Abstract

Background: Epidemiologic studies have yielded inconsistent findings between breastfeeding and epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) risk.

Objective: We performed a meta-analysis to summarize available evidence of the association between breastfeeding and breastfeeding duration and EOC risk from published cohort and case-control studies.

Design: Relevant published studies were identified by a search of MEDLINE through December 2012. Two authors (T-TG and Q-JW) independently performed the eligibility evaluation and data abstraction. Study-specific RRs from individual studies were pooled by using a random-effects model, and heterogeneity and publication-bias analyses were conducted.

Results: Five prospective and 30 case-control studies were included in this analysis. The pooled RR for ever compared with never breastfeeding was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.69, 0.83), with moderate heterogeneity (Q = 69.4, P < 0.001, I2 = 55.3%). Risk of EOC decreased by 8% for every 5-mo increase in the duration of breastfeeding (RR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.90, 0.95). The risk reduction was similar for borderline and invasive EOC and was consistent within case-control and cohort studies.

Conclusions: Results of this meta-analysis support the hypothesis that ever breastfeeding and a longer duration of breastfeeding are associated with lower risks of EOC. Additional research is warranted to focus on the association with cancer grade and histologic subtypes of EOC.

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the second most-common cause of gynecologic cancer mortality worldwide, which accounted for almost 4.2% of all female cancer deaths in 2008 (1). Because EOC is often diagnosed at an advanced stage, has a poor prognosis with an overall 5-y survival rate of just 45% (2), and early detection efforts have not yet been successful (3), the identification of modifiable risk factors is necessary to reduce the burden of disease (4).

Two well-established risk factors for EOC [ie, the use of oral contraceptives (OCs) and parity] have been hypothesized to decrease risk by suppressing ovulation, which has been explained by the ‘‘incessant ovulation’’ hypothesis (5) or related to decreasing gonadotropin concentrations (6–8). Our recent meta-analysis (9) supported this hypothesis because later menarcheal age was inversely associated with EOC risk. Breastfeeding also causes gonadotrophin suppression. This suppression leads to low estrogen concentrations and anovulation with a resulting period of lactational amenorrhea and, therefore, has been investigated as a potential factor related to EOC development (10).

A report from the World Cancer Research Fund identified breastfeeding as “limited suggestive” for protection from EOC (11). Although a collaborative pooled analysis of 12 case-control studies in North America showed an inverse relation between ever breastfeeding and EOC risk (7), several prospective cohort studies have shown no association (12, 13). Analyses by histologic subtypes also showed conflicting results (14–16). Moreover, findings on the protective role of a longer duration of breastfeeding have been still inconsistent in recent studies (4, 14, 16, 17). A previous meta-analysis that included 15 case-control studies from developed countries published through 2005 was done by Ip et al (18) and was published in 2009, which showed a significant inverse association between ever breastfeeding and EOC risk. Since this meta-analysis, several relevant studies, including prospectively designed studies on the association between breastfeeding and EOC risk, have been published. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis of all observational studies published up to December 2012 to summarize available evidence on the association between both ever breastfeeding and breastfeeding duration with risk of EOC.

METHODS

Literature search

We performed a comprehensively literature search including published studies from database initiation until December 31, 2012 with the use of MEDLINE (PubMed; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed). The search was limited to published studies in English and studies of humans by using the following search key words and Medical Subject Headings terms: (breastfeeding OR breast feed OR lactation OR infant nutrition OR breast milk OR milk human) AND (ovary OR ovarian) AND (cancer OR neoplasm OR carcinoma OR tumor). We also reviewed references of all included studies for additional publications. We followed standard criteria for conducting and reporting meta-analyses (19, 20).

Study selection

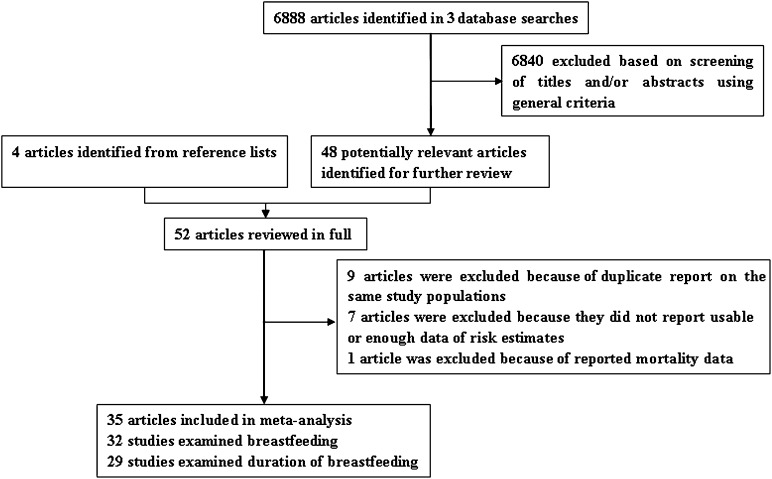

To be included, studies had to use a case-control or cohort study design and investigate the association between ever breastfeeding or the total duration of breastfeeding and incident EOC. The publication had to present the HR, OR, or RR with 95% CIs or data necessary to calculate these. When multiple publications from the same study were available, we used the publication with the largest number of cases and most-applicable information. We identified 35 potentially relevant full-text publications (4, 12–17, 21–45) from 6892 articles (Figure 1). Four publications (46–49) only reported the longest compared with shortest categories of total duration of breastfeeding and were, therefore, only included in the breastfeeding duration and dose-response analysis. For the cancer histology subgroup analysis, we included 2 publications (50, 51) that were duplicate reports from an already-represented study population but reported information on EOC histology.

FIGURE 1.

Selection of studies for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Data abstraction

For each eligible study, 2 investigators (T-TG and Q-JW) independently performed the eligibility evaluation and data abstraction. Disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus. Data abstracted from each study were as follows: author list, year of publication, study region and design, study sample size (number of cases and controls or cohort size), range of follow-up for cohort studies, exposure and outcome assessment including ever breastfeeding and the total or average breastfeeding-duration categories, study-specific adjusted estimates with their 95% CIs for ever compared with never breastfeeding and longest compared with shortest of the total or average duration category of breastfeeding, and factors matched by or adjusted for in the design or data analysis. If multiple estimates of the association were available, we abstracted the estimate that adjusted for the most covariates. If no adjusted estimates were presented, we included the crude estimate. If no estimate was presented in a given study, we calculated it and its 95% CI according to the raw data presented in the article.

We did not use the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (9, 52, 53) to assess the methodologic quality of all included studies because quality scoring in a meta-analysis of observational studies is controversial, lacks demonstrated validity, and sometimes results may not be associated with quality (54, 55). Instead, we carried out numerous subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

Statistical analysis

Study-specific adjusted RRs were used as measures of the association across studies. Because absolute risk of EOC is low, we assumed that estimates of ORs from case-control studies and risk, rate, or HRs from cohort studies were all valid estimates of the RR, and therefore, we reported all results as the RR for simplicity (9). For studies that did not use the category with the shortest-duration breastfeeding as the reference, we used the effective-count method proposed by Hamling et al (56) to recalculate RRs.

