Abstract

Background

ATPase-family, AAA domain containing 3A (ATAD3A) is located on human chromosome 1p36.33, and high endogenous expression may associate with radio- and chemosensitivity. This study was conducted to investigate the significance of ATAD3A in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM).

Methods

Clinical significance of ATAD3A expression was assessed by immunohistochemistry in 67 GBM specimens, and prognostic value was assessed in 32 GBM patients statistically. To investigate in vitro phenotypic effects of ATAD3A, cell viability was measured using a clonogenic survival assay under either knockdown or ectopic expression of ATAD3A in GBM cell lines. The effects of ATAD3A knockdown on targeted DNA repair-associated proteins in T98G cells were evaluated using immunofluorescence and Western blotting.

Results

Clinically, high expression of ATAD3A was independent of O6-DNA methylguanine-methyltransferase methylation status and correlated with worse prognosis. In vitro, high ATAD3A-expressing T98G cells were more resistant to radiation-induced cell death compared with control and low endogenous ATAD3A U87MG cells. After silencing ATAD3A, T98G cells became more sensitive to radiation. On the other hand, enforced ATAD3A expression in U87MG cells exhibited increased radioresistance. ATAD3A may coordinate with aldo-keto reductase genes and participate in bioactivation or detoxication of temozolomide. Surprisingly, deficient DNA repair after irradiation was observed in T98G/ATAD3A knockdown as a result of decreased nuclear ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase and histones H2AX and H3, which was also evidenced by the sustained elevation of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase prior to and after radiation treatment.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that high expression of ATAD3A is an independent biomarker for radioresistance in GBM. ATAD3A could be a potential target for therapy.

Keywords: ATAD3A, autophagy, DNA repair, glioblastoma multiforme, radiation

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is one of the most aggressive brain tumors, with dismal prognosis. More than 70% of GBM patients die within 2 years after diagnosis, even under intensive multimodality chemoradiation with an oral alkylating agent, temozolomide (TMZ).1 Identifying and understanding the biology behind novel chemo- and radioresistant markers in GBM would shed light on improving the current therapeutic approaches. Clinically, the methylation status of the methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) gene promoter is a strong indicator of survival benefits of radiotherapy and TMZ.2 Besides, mutation at codon 132 of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1, which was strongly associated with codeletion of 1p or 19q, was prognostic as well for secondary GBM.3,4 However, the incidence of isolated 1p or 19q deletions among primary GBM has been low, at 6.2% and 5.3%, respectively.5

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase (ATM) responds to DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs) immediately following radiation exposure. In gliomas, ATM plays a critical role in radiation resistance,6 and the expression level of ATM dramatically alters radiosensitivity in GBM.7,8 Since ATM became an attractive target for tumor radiosensitization, several inhibitors of ATM activity have been developed, aimed to improve radiotherapy. However, ATM inhibitors were reported to be effective in eliminating only cancer cells that express functional ATM protein with already compromised DNA repairs.9 Recently, ATM was found to be tightly associated with mitochondrial homeostasis, and it has been suggested that ataxia-telangiectasia could be considered as a part of mitochondrial disease.10

Mitochondria play essential roles in cancer progression, in particular in metabolically remodeled phenotypes, which predominantly use aerobic glycolysis as an energy source (Warburg effect).11 Accumulated evidence indicates that some nucleus-encoded mitochondrial proteins are involved in tumorigenesis.12 An altered mitochondrial genome has been frequently found in GBM and shown to adapt to bioenergetic stress.13,14 Furthermore, mitochondrial dysfunction was reported to be associated with increasing damage to reactive oxygen species and the onset of several neurodegenerative diseases and neoplasms.15 Therefore, mitochondrial proteins indeed might be novel therapeutic targets to implement the existing treatments of GBM.16

The ATPase family, AAA domain containing 3A (ATAD3A; 66 kDa) is an essential mitochondrial enzyme involved in maintaining mitochondrial functions and communication between endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria.17–19 ATAD3A was first identified as a tumor-specific antigen20,21 and was later shown to have roles in lung adenocarcinoma,19 uterine cervical cancer,22 and prostate cancer.23 Its clinical significance was further supported by in vitro data, in which cancer cells with ATAD3A overexpression were more resistant to anticancer drugs.21 Interestingly, the ATAD3A gene is located on human chromosome 1p36.33 and has been shown in human glioma cell lines to be correlated with cell growth and resistance to genotoxic drugs.24 Although deletion/alteration in the distal short arm of chromosome 1 (1p) has been associated with chemo- and radiosensitivity in oligodendrogliomas and other brain tumors, no specific tumor-related gene to date has been identified as conferring this to a treatment-resistant phenotype.25,26 In this report, we demonstrate that ATAD3A expression correlates with treatment response in a primary GBM chemoradiation cohort, implicating ATAD3A as a possible prognostic marker and therapeutic target in GBM. We also investigated the ATAD3A-associated chemo- and radioresistant mechanisms in GBM.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Specimens and Immunohistochemical Detection of ATAD3A Expression

The protocol of the study, including tissue specimen collection, pathology evaluation, and survival assessment, was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital. Tissue microarrays of 35 American GBM samples (GL806, US Biomax) were used to compare ATAD3A expression between American and our GBM patients. Immunohistological staining was performed on paraffin sections using a labeled streptavidin–biotin method (Dako).18,19,22,23 The chromogenic reaction was visualized by peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin and aminoethyl carbazole (Sigma). Samples were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. Slides were evaluated by 2 independent pathologists without knowledge of patient's’ clinicopathological background. An immune-reaction scoring system was adapted for this study.27 Briefly, a specimen was considered to have strong signals when >50% of cancer cells were positively stained; intermediate signals if 25%–50% of cells were positively stained; weak signals if <25% or >10% of cells were positively stained; and negative signals if <10% of cancer cells were positively stained. The samples with strong and intermediate signals were classified as ATAD3A+; those with weak or negative signals were classified as ATAD3A–.

