Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to estimate the prevalence and time trends in prescriptions of methylphenidate, dexamphetamine, and atomoxetine in children and adolescents, within three diagnostic groups: 1) autism spectrum disorder (ASD), 2) attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and 3) other psychiatric disorders.

Methods

Data from six different national registers were used and merged to identify a cohort of all children and adolescents born in Denmark between 1990 and 2001 (n=852,711). Sociodemographic covariates on cohort members and their parents and lifetime prescriptions of methylphenidate, dexamphetamine, and atomoxetine were extracted from the registers. Prescriptions were also stratified by duration (<6 months. vs.≥6 months).

Results

Sixteen percent of 9698 children and adolescents with ASD (n=1577), 61% of 11,553 children and adolescents with ADHD (n=7021) and 3% of 48,468 children and adolescents with other psychiatric disorders (n=1537) were treated with one or more ADHD medications. There was a significant increase in prescription rates of these medications for all three groups. From 2003 to 2010, youth 6–13 years of age with ASD, ADHD, and other psychiatric disorders had 4.7-fold (4.4–4.9), 6.3-fold (6.0–6.4), and 5.5-fold (5.0–5.9) increases, respectively, in prescription rates of ADHD medications.

Conclusion

This is the largest study to date assessing stimulant treatment in children and adolescents with ASD, and is the first prospective study quantifying the change over time in the prevalence of treatment with ADHD medications in a population-based national cohort of children and adolescents with ASD. The prevalence of stimulant treatment in youth with ASD of 16% is consistent with earlier studies. The past decade has witnessed a clear and progressive increase in the prescription rates of medications typically used to treat ADHD in children and adolescents in Denmark. This increase is not limited to only those with ADHD, but includes others with neuropsychiatric disorders, including ASD. The risks and benefits of this practice await further study.

Introduction

Prescription rates of stimulants and other pharmacological agents for treating patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have increased tremendously over the last decade (Bruckner et al. 2012). This increase has been noted worldwide, but the largest increase has been in some areas of the United States, where up to 5% of school-aged children are prescribed medications for ADHD (Zuvekas et al. 2006; Castle et al. 2007; Oswald and Sonenklar 2007,). Although the use of ADHD medications is generally lower in the European countries than in the United States, the same trend with increased number of prescriptions has been documented in The Netherlands, Denmark, and Spain (Hodgkins et al. 2011; Pottegard et al. 2012; Treceno et al. 2012).

In addition, clinicians are now increasingly prescribing these medications to treat children with other psychiatric disorders. For example, in clinical samples, 30–85 % of children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD) also exhibit some of the core symptoms of ADHD; namely, hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity (Rommelse et al. 2010). Some of the first reports on the use of Benzedrine reported benefits in children with a variety of psychiatric diagnoses (Bradley 1937). Clinicians face the challenge of treating these impairing symptoms, and there is some evidence to suggest that psychostimulants can be efficacious in the short-term treatment of ADHD-like symptoms, particularly symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity in individuals with ASD (Aman and Langworthy 2000; Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology [RUPP] Autistic Disorder Network 2005; Posey et al. 2007; Aman et al. 2008). Previous studies on the prevalence of ADHD medication in clinical samples of children with ASD have been limited by small sample size (Martin et al. 1999; Frazier et al. 2011; Memari et al. 2012) or significant selection bias and the use of unvalidated parent-reported diagnoses in online surveys (Witwer and Lecavalier 2005; Green et al. 2006; Rosenberg et al. 2010). The present study is the first population-based study to report on the prevalence of stimulant treatment in children and adolescents with ASD and the change in prevalence over time. The objective of the study is to describe 10 year trends in ADHD medication prescriptions for children and adolescents with ADHD, ASD, and other psychiatric disorders, using national registry data.

Methods

This study utilizes data from a number of nationwide Danish registers using the unique personal identification number as a key identifier to combine data across a number of national registers.