For the dose-response analysis, we used the method proposed by Greenland et al (57) and Orsini et al (58) to compute study-specific slopes (linear trends) and 95% CIs from the ln of RRs and CIs across categories of the total duration of breastfeeding. The method requires that the distribution of cases and person-years of noncases and RRs with the variance estimates for ≥3 quantitative exposure categories are known. For studies that reported the duration by ranges, we estimated the midpoint in each category by calculating the average of the lower and upper bounds. When the highest category did not have an upper bound, we assumed the length of the open-ended interval to be the same as that of the adjacent interval. When the lowest category did not have a lower bound, we set the lower bound to zero. Dose-response results in forest plots are presented on the basis of 5-mo increments for the total duration of breastfeeding.

We evaluated the heterogeneity of RRs across studies by using the Cochrane Q statistic, where P < 0.1 was indicative of statistically significant heterogeneity, and I2 statistic. The summary estimate was based on the fixed-effects model (59) for no detected heterogeneity or the random-effects model (60) when substantial heterogeneity was detected. In both methods, the weight of each study depended on the inverse of the variance of log OR, which was estimated by the 95% CI from each study. Because limited studies (14, 16, 17, 23, 25, 30, 36, 39, 46) reported results of the average duration of breastfeeding per child, summary estimates were calculated for ever breastfeeding and the total duration of breastfeeding. Subgroup analyses were carried out based on the study design (cohort compared with case-control studies), type of controls within case-control studies (population-based compared with hospital-based controls), exposure assessment (self-administered questionnaire compared with trained interviewers), geographic location (Europe, America, and Asia), cancer grading (invasive compared with borderline), and cancer histotype (serous, mucinous, endometrioid, and clear cell). We also stratified the meta-analysis by potentially important confounders (ie, parity, BMI, OC use, and smoking status). Heterogeneity between subgroups was evaluated by using a meta-regression. Finally, we carried out sensitivity analyses by excluding one study at a time to explore whether results were strongly influenced by a specific study.

Publication bias was evaluated via Egger's linear regression (61), Begg's rank-correlation methods (62), and funnel plots. P < 0.05 for Egger's or Begg's tests was considered representative of a significant statistical publication bias. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata software (version 11.2; StataCorp). P values were 2 sided with a significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 35 included articles are shown in Table 1. The included articles, which represented 14,465 cases and 706,152 noncases, were published between 1983 and 2012 and consist of 5 cohort studies (4, 12, 13, 21, 22) and 30 case-control studies (14–17, 23–45, 47–49). All of the studies only included parous women in analyses. Of the 5 cohort studies, 2 studies each were conducted in the United States (4, 13) and Europe (21, 22), and one study was conducted in Japan (12). Cohort sizes ranged from 3319 (22) to 327,396 (21), and the number of EOC cases varied from 86 (12) to 878 (21) cases. The longest total duration of breastfeeding varied from 13 mo (21) to >24 mo (22). The shortest total duration of breastfeeding varied from never (4, 22) to <1 mo (21).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of studies of breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk1

| First author (reference), publication year, country, study design | Cases/subjects (age), duration of follow-up | Lactation categories (exposure/case assessment) | RR/OR (95% CI) | Matched/adjusted factors |

| Prospective study | ||||

| Weiderpass et al (12), 2012, Japan, CS | 86/45,748 (40–69 y), 16 y | Ever compared with never | 1.0 (0.5, 1.9) | Age, study center, parity, age at first birth, use of exogenous hormones, menopausal status at enrollment, height, BMI, smoking status, exposure to second-hand smoke, physical activity during leisure time, usual sleep duration, and family history of cancer in first-degree relatives |

| (Self-questionnaire/cancer registry) | ||||

| Tsilidis et al (21), 2011, European, CS | 878/327,396 (NA), 9 y | Ever compared with never | 0.86 (0.70, 1.07) | Participating center and age at recruitment, smoking status, BMI, unilateral ovariectomy, simple hysterectomy, menopausal HRT, duration of OC use, age at menopause, and no. of full-term pregnancies |

| Total >13 compared with ≤1 mo | 0.88 (0.69, 1.13) | |||

| (Self-questionnaire/medical records) | ||||

| Antoniou et al (22), 2009, European, CS | 253/3319 (>18 y), 8 y | Ever compared with never | 0.88 (0.62, 1.26) | Duration of OC use |

| Total >24 mo compared with never | 0.71 (0.29, 1.70) | |||

| (Self-questionnaire/NA) | ||||

| Danforth et al (4), 2007, United States, CS | 342/121,701 (30–55 y), 16 y | Ever compared with never | 0.86 (0.76, 1.06) | Age, parity, duration of OC use, tubal ligation, and age at menarche |

| 49/116,671 (25–42 y), 10 y | Total ≥18 mo compared with never | 0.66 (0.46, 0.96) | ||

| (Self-questionnaire/medical record) | ||||

| Mink et al (13), 1996, United States, CS | 97/31,396 (55–69 y), 7 y | Ever compared with never | 1.03 (0.66, 1.61) | Age |

| (Self-questionnaire/cancer registry) | ||||

| Case-control study | ||||

| Jordan et al (23), 2012, United States, PC-CS | 881/1345 (35–74 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.78 (0.64, 0.94) | Reference year, education, no. of live births, and duration of hormonal contraception |

| Total ≥18 mo compared with none | 0.70 (0.53, 0.93) | |||

| Average ≥18 mo compared with none | 0.56 (0.32, 0.98) | |||

| (Interviewer/cancer registry) | ||||

| Titus-Ernstoff et al (17), 2010, United States, PC-CS | 829/1009 (mean: 54.5/52.6 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.75 (0.62, 0.92) | Age, study center, OC use, parity, and age at most recent birth |

| Average ≥12 mo compared with never | 0.58 (0.37, 0.93) | |||

| (Interviewer/medical records) | ||||

| Jordan et al (14), 2010, Australia, PC-CS | 1092/1288 (mean: 58.4/57.0 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.77 (0.61, 0.96) | Age, state of residence, parity, age at first full-term birth, duration of hormonal contraceptive use (in mo), menopausal status, smoking, previous tubal ligation or hysterectomy, alcohol consumption, education, and family history of ovarian or breast cancer (result of average duration only adjusted for parity) |

| Total >42 mo compared with never | 0.45 (0.25, 0.82) | |||

| Average >42 mo compared with never | 0.61 (0.43, 0.82) | |||

| (Self-questionnaire/medical records) | ||||

| Moorman et al (24), 2008, United States, PC-CS2 | 896/967 (20–74 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.77 (0.63, 0.96) | Age, race, family history of breast or ovarian cancer, age at menarche, tubal ligation, infertility, BMI, duration of OC use, and age at last oral contraceptive use |

| Total >12 mo compared with never | 0.84 (0.51, 1.40) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/cancer registry) | ||||

| McLaughlin et al (25), 2007, multinational study, PC-CS | 799/2424 (27–82 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.74 (0.56, 0.97) | Parity, OC use, tubal ligation, ethnicity, year of birth, mutation type, and country of residence |

| Average >12 mo compared with never | 0.64 (0.47, 0.91) | |||

| (Self-questionnaire/cancer registry) | ||||

| Huusom et al (15), 2006, Denmark, PC-CS | 202/1564 (35–79 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.79 (0.47, 1.35) | Age, childbirth, no. of additional births, age at first birth, duration of OC use, smoking, and intake of milk |

