Abstract

Risk of antenatal depression has been shown to be elevated in Southern Africa and can impact maternal and child outcomes, especially in the context of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Brief screening methods may optimize access to care during pregnancy, particularly where resources are scarce. This research evaluated shorter versions of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to detect antenatal depression. This cross-sectional study at a large primary health care (PHC) facility recruited a consecutive series of 109 antenatal attendees in rural South Africa. Women were in the second half of pregnancy and completed the EPDS and Structured Clinical Interview for Depression (SCID). The recommended EPDS cutoff (≥13) was used to determine probable depression. Four versions, including the 10-item scale, seven-item depression, and novel three- and five-item versions developed through regression analysis, were evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. High numbers of women 51/109 (47 %) were depressed, most depression was chronic, and nearly half of the women were HIV positive 49/109 (45 %). The novel three-item version had improved positive predictive value (PPV) over the 10-item version and equivalent specificity to the seven-item depression subscale; the novel five-item provided the best overall performance in terms of ROC and Cronbach's reliability statistics and had improved specificity. The brevity, sensitivity, and reliability of the short and ultrashort versions could facilitate widespread community screening. The usefulness of the novel three- and five-item versions are underscored by the fact that sensitivity is important at first screening, while specificity becomes more important at higher levels of care. Replication in larger samples is required.

Keywords: Antenatal depression, Screening, EPDS, Short, Ultrashort, HIV

Introduction

Prevalence of depression is similar in pregnant, postpartum, and nonpregnant women. However, the onset of new depression is higher during the perinatal period (Vesga-Lopez et al. 2008) and postpartum depression is often preceded by antenatal symptomology (Rahman and Creed 2007; Milgrom et al. 2008). Depression during pregnancy has been associated with poor uptake of antenatal care and adverse fetal and obstetric outcomes (Lancaster et al. 2010; Alder et al. 2007; Grote et al. 2010). Increasingly, anxiety during pregnancy has also been shown to be of concern (Alder et al. 2007; Austin 2004). While increased health care contact during pregnancy provides opportunities for screening, prevention, and treatment (Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health: Task Force on Mental Health 2009), antenatal depression frequently remains undetected and untreated (Goodman and Tyer-Viola 2010).

A systematic review of perinatal mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) found a concerning burden, with weighted mean prevalence between 15 and 20 % (Fisher et al. 2012), with the review highlighting the dearth of research evidence in LMIC (Parsons et al. 2011) and in Africa (Sawyer et al. 2010), a continent also heavily affected by HIV epidemics. In the sub-Saharan African region alone, in 2010, approximately 1.36 million pregnant women were living with HIV (World Health Organization 2011); antenatal depression has been shown to be elevated in the context of HIV with rates above 40 % (Rubin et al. 2011; Rochat et al. 2011; Rochat et al. 2006). Improving early detection and intervention during routine pregnancy care may reduce risks for postnatal depression and may also improve HIV treatment and prevention outcomes (Psaros et al. 2009; Kapetanovic et al. 2009; Levine et al. 2008).

Despite significant and growing support for universal screening (Mitchell and Coyne 2007; Breedlove and Fryzelka 2011; Kim et al. 2008; Kuchn 2010), multiple challenges exist in ensuring that health care practitioners screen for depression in primary health care (PHC) and among high risk populations such as pregnant women (Gjerdingen and Yawn 2007; Kopelman et al. 2008; Rice et al. 2007). Resistance to screening is often high where primary care is particularly time pressured, creating a need for short, user-friendly, and sensitive tools. A recent pooled analysis (Mitchell and Coyne 2007) found that ultra short one-item screens have reasonable specificity, but low sensitivity, identifying only three in 10 depressed patients, while two- or three-item ultrashort measures have significantly improved sensitivity, identifying eight in 10 depressed cases. However, there are concerns that this higher sensitivity comes at the expense of high false-positive rates that prove too costly when resources are scarce. Evidence supporting the cost effectiveness of universal screening is mixed (Yonkers et al. 2009; Mitchell and Coyne 2009), with some studies showing that lack of access to treatment undermines the cost effectiveness of universal screening (Paulden et al. 2009), as does offering treatment to women who do not need it or to those who do not want it (Dowswell et al. 2010).

The issue of whether universal screening improves access to treatment, whether it is feasible, or benefits patients, is particularly complex in low-resource settings (Kagee et al. 2012; O'Hara et al. 2012). Barriers to routine screening for antenatal depression include lack of time, stigma, incomplete training, inattention by health professionals, and a lack of referral sources (Earls and The Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child Family Health 2010; Honikman et al. 2012). In LMIC settings, screening is often restricted by critical shortages in health care professionals at PHC level (Patel et al. 2009) and task shifting of primary care and prevention functions to community health care workers (CHW) is proposed as a means to improve maternal and child outcomes (Lewin et al. 2010). Approaches that incorporate CHWs in the detection and management of perinatal mental disorders have shown potential, with research demonstrating the capacity of CHWs to deliver treatment for both HIV (Selke et al. 2010) and maternal depression (Rahman 2005; Rahman et al. 2008). However, actualizing this potential at a larger scale requires short, effective screening measures to facilitate detection in two ways: firstly, by facilitating screening by CHWs who may identify risk at a household level and secondly, by facilitating screening by busy health practitioners within antenatal services. Shorter tools provide benefits from the health care perspective and have higher acceptability for women (Milgrom et al. 2011; Breedlove and Fryzelka 2011).

