Abstract

Background

Cilengitide, an αv integrin antagonist, has demonstrated activity in recurrent adult glioblastoma (GBM). The Children's Oncology Group ACNS0621 study thus evaluated whether cilengitide is active as a single agent in the treatment of children with refractory high-grade glioma (HGG). Secondary objectives were to investigate the pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenomics of cilengitide in this population.

Methods

Cilengitide (1800 mg/m2/dose intravenous) was administered twice weekly until evidence of disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Thirty patients (age range, 1.1–20.3 years) were enrolled, of whom 24 were evaluable for the primary response end point.

Results

Toxicity was infrequent and mild, with the exception of one episode of grade 2 pain possibly related to cilengitide. Two intratumoral hemorrhages were reported, but only one (grade 2) was deemed to be possibly related to cilengitide and was in the context of disease progression. One patient with GBM received cilengitide for 20 months and remains alive with continuous stable disease. There were no other responders, with median time to tumor progression of 28 days (range, 11–114 days). Twenty-one of the 24 evaluable patients died, with a median time from enrollment to death of 172 days (range, 28–325 days). The 3 patients alive at the time of this report had a follow-up time of 37, 223, and 1068 days, respectively.

Conclusions

We conclude that cilengitide is not effective as a single agent for refractory pediatric HGG. However, further study evaluating combination therapy with cilengitide is warranted before a role for cilengitide in the treatment of pediatric HGG can be excluded.

Keywords: childhood, cilengitide, high-grade glioma

Pediatric high-grade gliomas (pHGGs), including glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) and anaplastic astrocytoma (AA), typically have a dismal prognosis. The 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) rates reported from the Children's Cancer Group (CCG)-945 phase III study, which compared the outcomes in children with newly diagnosed pHGG randomized to receive treatment with radiation and chemotherapy consisting of either prednisone, lomustine, and vincristine (pCV) or the 8-in-1 drug regimen, were 23% for AA and 16% for GBM, with no statistical difference between treatment arms.1 Most recently, the Children's Oncology Group (COG) ACNS0126 study, a phase II trial of radiation and concurrent temozolomide followed by adjuvant temozolomide in newly diagnosed pHGG, found no improvement in the 3-year event-free survival (EFS) rate, compared with that previously reported in the CCG-945 study.2

The lack of success in the treatment of pHGG is multifactorial but is believed to be attributable in part to the limited drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier coupled with inherent tumor resistance to radiation and chemotherapy.3,4 Thus, targeting tumor-associated angiogenesis, a distinguishing feature of HGG, has become a major focus of clinical investigation in the treatment of this disease because of the potential for this strategy to circumvent these principal mechanisms of resistance. Integrins are the primary cell adhesion molecules that integrate angiogenic signals between the extracellular matrix (ECM) and intracellular signaling pathways.5 In particular, αv integrins mediate signaling through binding the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence in their respective ECM substrates.5,6 It has been demonstrated that appropriate ligation of the integrin αvβ3, which is selectively expressed on neo-endothelium, is important for sustaining angiogenesis.5,6 GBMs strongly express αv integrins and their ECM ligands.6,7 Cilengitide, a cyclic pentapeptide (cyclic-RGD) antagonist of the integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5, successfully blocks angiogenesis and induces the regression of orthotopic GBM in vivo.8–10 In clinical trials, cilengitide has demonstrated activity as a single agent in recurrent adult GBM11–14 and in a phase I pediatric study of refractory CNS tumors.15 Therefore, the COG ACNS0621 phase II study was conducted to evaluate whether cilengitide is active as a single agent in the treatment of children with refractory pHGG.

Materials and Methods

Eligibility

Patients <22 years of age were eligible if the institutional pathologist diagnosed a GBM, AA, anaplastic oligodendroglioma, high-grade astrocytoma NOS (anaplastic ganglioglioma, anaplastic mixed glioma, anaplastic mixed glioneuronal tumors), or gliosarcoma that was recurrent or progressive and refractory to standard therapy (generally considered as local irradiation and alkylator-based chemotherapy or chemotherapy alone if <3 years of age) and had radiographically documented measurable disease. Patients <3 years of age initially treated with chemotherapy alone could have been treated with radiation at time of first relapse. Patients with pontine gliomas, gliomatosis cerebri, primary spinal cord high-grade glioma, or evidence of prior CNS bleed were not eligible. Patients could not have had >2 prior treatments (1 initial and 1 for relapse) and had to have recovered from all prior therapy, with adequate organ function and a performance status of 0, 1, or 2. Centralized rapid neuroradiology and retrospective neuropathology reviews were requested for all patients. All centers had institutional review board approval prior to enrolling subjects, and all subjects were registered on-study after informed consent was obtained.