Participants

Data from the Danish Civil Registration System (CRS) (Pedersen et al. 2006) was used to identify a cohort of all children and adolescents born in Denmark between 1990 and 2001 (n=852,711) and their parents. All of the subjects in this cohort were followed prospectively from birth until date of death or December 31, 2010, whichever came first. Within this birth cohort, we identified all who had received any psychiatric International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10) (World Health Organization 1993) clinical diagnosis (any F-diagnosis) in either the Danish Psychiatric Central Register (DPCR) (Munk-Jorgensen and Mortensen 1997) or the Danish National Hospital Register (DNHR) before December 31, 2010. Based on these data, we defined three mutually exclusive groups of patients: 1) ADHD (may have been diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders, but never ASD), 2) ASD (may also have been given a diagnosis of ADHD or other psychiatric disorders at some point), and 3) Other psychiatric disorders (never ADHD or ASD). All major and comorbid diagnoses were included. Group 1) ADHD (n=11,553) included the ICD-10 codes F90.0, F90.1, F90.8, or F90.9 (hyperkinetic disorder), group 2) ASD (n=9698) included the codes F84.0, F84.1, F84.8, or F84.9 (pervasive developmental disorder) and group 3) other psychiatric disorders (n=48,468) included codes for any other F-diagnoses.

Data on prescriptions

For all participants in the three study groups, data on prescriptions for all drug purchases recorded in the Danish Register of Medical Product Statistics (DRMPS) were included in the data set. Data on prescriptions for each proband were included from the birth of the subject until date of that person's death, or December 31, 2010, whichever came first. For this study, ADHD pharmacological treatment was defined as purchase of a drug containing dexamphetamine (anatomical therapeutic chemical [ATC]-code N06BA02), methylphenidate (N06BA04), or atomoxetine (N06BA09).

Baseline characteristics of the study population

Data on baseline variables measured at the time of the subject's birth included early measures of perinatal and child health (e.g., length of gestation, birth complications, birth weight, 5 min Apgar score, number of injuries before the age of 5). We also ascertained the presence of comorbid psychiatric disorders and mental retardation. The baseline characteristics of the subjects included in this study are shown in Table 1. The study also includes data concerning any psychiatric diagnoses in parents, and parental age.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Three Study Groups (Mutually Exclusive): Youth with ADHD, ASD and Other Psychiatric Disorders

| |

ADHD diagnosis |

ASD diagnosis |

Other psychiatric diagnosesa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

(n=11,553) |

(n=9,698) |

(n=48,468) |

|||

| Variableb | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Child: | ||||||

| Gender (male) | 8,961 | 78% | 7,727 | 80% | 24,425 | 50.4% |

| Gestation length (weeks)c | 39.3 | (2.3) | 39.5 | (2.1) | 39.4 | (2.1) |

| 5-minute Apgar scorec | 9.78 | (1.0) | 9.78 | (1.0) | 9.78 | (1.0) |

| Birth weight | ||||||

| Less than 1,500 g | 167 | 1.5% | 106 | 1.1% | 513 | 1.1% |

| 1,500–2,500 g | 679 | 6.2% | 482 | 5.2% | 2,591 | 5.7% |

| Above 2,500 g | 10,181 | 92.3% | 8,667 | 93.7% | 42,748 | 93.2% |

| Complications at birth | 2,754 | 23.8% | 2.598 | 26.8% | 7,996 | 16.5% |

| Mental retardation | 568 | 4.9% | 1,256 | 13.0% | 2,020 | 4.2% |

| Number of psychiatric disordersc | 2.3 | (4.3) | 2.8 | (4.3) | 2.8 | (3.9) |

| Number of injuries before age 5c | 1.0 | (1.5) | 0.8 | (1.3) | 0.7 | (1.2) |

| Parents: | ||||||

| Mother's age at childbirthc | 27.9 | (5.2) | 29.3 | (5.0) | 28.4 | (5.1) |

| Father's age at childbirthc | 30.9 | (6.1) | 32.3 | (6.2) | 31.4 | (6.1) |

| Mother any psychiatric diagnoses | 1087 | 9.4% | 691 | 7.1% | 3,745 | 7.7% |

| Father any psychiatric diagnoses | 893 | 8.2% | 557 | 6.0% | 2,745 | 5.9% |

Any psychiatric diagnoses, but never ADHD or ASD.

Baseline characteristics measured at child birth.

Mean and (standard deviation).

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; ns, non-significantly different.

