Abstract

Rationale: Tuberculosis (TB) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, thus there is an urgent need for novel TB vaccines.

Objectives: We investigated a novel TB vaccine candidate, M72/AS01, in a phase IIa trial of bacille Calmette-Guérin–vaccinated, HIV-uninfected, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)–infected and -uninfected adults in South Africa.

Methods: Two doses of M72/AS01 were administered to healthy adults, with and without latent Mtb infection. Participants were monitored for 7 months after the first dose; cytokine production profiles, cell cycling, and regulatory phenotypes of vaccine-induced T cells were measured by flow cytometry.

Measurements and Main Results: The vaccine had a clinically acceptable safety profile, and induced robust, long-lived M72-specific T-cell and antibody responses. M72-specific CD4 T cells produced multiple combinations of Th1 cytokines. Analysis of T-cell Ki67 expression showed that most vaccination-induced T cells did not express Th1 cytokines or IL-17; these cytokine-negative Ki67+ T cells included subsets of CD4 T cells with regulatory phenotypes. PD-1, a negative regulator of activated T cells, was transiently expressed on M72-specific CD4 T cells after vaccination. Specific T-cell subsets were present at significantly higher frequencies after vaccination of Mtb-infected versus -uninfected participants.

Conclusions: M72/AS01 is clinically well tolerated in Mtb-infected and -uninfected adults, induces high frequencies of multifunctional T cells, and boosts distinct T-cell responses primed by natural Mtb infection. Moreover, these results provide important novel insights into how this immunity may be appropriately regulated after novel TB vaccination of Mtb-infected and -uninfected individuals.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 00600782).

Keywords: tuberculosis, vaccine, T cell, cytokine, proliferation

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Approximately one-third of the world’s population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), and despite the widespread use of the bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine, tuberculosis (TB) remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality. There is an urgent need to develop novel TB vaccines that are safe, immunogenic, and effective at preventing TB in Mtb-infected and -uninfected individuals.

What This Study Adds to the Field

M72/AS01 has a clinically acceptable safety profile and is highly immunogenic in Mtb-infected and -uninfected adults. Our results demonstrate the robust capacity of the novel TB vaccine candidate M72/AS01 to induce multifunctional mycobacteria-specific T-cell responses and also rapidly boost distinct T cells primed by natural Mtb infection. These data provide strong rationale for additional trials of M72/AS01 in TB-endemic countries and in populations particularly vulnerable to TB, including adolescents and infants.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality, with approximately 9 million new cases and 1.5 million deaths worldwide each year (1). Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) provides protection against miliary TB and TB meningitis in children (2); however, BCG provides variable efficacy against pulmonary TB in adults (3), the most common clinical manifestation of the disease. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is transmitted primarily by adults; therefore novel, effective TB vaccines are urgently needed to target this population, and thereby reduce the burden of TB disease worldwide.

Phase I and II clinical trials of several novel candidate TB vaccines have either been completed or are currently ongoing (4). These vaccines include the candidate recombinant fusion protein vaccine M72, formulated with GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines proprietary Adjuvant Systems containing the immunostimulants monophosphoryl lipid A, a detoxified derivative of LPS (5), and the saponin QS21 (6). M72 is a fusion protein derived from Mtb32A and Mtb39A, antigens present in Mtb and BCG. Mtb32A and Mtb39A were selected based on their ability to stimulate T-cell responses in healthy tuberculin skin test (TST)–positive adults but not TST-negative adults (7, 8). M72 has been tested in two Adjuvant Systems, AS01 and AS02, in a phase I and II trial in Mtb-naive, TST-negative adults in Belgium (9). M72/AS01 had a clinically acceptable safety profile, and induced higher frequencies of M72-specific CD4 T cells, compared with M72/AS02 (9). Overall, these data provided rationale for further trials of M72 vaccine candidate in TB-endemic regions.

Here we investigated the safety, reactogenicity, and immunogenicity of M72/AS01 in Mtb-infected and -uninfected healthy adults living in a TB-endemic region in South Africa. We measured IL-17 and type 1 cytokine production, and induction of total cycling T-cell populations by intracellular Ki67 expression. Furthermore, to begin to investigate pathways involved in regulation of M72/AS01-induced immunity, CD25+Foxp3+ CD4 T cells were measured, and expression of the negative regulatory molecule PD-1 on M72-specific T cells. Lastly, we evaluated the effect of preexisting immunity from natural Mtb infection on the subsequent T-cell responses induced after M72/AS01 vaccination. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of a poster presentation (10).

Methods

Study Design

The study was an open-label, phase II clinical trial to evaluate the safety, reactogenicity, and immunogenicity of M72/AS01 in healthy adults with varying TST reactivity. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Cape Town and the Medicines Control Council of South Africa. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice and all applicable regulatory requirements. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, and all subjects provided written, informed consent for participation in the trial.

Study Population and Vaccination

Healthy adults aged 21–40 years were recruited from the Worcester region in the Western Cape province of South Africa. The following were inclusion criteria: no history of TB disease or pulmonary pathology, as confirmed by chest radiograph, and negative serology for HIV-1 antibodies. Women who were pregnant, or planning to become pregnant during the study period, were excluded. A TST (tuberculin purified protein derivative RT 23 SSI; Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark) was performed on each participant at least 2 weeks before administration of the first dose of the vaccine. M72/AS01 consisted of 10 μg M72 reconstituted with 0.5-ml dose of AS01E Adjuvant System containing 25 μg monophosphoryl lipid A (GlaxoSmithKline, Rixensart, Belgium) and 25 μg QS21 (Antigenics Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Agenus Inc., Lexington, MA) in a liposomal suspension. Each enrolled participant was vaccinated at baseline (Day 0) and again at Day 30 by intramuscular injection into the deltoid muscle of the nondominant arm.

Follow-up and Safety and Reactogenicity Evaluation

Participants were evaluated on the days of vaccination (0 and 30) and on Days 1, 7, 31, 37, 60, and 210. Blood for safety biochemistry and hematology tests was collected prevaccination (Day 0) and on Days 7, 30, 37, and 60. Participants were provided with diary cards to report adverse events (AEs) occurring within 7 days after each vaccination. Solicited local AEs included pain, redness, and swelling at the injection site, whereas solicited general AEs included fatigue, fever (>37.5°C), gastrointestinal symptoms, headache, malaise, and myalgia. Unsolicited AEs were recorded during the 30 days follow-up period after each vaccination. Serious AEs (SAEs) were collected during the entire study period. Assessment and grading of AEs are described in the online supplement.

Anti-M72 IgG Antibody Response

Anti-M72 IgG antibodies in serum were measured on Days 0, 30, 60, and 210 by ELISA, as previously described (9). Antibody titers greater than or equal to 2.8 ELISA units per milliliter were considered positive.

Whole Blood Intracellular Cytokine Staining Assay

Cell-mediated immunity was evaluated by intracellular cytokine staining on Days 0, 7, 30, 37, 60, and 210. The frequency and profile of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-17, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α–producing M72-specific T cells in whole blood was detected as previously described (11). Specific antigens and antibody panels are described in the online supplement.

