Abstract

Background: Within the Bologna reform, a longitudinal curriculum of “social and communicative competencies” (SOKO) was implemented into the new Bachelor-Master structure of undergraduate medical education in Basel (Switzerland).

Project description: The aim of the SOKO curriculum is to enable students to use techniques of patient-centred communication to elicit and provide information to patients in order to involve them as informed partners in decision making processes. The SOKO curriculum consists of 57 lessons for the individual student from the first bachelor year to the first master year. Teaching encompasses lectures and small group learning. Didactic methods include role play, video feedback, and consultations with simulated and real patients. Summative assessment takes place in objective structured clinical examinations (OSCE).

Conclusion: In Basel, a longitudinal SOKO curriculum based on students’ cumulative learning was successfully implemented. Goals and contents were coordinated with the remaining curriculum and are regularly assessed in OSCEs. At present, most of the workload rests on the shoulders of the department of psychosomatic medicine at the university hospital. For the curriculum to be successful in the long-term, sustainable structures need to be instituted at the medical faculty and the university hospital to guarantee high quality teaching and assessment.

Keywords: Communication skills, longitudinal curriculum, undergraduate medical education, Bologna process

Abstract

Hintergrund: Mit der Umstellung auf die Bachelor-/Masterstruktur wurde in Basel (Schweiz) ein longitudinales Curriculum „soziale und Kommunikative Kompetenzen“ (SOKO) in das Medizinstudium implementiert.

Projektbeschreibung: Ziel ist es, den Studierenden grundlegende Techniken einer patientenzentrierten Kommunikation in dem Sinne zu vermitteln, dass die Studierenden in der Lage sind, Informationen zu erheben und Informationen an Patientinnen und Patienten weiterzugeben, um sie als gut informierte Partner am Entscheidungsprozess zu beteiligen. Das SOKO Curriculum umfasst aus Sicht der Studierenden 57 Unterrichtsstunden. In Vorlesungen und kleinen Gruppen kommen vom 1. bis 3. Bachelor- und im 1. Masterstudienjahr Rollenspiele, Videofeedback, Simulationspatienten und der Kontakt mit realen Patienten als didaktische Methoden zum Einsatz. Die Lernziele werden in den summativen klinisch-praktischen OSCE-Prüfungen abgeprüft.

Schlussfolgerungen: In Basel konnte mit der Umstellung auf die Bologna-Struktur ein longitudinales SOKO-Curriculum implementiert werden, das kumulatives Lernen erlaubt, auf die Inhalte des sonstigen Studiums Bezug nimmt und regelmäßig in den OSCEs abgeprüft wird. Zurzeit wird ein Großteil der Lehre durch die Psychosomatik des Unispital Basels geleistet. Für die Zukunft wird entscheidend sein, nachhaltige Strukturen in der gesamten Fakultät und im gesamten Unispital zu verankern, um dauerhaft eine hohe Qualität des Unterrichts und der Prüfungen sicherzustellen.

Background

Bologna process in Switzerland

Switzerland was one of the first countries to consequently implement the regulations of the Bologna process for all degree programmes of higher education including medical education [1], [2]. The process led to a conversion from the traditional six- year single-cycle curriculum to a two-cycle structure with a three-year Bachelor and a three-year Master programme. The medical faculties seized this opportunity to evaluate the existing curriculum and implement innovative teaching and assessment formats into the new programme. Relatively new disciplines and medical competencies like communication skills, humanities, palliative medicine, medical ethics, and family medicine were reconsidered and integrated into the curriculum structure. Parts of this implementation process had already started before the Bologna reform. It was therefore possible to rely on previously established concepts and experience [1], [3], [4].

Published in 2002, before the implementation of the Bologna process, the Swiss Catalogue of Learning Objectives (SCLO) provided a definition of the educational objectives for undergraduate medical education that was accepted by all medical faculties in Switzerland. The SCLO defined the competencies of a graduate after completing 6 years of medical education, and since implementation of the Bologna process, awards graduates with the degree “Master of Medicine”. A revised version of the SCLO was published 2008 [5]. It is now the basis for the Swiss federal licensing examination comprising a written and a clinical examination [6].

Bologna-compatible medical education in Basel

The Bachelor and Master programme in Basel consists of both a core curriculum and special study modules. In the Bachelor programme, the core curriculum includes organ-based modules and a longitudinal curriculum called “basic competencies” (BC) which covers four areas:

practical skills, diagnostic and therapeutic procedures,

social and communicative competencies (SOKO),

scientific competencies, and

Humanities and medical ethics.

