Abstract

Populations of African ancestry continue to account for a disproportionate burden of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) epidemic in the US. We investigated the effects of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I markers in association with virologic and immunologic control of HIV-1 infection among 338 HIV-1 subtype B-infected African Americans in two cohorts: REACH (Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health) and HERS (HIV Epidemiology Research Study). One-year treatment-free interval measurements of HIV-1 RNA viral loads and CD4+ T-cells were examined both separately and combined to represent three categories of HIV-1 disease control (76 “controllers,” 169 “intermediates,” and 93 “non-controllers”). Certain previously or newly implicated HLA class I alleles (A*32, A*36, A*74, B*14, B*1510, B*3501, B*45, B*53, B*57, Cw*04, Cw*08, Cw*12, and Cw*18) were associated with one or more of the endpoints in univariate analyses. After multivariable adjustments for other genetic and non-genetic risk factors of HIV-1 progression, the subset of alleles more strongly or consistently associated with HIV-1 disease control included A*32, A*74, B*14, B*45, B*53, B*57, and Cw*08. Carriage of infrequent HLA-B but not HLA-A alleles was associated with more favorable disease outcomes. Certain HLA class I associations with control of HIV-1 infection span the boundaries of race and viral subtype; while others appear confined within one or the other of those boundaries.

Keywords: HLA class I, Allele frequency, HIV-1 control, African American

Introduction

Human genetic polymorphism contributes to individualized responses during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Those on chromosome 6 [1] encoding human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I molecules confer the strongest and most consistent effects [2]. Numerous reports describe associations of HLA class I polymorphism with clinical, virologic, and immunologic endpoints in the course of HIV-1 infection. However, relatively few of those associations have been systematically replicated across human ethnic groups and viral subtypes (e.g., HLA-B*57 [3–10]), and many have not been reproduced, perhaps in part because of their restriction to certain ethnicities or viral subtypes [11–13]. Although African Americans bear a disproportionate burden of HIV-1 infection in the US [14, 15], the information on the role of HLA in HIV-1 subtype infection among this minority population has remained relatively limited [16, 17]. The major aim of this research was to assess the impact of class I variants in individuals in two cohorts of African ancestry in the US: REACH (Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health) and HERS (HIV Epidemiology Research Study). We have recently documented the relative contributions of HLA class I supertypes and their individual component alleles in these cohorts, confirming the association of less frequent supertypes with more favorable virologic and immunologic profiles [18]. The exploration of the effect of supertype frequency incorporated the contribution of individual alleles to the variability of influence across supertypes. Here we have more directly and systematically examined the joint and separate contributions class I alleles based on the linkage disequilibrium (LD) across A, B, and C alleles in our cohort of African Americans. We also have highlighted the noteworthy cross-population differences in the apparent effects of the Px/PY-binding B*35/*53 alleles.

Subjects and methods

Study population

We studied 338 women and adolescents from the HERS and REACH cohorts who identified themselves as African Americans on the original study questionnaires. REACH is a cohort of the HIV-1 infected adolescents from fifteen locations in thirteen US cities. The details of the REACH cohort design and data structure were previously described [19–21]. In brief, all study subjects had at least two consecutive HIV-1 RNA viral load (VL) and CD4+ T-cell (CD4) measurements during 12-week antiretroviral treatment (ART)-free intervals within the first 3 years of patient follow-up. This ART-free interval has been shown to be sufficient for the vast majority of treated individuals to return to VL set point [22]. The current study included a subset of 161 African Americans, representative of all HIV-1-positive African Americans from REACH cohort according to demographic patient characteristics (median age, 18 years; females, 81%).

Similarly, 177 African American women from HERS cohort [23] were selected from the non-random subset of 286 women with various races and ethnicities (61.9% African Americans) with fully resolved HLA class I data by established technique [16], and consecutive VL and CD4 measurements during the ART-free time intervals. Demographically, our selected HERS participants appeared to successfully represent all African Americans within the full HERS cohort that comprised 831 HIV-1-positive women (60.3% African Americans). In addition, our subset did not differ from the full cohort by the number of subjects with CD4 > 200 cells/ml (P > 0.2).

Demographic, behavioral, clinical, as well as genetic data were available for analyses of the combined African American cohort. CCR chemokine receptor genotyping was accomplished by established PCR-based technique [24].

HIV-1 outcomes

We used consecutive VL and CD4 measurements for the analysis of longitudinal data. For the purposes of categorical analysis of HIV-1 control, we grouped our study subjects into “controllers” (n = 76), “non-controllers” (n = 93), and “intermediates” (n = 169), based on favorable (VL < 1,000 copies/ml and CD4 > 450 cells/ml), unfavorable (VL > 16,000 copies/ml and CD4 < 450 cells/ml), and remaining VL and CD4 combinations, correspondingly [16]. The quantification assay of VL in HERS was performed by Quantiplex b-DNA (Chiron Corp., Emeryville, CA), whereas Nucleic Acid Sequence-Based Amplification (NASBA; NucliSens, Organon, Teknika, Durham, NC) was used for VL quantification in REACH. In direct comparisons, the latter has yielded consistently higher copy numbers than the former [25, 26]. CD4 counts were measured according to AIDS Clinical Trials Group standard flow cytometry protocol.

Statistical methods

Distribution of HLA class I alleles was tested for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in PopGen 1.32 (Alberta, Canada, http://www.ualberta.ca/~fyeh/-pr01.htm) and the HLA class I halplotypes were derived based on the estimated LD among closely related HLA class I loci. Only alleles with the population (2N) frequency equal and above 2% were considered for the LD analysis to insure the credibility of statistical estimates.

Ordinal HIV-1 control groups were analyzed by Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2 and proportional-odds logistic regression. The associations between the genetic markers and continuous repeated VL and CD4 measurements were tested by linear growth models (aka random coefficients models [27]). The effects of the individual HLA class I alleles and CCR haplotypes were tested for significant changes in VL and CD4 throughout three consecutive patient visits. In the absence of differential association between HLA alleles and HIV-1 outcomes throughout time, the estimates of HLA class I effects were chosen to reflect the average differences within the study follow-up. For the alleles which were significantly associated with patient visit, the differences at the first visit along with the estimated changes per visit were reported. These estimates were further adjusted for the effects of an individual cohort (REACH served as a referent cohort), patient age, and an interaction term between an allele and a patient visit. We used the unstructured correlation matrix to achieve the best model fit as assessed by the lowest Akaike Information Criterion, SAS 9.1.3 (Statistical Analysis Software® Institute, Cary, NC).

