for extraction. Briefly, bitter melon seeds were decorticated, pulverized and homogenized with 10 mM sodium phosphate (SP) buffer (pH 7.0) at a ratio of 6 mL SP solution per gram of seeds. The mixture was then stirred for 48 hr. The debris were removed by filtration with 4 layers cheesecloth and centrifuged at 10,000g for 30 min. Pre-cooled acetone was then added to the supernatant, mixed and kept at 4°C for 30 min. After centrifugation, the precipitates were dissolved in 10 mM SP buffer and dialyzed against the same buffer for 48 hr. The pellets were removed by centrifugation and the supernatant was applied to a SP Sepharose High Performance column (2.2 cm × 40 cm, Pharmacia, Sweden), and eluted with a linear gradient of 0-0.125 M NaCl in SP buffer, which resulted 4 peak-through fractions (CM1, CM2, CM3 and CM4) with molecular weight of 30 kDa assayed by SDS-PAGE (data not shown). The fraction of CM4 was further purified by gel filtration with a Sephdex G-75 column (Pharmacia) and analyzed by iso-electric focusing electrophoresis (data not shown). The protein was designated as MCP30.

Tryptic digestion

Tryptic digestion was performed as previously described.36,37 Briefly, the silver-stained gel bands were excised and destained with a 50 μL 1:1 mixture of 30 mM potassium ferricyanide (Sigma, MO) and 100 mM sodium thiosulfate (Sigma) in a siliconized tube until brownish stain disappeared (~5 min). Reduction of disulfides was then performed with 10 mM dithiothreitol in 100 mM NH4HCO3 for 30 min at 55°C, followed by alkylation with iodoacetamide in 100 mM NH4HCO3 for 45 min in the dark. After washings with 40 mM NH4HCO3, the gel pieces were minced, dehydrated with acetonitrile (ACN), dried in SpeedVac and subjected to trypsin digestion using Trypsin Gold (Promega, WI) for 18 h at 37°C. Peptides were extracted successively with 1% formic acid (FA)/50% ACN, 80% ACN/1% FA and 100% ACN and then purified by Ziptip (Millipore, MA).

Mass spectrometry

The digest was analyzed by capillary LC-MS/MS using a Finnigan LTQ-Orbitrap (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA). Half of the digest was loaded directly onto the 75 μm × 100 mm PicoFrit capillary column (New Objective, MA) packed with MAGIC C18 (100 Å 5 μ, Michrom Bioresources, CA) at a flow rate of ~300 nL/min, and peptides were separated by a gradient comprised of 2–60% ACN/0.1% FA in 30 min, 60–98% ACN/0.1% FA in 4 min and a hold at 98% ACN/0.1%FA for 2 min. The LTQ-Orbitrap was operated in standard data dependent “Top Three” mode with a survey scan from m/z 300–1,600 at 60,000 resolution in the Oribitrap paralleled by 3 MS/MS scans in the LTQ. Exclusion duration was set for 3 min. Minimum signal threshold was 250.

Database searching (SEQUEST)

The product ion spectra were searched against a database, which contained Momordica charantia and bovine entries subtracted from UniProtRef100, using the SEQUEST search engine in Bioworks 3.3. The database were indexed with the followings: fully enzymatic activity and two missed cleavage sites allowed for trypsin; peptides MW of 600-6,000 kDa; SEQUEST search parameters were as follows: mass tolerance of 10 ppm and 1 amu for precursor and fragment ions, respectively; three differential/post-translational modifications allowed per peptide; variable modification on methionine [+15.9949 amu for oxidized methionine and +57.0214 (carboxyamindomethylation) on cysteine]. Analysis was performed in Bioworks 3.3 by applying filters of XCorr [2.0 (2+), 2.5(3+)]; DelCN (=/> 0.1)] and precursor mass accuracy </= 10 ppm, and protein identifications were ranked by protein probability P (pro). The MS/MS spectra of peptides were evaluated by Scaffold (Proteome Software, OR).

Protein isolation and immunoblotting

Cells cultured under the indicated conditions were lysed and total protein was isolated as described previously.38 Proteins from the cytosolic and nuclear fractions were isolated using a commercial kit purchased from PIERCE (Rockford, IL), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein content was assayed using a kit from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Western blotting was performed as previously described.38 β-actin was used as the internal control in Western blot analyses.

HDAC activity assay

HDAC activity was measured using the HDAC Fluorescent Activity assay kit according to the instructions from the manufacturer (Cayman Co., Ann Arbor, MI). Briefly, 15 μL nuclear fraction or 5 μL HDAC1 immunoprecipitate preparation was diluted to 25 μL with the assay buffer. After the addition of fluorogenic HDAC substrate, the reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and stopped by 50 μL “developer” cocktail. The fluorescence of the reaction mixture was monitored at excitation350 nm/emission460 nm using a SPECTRAmax Gemini plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

RNA extraction and quantitative real time reverse PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent® (Sigma, St. Loius, MO). RNA concentration was measured by spectrophotometry. Synthesis of cDNA was performed on 2 μg of total RNA per sample with random primers using reagents contained in the reverse transcription system kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega Co., Madison, WI). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was performed by the Taqman system (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Oligonucleotides were designed by the PrimerExpress software. Fluorescence signals were analyzed during each of 40 cycles (denaturation, 15 sec at 95°C; annealing, 15 sec at 56°C; and extension, 40 sec at 72°C). Relative quantitation was calculated using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method as described in the User Bulletin 2, ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). Mean CT of duplicate measurements was used to calculate ΔCT as the difference in CT for target and reference. β-Actin was used as a housekeeping gene for normalization, and H2O was used as a negative control. Amplifications were performed using oligonucleotide primers for PTEN: forward primer, 5′-GCT-ATG-GGG-TTT-CCT-GCA-G-3, and reverse, 5′-GCT-GTG-GTG-GAT-TAT-GGT-CTT-C-3; for β-actin: forward, 5′-GAT-GAG-ATT-GGC-ATG-GCT-TT-3′, and reverse, 5′-AGA-GGT-GGG-GTG-GCT-T-3′.