Statistics

Descriptive analyses were performed for each of the three diagnostic groups (ADHD, ASD, and other psychiatric disorders) on the prevalence of ADHD medication for each of the 12 birth cohorts (1990–2001) separately, in 1 year age bands. For each 1 year age band from age 4 to 20 years, the prevalence of ADHD medication in one birth cohort was compared with the preceding birth cohort. By collapsing the birth cohorts and dividing cohort members into three different groups (age 6–9, age 10–13, and age 14–17) the article also includes descriptive analyses of prevalence in calendar time; that is, yearly point prevalence of ADHD medication during the period 1999–2010 for each of the three diagnostic groups. The yearly prevalence was calculated by dividing the summed number of youth treated with the total number of youth in the cohort, each year. Test of differences in prevalence between one age cohort and the previous cohort, tests of mean differences in the prevalence of ADHD medications among the three diagnostic groups, and mean differences in doses among the three diagnostic groups were calculated using ANOVA F test, applying a 5% significance level. In testing for group differences, the likelihoods of ADHD treatment odds ratios (OR) were calculated, with 95 % confidence intervals. The statistical package SAS 9.2 was used in the analyses (SAS Institute Inc. 2000). The study was approved by the Danish Psychiatric Central Register (7-505-29-1470/1) and by the Danish Data Protection Agency (2010-41-4766).

Results

In the total sample of 852,711 born between 1990 and 2001 in Denmark, 13,312 children and adolescents had received ADHD medication for at least 6 months prior to 2010. This corresponds to a total population prevalence rate of 1.56 % in those 0–20 years of age. The mean age at initiation of treatment in this group was 11.90 years (SD=3.35). A total of 69,719 children and adolescents had a clinical diagnosis of ADHD, ASD, or another psychiatric disorder (corresponding to an 8.2 % prevalence of psychiatric disorders), and 14.5 % of them had received ADHD medication for at least 6 months.

Children and adolescents with ADHD were more likely to be treated with methylphenidate, dexamphetamine, or atomoxetine than were those with ASD (OR=8.0; 7.5–8.5) or another psychiatric disorder (OR=47.3; 44.4–50.4).

The distribution of the other psychiatric disorders (not ADHD or ASD) in children and adolescents in treatment with ADHD medication is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of Other Psychiatric Disorders in Youth in Treatment with ADHD Medicationa

| n | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Other behavioral and emotional disorders in childhood | 353 | 23.0 |

| Other psychiatric disorders | 333 | 21.7 |

| Anxiety disorders | 229 | 14.9 |

| Other developmental disorders | 176 | 11.5 |

| Tic disorders | 126 | 8.2 |

| ODD/CD | 115 | 7.5 |

| Substance use disorder | 102 | 6.6 |

| Attachment disorders | 59 | 3.8 |

| Affective disorder | 44 | 2.9 |

| 1537 | 100.0 |

Methylphenidate, dexamphetamine and/or atomoxetine.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD/CD, oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder.