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) is the most widely used screening tool for the detection of perinatal depression (Lusskin et al. 2007; Breedlove and Fryzelka 2011). It is frequently used in LMIC settings (Parsons et al. 2011; Sawyer et al. 2010; Halbreich and Karkun 2006) and in HIV-endemic communities (Chibanda et al. 2010; Manikkam and Burns 2012), and is widely used in South Africa (Hartley et al. 2011; Rotheram-Borus et al. 2011; Rochat et al. 2006). Preliminary evidence from research in North America (Kabir et al. 2008) found that the three-item anxiety subscale of a EPDS was as effective as longer versions in identifying depression risk in the postnatal period. Research in Asia (Choi et al. 2012) found that two items of the EPDS predicted antenatal risk as well as the full 10-item version. However, interpretation of these findings is limited by the fact that neither of these studies included a diagnostic measure of depression. However, recent research examining a basket of commonly used items against clinical interview methods in the United States found that a combination of two to three items worked as well in identifying depression when compared to the EPDS10 and other commonly used screening tools (O'Hara et al. 2012).

In HIV-epidemic regions of Southern Africa, the burden of antenatal and postnatal depression has been shown to be as high as 30–50 % in multiple studies (Hartley et al. 2011; Manikkam and Burns 2012; Chibanda et al. 2010; Rochat et al. 2006; Rochat et al. 2011; Stewart et al. 2010). In these resource-scarce settings, women are known to be at high risk, but given low availability of resources, they are unlikely to be screened in primary care. Research in antenatal environments in South African illustrates that universal screening is feasible and acceptable but that shorter screening tools are needed to facilitate appropriate use of scarce resources in busy PHC settings (Honikman et al. 2012). Task shifting screening to CHWs who are able to screen at routine home visits requires simple, short screening tools with good sensitivity to ensure detection of women in need of referral, but also balanced with good specificity to ensure that referrals of false positives do not overburden already overburdened PHC resources (Kagee et al. 2012). Furthermore, at PHC level, short reliable screens that help nursing professionals determine which women should be referred to a medical officer would also help in making the most use of extremely scarce resources. Yet, no studies to date using clinical interview methods have examined the effectiveness of short and ultrashort versions of the EPDS for this purpose. The aim of this research is to test the hypothesis that shortened versions of the EPDS are as effective as longer versions in identifying antenatal depression as determined by a clinical interview diagnostic method.

Methods

Data were collected at a large centralized PHC facility located in an area with high HIV prevalence, in a predominantly rural part of South Africa (Tanser et al. 2008). The facility is staffed by 20–30 nurses offering a full range of PHC services to approximately 10,000 patients per month, including antenatal outpatient clinics, with an average of 160 first time antenatal attendees per month. This facility offers a 24-h service managing normal deliveries, with between 70 and 100 deliveries monthly (Houlihan et al. 2010). The subdistrict health services include a district hospital with 250 beds and 17 decentralized PHC clinics servicing a population of 228,000 over a geographical area of approximately 1,500 km2.

The research was based on an assessment at one time point, in the second-half of pregnancy, and the details are described elsewhere (Rochat et al. 2011). Eligible women were required to attend routine antenatal care, be at least 16 years of age, and a resident in the study area. As part of Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission Programs (PMTCT), all women were screened for HIV in routine antenatal care. Women learning their HIV status for the first time during this current pregnancy were included, regardless of whether they tested HIV positive or HIV negative. HIV testing took place 2–3 weeks prior to the depression assessment (Rochat et al. 2006). Women living with HIV (WLH) prior to this pregnancy were considered a separate group, with different risk profiles, and referred to nonroutine antenatal care, and thus excluded from the study. Women with chronic health problems such as diabetes and hypertension were also referred to specialist services and excluded. Written informed consent was obtained in writing and ethical approval obtained from the Biomedical Ethics Review Board of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (E193/3) and the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee (OXTREC 014–04).

Women were interviewed in the local language (Zulu) using the major depression section of the Structured Clinical Interview for Depression (SCID) for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition) diagnoses and the EPDS administered in interview format. Anxiety was not assessed with the clinical interview method. Detailed information on cross-cultural validation and scoring methods for the presence/absence of a DSM-IV Major Depressive Episode (MDE) are available (Rochat et al. 2011). The highest recommended cutoff of ≥13 was used to define probable depression on the EPDS. HIV status was collected via self-report and verified against clinic records.

Data were double entered for accuracy into Stata 11. Data analysis examined the sensitivity and specificity and the positive predictive value (PPV) of the EPDS against the depression outcome, determined by the SCID. Multiple regression techniques examined EPDS items to identify those items significantly associated with clinical depression, significance was set at p < 0.001. Previously published scoring techniques for using shorter versions of the EPDS were applied (Mitchell and Coyne 2007; Kabir et al. 2008; Choi et al. 2012). The same recommended EPDS cutoff ≥13 was used for all versions of the scale. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis examined four versions of the EPDS including the full 10-item EPDS (EPDS10), the traditional depression subscale (EPDS7), and the new five-item (EPDS5R) and three-item versions (EPDS-3R) identified through item regression analysis. Given that anxiety was not measured using a gold standard measure, the three-item anxiety subscale was not examined in this analysis. Effectiveness was determined by the ability of versions or subscales to predict accurately the presence (sensitivity) or absence (specificity) of depression according to the “gold standard” clinical diagnostic measure. Various statistics were examined and included both positive and negative predictive values in order to take prevalence into account, and to fully explore the data, likelihood ratios were calculated conventionally and weighted by prevalence. Kappa statistic and Cronbach's alpha were calculated for each version.

