Abstract

Central in a variational implicit-solvent description of biomolecular solvation is an effective free-energy functional of the solute atomic positions and the solute-solvent interface (i.e., the dielectric boundary). The free-energy functional couples together the solute molecular mechanical interaction energy, the solute-solvent interfacial energy, the solute-solvent van der Waals interaction energy, and the electrostatic energy. In recent years, the sharp-interface version of the variational implicit-solvent model has been developed and used for numerical computations of molecular solvation. In this work, we propose a diffuse-interface version of the variational implicit-solvent model with solute molecular mechanics. We also analyze both the sharp-interface and diffuse-interface models. We prove the existence of free-energy minimizers and obtain their bounds. We also prove the convergence of the diffuse-interface model to the sharp-interface model in the sense of Γ-convergence. We further discuss properties of sharp-interface free-energy minimizers, the boundary conditions and the coupling of the Poisson–Boltzmann equation in the diffuse-interface model, and the convergence of forces from diffuse-interface to sharp-interface descriptions. Our analysis relies on the previous works on the problem of minimizing surface areas and on our observations on the coupling between solute molecular mechanical interactions with the continuum solvent. Our studies justify rigorously the self consistency of the proposed diffuse-interface variational models of implicit solvation.

Keywords: solvation, solute molecular mechanics, implicit solvent, surface energy, van der Waals interaction, electrostatics, motion by mean curvature, sharp interface, diffuse interface, Γ-convergence

1 Introduction

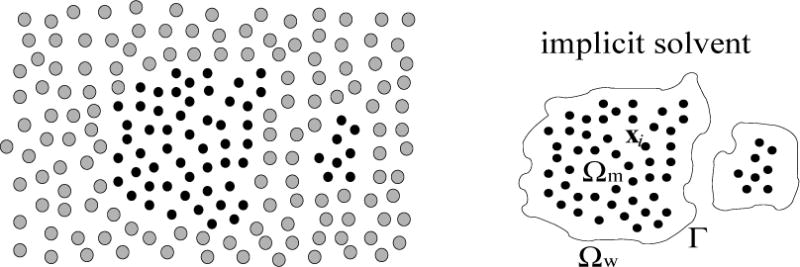

The interaction between biomolecules (such as proteins, nucleic acids, and lipid membranes) and their surrounding aqueous solvent (such as water or salted water) contributes significantly to the structure, dynamics, and functions of an underlying biomolecular system. Such interactions can be described efficiently by implicit-solvent (or continuum-solvent) models [19, 37]. In such a model, the solvent molecules and ions are treated implicitly and their effects are coarse-grained; cf. Figure 1. The description of the solvent is thus reduced to that of the solute-solvent interface (i.e., the dielectric boundary) and the related macroscopic quantities, such as the surface tension, dielectric coefficients, and bulk solvent density. Implicit-solvent models are complementary to the more accurate but also more expensive explicit-solvent models such as molecular dynamics simulations, which often provide sampled statistical information rather than direct thermodynamic descriptions.

Figure 1.

Schematic descriptions of a solvation system. Left: In a fully atomistic model, both the solute atoms (small and dark dots) and solvent molecules (large and grey dots) are degrees of freedom of the system. Right: In an implicit-solvent model, the solvent molecules are coarse-grained and the solvent is treated as a continuum. The solvent region Ωw and the solute region Ωm are separated by the solute-solvent interface (i.e., the dielectric boundary) Γ. The solute atoms are located at x1, …, xN inside Ωm.

With an implicit solvent, the conformation of a biomolecular system in equilibrium is described by all the atomic positions of solute molecules together with the solute-solvent interface. In the recently developed variational implicit-solvent model, such equilibrium solute atomic positions and solute-solvent interfaces are defined to minimize an effective free-energy functional; cf. [15, 16] and [11, 43] for more details. In a simple setting, the free-energy functional has the form

| (1.1) |

Here the first term E[X]is the potential energy of molecular mechanical interactions of solute atoms located at x1, …, xN inside the solute region Ωm (cf. Figure 1) and X = (x1, …, xN). The molecular mechanical interactions include the chemical bonding, bending, and torsion; the short-distance repulsion and the long-distance attraction; and the Coulombic charge-charge interaction.

The second term is an effective surface energy of the solute-solvent interface Γ that separates the solute region Ωm from the solvent region Ωw, where γ is an effective surface energy density assumed to be a constant. (The subscripts m and w stand for molecule and water, respectively.)

The last term models the solute-solvent interactions by an interaction potential U(X, x) that is defined on all (X, x) with ) and x ∈ Ωw. There are mainly two types of solute-solvent interactions. One is the non-electrostatic dispersive interaction that includes the repulsion due to the excluded-volume effect and the van der Waals attraction. Such interactions can be modeled by ρwUvdW, where ρw is the bulk solvent density and UvdW is the potential defined by

| (1.2) |

Here, each Ui (|x − xi|) is the interaction potential between the solute particle at xi and a solvent molecule or an ion located at x ∈ Ωw. Practically, one can take the pairwise interaction Ui to be a Lennard-Jones potential

with εi and σi being effective parameters. The other is the electrostatic interaction for which the solute-solvent interface Γ is used as the dielectric boundary. In an implicit-solvent approach, the electrostatic interaction energy is often obtained by solving the Poisson–Boltzmann equation [12, 21, 24, 31, 40]. However, by using the Coulomb-field or Yukawa-field approximation, we can obtain, without solving the Poisson–Boltzmann equation, good approximations of the electrostatic interaction energy [7, 43]. In the Coulomb-field approximation, the electrostatic energy density is given by [43]

where εv is the vacuum permittivity (often denoted by ε0 in literature), εm and εw are the relative permittivities of the solute and solvent, respectively, and Qi is the charge carried by the solute atom located at xi. (Typical values of εm and εw are around 1 and 80, respectively) The total solute-solvent interaction potential is then given by

| (1.3) |

For a fixed set of solute atoms X = (x1, …, xN), a solute-solvent interface Γ with a low free energy tends to minimize its surface area. On the other hand, the solute-solvent interaction modeled by the third term in (1.1) prevents the interface from being too close to the solute atoms located at xi (1 ≤ i ≤ N).