Treatment

Cilengitide was administered at 1800 mg/m2/dose (maximum 75 mg/kg) by 1-h intravenous (IV) infusion once per day on a twice per week schedule (with at least 2 days between doses). Twenty-eight consecutive days constituted one cycle, and subsequent cycles followed immediately with no break in study drug administration, provided the laboratory criteria for continuing were met (absolute neutrophil count, ≥ 1000 neutrophils/μL, platelet count,≥100 000 platelets/μL). Treatment was continued in the absence of disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Evaluation of Toxicity

Patients were assessed at baseline, prior to the start of each cycle, and at the time of removal from protocol by physical examination and laboratory evaluation of blood samples, serum chemistries, renal and liver function, and pregnancy tests. Medical history, neurological examination, and performance status were obtained at baseline and at the time of removal from therapy. Tibial growth plate evaluation by X-ray was performed at baseline and every 12 weeks during protocol therapy.

Evaluation of Response and Off-Protocol and Off-Study Criteria

Baseline MRI was obtained within 2 weeks after enrollment, and the start of treatment was within 5 days after enrollment. For the response assessment of target lesions, MRI scans were obtained 4 weeks after the start of treatment (prior to cycle 2) and compared with the baseline pretreatment MRI scan. Subsequent MRI scans after week 4 were obtained every 12 weeks thereafter. All subsequent scans used the MRI obtained at week 4 for comparison except in cases of progressive disease, in which the reference scan was the MRI with the smallest product observed since the start of treatment. Tumor response was determined by the changes in size with use of the maximal 2-dimensional cross-sectional tumor measurements, using either T1- or T2-weighted images (whichever gave the best estimate of tumor size). The tumor response definitions used were as follows: complete response (CR), disappearance of all target lesions; partial response (PR), ≥50% decrease in size of all target lesions; progressive disease (PD), ≥25% increase in the size of any target lesion or the appearance of new lesions; and stable disease (SD), neither sufficient decrease nor increase in tumor size to qualify for PR or PD, respectively. The initial MRI obtained after 4 weeks of treatment (after cycle 1) was compared with the baseline pretreatment MRI to establish the initial response to treatment (PD, SD, PR, or CR). Subsequent MRI scans were then compared with the post-cycle 1 MRI to confirm the duration of the initial response to 4 weeks of treatment. An initial response of SD, PR, or CR at 4 weeks was only declared to be a true objective response if it was sustained for 4 weeks for CR/PR and 12 weeks for SD. Because SD at 4 weeks is equivalent to the baseline MRI, subsequent MRIs would essentially be compared with either the baseline MRI or to the best initial response if CR/PR, for the determination of tumor response status. If the response showed a CR or PR at any time, the MRI was repeated 4 weeks later to document a sustained CR/PR. For confirmation of SD, the response had to be sustained for at least 12 weeks after the initial SD response assessment. Rapid central review was performed to confirm institutional reporting for all neuroimaging during the first 16 weeks of treatment, because this was the critical period during which success (CR/PR/SD) or failure (PD) of the drug was decided. The central review served as the definitive outcome for response reporting. A patient with documented PD could continue to receive cilengitide if all of the following criteria were met: the tumor had increased in size by 25%–50% from baseline, there were no new lesions, no other palliative anticancer chemotherapy was administered, and the patient had stable neurologic status. Patients who were removed from the study owing to early death or clinical progression prior to their initial MRI evaluation at 4 weeks were not considered to be evaluable for objective response because the protocol definition of PD was based solely on imaging changes, with no consideration of clinical progression. The rationale for these strict imaging criteria is that such early events prior to the patient having had prolonged drug exposure may reflect the natural course of the disease in its accelerated and terminal phase at study entry and are not an accurate measurement of the efficacy, or lack thereof, of the study drug, especially in the case of a cytostatic agent. A life expectancy of at least 8 weeks at the time of study entry was required to allow for this initial assessment of response to treatment to be made.