Results

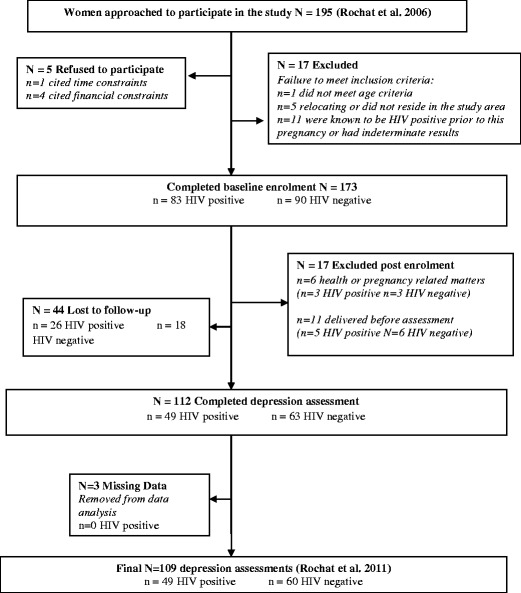

Figure 1 outlines the sample recruitment as published elsewhere (Rochat et al. 2011). A total of 112 women (72 %) completed the depression assessment and comprised the sample for this analysis. While more HIV-positive women were lost to follow up, baseline data showed no significant distinguishing characteristics between women lost to follow-up and those interviewed.

Fig. 1.

Sample recruitment (Rochat et al. 2011)

Sociodemographic characteristics (Table 1) are similar to those reported in the larger baseline cohort (Rochat et al. 2006). Most women were young, had completed some or all of their secondary education, were from low-income groups, were unmarried but in a stable relationship with the father of the child, and living with their families rather than cohabiting with partners. The majority (85.3 %) had unplanned pregnancies, and 49/109 (45 %) women were newly diagnosed with HIV during this pregnancy.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristics of participants | N (109) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Median | 24 | |

| Range | 16–40 | |

| Education | ||

| No education | 14 | 12.8 % |

| Completed primary education | 38 | 34.9 % |

| Some secondary education | 32 | 29.4 % |

| Completed secondary | 25 | 22.9 % |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 100 | 91.7 % |

| Married | 9 | 8.3 % |

| In stable relationship with partner | ||

| Yes | 98 | 89.9 % |

| No | 7 | 6.4 % |

| Missing | 4 | 3.7 % |

| Cohabiting with father | ||

| Yes | 21 | 19.2 % |

| No | 60 | 55.1 % |

| Missing | 28 | 25.7 % |

| Number of children with father | ||

| First child | 57 | 52.3 % |

| At least one other | 52 | 47.7 % |

| Living arrangements | ||

| Family | 87 | 79.8 % |

| Nonfamily | 17 | 15.6 % |

| Missing | 5 | 4.6 % |

| Regular income | ||

| Yes | 54 | 49.5 % |

| No | 55 | 50.5 % |

| Grant assistance | ||

| Child support grant | 52 | 47.7 % |

| Care dependency grant | 1 | 0.9 % |

| No grant | 55 | 50.5 % |

| Missing | 1 | 0.9 % |

The prevalence of depression was high, with similar rates found on the SCID (47 % CI 37.2–56.3) and the EPDS10 (44 % CI 34.57–53.50). Close to a third (14/51, 28 %) of depressed women reported episode duration of between 2 weeks and 2 months, while two thirds (24/51, 66 %) reported episode duration greater than 2 months, and only a few women reported duration as greater than 6 months. Less than a quarter (8/51 or 16 %) of depressed women reported a previous episode that had resolved prior to the pregnancy, and two out of eight reported that a previous episode had occurred in the postnatal period of a previous pregnancy. Slightly more HIV-positive women (n = 27) were depressed than HIV-negative women (n = 24). Depression and HIV status were not significantly associated [OR 1.84 (0.86–3.95), p = 0.117].

Regression analysis of items on the EPDS10 against the depression outcome (Table 2) showed five significant items in univariate analysis, and these included: items 2, 7, 8, 9, and 10. These items constituted the novel five-item version of the EPDS (EPDS5R) examined in ROC analysis. When these five items were entered into multivariable analysis, three items remained significant: items 2, 9, and 10. These three items constituted the novel three-item version (EPDS3R) examined in ROC analysis. We termed the five-item version, the short version and the three-item version, the ultrashort version, based on previous suggestions (Mitchell and Coyne 2007).

Table 2.