In [8], Cheng et al. developed a robust level-set method to minimize numerically the free-energy functional (1.1) for a fixed set of solute atoms X. The idea is to move an initially guessed solute-solvent interface that may have a large free energy in the direction of steepest descent of free energy until a (local) minimizer is reached. The “velocity” of the moving interface is therefore given by the effective interface or boundary force that is defined to be the negative variational derivative of the free-energy functional with respect to the location change of the interface. This method has been improved, generalized, and applied to many more systems ranging from small molecules to proteins [9–11, 38, 43]. Extensive numerical results with comparison with molecular dynamics simulations have demonstrated the success of the level-set variational solvation in capturing the hydrophobic interaction, multiple equilibrium states of hydration, and fluctuations between such states.

In this work, we first propose a diffuse-interface variational implicit-solvent model, as an alternative to the original variational implicit-solvent model that uses a sharp-interface formulation, for molecular solvation. We then prove that the diffuse-interface model converges to the corresponding sharp-interface model in the sense of Γ-convergence.

Diffuse-interface approaches have been widely used in studying interface problems arising in many scientific areas, such as materials physics, complex fluids, and biomembranes, cf. e.g., [1, 4, 5, 14, 17, 22, 25, 30, 39] and the references therein. In a diffuse-interface model, an interface separating two regions is represented by a continuous function that takes values close to one constant in one of the regions and another constant in the other region, but smoothly changes its values from one of the constants to another in a thin transition region. Both the sharp-interface and the diffuse-interface approaches have their own advantages and disadvantages. Existing studies have shown that interfacial fluctuations can be described in a diffuse-interface approach [3, 26]. Such fluctuations are particularly crucial in the transition of one equilibrium conformation to another in a biomolecular system.

Our diffuse-interface model is governed by the effective free-energy functional

| (1.4) |

Here ε > 0 is a small parameter. As in the sharp-interface variational solvation model, X = (x1, …, xN) and xi is the position of the ith solute atom (1 ≤ i ≤ N). All the solute atoms are located inside the entire solvation region Ω. The function ϕ : Ω → ℝ, often called an order parameter, describes the location of solute-solvent interface. The first term E[X] is the same as in the sharp-interface model; cf. (1.1). The second term is an approximation of the surface energy of the solute-solvent interface, where the parameter γ is the constant surface energy density as before and the function W = W(s) is a double-well potential with the two wells at s = 0 and s = 1 of equal depth. The last term is the solute-solvent interaction energy with the potential U(X, x) being the same as in the sharp-interface model; cf. (1.3).

To obtain numerically equilibrium conformations of a charged molecular system, we fix the small parameter ε > 0 and solve numerically the equations of the gradient-flow of the free-energy functional (1.4),

for X = X(t) and ϕ = ϕ(x, t). Here and below, a dot on top denotes the derivative with respect to t, ∇X denotes the gradient with respect to X = (x1, …, xN), and δϕ denotes the variational derivative with respect to ϕ. Explicitly, the gradient-flow equations are

| (1.5) |

The second equation is equivalent to the N vector-equations

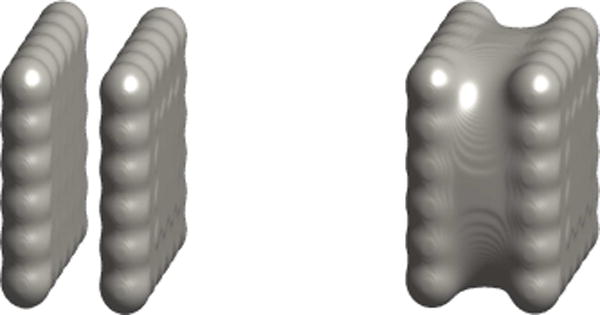

In Figure 2, we show our diffuse-interface computational results of a two-plate molecular system that has been used as a prototype system in many molecular dynamics and continuum simulations [8, 9, 28, 29, 33, 43]. Each plate consists of 6 × 6 neutral atoms that are fixed in each of the two computations. We observe that the diffuse-interface model captures the two local minimizers of the system. We shall report more diffuse-interface computational results in our subsequent work.

Figure 2.

Numerical computations of a two-plate system based on the diffuse-interface version of the variational implicit-solvent model. Left: a tight-wrap equilibrium conformation. Right: a dewetting equilibrium conformation.

The main body of this work is an analysis of the variational implicit-solvent models, both the sharp-interface and the diffuse-interface versions, for molecular solvation. Specifically, we prove the following:

The sharp-interface free-energy functional F = F[X, Γ], defined in (1.1), is minimized by a set of solute atoms X and the boundary of a measurable subset A ⊆ Ω that has a finite perimeter in Ω. Moreover, the minimum free energy can be approximated by boundaries of sets that contain small balls centered at xi (1 ≤ i ≤ N); cf. Theorem 2.1 and Theorem 2.2;

The existence of free-energy minimizers of the diffuse-interface free-energy functionals Fε, defined in (1.4), and the bounds on such minimizers and on the minimum free energies; cf. Theorem 3.1;

The convergence of the minimum free energies and the free-energy minimizers of the diffuse-interface free-energy functional (1.4) to those of the corresponding sharp-interface free-energy functional (1.1); cf. Theorem 4.1, Theorem 4.2, and Theorem 4.3.

In addition, we discuss several issues. These include the regularity and other properties of sharp-interface free-energy minimizers, the boundary conditions in the diffuse-interface model, the convergence of the diffuse-interface forces to the sharp-interface forces, and the coupling of the Poisson–Boltzmann description of the electrostatic interaction in the diffuse-interface modeling. We discuss both the forces acting on the solute atoms and the dielectric boundary forces.

Our analysis relies on some of the properties of the underlying models, in particular, the interplay between the solute particles X and the field ϕ, and on the existing studies on the diffuse-interface approximations of the motion by mean curvature with the constant-volume constraint [27, 34, 35, 41].

We notice that a diffuse-interface model for solvation is proposed in [6], where the surface energy is modeled by the integral of γ|∇S| with γ being the surface energy density and S a field similar to our ϕ. However, there are no terms in the total free-energy functional Gtotal (cf. Eq. (7) in [6]) that can keep the field S to be close to two distinct values so that the system region can be partitioned into the solute and solvent regions by the field S. Unless an equilibrium boundary or field S is a priori known, the minimization of the total free-energy functional will smooth out the field S to reduce the surface energy.