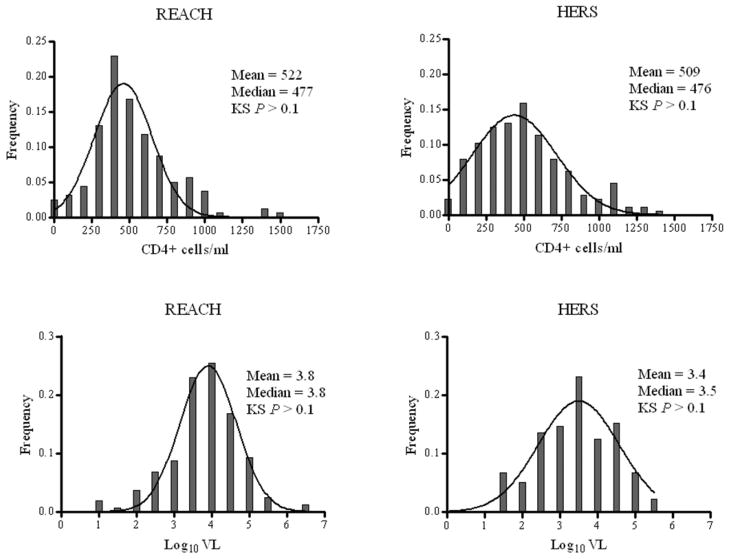

We stabilized the estimates with multiple imputations method using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo technique [28] to impute 24 missing VL and 38 missing CD4 values. Normality assumptions for all continuous variables were validated by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, SAS. VL distribution was normalized by log10 VL transformation.

HLA-A and HLA-B alleles were dichotomized into frequent and infrequent based on their median allele frequencies in the population (5.3% for HLA-A and 4.4% for HLA-B). All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.1.3, SAS/Genetics (Statistical Analysis Software® Institute, Cary, NC). GraphPad Prism 4.0 (La Jolla, CA) was used to generate graphs. PopGene 1.32 (Alberta, Canada) was used for the LD analysis.

Although most of the hypothesized associations we tested had been reported previously, we calculated a false discovery rate (FDR) in an attempt to avoid chance associations [29]. To each test we applied two q-value thresholds: one liberal (0.2) and one more conservative (0.05).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Females (n = 307) accounted for the majority (91%) of the study population (n = 338). The average age was 27 years (median 25; range, 13–54). The average population mean and median CD4 for the study subjects at all visits were 515 cells/ml (standard deviation [SD] = 279) and 476 cells/ml (range, 0–1461), respectively. Both the mean and median log10 VL were 3.6 copies/ml (SD = 0.98; range, 1.0–6.7, respectively). Cohort-specific distributions of log10 VL and CD4 conformed to normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov P-values > 0.1, Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of continuous clinical outcomes among African Americans from REACH (1996-1998) and HER (1993-2000) study cohorts. KS, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality.

HLA-A population frequencies (Suppl. Fig. 1a) ranged from 0.3% (A*80) to 18.9% (A*02). HLA-B frequencies (Suppl. Fig. 1b) ranged from 0.2% (B*37) to 13.5% (aggregate B*15). HLA-C frequencies (Suppl. Fig. 1c) ranged from 0.9% (Cw*01) to 20.1% (Cw*04). Overall, HLA class I distributions did not differ appreciably between the REACH and HERS cohorts for HLA-A (P = 0.73), HLA-B (P = 0.46), or HLA-C (P = 0.61).

Linkage disequilibrium

Patterns of LD between A and B loci and between B and C loci were cross-validated by PopGen 1.32 and SAS/Genetics. LD estimates from PopGen were particularly stringent in that only the strongest links were generated (i.e., A*26-B*39, A*25-B*40, A*29-B*49, A*36-B*53, A*66-B*41, B*07-Cw*07, B*07-Cw*15, B*14-Cw*08, B*15-Cw*03, B*15-Cw*02, B*18-Cw*05, B*35-Cw*04, B*39-Cw*12, B*42-Cw*17, B*44-Cw*05, B*45-Cw*16, B*49-Cw*07, B*53-Cw*04, B*57-Cw*18, B*5802-Cw*06, and B*81-Cw*18). SAS/Genetics validated all of those haplotypes and generated the following additional ones: A*02-B*45, A*03-B*35, A*23-B*45, A*26-B*39, A*36-B*5802, A*6801-B*5802, A*6802-B*53, A*74-B*14, A*74-B*57, and A*74-B*5801.

Categorical analysis for HIV-1 control

Categorical univariate analysis of the class I alleles demonstrated associations between two HLA-A, six HLA-B and three HLA-C alleles and the HIV-1 control categories (Table 1). In particular, HLA-A*32 and A*74 were associated with better disease control. Three HLA-B alleles were associated with better disease control (B*14, B*5701, and B*5703) whereas three were associated with worse control (B*1510, B*3501, and B*53). Both Cw*08 and Cw*18 were associated with better control, and Cw*04 was associated with worse control. There were association trends toward control for B*52 and B*81 and toward non-control for B*07.

Table 1.

HLA class I markers in association with HIV-1 control among African Americans from REACH (1996–98) and HERS (1993–2000) cohorts

| Markers | Controllers (n = 76) | Intermediate (n = 169) | Non- controllers (n = 93) | Pa | PORb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-A | |||||

| A*29 | 2 (2.6) | 6 (3.6) | 7 (7.5) | 0.1 | 2.3 (0.9–6.2) |

| A*32 | 6 (7.9) | 5 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 0.005 | 0.2 (0.06–0.6)e |