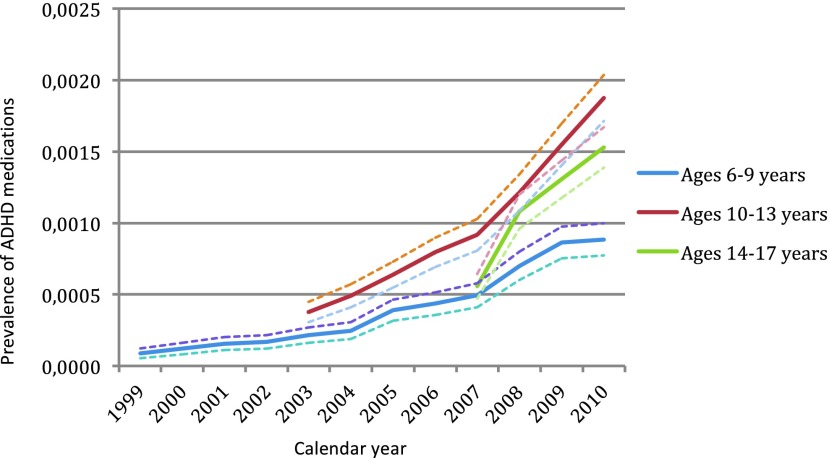

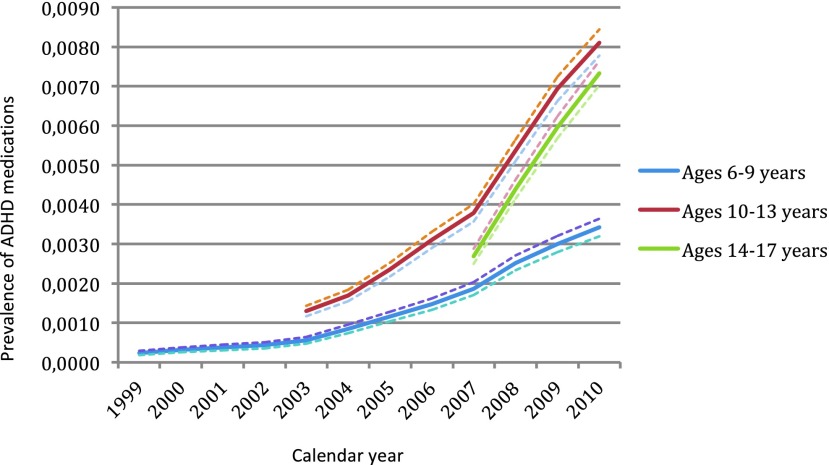

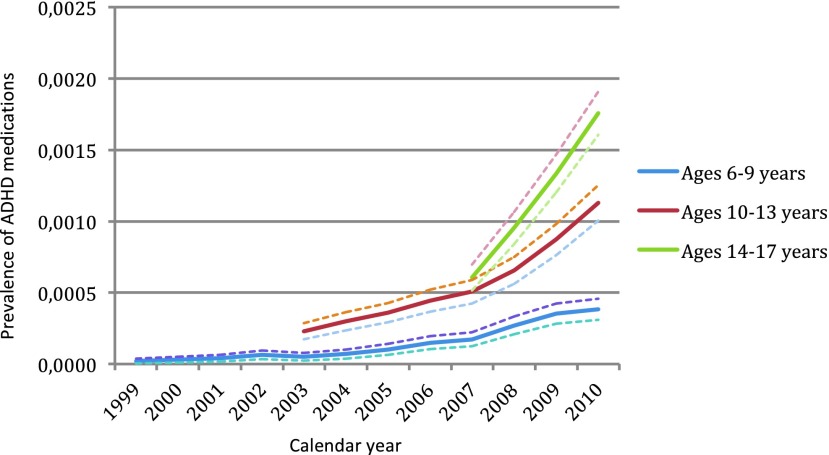

The highest prevalence of ADHD medication in those with ADHD and ASD was found in the age group 10–13 years. In youth with other psychiatric disorders, the highest prevalence of ADHD medication was found in the age group 14–17 years. The prevalence of treatment with ADHD medications among the three different diagnostic groups over time is shown in Figure 1 (ASD), Figure 2 (ADHD), and Figure 3 (other psychiatric disorders), divided into three age groups (age 6–9, age 10–13, and age 14–17).

FIG. 1.

Prevalence of treatment with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medication (methylphenidate, dexamphetamine and/or atomoxetine) over time, in youth with autism spectrum disorder, with 95% confidence intervals. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD; autism spectrum disorder. A color version of this figure is available in the online article at www.liebertpub.com/jcap

FIG. 2.

Prevalence of treatment with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medication (methylphenidate, dexamphetamine and/or atomoxetine over time), in youth with ADHD, with 95% confidence intervals. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. A color version of this figure is available in the online article at www.liebertpub.com/jcap

FIG. 3.

Prevalence of treatment with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medication (methylphenidate, dexamphetamine and/or atomoxetine) over time, in youth with other psychiatric disorders, with 95% confidence intervals. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. A color version of this figure is available in the online article at www.liebertpub.com/jcap

In the total population, there was a 5.8-fold increase (5.6–5.9) in the number of children and adolescents ages 6–13, who were treated for at least 6 months with ADHD medications. From 2003 to 2010, youth ages 6–13 with ASD, ADHD, and other psychiatric disorders had a 4.7-fold (4.4–4.9), 6.3-fold (6.0–6.4), and 5.5-fold (5.0–5.9) increase in prescription rates of ADHD medications, respectively.