In Section 2, we describe the main assumptions on the interaction potentials E[X] and U(X, x). We also prove the existence of minimizers for the sharp-interface free-energy functional (1.1). In Section 3, we prove the existence of minimizers for the diffuse-interface free-energy functional (1.4). We also prove some properties of such minimizers. In Section 4, we prove the convergence of the minimum free energies and free-energy minimizers in passing the diffuse-interface to the sharp-interface description. Some lemmas are used in the proof. These lemmas are proved in the Appendix. Finally, in Section 5, we discuss several issues on the properties of sharp-interface free-energy minimizers, the boundary conditions, the convergence of forces, and the coupling of the Poisson–Boltzmann equation in the diffuse-interface modeling.

2 Sharp-Interface Free-Energy Minimizers

Let Ω be a nonempty, open, connected, and bounded subset of ℝ3 with a Lipschitz-continuous boundary ∂Ω. We use an overline to denote the closure of a set. So, is the closure of Ω in ℝ3. Let N > 1 be an integer and denote

Clearly ON is an open subset of (ℝ3)N. Let satisfy the following

-

Assumptions on E:

(E1) and E[X] is finite if X ∈ ΩN ⋂ ON. Moreover, the restriction of E onto ΩN ⋂ ON is a continuous function;

(E2) is finite;

(E3) E[X] → + ∞ as min1≤i<j≤N|xi − xj| → 0;

(E4) E[X] → + ∞ as min1≤i≤N dist (xi, ∂Ω) → 0.

The function E = E[X] with X = (x1, …, xN) models the potential of the molecular mechanical interactions among the solute atoms located at x1, …,xN. The assumption (E1) states that E[X] = + ∞ if two different atoms occupy the same position, i.e., xi = xj for some i and j with i ≠ j; or an atom is on the boundary, i.e., xi ∈ ∂Ω for some i. Part of the assumption (E1) and the assumption (E3) describe the repulsion of solute atoms. Part of the assumption (E1) and the assumption (E4) can be viewed as a consequence of the assumption that E[X] → + ∞ as , where is the geometrical center of the solute atoms. This models the connectivity of these atoms as a network. In practice, the open set Ω is an underlying computational region; and the solute atoms will be always kept inside Ω.

Let satisfy the following

-

Assumptions onU:

(U1) and U(X, x) is finite if . Moreover, the restriction of U onto is a continuous function;

(U2) is finite;

(U3) U(X, x) → +∞ as min0≤i<j≤N|xi − xj|→0, where x0 = x.

The function U = U(X, x) describes the solute-solvent interactions. Part of the assumption (U1) and the assumption (U3) model the repulsion in such interactions.

We recall that a function f ∈ L1 (Ω) is said to have bounded variations in Ω, if

| (2.1) |

where denotes the space of all C1-mappings from Ω to ℝ3 that are compactly supported inside Ω; cf. [18, 23, 44]. If f ∈ W1,1(Ω) then the value defined by (2.1) is the same as . The space BV(Ω) of all L1(Ω)-functions that have bounded variations in Ω is a Banach space with the norm

For any A ⊆ ℝ3, we denote by χA the characteristic function of A : χA(x) = 1 if x ∈ A and χa(x) = 0 if x ∉ A. If A is Lebesgue measurable, then the perimeter of A in Ω is defined by [18, 23, 44]

We denote

Let γ > 0 be given. For any (X, A) ∈ M0, we define

| (2.2) |

Since E and U are bounded below, F0(X, A)> −∞. If A ⊂ Ω is open and smooth, with a finite perimeter in Ω, then F0(X, A) = F(X, Γ), where Γ = ∂A and F is defined in (1.1) with Ωw = Ω\A. Therefore, F0 : M0 → ℝ∪ {+∞} describes the free energy of a solvation system with A being the solute region.

We denote by B(y, r) the open ball in ℝ3 centered at y ∈ ℝ3 with radius r > 0. For convenience in the analysis of the solute effect, we introduce the following

Definition 2.1

Let X = (x1, …, xN) ∈ ΩN ∩ ON and σ > 0. We call a σ-core of X in Ω associated with the potential U (X, ⋅), or simply an X-core, if the following are satisfied: (1) B(X, σ) ⊆ Ω; (2) if i ≠ j; and (3) U(X, x) ≥ 0 for all x ∈ B(X, σ).

It follows from the assumption (U3) that B(X, σ) is an X-core if X ∈ ΩN ∩ ON and σ > 0 is sufficiently small.

Our first theorem asserts the existence of a global minimizer of the sharp-interface free-energy functional F0:M0 → ℝ ∪ {+∞}. This is a standard result and can be proved by the direct methods in the calculus of variations. To show how the solute atoms located at x, …, xN can be analyzed, here we give a complete proof of the theorem.

Theorem 2.1

There exists (X, A) ∈ M0 such that

Moreover, this minimum value is finite.

Proof

Let . Since E and U are bounded below, α > −∞. Fix X0 G ΩN∩ ON. Let A0 = B(X0, σ) be an X0-core. Then (X0, A0) ∈ M0. Note that U(X0, ⋅) is bounded on . Hence F0[X0, A0] < ∞; and α is finite. There now exist (Xk, Ak) ∈ M0 (k = 1, 2, …) such that limk→∞F0[Xk, Ak] = α and that F0[Xk, Ak] is finite for each k ≥ 1. The lower boundedness of E and U implies that is bounded. This further implies that the sequence

is bounded, and finally that is bounded.

Since is bounded, it has a subsequence, not relabeled, such that Xk → X as k → ∞ for some . It follows from the boundedness of and our assumptions on E that X ∈ ΩN ∩ ON. Moreover, the continuity of E at X implies that

| (2.3) |

By the boundedness of and the compact embedding BV(Ω)↪L1 (Ω), there exists a subsequence of {χAk}, not relabeled, such that χAk → χa in L1 (Ω) for some Lebesgue measurable set A ⊆ Ω. Moreover,

| (2.4) |

Clearly (X, A) ∈ M0. Passing to a further subsequence of if necessary, we may assume that χAk → χA a.e. in Ω. Applying Fatou’s Lemma and using the fact that χAk → χa in L1 (Ω), we obtain

| (2.5) |

Now (2.3), (2.4), and (2.5) imply

Hence F0[X, A] = α. Q.E.D.