MGMT Status by Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 32 paraffin wax embedded samples of GBM patients using a standard TRIzol protocol. RNA quantity was examined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total RNA was reverse transcribed using cDNA by random hexamer primers and the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) according to the manufacturers' protocol. Real-time PCR was carried out in triplicates in 48-well plates using the StepOne RT-PCR machine (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies). Forward primer was GCGTTTCGACGTTCGTAGGT; reverse primer was CACTCTTCCGAAAACGAAACG; and the probe was 6FAM-AAACGATACGCACCGCGA-MGB in the assay.

Cell Culture and Alteration of ATAD3A Expression Using Lentivirus-carrying Short Hairpin RNA and Ectopic Plasmid

Human GBM cell lines U87MG (malignant glioma) and T98G were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 4 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cells were grown to 80% confluence on the day of infection. Lentivirus-carrying ATAD3A short hairpin (sh)RNA was prepared using a 3-plasmid transfection method.28 The product lentivirus was used to infect T98G cells in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene, and cells with ATAD3A gene knockdown (ATAD3Akd) were selected using 1 μg/mL puromycin. For ectopic expression, pCMV-SPORT6-ATAD3A (www.Invitrogen.com) was delivered into U87MG cells by the ECM 399 electroporation system (BTX Harvard Apparatus).

Immunoblotting Analysis

The procedure for immunoblotting has been described previously.18,19,22,23 Briefly, 30 μg of total cell lysate was separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel with 4.5% stacking gel. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was then probed with specific antibodies. The protein was visualized by exposing the membrane to X-Omat film (Eastman Kodak) with enhanced chemiluminescent reagent (Merck). The respective primary antibodies were mouse anti-ATAD3A, mouse anti–dihydrodiol dehydrogenase (DDH), mouse anti–Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1 (NBS1), mouse anti–checkpoint kinase 2, mouse anti–epidermal growth factor receptor, mouse anti–human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), mouse anti–β-actin, rabbit anti–poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), rabbit anti-histone H3, rabbit anti-p53, rabbit anti–light chain 3 (LC3), rabbit anti-ATM, rabbit anti–phosphorylated (phospho-) ATM (Ser1981), rabbit anti-histone H2AX, and rabbit anti–phospho-γ-H2AX (Ser193). Rabbit antisera were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. The digital images on X-Omat film were processed in Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (http://www.adobe.com/). The blots were stripped using Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) before incubation with other antibodies. The results were analyzed and quantified by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Colony-forming Assay and γ-H2AX Assay

T98G/empty vector (EV), T98G/ATAD3Akd, U87MG/EV, and U87MG with enforced ATAD3A expression (U87MG/ATAD3Aee) cells were separately treated with 3, 6, or 12 Gy of radiation (Varian Oncology Systems 21EX linear accelerator). Following radiation, cells were trypsinized and reseeded at 100, 500, 2000, and 5000 cells/well culture plates, respectively. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 10 days, visible colonies that contained >50 cells were counted, and plating efficiency was determined. A semilog graph was plotted of the cell survival fractions (ratio of colonies formed by irradiated cells to colonies formed by control cells) against radiation dosage.

The γ-H2AX foci were detected by antibodies specific to γ-H2AX and observed by a laser scanning confocal microscope 1 h postradiation (6 Gy). The method for immunofluorescence confocal microscopy has been described previously.18,19,22,23 Briefly, the cells on slides were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 prior to staining with rabbit anti–γ-H2AX (1 : 100). After washing off the primary antibodies, the slides were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Invitrogen). The nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and the slides were examined under a laser confocal microscope (Olympus FV-1000). Images of the cells were analyzed by FV10-ASW 3.0 software (Olympus).

Electron Microscopy

Electron microscopy was carried out using a routine protocol. Briefly, cells were fixed in situ on culture dishes with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma) in 100 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2) at 4°C overnight. Cells were washed with PBS before postfixation with 1% osmium tetroxide in PBS for 1 h. After washing with distilled water, the cells were suspended in 2% molten agarose, and the agarose blocks were trimmed and dehydrated in a serial dilution of ethanol for 15 min each. The blocks were further dehydrated 3 times using 100% ethanol for 15 min each and infiltrated with 100% ethanol/LR white (1 : 1) mixture overnight. The blocks were changed to LR white (Agar Scientific) for continuous infiltration at 4°C for 24 h before being transferred to a capsule filled with LR white. LR white was polymerized and solidified at 60°C for 48 h. The resin blocks were trimmed and cut with ultramicrotome (Leica Ultracut R). Thin sections were transferred to 200 mesh copper grids and stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 15 min and 2.66% lead citrate (pH 12.0) for 15 min prior to observation with an electron microscope (JEM1400, JEOL) at 100–120 kV.