EPDS items, standard and revised versions, and univariate and multivariate statistics by item

| EPDS10 items | Subscale | Univariate OR (95 % CI) p | Short | Multivariate OR (95 % CI) p | Ultrashort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Able to laugh and see the funny side of things | EPDS7 | 1.59 (1.04–2.41) | 0.029 | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Looked forward with enjoyment to things | EPDS7 | 2.32 (1.50–3.60) | <0.001* | EPDS5R | 1.79 (1.08–2.98) | 0.024** | EPDS3R |

| 3. Blamed myself unnecessarily for things | EPDS3 | 1.3 (0.90–1.92) | 0.152 | – | – | – | – |

| 4. Anxious and worried for no good reason | EPDS3 | 0.64 (0.42–0.97) | 0.035 | – | – | – | – |

| 5. Scared and panicky for no good reason | EPDS3 | 1.62 (1.08–2.42) | 0.019 | – | – | – | – |

| 6. Things are getting on top of me | EPDS7 | 1.06 (0.74–1.51) | 0.733 | – | – | – | – |

| 7. So unhappy I have had difficulty sleeping | EPDS7 | 2.14 (1.4–3.27) | <0.001* | EPDS5R | 1.07 (0.59–1.94) | 0.812 | – |

| 8. I have felt sad or miserable | EPDS7 | 2.42 (1.59–3.70) | <0.001* | EPDS5R | 1.46 (0.85–2.52) | 0.166 | – |

| 9. So unhappy I have been crying | EPDS7 | 4.04 (2.29–7.12) | <0.001* | EPDS5R | 2.31 (1.19–4.51) | 0.013** | EPDS3R |

| 10. Thought of harming myself has occurred to me | EPDS7 | 3.07 (1.73–5.44) | <0.001* | EPDS5R | 1.86 (0.99–3.46) | 0.050** | EPDS3R |

*significance p=0.001

** significance p=0.050

Table 3 details the performance of each of the four versions of the EPDS examined in data analysis, including PPVs, likelihood ratios, kappa, and Cronbach's alpha statistics. The EPDS10 showed sensitivity of 69 % and specificity of 78 %. An optimal cutoff ≥13 yielded the highest percentage of correctly classified cases (73.3 %). Cronbach's alpha for the EPDS10 was fair (ά = 0.6130) but fell short of general guidelines for a stand-alone screening measure (ά ≥ 0.70). The performance of the EPDS7 depression subscale was better than the full 10-item scale with high PPV (83.78), improved reliability (α 0.7033), and a moderate kappa statistic (k 0.5129).

Table 3.

Diagnostic validity of standard, short, and ultrashort versions of the EPDS for the clinical interview depression outcome

| Version | ROC area (95 % CI) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | LR + [C] | LR + [W] | LR − [C] | LR − [W] | Correctly classified (%) | k | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPDS10 | 0.8169 (0.73–0.89) | 68.63 | 77.59 | 72.92 | 73.77 | 3.061 | 2.692 | 0.404 | 0.355 | 73.39 | 0.4638 | 0.6130 |

| EPDS7 | 0.8323 (0.75–0.90) | 60.78 | 89.66 | 83.78 | 72.22 | 5.875 | 5.166 | 0.437 | 0.384 | 76.15 | 0.5129 | 0.7033 |

| EPDS5R | 0.8440 (0.77–0.91) | 64.71 | 86.22 | 80.49 | 73.53 | 4.691 | 4.125 | 0.409 | 0.360 | 76.15 | 0.5152 | 0.7501 |

| EPDS3R | 0.8396 (0.76–0.91) | 60.78 | 89.66 | 83.78 | 72.22 | 5.875 | 5.166 | 0.437 | 0.384 | 73.39 | 0.5129 | 0.6092 |

All versions based on the standard EPDS cutoff of ≥13

ROC area area under the receiving operating characteristic, PPV positive predictive value, NPV negative predictive value, LR [C] conventional, LR [W] weighted by prevalence, k kappa statistic: moderate agreement (0.40–0.60), α Cronbach's alpha: stand-alone ≥0.75 cautious/acceptable 0.65–0.75, EPDS5R short version of the EPDS including items 2, 7, 8, 9, and 10, EPDS3R ultrashort version of the EPDS including items 2, 9, and 10

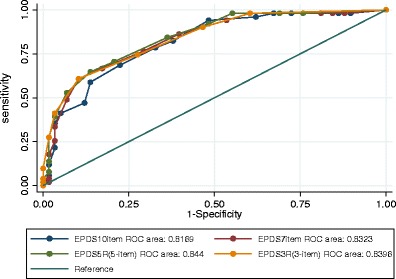

The novel five-item version (EPDS5R) that included five items from the seven-item depression subscale showed the best ROC statistic (AUC 0.8440) and alpha statistic (ά = 0.7501) meeting the minimum guideline for a stand-alone tool. The ultrashort three-item version (EPDS3R), which included only three items of the seven-item subscale, had a high PPV (83.78) but was less reliable as a stand-alone tool (α = 0.6092); however, this may be an artifact of the small number of items included.

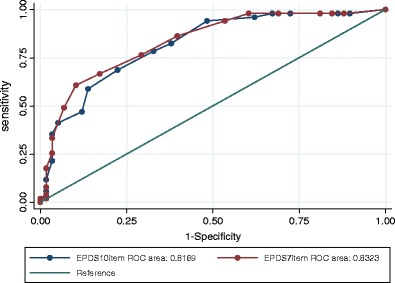

The ROC graph (Fig. 2) shows the performance of the full 10-item EPDS and the standard seven-item depression sub-scale. The seven-item depression subscale EPDS7 (AUC = 0.8323) performed slightly better than the full EPDS10 (AUC = 0.8169). In Fig. 3, the performance of the 10-item, seven-item, and new short (EPDS5R) and ultrashort (EPDS3R) versions are illustrated. The novel five-item (EPDS5R AUC = 0.844) and the three-item (EPDS-3R AUC = 0.8396) versions' performance improves slightly on the performance of the EPDS7 and substantially on the performance of the EPDS10, despite requiring less items.

