Sir,

Sialolithiasis is considered to be the most common salivary gland disorder and it accounts for about 1.2% of unilateral major salivary gland swelling. Submandibular gland has got highest predilection for sialolithiasis with 80% occurrence rate, followed-by 19% in the parotid and 1% in the sublingual glands.[1] Sialolithiasis usually appears between the age of 30 and 60 years, and it is uncommon in children as only 3% of all sialolithiasis cases has been reported in the pediatric population until to date. Males are affected twice as much as females.[2,3]

Six cases of sialolithiasis with varying presentations and clinical features reported to our Departments of Oral Medicine and Radiology and Oral and Maxillofacial surgery in PSM College of Dental Sciences and Research. A brief discussion based on the clinical examination, investigation, and management of sialolithiasis is being reported.

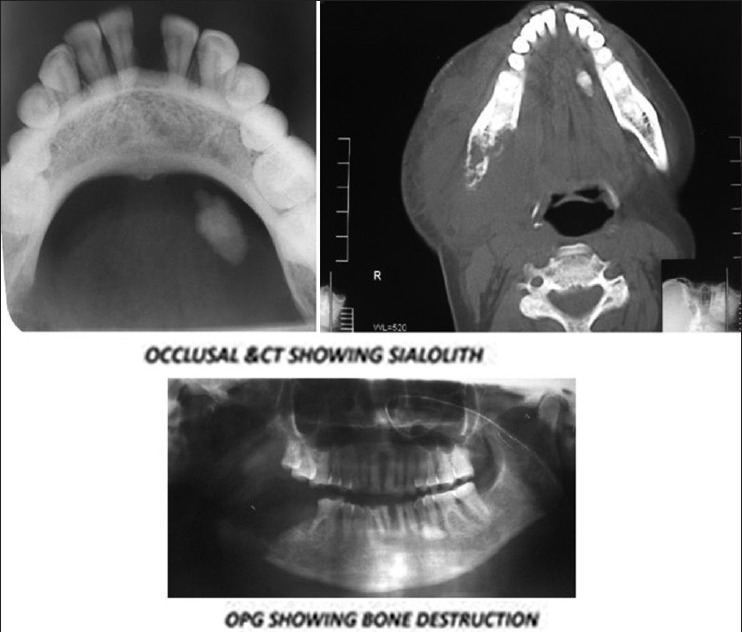

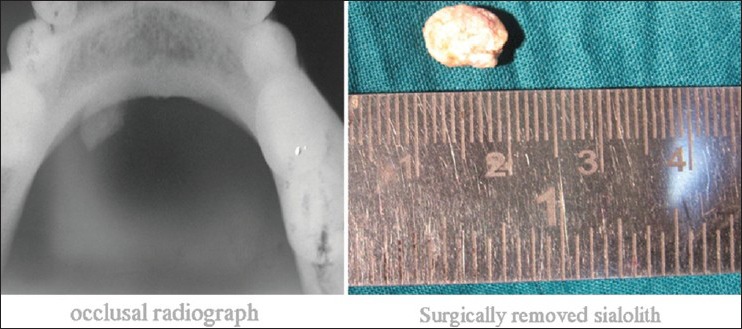

A 55-year-old female patient came with a complaint of pain in the right mandibular region for 3 months. Previous history revealed a swelling on the same side 7 years back, which was then diagnosed as osteomyelitis and no treatment was carried out. Clinical examination revealed a swelling in the floor of the mouth on the right side with complete destruction of alveolar bone. Orocutaneous fistula with the myiasis was evident. Occlusal, computed tomography (CT) and Ortopantomograph confirmed the presence of sialolith. A diagnosis of osteomyelitis and sialolithiasis was given on the basis of clinical and the radiological examination [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