Gel Electrophoretic Analysis of DNA Double-Stranded Breaks

The cells were collected by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 5 min and washed once with cold isotonic buffer (20 mM Hepes [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine ethanesulfonic acid], pH 7.5; 5 mM KCl; 0.5 mM MgCl2; 0.5 mM dithiothreitol; 0.2 M sucrose). The cells were resuspended in cold hypotonic buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5; 5 mM KCl; 0.5 mM MgCl2; 0.5 mM dithiothreitol) and allowed to swell for 10 min on ice. The plasma membrane was broken down by 10 strokes of a tight-fitting Dounce homogenizer. The resulting mixture was centrifuged at 2000 × g for 5 min to remove membrane debris. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, and 10% sucrose.18 Following disruption of the nuclear membrane by 1% NP-40 (nonyl phenoxypolyethoxylethanol) and repeated washing, the ends of DNA fragments were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–deoxythymidine triphosphate and terminal transferase. The reaction was stopped by addition of 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The reaction mixture was heated at 80°C for 5 min, and the reaction products were resolved in 2% agarose gel with 0.1% SDS. The DNA was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed by alkaline phosphatase–conjugated rabbit anti-FITC antibodies. The DNA fragments were visualized by exposing the membrane to X-Omat film with enhanced chemiluminescent reagent.

Statistical Analysis

Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were the times from the date of diagnosis until the date of progression and death, respectively. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier estimator, and the statistical difference in survival between the different groups was compared by a log-rank test. A 2-tailed t-test was used to compare clonogenic survival and clinical parameters. Differences in patients' performance status, tumor location, and surgical resection status were assessed by chi-square or Fisher's exact test. Analyses of the data were performed using SPSS 10.3 software. Statistical tests were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Identification and Validation of Endogenous ATAD3A Expression in GBM

In our previous work, 66-kDa ATAD3A and 70-kDa ATAD3A were identified as serine/threonine phosphorylated isoforms by immunoprecipitation and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (Fig. 1A).19 Of note, only the 70-kDa ATAD3A, not the 66-kDa isoform, could be detected in normal mouse brain (Fig. 1B). To determine the protein level of endogenous ATAD3A in brain tumors, a mouse glioma cell line (H4), 2 human GBM cell lines (U87MG and T98G), and 3 human GBM stem cell lines were investigated by immunoblotting. We observed high endogenous ATAD3A expression in H4 and T98G, as well as CD133+ human GBM stem cells. Interestingly, its expression correlated with HER2 (ErbB-2, neuro/GBM derived oncogene homolog [Neu]; Fig. 1C). Indeed, both the 66- and 70-kDa isoforms were detected in H4, U87MG, and T98G cell lines; we found that only the single 66-kDa protein band was presented in human GBM stem cells and human GBM specimens (Fig. 1D). These results corresponded well with our previous finding in lung cancer that only the 66-kDa isoform could be found in human pathologic specimens.19

Fig. 1.

Identification and validation of endogenous ATAD3A expression in GBM cell lines. (A) Illustration of 66-/70-kDa ATAD3A. (B) Only 70-kDa ATAD3A could be detected in normal mouse brain tissue. (C) The endogenous ATAD3A expression was high in mouse H4 and human T98G cells and in human GBM stem cells, especially in CD133+ stem cells, and corresponded well with HER2 expression. (D) Only 66-kDa ATAD3A could be detected in human GBM specimens. Abbreviation: GSC, glioma stem cell.

Expression of ATAD3A in GBM and Its Prognostic Value

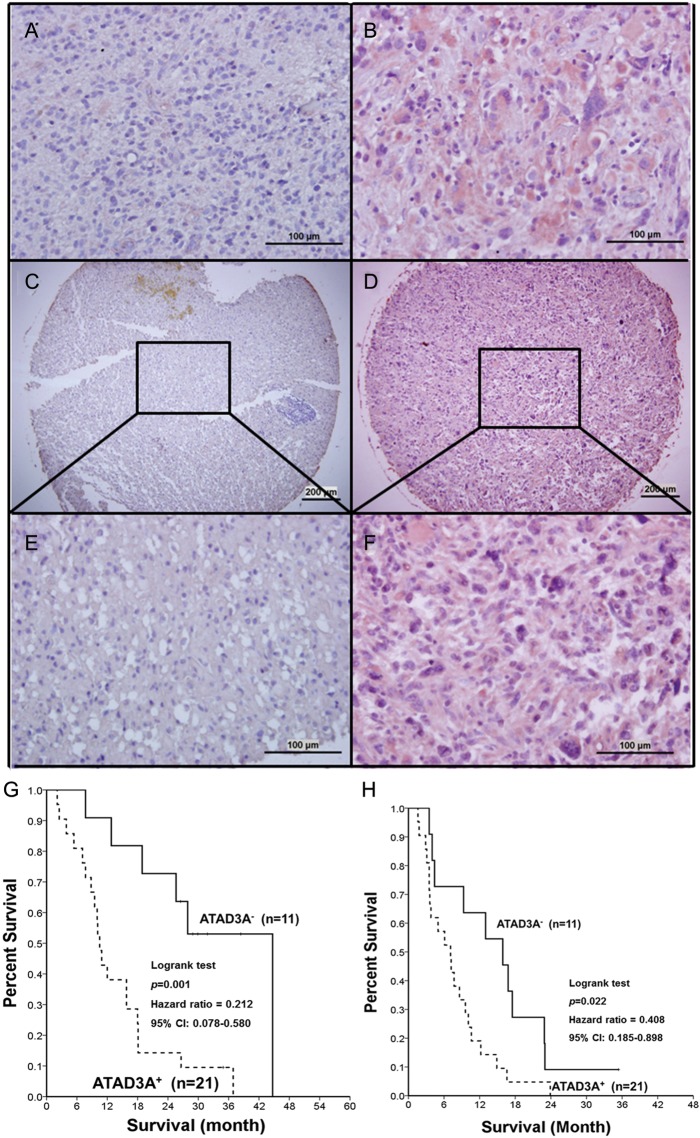

From August 2008 to October 2010, 32 GBM patients who received standard chemoradiation with daily TMZ (75 mg/m2) and adjuvant monthly TMZ (150–200 mg/m2) were retrospectively reviewed in this study. Demographics and treatment parameters of these patients are listed in Table 1. Using immunohistochemical staining, the expression level of ATAD3A was classified as ATAD3A+ in 21 of 32 (65.6%) GBM patients (Fig. 2A and B) and in 25 of 35 (71.4%) American GBM samples (P = .609; Figs 1F–2C). No significant correlation was found between MGMT and ATAD3A in tumor specimens.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with different ATAD3A expression levels