Fig. 2.

ROC curve for EPDS10 (full item version) and EPDS7 (depression subscale)

Fig. 3.

ROC curve including EPDS10, EPDS7, and short EPDS5R and ultrashort EPDS3R

Discussion

The performance of the short EPDSR5 and ultrashort EPDSR3 version supports evidence that shorter versions of the EPDS may be effective in detecting antenatal depression. This research raises new considerations for screening research in LMIC heavily affected by HIV. These include considerations related to the performance and validation of screening methods against clinical interviews, the importance of screening for high risk women, the potential of suicide ideation items in screening for risk in the antenatal period, and the feasibility and acceptability of using short and ultrashort tools in PHC in LMIC.

Rates of depression on the screening measure versus the clinical diagnostic interview

Firstly, in this research, we found that the rate of depression was higher on the clinical interview method than on the EPDS screening measure, a finding that is becoming more common in LMIC settings (Parsons et al. 2011) and warrants attention in discussions about screening and treatment in these settings (O'Hara et al. 2012). There is an almost complete absence of studies that include a clinical diagnostic measure from LMICs. More research studies are needed that include both screening and diagnostic tools. A better understanding of the ability of screening measures to detect risk in these settings may prove a more fruitful research agenda in Southern Africa and other LMIC, compared to research using only screening measures that assume similar test performances as seen in international contexts.

Screening for antenatal depression among high risk women in LMIC

The sociodemographic profile of the study women illustrates that these are high risk women, the majority of whom are low income, have unplanned pregnancies, and a high proportion of whom have been diagnosed HIV positive during the current pregnancy. This is an important finding because while low rates of detection are frequently reported in all settings, evidence suggests that low-income women are particularly likely to go undetected and are less likely to access mental health care (Kopelman et al. 2008). However, it is also important to consider that these particularly elevated risk situations may have influenced reporting of symptoms and the rates and severity of depression. Research is needed to replicate these findings among women from lower risk groups, given that high levels of chronic environmental risk and a sense of hopelessness may influence not only the onset and duration of depression but also the symptoms reported. An important point of similarity between this and other research (O'Hara et al. 2012; Dickens et al. 2012; Milgrom et al. 2008; Zelkowitz et al. 2008; Matthey et al. 2012) is that we found a relationship between the role of the EPDS depressive items (items 2, 8, and 9) and a chronic presentation of depression. In this study, two thirds of the women diagnosed with depression had episode duration greater than 2 months, suggesting a predominantly chronic presentation that may have influenced which EPDS items improved detection. Further research is required to elucidate the differences in acute and chronic presentations of depression across pregnancy and in the postnatal period, and to determine the role of a previous history of depression prior to the pregnancy more clearly.

The role of suicide ideation in screening for antenatal depression

Lastly, it is noteworthy that two of the three items found to be highly effective in predicting depression in this research, item 2 (loss of interest) and item 9 (mood), are similar to the two items included in the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) screen that is increasingly recommended and shown to be effective in primary care (Smith et al. 2010). The third item, suicidal ideation (item 10) is rarely used in settings where resources to respond are limited (Dickens et al. 2012). Nonetheless, a recent review (Lindahl et al. 2005) found that pregnancy did not offer a protective effect for suicide ideation, with between 5 and 14 % of women reporting suicide ideation during pregnancy or the postnatal period. There is growing evidence of suicide ideation risk during pregnancy in LMIC (Asad et al. 2010; Breedlove and Fryzelka 2011; Choi et al. 2012) and high numbers of women in this research were suicidal, as reported elsewhere (Rochat et al. 2013). While suicide ideation and attempts are found to be lower during pregnancy and postpartum than in the general population of women, when deaths do occur, suicides account for up to 20 % of postpartum deaths (Oates 2003). Thus, given that this item has high predictive value for depression, its inclusion as a core item in a screening instrument seems highly appropriate.

The application of short and ultrashort versions of the EPDS in antenatal screening in LMIC

The potential of short and ultrashort screening tools for LMIC settings is apparent in two important health care service contexts: at the community level for screening by home visitors and CHWs, and at the PHC level for screening by nurses and other health care professionals and within prevention of mother to child transmission programming in geographical areas heavily affected by HIV. The use of the three- and five-item versions of the EPDS may have particular useability in ensuring that all opportunities for regular and repeated screening are maximized in low-resourced settings.

Community-level screening with the ultrashort EPDS3R

There are increasing calls for community-level human resources to be engaged in delivering PHC in resource-limited settings, under the supervision of nurse practitioners and midwives (Patel and Kirkwood 2008). Given that shorter tools increase the feasibility and acceptable of screening for both lay professionals and women alike, an ultrashort three-item screen could prove highly suitable for routine screening for depression during home visits by CHWs. The brevity, sensitivity, and user friendliness of this version makes it suited to first-level screening, since it is unlikely to overburden CHWs or to miss women in need of further screening and referrals to higher level services. Routine use of the ultrashort three-item version by CHW trained to offer psychoeducation and support could ensure that women identified as being at risk for depression are referred to a professional nurse for further assessment through antenatal services. This may also improve opportunities for contact with health care among depressed women given the evidence that the presence of antenatal depression can impact on uptake of antenatal care and engagement with health services.