Patients were removed from protocol therapy in the event of unacceptable toxicity, refusal by patient or parent to continue, development of a second malignancy, or PD with >50% increase in tumor size and/or new lesions or PD with 25%–50% increase in tumor size and if the treating physician felt that it was not in the patient's best interest to continue cilengitide. Patients were declared off-study for death, loss to follow-up, patient enrollment in another COG study with tumor therapeutic intent (eg, at recurrence), withdrawal of consent for any further data submission, or the fifth anniversary of study entry.

Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacogenetic Analysis

The pharmacokinetic sampling strategy was based on an optimal limited-sampling scheme proposed from analysis of the pediatric phase I trial.15 On day 1 of course 1, blood samples for cilengitide were drawn before the first 60-min IV infusion and at 1, 3, and 6h after the end of infusion. Samples were collected in heparinized tubes and centrifuged, and the plasma was stored at −80°C until analysis. Aliquots of plasma were prepared for analysis with use of solid-phase extraction, and cilengitide concentrations were assayed using an isocratic high-performance liquid chromatography method with tandem mass spectrometer (LC-MS/MS).16 Cilengitide concentration-time data were modeled by a 2-compartment model using a maximum a priori algorithm as implemented in ADAPT V.17 Estimated parameters included central compartment volume (Vc), elimination rate constant (ke), and intercompartmental rate constants (k12 and k21). Bayesian priors (mean values and covariance matrix) for V, ke, k12, and k21 were established using the final distribution of estimated parameters in the earlier phase I trial. The estimated area under the concentration-time curve (AUC0-∞) for each patient was calculated as the dose divided by the Bayesian estimate of the clearance (D/Cl). For genotyping studies, polymorphisms at ABCB1 and ABCG2 were analyzed using the SNaPshot method (SNaPshot Multiplex System, Applied Biosystems, CA) with use of genomic DNA extracted from peripheral whole blood.

Statistical Considerations

The primary objective was to determine the objective response rate to cilengitide. Because of the natural history of pHGG and the cytostatic nature of cilengitide, successes for objective response included a confirmed CR/PR or SD that was sustained for at least 12 weeks, if the patient was receiving a stable or decreasing dose of corticosteroids. Patients discontinued from therapy for reasons other than PD or toxicity before response could be determined were considered to be inevaluable for response and were replaced. Patients discontinued from therapy because of toxicity before response could be determined were considered to be nonresponders. A response rate of 25% was considered to be beneficial for pHGG. The study used a 2-stage 5% vs 25% optimal design, which enrolled 9 evaluable patients during the first stage and proceeded to the second stage if there were ≥1 responders in the first stage for up to 24 evaluable patients in total. Altogether, ≥3 responses among 24 evaluable patients were needed to consider the trial to be successful. The alpha level (probability of concluding efficacy when response rate is 5%) of the design was 0.09, and the power (probability of concluding efficacy when response rate was 25%) was 0.9.

The secondary objectives were to estimate EFS (event included tumor progression or recurrence, second malignant neoplasm, or death), overall survival (OS; event included death owing to any cause), and the rate of toxicity, especially that of symptomatic intratumoral hemorrhage (ITH). These survival distributions were analyzed separately using the product-limit (Kaplan-Meier) estimator. Rates of individual toxicities, including symptomatic ITH, were summarized in each course of treatment with use of standard descriptive statistical methods. Patients were evaluable for toxicity for a particular cycle if the patients stayed on protocol through the end of that cycle. Patients who were discontinued from therapy prematurely during a cycle were included in the calculation of the particular type of toxicity that the patient had experienced but were excluded from calculations of other toxicities.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Thirty subjects were enrolled in the study from June 2008 through December 2010. There were 1 ineligible (gliomatosis cerebri) and 5 inevaluable for primary response to treatment (3 because of early death or disease progression prior to completing the initial MRI evaluation for response at 4 weeks, 1 withdrawal from protocol by patient/physician choice, and 1 deemed inevaluable by histology after having enrolled prior to the protocol amendment excluding gliomatosis cerebri). The patient characteristics for the 24 evaluable subjects are shown in Table 1, and the reported prior therapies are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The tumor histologies of the evaluable subjects, with central neuropathology confirmation in 14 cases, were GBM (18), AA (3), and high-grade astrocytoma, NOS (3). There were no significant differences in pathology classification between those tumors centrally reviewed and the reporting institution. There was only 1 subject <3 years of age at study entry, and this subject did not receive prior radiation therapy. This patient received an initial diagnosis of GBM at age 6 months of age (confirmed by central review on this study), underwent a gross total resection and was then treated during age 7–12 months with 4 cycles of chemotherapy (temozolomide and lomustine according to the COG ACNS0423 protocol, not in study), and subsequently experienced relapse at 12 months of age and entered the ACNS0621 study at 13 months of age. The remaining patients had all received standard radiation therapy and chemotherapy as part of their initial treatment (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Evaluable patients (n = 24) |