| Characteristic | ATAD3A− (n = 11) | ATAD3A+ (n = 21) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | .205a | ||

| M | 5 | 15 | |

| F | 6 | 6 | |

| Age, y | 55.6 ± 12.0 | 56.2 ± 18.3 | .923b |

| KPS | .391a | ||

| 60 | 1 | 3 | |

| 70–80 | 10 | 16 | |

| 90 | 0 | 2 | |

| RTOG RPA | .717a | ||

| III | 0 | 2 | |

| IV | 3 | 4 | |

| V–VI | 8 | 15 | |

| Surgical resection status | .177a | ||

| Gross total | 9 | 20 | |

| Partial | 2 | 0 | |

| Biopsy only | 0 | 1 | |

| Tumor location | .866 | ||

| Right | 7 | 13 | |

| Left | 4 | 8 | |

| Frontal | 4 | 4 | |

| Parietal | 1 | 3 | |

| Occipital | 2 | 4 | |

| Temporal | 3 | 8 | |

| Others | 1 | 2 | |

| MGMT status | .681a | ||

| Methylated | 4 | 5 | |

| Unmethylated | 7 | 16 | |

| Radiotherapy dose | 5912.7 ± 289.5 | 5840.0 ± 408.9 | .605b |

| TMZ cycle | 7.29 ± 2.6 | 6.63 ± 5.7 | .773b |

| MRI assessment | |||

| Gross tumor volume | 56.6 ± 34.9 | 53.9 ± 28.9 | .846b |

| Edematous volume | 141.8 ± 73.8 | 147.8 ± 67.5 | .850b |

Abbreviation: RTOG RPA, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Recursive Partitioning Analysis.

aAnalysis by Fisher's exact test (2-tailed, trend).

bAnalysis by t-test (2-tailed).

Fig. 2.

Representative examples of ATAD3A expression level in GBM specimens by immunohistochemical staining (as crimson precipitates in cytoplasm). The slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. Illustration of (A) ATAD3A− and (B) ATAD3A+ in our patients (original magnification × 400). Illustration of (C) ATAD3A− and (D) ATAD3A+ in American GBM specimens (original magnification × 50). (E) An enlarged image of (C). (F) An enlarged image of (D) (original magnification × 400). (G) Comparison of Kaplan–Meier product limit estimates of survival analysis in 32 GBM patients. Patients with ATAD3A+ phenotype had significantly poorer OS (P = .01) and (H) PFS (P = .013).

At the time of data analysis (followed at least 24 months), 5 of 11 (45.5%) ATAD3A+ patients were alive, and 1 was progression free. The ATAD3A− patients had significantly better OS and PFS (P = .001 and P = .022, respectively; Fig. 2G and H). Multivariate analysis of age, KPS, MGMT status, and ATAD3A− demonstrated that ATAD3A− was an independent prognostic factor (P = .005, hazard ratio = 0.161, 95% confidence interval = 0.045–0.57). It is worthwhile to note that the ATAD3A− patients with methylated MGMT had the best prognosis (Fig. 2I).

