Abstract

Recurrent event data are largely characterized by the rate function but smoothing techniques for estimating the rate function have never been rigorously developed or studied in statistical literature. This paper considers the moment and least squares methods for estimating the rate function from recurrent event data. With an independent censoring assumption on the recurrent event process, we study statistical properties of the proposed estimators and propose bootstrap procedures for the bandwidth selection and for the approximation of confidence intervals in the estimation of the occurrence rate function. It is identified that the moment method without resmoothing via a smaller bandwidth will produce a curve with nicks occurring at the censoring times, whereas there is no such problem with the least squares method. Furthermore, the asymptotic variance of the least squares estimator is shown to be smaller under regularity conditions. However, in the implementation of the bootstrap procedures, the moment method is computationally more efficient than the least squares method because the former approach uses condensed bootstrap data. The performance of the proposed procedures is studied through Monte Carlo simulations and an epidemiological example on intravenous drug users.

Keywords: bootstrap, independent censoring, intensity function, kernel estimator, Poisson process, rate function, recurrent events

1. Introduction

Recurrent event data are frequently encountered in longitudinal follow-up studies when study individuals experience multiple events repeatedly over time. In this paper, we consider recurrent events of the same type, and develop methods and theory of smoothing procedures for estimating the rate function of recurrent event processes.

Recurrent event data are largely characterized by the rate function. In the regression context, semi-parametric marginal rate models were considered by Pepe & Cai (1993) and score equations were proposed for the estimation of regression parameters. Lin et al. (2000) further provided a rigorous justification of the marginal model through the empirical process theory. Recent work on the estimation of the cumulative rate function, which is formulated in the framework of counting processes, can be tracked back to the paper of Nelson (1988). Under the Poisson process assumption, Bartoszyński et al. (1981) considered a class of smoothing methods to estimate the rate function. In their theoretical development, the censoring times are assumed to be pre-fixed constants. For recurrent event data without the Poisson assumption, Lawless & Nadeau (1995) and Nelson (1995) studied non-parametric procedures for estimating the cumulative rate function and developed the corresponding robust variance estimates. Although counting process methods for estimating the cumulative rate function have been thoroughly studied, smoothing techniques for estimating the rate function have never been rigorously developed or studied without the Poisson assumption.

Let N(t) denote the recurrent event process in a finite interval [0, T0], where T0 is a positive constant. The rate function of a continuous recurrent event process at t, t ∈ [0, T0], is defined as

Note that the definition of the rate function is different from the conventional intensity function where the intensity function is defined as the occurrence probability of recurrent events conditional on the event history up to t. The rate function is defined as the population average of occurrence probability of recurrent events at time point t unconditionally on the event history. Because its marginal interpretation is useful for risk factor comparison, the rate function is preferred to the intensity function as the tool for analysis in many public health and biomedical applications.

Suppose the data are collected from n independent subjects experiencing recurrent events and the observation of recurrent events from each subject could be terminated due to loss of follow-up or end of the study. For the ith subject, let Ni(t) denote the recurrent event process in [0, T0], and let Yi, 0 ≤ Yi ≤ T0, be the censoring time at which the observation of Ni(t) is terminated. In this paper, we propose smoothing methods of the rate function under the following model assumption:

(A1) Each recurrent event process {Ni(t)} satisfies E [dNi(t)|δi(t)] = δi(t)λ(t)dt, where δi(t) = 1[yi≥t] is the at risk indicator.