We now prove that the minimum value of the free-energy functional F0 : M0 → ℝ∪ {+∞} can be approximated by free energies of certain “regular” subsets. To this end, we denote by A0 the class of subsets E∩Ω such that

E is an open subset of ℝ3 with a nonempty compact, C∞ boundary ∂E;

∂E ∩ Ω is C2;

H2(∂E ∩ ∂Ω) = 0.

Here and below H2(S) denotes the 2-dimensional Hausdorff measure of a set S ⊆ ℝ3. We denote

| (2.6) |

Theorem 2.2

We have

| (2.7) |

To prove this theorem, we need two lemmas. We denote by σk ↓ 0 to mean that σ1 >…> σk>… and limk→∞σk = 0.

Lemma 2.1

Let (X, A) ∈ M0. Let σk > 0 (k = 1, 2, …) be such that σk ↓ 0 and that B(X, σk) (k = 1, 2, …) are all X-cores. We have

| (2.8) |

Proof

If F0[X, A] = ∞ then (2.8) is true. Assume F0[X, A] < ∞. Since both E and U are bounded below, this implies that PΩ(A) < ∞. Moreover,

| (2.9) |

It is easy to verify that for each k ≥ 1 that

Since U(X, x) ≥ 0 for all x ∈ B(X, σk) for each k ≥ 1, we then have

This, (2.9), and (2.2) (the definition of F0) imply (2.8) Q.E.D.

Lemma 2.2

Let (X, A) ∈ M0 be such that X ∈ ΩN ∩ ON, PΩ(A) < ∞, and A contains an X-core. Then for each integer k ≥ 1 there exists Ak ⊆ A0 such that Ak contains an X-core, and

| (2.10) |

This lemma is very similar to Lemma 1 in [34] and Lemma 1 in [41]. The volume constraint there, which gives rise to rather technical difficulties, is replaced here by the integral term in the free-energy functional F0.

Proof of Lemma 2.2

Assume A contains an X-core B(X, σ). Since PΩ(A)< ∞, there exists u ∈ BV (ℝ3) ∩ L∞(ℝ3) such that u = χA in Ω and

| (2.11) |

cf. (3) in [34]. Notice that u = 1on B(X, σ). By using mollifiers, we can construct uk ∈ C∞(ℝ3) (k = 1, 2, …) such that uk = 1 in B(X, σ/2) (k = 1, 2, …), uk → u in L1(Ω), and using (2.11)

cf. Sections 2.8 and 2.16 in [23]. For a given t ∈ ℝ, we define Ek = {x ∈ ℝ3: uk(x) > t} (k = 1, 2, …). Clearly, each Ek is an open subset of ℝ3. Following the proof of Lemma 1 in [34] and Lemma 1 in [41], there exists t ∈ (0, 1) and a subsequence of , not relabeled, that satisfy the following properties: (1) For each k ≥ 1, Ek ⊇ B(X, σ/2); (2) For each k, the boundary ∂Ek is nonempty, compact, and C∞; and ∂Ek ∩ Ω is C2; (3) For each k ≥ 1, H2(∂Ek ∩ ∂Ω) = 0; (4) χEk∩Ω → χA in L1(Ω) as k → ∞; and (5) PΩ(Ek ∩ A) → PΩ(A) as k → ∞.

Let Ak = Ek ∩ Ω (k = 1, 2, …). Clearly, for each k≥1, Ak ∈ A0 and Ak contains the X-core B(X, σ/2). Since U (X, ⋅) is bounded on , we have by the fact that χAk → χa in L1(Ω) that

This and the fact that PΩ(Ak) → PΩ(A) as k → ∞ imply (2.10). Q.E.D.

We are now ready to prove Theorem 2.2.

Proof of Theorem 2.2

Clearly,

By Theorem 2.1, the infimum of F0 over M0, which is finite, is attained by some (X0, A0) ∈ M0. Clearly, X0 ∈ ΩN∩ ON and PΩ(A0) < ∞. Let B(X0, σk) (k = 1, 2, …) be X0-cores with σk ↓ 0. It follows from Lemma 2.1 that

leading to

| (2.12) |

For each k ≥ 1, the set A0 ∪ B(X0, σk) has a finite perimeter in Ω. Therefore, by Lemma 2.2, there exists Ak ∈ A0 containing an X0-core, such that

This and (2.12) imply (2.7), since (X0, Ak) ∈ R0 (k = 1, 2, …). Q.E.D.

3 Diffuse-Interface Free-Energy Minimizers

We define W:ℝ → ℝ by

Note that

| (3.1) |

Let ε0 ∈ (0, 1). Let . By the lower boundedness of the functions E and U, Fε[X, ϕ] > −∞ for any (X,ϕ) ∈ M and any ε ∈ (0,ε0], where Fε[X, ϕ] is defined in (1.4). We consider the family of functional Fε: M → ℝ ∪ {+∞} (0 < ε ≤ ε0).

Theorem 3.1

For each ε ∈ (0,ε0], there exists (Xε, ϕε) ∈ M with Xε ∈ ΩN ∩ ON such that

| (3.2) |

and this infimum value is finite. Moreover, there exist constants C1and C2such that

| (3.3) |

If (Xε, ϕε) ∈ M satisfies (3.2) for each ε ∈ (0, ε0], then

| (3.4) |

Moreover, there exists a constant C3such that

| (3.5) |

The following lemma provides a lower bound of the functional Fε (0 < ε ≤ ε0); it will be used in the proof of Theorem 3.1 and other results:

Lemma 3.1

There exists C4 ∈ ℝ such that

Proof

Let (X, ϕ) ∈ M. We have

where

Notice that g: ℝ → ℝ is continuous and g(s) → + ∞ as |s| → + ∞. The desired bound is now obtained by setting C4 = Emin + |Ω| infs∈ℝg(s). Q.E.D.

Proof of Theorem 3.1

Fix ε ∈ (0, ε0]. Let β = inf(X,ϕ)∈ΜFε[X,ϕ]. Fix X ∈ ΩN∩ON and define ϕ(x) = 1 for all x ∈ Ω. Then (X,ϕ) ∈ M and Fε[X,ϕ] = E[X]which is finite. Hence β < + ∞. By Lemma 3.1, β > −∞. Therefore β is finite. It now follows that there exist (Xk, ϕk) ∈ M (k = 1, 2, …) such that Fε[Xk,ϕk] → β as k → ∞ and that Fε[Xk, ϕk] is finite for each k ≥ 1. By Lemma 3.1 and the lower boundedness of E and U, all the sequences ,

(k = 1, 2, …) are bounded.