Transient transfection and luciferase reporter assay

Transient transfection was performed using LipofectAMI-NE™2000 reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The Tcf luciferase reporter construct pGL3-OT and control vector were generously provided by Dr. B. Vogelstein (John Hopkins Oncology Center, Baltimore, MD). Cells were cultured in 12-well cluster plates and transfected with either 1 μg of the reporter plasmid or empty vector as a mock control. Internal normalization was performed by co-transfection of the β-galactosidase expression vector (BD ClonTech). After 48 hr, the transfected cells were lysed by scraping into reporter buffer (BD ClonTech), total protein concentration was determined, and luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were assayed and quantitated using a TD-20e Luminometer. The resulting activities were normalized to protein concentrations and β-galactosidase activity.

TUNEL assay

Tumor specimens from control vs. MCP30-treated mice were deparaffinized and washed in 2 changes of xylene for 5 min each wash, followed by washing in ethanol and PBS. Tumor specimens were examined for apoptosis using the TUNEL method with the ApopTag in situ apoptotic detection kit (Oncor, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The fixed tissues were examined using a fluorescent microscope.

Flow cytometry

Cells were cultured in their optimal medium, 1 × 106 cells were trypsinized, washed once in ice-cold PBS and resuspended in 0.2 mL PBS. Cells were then fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol for 30 min and incubated with the fluorescent dye propidium iodide (50 μg/mL) and RNase A (0.1 μg/mL) at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. After centrifugation, samples were resuspended in 1 mL PBS and analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). The percentage of apoptotic cells and cells in G0/G1, S and G2/M phases were calculated.

In vivo study

Male mice aged 6–8 weeks were used in the study. For tumor cell inoculation, subconfluent PC-3 cells were harvested with 0.1% trypsin. Ten million cells were suspended in 1 mL of 10% FBS-containing DMEM (GibcoBRL, Gaithersburg, MD) and mixed with 1 volume of ice-cold Matrigel (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA). The cell-matrigel suspension was allowed to warm up at room temperature for 5 min with gentle mixing and then inoculated subcutaneously into the inguinal region of each mouse. From the second week of tumor cell inoculation, tumor bearing mice were randomly divided into 2 groups with 10 mice each and received intraperitoneal injections of either vehicle as control or MCP30 at the dose of 0.5 mg/kg body weight twice a week. Animals were weighed and the tumor surface areas were measured with a vernier caliper at weekly intervals. The formula (L/2) × (W/2) × π (where L is maximum diameter of each tumor, and W is the length at right angles to L) was used to calculate the tumor surface areas.39,40

Statistical analysis

All results are given as mean ± SE. The effects induced by the various treatments were compared to untreated control cells utilizing paired Student’s t test with the Bonferroni adjustment for the comparison of multiple groups. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

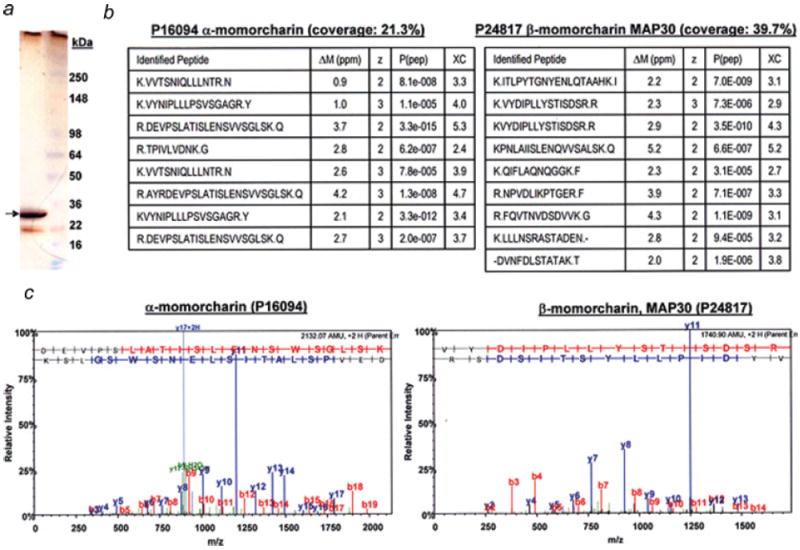

Mass spectrometry of MCP30

Gel electrophoresis of the purified fraction (MCP30) revealed a strong silver-stained band at around 30 kDa and a very faint band at around 22 kDa (Fig. 1a). After mass spectrometric analysis and subsequent interrogating the mass spectrometry data with a database searching algorithm (SEQUEST), the only proteins, in the major band (30 kDa), that could be confidently identified (with 2 or more unique peptides), were α-momorcharin (6 unique peptides; sequence coverage: 21.3%) and β-momorcharin (MAP30) (8 unique peptides; sequence coverage: 39.7%) (Fig. 1b). All MS/MS spectra of the identified peptides of α and β momorcharin showed a continuous b- or y-ion series and have the top intense peaks in the spectra assigned to a, b, y-ion (or such ions minus a neutral loss of water/ ammonia) or multiply charged fragment ions. A representative MS/MS spectrum of the peptide with the highest score identified from α- and β-momorcharin is shown in Figure 1c. Mass spectrometry was also performed on the lower faint silver stained band (22 kDa), the only protein identified with 2 peptides was α-momorcharin (with a sequence coverage of 16.4%), whereas β-momorcharin was only identified with one peptide. This faint gel band may suggest that partial degradation of these 2 proteins occurred during the purification steps. Identified α- and β-momorcharin share 53% amino acid identity.

Figure 1.