Note that the above model is also a model of Lin et al. (2000), and Scheike (2002) without considering covariates. As one can see, assumption (A1) is a practically unrestrictive assumption which does not place any specific distributional condition (e.g. Poisson assumption) on the recurrent event process. Based on the above model, we develop the moment and least squares methods for estimating the rate function and study the properties of the proposed estimators. In addition, bootstrap procedures are proposed to establish the criteria for bandwidth selection and to construct the practical confidence intervals for the rate function. In this study, the pros and cons of these two estimation methods are identified and explored. First, unlike the moment method, the least squares method does not produce estimates with nicks occurring in the curve at the censoring times. Secondly, under some regularity conditions, the asymptotic variance of the least squares estimator is smaller than that of the moment estimator. Thirdly, in the implementation of bootstrap procedures, the bootstrap analogue of the moment estimator can be computed via the condensed bootstrap data instead of the original raw data, and is thus faster in computation. The contents of this paper are organized as follows: section 2 introduces the moment and least squares methods for the estimation of the rate function. In section 3, we propose bootstrap procedures for selecting bandwidths and constructing practical confidence intervals. Section 4 establishes asymptotic properties of the proposed estimators and the corresponding bootstrap analogues. The consistency properties of the estimators for bias correction are also derived in this section. Monte Carlo simulations are conducted in section 5 to examine the performance of the proposed procedures. In section 6, the methods are applied to data collected in an intravenous drug user study. A discussion of the estimation methods will be provided in section 7.

2. Estimation methods

In this section, two types of smoothing estimation methods for λ(t) are proposed. To avoid edge effects in the boundary region, the lth order boundary kernel weight function of Gasser & Müller (1978) with adjustment for the censoring time is used in our estimation procedures. The reason for doing so is mainly to reduce and estimate the bias terms in the proposed estimators. In the next section, we will use the difference of the second order and the fourth order kernel estimators to estimate the dominant biases of the proposed second order kernel estimators.

The first kernel estimator, which is the improvement of the window type estimation of Bartoszyński et al. (1981), is given by

| (1) |

where Ks,l(·) is the lth order boundary kernel function with adjustment for s, ht is a positive valued bandwidth, δ.(t) = δi(t), T0 is the maximum value of the censoring times or the recurrent event times, and the term ξi(t) = (δi(t) KYi,2((t − u)/ht)dNi(u)) in (1) is an estimator of the subject-specific rate function λi(t) for t in the interval [0, Yi]. Similar to estimators considered by Ramlau-Hansen (1983), Tanner & Wong (1983) and Yandell (1983) for intensity or hazard function, another estimator is obtained by smoothing the Nelson–Aalen type estimator (t) = (δi(u)/δ.(u))dNi(u) as below,

| (2) |

As (t) can also be obtained by minimizing the sum of the squares

with respect to λ(t), it herein is called the least squares estimator of λ(t).

Note that (t) is computed by smoothing the empirical subject-specific rate estimator, whereas (t) takes the average of the subject-specific rate smoothers. The least squares method produces a smooth curve but the moment estimator has some nicks occurring at the censoring times. To avoid the problem of nicks, the estimated curve can be re-smoothed by using a smaller bandwidth. When there is no censoring on the recurrent event processes (i.e. the censoring times equal a pre-fixed constant), it is easy to see that these two estimators are the same. In the succeeding sections, we will investigate the properties of (t) and (t) through the empirical process theory of recurrent event processes.

3. Bootstrap methods

In this section, we will propose and study the bootstrap analogues of the two kernel estimators. As subjects are independently selected, a natural bootstrap sampling scheme following the work of Efron (1979) is to re-sample the entire measurements yi = {(Ni(·), Yi} of each subject with replacements from the original data. Let {} denote the bootstrap sample of {y1, … ,yn}. Then, the bootstrap analogues, say, (t) and (t) of (t) and (t) are computed based on the bootstrap sample.

It can be seen that (t) can be directly computed from the condensed bootstrap data {}, which is the bootstrap data of {u1(t), …, un(t)} with ui(t) = (ξi(t), δi(t)). In contrast, (t) needs to be computed from the raw longitudinal bootstrap sample {}. Therefore, the bootstrap estimator (t) requires more computational time and memory space than those for the bootstrap estimator (t). In the succeeding subsections, the bootstrap analogues will be used in the bandwidth selection and the construction of approximated confidence intervals.