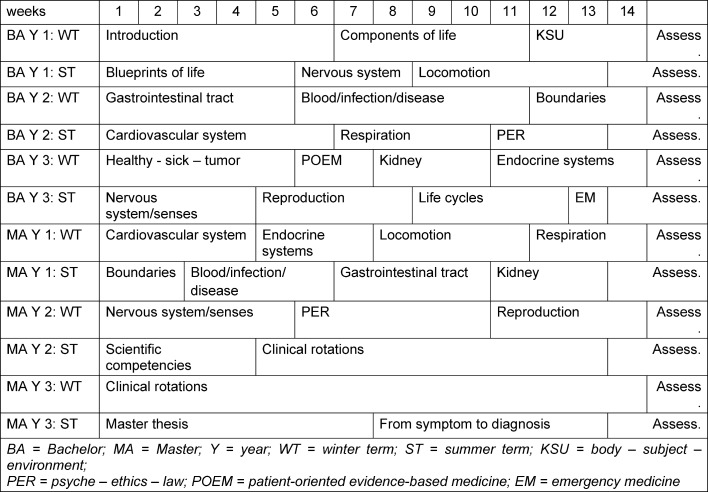

The structure of the Master programme is comparable to the Bachelor programme but the longitudinal curriculum is now called “advanced competencies” (AC). In addition to the organ-based modules, students have to complete ten months of clinical rotations, and a master thesis. An overview of the organ-based modules is given in figure 1 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Organ-based modules of the Basel undergraduate medical programme.

The learning outcomes of the organ-based modules are assessed with end-of-semester examinations using a multiple choices format. The learning outcomes of the longitudinal curriculum (BC and AC) are assessed at the end of each year with an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). For logistical reasons, in some years the OSCE is split in partial examinations after each semester. The results of the partial examinations are then summed up to a yearly result. Results from single OSCE stations can be compensated with results from other stations, i.e. the OSCE as a whole must be passed, not single stations. Both the multiple choice examination and the OSCE must be passed to acquire the required credit points and to proceed to the next year of studies. Compensation between the written examination and the OSCE is not possible.

In addition to the core curriculum, students have to take special study modules where they can focus on individual interests. During the Bachelor programme, they can choose different topics from a set of options. During the Master programme, students are attached to family medicine, pharmacotherapy, and public health. Participation is obligatory. Assessment is integrated into the modules.

Communicative and social competencies in medical education

Consensus statements and recent publications call for integrating communication skills training into the clinical context [7], [8], [9], [10]. Van Dalen and colleagues demonstrated in a comparative study, that an integrated longitudinal curriculum resulted in more effective learning of communication skills than a concentrated course in the preclinical years [11]. Against this background, a longitudinal communication (SOKO) curriculum from the first Bachelor year to the first Master year was established in Basel. The aim is to prepare students for patient contact and accompany them during the course of their studies. The primary objective of the SOKO curriculum is to shape communication in such a way that patients are given an audible voice. Thereby, a student can experience each patient as an individual with a unique history and every patient can leave a distinct and lasting impression on the student. Appropriate communication skills are used to open the space for the patient in terms of patient-centred communication. With this approach, each patient contact has the potential of being a valuable learning opportunity in which students can experience how the patient’s personal history is connected to his or her health, illness, and coping with suffering.

Description of the SOKO curriculum

Underlying models and concepts of effective communication

The aim of the Basel SOKO curriculum is to train students to gather correct and complete data (e.g. history taking) and to share information with patients in order to enable them to act as well-informed partners in the decision making processes [12], [13]. A limited number of communication techniques are trained that are then applied in different combinations to cope with different complex tasks such as breaking bad news or shared decision making. In principle, the techniques can be divided into two categories: “opening space” and “limiting space”. The task is, therefore, not necessarily to give patients room for an infinite narrative [14] but to provide students with techniques to manage encounters with different focal points.