|---|---|

| Age, months (median/range) | 14.2 (1.13–20.3) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 12 (50.0%) |

| Male | 12 (50.0%) |

| Histology reported by site | |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | 4 (16.7%) |

| Glioblastoma multiforme | 15 (62.5%) |

| High-grade astrocytoma, NOS | 5 (20.8%) |

| Histology by reviewa | |

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | 3 (12.5%) |

| Glioblastoma multiforme | 18 (62.5%) |

| High-grade astrocytoma, NOS | 3 (12.5%) |

aFinal histology was determined by central neuropathology review if it differed from the site histology; however, site histology continued to be used in cases that did not have central neuropathology review.

Toxicity

The study drug was well tolerated overall, with toxicity typically infrequent and mild. All grade 2 or higher toxicity (any attribution) is shown in Table 2. Grade 3 or 4 toxicity that was deemed at least possibly related to the study drug included grade 3 lymphopenia (1), grade 3 seizure (1), grade 4 apnea (1), and grade 3 fatigue and grade 4 lymphopenia (1). All of the severe toxicities, including apnea, encephalopathy, decreased level of consciousness, dyspnea, and intracranial hemorrhage, occurred in association with seizures and clinical progression.

Table 2.

Summary of grade 2 or higher toxicities (any attribution) reporteda

| Toxicity Type | Cycle 1 (n = 26b) | Cycle 2 (n = 7c) | Cycle 3 (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apnea | 1 (3.7%b) | 1 (25%) | |

| Buttock pain | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Catheter related infection | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Cognitive disturbance | 1 (14.3%) | ||

| Constipation | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Death NOS | 3 (11.1%b) | ||

| Depressed level consciousness | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Dyspnea | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Encephalopathy | 1 (3.7%b) | ||

| Facial nerve disorder | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Fatigue | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Fever | 1 (3.7%b) | ||

| Headache | 4 (15.4%) | ||

| Hydrocephalus | 1 (14.3%) | ||

| Hypophosphatemia | 1 (14.3%) | ||

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 1 (3.8%) | 1 (25%) | |

| Lymphopenia | 1 (3.8%) | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (25%) |

| Muscle weakness | 2 (7.7%) | ||

| Nervous system disorder NOS | 2 (7.7%) | ||

| Neutropenia | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Peripheral neuropathy | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Seizure | 3 (11.1%b) | 1 (12.5%c) | |

| Skin disorder NOS | 1 (14.3%) | ||

| Upper respiratory infection | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Urinary incontinence | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Vomiting | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| WBC decreased | 1 (3.8%) |

aTwo patients with gliomatosis cerebri were excluded. Two went beyond cycle 3; one had Grade 3 fatigue during cycle 4; the other had Grade 2 urticaria for cycle 14 and 21. All of the severe toxicities, including apnea, encephalopathy, decreased level of consciousness, dyspnea and intracranial hemorrhage, occurred in association with seizures and clinical progression.

bOne patient remained on cycle 1 for 1 week and is excluded from the denominator except for the toxicity reported (death not associated with CTC, n = 27). One patient remained on cycle 1 for 10 days and is also excluded from the denominator except for the toxicities reported (fever, apnea, encephalopathy, seizure, n = 27).

cOne patient did not finish cycle 2 and is excluded from the denominator except for the toxicity reported (seizure, n = 8). One patient stayed on cycle 2 for 10 days without any reportable toxicity and is also excluded from the denominator.