Medication in youth with ADHD

Within this cohort, 11,553 were diagnosed with ADHD. Of these, 61% (n=7021) were treated with ADHD medications, corresponding to a 0.82% prevalence of treatment in the total population. Table 3 shows the prevalence of ADHD medication for each birth cohort, divided into 1 year age bands. Throughout the observation period, there was an overall significant increase in propensity of ADHD treatment each year. During the last 2 or 3 years of observation, there was a significant increase each year as compared with the previous year in the majority of cohorts.

Table 3.

Percentage of Children and Adolescents with a Clinical Diagnosis of ADHD in Treatment with ADHD Medicationa (n=11,553)

| |

Age |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth cohort | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | All |

| 1990 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.57 |

| 1991 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.35 | - | 0.66 |

| 1992 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.44 | - | - | 0.77 |

| 1993 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.60 | - | - | - | 0.85 |

| 1994 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.73 | - | - | - | - | 0.90 |

| 1995 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.59 | 0.71 | 0.81 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.97 |

| 1996 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.70 | 0.80 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.93 |

| 1997 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.69 | 0.82 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.91 |

| 1998 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.49 | 0.70 | 0.81 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.92 |

| 1999 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.44 | 0.69 | 0.90 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.96 |

| 2000 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.71 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.76 |

| 2001 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0.64 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.65 |

| All cohorts | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.82 |

| F test | 2.02 | 5.70 | 11.56 | 37.98 | 73.29 | 119.45 | 128.25 | 148.06 | 116.04 | 116.96 | 111.47 | 106.55 | 90.96 | 56.82 | 19.82 | 4.41 | - | |

| p value | 0.027 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.036 | - | |

Bold letters indicate significantly different from the previous cohort (5% significance level).

Methylphenidate, dexamphetamine and/or atomoxetine.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Medication in youth with ASD and other psychiatric disorders

Of 9698 subjects diagnosed with ASD in this cohort, 16% were treated with ADHD medications, corresponding to a 0.18 % population prevalence of treatment (n=1577). Among 48,468 youth with other psychiatric disorders, 3% were treated with ADHD medication. Table 4 shows the prevalence of ADHD medication in subjects with ASD for each birth cohort, divided into 1 year age bands and Table 5 shows the prevalence of ADHD medication in subjects with other psychiatric disorders. There was a clear and significant overall increase in propensity of ADHD treatment in both groups (ASD and other psychiatric disorders) throughout the observation period for each birth cohort, but the year-to-year increase was rarely statistically significant.

Table 4.

Percentage of Children and Adolescents with a Clinical Diagnosis of ASD in Treatment with ADHD Medicationa (n=9698)

| |

Age |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Cohort | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | All |

| 1990 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.10 |

| 1991 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | - | 0.13 |

| 1992 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 | - | - | 0.16 |

| 1993 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | - | - | - | 0.18 |

| 1994 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.17 | - | - | - | - | 0.24 |

| 1995 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.17 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.21 |

| 1996 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.19 |

| 1997 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.21 |

| 1998 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.22 |

| 1999 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.21 |

| 2000 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.21 |

| 2001 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.17 |

| All cohorts | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.18 |

| F test | 1.05 | 1.92 | 6.04 | 9.90 | 15.72 | 25.56 | 26.28 | 24.39 | 25.15 | 22.88 | 23.42 | 24.89 | 21.27 | 8.94 | 4.92 | 0.73 | - | |

| p value | 0.397 | 0.032 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.394 | - | |

Bold letters indicate significantly different from earlier cohort (5% significance level).

Methylphenidate, dexamphetamine and/or atomoxetine.

ASD, autism spectrum disorder; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Table 5.

Percentage of Children and Adolescents with Other Psychiatric Disordersa in Treatment with ADHD Medicationb (n=48,468)

| |

Age |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Cohort | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | All |

| 1990 | - | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.21 |

| 1991 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.14 | - | 0.24 |

| 1992 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.15 | - | - | 0.23 |

| 1993 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.19 | - | - | - | 0.25 |

| 1994 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.19 | - | - | - | - | 0.22 |

| 1995 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.17 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.21 |

| 1996 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.18 |

| 1997 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.16 |

| 1998 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.12 |

| 1999 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.12 |

| 2000 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.12 |

| 2001 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.08 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.09 |

| All cohorts | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.18 |

| F-test | - | 1.11 | 1.85 | 6.43 | 11.97 | 16.98 | 16.05 | 11.99 | 14.36 | 16.38 | 23.55 | 24.16 | 24.04 | 21.42 | 14.43 | 4.97 | - | |

| p value | - | 0.352 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.026 | - | |

Bold letters indicate significantly different from earlier cohort (5% significance level).