A typical field of application of opening and limiting space is classical history taking. Primarily, it is about gathering information from the patient [13]. To accomplish this, there are two sets of communication techniques, those that can be used to test hypotheses and those that can be used to generate hypotheses. Testing a hypothesis in the process of history taking makes sense when the doctor already has distinct assumptions about the patient’s problem and these can be verified or falsified [15]. A typical example would be a 65-year old patient in the emergency room with acute left-sided thoracic pain and dyspnoea. Due to the constellation of symptoms and the patient’s age, it is highly likely that the suspected diagnosis “angina pectoris” can be verified or falsified with few additional data. It would be adequate to ask very directed and specific closed questions (“Did the pain appear during physical effort?”, “Have you experienced these symptoms before?”, “Do you smoke?” etc.). Such questions are frequently used by clinical experts in university hospitals with a highly selected patient mix and therefore observed frequently by students. Experts construct illness scripts and compare patients’ symptoms with their illness scripts. With growing expertise, testing hypotheses and subsequent data gathering become more and more precise and direct [16].

Communication techniques to generate hypotheses make sense when a constellation of symptoms do not lead to a specific diagnosis. An example would be a patient who visits the general practitioner due to increasing fatigue over the past weeks. In this situation, the doctor would invite the patient to tell his story. The doctor would use communication techniques that are abbreviated in the acronym WEMS (“Waiting, Echoing, Mirroring, Summarising”) to open the narrative space for the patient. Comparable techniques are called “reflecting back” and are used in the field of motivational interviewing when it is important to learn more about the patient’s individual reasons in order to enable or change a specific behaviour [17], [18].

Communication techniques that limit space also help students to structure an encounter, e.g. in relation to time, topic, and language flow. Students learn to verbalise their own function and task, to ask the patient for specific expectations and to match these expectations with their own tasks and the given time schedule for the encounter. Students are encouraged to redirect patients to the topics that were negotiated at the beginning of the interview (“I notice that you do have urging questions about the financial aspects of your new wheel chair. We cannot talk about that at this moment but I would like to come back to this issue tomorrow when we see each other during the ward round.”).

Sharing complex information requires very explicit structuring during the interview. For this task the so-called “book metaphor” can be applied effectively. The book metaphor transfers the structure of a book to the interview: title, table of contents, title of chapters, and text. Meta-communication techniques are used to help patients to re-orientate themselves during the encounter: providing overviews (“at the moment, we are talking about …”), signposting (“now, we will come to the next issue…”), summarising (“I would like to summarise what we have talked about already….”). Pieces of information are presented in small coherent portions (“chunking”) after which a pause follows to check the understanding of the patient. Only if the patient verbally or non-verbally signalises that he or she is able to follow and continue does the student provide the next portion of information.

If the student is able to open and limit space, another educational objective, namely dealing with emotions, will be trained. Students are often, but often unspectacularly, confronted with patients’ emotions, concerns, and fears, and students have to react to these. In Basel, students are trained in specific skills to handle emotions and concerns that are abbreviated in the acronym NURSE, which means naming emotion, understanding emotion, respecting = showing respect for the patient, supporting, exploring emotion [19], [20].

Another important task of clinical work is making decisions together with the patient about diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and treatment plans, especially if there are several equally effective options. Depending on the patient’s preference, decisions can be made either by the doctor, or by the patient, or in a shared manner [21], [22], [23]. The first step in communication with the patient would be for the doctor to identify the patient’s preference and to provide the relevant complex information in a manner which helps the patient take part in the decision making process. The information needs to be adapted to the patient’s health and disease concept which cannot be identified by directed questions but by listening to patient’s narrative [24]. The above mentioned communication techniques are also used for breaking bad news. This task can be defined as a combination of providing or sharing complex information and dealing with emotions [20].