Response

Among the 24 evaluable subjects, only one response was observed (during stage 1). The responder in stage 1 was SD after cycle 1 and cycle 4 without receiving any corticosteroids. This patient received a total of 21 cycles and was last reported as SD after cycle 19. The SD response was observed in the patient <3 years of age with GBM histology confirmed by central review. The 7 nonresponders in stage 1 consisted of 5 PD after cycle 1 and 2 PD after cycle 2 (SD after cycle 1). The 16 nonresponders in stage 2 consisted of 12 PD after cycle 1, 1 PD after cycle 2 (SD after cycle 1), 2 PD after cycle 3 (SD after cycle 1), and 1 PD after cycle 4 (SD after cycle 1–3). Of the 5 inevaluable subjects, there were 3 cases of early clinical progression or death before the initial MRI assessment at 4 weeks could be obtained. Two of the 3 events occurred within 1 week after start of treatment (ie, 2 doses of study drug). The third event was death during the fourth week of treatment.

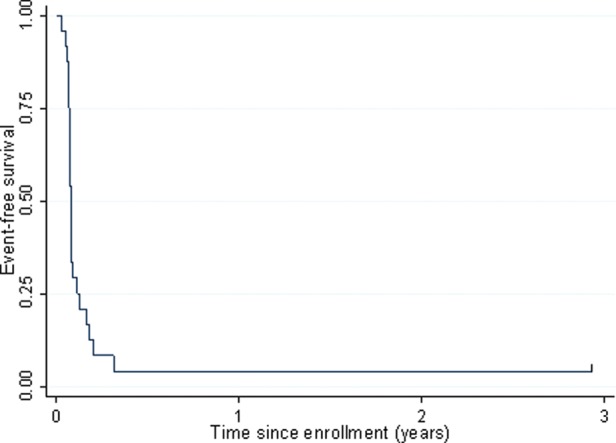

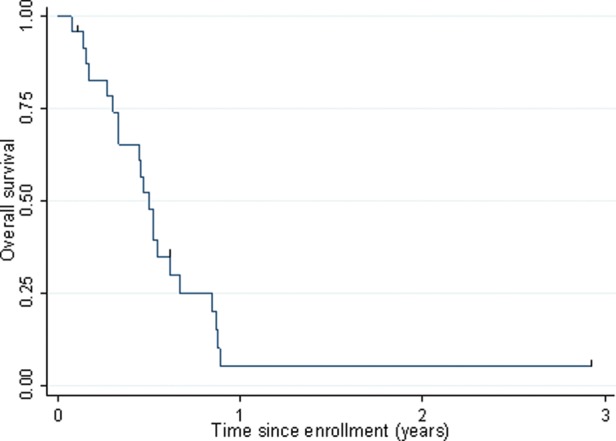

Of the 24 evaluable patients, 23 had a median time to progression of 28 days (range, 11–114 days). No second malignancy was reported. EFS is shown in Fig. 1. The only censored patient had a follow-up of 1068 days. Of the 24 patients evaluable for primary response end point, 21 died, with a medium time from enrollment to death of 172 days (range, 28–325 days). The 3 censored patients had follow-up of 37, 223, and 1068 days, respectively. OS is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

EFS among patients with pHGG enrolled in ACNS0621.

Fig. 2.

OS among patients with pHGG enrolled in ACNS0621.

Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacogenetics

Plasma samples were collected from 18 consenting patients for pharmacokinetic analysis. In 3 patients, only a limited number of samples were collected (missing 1 or 2 samples because of logistical reasons). A summary of cilengitide pharmacokinetic parameters is presented in Supplemental Table S2. The median (range) cilengitide clearance (Clt) and Vc was 3.84 L/h/m2 (2.47–4.75 L/h/m2) and 6.20 L/m2 (3.34–10.72 L/m2), respectively. The median (range) cilengitide AUC0-∞ was 471 µg/mL*h (313–731 µg/mL*h). A representative cilengitide concentration-time is shown in Supplemental Fig. S1. In 20 consenting patients, genotyping studies were performed for 2 polymorphisms in ABCB1 and ABCG2 that encode for the major efflux-transporter proteins P-glycoprotein and BCRP, respectively, which are expressed in the blood-brain barrier and regulate drug distribution to the brain. The following distributions were observed: ABCG2 Exon 2 G/G (n = 16), G/A (n = 1), A/A (n = 2); ABCG2 Exon 5 G/G (n = 16), G/T (n = 3), T/T (n = 0); ABCB1 Exon 26 C/C (n = 7), C/T (n = 8), T/T (n = 5). Genotypes for ABCG2 Exon 5 and ABCB1 Exon 26 fulfilled the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, but the ABCG2 Exon 2 distribution did not. The pharmacogenetic studies failed to yield any statistically significant associations (data not shown) between genetic variants of ABCB1 and ABCG2 and cilengitide systemic clearance.