| A*6801 | 3 (4) | 11 (6.5) | 8 (8.6) | 0.2 | 1.7 (0.7–3.7) |

| A*74 | 16 (21.1) | 25 (14.8) | 5 (5.4) | <0.005 | 0.4 (0.2–0.8)f |

| HLA-B | |||||

| B*07 | 5 (6.6) | 30 (17.8) | 16 (17.2) | 0.07 | 1.6 (0.9–2.9) |

| B*14 | 11 (14.5) | 12 (7.1) | 2 (2.2) | <0.005 | 0.3 (0.1–0.7)e |

| B*1510 | 1 (1.3) | 13 (7.7) | 9 (9.7) | 0.04 | 2.2 (1.0–5.0)g |

| B*27 | 3 (4.0) | 6 (3.6) | 3 (3.2) | 0.8 | 0.87 (0.3–2.6) |

| B*3501 | 5 (6.6) | 19 (11.2) | 16 (17.2) | 0.03 | 2.0 (1.1–3.7)g |

| B*45 | 6 (7.9) | 16 (9.5) | 11 (11.8) | 0.39 | 1.4 (0.7–2.7) |

| B*52 | 4 (5.3) | 4 (2.4) | 1 (1.1) | 0.1 | 0.3 (0.1–1.2) |

| B*53 | 9 (11.8) | 44 (26.0) | 28 (30.1) | <0.01 | 1.9 (1.2–3.0)f |

| B*5701 | 5 (6.6) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | 0.03 | 0.2 (0.05–0.8)f |

| B*5703 | 19 (25) | 8 (4.7) | 1 (1.1) | <0.0001 | 0.1 (0.05–0.2)e |

| B*81 | 5 (6.6) | 7 (4.1) | 2 (2.2) | 0.15 | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) |

| HLA-C | |||||

| Cw*04 | 15 (19.7) | 69 (40.8) | 33 (35.5) | 0.05 | 1.5 (1.0–2.3)h |

| Cw*08 | 16 (21.1) | 20 (11.8) | 4 (4.3) | <0.001 | 0.3 (0.2–0.7)e |

| Cw*18 | 11 (14.5) | 15 (8.9) | 2 (2.2) | <0.005 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7)h |

| HLA class I homozygosityc | 17 (22.4) | 35 (20.7) | 34 (36.6) | 0.025 | 1.8 (1.1–2.8)f |

| HLA-A | 4 (5.3) | 9 (5.4) | 13 (14) | 0.03 | 2.6 (1.2–5.5) |

| HLA-C | 8 (10.5) | 12 (7.1) | 16 (17.2) | 0.1 | 1.8 (0.9–3.5) |

| HLA class I frequencies | |||||

| Infrequent HLA-Ad | 54 (71.1) | 122 (72.2) | 73 (78.5) | 0.3 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) |

| Infrequent HLA-Bd | 58 (76.3) | 113 (66.9) | 56 (60.2) | 0.03 | 0.6 (0.4–0.9)f |

Assessed by rank score Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for trend

POR, proportional odds ratio with 95% confidence interval; statistical significance is shown at three levels (e P < 0.01; f 0.01 < P < 0.05; g 0.05 < P < 0.1; h P > 0.1) after adjustment for age, patient visit, cohort membership (REACH is a referent cohort), and the effects of linked class I alleles

Corresponds to the HLA class I homozygosity at any locus

Infrequent HLA class I allele carriage is based on allele frequencies below or equal to the median population frequencies for HLA-A and HLA-B alleles (5.3% and 4.4%, respectively).

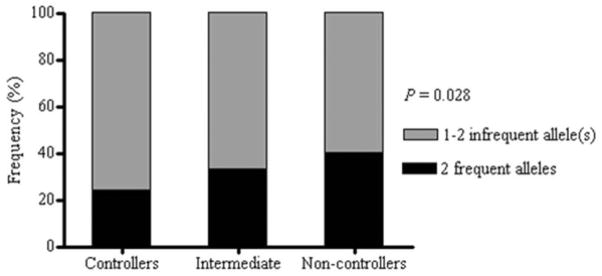

The proportion of subjects with infrequent HLA-B alleles appeared to be significantly different across the disease progression categories (P = 0.028, Fig. 2). Carriage of at least one copy of an infrequent HLA-B allele conferred significant advantage (POR 0.62; 95% CI, 0.4–0.95), but no such advantage was observed for infrequent HLA-A alleles (POR; 95% CI, 1.3, 0.8–2.1). Carriage of two infrequent B alleles (POR 0.5; 95% CI, 0.32–1.0) added little or no further advantage to carriage of a single infrequent B allele (POR 0.63; 95% CI, 0.4–1.0).

Figure 2.

Carriage of frequent and infrequent HLA-B alleles among HIV-1 control groups. Proportion of subjects carrying at least one infrequent allele differs significantly across the three incremental disease control groups (P = 0.028).

Homozygosity at any HLA class I locus was associated with non-control (POR 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1–2.8).

Analysis of repeated VLs and CD4

VL did not change significantly across patient visits for any of the HLA class I allele (all P > 0.1 for interaction with time). In the repeated CD4 analysis, only HLA-B*5703 (+40 ΔCD4, P = 0.05) and B*81 (+53 ΔCD4, P = 0.05) showed marginally significant differential associations throughout the follow-up. Overall, the estimates from the repeated measures analysis were consistent with findings from the categorical analysis even after adjustment for age, patient visit, and cohort membership (Table 2). Certain HLA class I alleles (i.e., A*32, A*74, B*14, B*53, B*5703, Cw*08, and Cw*18) were significantly associated with both VL and CD4 whereas others demonstrated association with only one or the other. Carriage of at least one infrequent HLA-B allele was associated with lower VL (−0.27 Δlog10 VL, P = 0.001) and higher ΔCD4 (+62 CD4, P = 0.05).

Table 2.