3.1. Bandwidth selection

Conditioning on the recurrent event data, the bootstrap analogues (t) and (t) both can be shown to be the approximately unbiased estimators of (t) and (t). Thus, these bootstrap estimators fail to mimic the biases of the estimators because the bootstrap bias is relatively negligible. To remedy this problem, the bias correction of Schucany (1995), using the difference of the second and the fourth order kernel estimators, is extended in this case to approximate the biases of (t) and (t) by

| (3) |

In practical implementation, Ks,l((t − u)/ht) is often assigned to be Ks,l((t − u)/ht) = h−1 1(s, (t − u)/ht) K((t − u)/ht) with αl(s, u) and K(·) being separately the (l − 1)th polynomial function of u and a symmetric density. The dominant bias term of each estimator at each time t can be estimated by using the estimators in equation (3) at the specified bandwidths as Schucany (1995). Under the considered data setting, we find that the method performs well in the numerical studies. Using the estimated dominant bias terms, say, and for the bias adjustment and the sample variances of the bootstrap estimators, it is reasonable to approximate the mean squared errors, say, mse((t)) and mse((t)) of (t) and (t), respectively, by

| (4) |

where Vnb(·) denotes the sample variance of a bootstrap estimator. The local bandwidth estimators, say, and at time t are then defined to be the minimizers of msenb((t)) and msenb((t)). Moreover, the global bandwidth estimators for (t) and (t) can be obtained by minimizing the mean integrated squared errors

| (5) |

where h is a positive time-independent bandwidth and π(t) is a non-negative weight function. Generally, the mean integrated squared errors provide a variety of global distance measures to investigate the accuracy of the considered estimator. In implementation, the weight function π(t) is often assigned to be a uniform density function.

3.2. Confidence intervals

For the construction of confidence intervals, it is well known that the plug-in asymptotic procedure often provides poor estimates. Here, the bootstrap method is considered to be a good alternative for the construction of confidence intervals. The basic idea is to use the empirical distributions of the bootstrap quantities to approximate the sampling distributions of the corresponding estimators. The validity of the proposed procedures will be verified in the next section. The bootstrap procedure for the moment method below describes the steps for constructing the approximated (1 − α) pointwise and simultaneous confidence intervals for λ(t) with bias correction.

-

1.1

Draw the bootstrap sample {} of size n with replacement from the condensed data {u1, …, un}.

-

1.2

Compute the bootstrap estimator (t) and (t) = (t) − (t) based on the condensed bootstrap data drawn in step 1.1.

-

1.3

Repeat steps 1.1–1.2 B times, and compute the standard errors and the percentiles of B bootstrap estimators (t) and (t), and Mnb() = supt∈Υ |(t)/senb((t))|, where senb(·) denotes the standard error of bootstrap estimators and Υ is a time period.

-

1.4Construct separately the approximated (1 − α) pointwise and simultaneous confidence intervals for λ(t) via

and(6)

Here, (·) is the pth quantile of B bootstrap estimators.(7)

As an alternative to the above bootstrap percentile intervals in step 1.4, one can also use separately the pointwise and simultaneous intervals of the forms

and

where z(1−α/2) is the (1 − α/2) quantile value of the standard normal distribution. As for the least squares method, we first re-sample the entire measurements yi of each subject with replacement from the original data {y1, …, yn}, and then compute the bootstrap estimator (t) based on the bootstrap data {}. Same with steps 1.2–1.4, the approximated (1 − α) pointwise and simultaneous confidence intervals for λ(t) are constructed via substituting (t), (t) and (t) for (t), (t) and (t), respectively.

4. Asymptotic properties

We assume the following regularity conditions for the rest of this paper:

-

(A2)

Yis are independent and identically distributed with the cumulative distribution function FY(y) and the probability measure PY(y).

-

(A3)

λ(t) is four times differentiable and bounded with λ(t) > λ0 for some positive constant.