| Total ≥25 mo compared with never | 0.33 (0.10, 1.10) | |||

| (Self-questionnaire/cancer registry) | ||||

| Gronwald et al (26), 2006, Poland, HC-CS2 | 150/150 (NA) | Ever compared with never | 1.00 (0.52, 1.93) | Year of birth |

| Total >12 mo compared with never | 1.0 (0.4, 2.6) | |||

| (Self-questionnaire/medical records) | ||||

| Chiaffarino et al (16), 2005, Italy, HC-CS | 1031/2411 (median: 56/57 y) | Ever compared with never | 1.16 (0.93, 1.43) | Age, study center, education, parity, OC use, and family history of ovarian or breast cancer in first-degree relatives |

| Total ≥17 mo compared with never | 1.21 (0.85, 1.71) | |||

| Average ≥8 compared with<3 mo | 1.18 (0.93, 1.50) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/cancer registry) | ||||

| Zhang et al (29, 46), 2004, China, C-CS | 254/652 (mean: 46.8/48.0 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.50 (0.30, 0.82) | Age, locality, education, family income, BMI, total energy intake, tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, ovarian cancer in first-degree relatives, parity (for duration of lactation), and OC use (for duration of lactation) |

| Total >12 compared with ≤4 mo | 0.51 (0.30, 0.89) | |||

| Average >12 compared with 0 mo | 0.63 (0.31, 1.31) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/medical records) | ||||

| Rossing et al (27), 2004, United States, PC-CS2 | 378/1637 (35–54 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.76 (0.58, 0.99) | Age, race, study site, duration of OC use, and no. of full-term births |

| Total >12 mo compared with never | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/cancer registry) | ||||

| Mills et al (28), 2004, United States, PC-CS2 | 256/1122 (mean: 56.6/55 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.52 (0.38, 0.71) | Age, race-ethnicity, and OC use |

| Total >12 mo compared with never | 0.29 (0.17, 0.49) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/cancer registry) | ||||

| Yen et al (31), 2003, Taiwan, HC-CS2 | 86/369 (median: 47/44 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.61 (0.35, 1.07) | Age, treatment hospital, date of admission, and no. of live births |

| Total ≥24 mo compared with never | 0.55 (0.29, 1.01) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/medical records) | ||||

| Tung et al (30), 2003, United States, PC-CS | 558/607 (NA) | Ever compared with never | 0.6 (0.4, 0.7) | Age, ethnicity, study site, education, OC use, tubal ligation, and parity |

| Average >16 mo compared with never | 0.6 (0.4, 0.8) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/cancer registry) | ||||

| Riman et al (47), 2002, Sweden, PC-CS2 | 655/3899 (mean: 62.4/63.4 y) | Total ≥12 compared with <1 mo | 0.87 (0.56, 1.35) | Age, parity, BMI, age at menopause, duration of OC use, and ever use of hormone replacement treatment |

| (Self-questionnaire/cancer registry) | ||||

| Riman et al (32), 2001, Sweden, PC-CS2 | 193/3899 (mean: 61.8/63.4 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.48 (0.28, 0.83) | Age, parity, BMI, and age at menopause and ever use of OC, unopposed estrogens with cyclic progestin, and estrogens with continuous progestin |

| Total ≥12 mo compared with never | 0.47 (0.24, 0.94) | |||

| (Self-questionnaire/cancer registry) | ||||

| Ness et al (34), 2000, United States, PC-CS2 | 767/1367 (20–69 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.85 (0.68, 1.06) | Age, parity, family history of ovarian cancer, and race |

| Total ≥24 mo compared with never | 0.7 (0.4, 1.0) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/cancer registry) | ||||

| Greggi et al (33), 2000, Italy, HC-CS | 440/868 (median: 54/55 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.58 (0.42, 0.81) | Age, education, parity, OC use, family history of ovarian cancer, and age at first birth |

| Total >12 mo compared with never | 0.5 (0.4, 0.8) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/medical records) | ||||

| Salazar-Martinez et al (35), 1999, Mexico, HC-CS | 84/668 (mean: 52.8/54.6 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.31 (0.18, 0.53) | Age, hormonal use, no. of pregnancies, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, physical activity, menopausal status, and body build index |

| Total ≥25 mo compared with never | 0.36 (0.19, 0.69) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/medical records) | ||||

| Hirose et al (36), 1999, Japan, HC-CS | 99/25,488 (≥30 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.89 (0.43, 1.85) | Age and BMI |

| Average ≥12 mo compared with never | 0.70 (0.31, 1.55) | |||

| (Self-questionnaire/cancer registry) | ||||

| Mori et al (37), 1998, Japan, HC-CS | 89/323 (30–85 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.59 (0.21, 1.72) | Age |

| (Trained interviewer/medical records) | ||||

| Siskind (38), 1997, Australia, PC-CS2 | 824/855 (18–79 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.79 (0.61, 1.03) | No. of live-born children, age, use of OC, education, smoking history, and for all women, menopausal status |

| Total >36 mo compared with never | 0.77 (0.34, 1.75) | |||

| (Self-questionnaire/medical records) | ||||

| Rosenblatt et al (39), 1993, multinational study, HC-CS3 | 393/2565 (40–79 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.86 (0.57, 1.28) | Age, center, date of diagnosis, and no. of live births (only for total duration) |

| Total >48 compared with ≤4 mo | 0.80 (0.45, 1.42) | |||

| Average ≥13 compared with 0–2 mo | 0.68 (0.43, 1.07) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/medical records) | ||||

| Chen et al (40), 1992, China, PC-CS2 | 112/224 (mean: 48.5/49 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.92 (0.41, 2.07) | Age, education, street office or township and parity |

| Total ≥36 mo compared with never | 1.1 (0.4, 2.9) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/cancer registry) | ||||

| Gwinn et al (41), 1990, United States, PC-CS3 | 436/3833 (20–54 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.52 (0.42, 0.64) | Age |

| Total ≥24 mo compared with never | 0.27 (0.13, 0.58) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/medical records) | ||||

| Hartge et al (43), 1989, United States, HC-CS2 | 296/343 (mean: 54.4/54.7 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.84 (0.55, 1.28) | Age, race, hospital, and parity |

| Total 19–110 mo compared with never | 1.1 (0.5, 2.6) | |||

| (Trained interviewer/medical records) | ||||

| Booth et al (42), 1989, United Kingdom, HC-CS2 | 235/451 (mean: 52.4/51.4 y) | Ever compared with never | 1.23 (0.79, 1.93) | Age, social class, and no. of live births |

| Total ≥25 mo compared with never | 3.4 (1.1, 10.8) | |||

| (Interviewer/medical records) | ||||

| Mori et al (44), 1988, Japan, HC-CS | 110/220 (NA) | Ever compared with never | 0.7 (0.3, 1.9) | Year of birth and year of survey |

| (Interviewer/medical records) | ||||

| Harlow et al (48), 1988, United States, PC-CS | 116/158 (20–79 y) | Total >9 compared with <1 mo | 0.3 (0.1, 0.7) | Parity, age at diagnosis, and use of OC |

| (Interviewer/cancer registry) | ||||

| Cramer et al (45), 1983, United States, PC-CS2 | 215/215 (mean: 53.2/53.5 y) | Ever compared with never | 0.90 (0.57, 1.43) | Age, race, and place of residence |

| (Interviewer/NA) | ||||

| Risch et al (49), 1983, United States, PC-CS3 | 284/705 (20–74 y) | Total ≥36 compared with ≤24 mo | 0.82 (0.62, 1.09) | NA |

| (Trained interviewer/cancer registry) |

C-CS, case-control study; CS, cohort study; HC-CS, hospital-based case-control study; HRT, hormone-replacement therapy; NA, not available; OC, oral contraceptive; PC-CS, population-based case-control study.