Endogenous ATAD3A Expression Correlated With Radiosensitivity and TMZ Resistance

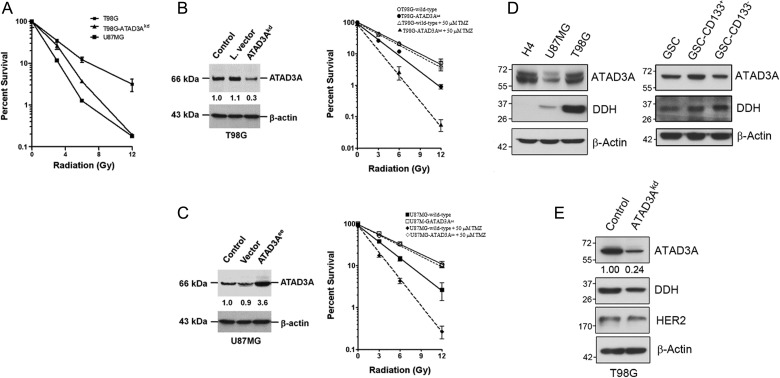

These data raised a possibility that ATAD3A+ is a prognostic phenotype as a result of radiation or TMZ resistance. On the basis of this hypothesis, we used the colony-forming assay to determine the viability of GBM cells after irradiation. First, high ATAD3A-expressing T98G cells exhibited higher resistance to radiation compared with low ATAD3A-expressing U87MG cells (P = .001; Fig. 3A). To further investigate whether ATAD3A could modulate radiosensitivity in GBM, we used T98G/EV and T98G cells stably transfected with lentivirus-carrying shRNA (T98G/ATAD3Akd) and U87MG/EV and U87MG cells stably transfected with ATAD3A expression vector (U87MG/ATAD3Aee). As shown by immunoblotting, U87MG/ATAD3Aee and T98G/EV cells, which exhibited constitutive expression of ATAD3A, had increased levels of ATAD3A protein compared with U87MG/EV and T98G/ATAD3Akd cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Endogenous ATAD3A expression correlates with radiosensitivity in GBM cells. (A) Cell viability of wild-type T98G, wild-type U87MG, and T98G/ATAD3Akd cells by colony-forming assay after different radiation dose treatments. The wild-type T98G, U87MG, and T98G/ATAD3Akd cells were exposed to irradiation (0, 3, 6, or 12 Gy) and incubated for 10 days until colonies appeared. Viability was assessed following staining of colonies by crystal violet. Cell viability was evidently reduced in T98G-ATAD3Akd cells, suggesting that ATAD3A expression correlated with radiosensitivity. (B) Validation of silencing of ATAD3A expression (ATAD3Akd) by immunoblot. Reduced cell viability of ATAD3Akd cells after irradiation with and without TMZ (as measured by colony-formation assay). ○, T98G/EV cells; •, T98G/ATAD3Akd cells. Adding 50 μM TMZ radiosensitized T98G/ATAD3Akd (▴) but not T98G/EV (▵) cells. (C) Validation of enforced ATAD3A expression (ATAD3Aee) by immunoblotting. Radioresistance by ATAD3Aee was seen in U87MG cells after irradiation with and without TMZ. ▪, U87MG/EV cells; □, U87MG/ATAD3Aee cells. TMZ radiosensitized U87MG/EV cells (♦) but did not affect cell viability of U87MG/ATAD3Aee cells (¯). (D) The expression between ATAD3A and DDH is highly correlated, as shown by immunoblotting. GSC, glioma stem cell. (E) Knockdown of ATAD3A reduced DDH expression in T98G cells.

As expected, a drastic loss of colony-forming ability occurred after irradiation when T98G cells were treated with ATAD3Akd (P = .009; Fig. 3D). The combination of TMZ and radiation significantly decreased the survival fraction of T98G/ATAD3Akd cells, but not T98G/EV cells (P = .002). On the other hand, enforced expression of ATAD3A significantly increased radiation resistance (P = .005; Fig. 3E). Addition of TMZ could radiosensitize only U87MG/EV (P< .001) but not U87MG/ATAD3Aee cells, implying that ATAD3A may have a role in TMZ efficacy (Fig. 3C). We therefore used an oligonucleotide microarray to identify regulating genes that could be involved in TMZ and radiation resistance of T98G/ATAD3Akd cells. As shown in Table 2, several DNA repair-related genes, including H2AFX, Rad9B, Hus1B, MSH4, and LIG4, were affected by silence of ATAD3A but not MGMT. Most importantly, we found aldo-keto reductase (AKR) family genes that took part in resistance to cisplatin and TMZ. Markedly suppressed by ATAD3Akd were AKR1B10, AKR1B15, AKR1C1, AKR1C3, and AKR1C4. Further immunoblotting corroborated that DDH was coexpressed with ATAD3A in GBM cell lines (Fig. 3D), and the expression was reduced as well in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells (Fig. 3E).

Table 2.

Downregulation of AKR family and DNA repair-associated genes in ATAD3Akd T98G cells as determined by oligonucleotide microarray

| Gene Name | Roles in DNA Repair Process | Relative Changea (n)b |

|---|---|---|

| ATAD3A | 0.370 (1) | |

| DNA damage sensors | ||

| MGMT | 1.094 (2) | |

| H2AFX | DNA damage response transducer | 0.769 (2) |

| Rad9B | 9-1-1 complex | 0.257 (1) |

| Hus1B | 9-1-1 complex | 0.572 (1) |

| DNA damage repair | ||

| MSH4 | DNA mismatch repair | 0.569 (2) |

| LIG4 | DNA DSB repair | 0.446 (2) |

| Drug resistance-related gene | ||

| AKR1B10 | Genotoxic stress response | 0.282 (3) |

| AKR1B15 | Genotoxic stress response | 0.089 (1) |

| AKR1C1 | Genotoxic stress response | 0.197 (3) |

| AKR1C3 | Genotoxic stress response | 0.119 (3) |

| AKR1C4 | Genotoxic stress response | 0.721 (3) |

| AKR1CL1 | Genotoxic stress response | 0.576 (1) |

aRelative change was calculated by dividing the intensity of gene expression level detected on the oligonucleotide microarray from ATAD3Akd T98G cells with wild-type cells.

bNumber of spots in the oligonucleotide microarray.

Silence of ATAD3A Abated Repair of Radiation-Induced DNA Damage

Based on our results, it was reasonable to hypothesize that modulation of radioresistance by ATAD3A in GBM was related to DNA DSB repairs. Surprisingly, our initial studies revealed that the number of γ-H2AX foci in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells not only was less than wild-type T98 cell lines, but even dropped significantly lower upon 6-Gy radiation (P < .001; Fig. 4A and B). To ensure the status of unrepaired DSBs, gel electrophoresis assay was performed 4 h after radiation treatment and showed that silencing of ATAD3A mitigated DSB repairs in T98G cells, corroborated by the results of γ-H2AX studies (Fig. 4C). Although the immunoblotting of whole cell and nuclear protein extraction showed elevated ATM and NBS1 in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells prior to irradiation, markedly attenuated γ-H2AX, upstream phospho-ATM-S1981, ATM, and NBS1 were found after radiation treatment (Fig. 4 D). Nuclear histones H2AX and H3 were found greatly reduced as well, supporting the status of deficient DSB repairs in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells after irradiation (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Silencing of ATAD3A attenuated DNA repairs before and after irradiation. (A, B) Comparison of the average γ-H2AX foci number (red fluorescence) between wild-type and T98G/ATAD3Akd cells before and after 6-Gy radiation. Prior to 6-Gy radiation treatment, the number of γ-H2AX foci was marginally reduced in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells and was significantly decreased 1 h postirradiation compared with wild-type cells, ***P < .001. (C) Gel electrophoresis assay for DSBs. Compared with control and vector-transfected cells, DNA DSBs were more frequent in ATAD3Akd T98G cells prior to radiation. Four hours postradiation (6 Gy), DSBs remained evident in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells, whereas those in the control and vector-transfected cells were mostly mended. (D) Immunoblotting of whole cell and nuclear protein extraction of wild-type and T98G/ATAD3Akd cells. Attenuated γ-H2AX was evident in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells before and after radiation treatment. Autophosphorylation of ATM on Ser1981 in response to irradiation was diminished in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells, as well as ATM and NBS1 compared with those in the wild-type T98G cells, indicating that DNA repairs might be affected. Chk2, checkpoint kinase 2.