Primary health care-level screening with the short EPDS5R

A concern in all LMIC is that a significant portion of antenatal care is delivered by PHC nurses, themselves considered a scarce and overburdened resource. This raises a different set of challenges at the PHC clinic level, where a lack of nurse resources and time constraints may degrade opportunities for routine mental health screening or intervention, regardless of community-level referral systems, and where the cost of treatment of false positives may make treatment unsustainable. While shorter tools may be key to making screening more acceptable and feasible for CHWs, at the level of nursing care, screening tool specificity and reliability also play an important role in ensuring that scare resources are adequately expended (Kagee et al. 2012).

The slightly longer five-item version (EPDS5R) that has significantly improved reliability over the EPDS10 may have particular usability for nurse screening given that it is still short, performs well as a stand-alone assessment of depression, and has improved specificity over the three-item version. By using the EPDS5R as a tool to further screen women referred by CHWs, the health system would benefit from a filtering system that reduces the number of false positives ensuring that women who require higher level screening by medical doctors or psychologists are flagged and referred. This increased specificity occurs in a context where the nurse professional is also trained and able to make clinical judgments about the women's needs for care.

Barriers and challenges to universal screening at home and in clinics in LMIC

The usefulness of short and ultrashort screens aside, challenges still exist, for example, it is not clear whether increased detection and referral at a community level or the availability of shorter more reliable screening tools, would necessarily increase nurse responsiveness to community referrals or improve treatment access or cost effectiveness (Hewitt and Gilbody 2009). Several barriers, beyond detection, may play a role in lowered access and uptake of treatment by depressed women including: financial costs, lack of insurance, lack of transportation, long waiting periods for treatment, previous bad experiences with mental health services and concerns of stigma, reduced autonomy, and loss of maternal rights (Kopelman et al. 2008; Rochat et al. 2006; Paulden et al. 2009). These issues are important as, in some instances, universal screening has not been effective in improving outcomes (Miller et al. 2009) and where it has, the availability of treatment options alongside universal screening has been an important contributor to success. As such, the challenges to integration and delivery of mental health care in resource-poor settings are complex and not limited to the provision of short screening tools.

An equally important priority would be to establish and adapt appropriate community-level interventions (Patel et al. 2010) making use of community human resources to increase access to treatment and to evaluate user-friendly treatment and referral algorithms such as those recently published by the World Health Organization (World Health Organization 2010).

This study had a number of limitations including: the relatively small sample size, the possibility of selection bias, and the high prevalence of HIV in the sample that may have influenced the prevalence and severity of depression, although given the high rates of HIV among urban and rural women in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa (Karim et al. 2011), studies in such communities are important (Shao and Williamson 2012). These limitations raise questions about the generalizability of these findings especially in low-risk samples. Clearly, replication and further research is urgently required. A major strength of the study is the use of a gold standard clinical diagnostic measure of depression in an under-researched population, in a LMIC. To date, the vast majority of this kind of research has been undertaken in high-income settings. There is increasing evidence of the detrimental role anxiety may play in pregnancy and the importance of screening for anxiety (Matthey et al. 2012; Meades and Ayers 2011); however, this study did not include a clinical measure of anxiety and, hence, the performance of the three-item anxiety subscale of the EPDS to detect antenatal anxiety could not be examined, and future research should examine both antenatal depression and anxiety.

Conclusions

The failure to adequately detect antenatal depression has wide-reaching consequences. Most importantly, it results in the loss of opportunities to prevent postnatal depression that, in turn, is known to result in ongoing difficulties for the mother, negative effects on the children, lowered access to quality antenatal and postnatal care, and higher health care costs (Alder et al. 2007; Oates 2003), regardless of the setting. While preliminary, these results offer support for new, innovative, and feasible approaches to detection of depression in pregnancy that may be well suited to resource-poor settings. However, further research is urgently required to test short screening tools against clinical diagnostic instruments in larger samples.

Acknowledgments

We thank the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health for permission to conduct this research. This study was funded by grants from University of Oxford (HQ5035), the Tuixen Foundation (9940), and the Wellcome Trust (082384/Z/07/Z and 071571). The first author receives salary support from the Wellcome Trust; data analysis was supported through a grant from the American Psychological Foundation. We acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Frank Tanser regarding statistics.

Contributor Information

Tamsen J. Rochat, Phone: +27-035-5507500, FAX: +27-035-5507565, Email: trochat@africacentre.ac.za

Mark Tomlinson, Email: markt@sun.ac.za.

Marie -Louise Newell, Email: mnewell@africacentre.ac.za.

Alan Stein, Email: alan.stein@psych.ox.ac.uk.