T-Cell Phenotypic Analysis in Whole Blood Directly Ex Vivo

Immediately after collection, 0.5 ml heparanized whole blood was diluted in FACS Lysing Solution (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), followed by cryopreservation of fixed white blood cells. Cells were later thawed in batch and analyzed for T-cell expression of Ki67, CD45RA, CD25, and Foxp3 by flow cytometry. Antibody panels are provided in the online supplement.

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Intracellular Cytokine Staining Assay

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated and cryopreserved as previously described (9). PBMCs were later thawed for analysis of M72-specific Th1 cytokines and CD40L expression by CD4 and CD8 T cells, as previously described (9).

Data Analysis

The frequency of AEs was described per number of administered doses. For immunogenicity analyses, differences were assessed with nonparametric tests, using GraphPad Prism 5.0a (La Jolla, CA). Analysis of data is described in the online supplement.

Results

Participants

Forty-five healthy adults were enrolled in this study (Table 1). A TST was performed on all participants before vaccination, and participants were stratified according to TST induration to define Mtb infection status (<10 mm, considered to be Mtb-uninfected; ≥10 mm, considered to be Mtb-infected [12]). All participants were seronegative for HIV-1 and had no evidence of pulmonary pathology, as confirmed by chest radiograph. Each participant was vaccinated with the candidate vaccine at Days 0 and 30, except two participants: one participant became pregnant after dose 1 of the vaccine and was withdrawn from further vaccination; one other participant refused dose 2 of the vaccine.

TABLE 1.

DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF ENROLLED PARTICIPANTS

| TST < 10 mm (n = 15) | TST ≥ 10 mm (n = 30) | Overall (n = 45) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) |

4 (26.7) |

11 (36.7) |

15 (33.3) |

| Median age, yr (range, IQR) |

32 (22–40, 26–37) |

27 (21–38, 23.5–33) |

28 (21–40, 24–33.5) |

| Median TST, mm (range) |

1 (0–9) |

21 (11–55) |

16 (0–55) |

| Race, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Black |

0 (0) |

12 (40) |

12 (26.7) |

| White |

3 (25) |

0 (0) |

3 (6.7) |

| Mixed race | 12 (75) | 18 (60) | 30 (66.7) |

Definition of abbreviations: IQR = interquartile range; TST = tuberculin skin test.

Safety Profile of M72/AS01

No clinically relevant abnormal biochemical or hematologic laboratory findings were observed in any vaccinated participants (data not shown). No SAEs related to the vaccine were reported. Local and general AEs were solicited from all participants, with 44 (97.8%) out of 45 participants reporting at least one AE. Pain at the injection site was the most commonly reported solicited local AE, and there were no notable changes in the incidence of solicited local AEs from dose 1 to dose 2 of the vaccine. Grade 3 solicited local AEs were infrequently reported; all resolved within 3 days (Table 2; see Figure E1A in the online supplement).

TABLE 2.

SOLICITED LOCAL ADVERSE EVENTS REPORTED ON AT LEAST 1 DAY DURING THE 7-DAY FOLLOW-UP PERIODS AFTER EACH VACCINATION, N/(%)*

| Local AE | TST < 10 mm (n = 30)† | 95% CI‡ | TST ≥ 10 mm (n = 58)† | 95% CI‡ | Overall (n = 88)† | 95% CI‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

23 (76.7) |

57.7–90.1 |

49 (84.5) |

72.6–92.7 |

72 (81.1) |

72.2–89.2 |

| Grade 3 |

1 (3.3) |

0.1–17.2 |

3 (5.2) |

1.1–14.4 |

4 (4.5) |

1.3–11.2 |

| Redness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

13 (43.3) |

25.5–62.6 |

11 (19) |

9.9–31.4 |

24 (27.3) |

18.3–37.8 |

| Grade 3 |

2 (6.7) |

0.8–22.1 |

0 (0) |

0.0–6.2 |

2 (2.3) |

0.3–8.0 |

| Swelling |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

15 (50) |

31.3–68.7 |

11 (19) |

9.9–31.4 |

26 (29.5) |

20.3–40.2 |

| Grade 3 | 2 (6.7) | 0.8–22.1 | 3 (5.2) | 1.1–14.4 | 5 (5.7) | 1.9–12.8 |

Definition of abbreviations: AE = adverse event; CI = confidence interval; TST = tuberculin skin test.

Grade 3 defined as >50 mm.

n/%, number/percentage of doses followed by at least one type of AE.

Number of administered doses.

Exact 95% confidence interval, lower limit and upper limit range.

Most participants experienced flu-like symptoms for approximately 24 hours after vaccination. Headache was the most commonly reported solicited general AE overall. All grade 3 solicited general AEs resolved within the 7-day post-vaccination period and lasted for a maximum of 6 days. Grade 3 solicited general AEs were reported after a maximum of 5.7% of all doses; all resolved within 2 days (Table 3; see Figure E1B).

TABLE 3.

SOLICITED GENERAL ADVERSE EVENTS REPORTED ON AT LEAST 1 DAY DURING THE 7-DAY FOLLOW-UP PERIODS AFTER EACH VACCINATION, N/(%)*

| General AE | TST < 10 mm (n = 30)† | 95% CI‡ | TST ≥ 10 mm (n = 58)† | 95% CI‡ | Overall (n = 88)† | 95% CI‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

10 (33.3) |

17.3–52.8 |

22 (37.9) |

25.5–51.6 |

32 (36.4) |

26.4–47.3 |

| Grade 3 |

0 (0) |

0.0–11.6 |

0 (0) |

0.0–6.2 |

0 (0) |

0.0–4.1 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

11 (36.7) |

17.3–52.8 |

7 (12.1) |

3.9–21.2 |

18 (20.5) |

10.8–27.8 |

| Grade 3 |

2 (6.7) |

0.8–22.1 |

1 (1.7) |

0.0–9.2 |

3 (3.4) |

0.7–9.6 |

| Headache |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

12 (40) |

22.7–59.4 |

36 (62.1) |

48.4–74.5 |

48 (54.5) |

43.6–65.2 |

| Grade 3 |

2 (6.7) |

0.8–22.1 |

3 (5.2) |

1.1–14.4 |

5 (5.7) |

1.9–12.8 |

| Malaise |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

8 (26.7) |

12.3–45.9 |

12 (20.7) |

11.2–33.4 |

20 (22.7) |

14.5–32.9 |

| Grade 3 |

2 (6.7) |

0.8–22.1 |

1 (1.7) |

0.0–9.2 |

3 (3.4) |

0.7–9.6 |

| Myalgia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

9 (30.0) |

14.7–49.4 |

10 (17.2) |

8.6–29.4 |

19 (21.6) |

13.5–31.6 |

| Grade 3 |

1 (3.3) |

0.1–17.2 |

1 (1.7) |

0.0–9.2 |

2 (2.3) |

0.3–8.0 |

| Fever |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| All |

3 (10) |

2.1–26.5 |

15 (25.9) |

13.9–37.2 |

18 (20.5) |

11.7–29.1 |

| Grade 3 | 0 (0) | 0.0–11.6 | 1 (1.7) | 0.0–9.2 | 1 (1.1) | 0.0–6.2 |

Definition of abbreviations: AE = adverse event; CI = confidence interval; TST = tuberculin skin test.