First case

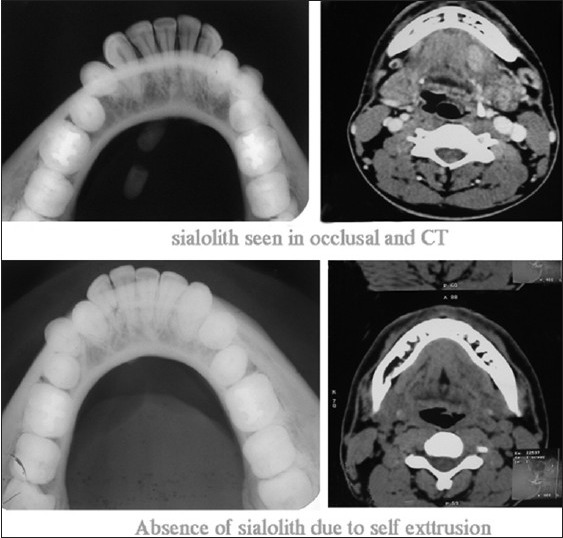

A 25-year-old male patient came with a complaint of pain in the lower left back tooth region for a period of 5 days. Pain was recurrent in nature. There was no history of any increase of the swelling during meals. Clinical examination revealed an impacted 38 associated with a firm, tender swelling on the left floor of the mouth. Occlusal radiographic examination revealed two tubular radiopacities in the left side. A CT was taken, which confirmed the presence of calculi. A diagnosis of sialolith was given. Patient was posted for the surgical removal. Prior to surgery a clinical examination revealed a reduction of signs and symptoms. Repeat radiographs and CT revealed the absence of radiopacities. This led to a conclusion of spontaneous extrusion of sialolith [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Second case

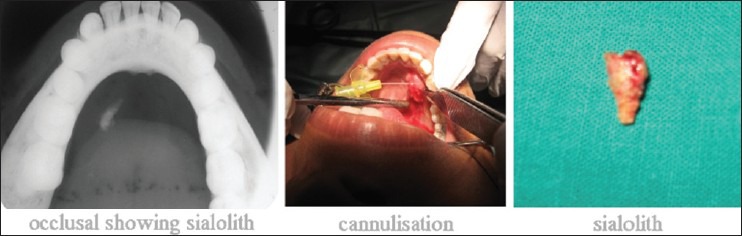

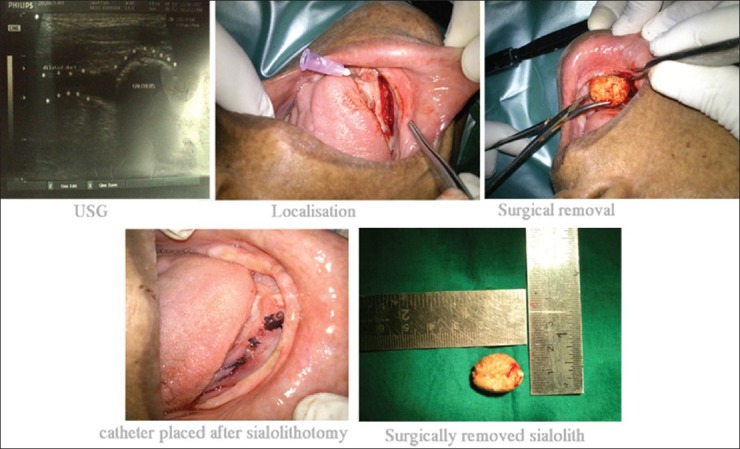

Three cases of female patients also reported with the complaints of swelling in the floor of the mouth with pus discharge. Occlusal radiographic examination revealed radiopacities, which led to diagnosis of sialedenitis associated with the salivary calculi in all the three cases. Surgery was planned. Under antibiotic coverage, Duct was isolated with an IV cannula, incision was placed longitudinally along the margins, and stone was identified. Calculi were removed in total and ductal walls were marsupilised. Healing was satisfactory in all the three cases [Figures 3-5].

Figure 3.

Third case

Figure 5.

Fifth case

Figure 4.

Fourth case

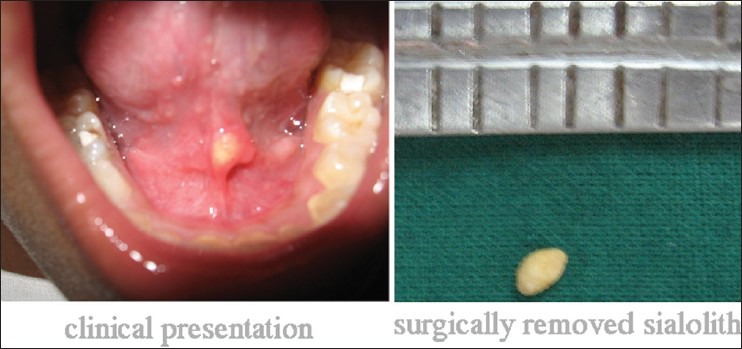

An 8-year-old female patient reported with a swelling below the tongue, which was associated with pain for 1 week. Clinical examination revealed a superficial, 5 mm hard swelling situated near the lingual frenum, which was extremely tender on palpation. There was no associated discharge or bleeding reported from the area. Under local anasthetic, incision was placed at the ductal orifice and calculi was exposed and retrieved [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Sixth case