References

- Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, Hosli I, Holzgreve W. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: a risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20(3):189–209. doi: 10.1080/14767050701209560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asad N, Karmaliani R, Sullaiman N, Bann CM, McClure EM, Pasha O, Wright LL, Goldenberg RL. Prevalence of suicidal thoughts and attempts among pregnant Pakistani women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(12):1545–1551. doi: 10.3109/00016349.2010.526185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin MP. Antenatal screening and early intervention for “perinatal” distress, depression and anxiety: where to from here? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breedlove G, Fryzelka D. Depression screening during pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56(1):18–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2010.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibanda D, Mangezi W, Tshimanga M, Woelk G, Rusakaniko S, Stranix-Chibanda L, Midzi S, Shetty AK. Postnatal depression by HIV status among women in Zimbabwe. J Womens Health. 2010;19(11):2071–2077. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SK, Kim JJ, Park YG, Ko HS, Park IY, Shin JC. The Simplified Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for antenatal depression: is it a valid measure for pre-screening? Int J Med Sci. 2012;9(1):40. doi: 10.7150/ijms.9.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health: Task Force on Mental Health The future of pediatrics: mental health competencies for pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):410–421. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens A, Joska J, Obuku EA, Amos T, Musisi S, Stein DJ. Comparing the accuracy of brief versus long depression screening instruments which have been validated in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:187. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowswell T, Guillermo C, Duley L, Gates S, Gülmezoglu AM, Khan-Neelofur D, Piaggio GP (2010) Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Issue 10. Art. No.: CD000934). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000934.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Earls MF, The Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child Family Health Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1032–1039. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Mello MC, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, Holmes W (2012) Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low-and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90 (2):139–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gjerdingen DK, Yawn BP. Postpartum depression screening: importance, methods, barriers, and recommendations for practice. J AM Board Fam Med. 2007;20(3):280–288. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.03.060171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JH, Tyer-Viola L (2010) Detection, treatment, and referral of perinatal depression and anxiety by obstetrical providers. J Womens Health 19 (3):477–490. doi:doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.1352 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):1012. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbreich U, Karkun S. Cross-cultural and social diversity of prevalence of postpartum depression and depressive symptoms. J Affect Disorders. 2006;91(2–3):97–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley M, Tomlinson M, Greco E, Comulada WS, Stewart J, le Roux I, Mbewu N, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Depressed mood in pregnancy: prevalence and correlates in two Cape Town peri-urban settlements. Reprod Health. 2011;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt CE, Gilbody SM. Is it clinically and cost effective to screen for postnatal depression: a systematic review of controlled clinical trials and economic evidence. BJOG. 2009;116(8):1019–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honikman S, van Heyningen T, Field S, Baron E, Tomlinson M. Stepped care for maternal mental health: a case study of the Perinatal Mental Health Project in South Africa. PLoS Med. 2012;9(5):e1001222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan CF, Bland RM, Mutevedzi PC, Lessells RJ, Ndirangu J, Thulare H, Newell ML (2010) Cohort profile: Hlabisa HIV Treatment and Care Programme. Int J Epidemiol. doi:10.1093/ije/dyp402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kabir K, Sheeder J, Kelly LS. Identifying postpartum depression: are 3 questions as good as 10? Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):e696–702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagee A, Tsai AC, Lund C, Tomlinson M (2012) Screening for common mental disorders in low resource settings: reasons for caution and a way forward. Inter Health 5:11–14. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihs004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kapetanovic S, Christensen S, Karim R, Lin F, Mack WJ, Operskalski E, Frederick T, Spencer LS, Stek A, Kramer F. Correlates of perinatal depression in HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(2):101–108. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim QA, Kharsany AB, Frohlich JA, Werner L, Mashego M, Mlotshwa M, Madlala BT, Ntombela F, Karim SSA. Stabilizing HIV prevalence masks high HIV incidence rates amongst rural and urban women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(4):922–930. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Gordon TEJ, La Porte LM, Adams M, Kuendig JM, Silver RK. The utility of maternal depression screening in the third trimester. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(5):509.e501–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelman RC, Moel J, Mertens C, Stuart S, Arndt S, O'Hara MW. Barriers to care for antenatal depression. Psych Serv. 2008;59(4):429–432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.4.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchn BM. Depression guideline highlights choices, care for hard-to-treat or pregnant patients. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2465–2466. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster CA, Gold KJ, Flynn HA, Yoo H, Marcus SM, Davis MM. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine AB, Aaron EZ, Criniti SM. Screening for depression in pregnant women with HIV infection. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(5):352–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K, Bosch-Capblanch X, Van Wyk BE, Odgaard-Jensen J, Johansen M, Aja GN, Zwarenstein M (2010) Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusskin SI, Pundiak TM, Habib SM. Perinatal depression: hiding in plain sight. Can J Psychiat. 2007;52(8):479–488. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthey S, Fisher J, Rowe H (2012) Using the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale to screen for anxiety disorders: conceptual and methodological considerations. J Affect Disorders Online first. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Manikkam L, Burns JK (2012) Antenatal depression and its risk factors: An urban prevalence study in KwaZulu-Natal. South African Medical Journal 102 (12):940–944 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Meades R, Ayers S. Anxiety measures validated in perinatal populations: a systematic review. J of Affect Disorders. 2011;133:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, Bilszta JL, Hayes B, Barnett B, Brooks J, Ericksen J, Ellwood D, Buist A. Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: a large prospective study. J Affect Disorders. 