RR was recalculated by the method proposed by Hamling et al (56).

OR and 95% CI were calculated from published data with EpiCalc 2000 software (version 1.02; Brixton Health).

Of 30 case-control studies, 12 studies were conducted in the United States (17, 23, 24, 27, 28, 30, 34, 41, 43, 45, 48, 49), 3 studies were conducted in China (29, 31, 40), 3 studies were conducted in Japan (36, 37, 44), 2 studies each were conducted in Australia (14, 38), Sweden (32, 47), and Italy (16, 33), and one study each was conducted in Denmark (15), Poland (26), the United Kingdom (42), and Mexico (35). Two studies covered multiple countries (25, 39). The number of cases enrolled in these studies ranged from 84 (35) to 1092 (14) cases, and the number of control subjects varied from 150 (26) to 25,488 (36) subjects. Control subjects were drawn from the general population in 18 studies (14, 15, 17, 23–25, 27, 28, 30, 32, 34, 38, 40, 41, 45, 47–49), hospitals in 11 studies (16, 26, 31, 33, 35–37, 39, 42–44), and both places in one study (29). The longest total duration of breastfeeding varied from 9 mo (48) to >48 mo (39). The shortest total duration of breastfeeding varied from never (14–17, 23–28, 30–36, 38, 40–43) to <24 mo (49).

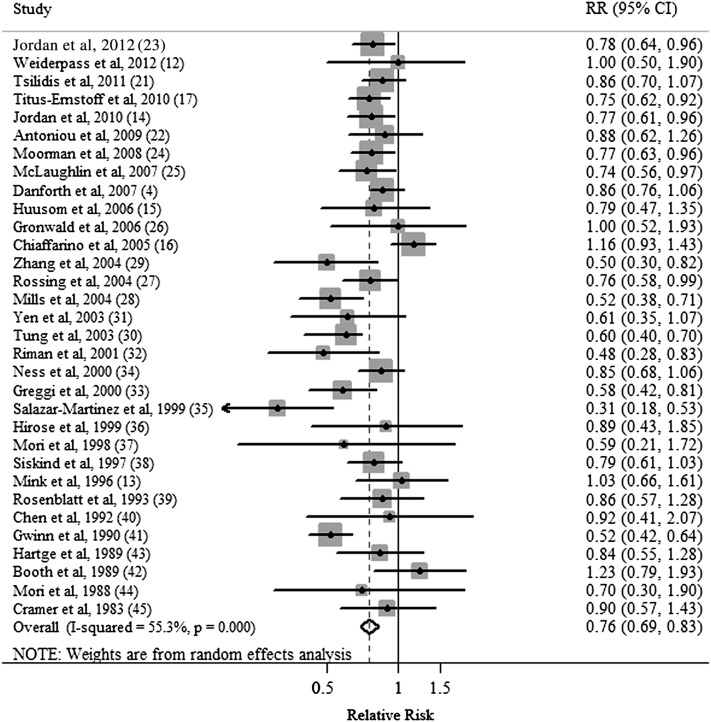

Breastfeeding

Five cohort (4, 12, 13, 21, 22, 48) and 27 case-control (14–17, 23–45) studies investigated the association between ever breastfeeding and EOC risk. The summary RR of EOC for the ever compared with never categories of breastfeeding was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.69, 0.83) with moderate heterogeneity (Q = 69.4, P < 0.001, I2 = 55.3%) (Table 2, Figure 2). There was no indication of a publication bias by using Egger's test (P-bias = 0.495) or Begg's test (P-bias = 0.538), and no asymmetry was observed in funnel plots when inspected visually.

TABLE 2.

Summary risk estimates of the association between breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk

| Studies | Summary RR (95% CI) | Q statistic | I2 | Ph1 | Ph2 | |

| n | % | |||||

| Overall | 32 | 0.76 (0.69–0.83) | 69.40 | 55.3 | <0.001 | — |

| Subgroup analyses | ||||||

| Study design | 0.090 | |||||

| Cohort studies | 5 | 0.88 (0.78, 0.99) | 0.73 | 0 | 0.947 | |

| Case-control studies | 27 | 0.74 (0.67, 0.82) | 62.36 | 58.3 | <0.001 | |

| Exposure assessment | 0.065 | |||||

| Trained interviewer | 15 | 0.68 (0.57, 0.80) | 51.59 | 72.9 | <0.001 | |

| Self-administered questionnaire | 12 | 0.82 (0.75, 0.90) | 7.06 | 0 | 0.794 | |

| Type of control subjects | 0.158 | |||||

| Population based | 16 | 0.73 (0.68, 0.78) | 22.91 | 34.5 | 0.086 | |

| Hospital based | 10 | 0.78 (0.60, 1.02) | 31.01 | 71.0 | <0.001 | |

| Study population | 0.862 | |||||

| Asians | 7 | 0.69 (0.53, 0.89) | 3.99 | 0 | 0.678 | |

| Americans | 13 | 0.71 (0.63, 0.81) | 35.90 | 66.6 | <0.001 | |

| Europeans | 8 | 0.85 (0.69, 1.06) | 19.75 | 64.6 | 0.006 | |

| Cancer grading | 0.645 | |||||

| Invasive | 5 | 0.62 (0.53, 0.72) | 6.14 | 34.9 | 0.189 | |

| Borderline | 4 | 0.57 (0.44, 0.74) | 2.53 | 0 | 0.470 | |

| Cancer histotype | 0.267 | |||||

| Serous | 7 | 0.82 (0.68, 0.99) | 13.91 | 56.9 | 0.031 | |

| Mucinous | 6 | 0.80 (0.64, 1.00) | 7.10 | 29.6 | 0.213 | |

| Endometrioid | 3 | 0.65 (0.47, 0.89) | 2.10 | 5.0 | 0.349 | |

| Clear cell | 2 | 0.67 (0.39, 1.15) | 0.92 | 0 | 0.336 | |

| Adjustment for confounders | ||||||

| Parity | 0.285 | |||||

| Yes | 22 | 0.78 (0.71, 0.85) | 42.23 | 50.3 | 0.004 | |

| No | 10 | 0.70 (0.57, 0.87) | 18.55 | 51.5 | 0.029 | |

| BMI | 0.803 | |||||

| Yes | 5 | 0.79 (0.69, 0.91) | 4.43 | 9.7 | 0.351 | |

| No | 27 | 0.75 (0.68, 0.83) | 64.71 | 59.8 | <0.001 | |

| OC3 use | 0.782 | |||||

| Yes | 17 | 0.77 (0.70, 0.84) | 32.56 | 50.9 | 0.008 | |

| No | 15 | 0.87 (0.69, 1.09) | 34.97 | 60.6 | 0.001 | |

| Smoking | 0.505 | |||||

| Yes | 7 | 0.71 (0.57, 0.88) | 15.32 | 60.8 | 0.018 | |

| No | 25 | 0.77 (0.70, 0.85) | 54.00 | 55.6 | <0.001 |

P value for heterogeneity within each subgroup.