Design of the SOKO curriculum

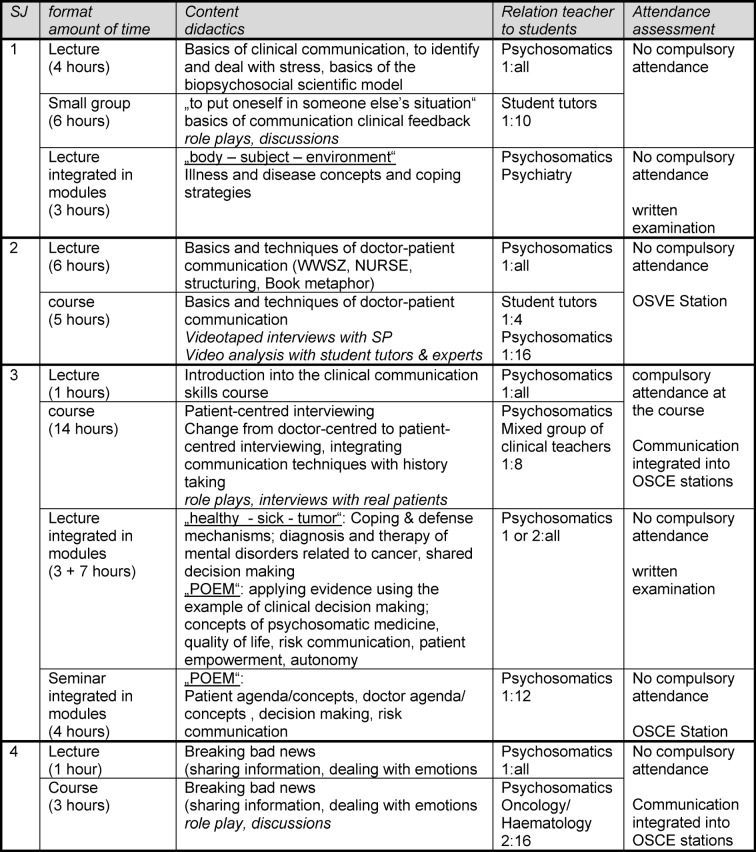

The longitudinal SOKO curriculum combines lectures, seminars, and small group learning from the first Bachelor to the first Master year (see table 1 (Tab. 1)). The course contents refer to requirements and course contents of other parts of the medical curriculum.

Table 1. Longitudinal SOKO curriculum „social and communicative competencies“.

Bachelor year 1

In the first year of studies, students are introduced into the basics of clinical communication and into the biopsychosocial model as a complement to the biomedical model. Students meet clinical role models and use communication skills to interview the clinicians about their attitude towards their profession. The clinicians share their knowledge and experience either by answering the students’ direct questions or in the form of narratives. Students also attend exercises about dealing with stress and how to provide and receive feedback. The latter is intended to support students’ teamwork in their problem-based tutorials. It trains students to observe the behaviour of others and helps them to distinguish between describing and interpreting observable phenomena (“I noticed that your feet were tapping during the whole interview” versus “you look nervous”). The exercises are conducted by peer tutors who accompany and support the students for the entire first year during the special study modules. The peer tutors therefore slip into the role of mentors for the first-year students.

Bachelor year 2

The second year of studies is dedicated to the training of the above mentioned communication techniques. In small groups of four, students meet four simulated patients (SP), one after another. Each student has to interview a SP and functions as an observer for the other three student-SP encounters. After the interviews, students identify communication techniques as well as communication challenges and provide feedback for each other. The interviews are videotaped and given to a peer tutor after the first session. The peer tutor watches the videos and identifies so-called teachable moments, which are sequences that are interesting from the point of view of communication. These teachable moments are discussed with the students in a second session together with the peer tutor. In a third session, four groups of four students (i.e. 16 students) meet an expert who is a clinician and a communication expert. The students and the expert discuss unclear or complex or particularly interesting teachable moments. Students again receive individual feedback and have the opportunity to try out alternative behaviour in role play.

Bachelor year 3

In the third year of studies, students attend a communication skills course for medical interviewing skills as well as lectures and seminars dealing with sharing information, risk communication, and decision making. After a theoretical introduction, students train their interviewing skills in the communication skills course first with role play and later with real patients. The above mentioned techniques (WEMS, NURSE, book metaphor) are trained as are the integration of communication skills and history taking. Each group of students is supervised by a clinical teacher from different disciplines, at present from family medicine, gynaecology, paediatrics, psychotherapy, psychosomatics, and internal medicine. The teachers work either at the university hospital or in their own practice. All of them have attended a train-the-trainer course.

Lectures and seminars related to communication are embedded in the organ-based modules “healthy – sick – tumor” and “patient-oriented and evidence-based medicine”. A theoretical introduction is given on coping and defensive mechanisms of patients with cancer, shared decision making, risk communication, patient empowerment, and patient autonomy. In seminars, students discuss discrepancies between the patient and the doctor agenda and practice means to come to shared approaches, and to discuss risks and benefits of treatment options with patients as well as modes of shared-decision making. Students can apply their communication skills during the bedside teaching in internal medicine and surgery that also takes place in the third Bachelor year.

Master year 1

Communication skills lectures and seminars in the first master year are dedicated to breaking bad news. In groups of twelve, students meet a haematologist or oncologist and a psychosomatic expert to discuss and train breaking bad news. Active training is conducted in role play. During the first Master year, students have several opportunities to train and consolidate their communication skills. Again, students attend bedside teaching in internal medicine and surgery. They also participate in one-to-one tutorials at a family medicine practice on a weekly basis for 20 afternoons over the course of the academic year. During the one-to-one tutorial the students have regular and continuous patient contact and receive valuable feedback from the general practitioner on their manner of interacting with patients [24].