Protein identification of the purified fraction (MCP30). (a) Gel electrophoresis of MCP30. The purified fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (4–12%) and the gel stained with silver staining. (b) Mass spectrometry analysis. The major band (indicated by an arrow) was excised, subjected to tryptic digestion and the digest was analyzed by mass spectrometry. After database searching of the mass spectrometric data using SEQUEST, the only proteins confidently identified (with 2 or more peptides) in the major band were alpha-momorcharin (sequence coverage: 21.3%) and beta-momorcharin (MAP30) (sequence coverage: 39.7%). ΔM (mass difference between measured and theoretical tryptic fragments); z, charge state; P(pep), peptide probability; XC, cross correlation. (c) MS/MS spectrum. The MS/MS spectrum of the peptide with the highest score (peptide probability) of α- and β-momorcharin is shown. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

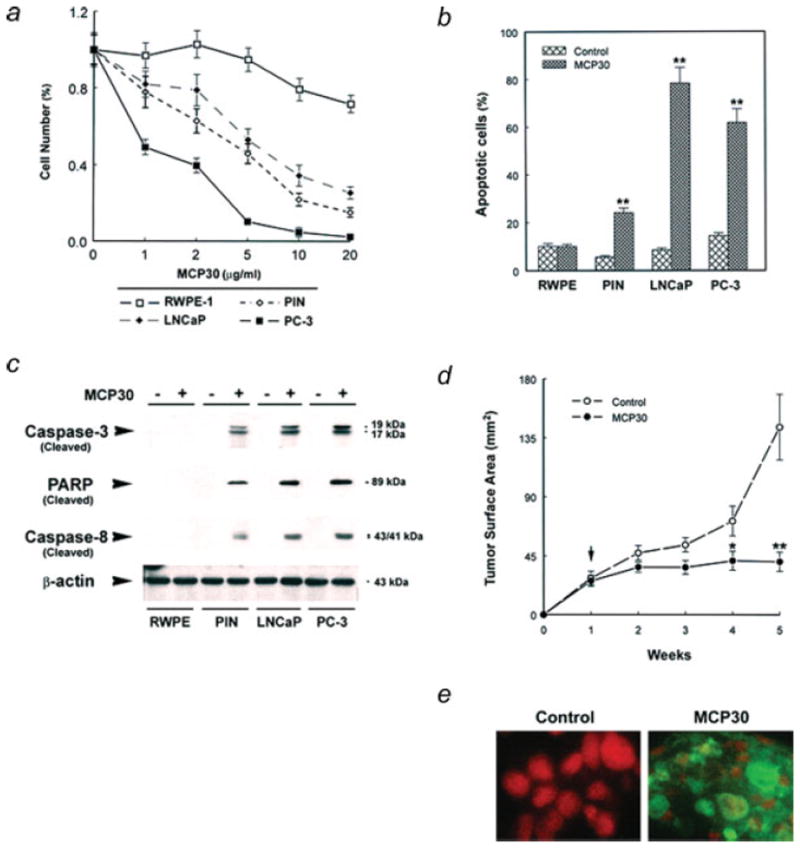

MCP30 induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in PIN and PCa cell lines

We tested the effects of MCP30 on the growth of 4 prostate-derived cell lines, i.e., PC-3, LNCaP, PIN and RWPE-1 (a normal human prostate epithelial cell line). Figure 2a demonstrates that MCP30 selectively inhibited the growth of the PC-3, LNCaP and PIN cell lines with no demonstrable effect on RWPE-1 cells. To ascertain whether these differences in cell growth were due to the induction of apoptosis or cell cycle arrest we performed FACS analysis. As shown in Figure 2b, MCP30 induced a significant increase in apoptosis in PIN and both PCa cell lines (LNCaP and PC-3) with no effect on RWPE-1 cells. The flow cytometry data also demonstrated significant accumulation of PIN, LNCaP and PC-3 cells (PIN > PC-3 > LNCaP) in the G0 phase of the cell cycle (data not shown) after MCP30 treatment, indicating that, in addition to the pro-apoptotic effects, the compound induced cell cycle arrest. To confirm activation of the apoptotic cascade we performed western blot analysis for general markers of apoptosis. All markers analyzed, including cleaved caspases-3 and -8 and cleaved PARP revealed increased expression (Fig. 2c), confirming that MCP30 induces apoptosis specifically in PIN and PCa cell lines.

Figure 2.

MCP30 induces apoptosis in PIN and PCa cell lines and suppresses PC-3 cell tumor growth in nude mice. Prostate-derived cell lines were plated and maintained in their optimal medium overnight. (a) The medium was changed to serum-free medium and treated with various doses of MCP30 for 7d. The number of living cells was counted using a hemacytometer. Data are expressed as means ± SE of 3 wells from 3 separate experiments. (b) Apoptotic cells were determined using flow cytometric analysis. Data are expressed as means ± SE of 3 wells from three separate experiments. **p < 0.01 as compared to control for each cell line. (c) Cells were treated with or without MCP30 (10 μg/mL) for 7d. Total protein was isolated and subjected to Western blot analysis using antibody against caspase-3. The same blot was stripped and sequentially reprobed with antibodies against PARP, caspase-8 and β-actin. Data shown are representative of 3 separate experiments. (d) From second week of PC-3 cell inoculation, tumor bearing mice were randomized to receive i.p. injections of either vehicle as control or MCP30, 0.5 mg/kg body weight, twice a week. Tumor surface areas were examined weekly. Vertical arrow indicates the time for initiation of MCP30 treatment. (e) TUNEL of histological sections of tumors derived from control vs. MCP30-treated mice. Tumors were removed and processed to TUNEL assay for identification of apoptotic cells.

MCP30 suppresses PC-3 cell tumor growth in nude mice

We next examined the in vivo efficacy of MCP30 on PCa tumor growth in nude mice. As shown in Figure 2d, over a 5-week experimental period, MCP30, at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg body weight given intraperitoneally (i.p.) twice a week, produced a sustained inhibition of PC-3 cell tumor growth beginning at the second week after treatment. Average tumor surface area for the MCP30 treated-mice at 5 weeks was 40.6 mm2 vs. 143.8 mm2 from control mice (p < 0.001). At the time of sacrifice, tumors from control mice were larger and grossly appeared to be more highly vascularized than those derived from MCP30-treated mice. However, immunohistochemical analysis of treated vs. control tumors did not reveal any differences in microvessel density (MVD), as assessed by staining for Factor-VIII-related antigen, or proliferation, as assessed by PCNA staining (data not shown). There were significant differences, however, in TUNEL staining with this marker of apoptosis noted only in the treated tumors (Fig. 2e).