-

(A4)

E[dN(u)dN(v)dN(w)] ≤ c0dudvdw for some positive constant c0 and for all u, v, w ∈ [0, T0].

-

(A5)

Define Ϛv(t, ht, s) = |α2(s, u)K(u)|vdu with Ϛ3(t, ht, s) < ∞.

-

(A6)

ht = n−1/5h0t (or h = n−1/5h0) for some positive bounded constant h0t(h0).

Let ζi(t) = KT0,2((t − u)/ht)(δi/(1 − FY(u)))(u)dNi(u). By the law of large numbers, it be can shown that

| (8) |

Thus, the kernel estimators (t) and (t) can be expressed as

| (9) |

and

| (10) |

Before establishing theorem 1, a technical lemma is stated below.

Lemma 1

Suppose that assumptions (A1)–(A6) and FY(T0) < 1 are satisfied. Then,

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

and

| (14) |

where

with β2,2(t, ht, s) = u2α2(s, u)K(u)du and γv(t, ht, s) = (α2(s, u)K(u))νdu for ν = 2, 3.

Proof. See appendix.

Let Φ(·) denote the cumulative distribution function of the univariate standard normal distribution. The asymptotic normalities of the estimators are established in the following theorem.

Theorem 1

Suppose that assumptions (A1)–(A6), and FY(T0) < 1 are satisfied. Then, for all z ∈ R and n → ∞,

| (15) |

and

| (16) |

where

Proof. See appendix.

When the estimators are computed based on a linear function and a symmetric density separately for α2(·) and K(·), it can be derived algebraically that (t) ≥ (t) as h converges to 0. In addition, if the distribution of the censoring time is continuous and the kernel function is assigned without boundary adjustment, paralleling the proof of theorem 1, these two estimators can be shown to have the same asymptotic bias and variance. As for the assumptions on the recurrent event process, the variances of (t) and (t) under the under the general empirical process assumptions may not be equal to those Poisson-type assumption. However, each estimator has the same asymptotic variance with or without the Poisson assumption. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that the kernel smoothers are locally smooth and the event history information carried in the kernel smoothers is ignorable; thus, the asymptotic variances of the estimators are mainly dominated by the rate function λ(t) regardless of the correlation structure on the recurrent event process.

In the next lemma, we state the consistency of the estimators (t) and (t). The properties can be derived directly by using lemma 1 and a similar proof procedure to that of theorem 1.

Lemma 2

Suppose that assumptions (A1)–(A3) and (A6), and FY(T0) < 1. Then, as n → ∞,

| (17) |

Before deriving the asymptotic normalities of the bootstrap estimators, let Pnb(·) denote the probability measure conditioning on the sample {y1, …, yn}. The next theorem and lemma 2 show the validity of the approximated bootstrap confidence intervals in section 3.2, i.e. the sampling distributions of ((t) − (t)) and ((t) − (t)) can be used to approximate the distributions of ((t) − λ(t) − (t)) and ((t) − λ(t) − (t))

Theorem 2

Suppose that assumptions (A1)–(A6), and FY(T0) < 1 are satisfied. Then, for all z ∈ R and n → ∞,

| (18) |

and

| (19) |

Proof. See appendix.

Before showing the validity of the bootstrap simultaneous confidence intervals in section 3.2, the condition, ((nh)−1 + h)(ln (n))4 → 0 as n → ∞, is examined first. It is indicated from assumption (A6) that the bandwidth selection satisfies this requirement. As for the function K(·), the Gaussian kernel density function will be assigned in estimation and is shown to satisfy the assumptions of Jhun (1988). Using the expressions in (9) and (10) with global bandwidth h, and paralleling the proof of Hall (1993), one can show that the sampling distributions of Mnb() and Mnb() can be used to approximate the distributions of M() = supt∈Υ |((t) − λ(t) − b1,h(t))/σ1,h(t)| and M() = supt∈Υ |((t) − λ(t) − b2,h(t))/σ2,h(t)| respectively.