In the context of their longitudinal humanities curriculum, students are asked to reflect on patient interactions. They are required to write a reflective writing essay on a patient encounter within the context of the one-to-one tutorial, e.g. “A patient encounter where you had the impression that you could not build up a relationship properly” [24].

Assessment of communication skills

Communication skills are assessed at the summative end-of-year OSCEs together with other clinical skills. Depending on the year of study, an OSCE consists of six to twelve stations including stations using a computer (Objective structured video examination, OSVE). During the first study years, communications skills are assessed with OSVE stations. Stimuli are short videos. Students have to respond to specific lead-in questions in a constructed response format. For example, students have to write down in direct speech how they would give feedback to a student just seen in the video or they have to identify and analyse communication techniques in different doctor-patient encounters.

From the third Bachelor year on, students’ communication skills are assessed in OSCE stations where they are confronted with a standardised patient. Checklists include content-related items (e.g. specific aspects of history taking) and process-related items measuring communication skills. Content-related items vary from station to station. Process-related items are kept stable for all of the different stations that are used from the third Bachelor year to the second Master year. This means, that all assessors across all clinical disciplines also have to assess communication skills and accordingly are trained in communication skills before each OSCE. The positive side effect of this approach is that clinicians who are not involved in communication skills trainings are forced to deal with the communication techniques that are trained in the Basel SOKO curriculum.

Since 2011, communication skills are also assessed at the clinical skills assessment of the Swiss federal licensing examination. Like in Basel, an integrated assessment approach is used. In all stations, case-specific content-related aspects and process-related items measuring communication skills are assessed concurrently [6].

Teaching effort and teaching hours per student

Teaching effort for all teachers of the SOKO curriculum consists of approximately 400 hours. Student numbers are about 180 students in the first and second year of studies and about 140 students in the third year of the Bachelor programme and the first year of the Master programme. Approximately 300 hours are additionally required for student tutors. In addition to the teaching hours, the designing, conducting and scoring of assessments, in particular for the OSCE/OSVE stations necessitate an additional 150 hours. Organisation of teaching and assessment entails another 100 hours. All in all, the effort for running the SOKO curriculum can be estimated to require 950 hours per year. The financial budget includes the fees for student tutors and simulated patients, producing videos and other material that is needed for teaching and assessment. Video cameras are provided by the learning centre of the medical faculty in Basel.

From the student perspective, the SOKO curriculum consists of 57 teaching hours including lectures and seminars that are integrated in organ-based modules and deal with communication and related issues. All in all, students attend 22 hours of lectures and 35 hours of seminars and small groups. Assuming that an undergraduate medical programme in Europe includes 5.500 hours [25] which holds true for Basel, then the SOKO curriculum represents approximately one percent of the whole medical programme.

Evaluation

The modules and courses of the medical curriculum in Basel are evaluated on a cyclic basis [26]. The SOKO curriculum has not been evaluated in the last years or since implementation of the Bologna-process. However, individual communication skills courses in the second and third Bachelor year have been evaluated by the course organisers themselves.

Evaluation of the communication skills course in Bachelor year 2

The communication skills course was evaluated by the students in May/June 2010. Of the 151 students that were enrolled into the course, 102 filled out a questionnaire, which represents a 68% response rate. Among the students who returned a questionnaire, 87% were satisfied with the communication skills course. Video recording and small group discussion were considered helpful to improve their own communication skills by 90% of the students. The session with the expert supervisor was also evaluated very positively. More than 90% of the students deemed that they could identify communication skills more effectively after the course. 87% of the students confirmed that the discussion with the expert supervisor helped them to improve their own communication skills. Identifying communication skills more effectively was considered the most positive aspect with the expert supervisor.