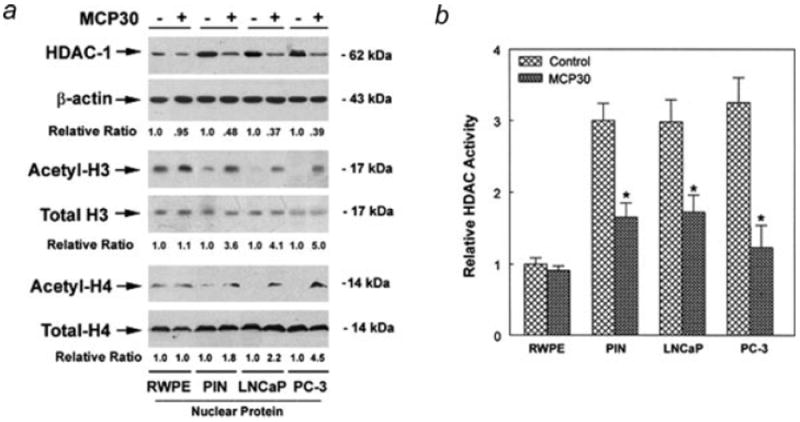

Bitter melon protein (MCP30) inhibits HDAC-1 activity

To explore the possible mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effect of MCP30 on PCa and PIN cell viability, we compared HDAC1 expression and activity after MCP30 treatment in the prostate-derived cell lines. Figure 4 demonstrates that treatment of prostate-derived cell lines with MCP30 decreased HDAC-1 expression (Fig. 3a) and HDAC activity (Fig. 3b) in PC-3, LNCaP and PIN cell lines, with no effect in the normal RWPE cells. In addition, MCP30 treatment increased the acetylation of histone-3 and 4 while total H3 and H4 levels remained unchanged in the same cell lines (Fig. 3a), suggesting that the bitter melon extract (MCP30) is a potential HDAC inhibitor that selectively increases histone acetylation in neoplastic prostate cell lines.

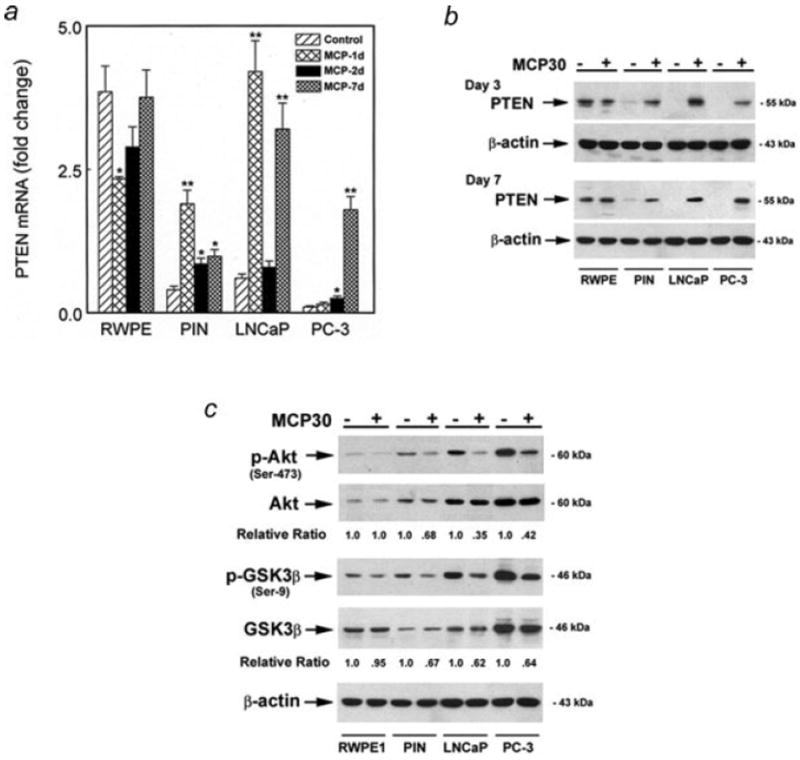

Figure 4.

MCP30 induces PTEN and inhibits Akt phosphorylation. Prostate-derived cell lines were treated with MCP30 (10 μg/ml) for the time period as indicated. (a) Quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of PTEN mRNA. Data are expressed as means ± SE of 3 wells from 3 separate experiments. *p < 0.01 as compared to control for each cell line. (b) Total Protein was extracted and subjected to Western blotting using antibody against PTEN. The same blot was stripped and sequentially reprobed with antibodies against β-actin. (c) MCP30 inhibits phosphorylation of Akt and GSK proteins. Total protein was extracted and subjected to Western blotting using antibody against phospho-Aktser473. The same blot was stripped and sequentially reprobed with antibodies against endogenous Akt, phospho-GSK3β, endogenous GSK3β and β-actin. Normalized quantification (relative ratio of PTEN to β-actin or the ratio of phospho-Akt or phospho-GSK to total Akt or GSK) of the immunoblots was performed by densitometry and is shown at the bottom. Data shown are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Figure 3.

MCP30 inhibits HDAC activity and induces acetylation of histone proteins. Prostate-derived cell lines were cultured in serum-free medium and treated with MCP30 (10 μg/mL) for 48 hr. (a) Protein in the nuclear fractions was extracted and subjected to Western blotting using antibody against HDAC-1. The same blot was stripped and sequentially reprobed with antibodies against acetyl-H3, H4, total H3, H4 and β-actin. Normalized quantification (relative ratio of acetylated H3 or H4 to total H3 or H4) of the immunoblots was performed by densitometry and is shown at the bottom. Data shown are representative of 3 separate experiments. (b) Protein in the nuclear fractions was extracted and subjected to HDAC activity assay. Data are expressed as means ± SE of 3 wells from 3 separate experiments. The HDAC activity in untreated RWPE cells is set as 100%, *p < 0.01 as compared to control for each cell line.