Grade 3 defined as >39.5°C.

n/%, number/percentage of doses followed by at least one type of AE.

Number of administered doses.

Exact 95% confidence interval, lower limit and upper limit range.

Overall, unsolicited AEs related to the vaccination were reported after 19.3% of all doses. The most frequently reported unsolicited AEs were transient tachycardia (after 8% of overall doses) and hypertension (after 3.4% of overall doses), usually measured on the day after vaccination and resolving by next reading approximately 7 days later; none of these were regarded as clinically significant (see Table E1). No grade 3 unsolicited AEs were reported. One participant with a history of chronic tonsillitis was hospitalized for 2 days for exacerbation of tonsillitis; however, this SAE was not causally related to the vaccination and the participant recovered from this SAE within 12 days.

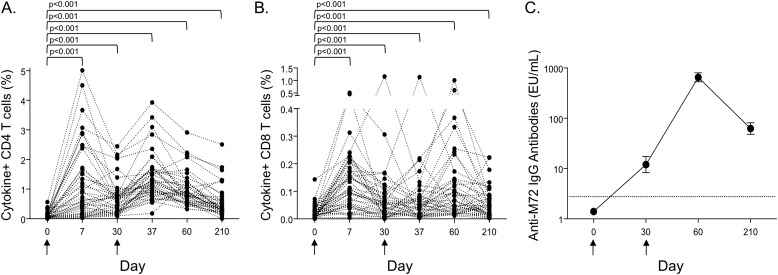

M72/AS01 Induces Robust CD4 T-Cell and IgG Antibody Responses, Which Are Boosted after the Second Vaccination

To evaluate the kinetic profiles of M72/AS01-induced immune responses, the total frequencies of M72-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells producing IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, and IL-17 were measured in whole blood by intracellular cytokine staining. The highest observed frequencies of M72-specific CD4 T cells occurred 7 days after the first vaccination, and were boosted above prevaccination frequencies after the second vaccination (Figure 1A). M72-specific CD8 T cells were also detected, with the highest frequency of cytokine-positive cells observed at Day 7 (Figure 1B). The frequency of cytokine-producing M72-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells was higher at each time point post-vaccination, compared with prevaccination levels. M72-specific IgG antibodies in serum were not detected in any participants before vaccination, but were present in all individuals by Day 60, and were maintained through Day 210 (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

M72/AS01 induces T-cell and humoral immunity. The longitudinal kinetics of M72/AS01-induced CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses were assessed by an intracellular cytokine staining assay after stimulation of whole blood with M72 protein. (A and B) The sum total frequency of IFN-γ, IL-2, tumor necrosis factor-α, and IL-17–positive CD4 and CD8 T cells; each line represents a different individual (n = 42). Results are shown after background subtraction of cytokine production in the negative control sample. (C) The geometric mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) of anti-M72 IgG antibodies in serum are shown on the day of vaccination (Day 0; n = 43), and Days 30 (n = 42), 60 (n = 43), and 210 (n = 43) after vaccination. The dotted line indicates the limit of detection of the assay (2.8 ELISA units/ml). Arrows under the x axis indicate days on which the M72/AS01 vaccine was administered.

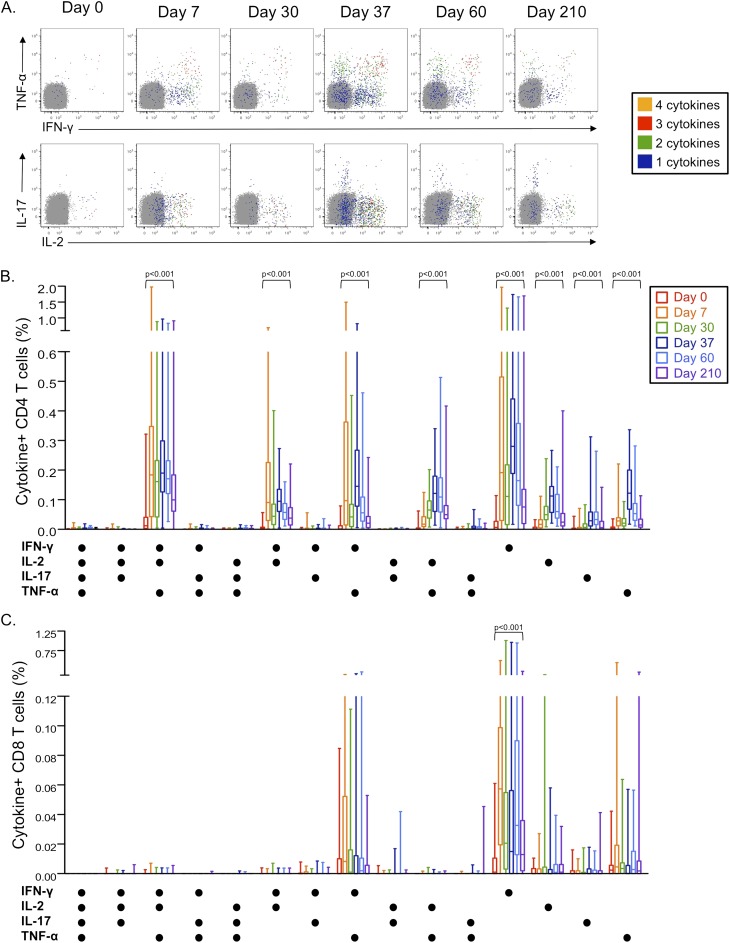

M72/AS01 Induces Complex T-Cell Responses Encompassing Multiple Populations of Cytokine-Producing CD4 and CD8 T Cells

To further define cytokine production profiles of M72-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells induced after M72/AS01 vaccination, T cells were analyzed for expression of all combinations of IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, and IL-17 in the whole blood intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assay (Figure 2A). Eight distinct subsets of cytokine-producing M72-specific CD4 T cells were identified that increased after vaccination and were maintained at significantly higher frequencies at Day 210, compared with prevaccination values. IL-17–producing CD4 T cells were induced after the second vaccination, and did not coexpress Th1 cytokines (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Vaccination with M72/AS01 induces multiple distinct populations of cytokine-producing CD4 and CD8 T cells. M72-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells producing IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-2 and IL-17 were measured by an ICS assay after stimulation of whole blood with M72 protein. (A) Representative whole blood intracellular cytokine staining flow cytometry data are shown for M72-specific CD4 T cells producing each cytokine. Plots are shown gated on CD3+CD4+ lymphocytes, with colored cells indicating populations of M72-specific CD4 T cells producing four cytokines (orange), three cytokines (red), two cytokines (green), or one cytokine (blue). The frequency of M72-specific CD4 (B) and CD8 T cells (C) producing each combination of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, and IL-17 are shown. Results are shown after subtraction of background cytokine production in the negative control sample. Statistical differences across the time points within each subset were assessed by the Friedman test. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs test was used to compare the frequency of M72-specific CD4 T-cell responses between two time points within each subset; the Wilcoxon P value is shown for comparisons between Days 0 and 210 for specific cytokine-producing CD4 and CD8 T-cell subsets.