ATAD3A Silence-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction Alters Nuclear ATM

Our previous studies showed that ATAD3A, an ATPase, might interact with mitofusin-2 and dynamin-related protein 1 and act together in communication between the ER and mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM).19 ATM contains a potential signal peptide motif (analyzed by SignalP, http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/; Supplementary material Fig. S1) and an ER membrane retention signal sequence, WKAW, at the C-terminus of the protein (Psort II prediction, http://psort.hgc.jp/form2.html), supporting the view that ATM could be targeting to the ER and mitochondrial membrane network. It was reported as well that a fraction of ATM protein is localized in mitochondria and could be activated by mitochondrial dysfunction.29 Knockdown of ATAD3A could significantly affect the state of mitochondrial integrity, resulting in dysfunction of mitochondria-ER contact sites, and thus alter ATM. Electron micrographs provided the evidence that ATAD3A silencing increased autophagy-like vacuoles with encased mitochondria in T98G cells (Fig. 5A). Immunoblotting of nuclear protein extractions and confocal immunofluorescent micrographs demonstrated that nuclear ATM was decreased in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells after irradiation, leaving a noticeable amount of cytoplasmic ATM, corresponding well with immunoblotting data (Fig. 5B and C). We reasoned that in mitochondrial dysfunction and deficient DNA DSB repair, T98G/ATAD3Akd cells would go on a classic apoptotic pathway. We therefore examined the cytologic effect of ATAD3A on apoptotic pathways following irradiation using sub-G0/G1 analysis. Interestingly, the increase of sub-G1 fractions in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells was minimal up to 72 h posttreatment compared with the wild-type cells (Fig. 5D), indicating that although ATAD3A silencing was associated with deficient DNA DSB repairs, the status might not directly induce apoptosis. This also was supported by immunoblotting data, in which knockdown of ATAD3A did not evidently enhance apoptosis (as determined by an increase of cleaved PARP; Fig. 5D).30 Type II autophagic cell death (as determined by an increase of converted microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B–LC3; Fig. 5E) seems the best possibility. However, increased autophagy did not invariably lead to cell death. In addition, sustained elevation of PARP in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells before and after irradiation not only indicated an activation of an alternative pathway of DSBs as a result of hindering ATM and H2AX-mediated DNA repair, but also raised the possibility of type III necrotic cell death.

Fig. 5.

Type of cell death after irradiation in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells. (A) ATAD3Akd increased autophagy-like vacuoles (black arrows), as shown in transmission electron micrographs. (B) Decreased nuclear ATM and a noticeable amount of cytoplasmic ATM were observed in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells after irradiation by confocal immunofluorescent micrographs. (C) Immunoblotting confirmed attenuated ATM in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells after irradiation. (D) Irradiation did not increase apoptotic cell death as assessed by sub-G1 population in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells. (E) No difference of cleaved PARP but markedly activated PARP-1 before and after irradiation was noted in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells. Instead, conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II was evident after irradiation. LC3-II/LC3-I ratio was normalized with corresponding β-actin level.

Discussion

The clinical outcomes of 32 newly diagnosed GBM cases in our study suggested that ATAD3A overexpression in GBM is independent of MGMT promoter methylation status and could be a prognostic marker in GBM. Subgroup analysis indicated not only that ATAD3A was a significant marker for survival, but that the ATAD3A− GBM patients with methylated MGMT had the best prognoses. In accordance, high endogenous ATAD3A confers a radioresistant phenotype in T98G and U87MG cells in vitro. Silencing of ATAD3A enhanced radiosensitivity of radioresistant T98G cells. Enforced expression of ATAD3A, on the other hand, increased radiation resistance of low ATAD3A-expressing U87MG cells. It is reasonable to suspect that the worst survival of the GBM patients with high ATAD3A expression was due to a treatment-resistant phenotype.

Our preliminary results demonstrated that high endogenous ATAD3A expression could be a prognostic phenotype for TMZ resistance as well. Although the endogenous ATAD3A expression of T98G (unmethylated MGMT) happened to be higher than U87MG (methylated MGMT), MGMT genes were not affected by silencing of ATAD3A in T98G cells. An elegant study by Oliva et al31 showed that TMZ could not only introduce intranuclear DNA damage, but also alter activities of the electron transport chain in mitochondria by increasing oxidative phosphorylation via cytochrome c oxidase and reducing production of reactive oxygen species via oxidoreductase in complex I. A report by Le Calvé et al32 showed that long-term treatment of GBM cells with TMZ in vitro could increase drug resistance by upregulating expressions of AKR and glucose transporter, which ultimately affect oxidative metabolism of mitochondria. Overexpression of AKR enzymes was associated with cisplatin resistance and disease progression.33–35 In our study, TMZ could radiosensitize only low ATAD3A-expressing U87MG/EV and T98G/ATAD3Akd cells but not high ATAD3A-expressing T98G/EV and U87MG/ATAD3Aee cells. Using immunoblotting and microarray, we speculated that ATAD3A coordinated with DDH as well as expressions of AKR genes and participated in bioactivation or detoxication of TMZ.