P value for heterogeneity between subgroups with meta-regression analysis.

OC, oral contraceptive.

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot (random-effects model) of ever breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk. Squares indicate study-specific RRs (the size of the square reflects the study-specific statistical weight); horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs; the diamond indicates the summary RR estimate with its 95% CI.

Longest compared with shortest total durations of breastfeeding

Four case-control studies (17, 25, 36, 63) reported the average duration of breastfeeding, and these studies were excluded from the analysis. Three cohort (4, 21, 22) and 23 case-control (14–16, 23, 24, 26–29, 31–35, 38–43, 47–49) studies investigated the association between the total duration of breastfeeding and EOC risk. The summary RR of EOC for the longest compared with shortest total duration categories of breastfeeding was 0.65 (95% CI: 0.55, 0.78) with significant heterogeneity (Q = 70.26, P < 0.001, I2 = 64.4%) (Table 3). There was no indication of a publication bias by using Egger's test (P-bias = 0.068) or Begg's test (P-bias = 0.741), and no asymmetry was seen in funnel plots when inspected visually.

TABLE 3.

Summary risk estimates of the association between the total duration of breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk: longest compared with shortest durations1

| Studies | Summary RR (95% CI) | Q statistic | I2 | Ph2 | Ph3 | |

| n | % | |||||

| Overall | 26 | 0.65 (0.55, 0.78) | 70.26 | 64.4 | <0.001 | — |

| Subgroup analyses | ||||||

| Study design | 0.511 | |||||

| Cohort studies | 3 | 0.80 (0.66, 0.98) | 1.69 | 0 | 0.429 | |

| Case-control studies | 23 | 0.63 (0.52, 0.78) | 67.25 | 67.3 | <0.001 | |

| Exposure assessment | 0.790 | |||||

| Trained interviewer | 14 | 0.61 (0.49, 0.76) | 49.54 | 73.8 | <0.001 | |

| Self-administered questionnaire | 9 | 0.75 (0.63, 0.88) | 9.33 | 14.3 | 0.315 | |

| Type of control subjects | 0.185 | |||||

| Population based | 14 | 0.57 (0.45, 0.71) | 27.98 | 53.5 | 0.009 | |

| Hospital based | 8 | 0.81 (0.53, 1.21) | 31.11 | 77.5 | <0.001 | |

| Study population | 0.365 | |||||

| Asians | 3 | 0.66 (0.43, 1.00) | 1.36 | 0 | 0.505 | |

| Americans | 11 | 0.55 (0.43, 0.71) | 25.93 | 61.4 | 0.004 | |

| Europeans | 9 | 0.81 (0.59, 1.10) | 27.46 | 70.9 | 0.001 | |

| Cancer grading | 0.291 | |||||

| Invasive | 4 | 0.55 (0.36, 0.84) | 7.95 | 62.3 | 0.047 | |

| Borderline | 5 | 0.41 (0.28, 0.60) | 1.67 | 0 | 0.797 | |

| Cancer histotype | 0.258 | |||||

| Serous | 6 | 0.75 (0.59, 0.96) | 1.78 | 0 | 0.879 | |

| Mucinous | 4 | 0.61 (0.19, 1.94) | 12.04 | 75.1 | 0.007 | |

| Endometrioid | 3 | 0.59 (0.35, 0.98) | 2.64 | 24.4 | 0.267 | |

| Clear cell | 1 | 0.24 (0.06, 0.97) | NA | NA | NA | |

| Adjustment for confounders | ||||||

| Parity | 0.318 | |||||

| Yes | 21 | 0.68 (0.59, 0.82) | 50.60 | 60.5 | <0.001 | |

| No | 5 | 0.53 (0.30, 0.94) | 17.53 | 77.2 | 0.002 | |

| BMI | 0.406 | |||||

| Yes | 5 | 0.81 (0.67, 0.98) | 3.44 | 0 | 0.486 | |

| No | 21 | 0.63 (0.50, 0.78) | 64.46 | 69.0 | <0.001 | |

| OC use | 0.428 | |||||

| Yes | 16 | 0.62 (0.50, 0.77) | 48.25 | 68.9 | <0.001 | |

| No | 10 | 0.73 (0.53, 1.00) | 22.00 | 59.1 | 0.009 | |

| Smoking | 0.521 | |||||

| Yes | 6 | 0.58 (0.40, 0.85) | 11.15 | 55.1 | 0.049 | |

| No | 20 | 0.67 (0.55, 0.83) | 59.07 | 67.8 | <0.001 |

NA, not available; OC, oral contraceptive.

P value for heterogeneity within each subgroup.

P value for heterogeneity between subgroups with meta-regression analysis.

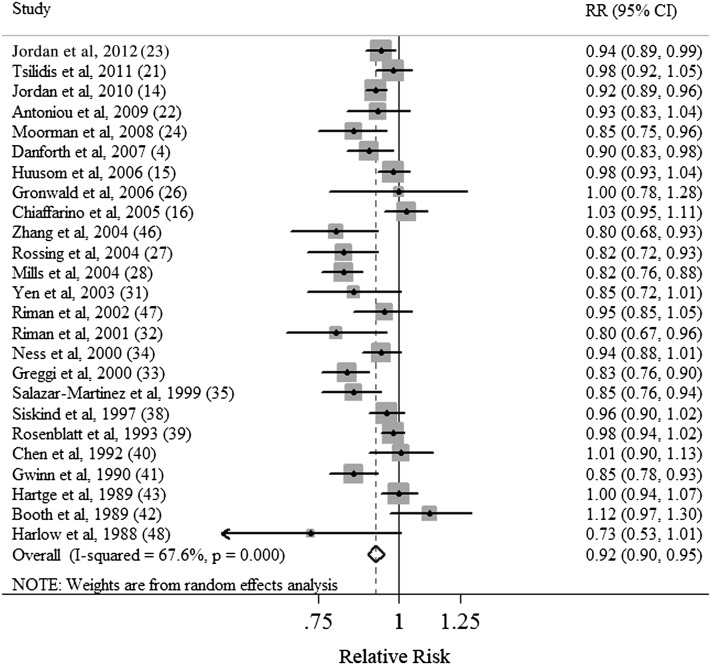

Dose-response analysis of total duration of breastfeeding

Three cohort (4, 21, 22) and 22 case-control (14–16, 23, 24, 26–28, 31–35, 38–43, 46–48) studies were included in the dose-response analysis. The summary RR for each increase by 5 mo for breastfeeding duration was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.90, 0.95) with significant heterogeneity (Q = 74.12, P < 0.021, I2 = 67.6%) (Table 4, Figure 3). Publication bias was not evident by using Egger's test (P = 0.090) or Begg's test (P = 0.161) or by visual inspection of the funnel plot.

TABLE 4.