Discussion

Cilengitide was well tolerated with minimal toxicity; however, it did not demonstrate efficacy in the treatment of refractory pHGG as a single agent. There was one responder with sustained SD for 20 months who had ongoing SD at the time of this report. This patient was an infant with GBM who initially progressed after gross total resection, followed by 4 cycles of monthly temozolomide and CCNU prior to enrollment on this study. The response rate for this study was less than expected on the basis of the prior pediatric and adult experience for refractory HGG treated with cilengitide. In the previous PBTC-012 phase I study of 31 children with refractory CNS tumors, there were 1 CR (GBM) and 6 SD, which included a patient with GBM.15 In the NABTC 03-02 study of adult recurrent GBM, 3 doses of cilengitide (500 or 2000 mg/dose) were given prior to tumor resection, followed by twice weekly cilengitide (2000 mg/dose) for up to 2 years.12 In 26 evaluable patients, cilengitide was detected in all resected tumor specimens, with higher levels observed in the group receiving the 2000 mg dose; however, efficacy was modest, with a reported 6-month PFS of 12%. A similar 6-month PFS of 15% was reported in another phase II study in adult recurrent GBM, in which 81 patients were randomized to receive 500 or 2000 mg/dose twice weekly cilengitide.13 In comparison, a multicenter phase I/II study of twice weekly cilengitide (500 mg) in combination with temozolomide and concomitant radiation followed by maintenance therapy with cilengitide and temozolomide in 52 adult patients with newly diagnosed HGG demonstrated a 12-month PFS of 33%.18 The PFS and OS in the group of patients with tumors having MGMT promoter methylation was significantly longer, compared with those without MGMT methylation and with historical controls. It was suggested that the efficacy observed could be attributable to increased temozolomide delivery to the tumor mediated by cilengitide's effect on normalization of the tumor vasculature. In keeping with this hypothesis, cilengitide demonstrated increased endothelial permeability through disruption of VE-cadherin localization19 without directly enhancing glioma sensitivity to temozolomide in vitro.20 Alternatively, unknown mechanisms of synergism between tumor MGMT promoter methylation, radiation, and cilengitide may exist. Several preclinical studies have demonstrated synergistic anti-glioma activity with the combination of cilengitide and radiation,21,22 and most recently, cilengitide in combination with radiation and temozolomide improved survival among adults with newly diagnosed GBM, regardless of tumor MGMT methylation status.23

The current study supports the pharmacokinetic findings of prior cilengitide trials. Specifically, the median cilengitide systemic clearance in our pediatric population (3.8 L/h/m2) was similar to values in the earlier phase I pediatric trial (4.7 L/h/m2; range, 2.3–9.3 L/h/m2) and in the phase I adult glioma study in patients treated at the same 1800 mg/m2 dose (3.3 L/h/m2).14 AUC values reported here are also similar to the published adult AUC values at the 1800 mg/m2 dose (578 µg/mL*h; range, 426–749 µg/mL*h). Previous preclinical studies have demonstrated αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrin inhibition and in vitro antiangiogenic activity with cilengitide concentrations in the nanomolar to low micromolar range.10,24 Children treated at the 1800 mg/m2 dose in this study exhibited concentrations well above this threshold with typical plasma concentrations 1 h after the end of infusion exceeding 168 µM. Moreover, the range of cilengitide systemic exposure achieved here in children, measured as the AUC0-∞ (313–731 µg/mL*h), exceed values associated with tumor growth suppression in animal models.21

In summary, cilengitide is well tolerated in pHGG but, as seen in other clinical studies, has low to modest anti-tumor activity as a single agent.11–16 However, cilengitide in combination with radiation and chemotherapy, especially temozolomide, has repeatedly shown synergistic activity.18,23,25 Because of the promising results recently demonstrated in adult patients with newly diagnosed GBM treated with cilengitide, temozolomide, and radiation, combination studies of chemoradiotherapy and cilengitide in newly diagnosed pHGG are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Funding