In contrast to the complex cytokine profiles of the M72-specific CD4 T-cell response, M72-specific CD8 T cells produced predominately IFN-γ or TNF-α. Only IFN-γ single producing CD8 T cells persisted at higher frequencies by Day 210, compared with prevaccination levels (Figure 2C).

The capacity of M72/AS01 to induce multiple populations of CD4 and CD8 T cells producing Th1 cytokines, in combination with CD40L, was independently confirmed in a separate ICS assay after stimulation of cryopreserved PBMC with a pool of M72 peptides (see Figure E2).

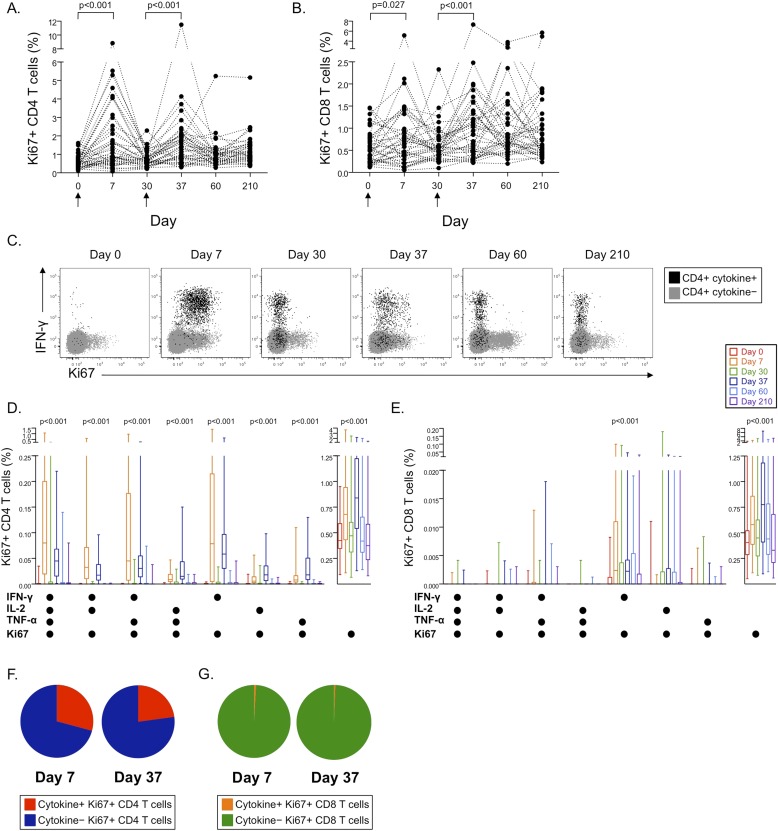

M72/AS01 Induces Populations of Cycling Ki67+ T Cells 7 Days after Vaccination, Most of Which Lack Cytokine Production Capacity

To begin to address whether specific populations of T cells were induced by M72/AS01 in addition to the Th1 and Th17 responses described previously, cell cycling was assessed by intracellular Ki67 expression in whole blood directly ex vivo. The frequencies of Ki67+ CD4 and CD8 T cells increased significantly 7 days after each vaccination, from baseline frequencies on the days of vaccination (Figures 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

Vaccination with M72/AS01 induces distinct populations of cycling Ki67+ CD4 and CD8 T cells 7 days after each vaccination. Intracellular Ki67 expression was measured in whole blood directly ex vivo at each time point for CD4 (A) and CD8 T cells (B). Differences in Ki67 expression were assessed between Days 0 and 7 and Days 30 and 37 using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs test. (C) Coexpression of Ki67 within cytokine-producing populations of M72-specific T cells was determined in the whole blood intracellular cytokine staining assay after stimulation with M72 protein. Longitudinal representative flow cytometry data are shown from a single vaccinated donor indicating coexpression patterns of Ki67 and cytokines by M72-specific CD4 T cells. Plots are shown gated on CD3+CD4+ lymphocytes. Gray dots indicate cytokine-negative CD4 T cells; black dots indicate all cytokine-positive CD4 T cells producing any combination of IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-2, or IL-17. Summary data of the frequencies of Ki67+ CD4 (D) or CD8 (E) T cells expressing each combination of cytokines, or no cytokines, are shown at each time point (n = 42). The proportions of cytokine-positive and cytokine-negative cells contributing to the total Ki67+ CD4 (F) and CD8 T-cell response (G) are shown 7 days after each vaccination. Differences in the frequencies of T cells within each subset over time were assessed using the Friedman test. Friedman test P values are shown for each subset where there was a significant difference in Ki67 expression over time.

The frequencies of Ki67+ T cells directly ex vivo were higher than those of specific cells detected by the whole blood ICS assays (see Figure E3). We therefore assessed coexpression of Ki67 in M72-specific cells detected with the whole blood ICS assay. Coexpression of Ki67 with IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 was limited to 7 days after each vaccination (Figures 3C–3E). However, most Ki67+ CD4 T cells (Figure 3F) and more than 99% of Ki67+ CD8 T cells were cytokine-negative at these time points (Figure 3G). Coexpression of Ki67 with IL-17 production was not observed (data not shown). Together, these data indicate that vaccination with M72/AS01 induces proliferation of distinct populations of T cells that lack classical Th1 or IL-17 cytokine production capacity.

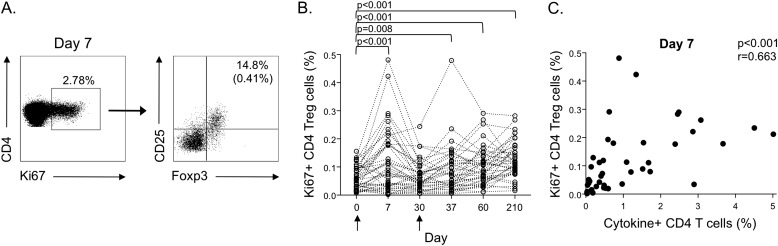

Ki67+ T Cells Induced after M72/AS01 Vaccination Contain Distinct Populations of T Cells with Regulatory Phenotypes

To further define T-cell subsets within the Ki67+ T-cell population that may contribute to the total M72/AS01-induced T-cell response, we measured the frequency of CD25+Foxp3+ T cells to identify populations of CD4 T cells with a regulatory phenotype (defined here as Tregs) in whole blood directly ex vivo (Figure 4A). Ki67+ CD4 Tregs were CD45RA− (data not shown), a phenotype consistent with that previously described of activated Tregs with proliferative and suppressive capacity (13, 14). The frequency of Ki67+ CD4 Tregs increased at Day 7 post-vaccination, coincident with the peak in cytokine-positive M72-specific CD4 T cells, and was higher at Days 7, 37, 60, and 210 post-vaccination, compared with prevaccination levels (Figure 4B). Moreover, the total frequency of cytokine-positive M72-specific CD4 T cells correlated positively with the frequency of Ki67+ CD4 Tregs at Day 7 (Figure 4C), thus indicating concomitant expansion of Tregs and cytokine-producing effector CD4 T cells after M72/AS01 vaccination.