Summary risk estimates of the association between the total duration of breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk: a dose-response analysis (per 5-mo increase)1

| Studies | Summary RR (95% CI) | Q statistic | I2 | Ph2 | Ph3 | |

| n | % | |||||

| Overall | 25 | 0.92 (0.90, 0.95) | 74.12 | 67.6 | <0.001 | — |

| Subgroup analyses | ||||||

| Study design | 0.686 | |||||

| Cohort studies | 3 | 0.95 (0.90, 0.99) | 2.57 | 22.1 | 0.277 | |

| Case-control studies | 22 | 0.92 (0.90, 0.95) | 71.35 | 70.6 | <0.001 | |

| Exposure assessment | 0.160 | |||||

| Trained interviewer | 13 | 0.90 (0.85, 0.95) | 55.21 | 78.3 | <0.001 | |

| Self-administered questionnaire | 9 | 0.94 (0.92, 0.96) | 9.77 | 18.1 | 0.281 | |

| Type of control subjects | ||||||

| Population based | 14 | 0.57 (0.45, 0.71) | 27.98 | 53.5 | 0.009 | |

| Hospital based | 8 | 0.81 (0.53, 1.21) | 31.11 | 77.5 | <0.001 | |

| Study population | 0.925 | |||||

| Asians | 3 | 0.89 (0.77, 1.04) | 6.45 | 69.0 | 0.040 | |

| Americans | 10 | 0.89 (0.85, 0.93) | 27.48 | 67.3 | 0.001 | |

| Europeans | 9 | 0.96 (0.90, 1.01) | 24.07 | 66.8 | 0.002 | |

| Cancer grading | 0.770 | |||||

| Invasive | 4 | 0.88 (0.84, 0.92) | 4.99 | 39.9 | 0.172 | |

| Borderline | 5 | 0.89 (0.82, 0.96) | 11.43 | 65.0 | 0.022 | |

| Cancer histotype | 0.074 | |||||

| Serous | 6 | 0.94 (0.90, 0.98) | 2.17 | 0 | 0.824 | |

| Mucinous | 4 | 0.84 (0.72, 0.99) | 8.46 | 64.6 | 0.037 | |

| Endometrioid | 3 | 0.86 (0.79, 0.95) | 2.63 | 24.0 | 0.268 | |

| Clear cell | 1 | 0.62 (0.41, 0.94) | NA | NA | NA | |

| Adjustment for confounders | ||||||

| Parity | 0.169 | |||||

| Yes | 21 | 0.93 (0.91, 0.96) | 55.55 | 64.0 | <0.001 | |

| No | 4 | 0.86 (0.82, 0.90) | 4.93 | 39.2 | 0.177 | |

| BMI | 0.438 | |||||

| Yes | 5 | 0.89 (0.82, 0.97) | 10.79 | 62.9 | 0.029 | |

| No | 20 | 0.93 (0.90, 0.96) | 63.04 | 69.9 | <0.001 | |

| OC use | 0.219 | |||||

| Yes | 16 | 0.91 (0.88, 0.94) | 46.58 | 67.8 | <0.001 | |

| No | 9 | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) | 22.37 | 64.2 | 0.004 | |

| Smoking | 0.521 | |||||

| Yes | 6 | 0.93 (0.89, 0.98) | 12.85 | 61.1 | 0.025 | |

| No | 19 | 0.92 (0.88, 0.96) | 61.15 | 70.6 | <0.001 |

NA, not available; OC, oral contraceptive.

P value for heterogeneity within each subgroup.

P value for heterogeneity between subgroups with meta-regression analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot (random-effects model) of the total duration of breastfeeding (dose-response analyses on the basis of increases of 5 mo in duration) and ovarian cancer risk. Squares indicate study-specific RRs (the size of the square reflects the study-specific statistical weight); horizontal lines indicate 95% CIs; the diamond indicates the summary RR estimate with its 95% CI.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

In subgroup analyses of ever breastfeeding and EOC risk, all strata showed inverse associations, and there was no evidence of significant heterogeneity between subgroups with meta-regression analyses (Table 2). Similar results were also observed in dose-response analyses of the relation between the total duration of breastfeeding and EOC risk (Table 4). We further focused on the difference between studies in which associations with breastfeeding were of primary interest (4, 14–17, 21–25, 29, 30, 34, 35, 38, 39, 41, 44–46, 48, 49) and studies that mainly dealt with other associations (12, 13, 26–28, 31–33, 36, 37, 40, 42, 43, 47). However, results of the meta-regression and tests for heterogeneity did not show a significant difference in the analyses of ever breastfeeding or in breastfeeding duration (data not shown). When stratified by the adjustment for potential confounders, we did not shown a significant difference between estimates adjusted and those not adjusted for specific factors (Tables 2–4).

In a sensitivity analysis, we sequentially removed one study at a time and reanalyzed the data. The 32 study-specific RRs of ever breastfeeding ranged from a low of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.68, 0.80) after omission of the study by Chiaffarino et al (16) to a high of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.71, 0.84) after omission of the study by Gwinn et al (41). Similar analyses were also carried out in the dose-response analysis of total breastfeeding duration, with study-specific RRs ranging from a low of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.89, 0.95) after omission of the study by Chiaffarino et al (16) to a high of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.90, 0.96) after omission of the study by Mills et al (28).

DISCUSSION

The findings from this meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies indicated that ever breastfeeding had an almost 24% reduction in EOC risk compared with that for never breastfeeding. The risk reduction was similar for borderline and invasive EOC, and was consistently reported in case-control and cohort studies. In addition, results of dose-response analyses suggested that risk of EOC decreased by 8% for each 5-mo increase in total breastfeeding duration.

The inverse association between breastfeeding and risk of borderline EOC as well as invasive EOC is biologically plausible. Recently, 2 hypotheses have dominated when the cause of ovarian pathogenesis has been considered. One of these hypotheses proposes that, because of incessant ovulation, repeated trauma to the ovary caused by ovulation may increase ovarian cancer risk (5). The other hypothesis suggests that excessive concentrations of gonadotropins increase EOC risk through increased estrogen stimulation, which promotes cell proliferation and increases the opportunity for malignant transformation (8). Research also has indicated that breastfeeding may reset pregnancy-related changes, possibly through hypothalamic-pituitary–regulated mechanisms that mediate EOC risk (17). Breastfeeding also causes gonadotrophin suppression, which leads to low estrogen concentration and induces a state of relative quiescence in women's ovaries by suppressing the release of luteinizing hormone and, thereby, preventing ovulation. Thus, according to these hypotheses, ever breastfeeding and a longer duration of breastfeeding would be expected to decrease EOC risk through their effects on ovulation and gonadotropin concentrations.

Significant inverse associations for the duration of breastfeeding on EOC risk were only observed in American populations (Tables 3 and 4), which could have been attributed to a greater variation in breastfeeding patterns and duration. Rosenblatt et al (39) reported that nearly 90% of the study population breastfed for ≥1 mo in a multinational case-control study, which resulted in a referent group of women who breastfed for 0–4 mo instead of women who never breastfed. However, populations in which more than one-half of the women had never breastfed were observed in several population-based case-control studies in United States (24, 27). By comparison, Salazar-Martinez et al (35) reported mean breastfeeding duration of 12.7 mo/child in 668 hospital-based controls in Mexico, whereas Mori et al (37) reported a mean breastfeeding duration of 8.5 mo/child in 323 hospital-based controls in Japan.