HLA class I markers in association with continuous HIV-1 outcomes among African Americans from REACH (1996–98) and HERS (1993–2000) cohorts

| Class I markers | Na | log10VL | P | CD4 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual alleles | |||||

| A*32 | 11 | −0.6 | 0.04d | +348 | <0.0001 c |

| A*36 | 19 | +0.27 | 0.24 | −153 | 0.02d |

| A*6801 | 22 | +0.16 | 0.45 | −105 | 0.08 |

| A*74 | 46 | −0.47 | 0.002d | +104 | 0.02e |

| B*14 | 25 | −0.62 | 0.002c | +180 | 0.002 c |

| B*1510 | 23 | +0.4 | 0.07 | −69 | 0.26 |

| B*1516-17 | 16 | −0.3 | 0.22 | +26 | 0.72 |

| B*27 | 12 | −0.3 | 0.28 | +78 | 0.35 |

| B*3501 | 40 | +0.34 | 0.03e | −54 | 0.25 |

| B*39 | 7 | −0.1 | 0.8 | +169 | 0.1 |

| B*45 | 33 | +0.41 | 0.02d | −85 | 0.1e |

| B*52 | 9 | −0.51 | 0.12 | +40 | 0.68 |

| B*53 | 81 | +0.27 | 0.03d | −80 | 0.02d |

| B*81 | 14 | −0.37 | 0.16 | +36 | 0.65 |

| B*5701 | 8 | −0.9 | 0.009d | +125 | 0.21 |

| B*5703 | 28 | −1.0 | <0.0001 c | +198 | <0.001 c |

| Cw*04 | 117 | +0.18 | 0.1 | −66 | 0.04f |

| Cw*07 | 119 | −0.13 | 0.24 | +60 | 0.06 |

| Cw*08 | 40 | −0.59 | <0.001 c | +158 | <0.001 c |

| Cw*12 | 9 | −0.4 | 0.22 | +285 | 0.002 c |

| Cw*18 | 28 | −0.57 | 0.002f | +193 | <0.001f |

| Haplotypes | |||||

| A*36-B*53 | 9 | +0.57 | 0.08 | −188 | 0.05f |

| A*74-B*14 | 5 | −0.93 | 0.03f | +295 | 0.02f |

| A*74-B*57 | 10 | −1.1 | <0.001f | +275 | 0.002f |

| B*14-Cw*08 | 22 | −0.65 | 0.002f | +200 | 0.001f |

| B*39-Cw*12 | 5 | −0.63 | 0.14 | +250 | 0.05f |

| B*57-Cw*18 | 15 | −1.0 | <0.0001f | +375 | <0.0001 c |

| B*35-Cw*04 | 32 | +0.18 | 0.3 | −30 | 0.6 |

| Homozygosityb | 86 | +0.3 | 0.017d | −36 | 0.3 |

| Allele frequencies | |||||

| Infrequent HLA-Aa | 249 | +0.16 | 0.1 | −60 | 0.1 |

| Infrequent HLA-Ba | 227 | −0.27 | 0.001d | +62 | 0.05d |

Note: Estimates correspond to average differences during the follow up, except for the markers differentially associated with CD4 across patient visits (B*81 and B*5703) in which case the difference at the first visit is presented along with average change in CD4 per visit (+53 CD4, P = 0.05 for B*81; +40 CD4, P = 0.05 for B*5703)

Based on allele carriage; infrequent HLA-A ( ≤ 5.3%) and -B (≤ 4.4%) alleles are based on the median population frequencies

HLA class I homozygosity at any locus

P < 0.01;

0.01 < P < 0.05;

0.05 < P < 0.1;

P > 0.1 after adjustment for age, patient visit, cohort membership (REACH is a referent cohort), and the effects of linked class I alleles.

We searched further for possible joint effects of alleles in haplotypes selected because of an observed association with one or the other of their component alleles (A*36-B*53, A*74-B*57, A*74-B*14, B*14-Cw*08, B*35-Cw*04, and B*57-Cw*18). Only the B*57-Cw*18 haplotype appeared to have a significant synergistic effect on CD4 as compared with the individual effects of B*57 or Cw*18 (P = 0.05 for interaction). The advantage of carrying Cw*18 was only apparent in the presence of B*57 (Suppl. Table 1). Subjects carrying B*14-Cw*08 (+200 ΔCD4, P = 0.001) tended to have higher absolute CD4 counts as compared to those with B*14 alone (+180 ΔCD4, P = 0.002) or Cw*08 alone (+157 ΔCD4, P = 0.001). With only three carriers of B*14 in the absence of Cw*08, we could not assess an independent effect of B*14 on HIV-1 outcomes. No interactions between the alleles of A*36-B*53, A*74-B*14, and A*74-B*57 haplotypes were detected in the linear models involving those haplotypes and their constituent alleles. In particular, A*74 carriage appeared to exert a significant and independently favorable effect on VL among subjects without B*57, B*14, or B*5801 in both stratified analysis (Supp Table 1) and multivariable analysis of the full data set with adjustment for those three B alleles.

Many of the associations with VLs paralleled those with consecutive CD4 (Table 2). Some of the associations, however, reached statistical significance only in the VL analysis (B*3501, B*45, and B*5701). HLA class I markers that remained significant in the multivariable repeated measures analysis of VL included A*32 (−0.58 Δlog10 VL, P = 0.049), A*74 (−0.33 Δlog10 VL, P = 0.02), B*14 (−0.58 Δlog10 VL, P = 0.003), B*45 (+0.36 Δlog10 VL, P = 0.02), B*53 (0.25 Δlog10 VL, P = 0.04), B*57 (−0.95 Δlog10 VL, P < 0.0001), Cw*08 (−0.59 Δlog10 VL, P < 0.001), homozygosity at any class I locus (+0.29 Δlog10 VL, P = 0.02), and infrequent HLA-B (−0.23 Δlog10 VL, P = 0.03).

B*35-Px/PY subtypes

In REACH and HERS the B*35-Px subtype (i.e., HLA-B*3502, B*3503, B*3504, and B*5301) was largely represented by B*5301 (88%) and less by B*3503 (9%) (Table 3). The association of this Px subtype was dependent exclusively on B*5301 (+0.27 log10 VL, P = 0.03); B*3503 showed a slight trend in the opposite direction for both VL and CD4. The HLA-B*35-PY subtype was represented solely by B*3501, which was associated with higher VL at a level comparable to that for Px/B*5301 (+0.34 log10 VL, P = 0.04). The associations with higher VL persisted after accounting for age, patient visit, and cohort membership; these associations were not confounded by effects of nearby alleles in LD such as HLA-A*36, A*6801, A*03, A*24, A*34, and HLA-Cw*04.

Table 3.