Figure 4.

Ki67+ CD4 T cells induced after M72/AS01 vaccination contain distinct populations with regulatory phenotypes. Ki67-expressing CD4 T cells were assessed in whole blood directly ex vivo for expression of CD25, Foxp3, and CD45RA. (A) Representative flow cytometry data of CD4 Tregs (defined as CD25+Foxp3+) from a single donor at Day 7 post-vaccination. The plot on the left is gated on CD3+ T cells; the plot on the right is gated on CD3+CD4+Ki67+ cells. The percentage in the upper right quadrant indicates the percentage of Ki67+ CD4 T cells that are Tregs. The percentage in parentheses indicates the frequency of Ki67+ Tregs of the total CD4 T cell population. (B) Summary data of the frequency of Ki67+ Tregs of the total CD4 T-cell population for each donor at each time point. Differences between time points were assessed using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs test. (C) Correlation between the total frequency of M72-specific cytokine-producing CD4 T cells (cells producing IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-2, and IL-17 in whole blood after stimulation with M72 protein) and the frequency of ex vivo Ki67+ CD4 Tregs at Day 7 post-vaccination. Correlations were assessed using the Spearman rank test.

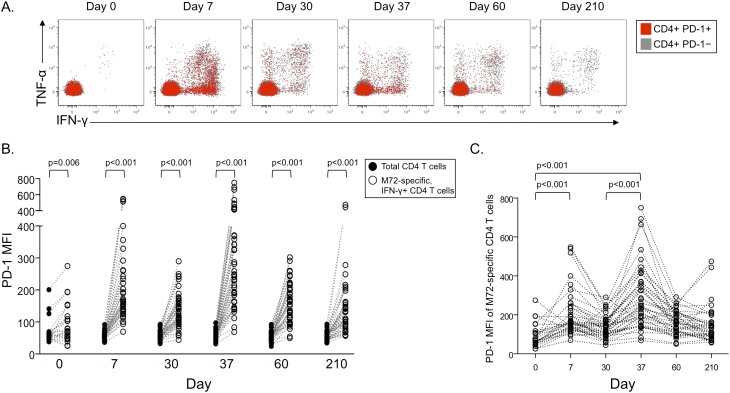

PD-1 Is Transiently Up-Regulated on M72-Specific CD4 T Cells after Vaccination with M72/AS01

To begin to identify additional regulatory pathways that may be activated after M72/AS01 vaccination, we measured expression of PD-1, a negative regulator of activated T cells (15), on M72-specific CD4 (Figure 5) and CD8 (see Figure E4) T cells in the whole blood ICS assay. PD-1 expression was increased on M72-specific IFN-γ–producing CD4 T cells (Figure 5B) and TNF-α–producing CD4 T cells (data not shown), compared with the total CD4 T-cell population, at each time point. Moreover, PD-1 expression on M72-specific CD4 T cells was transiently expressed at higher levels 7 days after each vaccination, compared with prevaccination levels (Figure 5C). By contrast, PD-1 was expressed at low levels on M72-specific CD8 T cells, and did not change over time after vaccination (see Figures E4B and E4C).

Figure 5.

PD-1 is transiently up-regulated on M72-specific CD4 T cells 7 days after each vaccination. The median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of PD-1 was measured on M72-specific T cells producing either IFN-γ or tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in whole blood after stimulation with M72 protein. (A) Representative longitudinal flow cytometry data from a single vaccinated donor; plots are gated on CD3+CD4+ lymphocytes. Gray dots indicate PD-1–negative CD4 T cells; red dots indicate PD-1–positive CD4 T cells. (B) Comparison of PD-1 MFI between total CD4 T cells (black circles) and M72-specific (IFN-γ–positive; open circles) CD4 T cells. Only individuals with IFN-γ–positive M72-specific CD4 T-cell responses are shown at each time point (Day 0, n = 24; Day 7, n = 41; Day 30, n = 41; Day 37, n = 43; Day 60, n = 43; Day 210, n = 42). Differences between PD-1 expression on total CD4 T cells and M72-specific CD4 T cells at each time point were determined by the Wilcoxon matched-pairs test. (C) Longitudinal analysis of PD-1 MFI on M72-specific IFN-γ–positive CD4 T-cell responses on an individual donor basis. Differences in PD-1 MFI on M72-specific CD4 T cells between time points were determined by the Mann-Whitney test.

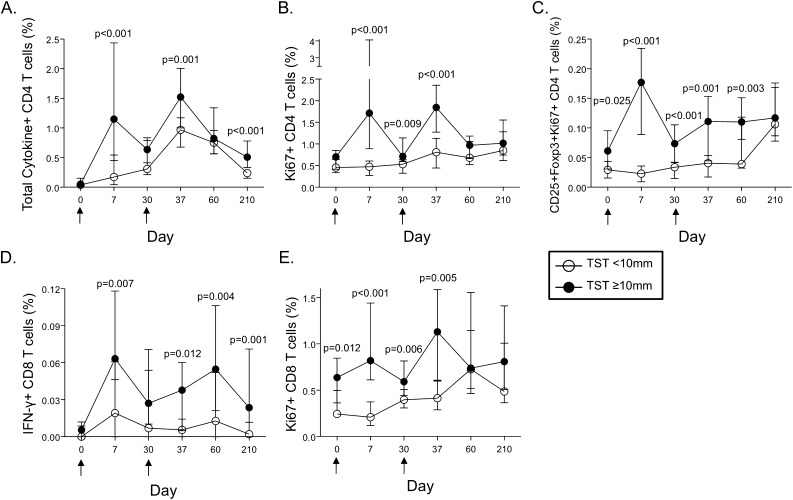

M72/AS01 Induces Higher Frequencies of T-Cell Responses in Participants Infected with Mtb Compared with Uninfected Participants

To determine the effect of pre-existing immunity primed by natural Mtb infection on the M72/AS01 vaccine-induced immune response, we compared T-cell responses induced between participants in the TST less than 10 mm (representing Mtb-uninfected) and greater than or equal to 10 mm (representing Mtb-infected) subgroups. The total frequencies of M72-specific cytokine-positive CD4 T cells and IFN-γ–positive CD8 T cells were higher in the TST greater than or equal to 10 mm subgroup, compared with the less than 10 mm subgroup, at Days 7, 37, and 210 post-vaccination (Figures 6A and 6D). In addition, of the eight distinct M72-specific CD4 T cell subsets induced after vaccination, six subsets were detected at higher frequencies in the TST greater than or equal to 10 mm subgroup, compared with less than 10 mm subgroup (see Figure E5).

Figure 6.