Since is bounded in (ℝ3)N, it has a subsequence, not relabeled, that converges to some . By the boundedness of and our assumptions on E, Xε ∈ ΩN ∩ ON. Since is bounded in H1 (Ω), there exist ϕε ∈ H1 (Ω) and a subsequence of , not relabeled, such that ϕk ⇀ ϕε (weak convergence) in H1(Ω), ϕk → ϕε in L2 (Ω), and ϕk → ϕε a.e. in Ω. The weak convergence ϕk ⇀ ϕε in H1 (Ω) implies that

By the continuities of E and U in their respective regions and Fatou’s Lemma, we have

This proves (3.2).

The lower bound in (3.3) follows from Lemma 3.1. Thus we need only to prove the upper bound in (3.3). Fix . Let be an X*-core with σ ∈ (0, ε0). Let ε ∈ (0, σ]. Define hε:[0, 2σ] → ℝ by

Define by

Clearly ). Moreover, we have using the spherical coordinates that

| (3.6) |

Since on B(X*,σ) and U(X*, ⋅) is bounded on , we have

| (3.7) |

For each ε ∈ (σ, ε0], we define . It follows from (3.6) that

| (3.8) |

Setting

which is independent of ε ∈ (0, ε0], we obtain the upper bound in (3.3) by (1.4) (the definition of Fε), (3.6), (3.8), and (3.7) (which includes the case that ε = σ).

Assume now ε ∈ (0, ε0] and (Xε, ϕε) ∈ M satisfies (3.2). Denote by |S| the Lebesgue measure of a Lebesgue measurable subset S of ℝ3. Assume |{x ∈ Ω : ϕε(x) > 1}| > 0. Define

Clearly, . Moreover, and . If ϕε(x) > 1 then and . Hence on {x ∈ Ω : ϕε(x) > 1}. Consequently, . This contradicts (3.2). Therefore, (3.4) holds true.

Finally, the inequality (3.5) follows from (3.3), Lemma 3.1, and the lower boundedness of E and U.Q.E.D.

4 Convergence of Minimum Free Energies and Free-Energy Minimizers

We first prove the convergence of the global minimum free energies and the global free-energy minimizers.

Theorem 4.1

Let εk ∈ (0, ε0] (k = 1, 2, …) be such that εk ↓ 0. For each k ≥ 1, let be such that

| (4.1) |

Then there exists a subsequence of , not relabeled, such that in (ℝ3)N for some X0 ∈ ΩN ∩ ON and in L4−k (Ω) for any λ ∈ (0, 1) and for some measurable subset A0 ⊆ Ω that has a finite perimeter in Ω. Moreover,

| (4.2) |

and

| (4.3) |

To prove this theorem, we need two lemmas. These lemmas provide the liminf and limsup conditions that are essential for the Γ-convergence of the diffuse interfaces to the sharp interfaces. The proofs of these lemmas are given in the Appendix.

Lemma 4.1

Let εk ∈ (0, ε0] (k = 1, 2, …) be such that εk ↓ 0. Let satisfy

| (4.4) |

Then there exist a subsequence of , not relabeled, a point X0 ∈ ΩN ∩ ON, and a measurable set A0 ⊆ Ω with a finite perimeter in Ω such that, as k → ∞, in (ℝ3)N and in L4−λ(Ω) for any λ ∈ (0, 1). Moreover,

| (4.5) |

We recall that R0 is defined in (2.6).

Lemma 4.2

Let (X, A) ∈ R0. Let εk ∈ (0, ε0] (k = 1, 2, …) with εk ↓ 0. Then there exist such that in Lp (Ω) for any p ∈ [1, ∞) as k → ∞ and

| (4.6) |

We are now ready to prove Theorem 4.1.

Proof of Theorem 4.1

By Theorem 3.1, the sequence is bounded. By Lemma 4.1, there exists a subsequence of , not relabeled, a point X0 ∈ ΩN ∩ ON, and a measurable set A0 ⊆ Ω with a finite perimeter in Ω such that, as k → ∞, in (ℝ3)N and in L4−λ(Ω) for any λ ∈ (0, 1). Moreover,

| (4.7) |

Let (X, A) ∈ R0. It follows from Lemma 4.2 that, for the sequence εk↓ 0, there exist (hence such that

| (4.8) |

It now follows from (4.7), (4.1), and (4.8) that

Since (X, A) ∈ R0 is arbitrary, this, (4.1), and Theorem 2.2 imply that

| (4.9) |

Hence (4.3) is true. Finally, passing to a further subsequence of if necessary, we can replace in (4.9) the liminf by the lim to obtain (4.2). Q.E.D.

We now describe our results in terms of Γ-convergence. Such convergence will imply an additional result on the convergence of diffuse-interface local minimizers to a sharp-interface local minimizer. We first need to extend the functionals F0 and Fε to and , respectively, so that all the new functionals are defined on the same space. We define by

We also define for each ε ∈ (0, ε0] by

Theorem 4.2

Let ε ∈ (0, ε0] (k = 1, 2, …) be such that εk ↓ 0. Then the sequence of functionals Γ-converge to with respect to the metric of (ℝ3)N × L1 (Ω).

The Γ-convergence of to in (ℝ3)N × L1(Ω) means that the following two conditions are satisfied:

- If in (ℝ3)N × L1 (Ω), then

- For any , there exist such that

Proof of Theorem 4.2

This follows from Lemma 4.1 and Lemma 4.2 together with some simple arguments. Q.E.D.

Let ε ∈ (0, ε0] or ε = 0. We call an isolated local minimizer of , if there exists η > 0 such that for any with

Theorem 4.3

Let (X, ϕ) be an isolated local minimizer of . Let εk ∈ (0, ε0] (k = 1, 2, …) with εk ↓ 0. Then there exist such that, for each is a local minimizer of , and in as k → ∞.

Proof

This follows from Theorem 4.2 and the general theory of Γ-convergence, or from those arguments given in [27]. Q.E.D.