HLA B*35 Px and PY subtypes in association with HIV-1 outcomes among African Americans

| B*35 Px/Py alleles | Anchorsa | Nb | Δ log10VL | P | Δ CD4 | P | PORc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2 | P9 | |||||||

| Px | P | L/V | 92 | +0.23 | 0.05 | −52 | 0.1 | 1.62 (1.03–2.56) |

| B*3502 | P | M/L | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| B*3503 | P | L/V | 8 | −0.03 | 0.94 | +153 | 0.1 | 0.45 (0.13–1.6) |

| B*3504 | P | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| B*5301 | P | X | 81 | +0.27 | 0.03 | −80 | 0.02 | 1.88 (1.16–3.03) |

| Py | P | Y | 40 | +0.33 | 0.04 | −55 | 0.24 | 1.98 (1.05–3.71) |

| B*3501 | P | Y | 40 | +0.33 | 0.04 | −55 | 0.24 | 1.98 (1.05–3.71) |

| B*3508 | P | Y | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| All Px/PY | P | - | 132 | +0.32 | <0.01 | −83 | <0.01 | 2.1 (1.3–3.2) |

Note: All estimates are adjusted for patient age, visit, and cohort effect

Correspond to amino acids in epitope positions (P) 2 and 9 (P-proline, L-leucine, V-valine, M-methionine, Y-tyrosine, and X-undefined)

Corresponds to the number of subjects carrying the allele

POR, proportional odds ratio with 95% confidence interval

Discussion

Numerous studies have detected associations of individual HLA class I alleles with clinical, immunologic and virologic measures of response to HIV-1 infection, and some of these have addressed populations of African ancestry [16, 17, 30–34]. Our analysis is apparently the largest to date among women and adolescents of African-American ancestry to allow comparison of effects of class I alleles in African-Americans infected by HIV-1 subtype B with their effects in native Africans infected by subtype C. The results suggest noteworthy similarities and differences.

Among HLA-A alleles meeting the minimum 2% allele frequency for analysis, A*32 and A*74, both members of the A19 serogroup, were associated with favorable HIV-1 outcomes after adjustments for multiple alternative explanatory variants. The protective effect of A*32 found in our study has been suggested previously in primarily Caucasian populations in the context of both disease progression[3, 4, 35, 36] and response to an early construct of an HIV-1 vaccine [6]. This allele was not part of any tight B-C haplotype, and its contribution to control of disease is probably independent. A*74 also showed an advantage for all HIV-1 outcomes. Evidence of the A*74 contribution to control of HIV-1 is accumulating [37, 38]. In our cohort A*74 formed haplotypes with B*14, B*57, and B*5801; however, the effect of A*74 remained significant after adjustments for those linked alleles in multivariable analysis. Together with earlier findings, our demonstration of this association in African Americans with subtype B infection in suggests that this allele confers some protection on persons of African ancestry infected with any of several viral subtypes. Similar effects for A*32 and A*74 may reflect their shared preferences for certain HIV-1 epitope(s) [39].

The unfavorable association with A*36 here was limited to certain disease outcomes but corroborated the reports in native Africans infected with subtype C [30, 37, 40]. In contrast, A*29 had also previously shown an unfavorable effect on disease progression in some groups of Caucasians with subtype B but not in South Africans with subtype C infection [11].

Among the individual HLA-B alleles in our study, B*57 was consistently associated with virologic and immunologic control. The protective effect of B*57 has been conclusively established in virtually every setting where it occurs [8, 10, 16–18, 30, 31, 34, 35, 41–43]. The trends towards better HIV-1 control among B*81 carriers, although not statistically significant, have been documented more than once among subtype C-infected native Africans [10, 31, 34]. For both B*57 and B*81 there have been suggestions here and elsewhere [10, 31, 34, 40] that the Cw*18 allele in strong LD with both B alleles may confer a synergistic or possibly an independent effect. Protection by B*14 has also been observed before [34], albeit less uniformly and usually in subtype B- infected Caucasians [11, 44]. In our African American cohorts, the association with B*14 was independent of the association with closely linked A*74, but its effect could not be dissociated from that of the extremely tightly linked Cw*08. As for B*39 and Cw*12, population frequencies of these alleles alone or in combination have been too low for an adequate assessment of their relative contributions.

We did not observe the protective effect of B*13 seen in Africans with subtype C [45] or in an ethnically mixed North American population with subtype B infection [42]. There was only a modest trend toward association with lower VL and higher CD4 in the adjusted multivariable analyses. Although a strong protective effect of B*27 has been observed in Caucasians, relatively few African Americans in our study carried B*27 (n = 12). The ambiguous findings with B*27 here resembled those made earlier in subtype B-infected North Americans of varied racial and ethnic backgrounds [46].

Several HLA-B alleles were associated with unfavorable outcomes. The association between B*45 and higher VL in our study paralleled similar finding in both Zambians [30] and South Africans [31] infected with HIV-1 subtype C. The association of HLA-B*1510 with relatively poor control was consistent with the trend toward the higher VL seen in the study of subtype C-infected South Africans [31], in whom certain cross-reacting Gag p24 residues were restricted by B*1510, B*57, and B*5801. Escape mutations in those residues (i.e., Gag 145 and 146) may have been driven by strong evolutionary pressure from B*57 [45] at the expense of less effective binding or presentation by B*1510.

The entire B*35/B*53 allele group was associated with overall poor virologic and immunologic control. That pattern more closely resembled the results in both an ethnically mixed cohort with untreated and treated subtype B infection [42] and the comparison of disease controllers with disease progressors of African ancestry [34] than the earlier observations of a selective disadvantage of Px compared with PY alleles in both African Americans and European Caucasians [7]. In our cohort B*5301 (Px) and B*3501 (PY) were the most frequent alleles within their respective Px and PY groups, and the two alleles were equally disadvantageous. On the other hand, these clearly deleterious effects of the B*35/B*53 allele group in subtype B infection contrast strikingly with the complete absence of any effect in South Africans with subtype C infection [10, 31].

The differences in the effects of Px-PY alleles reported here and elsewhere did not depend on their corresponding HLA-C alleles; the great majority of all B*35/B*53 alleles are in tight LD with Cw*04, for which no effect independent of its paired B alleles has been detected in the past [3, 12] or in our present study. In our population of African Americans the confidence intervals around the estimate for the B*35-PY association included estimates in a range similar to those reported for Px alleles in Caucasians. In an effort to add further immunologic plausibility to the Px-PY differences, an investigation focusing on carriers of B*35-Px and -PY alleles showed that the quality of their CTL responses differed substantially despite comparable viral loads, CD4 cell counts, and quantitative CTL responses[47]. Whether subtype B-infected African Americans would display similar qualitative CTL differences perhaps reflecting distinctive patterns of escape mutation driven by other class I alleles remains to be evaluated. Another possible contributing factor is that our two African American cohorts were assembled later in the HIV-1 epidemic in the US when the prevalent viral strains might have evolved to escape the immune pressure of the relatively common HLA B*35/B*53 allele group. Our noteworthy finding of equivalence between B35*/B*53Px and PY could not have occurred falsely unless PY carriers had enrolled enough earlier to progress to the stage of the Px carriers at the time the latter enrolled. The possibility of that sequence of events seems remote.