MCP30 induces PTEN expression and inhibits Akt phosphorylation

PTEN functional inactivation is strongly implicated in PCa development. Expression of functional PTEN inhibits Akt phosphorylation via the PI3-K pathway. Recent reports indicate that PTEN is upregulated at the transcriptional level by histone hyperacetylation.6,8 Based upon its effects on HDAC-1 expression and activity, we examined the effect of MCP30 on PTEN expression in PIN and PCa cell lines. As shown in Figure 4, normal prostatic epithelial cells (RWPE-1) expressed significant basal amounts of PTEN mRNA and protein. Initially, MCP30 treatment decreased both the mRNA (day 1, Fig. 4a) and protein levels (day 3, Fig. 4b) of PTEN in the RWPE cells but both mRNA and protein levels returned to baseline by day 7 of treatment. In contrast, basal levels of PTEN mRNA and protein were barely detectable in PIN cells and not expressed at all in the PCa cell lines basally and treatment with MCP30 significantly induced PTEN expression (at both the mRNA and protein levels) in PIN and PCa cell lines (Figs. 4a and 4b). Of note, the temporal changes in PTEN mRNA and protein expression after MCP30 treatment, varied among the cell lines. However, within each cell line, there was a good correlation between changes in PTEN mRNA (Fig. 4a) and protein (Fig. 4b) expression. For example, it required a minimum of 3 days of MCP30 treatment to induce PTEN at both the mRNA and protein levels in PC-3 cells and this effect was most pronounced after 7 days, again at both the mRNA and protein levels. In contrast, increased expression of both PTEN mRNA and protein in LNCaP cells was most pronounced at an earlier time period, 3 days after MCP30 treatment.

We next examined the intracellular events downstream of PTEN induction. Akt phosphorylation was significantly inhibited by MCP30 while total Akt expression remained unchanged in PIN and PCa cell lines. Consequently, the expression of phospho-GSK3β (Ser-9) was suppressed in the presence of MCP30 (Fig. 4c). These data imply that the tumor suppressor effect of MCP30 may be mediated by the induction of PTEN with subsequent suppression of one of its downstream targets, Akt, via dephosphorylation.

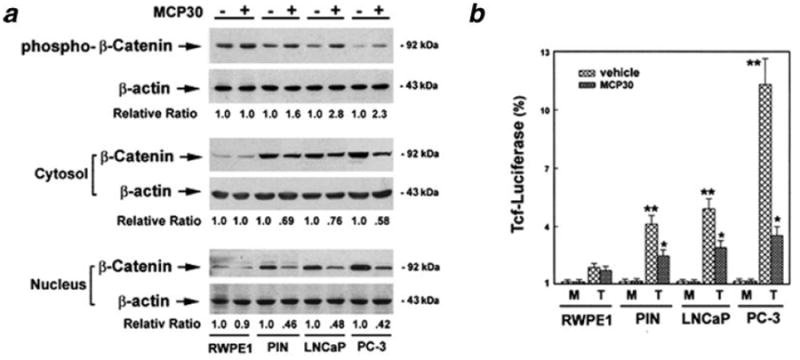

MCP30 inhibits Wnt signaling activity

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is regulated by the Akt pathway19,20 and suppressed by PTEN.21,22 A recent report suggests that Wnt transcriptional activity can be modulated by an HDAC inhibitor in human colorectal carcinoma cells.23 We next determined whether MCP30 modulates the intracellular levels and distribution of β-catenin, a key component of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. We used a specific antibody developed by Clevers et al. to detect active β-catenin triggered by the activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway.41 As shown in Figure 5a, nuclear β-catenin expression was barely detectable in RWPE cells and was not regulated by MCP30. In contrast, PIN and PCa cell lines demonstrated higher nuclear β-catenin expression levels. Treatment with MCP30 increased the expression of phospho-β-catenin protein, presumably resulting from increased GSK-3β activity, which promoted β-catenin degradation leading to decreased nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in these cell lines. This decrease in nuclear β-catenin was associated with suppression of Wnt signaling activity, as measured by Tcf-luciferase reporter assay, in the same cell lines (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

MCP30 inhibits activity of Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Prostate-derived cell lines were treated with MCP30 (10 μg/mL) for 48 hr. (a) Protein in the nuclear fractions was extracted and subjected to Western blotting using antibody against phospho-β-catenin. The same blot was stripped and reprobed with antibodies against β-catenin and β-actin antibodies. Normalized quantification (relative ratio of β-catenin to β-actin) of the immunoblots was performed by densitometry and is shown at the bottom. Data shown are representative of 3 separate experiments. (b) Cells were cotransfected with the Tcf reporter plasmid (or empty vector as mock control) and the β-galactosidase expression vector and treated with either vehicle or MCP30 (10 μg/mL) for 48 hr. The resulting Tcf-luciferase activity was normalized to protein concentrations and β-galactosidase activity. Data are expressed as fold-induction compared to the vehicle control (100%) and represent the means ± SE from 3 separate determinations. *p < 0.01 as compared to mock control (M) for each cell line; **p < 0.01 as compared to the levels of RWPE-1 cells.