Silencing of ATAD3A influences not only mitochondrial function, but also defecting radiation-induced DNA DSB repairs via manipulating nuclear ATM and H2AX compartmentalization. It is known that radiation can induce a range of DNA damage, including single-stranded breaks and DSBs that both promote genomic as well as mitochondrial instability; and a drastic increase (2.5-fold) of mitochondrial DNA would result 48 h after irradiation in fibroblasts compared with nonirradiated control.36 In particular, increased ATM has also been reported in mitochondrial fractions of wild-type lymphoblastoid cells after irradiation, and ATM deficiency would result in defects in mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial DNA content upon radiation treatment.29 Furthermore, in the study by Watters et al,37 ATM was recognized by ER-associated peroxisome targeting signal type 1 (PTS1) via the PTS1 receptor (Pex5p) and got imported into peroxisomes via the PTS1 pathway. The relative amount of ATM in the postmitochondrial fraction in peroxisome-disordered fibroblasts is significantly reduced compared with the norm, supporting our results that ATM could be targeted to MAMs by ATAD3A. As shown in our study by immunoblotting and confocal immunofluorescent micrographs, increased cytoplasmic ATM was apparently located in ER-like granular structures following irradiation, distinct from the usual dominant nuclear pattern in wild-type T98G cells. Our results also corresponded well with those in the study by Li et al,38 showing that only nuclear, not cytoplasmic, ATM is related to the DNA damage response. In addition, nuclear H2AX was greatly affected after silencing of ATAD3A in the present study, indicating that ATAD3A involves an undiscovered novel mechanism, thus targeting H2AX as well. In a recent study, Cascone et al39 reported that both linker histone H1 and core histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 bind strongly to isolated mitochondria and permeabilize the outer mitochondrial membrane. Knockdown of ATAD3A also has been shown to significantly reduce mitochondrial integrity, mostly as a result of transport of lipids.40 Altogether our data raised a possibility that ATAD3A silencing may affect MAMs, thus hindering ATM trafficking; but its underlying mechanism remains to be delineated.

ATAD3A can also be involved in a non-apoptotic death pathway in T98G cells. To be specific, even though ATAD3Akd cells displayed an inverse LC3-I/II ratio and increased autophagy-like vacuoles in transmission electron micrographs, activation of PARP before and after irradiation may provide a key hole we can look through. In the study by Meador et al,41 H2AX-deficient cells showed elevated PARP-1 activity in response to DNA damage, supporting our observation in T98G/ATAD3Akd cells. Despite the numerous controversies on the role of autophagy in mammalian cells, it essentially is a self-limited process to maintain bioenergetics for survival.42 The autophagic cells will eventually die of necrosis as long as their internal resources are exhausted. Extensive DNA damage by irradiation is attributed to the fact that PARP activation could lead to the rapid depletion of nuclear and cytoplasmic NAD.43 As a consequence, T98G/ATAD3Akd cells dependent on glycolysis for ATP quickly became ATP depleted following PARP activation and died by necrosis.

In conclusion, our data clearly demonstrated that ATAD3A takes part in both the nuclear translocation of ATM and a non-apoptotic pathway. A recent study42 of mitochondrial dysfunction echoes our findings that ATM is directly associated with mitochondria and is easily detectable in mitochondrial fractions of human fibroblast. Although the size of the patient population was small in our study, our results provide a novel link of ATAD3A to the phenotype of radioresistance in GBM.

Supplementary Material

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Taichung Veterans General Hospital Clinical Research (101DHA0500377); the Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taipei, Taiwan, to the China Medical University Hospital, Cancer Research of Excellence program (DOH101-TD-C-111–005); and the National Science Council (NSC 101-2320-B-005-002).