Not diagnosed with ADHD or ASD.

Methylphenidate, dexamphetamine and/or atomoxetine.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder.

Mean age at initiation of ADHD medication in subjects with ASD was 10.9 years (SD 3.0), significantly younger than the age of 11.6 years (SD 3.2) for subjects with ADHD (Z=17.1, p<0.0001), who in turn were significantly younger than those with other psychiatric disorders with a mean of 13.3 years (SD 3.5) (Z=33.4, p<0.0001).

Discussion

Overall, we found a clear increase in the prevalence of ADHD medication in youth with ADHD, ASD, and other psychiatric disorders over the past decade. The increase was highest in patients with ADHD, and we found a significant yearly increase during the last 3 years of our observations in the period from 2008 to 2010 in this group.

Sixty-one percent of the children and adolescents with a clinical diagnosis of ADHD were prescribed one or more of these medications during follow-up. This proportion is lower than in United States samples (Rowland et al. 2002; Sclar et al. 2012), but is similar to what has been reported in the Scandinavian countries (Zoega et al. 2011) and other European countries (Wittchen et al. 2011). We also found that 16% of youth with ASD were treated with ADHD medications. This is consistent with some of the previous studies estimating a prevalence of stimulant treatment of 14–33% of children with ASD (Martin et al. 1999; Rosenberg et al. 2010; Frazier et al. 2011; Memari et al. 2012). Martin et al. found that 20% of 109 children and adolescents with ASD from a clinical sample were treated with stimulants (Martin et al. 1999). Rosenberg et. al. assessed parent-reported diagnoses and pharmacological treatment and found that 15% of 5181 children diagnosed with ASD were treated with ADHD medications (Rosenberg et al. 2010). Although the sample size in the Rosenberg study came close to that in our study, the ascertainment procedures were quite different. The Rosenberg study assessed an online database, to which parents voluntarily report diagnoses and treatment, and the information provided in the database was not validated and participation may have been skewed and prone to selection bias. For example, parental reporting did require access to a computer and the Internet. In a study from Iran, Memari et al. assessed 345 children, validated the ASD diagnoses, and found that 14% were treated with stimulants. Witwer and Lecavalier recruited 353 children with parent-reported ASD and found that 24% had been treated with stimulants within the preceding 12 months (Witwer and Lecavalier 2005). In a smaller study of students in special education, Frazier et al. found that 33% of 290 children with ASD and ADHD received stimulant treatment compared with 44% of 520 children with ADHD without ASD, and 6% of children with ASD without ADHD. However, the study did not examine the change in prevalence of treatment over time (Frazier et al. 2011). In a study by Green et al., two ASD patient organizations distributed a web-based survey to parents (Green et al. 2006). Diagnoses were not validated, only children receiving at least one treatment were included, and >25% of the submitted surveys were excluded because of missing data. Of the included 552 children, 50% were given pharmacological treatment, but the prevalence of stimulant treatment was not reported. Population surveys in the field are often limited by large attrition rates of >50% (Aman et al. 2005).

Patients with ASD and impairing ADHD symptoms may be excluded from receiving adequate treatment in countries where reimbursement is based on the current American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) system, because ASD is an exclusion criterion when making a diagnosis of ADHD. In contrast, children with ASD and comorbid ADHD can have reimbursements in Denmark. In both ICD-10 and American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (DSM-IV), fulfilling criteria for ASD is an exclusion criterion for ADHD (American Psychiatric Association 1994). This criterion will most likely be changed with the fifth revision of the DSM, as ADHD is shown to be one of the most frequent comorbid conditions in children with PDD (American Psychiatric Association 2012; Dalsgaard 2012).