We reconfirmed the association of HLA class I homozygosity with poor disease outcome [12, 16, 46, 48], including a potentially somewhat stronger effect of homozygosity at the A locus, as observed in HIV-1 subtype A-infected Rwandans [48].

Our study in African Americans corroborated the frequency-dependent effect of HLA class I alleles previously demonstrated among Caucasians and Asians [46, 49, 50]. In contrast to the additive algorithms typically applied (i.e., scoring based on aggregated HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C population frequencies), we categorized A and B alleles into “frequent” or “infrequent,” based on the population frequencies above and below the median for A and B alleles. In this way, HLA class I frequency definitions were not only locus-specific, but they were also based on true population frequency values. Thus, the overall effect of infrequent B alleles could be readily interpreted in the context of rare HLA-B advantage. Our findings on infrequent HLA-B allele(s) were most consistent with the dominant genetic model, where the presence of one versus two alleles makes little difference. In order to further validate our findings, we redefined our arbitrary cutoff for the “infrequent” HLA-B alleles as the lower quartile value (2.2%) for the population frequency distribution. In this sensitivity analysis the models remained largely unchanged.

The methodologic limitations of this study are most unlikely to have produced systematically spurious results. The duration of infection at enrollment in these cohorts of seroprevalent individuals was unknown. However, a haphazard distribution of pre-enrollment lengths of seropositivity with respect to the genetic markers would have more likely obscured true associations than introduced false positive ones. Similarities in CD4 cell counts along with the highly comparable frequency distributions of HLA class I alleles justified combining the two cohorts. Differences in the VL distributions in the two cohorts were due to methodologic differences for quantifying HIV-1 RNA; the NASBA/NucliSens method predictably yielded higher mean values in REACH than the b-DNA/Roche Amplicor method did in HERS [25, 26]. Nevertheless, we adjusted the analyses for cohort membership. Multiple hypothesis testing is an improbable explanation for the relationships highlighted here. Most of the associations tested had been reported previously, nearly all met the more liberal FDR threshold, and about half of them met the more conservative one (Suppl. Table 2).

Our investigation revealed important similarities and differences between populations of African and European ancestry and/or between HIV-1 subtype B and C infection in the associations of HLA class I alleles with virologic and immunologic control. In addition to the more established and dominant effects of HLA-B alleles, we confirmed certain associations with HLA-A and HLA-C alleles previously suggested only more tenuously. Coupled with the further demonstration of the importance of HLA class I supertype [18], this analysis reinforced the concept of allele and supertype frequency-dependent responses to subtype B infection. Continued research across both racial boundaries and viral subtypes will further resolve the roles played by these two factors in the differential influences of HLA class I polymorphism on the course of HIV-1 infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with supplemental funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Health Resources and Services Administration. HERS was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, and the National Institutes of Health Office for Women’s Research. Additional funding came from NIAID grants AI041951 and AI071906 (to RAK and JT). We are infinitely grateful to all participants of REACH and HERS cohorts for their valuable contribution.

Appendix

The HER Study group consists of Robert S. Klein, M.D., from the Mount Sinai School of Medicine; Ellie Schoenbaum, M.D., Julia Arnsten, M.D., M.P.H., Robert D. Burk, M.D., Penelope Demas, Ph.D., and Andrea Howard, M.D., M.Sc., from Montefiore Medical Center and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine; Paula Schuman, M.D., Jack Sobel, M.D., and Wayne Lancaster Ph.D., from the Wayne State University School of Medicine; Anne Rompalo, M.D., David Vlahov, Ph.D. and David Celentano, Ph.D., from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Charles Carpenter, M.D., Kenneth Mayer, M.D., Susan Cu-Uvin, M.D., Timothy Flanigan, M.D., Joseph Hogan, Sc.D., and Josiah Rich, M.D. from the Brown University School of Medicine; Lytt I. Gardner, Ph.D., Chad Heilig, Ph.D., Scott D. Holmberg, M.D., Denise J. Jamieson, M.D., M.P.H., Janet S. Moore, Ph.D., and Dawn K. Smith, M.D., M.P.H. from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and Katherine Davenny, M.P.H. from the National Institute of Drug Abuse.