Regarding the occurrence of sialolith, in our series, all the cases were reported in the submandibular gland, which was consistent with the fact that it commonly occurs in the submandibular gland. The cases reported here were unusual, because the data didn’t coincide with those reported in literature about the male predilection[4] and rarity of occurrence in pediatric patients.[5] A total of 90% of our patients were females, and one of our reported cases was of an 8-year-old child.

Acute sialadenitis of the submandibular gland is the most common form of inflammation to the major salivary glands. Obstruction of the salivary duct due to sialolithiasis is the most frequent etiology of sialadenitis. Hence patients with sialolithiasis can have acute pain due to sialadenitis[6] and this was consistent with most of our cases.

Sialolithiasis is easy to diagnose on the basis of its clinical features. Occlusal radiographs are extremely useful in showing radiopaque stones unless otherwise there are radiolucent stones. Sialography is useful in patients showing signs of sialadenitis related to the radiolucent stones or deep submandibular/parotid stones. Sialography is contraindicated in acute infection or patients who are having contrast allergy.[6] Ultrasonography with a 99% accuracy is considered as a gold standard in diagnosis. Newer techniques such as scintigraphy, CT, and sialoendoscopy has revolutionized the diagnostic aspect of sialolithiasis.[7]

On the basis of a review of the literature, most of the sialolith are usually of 5 mm in maximum diameter and all the stones over 10 mm should be reported as a sialolith of unusual size.[7] Some of our cases were more than 10 mm in size and can be considered as giant sialolith.

The management of sialolith is based on its location and the symptoms associated with it. Moist warm heat application with administration of sialogogues and gland massage helps in flushing the stone out of the duct.

Most stones will respond to antibiotics, combined with simple sialolithotomy. Under regional anesthesia, once the sialolith had been located, the orifice of the salivary duct has to be surgically enlarged with a long incision. A small pressure exerted at the level of the distal ligature will provoke the discharge of the sialolith through the incision. Risks of this procedure include infection and bleeding. More uniquely to this procedure is the risk of duct scarring resulting in recurrent gland swelling. There is also a small risk of numbness to the floor of mouth region. In cases of bigger stones, prior fragmentation is necessary using an external lithotriptor or laser can be used if necessary. Stenoses in the main duct are treated with metallic dilators although, balloon catheters under endoscopic control is preferred when strictures are localized or situated in peripheral areas.[8]

Our case reports discuss sialolith presented in different sites such as submandibular gland and lingual frenum; its occurrence in a pediatric patient, and self-extrusion of a sialolith. Diagnosis of salivary calculi is mainly based on clinical symptoms and imaging. Management is by surgical means and has to be performed only after managing any infection or inflammation. Even though, surgical treatment is the mainstay treatment modality at present, minimally invasive techniques like lithotripsy will gain attention in the future.

References

- 1.Batori M, Mariotta G, Chatelou H, Casella G, Casella MC. Diagnostic and surgical management of submandibular gland sialolithiasis: Report of a stone of unusual size. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2005;9:67–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siddiqui SJ. Sialolithiasis: An unusually large submandibular salivary stone. Br Dent J. 2002;193:89–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nahlieli O, Eliav E, Hasson O, Zagury A, Baruchin AM. Pediatric sialolithiasis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:709–12. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.109075a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodner L. Giant salivary gland calculi: Diagnostic imaging and surgical management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:320–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaban LB, Mulliken JB, Murray JE. Sialadenitis in childhood. Am J Surg. 1978;135:570–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchal F, Kurt AM, Dulguerov P, Lehmann W. Retrograde theory in sialolithiasis formation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:66–8. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isacsson G, Isberg A, Haverling M, Lundquist PG. Salivary calculi and chronic sialoadenitis of the submandibular gland: A radiographic and histologic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:622–7. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oteri G, Procopio RM, Cicciù M. Giant salivary gland calculi (GSGC): Report of two cases. Open Dent J. 2011;5:90–5. doi: 10.2174/1874210601105010090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]