NIH grant no. U10 CA98543-06.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Pollack IF, Hamilton RL, Sobol RW, et al. O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase expression strongly correlates with outcome in childhood malignant gliomas: results from the CCG-945 Cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3431–3437. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen KJ, Pollack IF, Zhou T, et al. Temozolomide in the treatment of high-grade gliomas in children: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:317–323. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reardon DA, Perry JR, Brandes AA, Jalali R, Wick W. Advances in malignant glioma drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2011;6:739–753. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2011.584530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDonald TJ, Aguilera D, Kramm CM. Treatment of high-grade glioma in children and adolescents. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:1049–1058. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Tumor angiogenesis: molecular pathways and therapeutic targets. Nat Med. 2011;17:1359–1370. doi: 10.1038/nm.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabatabai G, Tonn JC, Stupp R, Weller M. The role of integrins in glioma biology and anti-glioma therapies. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:2402–2410. doi: 10.2174/138161211797249189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabatabai G, Weller M, Nabors B, et al. Targeting integrins in malignant glioma. Target Oncol. 2010;5:175–181. doi: 10.1007/s11523-010-0156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reardon DA, Nabors LB, Stupp R, Mikkelsen T. Cilengitide: an integrin-targeting arginine-glycine-aspartic acid peptide with promising activity for glioblastoma multiforme. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:1225–1235. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.8.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDonald TJ, Taga T, Shimada H, et al. Preferential susceptibility of brain tumors to the antiangiogenic effects of an alpha(v) integrin antagonist. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:151–157. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200101000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamada S, Bu XY, Khankaldyyan V, Gonzales-Gomez I, McComb JG, Laug WE. Effect of the angiogenesis inhibitor Cilengitide (EMD 121974) on glioblastoma growth in nude mice. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:1304–1312. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000245622.70344.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reardon DA, Cheresh D. Cilengitide: a prototypic integrin inhibitor for the treatment of glioblastoma and other malignancies. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:1159–1165. doi: 10.1177/1947601912450586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert MR, Kuhn J, Lamborn KR, et al. Cilengitide in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: the results of NABTC 03–02, a phase II trial with measures of treatment delivery. J Neurooncol. 2012;106:147–153. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0650-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reardon DA, Fink KL, Mikkelsen T, et al. Randomized phase II study of cilengitide, an integrin-targeting arginine-glycine-aspartic acid peptide, in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5610–5617. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.7510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nabors LB, Mikkelsen T, Rosenfeld SS, et al. Phase I and correlative biology study of cilengitide in patients with recurrent malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1651–1657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacDonald TJ, Stewart CF, Kocak M, et al. Phase I clinical trial of cilengitide in children with refractory brain tumors: Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium Study PBTC-012. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:919–924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eskens FA, Dumez H, Hoekstra R, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of continuous twice weekly intravenous administration of Cilengitide (EMD 121974), a novel inhibitor of the integrins alphavbeta3 and alphavbeta5 in patients with advanced solid tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:917–926. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'argenio DZ, Schumitzky A, Wang X. ADAPT 5 User's Guide: Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Systems Analysis Software. Los Angeles: Biomedical Simulations Resource; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Neyns B, et al. Phase I/IIa study of cilengitide and temozolomide with concomitant radiotherapy followed by cilengitide and temozolomide maintenance therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2712–2718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alghisi GC, Ponsonnet L, Rüegg C. The integrin antagonist cilengitide activates alphaVbeta3, disrupts VE-cadherin localization at cell junctions and enhances permeability in endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maurer GD, Tritschler I, Adams B, et al. Cilengitide modulates attachment and viability of human glioma cells, but not sensitivity to irradiation or temozolomide in vitro. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11:747–756. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2009-012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikkelsen T, Brodie C, Finniss S, et al. Radiation sensitization of glioblastoma by cilengitide has unanticipated schedule-dependency. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2719–2727. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lomonaco SL, Finniss S, Xiang C, et al. Cilengitide induces autophagy-mediated cell death in glioma cells. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:857–865. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nabors LB, Mikkelsen T, Hegi ME, et al. A safety run-in and randomized phase 2 study of cilengitide combined with chemoradiation for newly diagnosed glioblastoma (NABTT 0306) Cancer. 2012;118:5601–5607. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nisato RE, Tille JC, Jonczyk A, et al. Alphav beta 3 and alphav beta 5 integrin antagonists inhibit angiogenesis in vitro. Angiogenesis. 2003;6:105–119. doi: 10.1023/B:AGEN.0000011801.98187.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beal K, Abrey LE, Gutin PH. Antiangiogenic agents in the treatment of recurrent or newly diagnosed glioblastoma: analysis of single-agent and combined modality approaches. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.