Despite a substantial increase in prescriptions of ADHD medications for children and adolescents in Denmark during the past 10 years, the prevalence of ADHD medication in the present study is lower than in many other Western countries. In Denmark, ADHD pharmacological treatments in youth can only be initiated by physicians authorized by The Danish Medical Board as specialists in child and adolescent psychiatry, psychiatry, paediatrics, or neurology (National Board of Health 2007, 2008). Youth can be assessed and treated by such a specialist either at a hospital department or in a private practice. General practitioners (GP's) can perform follow-up of these patients in shared-care models, but they are not licensed to initiate ADHD treatment. This may in part explain the lower prevalence of ADHD pharmacotherapy in Denmark found in the present study (Dalsgaard et al. 2012).

In this study, we have only examined the use of ADHD medications for the three groups of patients. Some of these patients may have been given other pharmacological agents.

In this nationwide sample, the overall prevalence of ADHD medication (treatment for at least 6 months) was 1.56%, which means that ∼ 50% of the children and adolescents with the disorder are currently treated in Denmark, as the estimated prevalence of ADHD is 3–5%, according to DSM-IV. There has been a tremendous increase worldwide in the number of children given ADHD medication, as our study also shows.

We found that the highest prevalence of ADHD medication in children with ADHD was in the group 10–13 years of age. This is most likely because children from the earlier cohorts are diagnosed later than the ones from later cohorts. In the mid 1990s, fewer were diagnosed, especially adolescents, and the ones from the earlier cohorts with ADHD were diagnosed later.

We also found significant age differences among the three diagnostic groups, with children with ASD starting pharmacological treatment for ADHD symptoms at a younger age than children with ADHD without ASD. Children with psychiatric disorders other than ADHD and ASD were significantly older when treated than were those in the two other groups. These age differences most likely reflect the fact that symptoms of ASD emerge at a very young age, symptoms of ADHD emerge a little later, and the other psychiatric disorders are less specific and, therefore, are referred for psychiatric assessment when the patient is older.

As with other registry-based studies, our study has limitations. Diagnoses in the registers are clinical diagnoses, not the result of a systematic well-described uniform psychiatric assessment.

Conclusion

This is the first population-based study to report on the increase in prevalence of stimulant treatment in children and adolescents with ASD, ADHD, and other psychiatric disorders. We show that there has been an almost fourfold increase in prescription rates of ADHD medications, specifically for children and adolescents with ASD, in Denmark over the past decade, and that 16% of all youth with a clinical diagnosis of ASD were treated with ADHD medications in 2010. This prevalence is comparable to the lower prevalence found in previous smaller studies. The population prevalence of children and adolescents treated with ADHD medications for at least 6 months was 1.56% in 2010.

Clinical Significance

The increasing prescription rates of ADHD medications for youth with ASD should be viewed in context of the limited evidence for efficacy in this population of patients. This underscores the need for future research examining the safety and long-term benefits of stimulant medication among children and adolescents with ASD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Niels Gregersen for help with data management, Hanne Birgitte Hede Jørgensen at the Centre for Register-based Research for the proofreading of the manuscript, and James F. Leckman for help in revising an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Disclosures

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Aman MG. Farmer CA. Hollway J. Arnold LE. Treatment of inattention, overactivity, and impulsiveness in autism spectrum disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17:713–738. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.06.009. vii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG. Lam KS. Van Bourgondien ME. Medication patterns in patients with autism: temporal, regional, and demographic influences. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:116–126. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG. Langworthy KS. Pharmacotherapy for hyperactivity in children with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30:451–459. doi: 10.1023/a:1005559725475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic, Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Development: ADHD and Disruptive Behavior Disorders. http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=3832012. [Nov 17;2012 ]. http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=3832012