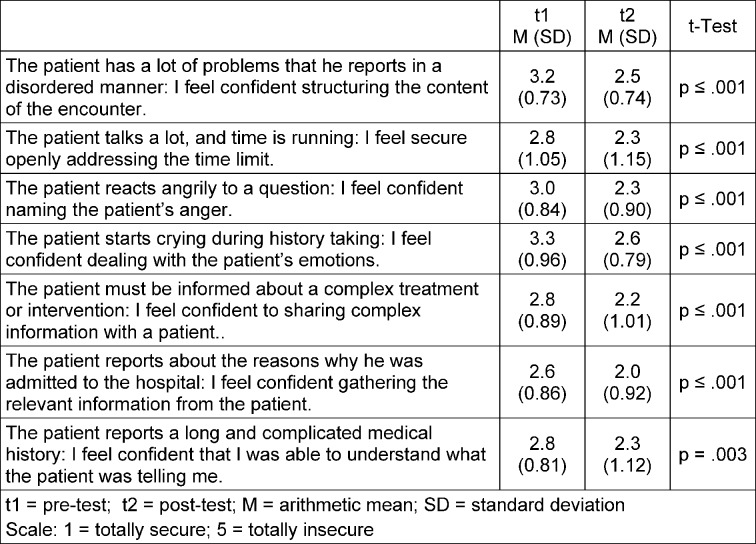

Evaluation of the communication skills course in Bachelor year 3

In the winter term 2009/2010, the communication skills course in the third year of studies was evaluated with a pre-post-design. Students were asked to judge how secure they were in managing specific medical encounters. Items of the questionnaire were related to communication techniques which were trained during the course (structuring an interview, dealing with emotions, gathering and sharing information). It was possible to match pre-post data for 75 students, which represents approximately 55% of the student class. The level of significance was adjusted according to Bonferroni to minimise the alpha error (p=.007). Students felt more confident in all seven aspects after the course (see table 2 (Tab. 2)). Due to data protection, it was not possible to correlate the data with OSCE results. Students were also able to comment on the course. They were asked to name personal goals for the communication skills course. Most frequent goals were to conduct an interview with a patient (e.g. history taking) applying specific communication skills, to become more confident in dealing with patients and in particular with patients’ emotions. These goals are thus consistent with the educational objectives of the communication skills course.

Table 2. Evaluation of the communication skills course in the Bachelor year 3: pre-post testing about self-perceived secureness in dealing with specific encounters.

Discussion

Over the last few years, different educational activities related to communicative and social competencies were integrated into four consecutive years of the medical programme in Basel. Thereby, a longitudinal curriculum was implemented that allows cumulative learning. Course contents build on each other, are related to other competencies and contents of the medical programme, and are assessed continuously with OSCEs [9]. Special emphasis was placed on a limited number of specific communication techniques which are trained in simulated and real situations time and time again with a growing level of difficulty. The selection of the communication techniques is based on two criteria. Within the overall objective of patient-centred communication, the techniques aim to give the patient room and a voice in the conversation. In addition, they aim at helping students gather complete and correct data and share information with the patients. This enables patients to become well-informed partners in the decision-making process. The second criterion is related to the scientific foundation and validation of communication techniques with empirical studies. For some of the communication techniques, effectiveness has been shown [19], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. For other techniques, no evidence has been provided yet. It is the explicit aim for the next years to conduct research studies to evaluate the effectiveness of these communication techniques.

To decide which contents and conversational challenges a longitudinal curriculum should address, it is important to consider what kind of competencies and encounters students can train during their undergraduate medical studies. Some communication challenges may occur for the first time during postgraduate training. Others may only be important for some clinical disciplines so that students might focus on them during their special study modules. A number of consensus statements and catalogues of learning objectives give details and recommendations to answer this question [10], [32], [33], [34], [35]. If we compare the objectives and contents of the Basel SOKO curriculum with the SCLO and the Basel Consensus statement [33] - a position paper of the German Association for Medical Education - it becomes obvious, that some of the recommended objectives are not or rarely trained within the SOKO curriculum: social accountability, communication of errors, team work, leadership, self-management and self-organization, integration into professional contexts (socialization), written communication, and one’s own role and identity. Balint groups are a very suitable method to reflect on one’s identity as a medical doctor. Balint groups have been offered to students in the third Bachelor year and in the first and second Master year on a voluntary basis. However, students showed little interest and scarcely used the voluntary offer.

The selection of course content and the amount of hours a longitudinal communication skills curriculum should include are related. In Basel, approximately one per cent of the total amount of teaching hours during the undergraduate programme seems to be quite low. However, at the moment, there are no recommendations or data on how many teaching hours a communication skills curriculum should include. Dedicating time to a specific element of medical education will also always be a political question that has to be negotiated in teaching committees or similar bodies. New competencies, contents or disciplines will always struggle to receive time in an existing educational programme. Even if they are integrated additively with extra hours, logistical issues (e.g. organising rooms, time scheduling) may well limit the design and delivery of a course. The amount of teaching time for a course therefore results from a combination of content-related considerations and the impact of the negotiation skills of the course leader and his or her fellow campaigners.