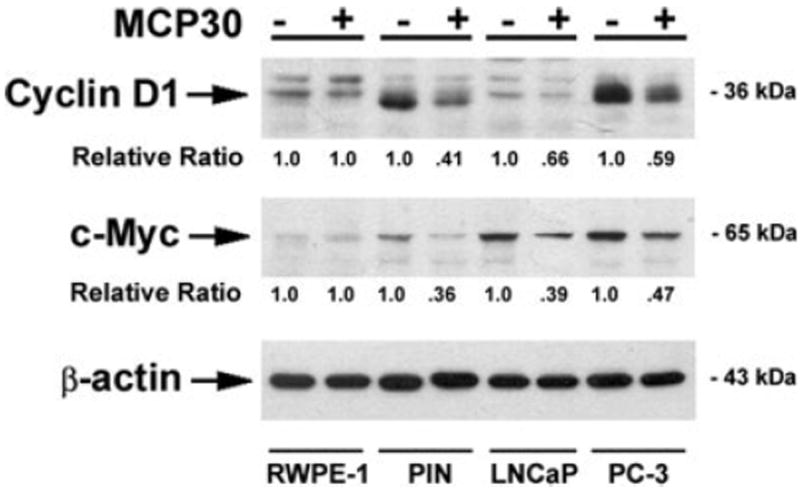

MCP30 modulates the expression of proteins controlling cell cycle progression and apoptosis

To further elucidate the effects of MCP30, we examined the expression of cyclin D1 and cMyc, proteins that are induced upon Wnt activation and are involved in controlling cell-cycle progression and apoptosis. Western blot analysis revealed that the expression levels of both proteins decreased after treatment with MCP30 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

MCP30 decreases the expression of Wnt-targeted proteins. Prostate-derived cell lines were treated with MCP30 (10 μg/mL) for 48 hr. Total Protein was extracted and subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies against cyclin D1. The same blot was stripped and sequentially reprobed with antibodies against c-Myc and β-actin. Normalized quantification (relative ratio of cyclin D or c-Myc to β-actin) of the immunoblots was performed by densitometry and is shown at the bottom. Data shown are representative of three separate experiments.

Discussion

Both dietary and environmental factors have been shown to induce epigenetic changes, i.e. mechanisms that permit stable transmission of cellular traits without an alteration in DNA sequence or amount. Epigenetic deregulation frequently participates in tumorigenesis through inactivation of tumor suppressor genes.15 Prostate cancer tends to be multifocal, suggesting a field effect that might be influenced by epigenetic changes due to diet and oxidative stress.42 Dietary compounds have also been shown to reverse these epigenetic changes31,43 and to be effective agents in the prevention and treatment of prostate cancer.25,26

The plant Momordica charantia (MC) or bitter melon grows in tropical Asia, where it is utilized both as a vegetable and medicinal herb. A 30kDa protein isolated from bitter melon seeds has demonstrated in vitro and in vivo anti-tumor activity in several tumor model systems.31,32,43 We have isolated a 30 kDa protein (MCP30) from bitter melon seeds. The purified fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and both the intensely silver-stained upper bands (~30 kDa) as well as the faint lower band (~22 kDa) were identified by mass spectrometry to contain 2 highly related ribosome-inactivating proteins (RIPs), α-momorcharin and β-momorcharin (MAP30). These 2 proteins have been reported to have similar biological activities, including N-glycosidase activity (cleaves the glycosidic bond between adenine and ribose in ribosomal RNA at a specific location34) and have also been shown to act on nucleic acids (e.g. intrinsic nuclease activities44). Although the precise mechanism of action of the Type I family of single chain ribosome-inactivating proteins is not well delineated, they are known to enter the cell through endocytosis27,45 and can induce apoptosis in cancer cells.46 The precise mechanisms whereby single-chain RIPS selectively enter viral-infected and malignant cells, induce apoptosis and exert selective effects on malignant cells have not been well delineated. Saporin, a Type I RIP from Saponaria officinalis (soapwort) induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in the human histiocytic lymphoma cell line U937 via the mitochondrial (intrinsic) pathway and this apoptotic activity occurs before the onset of any significant inhibition of protein synthesis.46 Trichosanthin (TCS), another Type I RIP, is highly toxic to choriocarcinoma JAR cells while hepatoma H35 cells are relatively resistant. Differences in receptor-mediated endocytotic uptake and intracellular routing of TCS were found between the 2 cell lines and higher accumulation in the choriocarcinoma JAR cells may explain their higher sensitivity to TCS.47

We tested the effects of MCP30 on cell growth and apoptosis in a variety of human prostate cell lines in vitro and demonstrate that it selectively induces both cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in premalignant and malignant prostate cells. Furthermore, in vivo administration of MCP30 decreased PC3 human prostate cancer cell growth subcutaneously in nude mice and this effect was due primarily to the induction of apoptosis, with no significant differences in markers of proliferation or MVD between control and treated animal tumors.

The selective induction of apoptosis in neoplastic cells is also a hallmark of a class of anti-tumor compounds known as HDAC inhibitors. HDACs, which catalyze the removal of acetyl groups from the N-terminus of histones, lead to chromatin condensation and transcriptional repression.15 Altered expression of individual HDACs in tumor samples has been reported48 and several HDAC inhibitors are in clinical trials for cancer therapy. We determined the effects of MCP30 on HDAC1 in prostate-derived cell lines because this particular HDAC was previously shown to be overexpressed in human premalignant and malignant prostate lesions, with the highest increase in expression in hormone refractory prostate cancer.11 We confirmed that HDAC1 activity is increased in premalignant and malignant prostate cancer cell lines as compared to the non-neoplastic RWPE cell line. Furthermore, our data demonstrate that that the Type I RIPs contained in MCP30 inhibit HDAC1 expression levels and activity selectively in the neoplastic cell lines.

Although many studies demonstrate that both HDACi and Type I RIPs can selectively kill tumor cells,14,32,46 the molecular pathways underlying these observed effects remain to be elucidated. HDAC inhibitors have been reported increase acetylation of non-histone proteins and may induce apoptosis through tumor specific induction of tumor suppressor and pro-apoptotic genes. As has been reported for other compounds that inhibit HDAC,14 MCP30 selectively increased tumor suppressor protein expression, including PTEN, KLF6 and E-cadherin (data not shown). This was not just a generalized effect on protein expression, as MCP30 did not modulate total protein levels of Akt, β-catenin or the β-actin housekeeping gene. We also present evidence that MCP30 may restore normal PTEN signaling as demonstrated by decreased activity of Akt by dephosphorylation at Ser-473, increased Ser-9 phosphorylation of GSK-3β, inhibition of canonical Wnt signaling and decreased expression of Cyclin-D1 and c-Myc in the neoplastic prostate cells. However, these events may be merely correlative and need to be further explored.