5 Discussions

5.1 Properties of sharp-interface free-energy minimizers

For simplicity, let us fix the set of solute atoms X = (x1, …, xN) ∈ ΩN∩ON and consider the sharp-interface free-energy functional F0[X, A], defined in (2.2), as a functional of all measurable sets A ⊆ Ω. We expect that a global or local minimizer A of this functional to be regular and to contain an X-core. The regularity of A should be similar to that of a minimal surface; cf. e.g., [23]. The important property that A contains an X-core, which has been always true numerically [8, 9, 11, 43], can be related to the following stronger but still realistic assumption: there exists σ0 > 0 such that for any σ ∈ (0, σ0)

More detailed analysis on the diffuse-interface free-energy minimizers can possibly help prove the property that a sharp-interface minimizer A contains an X-core.

5.2 Boundary conditions

In solving the systems of equations of the gradient flow (1.5), one would like to impose the homogeneous Dirichlet boundary condition ϕ = 0 on ∂Ω, since the solvent region is described by ϕ ≈ 0. With such a boundary condition, we need to redefine the diffuse-interface free-energy functional by

The Γ-limit with respect to the metric of (ℝ3)N× L1 (Ω) of any sequence of functional , where εk ∈ (0, ε0] (k = 1, 2, …) are such that εk↓ 0, is which is now defined by

where ; see [35]. (Note that in [35] the coefficient of the gradient-squared term in the energy functional is ε, not ε/2.) In numerical computations, the steady-state solution ϕ to the system of equations (1.5) often vanishes at the boundary ∂Ω. For such ϕ, the additional integral term in the Γ-limit then vanishes.

5.3 Convergence of forces

There are two different types of forces in a solvation system that can be described by variational implicit-solvent models. One is the force acting on the solute atoms located at x1, …, xN. The force acting on xi is defined to be for the sharp-interface model and with ε ∈ (0, ε0] for the diffuse-interface model. Let us assume that the potentials E and U are continuously differentiable in their respective domains of finite values. Based on formal calculations, we denote

If the integrals exist, then these 3N-component vectors represent the forces acting on X = (x1, …, xN) in the sharp-interface and diffuse-interface descriptions, respectively. Note that the surface energy terms in F0 and Fε do not contribute to the forces acting on solute atoms. Intuitively, we shall have the convergence that fε → f0 in some sense as ε → 0. But one needs to identify conditions under which such convergence holds.

Another type of force is the dielectric boundary force. In the sharp-interface model governed by the free-energy functional F[X, Γ] that is defined in (1.1), the dielectric boundary force—more precisely the normal component of the effective dielectric boundary force—is defined as −δΓF[X, Γ], the negative variational derivative of the free energy with respect to the location change of the dielectric boundary Γ. The variational derivative δΓF[X, Γ] is a function defined on Γ. It is known that for any fixed X ∈ ΩN ∩ ON[8, 11, 43]

| (5.1) |

where H = H(x) is the mean curvature at x ∈ Γ. See also [32] for the formula of the dielectric boundary force when the full coupling of the electrostatics using the Poisson–Boltzmann equation is used.

It is now natural to ask if the corresponding diffuse-interface forces will converge to the sharp-interface ones. The variation with respect to the field ϕ of the diffuse-interface free-energy functional Fε defined in (1.4) is

assuming the smoothness of ϕ, where X ∈ ΩN ∩ ON is fixed. This variation is a function defined on the entire region Ω. Suppose that εk ∈ (0, ε0] (k = 1, 2, …) are such that εk↓ 0 and are such that in L2(Ω) for some smooth open set A ⊂ Ω. We then expect that the related γ-terms,

will converge in some sense to −γH∂A with H∂A being the mean curvature of the boundary of A. This is intuitively true. But we are not aware of a proof in the literature.

For the related U-terms, we have that in Ω, which is totally different from the last term in (5.1). We notice that the variational derivative (5.1) is that of the free-energy functional F[X, Γ] with respect to the variation of the boundary Γ, not the variational derivative of the functional F0[X, A], which is defined in (2.2), with respect to the variation of the set A. It is therefore desirable to define and obtain a formula of the variational derivative δAF0[X, A]. It is also interesting to design a new form, if necessary and possible, to replace the U-term in the diffuse-interface free-energy functional so that all the energies, forces (with a suitable definition), and interfaces will converge correctly to the corresponding sharp-interface quantities.

5.4 Coupling the Poisson-Boltzmann equation

A more accurate description of the electrostatic interaction in a charged molecular system is to use the Poisson–Boltzmann equation for the electrostatic potential ψ[12, 21, 24, 31, 40]

together with some boundary conditions. Here Γ is the dielectric boundary that separates the solute region Ωm from the solvent region Ωw; cf. Figure 1, εΓ is the variable dielectric coefficient equal to one constant value εm in Ωm and another εw in Ωw, X = (x1, …, xN), ρX is the fixed charge density that consists of point charges Qi at the solute atoms xi(i = 1, …, N). Such point charges can often be approximated by smooth functions. The term −V′(ψ) is the density of charges of the mobile ions in the solvent, determined by the Boltzmann distribution. The function χw is the characteristic function of the solvent region Ωw. Once the electrostatic potential ψ is known, the electrostatic free energy is then determined as

To couple the Poisson–Boltzmann equation in the diffuse-interface model, we propose the following free-energy functional

| (5.2) |

in which the electrostatic potential ψ is determined by the diffuse-interface version of the Poisson–Boltzmann equation

| (5.3) |

together with some boundary conditions. In (5.2), ρw is the constant, bulk solvent density and UvdW is solute-solvent interaction potential defined in (1.2). In (5.2) and (5.3),

We shall present more details of this diffuse-interface model and report our related numerical simulations of molecular systems in our subsequent work.

It is now natural to ask if the free-energy functional Fε, defined in (5.2), and its related quantities, such as the free-energy minimizers, minimum free-energy values, forces, and the electrostatic potentials, will converge to their sharp-interface counterparts as ε → 0.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US National Science Foundation (NSF) through the grant DMS-0811259, the NSF Center for Theoretical Biological Physics (CTBP) through the grant PHY-0822283, and the National Institutes of Health through the grant R01GM096188 The authors thank Mr. Timonthy Banham, Dr. Jianwei Che, and Dr. Yuen-Yick Kwan for many helpful discussions.

Appendix

We now prove Lemma 4.1 and Lemma 4.2. Our proofs are based on the previous works [2, 13, 34–36, 41, 42]. For completeness, we give all the necessary details.