Increased frequencies of specific subsets of M72-specific CD4 and CD8 T cells after M72/AS01 vaccination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis–infected participants, compared with uninfected participants. M72-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses were assessed in all vaccinated donors with a whole blood intracellular cytokine staining assay, as described in Figures 1 and 2. (A) The total frequency of cytokine-producing M72-specific CD4 T cells and IFN-γ–producing M72-specific CD8 T cells (D) were compared between the tuberculin skin test (TST) less than 10 mm and greater than or equal to 10 mm subgroups (n = 14 and n = 28, respectively). (B) Comparison of the total frequency of Ki67+ CD4 T cells and Ki67+ CD4 Treg cells (C) between the TST less than 10 mm and greater than or equal to 10 mm subgroups (n = 15 and n = 26, respectively). (E) Comparison of the total frequency of Ki67+ CD8 T cells between the TST less than 10 mm and greater than or equal to 10 mm subgroups (n = 15 and n = 26, respectively). The median and interquartile ranges are shown for each group at each time point. Open circles represent the TST less than 10 mm subgroup and black circles represent the TST greater than or equal to 10 mm subgroup. For all analyses, differences between the groups at each time point were assessed by the Mann-Whitney test.

Significantly higher frequencies of Ki67+ CD4 and CD8 T cells were found in the TST greater than or equal to 10 mm subgroup, compared with the less than 10 mm subgroup (Figures 6B and 6E). Moreover, the increased frequency of Ki67+ CD4 Tregs at Day 7 post-vaccination was confined to participants in the TST greater than or equal to 10 mm subgroup (Figure 6C). However, there were no differences in PD-1 expression on M72-specific CD4 T cells between the two subgroups (see Figure E6), thus indicating the transient increase in PD-1 expression was induced by exposure to the vaccine antigen, rather than Mtb antigen exposure in vivo.

Discussion

In this phase IIa clinical trial, we report that M72/AS01 had a clinically acceptable safety profile in healthy adults in a TB-endemic region of South Africa, consistent with the safety profiles reported in previous trials of M72/AS01 and M72/AS02 conducted in Mtb-naive, TST-negative European adults (9). The major immunogenicity findings were, first, that the vaccine induced multiple populations of cytokine-producing M72-specific T cells, and cycling Ki67+ T cells, most of which lacked M72-specific cytokine production capacity ex vivo. Second, Ki67+ CD4 cells with a regulatory phenotype were induced 7 days post-vaccination, coincident with the peak of M72-specific Th1 cytokine-producing cells. Third, the immunoregulatory molecule PD-1 was transiently up-regulated on M72-specific CD4 T cells after M72/AS01 vaccination. Fourth, increased frequencies of specific populations of T cells in Mtb-infected participants, compared with Mtb-uninfected participants, provide further evidence of vaccine-mediated boosting and rapid expansion of functionally distinct T-cell populations primed by natural Mtb infection.

A striking feature of M72/AS01 is the complexity of the T-cell responses generated. At least eight distinct cytokine-producing populations of M72-specific CD4 T-cell responses were induced and persisted to at least 7 months after the first vaccination, including a discrete population of Th17 cells. Studies in mice have suggested Th17 cells play an active role in production of chemokines that recruit IFN-γ–producing CD4 T cells to the lungs to restrict mycobacterial growth after challenge (16), and may be an important component of long-term control of Mtb infection (17). Moreover, polyfunctional CD4 T cells simultaneously producing IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 in the lung have been correlated with better protection against Mtb challenge in mice (18). Although the precise immune correlates of protection against TB disease in humans remain undefined, we hypothesize that this diversity of multiple antigen-specific CD4 T-cell populations may contribute to protection against Mtb.

A novel feature of M72/AS01 is the induction of M72-specific CD8 T cells. Although the M72-specific CD8 T-cell responses were of low magnitude in the overall vaccinated cohort, there were significantly higher frequencies of IFN-γ–producing M72-specific CD8 T cells post-vaccination in participants in the TST greater than or equal to 10 mm subgroup, compared with the less than 10 mm subgroup (Figure 6D). Taken together with the lack of detectable M72-specific CD8 T cells in previous trials in Mtb-naive populations (9, 19, 20), these data suggest M72/AS01 may be more efficient at boosting preexisting CD8 T-cell responses, as opposed to the induction of CD8 T cell responses de novo.

Previous studies with two highly effective vaccines in humans, the yellow fever virus (YFV) vaccine and the smallpox vaccine, have indicated measurement of cytokine-producing T cells alone may vastly underestimate the total frequency and functional diversity of vaccine-induced T-cell responses (21). Moreover, these studies, using tetramers to detect specific cells, indicated measurement of activation markers can accurately identify vaccine-induced populations of effector CD8 T cells (21). We found a significant increase in the frequency of Ki67+ CD4 and CD8 T cells 7 days after each vaccination. The lack of ex vivo cytokine production capacity by most Ki67+ T cells in our TB vaccination setting thus agree with those in smallpox and YFV vaccination settings (21). Importantly, these data further indicate M72/AS01-mediated expansion of specific T-cell subsets with functional capacities other than type 1 or type 17 cytokine production, which could include such populations as cytotoxic T cells, regulatory T cells, Th2 cells, or T follicular helper cells (TFH).

To begin to investigate additional populations of T cells that may be present within the Ki67+ subset, we stained whole blood directly ex vivo for expression of CD25 and Foxp3, phenotypic markers commonly used to identify Tregs (22, 23). We identified cycling CD25+Foxp3+ CD4 T cells as a distinct population contributing to the total Ki67+ CD4 T-cell response observed after vaccination. The correlation between the frequencies of Ki67+CD25+Foxp3+ CD4 T cells and cytokine-producing CD4 T cells 7 days post-vaccination are consistent with previous studies reporting accumulation of Tregs in parallel with effector CD4 T cells at sites of infection (24, 25). Moreover, they are consistent with recent studies reporting parallel functional specialization of Treg and effector CD4 T-cell populations in humans (26). In clinical trials of the TB vaccine MVA85A, a positive correlation was observed between the frequency of prevaccination purified protein derivative–specific IFN-γ–producing cells and the frequency of CD25hiCD39+ CD4 T cells in adults prevaccination and post-vaccination (27), thus further underscoring the important interplay between regulatory and effector immune responses induced after vaccination.

We used coexpression of Foxp3 and CD25 to define CD4 T cells with a regulatory phenotype (22, 23); however, several previous studies in humans have reported transient up-regulation of Foxp3 expression after T-cell receptor (TCR) cross-linking in vitro, with Foxp3 expression peaking 5 to 7 days after stimulation (23, 28–30). It is possible that increased frequencies of cycling CD25+Foxp3+ CD4 T cells observed 7 days post-vaccination reflects vaccine-induced activation of effector CD4 T cells in vivo. However, induction of Foxp3 expression after TCR cross-linking in vitro has been associated with attenuation of effector functions (30), and previous studies have indicated Foxp3 can regulate T-cell activation by inhibiting nuclear factor of activated T cells–mediated transcription (31, 32). We did not have sufficient samples available to directly measure the suppressive capacity of CD25+Foxp3+Ki67+ CD4 T cells observed after vaccination. However, previous detailed functional profiling of Foxp3+ T cells in humans indicate CD45RAloFoxp3hiKi67+ CD4 T cells, consistent with the phenotype observed in our study, represent a population of activated Tregs with suppressive capacity (14). Taken together these data suggest the increased frequency of cycling CD25+Foxp3+ CD4 T cells may represent a potential mechanism contributing to regulation and subsequent contraction of effector CD4 T cells activated by M72/AS01.