Considerations for the future

Who are the significantly involved supporters and fellow campaigners of the SOKO curriculum in Basel? The major effort of teaching, assessing, and organising the educational activities is borne by the psychosomatic staff which is part of the department of internal medicine. Other engaged clinicians come from very different clinical disciplines including general practitioners and specialised physicians in their own practice, as well as psychotherapists. It remains to be seen, whether this organisational structure is sufficient to sustainably maintain the high quality of the SOKO curriculum. At the moment, quality is very much dependent on the commitment of individuals, who score OSVE stations, offer Balint groups, and train teachers in their spare time. The future challenge will be to establish and anchor sustainable structures in the faculty and in the university hospital to provide a longitudinal communication skills curriculum not only by a small group of enthusiasts but by the majority of clinical teachers.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. Daniel Bauer, researcher at the chair of Medical education at the university hospital in Munich for critically reviewing the manuscript and Claudia Steiner, MA, Psychosomatic Medicine Basel, for her great help in translating the manuscript into English.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Michaud PA. Reforms of the pre-graduate curriculum for medical students: the Bologna process and beyond. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13738. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rektorenkonferenz der Schweizer Universitäten (CRUS) Hochschulmedizin 2008. Bern: CRUS; 2004. Available from: http://www.crus.ch/dms.php?id=826. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaiser HJ, Kiessling C. Two-cycle curriculum - bachelor-master structure according to the Bologna agreement: the Swiss experience in Basle. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2010;27(2):Doc31. doi: 10.3205/zma000668. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kündig P. Bologna in Medicine: the situation in Switzerland. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2010;27(2):Doc18. doi: 10.3205/zma000655. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgi H, Rindlisbacher B, BaderC, Bloch R, Bosman F, Gasser C, GerkeW, Humair JP, Im Hof V, Kaiser H, Lefebvre D, Schläppi P, Sottas B, Spinas GA, Stuck AE. Swiss Catalogue of Learning Objectives for Undergraduate Medical Training. 2nd. Bern: Universität Bern; 2008. Available from: http://sclo.smifk.ch. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bundesamt für Gesundheit (BAG) Eidgenössische Prüfung Humanmedizin. Bern: Bundesamt für Gesundheit (BAG); 2012. Available from: http://www.bag.admin.ch/themen/berufe/07918/07919/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Report III. Contemporary Issues in Medicine: Communication in Medicine. Medical School Objectives Project. Washington: Association of American Medical Colleges; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makoul G, Schofield T. Communication teaching and assessment in medical education: an international consensus statement. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;137(2):191–195. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00023-3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman J. Teaching clinical communication: A mainstream activity or just a minority sport? Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(3):361–367. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.011. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachmann C, Hölzer H, Dieterich A, Fabry G, Langewitz W, Lauber H, Ortwein H, Pruskil S, Schubert S, Sennekamp M, Simmenroth-Nayda A, Silbernagel W, Scheffer S, Kiessling C. Longitudinales, bologna-kompatibles Modell-Curriculum "Kommunikative und soziale Kompetenzen": Ergebnisse eines interdisziplinären Workshops deutschsprachiger medizinischer Fakultäten. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2009;26(4):Doc38. doi: 10.3205/zma000631. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Dalen J, Kerkhof E, Van Knippenberg BW, Van den Houts HA, Scherpbier AJ, Van Vleuten CP. Longitudinal and Concentrated Communication Skills Programmes: Two Dutch Medical Schools Compared. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2002;7(1):29–40. doi: 10.1023/A:1014576900127. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1014576900127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langewitz WA. Patientenzentrierte Kommunikation. Theoretische Modelle und klinische Praxis. In: Adler RH, Herzog W, Joraschky P, Köhle K, Langewitz W, Söllner W, Wesiack W, editors. Uexküll. Psychosomatische Medizin. Theoretische Modelle und klinische Praxis. München: Urban & Fischer; 211. pp. 338–347. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langewitz WA. Zur Erlernbarkeit der Arzt-Patienten-Kommunikation in der Medizinischen Ausbildung. Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2012;55:1176–1182. doi: 10.1007/s00103-012-1533-0. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00103-012-1533-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumagai AK. A Conceptual Framework for the Use of Illness Narratives in Medical Education. Acad Med. 2008;83(7):653–658. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181782e17. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181782e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klahr D, Dunbar K. Dual Space Search during scientifitc Reasoning. Cogn Scie. 1988;12:1–48. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog1201_1. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1201_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Internal Med. 2005;165(13):1493–1499. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1493. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.13.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rollnick S, Butler CC, Kinnersley P, Gregory J, Mash B. Motivational interviewing. BMJ. 2010;340:c1900. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller WR, Moyers TB, Ernst D, Amrhein P. Manual for the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC) Albuquerque: The University of New Mexico: Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions; 2008. Available from: http://casaa.unm.edu/download/misc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith RC. Patient-Centered Interviewing: An Evidence-Based Method. 2nd. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Williams; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Fryer-Edwards KA, Alexander SC, Barley GE, Gooley TA, Tulsky JA. Efficacy of Communication Skills Training for Giving Bad News and Discussing Transitions to Palliative Care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):453–460. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitney SN, McGuire AL, McCullough LB. A typology of shared decision making, informed consent, and simple consent. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(1):54–59. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-1-200401060-00012. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-140-1-200401060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kriston L, Scholl I, Hölzel L, Simon D, Loh A, Härter M. The 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9). Development and psychometric properties in a primary care sample. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(1):94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.034. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Légaré F, Ratté S, Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Gravel K, Graham ID, Turcotte S. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;12(5):CD006732. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiss A, Steiner C. Is student satisfaction with the feedback to their reflective writing assignments greater when the tutors are instructed? A controlled randomized study. Basel: Universität Basel; 2010. Available from: http://illness-narratives.unibas.ch/?The_Individual_Project_Parts:Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The European Parliament and of the Council of the European Union. Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of the 7. September 2005 on the recognition of professional qualifications. Brüssel: The European Parliament; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medizinische Fakultät der Universität Basel. Konzept der Lehr-Evaluation an der Medizinischen Fakultät zu Basel. Basel: Universität Basel; 2009. Available from: http://medizinstudium.unibas.ch/allgemeine-infos/evaluation-der-lehre.html. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152(9):1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith S, Mitchell C, Bowler S. Standard versus patient-centred asthma education in the emergency department: a randomised study. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(5):990–997. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00053107. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00053107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langewitz WA, Edlhaimb HP, Höfner C, Koschier A, Nübling M, Leitner A. Evaluation eines zweijährigen Curriculums in Psychosozialer und Psychosomatischer Medizin – Umgang mit Emotionen und patientenzentrierter Gesprächsführung. Psychother Psych Med. 2010;60(11):451–456. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1251980. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1251980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Childers JW, Bost JE, Kraemer KL, Cluss PA, Spagnoletti CL, Gonzaga AM, Arnold RM. Giving residents tools to talk about behavior change: A motivational interviewing curriculum description and evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(2):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.08.001. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quilligan S, Silverman J. The skill of summary in clinician–patient communication: A case study. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(3):354–359. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.009. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makoul G. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76(4):390–393. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200104000-00021. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200104000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiessling C, Dieterich A, Fabry G, Hölzer H, Langewitz W, Mühlinghaus I, Pruskil S, Scheffer S, Schubert S. Basler Consensus Statement "Kommunikative und soziale Kompetenzen im Medizinstudium": Ein Positionspapier des GMA-Ausschusses Kommunikative und soziale Kompetenzen. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2008;25(2):Doc83. Available from: http://www.egms.de/static/de/journals/zma/2008-25/zma000566.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Fragstein M, Silverman S, Cushing A, Quilligan S, Salisbury H, Wiskin C UK Council for Clinical Communication Skills Teaching in Undergraduate Medical Education. UK consensus statement on the content of communication curricula in undergraduate medical education. Med Educ. 2008;42(11):1100–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03137.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bachmann C, Abramovitch H, Barbu CG, Cavaco AM, Elorza RD, Haak R, Loureiro E, Ratajska A, Silverman J, Winterburns S, Rosenbaum M. A European consensus on learning objectives for a core communication curriculum in health care professions. Patient Educ Couns. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.016. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leventhal H, Diefenbach M, Leventhal EA. Illness Cognition: Using Common Sense to Understand Treatment Adherence and Affect Cognition Interactions. Cogn Ther Res. 1992;16(2):143–163. doi: 10.1007/BF01173486. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01173486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]