References

- 1.Campbell RD, Trowsdale J. Map of the human MHC. Immunol Today. 1993;14(7):349. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90234-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaslow RA, McNicholl JK, Hill AVS. Genetic Susceptibility to Infectious Diseases. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaslow RA, Carrington M, Apple R, Park L, Munoz A, Saah AJ, Goedert JJ, Winkler C, O’Brien SJ, Rinaldo C, Detels R, Blattner W, Phair J, Erlich H, Mann DL. Influence of combinations of human major histocompatibility complex genes on the course of HIV-1 infection. Nat Med. 1996;2(4):405. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keet IP, Tang J, Klein MR, LeBlanc S, Enger C, Rivers C, Apple RJ, Mann D, Goedert JJ, Miedema F, Kaslow RA. Consistent associations of HLA class I and II and transporter gene products with progression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in homosexual men. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(2):299. doi: 10.1086/314862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein MR, Keet IP, D’Amaro J, Bende RJ, Hekman A, Mesman B, Koot M, de Waal LP, Coutinho RA, Miedema F. Associations between HLA frequencies and pathogenic features of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in seroconverters from the Amsterdam cohort of homosexual men. J Infect Dis. 1994;169(6):1244. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.6.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaslow RA, Rivers C, Tang J, Bender TJ, Goepfert PA, El Habib R, Weinhold K, Mulligan MJ. Polymorphisms in HLA class I genes associated with both favorable prognosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 infection and positive cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses to ALVAC-HIV recombinant canarypox vaccines. J Virol. 2001;75(18):8681. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.18.8681-8689.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao X, Nelson GW, Karacki P, Martin MP, Phair J, Kaslow R, Goedert JJ, Buchbinder S, Hoots K, Vlahov D, O’Brien SJ, Carrington M. Effect of a single amino acid change in MHC class I molecules on the rate of progression to AIDS. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(22):1668. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costello C, Tang J, Rivers C, Karita E, Meizen-Derr J, Allen S, Kaslow RA. HLA-B*5703 independently associated with slower HIV-1 disease progression in Rwandan women. Aids. 1999;13(14):1990. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910010-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flores-Villanueva PO, Yunis EJ, Delgado JC, Vittinghoff E, Buchbinder S, Leung JY, Uglialoro AM, Clavijo OP, Rosenberg ES, Kalams SA, Braun JD, Boswell SL, Walker BD, Goldfeld AE. Control of HIV-1 viremia and protection from AIDS are associated with HLA-Bw4 homozygosity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(9):5140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071548198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazaryan A, Lobashevsky E, Mulenga J, Karita E, Allen S, Tang J, Kaslow RA. Human leukocyte antigen B58 supertype and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in native Africans. J Virol. 2006;80(12):6056. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02119-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendel H, Caillat-Zucman S, Lebuanec H, Carrington M, O’Brien S, Andrieu JM, Schachter F, Zagury D, Rappaport J, Winkler C, Nelson GW, Zagury JF. New class I and II HLA alleles strongly associated with opposite patterns of progression to AIDS. J Immunol. 1999;162(11):6942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrington M, Nelson GW, Martin MP, Kissner T, Vlahov D, Goedert JJ, Kaslow R, Buchbinder S, Hoots K, O’Brien SJ. HLA and HIV-1: heterozygote advantage and B*35-Cw*04 disadvantage. Science. 1999;283(5408):1748. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geczy AF, Kuipers H, Coolen M, Ashton LJ, Kennedy C, Ng G, Dodd R, Wallace R, Le T, Raynes-Greenow CH, Dyer WB, Learmont JC, Sullivan JS. HLA and other host factors in transfusion-acquired HIV-1 infection. Hum Immunol. 2000;61(2):172. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(99)00142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glynn MKRP. Estimated HIV prevalence in the United States at the end of 2003. Presented at the 2005 National HIV Prevention Conference; Atlanta, GA. 2005. (Abstract T1-B1101) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, Karon J, Brookmeyer R, Kaplan EH, McKenna MT, Janssen RS. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. Jama. 2008;300(5):520. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang J, Wilson CM, Meleth S, Myracle A, Lobashevsky E, Mulligan MJ, Douglas SD, Korber B, Vermund SH, Kaslow RA. Host genetic profiles predict virological and immunological control of HIV-1 infection in adolescents. Aids. 2002;16(17):2275. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211220-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelak K, Goldstein DB, Walley NM, Fellay J, Ge D, Shianna KV, Gumbs C, Gao X, Maia JM, Cronin KD, Hussain SK, Carrington M, Michael NL, Weintrob AC. Host determinants of HIV-1 control in African Americans. J Infect Dis. 201(8):1141. doi: 10.1086/651382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazaryan A, Song W, Lobashevsky E, Tang J, Shrestha S, Zhang K, Gardner LI, McNicholl JM, Wilson CM, Klein RS, Rompalo A, Mayer K, Sobel J, Kaslow RA. Human leukocyte antigen class I supertypes and HIV-1 control in African Americans. J Virol. 84(5):2610. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01962-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers AS, Futterman DK, Moscicki AB, Wilson CM, Ellenberg J, Vermund SH. The REACH Project of the Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network: design, methods, and selected characteristics of participants. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22(4):300. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vermund SH, Wilson CM, Rogers AS, Partlow C, Moscicki AB. Sexually transmitted infections among HIV infected and HIV uninfected high-risk youth in the REACH study. Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(3 Suppl):49. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson CM, Houser J, Partlow C, Rudy BJ, Futterman DC, Friedman LB. The REACH (Reaching for Excellence in Adolescent Care and Health) project: study design, methods, and population profile. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(3 Suppl):8. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skiest DJ, Su Z, Havlir DV, Robertson KR, Coombs RW, Cain P, Peterson T, Krambrink A, Jahed N, McMahon D, Margolis DM. Interruption of antiretroviral treatment in HIV-infected patients with preserved immune function is associated with a low rate of clinical progression: a prospective study by AIDS Clinical Trials Group 5170. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(10):1426. doi: 10.1086/512681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith DK, Warren DL, Vlahov D, Schuman P, Stein MD, Greenberg BL, Holmberg SD. Design and baseline participant characteristics of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemiology Research (HER) Study: a prospective cohort study of human immunodeficiency virus infection in US women. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(6):459. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Downer MV, Hodge T, Smith DK, Qari SH, Schuman P, Mayer KH, Klein RS, Vlahov D, Gardner LI, McNicholl JM. Regional variation in CCR5-Delta32 gene distribution among women from the US HIV Epidemiology Research Study (HERS) Genes Immun. 2002;3(5):295. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin HJ, Pedneault L, Hollinger FB. Intra-assay performance characteristics of five assays for quantification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in plasma. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(3):835. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.835-839.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy DG, Cote L, Fauvel M, Rene P, Vincelette J. Multicenter comparison of Roche COBAS AMPLICOR MONITOR version 1.5, Organon Teknika NucliSens QT with Extractor, and Bayer Quantiplex version 3.0 for quantification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in plasma. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(11):4034. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4034-4041.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer JD. Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1998;24(4):323. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schunk D. A Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm for multiple imputation in large surveys Schunk. AStA Advances in Statistical Analysis. 2008 Feb;92(1):101. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(16):9440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang J, Tang S, Lobashevsky E, Myracle AD, Fideli U, Aldrovandi G, Allen S, Musonda R, Kaslow RA. Favorable and unfavorable HLA class I alleles and haplotypes in Zambians predominantly infected with clade C human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2002;76(16):8276. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.16.8276-8284.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiepiela P, Leslie AJ, Honeyborne I, Ramduth D, Thobakgale C, Chetty S, Rathnavalu P, Moore C, Pfafferott KJ, Hilton L, Zimbwa P, Moore S, Allen T, Brander C, Addo MM, Altfeld M, James I, Mallal S, Bunce M, Barber LD, Szinger J, Day C, Klenerman P, Mullins J, Korber B, Coovadia HM, Walker BD, Goulder PJ. Dominant influence of HLA-B in mediating the potential co-evolution of HIV and HLA. Nature. 2004;432(7018):769. doi: 10.1038/nature03113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goulder PJ. Rapid characterization of HIV clade C-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in infected African children and adults. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;918:330. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacDonald KS, Fowke KR, Kimani J, Dunand VA, Nagelkerke NJ, Ball TB, Oyugi J, Njagi E, Gaur LK, Brunham RC, Wade J, Luscher MA, Krausa P, Rowland-Jones S, Ngugi E, Bwayo JJ, Plummer FA. Influence of HLA supertypes on susceptibility and resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(5):1581. doi: 10.1086/315472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Major Genetic Determinants of HIV-1 Control Affect HLA Class I Peptide Presentation. Science. doi: 10.1126/science.1195271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trachtenberg E, Korber B, Sollars C, Kepler TB, Hraber PT, Hayes E, Funkhouser R, Fugate M, Theiler J, Hsu YS, Kunstman K, Wu S, Phair J, Erlich H, Wolinsky S. Advantage of rare HLA supertype in HIV disease progression. Nat Med. 2003;9(7):928. doi: 10.1038/nm893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fellay J, Ge D, Shianna KV, Colombo S, Ledergerber B, Cirulli ET, Urban TJ, Zhang K, Gumbs CE, Smith JP, Castagna A, Cozzi-Lepri A, De Luca A, Easterbrook P, Gunthard HF, Mallal S, Mussini C, Dalmau J, Martinez-Picado J, Miro JM, Obel N, Wolinsky SM, Martinson JJ, Detels R, Margolick JB, Jacobson LP, Descombes P, Antonarakis SE, Beckmann JS, O’Brien SJ, Letvin NL, McMichael AJ, Haynes BF, Carrington M, Feng S, Telenti A, Goldstein DB. Common genetic variation and the control of HIV-1 in humans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(12):e1000791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang J, Malhotra R, Song W, Brill I, Hu L, Farmer PK, Mulenga J, Allen S, Hunter E, Kaslow RA. Human leukocyte antigens and HIV type 1 viral load in early and chronic infection: predominance of evolving relationships. PLoS One. 5(3):e9629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koehler RN, Walsh AM, Saathoff E, Tovanabutra S, Arroyo MA, Currier JR, Maboko L, Hoelsher M, Robb ML, Michael NL, McCutchan FE, Kim JH, Kijak GH. Class I HLA-A*7401 is associated with protection from HIV-1 acquisition and disease progression in Mbeya, Tanzania. J Infect Dis. 202(10):1562. doi: 10.1086/656913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sidney J, Peters B, Frahm N, Brander C, Sette A. HLA class I supertypes: a revised and updated classification. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang J, Shao W, Yoo YJ, Brill I, Mulenga J, Allen S, Hunter E, Kaslow RA. Human leukocyte antigen class I genotypes in relation to heterosexual HIV type 1 transmission within discordant couples. J Immunol. 2008;181(4):2626. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altfeld M, Addo MM, Rosenberg ES, Hecht FM, Lee PK, Vogel M, Yu XG, Draenert R, Johnston MN, Strick D, Allen TM, Feeney ME, Kahn JO, Sekaly RP, Levy JA, Rockstroh JK, Goulder PJ, Walker BD. Influence of HLA-B57 on clinical presentation and viral control during acute HIV-1 infection. Aids. 2003;17(18):2581. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200312050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brumme C, Chui C, Woods C, Wynhoven B, Hogg R, Montaner J, Harrigan P, Brumme Z. Specific HLA-B alleles known to influence untreated HIV-1 disease progression do not appear to affect response to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 2006;17(supplement A) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Migueles SA, Sabbaghian MS, Shupert WL, Bettinotti MP, Marincola FM, Martino L, Hallahan CW, Selig SM, Schwartz D, Sullivan J, Connors M. HLA B*5701 is highly associated with restriction of virus replication in a subgroup of HIV-infected long term nonprogressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(6):2709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050567397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Magierowska M, Theodorou I, Debre P, Sanson F, Autran B, Riviere Y, Charron D, Costagliola D. Combined genotypes of CCR5, CCR2, SDF1, and HLA genes can predict the long-term nonprogressor status in human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected individuals. Blood. 1999;93(3):936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Honeyborne I, Prendergast A, Pereyra F, Leslie A, Crawford H, Payne R, Reddy S, Bishop K, Moodley E, Nair K, van der Stok M, McCarthy N, Rousseau CM, Addo M, Mullins JI, Brander C, Kiepiela P, Walker BD, Goulder PJ. Control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is associated with HLA-B*13 and targeting of multiple gag-specific CD8+ T-cell epitopes. J Virol. 2007;81(7):3667. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02689-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brumme ZL, Brumme CJ, Chui C, Mo T, Wynhoven B, Woods CK, Henrick BM, Hogg RS, Montaner JS, Harrigan PR. Effects of human leukocyte antigen class I genetic parameters on clinical outcomes and survival after initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(11):1694. doi: 10.1086/516789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin X, Gao X, Ramanathan M, Jr, Deschenes GR, Nelson GW, O’Brien SJ, Goedert JJ, Ho DD, O’Brien TR, Carrington M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific CD8+-T-cell responses for groups of HIV-1-infected individuals with different HLA-B*35 genotypes. J Virol. 2002;76(24):12603. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12603-12610.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang J, Costello C, Keet IP, Rivers C, Leblanc S, Karita E, Allen S, Kaslow RA. HLA class I homozygosity accelerates disease progression in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1999;15(4):317. doi: 10.1089/088922299311277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scherer A, Frater J, Oxenius A, Agudelo J, Price DA, Gunthard HF, Barnardo M, Perrin L, Hirschel B, Phillips RE, McLean AR. Quantifiable cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses and HLA-related risk of progression to AIDS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(33):12266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404091101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen L, Chaowanachan T, Vanichseni S, McNicholl JM, Mock PA, Nelson R, Hodge TW, van Griensven F, Choopanya K, Mastro TD, Tappero JW, Hu DJ. Frequent human leukocyte antigen class I alleles are associated with higher viral load among HIV type 1 seroconverters in Thailand. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(2):1318. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000127059.98621.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.