Increasing evidence from human and animal models of Mtb indicates excessive inflammation or highly activated populations of CD4 Th1 cells exacerbates TB disease and promotes immunopathology (33–36), thus underscoring the critical need for a balanced regulatory and effector T-cell response for optimal control of bacterial replication while simultaneously limiting effector cell-mediated tissue damage. PD-1 was transiently expressed at high levels on M72-specific CD4 T cells 7 days after each vaccination, consistent with transient PD-1 expression on virus-specific CD8 T cells in previous studies in humans vaccinated with either YFV or smallpox vaccines (21, 37). There was no difference in PD-1 expression on M72-specific CD4 T cells in Mtb-infected and -uninfected individuals, thus strongly suggesting the transient up-regulation of PD-1 observed on M72-specific CD4 T was induced by exposure to the vaccine antigen, rather than Mtb antigen exposure in vivo.

A limitation of these findings is that we did not have sufficient samples to determine the functional consequence of PD-1 expression on M72-specific CD4 T cells. However, recent studies using single-cell imaging demonstrate that on ligation with its ligand, PD-1 clusters with the TCR and transiently associates with the phosphatase SHP2, resulting in dephosphorylation of signaling molecules and direct inhibition of T-cell activation (38). Importantly, this PD-1–mediated inhibitory mechanism was apparent in T cells activated in vitro and PD-1hi T cells generated in vivo (38). We hypothesize that transient expression of PD-1 induced by antigen exposure in a vaccination setting may be an immunoregulatory mechanism contributing to contraction of the M72-specific effector CD4 T-cell response.

An estimated one-third of the world’s population is currently infected with Mtb, thus underscoring the critical need to develop a novel TB vaccine that is safe, immunogenic, and can provide protection against development of TB disease in Mtb-infected individuals. More importantly, these individuals represent the reservoir of potential TB cases, and are thus the most relevant target population for novel TB vaccines. We observed higher frequencies of multiple populations of M72-specific cytokine-producing T cells in Mtb-infected participants, compared with Mtb-uninfected participants. Moreover, the increased frequencies of all subsets of Ki67+ T cells measured at 7 days post-vaccination, compared with prevaccination frequencies, were confined to Mtb-infected participants. These data thus provide compelling evidence of M72/AS01-mediated boosting of discrete T-cell populations primed by natural Mtb infection; moreover, they suggest that M72/AS01 may induce functionally distinct profiles of M72-specific T cells in Mtb-infected versus -uninfected individuals. These findings contrast with previously reported observations in a small clinical trial of adults vaccinated with MVA85A, in which no differences were found in the magnitude of Ag85A-specific IFN-γ–producing T cells between Mtb-infected and BCG-vaccinated, Mtb-uninfected participants after vaccination (39).

In summary, we report robust induction of humoral and cellular immunity and a clinically acceptable safety profile after M72/AS01 vaccination of Mtb-infected and -uninfected adults, with no evidence of mycobacteria-specific immunopathology after vaccination. Overall, the results from this M72/AS01 trial provide novel insights into the induction and regulation of vaccine-induced T-cell responses in Mtb-infected and -uninfected individuals; furthermore, they provide strong rationale for additional trials of M72/AS01 in TB-endemic countries and in populations particularly vulnerable to TB, including adolescents and infants.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the volunteers participating in this study, and acknowledge the contributions of clinicians, nurses, and technicians at South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative and laboratory technicians at GlaxoSmithKline. In addition, the authors thank Erik Jongert, Evi De Ruymaeker, and Blessing Kadira for their contributions to this study, and Sofia Dos Santos Mendes for providing publication coordination on behalf of GlaxoSmithKline.

Footnotes

Supported by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals S.A. and Aeras. C.L.D. is supported in part by the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409). W.A.H. is supported in part by the Wellcome Trust–funded Clinical Infectious Diseases Research Initiative.

Author Contributions: C.L.D., M.T., M.-A.D., P. Mettens, P. Moris, P.B., J.C., J.C.S., A.H., G.D.H., H.M., O.O.-A., and W.A.H. designed the study and analyzed data. M.T., M.v.R., and H.G. provided clinical help. M.T., M.v.R., M.d.K., E.J.H., S.G., M.-A.D., and P.B. managed the project. N.M., M.E., and L.M. performed laboratory assays and analysis. A.B. performed statistical analysis. C.L.D., M.T., A.B., P.B., J.C., M.-A.D., P. Mettens, P. Moris, H.M., O.O.-A., and W.A.H. wrote the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1385OC on January 10, 2013

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.World Health OrganizationGlobal tuberculosis control 2011 [accessed 2011 Dec 6]. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/index.html