Proof of Lemma 4.1

We have by Lemma 3.1 and (4.4) that

| (A.1) |

Hence is bounded in L2(Ω). It then follows from (4.4) and the fact that

that is bounded. Since is bounded, it has a subsequence, not relabeled, that converges to some . By the boundedness of and our assumptions on E, we must have X0∈ΩN∩On.

Define G:ℝ → ℝ by

Direct calculations lead to

Therefore,

| (A.2) |

For each k ≥ 1, we define by for all x ∈ Ω. It follows from (A.1), (A.2), and Hölder’s inequality that is bounded in L4/3(Ω). Moreover,

| (A.3) |

This and (A.1) imply that is bounded in L1(Ω). Therefore, is bounded in W1,1 (Ω). By the compact embedding W1,1 (Ω) ↪ L1 (Ω), there exists a subsequence of , not relabeled, such that in L1 (Ω) and a.e. in Ω for some ψ0 ∈ L1 (Ω).

Note that G : ℝ → ℝ is bijective and its inverse G−1 : ℝ → ℝ is continuous. Set ϕ0 = G−1(ψ0) : Ω → ℝ. Clearly ϕ0 is measurable. By the definition of , we have . The continuity of G−1 implies that a.e. in Ω. By (A.1), as k → ∞. Fatou’s Lemma then implies that

Since W is continuous, W ≥ 0, and W = 0 only at 0 and 1, we have ϕ0 = χA0 a.e. in Ω for some measurable set A0 ⊆ Ω.

Let η > 0. Since a.e. in Ω, Egoroff’s Theorem asserts that there exists a measurable subset Ωη ⊆ Ω such that |Ω − Ωη| < η and uniformly on Ωη. Fix λ ∈ (0, 1). We have by Hölder’s inequality that

This, (A.1), and the uniform convergence on Ωη imply that

Since η > 0 is arbitrary, we obtain that in L4−λ(Ω).

Since ϕ0 = χA0, we have by (3.1) that

Therefore

Noting that PΩ (Ω) = 0, we then obtain by the Fleming–Rishel formula [20] that

| (A.4) |

On the other hand, since in L1 (Ω), we have

Together with (A.3), (A.4), and (A.1), this implies that

| (A.5) |

Since a.e. in a.e. x ∈ Ω, and in L2 (Ω), we obtain by Fatou’s Lemma that

| (A.6) |

Now the desired inequality (4.5) follows from the definition of Fε and F0, the fact that , (A.5), and (A.6). Q.E.D.

Proof of Lemma 4.2

We shall consider all ε ∈ (0, ε0] instead of . For each ε ∈ (0, ε0], we define qε : [0, 1] → ℝ by

Clearly, qε is a strictly increasing function of t ∈ [0, 1] with qε(0) = 0. Denote . Let pε : [0, λε] → [0, 1] be the inverse of qε : [0, 1] → [0, λε]. By using the formula of derivatives of inverse functions, we obtain

| (A.7) |

We extend pε onto the entire real line by defining pε(s) = 0 for any s < 0 and pε(s) = 1 for any s > λε.

Since (X, A) ∈ R0, A ∈ A0 and A contains an X-core. Thus A = E ∩ Ω for some open subset E of ℝ3 with a nonempty, compact, and C∞ boundary ∂E, such that ∂E ∩ Ω is C2 and H2(∂E ∩ ∂Ω) = 0. We define ϕ : Ω → ℝ by

where d : ℝ3 → ℝ is the signed distance function associated with the set E, defined by

Clearly, ϕε ∈ W1,∞ (Ω). Moreover, ϕε(x) = 1 if x∈A = E ∩ Ω,ϕε(x) = 0 if x ∈ Ω \ A and dist (x, ∂E) ≥ λε, and 0 ≤ ϕε(x) ≤ 1 if x ∈ Ω \ A and dist (x, ∂E) < λε.

Let p ∈ [1, ∞). We prove that ϕε → χA in Lp (Ω). Define p0 : ℝ → ℝ by p0(s) = 0 if s < 0 and p0(s) = 1 if s ≥ 0. We have then χE(x) = 1 − p0(d(x)) for any x ∈ ℝ3\∂E. Since ∂E ∩ Ω is in C2, we have χA(x) = 1 − p0(d(x)) a.e. x ∈ Ω. It now follows from the co-area formula that

Since H2(∂E ∩ ∂Ω) = 0, ∂E is smooth, and A = E ∩ Ω, we have (cf. Lemma 4 in [34], Lemma 2 in [41], and (1.1) in [23])

| (A.8) |

Consequently ϕε → χA in Lp (Ω).

We now prove (4.6). Applying the co-area formula and using the symmetry W(1 − s) = W(s) for any s ∈ ℝ, we obtain

| (A.9) |

It follows from (A.7), the change of variables t = pε(s), and (3.1) that

Combining this, (A.8), and (A.9), we obtain

| (A.10) |

Notice that U(X, ⋅) is continuous and bounded on , since A ⊇ B(X, σ). Since ϕε = 1 on A for all ε ∈ (0, ε0] and ϕε → χA in L2 (Ω) as ε → 0, we obtain that

Contributor Information

Bo Li, Email: bli@math.ucsd.edu.

Yanxiang Zhao, Email: y1zhao@ucsd.edu.