2008;108(1):147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom J, Mendelsohn J, Gemmill AW. Does postnatal depression screening work? Throwing out the bathwater, keeping the baby. J Affect Disorders. 2011;132(3):301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Shade M, Vasireddy V. Beyond screening: assessment of perinatal depression in a perinatal care setting. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12(5):329–334. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Coyne J. Screening for postnatal depression: barriers to success. BJOG. 2009;116(1):11–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Coyne JC (2007) Do ultra-short screening instruments accurately detect depression in primary care?: a pooled analysis and meta-analysis of 22 studies. Br J Gen Pract 57 (535):144151. doi:Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2034175/pdf/bjpg57-144.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- O'Hara MW, Stuart S, Watson D, Dietz PM, Farr SL, D'Angelo D. Brief scales to detect postpartum depression and anxiety symptoms. J Womens Health. 2012;21(12):1237–1243. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates M. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Brit Med Bull. 2003;67(1):219–229. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons CE, Young KS, Rochat T, Kringelbach ML, Stein A (2011) Postnatal depression and its effects on child development: a review of evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Brit Med Bull Online first, November 29:2012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Patel V, Kirkwood B. Perinatal depression treated by community health workers. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):868–869. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Simon G, Chowdhary N, Kaaya S, Araya R. Packages of care for depression in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(10):e1000159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, Naik S, Pednekar S, Chatterjee S, De Silva MJ, Bhat B, Araya R, King M, Simon G, Verdeli H, Kirkwood BR. Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9758):2086–2095. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61508-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulden M, Palmer S, Hewitt C, Gilbody S. Screening for postnatal depression in primary care: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b5203. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psaros C, Geller PA, Aaron E. The importance of identifying and treating depression in HIV infected, pregnant women: a review. J Psychosom Obst Gyn. 2009;30(4):275–281. doi: 10.3109/01674820903254740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A. Maternal depression and child health: the need for holistic health policies in developing countries. Harv Health Pol Rev. 2005;6:70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Creed F. Outcome of prenatal depression and risk factors associated with persistence in the first postnatal year: prospective study from Rawalpindi, Pakistan. J Aff Disorders. 2007;100(1–3):115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, Roberts C, Creed F. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):902–909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61400-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice BD, Batzing-Feigenbaum J, Hosegood V, Tanser F, Hill C, Barnighausen T, Herbst K, Welz T, Newell ML. Population and antenatal-based HIV prevalence estimates in a high contracepting female population in rural South Africa. BMC Pub Health. 2007;7:160. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat TJ, Bland RM, Tomlinson M, Stein A. Suicide ideation, depression and HIV among pregnant women in rural South Africa. Health. 2013;5(3A):650–661. doi: 10.4236/health.2013.53A086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat TJ, Richter LM, Doll HA, Buthelezi NP, Tomkins A, Stein A. Depression among pregnant rural South African women undergoing HIV testing. JAMA. 2006;295(12):1376–1378. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochat TJ, Tomlinson M, Barnighausen T, Newell ML, Stein A. The prevelance and clinical presentation of antenatal depression in rural South Africa. J Affect Disorders. 2011;135(1):362–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Richter L, Van Rooyen H, van Heerden A, Tomlinson M, Stein A, Rochat T, de Kadt J, Mtungwa N, Mkhize L, Ndlovu L, Ntombela L, Comulada WS, Desmond KA, Greco E. Project Masihambisane: a cluster randomised controlled trial with peer mentors to improve outcomes for pregnant mothers living with HIV. Trials. 2011;12:2. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LH, Cook JA, Grey DD, Weber K, Wells C, Golub ET, Wright RL, Schwartz RM, Goparaju L, Cohan D. Perinatal depressive symptoms in HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected women: a prospective study from preconception to postpartum. J Womens Health. 2011;20(9):1287–1295. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H. Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in Africa: a systematic review. J Affect Disorders. 2010;123(1–3):17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selke HM, Kimaiyo S, Sidle JE, Vedanthan R, Tierney WM, Shen C, Denski CD, Katschke AR, Wools-Kaloustian K. Task-shifting of antiretroviral delivery from health care workers to persons living with HIV/AIDS: clinical outcomes of a community-based program in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(4):483–490. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181eb5edb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, Williamson C (2012) The HIV-1 epidemic: low-to middle-income countries. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2 (3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Smith MV, Gotman N, Lin H, Yonkers KA. Do the PHQ-8 and the PHQ-2 accurately screen for depressive disorders in a sample of pregnant women? Gen Hosp Psychiat. 2010;32(5):544–548. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart R, Bunn J, Vokhiwa M, Umar E, Kauye F, Fitzgerald M, Tomenson B, Rahman A, Creed F. Common mental disorder and associated factors amongst women with young infants in rural Malawi. Soc Psych Psych Epid. 2010;45(5):551–559. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanser F, Hosegood V, Barnighausen T, Herbst K, Nyirenda M, Muhwava W, Newell C, Viljoen J, Mutevedzi T, Newell ML. Cohort profile: Africa Centre Demographic Information System (ACDIS) and population-based HIV survey. Int J Epi. 2008;37(5):956–962. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2008;65(7):805–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2000) Preventing suicide: a resource for teachers and other school staff. Mental and Behavioural Disorders, World Health Organisation, Geneva. doi:http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/62.pdf

- World Health Organization (2010) Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings. www.who.int/mental_health/evidnce/mhGAP Accessed 12 December, 2010. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (2011) Progress report 2011: global HIV/AIDS response.

- Yonkers KA, Smith MV, Lin H, Howell HB, Shao L, Rosenheck RA. Depression screening of perinatal women: an evaluation of the healthy start depression initiative. Psych Serv. 2009;60(3):322. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelkowitz P, Saucier J-F, Wang T, Katofsky L, Valenzuela M, Westreich R. Stability and change in depressive symptoms from pregnancy to two months postpartum in childbearing immigrant women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0219-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]