Although the average duration of breastfeeding per child has more public health applicability than the total duration, only 9 case-control studies (14, 16, 17, 23, 25, 30, 36, 39, 46) reported the results of this average measurement; therefore, we only carried out analyses for the total duration in the main study. Dose-response results for the average duration of breastfeeding per child (summary RR for a 5-mo increase in duration: 0.91 (95% CI: 0.85, 0.98), which was calculated from 7 (16, 17, 23, 25, 36, 39, 46) of these 9 studies) was similar to the results of the total duration, which also supported our findings. Besides, the majority of included studies adjusted for parity or the number of live births.

Although not all the studies presented results by histologic subtype and cancer grade, our meta-analysis suggested a significant inverse association for breastfeeding with invasive, borderline, serous, and endometrioid EOC. These results were consistent in the dose-response analyses of breastfeeding duration. However, because of the limited number of studies that reported histologic subtypes, the results should be interpreted with caution.

The strengths of this meta-analysis included the large sample size of 14,465 cases and 706,152 noncases. This sample size should have provided sufficient statistical power to detect the putative association between ever breastfeeding and the duration of breastfeeding with risk of EOC. In addition, our study considered a number of subgroups to evaluate heterogeneity. Our study also has several limitations. First, as a meta-analysis of observational studies, it was prone to biases (eg, recall and selection bias) inherent in the original studies. Cohort studies are less susceptible to bias than case-control studies because, in the prospective design, information on exposures is collected before the diagnosis of the disease. Although the results of the meta-regression showed no evidence of significant heterogeneity between subgroups, summary association estimates were slightly different in subgroup analyses by study design and exposure assessment. It is possible that the relations reported by case-control studies may have been overstated as a result of recall or interviewer bias. In addition, some recent cohort studies provided detailed information of adjustment for confounders, whereas some early case-control studies adjusted for fewer factors. Thus, more large studies, especially prospective studies, are warranted in the future.

A second limitation was that individual studies may have failed to control for potential confounders, which may have introduce bias in an unpredictable direction. Ever breastfeeding and a longer duration of breastfeeding are often associated with other hormone-dependent or reproductive factors, including lower levels of BMI (64), a lower prevalence of OC use (65), a higher parity number, and a lower prevalence of smoking (66). Many, but not all, of the studies adjusted for potential confounding factors. However, an inverse association was still observed when we stratified results according to the adjustment for confounding factors, and the evidence of meta-regression analyses indicated that the adjustment for these confounders was not a source of heterogeneity.

Third, significant heterogeneity and a possible publication bias must be considered. There was significant heterogeneity in the pooled analysis of ever breastfeeding (Q = 69.40, P < 0.001, I2 = 55.3%) and in the dose-response analysis of the total breastfeeding duration (Q = 74.12, P < 0.021, I2 = 67.6%). Despite the numerous subgroup and sensitivity analyses that were carried out, heterogeneity still existed in our study. To our knowledge, the category of duration of breastfeeding, especially the longest duration, differed between studies and may have contributed to the heterogeneity in results. However, few of the included studies reported how they categorized the duration of breastfeeding, and thus, we hardly considered this point in the subgroup analysis and ruled out the heterogeneity thoroughly. Publication bias can be a problem in meta-analyses of published studies; however, we showed no statistical evidence of a publication bias in the meta-analysis, and there did not appear to be asymmetry in funnel plots when inspected visually.