- Bradley C. The behavior of children recieving Benzedrine. J Psychiatry. 1937;94:577–585. [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner TA. Hodgson A. Mahoney CB. Fulton BD. Levine P. Scheffler RM. Health care supply and county-level variation in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder prescription medications. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:442–449. doi: 10.1002/pds.2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle L. Aubert RE. Verbrugge RR. Khalid M. Epstein RS. Trends in medication treatment for ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2007;10:335–342. doi: 10.1177/1087054707299597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard S. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;22:43–48. doi: 10.1007/s00787-012-0277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard S. Humlum MK. Nielsen HS. Simonsen M. Relative standards in ADHD diagnoses: The role of specialist behavior. Econ. Letters. 2012;117:663–665. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier TW. Shattuck PT. Narendorf SC. Cooper BP. Wagner M. Spitznagel EL. Prevalence and correlates of psychotropic medication use in adolescents with an autism spectrum disorder with and without caregiver-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21:571–579. doi: 10.1089/cap.2011.0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green VA. Pituch KA. Itchon J. Choi A. O'Reilly M. Sigafoos J. Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autism. Res Dev Disabil. 2006;27:70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkins P. Sasane R. Meijer WM. Pharmacologic treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children: Incidence, prevalence, and treatment patterns in the Netherlands. Clin Ther. 2011;33:188–203. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. Scahill L. Klin A. Volkmar FR. Higher-functioning pervasive developmental disorders: rates and patterns of psychotropic drug use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:923–931. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memari AH. Ziaee V. Beygi S. Moshayedi P. Mirfazeli FS. Overuse of psychotropic medications among children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: Perspective from a developing country. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk–Jorgensen P. Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Register. Dan Med Bull. 1997;44:82–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Board of Health: Clinical guidelines for pharmacological treatment of children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders [in Danish] Copenhagen: National Board of Health [Sundhedsstyrelsen]; 2007. VEJ nr 10332 af 10/12/2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Board of Health: Clinical guidelines for the prescription of classified drugs [in Danish] Copenhagen: National Board of Health [Sundhedsstyrelsen]; 2008. VEJ nr 38 af 18/06/2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oswald DP. Sonenklar NA. Medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17:348–355. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.17303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CB. Gotzsche H. Moller JO. Mortensen PB. The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull. 2006;53:441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posey DJ. Aman MG. McCracken JT. Scahill L. Tierney E. Arnold LE. Vitiello B. Chuang SZ. Davies M. Ramadan Y. Witwer AN. Swiezy NB. Cronin P. Shah B. Carroll DH. Young C. Wheeler C. McDougle CJ. Positive effects of methylphenidate on inattention and hyperactivity in pervasive developmental disorders: An analysis of secondary measures. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottegard A. Bjerregaard BK. Glintborg D. Hallas J. Moreno SI. The use of medication against attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Denmark: A drug use study from a national perspective. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:1443–1450. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1265-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autistic Disorder Network: Randomized, controlled, crossover trial of methylphenidate in pervasive developmental disorders with hyperactivity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1266–1274. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rommelse NN. Franke B. Geurts HM. Hartman CA. Buitelaar JK. Shared heritability of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19:281–295. doi: 10.1007/s00787-010-0092-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg RE. Mandell DS. Farmer JE. Law JK. Marvin AR. Law PA. Psychotropic medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders enrolled in a national registry, 2007–2008. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:342–351. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0878-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland AS. Umbach DM. Stallone L. Naftel AJ. Bohlig EM. Sandler DP. Prevalence of medication treatment for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder among elementary school children in Johnston County, North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:231–234. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2000. SAS (release 9.2) [Google Scholar]

- Sclar DA. Robison LM. Bowen KA. Schmidt JM. Castillo LV. Oganov AM. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children and adolescents in the United States: Trend in diagnosis and use of pharmacotherapy by gender. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012;51:584–589. doi: 10.1177/0009922812439621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treceno C. Martin Arias LH. Sainz M. Salado I. Garcia Ortega P. Velasco V. Jimeno N. Escudero A. Velasco A. Carvajal A. Trends in the consumption of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medications in Castilla y Leon (Spain): Changes in the consumption pattern following the introduction of extended release methylphenidate. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:435–441. doi: 10.1002/pds.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU. Jacobi F. Rehm J. Gustavsson A. Svensson M. Jonsson B. Olesen J. Allgulander C. Alonso J. Faravelli C. Fratiglioni L. Jennum P. Lieb R. Maercker A. van Os J. Preisig M. Salvador–Carulla L. Simon R. Steinhausen HC. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:655–679. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witwer A. Lecavalier L. Treatment incidence, patterns in children, adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:671–681. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. [Google Scholar]

- Zoega H. Furu K. Halldorsson M. Thomsen PH. Sourander A. Martikainen JE. Use of ADHD drugs in the Nordic countries: a population-based comparison study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123:360–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuvekas SH. Vitiello B. Norquist GS. Recent trends in stimulant medication use among U.S. children. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:579–585. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]