- 2.Rodrigues LC, Diwan VK, Wheeler JG. Protective effect of BCG against tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis: a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22:1154–1158. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.6.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colditz GA, Brewer TF, Berkey CS, Wilson ME, Burdick E, Fineberg HV, Mosteller F. Efficacy of BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis: meta-analysis of the published literature. JAMA. 1994;271:698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rappuoli R, Aderem A. A 2020 vision for vaccines against HIV, tuberculosis and malaria. Nature. 2011;473:463–469. doi: 10.1038/nature10124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casella CR, Mitchell TC. Putting endotoxin to work for us: monophosphoryl lipid A as a safe and effective vaccine adjuvant. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3231–3240. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcon N, Van Mechelen M. Recent clinical experience with vaccines using MPL- and QS-21-containing adjuvant systems. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10:471–486. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skeiky YA, Lodes MJ, Guderian JA, Mohamath R, Bement T, Alderson MR, Reed SG. Cloning, expression, and immunological evaluation of two putative secreted serine protease antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3998–4007. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3998-4007.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dillon DC, Alderson MR, Day CH, Lewinsohn DM, Coler R, Bement T, Campos-Neto A, Skeiky YA, Orme IM, Roberts A, et al. Molecular characterization and human T-cell responses to a member of a novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mtb39 gene family. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2941–2950. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2941-2950.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leroux-Roels I, Forgus S, De Boever F, Clement F, Demoitie MA, Mettens P, Moris P, Ledent E, Leroux-Roels G, Ofori-Anyinam O.Improved CD4(+) T cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in PPD-negative adults by M72/AS01 as compared to the M72/AS02 and Mtb72F/AS02 tuberculosis candidate vaccine formulations: a randomized trial Vaccine 2013;312196–2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Day CL.Induction of robust polyfunctional T cell responses following vaccination of healthy adults with GSK's candidate TB vaccine M72/AS01E Presented at the Keystone Symposia: Overcoming the Crisis of TB and AIDS. Arusha, Tanzania, 20–25 October 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanekom WA, Hughes J, Mavinkurve M, Mendillo M, Watkins M, Gamieldien H, Gelderbloem SJ, Sidibana M, Mansoor N, Davids V, et al. Novel application of a whole blood intracellular cytokine detection assay to quantitate specific T-cell frequency in field studies. J Immunol Methods. 2004;291:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. This is a joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This statement was endorsed by the council of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. (IDSA), September 1999, and the sections of this statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:S221–S247. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_3.ats600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Booth NJ, McQuaid AJ, Sobande T, Kissane S, Agius E, Jackson SE, Salmon M, Falciani F, Yong K, Rustin MH, et al. Different proliferative potential and migratory characteristics of human CD4+ regulatory T cells that express either CD45RA or CD45RO. J Immunol. 2010;184:4317–4326. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A, Shima T, Wing K, Niwa A, Parizot C, Taflin C, Heike T, Valeyre D, et al. Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the foxp3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;30:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. The B7–CD28 superfamily. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:116–126. doi: 10.1038/nri727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khader SA, Bell GK, Pearl JE, Fountain JJ, Rangel-Moreno J, Cilley GE, Shen F, Eaton SM, Gaffen SL, Swain SL, et al. IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:369–377. doi: 10.1038/ni1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desel C, Dorhoi A, Bandermann S, Grode L, Eisele B, Kaufmann SH. Recombinant BCG deltaurec hly+ induces superior protection over parental BCG by stimulating a balanced combination of type 1 and type 17 cytokine responses. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1573–1584. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forbes EK, Sander C, Ronan EO, McShane H, Hill AV, Beverley PC, Tchilian EZ. Multifunctional, high-level cytokine-producing Th1 cells in the lung, but not spleen, correlate with protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis aerosol challenge in mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:4955–4964. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leroux-Roels I, Leroux-Roels G, Ofori-Anyinam O, Moris P, De Kock E, Clement F, Dubois MC, Koutsoukos M, Demoitie MA, Cohen J, et al. Evaluation of the safety and immunogenicity of two antigen concentrations of the Mtb72F/AS02(A) candidate tuberculosis vaccine in purified protein derivative-negative adults. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:1763–1771. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00133-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Von Eschen K, Morrison R, Braun M, Ofori-Anyinam O, De Kock E, Pavithran P, Koutsoukos M, Moris P, Cain D, Dubois MC, et al. The candidate tuberculosis vaccine Mtb72F/AS02A: tolerability and immunogenicity in humans. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5:475–482. doi: 10.4161/hv.8570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller JD, van der Most RG, Akondy RS, Glidewell JT, Albott S, Masopust D, Murali-Krishna K, Mahar PL, Edupuganti S, Lalor S, et al. Human effector and memory CD8+ T cell responses to smallpox and yellow fever vaccines. Immunity. 2008;28:710–722. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker MR, Kasprowicz DJ, Gersuk VH, Benard A, Van Landeghen M, Buckner JH, Ziegler SF. Induction of foxp3 and acquisition of T regulatory activity by stimulated human CD4+CD25- T cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1437–1443. doi: 10.1172/JCI19441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott-Browne JP, Shafiani S, Tucker-Heard G, Ishida-Tsubota K, Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY, Bevan MJ, Urdahl KB. Expansion and function of foxp3-expressing T regulatory cells during tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2159–2169. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guyot-Revol V, Innes JA, Hackforth S, Hinks T, Lalvani A. Regulatory T cells are expanded in blood and disease sites in patients with tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:803–810. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200508-1294OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duhen T, Duhen R, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F, Campbell DJ. Functionally distinct subsets of human foxp3+ Treg cells that phenotypically mirror effector Th cells. Blood. 2012;119:4430–4440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-392324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Cassan SC, Pathan AA, Sander CR, Minassian A, Rowland R, Hill AV, McShane H, Fletcher HA. Investigating the induction of vaccine-induced Th17 and regulatory T cells in healthy, Mycobacterium bovis BCG-immunized adults vaccinated with a new tuberculosis vaccine, MVA85A. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:1066–1073. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00047-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gavin MA, Torgerson TR, Houston E, DeRoos P, Ho WY, Stray-Pedersen A, Ocheltree EL, Greenberg PD, Ochs HD, Rudensky AY. Single-cell analysis of normal and foxp3-mutant human T cells: Foxp3 expression without regulatory T cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6659–6664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509484103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker MR, Carson BD, Nepom GT, Ziegler SF, Buckner JH. De novo generation of antigen-specific CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells from human CD4+CD25- cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4103–4108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407691102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Ioan-Facsinay A, van der Voort EI, Huizinga TW, Toes RE. Transient expression of foxp3 in human activated nonregulatory CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:129–138. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schubert LA, Jeffery E, Zhang Y, Ramsdell F, Ziegler SF. Scurfin (foxp3) acts as a repressor of transcription and regulates T cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37672–37679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104521200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Y, Borde M, Heissmeyer V, Feuerer M, Lapan AD, Stroud JC, Bates DL, Guo L, Han A, Ziegler SF, et al. Foxp3 controls regulatory T cell function through cooperation with NFAT. Cell. 2006;126:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barber DL, Mayer-Barber KD, Feng CG, Sharpe AH, Sher A. CD4 T cells promote rather than control tuberculosis in the absence of PD-1-mediated inhibition. J Immunol. 2011;186:1598–1607. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tobin DM, Roca FJ, Oh SF, McFarland R, Vickery TW, Ray JP, Ko DC, Zou Y, Bang ND, Chau TT, et al. Host genotype-specific therapies can optimize the inflammatory response to mycobacterial infections. Cell. 2012;148:434–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tobin DM, Vary JC, Jr, Ray JP, Walsh GS, Dunstan SJ, Bang ND, Hagge DA, Khadge S, King MC, Hawn TR, et al. The lta4h locus modulates susceptibility to mycobacterial infection in zebrafish and humans. Cell. 2010;140:717–730. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lazar-Molnar E, Chen B, Sweeney KA, Wang EJ, Liu W, Lin J, Porcelli SA, Almo SC, Nathenson SG, Jacobs WR., Jr Programmed death-1 (PD-1)-deficient mice are extraordinarily sensitive to tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13402–13407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007394107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akondy RS, Monson ND, Miller JD, Edupuganti S, Teuwen D, Wu H, Quyyumi F, Garg S, Altman JD, Del Rio C, et al. The yellow fever virus vaccine induces a broad and polyfunctional human memory CD8+ T cell response. J Immunol. 2009;183:7919–7930. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yokosuka T, Takamatsu M, Kobayashi-Imanishi W, Hashimoto-Tane A, Azuma M, Saito T. Programmed cell death 1 forms negative costimulatory microclusters that directly inhibit T cell receptor signaling by recruiting phosphatase SHP2. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1201–1217. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sander CR, Pathan AA, Beveridge NE, Poulton I, Minassian A, Alder N, Van Wijgerden J, Hill AV, Gleeson FV, Davies RJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a new tuberculosis vaccine, MVA85A, in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected individuals. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:724–733. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1486OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]