In conclusion, findings from this meta-analysis suggest that breastfeeding, particularly a longer duration of breastfeeding, was inversely associated with risk of EOC. The results were consistent with benefits of breastfeeding proposed by the US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (67) and may have implications for women's decisions regarding breastfeeding in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—N-NL, Q-JW, T-TG, and EV: designed and conducted research; NNL, Q-JW, and T-TG: analyzed data; N-NL and Q-JW: wrote the manuscript; N-NL, Q-JW, and EV: contributed to manuscript revisions; NNL: had primary responsibility for the final content of the manuscript; and all authors: read, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript. None of the authors had a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2012;62:10–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Preventive Services Task Force Guide to clinical preventive services. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danforth KN, Tworoger SS, Hecht JL, Rosner BA, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. Breastfeeding and risk of ovarian cancer in two prospective cohorts. Cancer Causes Control 2007;18:517–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fathalla MF. Incessant ovulation–a factor in ovarian neoplasia? Lancet 1971;2:163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hankinson SE, Danforth KN. Ovarian Cancer. : Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni J, eds. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2006:1013–26 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whittemore AS, Harris R, Itnyre J. Characteristics relating to ovarian cancer risk: collaborative analysis of 12 US case-control studies. IV. The pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Collaborative Ovarian Cancer Group. Am J Epidemiol 1992;136:1212–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramer DW, Welch WR. Determinants of ovarian cancer risk. II. Inferences regarding pathogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst 1983;71:717–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gong TT, Wu QJ, Vogtmann E, Lin B, Wang YL. Age at menarche and risk of ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer 2013;132:2894–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNeilly AS. Lactational control of reproduction. Reprod Fertil Dev 2001;13:583–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Cancer Resarch Fund/American Institue for Cancer Research Food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington, DC: AICR, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiderpass E, Sandin S, Inoue M, Shimazu T, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Sawada N, Yamaji T, Tsugane S. Risk factors for epithelial ovarian cancer in Japan - results from the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study cohort. Int J Oncol 2012;40:21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mink PJ, Folsom AR, Sellers TA, Kushi LH. Physical activity, waist-to-hip ratio, and other risk factors for ovarian cancer: a follow-up study of older women. Epidemiology 1996;7:38–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan SJ, Siskind V, C Green A, Whiteman DC, Webb PM. Breastfeeding and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2010;21:109–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huusom LD, Frederiksen K, Hogdall EV, Glud E, Christensen L, Hogdall CK, Blaakaer J, Kjaer SK. Association of reproductive factors, oral contraceptive use and selected lifestyle factors with the risk of ovarian borderline tumors: a Danish case-control study. Cancer Causes Control 2006;17:821–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiaffarino F, Pelucchi C, Negri E, Parazzini F, Franceschi S, Talamini R, Montella M, Ramazzotti V, La Vecchia C. Breastfeeding and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in an Italian population. Gynecol Oncol 2005;98:304–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Titus-Ernstoff L, Rees JR, Terry KL, Cramer DW. Breast-feeding the last born child and risk of ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2010;21:201–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, Trikalinos TA, Lau J. A summary of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's evidence report on breastfeeding in developed countries. Breastfeed Med 2009;4(Suppl 1):S17–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsilidis KK, Allen NE, Key TJ, Dossus L, Lukanova A, Bakken K, Lund E, Fournier A, Overvad K, Hansen L, et al. Oral contraceptive use and reproductive factors and risk of ovarian cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Br J Cancer 2011;105:1436–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antoniou AC, Rookus M, Andrieu N, Brohet R, Chang-Claude J, Peock S, Cook M, Evans DG, Eeles R, Nogues C, et al. Reproductive and hormonal factors, and ovarian cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the International BRCA1/2 Carrier Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:601–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jordan SJ, Cushing-Haugen KL, Wicklund KG, Doherty JA, Rossing MA. Breast-feeding and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2012;23:919–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moorman PG, Calingaert B, Palmieri RT, Iversen ES, Bentley RC, Halabi S, Berchuck A, Schildkraut JM. Hormonal risk factors for ovarian cancer in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:1059–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLaughlin JR, Risch HA, Lubinski J, Moller P, Ghadirian P, Lynch H, Karlan B, Fishman D, Rosen B, Neuhausen SL, et al. Reproductive risk factors for ovarian cancer in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations: a case-control study. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:26–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gronwald J, Byrski T, Huzarski T, Cybulski C, Sun P, Tulman A, Narod SA, Lubinski J. Influence of selected lifestyle factors on breast and ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1 mutation carriers from Poland. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2006;95:105–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossing MA, Tang MT, Flagg EW, Weiss LK, Wicklund KG. A case-control study of ovarian cancer in relation to infertility and the use of ovulation-inducing drugs. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:1070–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mills PK, Riordan DG, Cress RD. Epithelial ovarian cancer risk by invasiveness and cell type in the Central Valley of California. Gynecol Oncol 2004;95:215–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang M, Lee AH, Binns CW. Reproductive and dietary risk factors for epithelial ovarian cancer in China. Gynecol Oncol 2004;92:320–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tung KH, Goodman MT, Wu AH, McDuffie K, Wilkens LR, Kolonel LN, Nomura AM, Terada KY, Carney ME, Sobin LH. Reproductive factors and epithelial ovarian cancer risk by histologic type: a multiethnic case-control study. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:629–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yen ML, Yen BL, Bai CH, Lin RS. Risk factors for ovarian cancer in Taiwan: a case-control study in a low-incidence population. Gynecol Oncol 2003;89:318–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riman T, Dickman PW, Nilsson S, Correia N, Nordlinder H, Magnusson CM, Persson IR. Risk factors for epithelial borderline ovarian tumors: results of a Swedish case-control study. Gynecol Oncol 2001;83:575–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greggi S, Parazzini F, Paratore MP, Chatenoud L, Legge F, Mancuso S, La Vecchia C. Risk factors for ovarian cancer in central Italy. Gynecol Oncol 2000;79:50–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ness RB, Grisso JA, Klapper J, Schlesselman JJ, Silberzweig S, Vergona R, Morgan M, Wheeler JE. Risk of ovarian cancer in relation to estrogen and progestin dose and use characteristics of oral contraceptives. SHARE Study Group. Steroid Hormones and Reproductions. Am J Epidemiol 2000;152:233–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salazar-Martinez E, Lazcano-Ponce EC, Gonzalez LG, Escudero-De LRP, Salmeron-Castro J, Hernandez-Avila M. Reproductive factors of ovarian and endometrial cancer risk in a high fertility population in Mexico. Cancer Res 1999;59:3658–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirose K, Tajima K, Hamajima N, Kuroishi T, Kuzuya K, Miura S, Tokudome S. Comparative case-referent study of risk factors among hormone-related female cancers in Japan. Jpn J Cancer Res 1999;90:255–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori M, Nishida T, Sugiyama T, Komai K, Yakushiji M, Fukuda K, Tanaka T, Yokoyama M, Sugimori H. Anthropometric and other risk factors for ovarian cancer in a case-control study. Jpn J Cancer Res 1998;89:246–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siskind V, Green A, Bain C, Purdie D. Breastfeeding, menopause, and epithelial ovarian cancer. Epidemiology 1997;8:188–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenblatt KA, Thomas DB. Lactation and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. The WHO Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid Contraceptives. Int J Epidemiol 1993;22:192–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y, Wu PC, Lang JH, Ge WJ, Hartge P, Brinton LA. Risk factors for epithelial ovarian cancer in Beijing, China. Int J Epidemiol 1992;21:23–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gwinn ML, Lee NC, Rhodes PH, Layde PM, Rubin GL. Pregnancy, breast feeding, and oral contraceptives and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Epidemiol 1990;43:559–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Booth M, Beral V, Smith P. Risk factors for ovarian cancer: a case-control study. Br J Cancer 1989;60:592–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hartge P, Schiffman MH, Hoover R, McGowan L, Lesher L, Norris HJ. A case-control study of epithelial ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;161:10–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mori M, Harabuchi I, Miyake H, Casagrande JT, Henderson BE, Ross RK. Reproductive, genetic, and dietary risk factors for ovarian cancer. Am J Epidemiol 1988;128:771–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cramer DW, Hutchison GB, Welch WR, Scully RE, Ryan KJ. Determinants of ovarian cancer risk. I. Reproductive experiences and family history. J Natl Cancer Inst 1983;71:711–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang M, Xie X, Lee AH, Binns CW. Prolonged lactation reduces ovarian cancer risk in Chinese women. Eur J Cancer Prev 2004;13:499–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riman T, Dickman PW, Nilsson S, Correia N, Nordlinder H, Magnusson CM, Persson IR. Risk factors for invasive epithelial ovarian cancer: results from a Swedish case-control study. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156:363–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harlow BL, Weiss NS, Roth GJ, Chu J, Daling JR. Case-control study of borderline ovarian tumors: reproductive history and exposure to exogenous female hormones. Cancer Res 1988;48:5849–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Risch HA, Weiss NS, Lyon JL, Daling JR, Liff JM. Events of reproductive life and the incidence of epithelial ovarian cancer. Am J Epidemiol 1983;117:128–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Modugno F, Ness RB, Wheeler JE. Reproductive risk factors for epithelial ovarian cancer according to histologic type and invasiveness. Ann Epidemiol 2001;11:568–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Purdie DM, Siskind V, Bain CJ, Webb PM, Green AC. Reproduction-related risk factors for mucinous and nonmucinous epithelial ovarian cancer. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:860–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu QJ, Yang Y, Vogtmann E, Wang J, Han LH, Li HL, Xiang YB. Cruciferous vegetables intake and the risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Oncol 2013;24:1079–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (cited 3 May 2013)

- 54.Jüni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 1999;282:1054–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greenland S. Invited commentary: a critical look at some popular meta-analytic methods. Am J Epidemiol 1994;140:290–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamling J, Lee P, Weitkunat R, Ambuhl M. Facilitating meta-analyses by deriving relative effect and precision estimates for alternative comparisons from a set of estimates presented by exposure level or disease category. Stat Med 2008;27:954–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greenland S, Longnecker MP. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:1301–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Orsini N, Li R, Wolk A, Khudyakov P, Spiegelman D. Meta-analysis for linear and nonlinear dose-response relations: examples, an evaluation of approximations, and software. Am J Epidemiol 2012;175:66–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tung KH, Wilkens LR, Wu AH, McDuffie K, Nomura AM, Kolonel LN, Terada KY, Goodman MT. Effect of anovulation factors on pre- and postmenopausal ovarian cancer risk: revisiting the incessant ovulation hypothesis. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:321–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wojcicki JM. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:341–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soto-Ramírez N, Karmaus W. The use of oral contraceptive before pregnancy and breastfeeding duration: a cross-sectional study with retrospective ascertainment. Int Breastfeed J 2008;3:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Giglia R, Binns CW, Alfonso H. Maternal cigarette smoking and breastfeeding duration. Acta Paediatr 2006;95:1370–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child and Human Development. National Institutes of Health. Available from http://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/breastfeeding/Pages/default.aspx (cited 18 January 2013)