It was previously reported that 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, reactivates the transcription of PTEN in prostate cancer cells. More recently, the dietary compound genistein, was shown to induce PTEN expression in LNCaP and PC3 prostate cancer cells by inhibiting SIRT1, an HDAC that belongs to the atypical class III histone deacetylase family. Genistein activation involved demethylation and acetylation of H3-K9 at the PTEN promoter.49 Our data shows re-expression of PTEN mRNA and protein in PIN, LNCaP and PC3 cells which may result from the inhibitory effect of MCP30 on HDAC-1 levels and activity. Eighteen HDACs have been identified in humans and it is possible that MCP30, genistein and other dietary compounds modulate the expression and activity of multiple HDACs in a tissue-specific manner with resultant activation of a variety of tumor suppressor and pro-apoptotic genes.

A large number of structurally diverse HDACi have been purified from natural sources or synthetically developed and several of these are in clinical trials for cancer.15 Although most HDAC inhibitors are molecules of low molecular weight, maspin, a 42 kDa protein in the serine protease inhibitor family, was recently identified as an endogenous inhibitor of HDAC-1.50,51 To our knowledge, this is the first report that Type I ribosomal inactivating proteins derived from dietary bitter melon (Momordica charantia) possess HDACi activity and can selectively induce apoptosis in premalignant and malignant prostate cells and inhibit human prostate cancer cell growth in vivo. Our data imply that effective and non-toxic prostate cancer chemopreventive and therapeutic agents may be developed from plant-derived Type I ribosomal inactivating proteins.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. B. Vogelstein (John Hopkins Oncology Center, Baltimore, MD) for the TCF luciferase reporter construct and Dr. Mark Stearns (Department of Pathology, MCP-Hahnemann University, Philadelphia, PA) for the PC-3ML cell line. GN: Goutham Narla is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Physician-Scientist Early Career Awardee.

References

- 1.ACS. Cancer facts and figures. Atlanta, GA: ACS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakr WA, Ward C, Grignon DJ, Haas GP. Epidemiology and molecular biology of early prostatic neoplasia. Mol Urol. 2000;4:109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu X-H, Kirschenbaum A, Lu M, Yao S, Klausner A, Preston C, Holland JF, Levine AC. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia cell growth through activation of the interleukin-6/GP130/STAT-3 signaling pathway. Biochem Biophy Res Comm. 2002;290:249–55. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrams H, Spiro R, Godstein N. Metastases in carcinoma. Cancer. 1950;3:74–85. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<74::aid-cncr2820030111>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobs SC. Spread of prostatic carcinoma to bone. Urology. 1983;21:337–44. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(83)90147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamguney T, Stokoe D. New insights into PTEN. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:4071–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.015230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulholland DJ, Dedhar S, Wu H, Nelson CC. PTEN and GSK3β: key regulators of progression to androgen-independent prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:329–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan L, Lu J, Wang X, Han L, Zhang Y, Han S, Huang B. Histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A potentiates doxorubicin-induced apoptosis by up-regulating PTEN expression. Cancer. 2007;109:1676–88. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CS, Weng S-C, Tseng P-H, Lin H-P, Chen C-S. Histone acetylation-independent effect of histone deacetylase inhibitors on Akt through the reshuffling of protein phosphastase 1 complexes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38879–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505733200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin RJ, Sternsdorf T, Tini M, Evans RM. Transcriptional regulation in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Oncogene. 2001;20:7204–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halkidou K, Halkidou K, Gaughan L, Cook S, Leung HY, David E, Neal DE, Robson CN. Upregulation and nuclear recruitment of HDAC1 in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Prostate. 2004;59:177–89. doi: 10.1002/pros.20022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi JH, Kwon HJ, Yoon BI, Kim JH, Han SU, Joo HJ, Kim DY. Expression profile of histonce deacetylase I in gastric cancer tissues. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92:1300–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb02153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson AJ, Byun DS, Popova N, Murray LB, L’Italien K, Sowa Y, Arango D, Velcich A, Augenlicht LH, Mariadason JM. Histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) and other class I HDACs regulate colon cell maturation and p21 expression and are deregulated in human colon cancer. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13548–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandolfi PP. Histone deacetylases and transcriptional therapy with their inhibitors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001;48(Supp 1):S17–S19. doi: 10.1007/s002800100322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Anticancer activities of histone deactylase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:769–84. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruxvoort KJ, Charbonneua HM, Giambernardi TA, Goolsby JC, Qian C-N, Zylstra CR, Robinson DR, Roy-Burman P, Shaw AK, Buckner-Berghuis Sigler RE, Resau JH, Sullivan R, et al. Inactivation of Apc in the mouse prostate causes prostate carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2490–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nusse R. The Wnt gene homepage. 2005 Available at: http://www.stanford.edu/~rnusse/wntwindow.html.