References

- 1.Anderson DM, McFadden GB, Wheeler AA. Diffuse-interface methods in fluid mechanics. Ann Rev Fluid Mech. 1998;30:139–165. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellettini G, Mugnai L. Approximation of Helfrich’s functional via diffuse interfaces. SIAM J Math Anal. 2010;42:2402–2433. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benítez R, Ramírez-Piscina L. Sharp-interface projection of a fluctuating phase-field model. Phys Rev E. 2005;71:061603. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.061603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boettinger WJ, Warren JA, Beckermann C, Karma A. Phase-field simulation of solidification. Annu Rev Materials Res. 2002;32:163–194. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen LQ. Phase-field models of microstructure evolution. Annu Rev Materials Res. 2002;32:113–140. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Z, Baker NA, Wei GW. Differential geometry based solvation model I: Eulerian formulation. J Comput Phys. 2010;229:8231–8258. doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng HB, Cheng LT, Li B. Yukawa-field approximation of electrostatic free energy and dielectric boundary force. Nonlinearity. 2011;24:3215–3236. doi: 10.1088/0951-7715/24/11/011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng LT, Dzubiella J, McCammon JA, Li B. Application of the level-set method to the implicit solvation of nonpolar molecules. J Chem Phys. 2007;127:084503. doi: 10.1063/1.2757169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng LT, Li B, Wang Z. Level-set minimization of potential controlled Hadwiger valuations for molecular solvation. J Comput Phys. 2010;229:8497–8510. doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng LT, Wang Z, Setny P, Dzubiella J, Li B, McCammon JA. Interfaces and hydrophobic interactions in receptor-ligand systems: A level-set variational implicit solvent approach. J Chem Phys. 2009;131:144102. doi: 10.1063/1.3242274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng LT, Xie Y, Dzubiella J, McCammon JA, Che J, Li B. Coupling the level-set method with molecular mechanics for variational implicit solvation of nonpolar molecules. J Chem Theory Comput. 2009;5:257–266. doi: 10.1021/ct800297d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis ME, McCammon JA. Electrostatics in biomolecular structure and dynamics. Chem Rev. 1990;90:509–521. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du Q, Liu C, Ryham R, Wang X. A phase field formulation of the Willmore problem. Nonlinearity. 2005;18:1249–1267. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du Q, Liu C, Wang X. A phase field approach in the numerical study of the elastic bending energy for vesicle memberanes. J Comput Phys. 2004;198:450–468. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dzubiella J, Swanson JMJ, McCammon JA. Coupling hydrophobicity, dispersion, and electrostatics in continuum solvent models. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:087802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.087802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dzubiella J, Swanson JMJ, McCammon JA. Coupling nonpolar and polar solvation free energies in implicit solvent models. J Chem Phys. 2006;124:084905. doi: 10.1063/1.2171192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emmerich H. The Diffuse Interface Approach in Materials Science: Thermodynamic Concepts and Applications of Phase-Field Models. Springer; Berlin and Heidelberg: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans LC, Gariepy RF. Measure Theory and Fine Properties of Functions. CRC Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feig M, Brooks CL., III Recent advances in the development and applications of implicit solvent models in biomolecule simulations. Curr Opinion Struct Biology. 2004;14:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleming WH, Rishel R. An integral formula for total gradient variation. Arch Math. 1960;11:218–222. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fogolari F, Brigo A, Molinari H. The Poisson–Boltzmann equation for biomolecular electrostatics: a tool for structural biology. J Mol Recognit. 2002;15:377–392. doi: 10.1002/jmr.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilmer GH, Gilmore W, Huang J, Webb WW. Diffuse interface in a critical fluid mixture. Phys Rev Lett. 1965;14:491–494. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giusti E. Minimal Surfaces and Functions of Bounded Variation. Birkhauser; Boston: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grochowski P, Trylska J. Continuum molecular electrostatics, salt effects and counterion binding—A review of the Poisson–Boltzmann model and its modifications. Biopolymers. 2008;89:93–113. doi: 10.1002/bip.20877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karma A, Kessler D, Levine H. Phase-field model of mode III dynamic fracture. Phys Rev Lett. 2001;87:045501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.045501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karma A, Rappel WJ. Phase-field model of dendritic sidebranching with thermal noise. Phys Rev E. 1999;60:3614–3625. doi: 10.1103/physreve.60.3614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohn RV, Sternberg P. Local minimisers and singular perturbations. Proc R Soc Edinb A. 1989;111:69–84. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koshi T, Yasuoka K, Ebisuzaki T, Yoo S, Zeng XC. Large-scale molecular-dynamics simulation of nanoscale hydrophobic interaction and nanobubble formation. J Chem Phys. 2005;123:204707. doi: 10.1063/1.2102906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koshi T, Yoo S, Yasuoka K, Zeng XC, Narumi T, Susukita R, Kawai A, Furusawa H, Suenaga A, Okimoto N, Futatsugi N, Ebisuzaki T. Nanoscale hydrophobic interaction and nanobubble nucleation. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93:185701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.185701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langer JS. Models of pattern formation in first-order phase transitions. In: Grinstein G, Mazenko G, editors. Directions in Condensed Matter Physics. World Scientic; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li B. Minimization of electrostatic free energy and the Poisson–Boltzmann equation for molecular solvation with implicit solvent. SIAM J Math Anal. 2009;40:2536–2566. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li B, Cheng X-L, Zhang Z-F. Dielectric boundary force in molecular solvation with the Poisson–Boltzmann free energy: A shape derivative approach. SIAM J Applied Math. 2011;71:2093–2111. doi: 10.1137/110826436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Morrone JA, Berne BJ. Are hydrodynamic interactions important in the kinetics of hydrophobic collapse? J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:11537–11544. doi: 10.1021/jp307466r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Modica L. The gradient theory of phase transitions and the minimal interface criterion. Arch Rational Mech Anal. 1987;98:123–142. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owen NC, Rubinstein J, Sternberg P. Minimizers and gradient flows for singularly perturbed bi-stable potentials with a Dirichlet condition. Proc R Soc Lond A. 1990;429:505–532. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Röger M, Schätzle R. On a modified conjecture of De Giorgi. Math Z. 2006;254:675–714. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roux B, Simonson T. Implicit solvent models. Biophys Chem. 1999;78:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(98)00226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Setny P, Wang Z, Cheng LT, Li B, McCammon JA, Dzubiella J. Dewetting-controlled binding of ligands to hydrophobic pockets. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;103:187801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.187801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shao D, Rappel WJ, Levine H. Computational model for cell morphodynamics. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;105:108104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.108104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharp KA, Honig B. Electrostatic interactions in macromolecules: Theory and applications. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1990;19:301–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.19.060190.001505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sternberg P. The effect of a singular perturbation on nonconvex variational problems. Arch Rational Mech Anal. 1988;101:209–260. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X. Asymptotic analysis of phase field formulations of bending elasticity models. SIAM J Math Anal. 2008;39:1367–1401. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z, Che J, Cheng LT, Dzubiella J, Li B, McCammon JA. Level-set variational implicit solvation with the Coulomb-field approximation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8:386–397. doi: 10.1021/ct200647j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ziemer WP. Weakly Differentiable Functions: Sobolev Spaces and Functions of Bounded Variation. Springer; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]