References

- 1.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreana LR, Christopher EP, Mark R, et al. MGMT promoter methylation is predictive of response to radiotherapy and prognostic in the absence of adjuvant alkylating chemotherapy for glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:116–121. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nobusawa S, Watanabe T, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. IDH1 mutations as molecular signature and predictive factor of secondary glioblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6002–6007. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labussière M, Idbaih A, Wang XW, et al. All the 1p19q codeleted gliomas are mutated on IDH1 or IDH2. Neurology. 2010;74(23):1886–1890. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e1cf3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaneshiro D, Kobayashi T, Chao ST, Suh J, Prayson RA. Chromosome 1p and 19q deletions in glioblastoma multiforme. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2009;17(6):512–516. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181a2c6a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Squatrito M, Brennan CW, Helmy K, Huse JT, Petrini JH, Holland EC. Loss of ATM/Chk2/p53 pathway components accelerates tumor development and contributes to radiation resistance in gliomas. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(6):619–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roy K, Wang L, Makrigiorgos GM, Price BD. Methylation of the ATM promoter in glioma cells alters ionizing radiation sensitivity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344(3):821–826. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tribius S, Pidel A, Casper D. ATM protein expression correlates with radioresistance in primary glioblastoma cells in culture. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(2):511–523. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01489-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi S, Gamper AM, White JS, Bakkenist CJ. Inhibition of ATM kinase activity does not phenocopy ATM protein disruption: implications for the clinical utility of ATM kinase inhibitors. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(20):4052–4057. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.20.13471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valentin-Vega YA, Maclean KH, Tait-Mulder J, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in ataxia-telangiectasia. Blood. 2012;119(6):1490–1500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-373639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modica-Napolitano JS, Kulawiec M, Singh KK. Mitochondria and human cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:121–131. doi: 10.2174/156652407779940495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dmitrenko V, Shostak K, Boyko O, et al. Reduction of the transcription level of the mitochondrial genome in human glioblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2005;218:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirches E, Krause G, Warich-Kirches M, et al. High frequency of mitochondrial DNA mutations in glioblastoma multiforme identified by direct sequence. Int J Cancer. 2001;93(4):534–538. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Moura MB, dos Santos LS, Van HB. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2010;51(5):391–405. doi: 10.1002/em.20575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griguer CE, Oliva CR. Bioenergetics pathways and therapeutic resistance in gliomas: emerging role of mitochondria. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(23):2421–2427. doi: 10.2174/138161211797249251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilquin B, Cannon BR, Hubstenberger A, et al. The calcium-dependent interaction between S100B and the mitochondrial AAA ATPase ATAD3A and the role of this complex in the cytoplasmic processing of ATAD3A. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2724–2736. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01468-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiang SF, Huang CY, Lin TY, Chiou SH, Chow KC. An alternative import pathway of AIF to the mitochondria. Int J Mol Med. 2012;29:365–372. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang HY, Chang CL, Hsu SH, et al. ATPase family AAA domain-containing 3A is a novel anti-apoptotic factor in lung adenocarcinoma cells. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1171–1180. doi: 10.1242/jcs.062034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geuijen CA, Bijl N, Smit RC, et al. A proteomic approach to tumour target identification using phage display, affinity purification and mass. Eur J Cancer 2005. 41:178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gires O, Munz M, Schaffrik M, et al. Profile identification of disease-associated humoral antigens using AMIDA, a novel proteomics-based technology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:1198–1207. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4045-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen TC, Hung YC, Lin TY, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and expression of ATPase family AAA domain containing 3A, a novel anti-autophagy factor, in uterine cervical cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2011;28:689–696. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang KH, Chow KC, Chang HW, Lin TY, Lee MC. ATPase family AAA domain containing 3A is an anti-apoptotic factor and a secretion regulator of PSA in prostate cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2011;28:9–15. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hubstenberger A, Labourdette G, Baudier J, Rousseau D. ATAD 3A and ATAD 3B are distal 1p-located genes differentially expressed in human glioma cell lines and present in vitro anti-oncogenic and chemoresistant properties. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:2870–2883. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith JS, Alderete B, Minn Y, et al. Localization of common deletion regions on 1p and 19q in human glioma and their association with histological subtype. Oncogene. 1999;18(28):4144–4152. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stupp R, Hegi ME, van den Bent MJ, et al. Changing paradigms—an update on the multidisciplinary management of malignant glioma. Oncologist. 2006;11(2):165–180. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-2-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Remmele W, Schicketanz KH. Immunohistochemical determination of estrogen and progesterone receptor content in human breast cancer. Computer-assisted image analysis (QIC score) vs. subjective grading (IRS) Pathol Res Pract. 1993;189:862–866. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)81095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Challberg MD, Kelly TJ., Jr. Adenovirus DNA replication in vitro: origin and direction of daughter strand synthesis. J Mol Biol. 1979;135(4):999–1012. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90524-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ambrose M, Goldstine JV, Gatti RA. Intrinsic mitochondrial dysfunction in ATM-deficient lymphoblastoid cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(18):2154–2164. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tentori L, Portarena I, Torino F, Scerrati M, Navarra P, Graziani G. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor increases growth inhibition and reduces G(2)/M cell accumulation induced by temozolomide in malignant glioma cells. Glia. 2002;40:44–54. doi: 10.1002/glia.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliva CR, Nozell SE, Diers A, et al. Acquisition of temozolomide chemoresistance in gliomas leads to remodeling of mitochondrial electron transport chain. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:39759–39767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.147504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le Calvé B, Rynkowski M, Le Mercier M, et al. Long-term in vitro treatment of human glioblastoma cells with temozolomide increases resistance in vivo through up-regulation of GLUT transporter and aldo-keto reductase enzyme AKR1C expression. Neoplasia. 2010;12:727–739. doi: 10.1593/neo.10526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen J, Emara N, Solomides C, Parekh H, Simpkins H. Resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy in lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66(6):1103–1111. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1268-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng HB, Parekh HK, Chow KC, Simpkins H. Increased expression of dihydrodiol dehydrogenase induces resistance to cisplatin in human ovarian carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15035–15043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hung JJ, Chow KC, Wang HW, Wang LS. Expression of dihydrodiol dehydrogenase and resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy in adenocarcinoma cells of lung. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:2949–2955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eaton JS, Lin ZP, Sartorelli AC, Bonawitz ND, Shadel GS. Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated kinase regulates ribonucleotide reductase and mitochondrial homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(9):2723–2734. doi: 10.1172/JCI31604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watters D, Kedar P, Spring K, et al. Localization of a portion of extranuclear ATM to peroxisomes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(48):34277–34282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Han YR, Plummer MR, Herrup K. Cytoplasmic ATM in neurons modulates synaptic function. Curr Biol. 2009;19(24):2091–2096. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cascone A, Bruelle C, Lindholm D, Bernardi P, Eriksson O. Destabilization of the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes by core and linker histones. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rone MB, Midzak AS, Issop L, et al. Identification of a dynamic mitochondrial protein complex driving cholesterol import, trafficking, and metabolism to steroid hormones. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26(11):1868–1882. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meador JA, Zhao M, Su Y, Narayan G, Geard CR, Balajee AS. Histone H2AX is a critical factor for cellular protection against DNA alkylating agents. Oncogene. 2008;27(43):5662–5671. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rabinowitz JD, White E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science. 2010;330:1344–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1193497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ha HC, Snyder SH. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is a mediator of necrotic cell death by ATP depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(24):13978–13982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]