- 18.Yang M, Waterman ML, Brachmann RK. hADA2a and hADA3 are required for acetylation, transcriptional activity and proliferative effects of β-catenin. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;7:120–28. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.1.5197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim E, Lee W-J, Choi K-Y. The PI3 kinase-Akt pathway mediates Wnt3a-induced proliferation. Cell Signal. 2007;19:511–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gang D, Hawke D, Zheng Y, Xia Y, Meisenhelder J, Nika H, Mills GB, Kobayashi R, Hunter T, Lu Z. Phosphorylation of β-catenin by AKT promotes β-catenin transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11221–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611871200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao H, Cui Y, Dupont J, Sun H, Henningausen L, Yakar S. Over-expression of the tumor suppressor gene phosphatase and tensin homologue partially inhibits Wnt-1-induced mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6864–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Persad S, Troussard AA, McPhee TR, Mulholand D, Dedhar S. Tumor suppressor PTEN inhibits nuclear accumulation of β-catenin and T cell/lymphoid enhancer factor-1 mediated transcriptional activation. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1161–73. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bordonaro M, Lazarova DL, Sartorelli AC. The activation of β-catenin by Wnt signaling mediates the effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:1652–66. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuhouser ML. Dietary flavonoids and cancer risk: evidence from human population studies. Nutr Cancer. 2004;50:107. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5001_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mentor-Marcel R, Lamartiniere CA, Eltoum IE, Greenberg NM, Elgavis A. Genistein in the diet reduces the incidence of poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinoma in transgenic mice (TRAMP) Cancer Res. 2001;61:6777–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shukla S, MacLennan GT, Flask CA, Fu P, Mishra A, Resnick MI, Gupta S. Blockade of β-catenin signaling by plant flavonoid apigenin suppresses prostate carcinogenesis in TRAMP mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6925–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee-Huang S, Huang PL, Nara PL, Chen H-C, Kung H, Huang H, Huang PL. MAP30: a new inhibitor of HIV-1 infection and replication. FEBS. 1990;272:12–18. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80438-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li SC. Pen Ts’ao Kang Mu (Chinese pharmaceutical compendium) Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grover JK, Yadav SP. Pharmacological actions and potential uses of Momordica charantia: a review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;93:123–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krawinkel MB, Keding GB. Bitter gourd (Momordica charantia): a dietary approach to hyperglycemia. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:331–7. doi: 10.1301/nr.2006.jul.331-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohno H, Yasui Y, Suzuki R, Hosokawa H, Miyashita K, Tanaka T. Dietary seed oil rich in conjugated linoleic acid from bitter melon inhibits azoxymethane-induced rat colon carcinogenesis through elevation of colonic PPARγ expression and alteration of lipid composition. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:896–901. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee-Huang S, Huang PL, Sun Y, Chen H-C, Kung H-F, Huang PL, Murphy WL. Inhibition of MDA-MD-231 human breast tumor xenografts and HER2 expression by anti-tumor agents GAP31 and MAP30. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:653–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang M, Liu A, Garcia FU, Rhim JS, Stearn ME. Growth of HPV-18 immortalized human prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia cell line, influence of IL-10, follistatin, activin-A and DHT. Int J Oncol. 1999;14:1185–95. doi: 10.3892/ijo.14.6.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barbieri L, Zamboni M, Lorenzoni E, Montanaro L, Sperti S, Stirpe F. Inhibition of protein synthesis in vitro by proteins from the seeds of Momordica charantia (bitter pear melon) Biochem J. 1980;186:443–52. doi: 10.1042/bj1860443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye GJ, Qian R, Lu B, Gu X, Jin S, Wang Q. Isolation, purification and charachterization of a protein from bitter malon seeds. Acta Chim Sinica. 1998;56:1135–44. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lam YW, Mobley JA, Evans JE, Carmody JF, Ho S-M. Mass profiling-directed isolation and identification of a stage-specific serologic protein biomarker of advanced prostate cancer. Proteomics. 2005;5:2927–38. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lam YW, Tam NC, Evans JE, Green KM, Zhang X, Ho S-M. Differential proteomics in the aging noble rat ventral prostate. Proteomics. 2008;8:2750–63. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu XH, Kirchenbaum A, Lu M, Yao S, Holland JF, Levine AC. Prostaglandin E2 induces hypoxia inducible factor-1α protein stabilization and nuclear localization in a human prostate cancer cell line. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50081–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201095200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rose DP, Connolly JM, Meschter CL. Effect of dietary fat on human breast cancer growth and metastasis in nude mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1491–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.20.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu XH, Kirschenbaum A, Yao S, Lee R, Holland JF, Levine AC. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 suppresses angiogenesis and the growth of prostate cancer in vivo. J Urol. 2000;164:820–25. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200009010-00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Staal FJ, Noort M, Strous GJ, Clevers HC. Wnt signals are transmitted through N-terminally dephosphorylated β-catenin. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:63–8. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dobosy JR, Roberts JLW, Fu VS, Jarrard DF. The expanding role of epigenetics in the development, diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2007;177:822–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yasui Y, Hosokawa M, Sahara T, Suzuki R, Ohgiya S, Cono H, Tanaka T, Miyashita K. Bitter gourd seed fatty acid rich in 9c,11t,13t-conjugated linolenic acid induces apoptosis and up-regulates the GADD45, p53 and PPARγ in human colon cancer Caco-2 cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;73:113–19. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fong WP, Mock WY, Ng TB. Intrinsic ribonuclease activities in ribonuclease and ribosome-inactivating proteins from the seeds of bitter gourd. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;32:571–7. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee-Huang S, Huang PL, Chen H, Huang PL, Bourinbaiar A, Huang HI, Kung H. Anti-HIV and anti-tumor activities of recombinant MAP30 from bitter melon. Gene. 1995;161:151–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00186-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sikriwal D, Ghosh P, Batra JK. Ribsome inactivating protein saporin induces apoptosis through mitochondrial cascade, independent of translation inhibition. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2880–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan WY, Huang H, Tam S-C. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of trichosanthin in choriocarcinoma cells. Toxicology. 2003;186:191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00746-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drummond DC, Nobel CO, Guo Z, Scott GK, Benz CC. Clinical development of histone deacetylase inhibitors as anti-cancer agents. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:495–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kikuno N, Shiina H, Urakami S, Kawamoto K, Hirata H, Tanaka Y, Majid S, Igawa M, Dahiya R. Genistein mediated histone acetylation and demethylation activates tumor suppressor genes in prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:552–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li X, Yin S, Meng Y, Sakr W, Sheng S. Endogenous inhibition of histone deacetylase1 by tumor-suppressive maspin. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9323–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khalkhali-Ellis Z. Maspin: The new frontier. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;24:7279–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]