Theorem 3

Suppose that assumptions (A1)–(A6), and FY(T0) < 1 are satisfied. Then, for all z ∈ R+ and n → ∞,

| (20) |

and

| (21) |

5. Monte Carlo simulations

In this numerical study, we simulate data from subject-specific non-stationary Poisson processes. Note that, due to the independent increment property of Poisson processes, the intensity function of a Poisson process is also the rate function. Assume that, given the value of the random variable Zi, Ni(t) is a non-stationary Poisson process which has the following subject-specific rate (or intensity) functions:

In the above additive and multiplicative models, the random variable Zi can be considered as the random effect or frailty, and is designed to be distributed as the uniform distribution U(0.9, 1.1). Thus, both of the rate functions are equal to

The simulated data are generated from 450 independent non-stationary Poisson processes {Ni(t)} with recurrent event times ranging from 0 to 4. Moreover, the censoring times are set to be distributed as

Here, the assumed conditions are similar in nature to those found in the intravenous drug user study which will be studied in the next section. The simulation process is repeated 500 times. For each simulated data set, the kernel estimators (t) and (t) are computed by (1) and (2) with the normal density for K(·). Moreover, the local and global optimal bandwidths are selected separately via the bootstrap mean squared errors in (4 and 5). The 500 simulation averages of both estimated curves with bias correction are very close to the true rate function. Here, we find that the bias correction improves the accuracy of both estimators, and the variation of (t) is smaller than that of (t) although the difference is not apparent. To evaluate the validity of the estimators, the approximated 95% bootstrap confidence intervals are constructed based on 200 bootstrap replications at 39 equally spaced time points within the period (0, 4). As the performances of both methods are comparable, we present only the empirical coverage probabilities of the moment estimation method. Table 1 summarizes the empirical coverage probabilities of 95% pointwise confidence intervals for λ(t) at selected time points and different bandwidths. It is shown that the coverage probabilities for the procedures constructed using the optimal local bandwidths are generally close to the nominal level. However, poor coverage probabilities appear at extremely small or large bandwidths. The same conclusion can also be drawn for the empirical coverage probabilities of 95% simultaneous confidence intervals for λ(t) in Table 2.

Table 1. The empirical coverage probabilities of the 95% pointwise bootstrap confidence intervals for λ(t), based on the moment estimation method.

| Time point | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Case 1) | 0.956 | 0.914 | 0.918 | 0.928 | 0.938 | 0.956 | 0.986 |

| ht, = 0.05 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| ht, = 0.37 | 0.852 | 0.806 | 0.830 | 0.796 | 0.824 | 0.868 | 0.910 |

| (Case 2) | 0.954 | 0.920 | 0.940 | 0.946 | 0.926 | 0.942 | 0.976 |

| ht = 0.05 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.996 | 1.000 |

| ht = 0.37 | 0.846 | 0.816 | 0.848 | 0.692 | 0.828 | 0.842 | 0.898 |

Table 2. The empirical coverage probabilities of the 95% simultaneous bootstrap confidence intervals for λ(t), based on the moment estimation method.

| Time period | (0,4) | [0.5, 3.5] | [1.0, 3.0] | [1.5, 3.5] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Case 1) | 0.986 | 0.970 | 0.972 | 0.958 |

| h = 0.05 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| h = 0.37 | 0.660 | 0.514 | 0.538 | 0.592 |

| (Case 2) | 0.986 | 0.968 | 0.960 | 0.968 |

| h = 0.05 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| h = 0.37 | 0.638 | 0.550 | 0.588 | 0.650 |

6. A data example

The data set used here involves 450 HIV-negative intravenous drug users who entered the study before 1 August 1993 from the AIDS Link to Intravenous Experiences cohort study. This study was initiated in 1988 and started to systematically collect health service data in July 1993. The repeated hospitalizations for each drug user here were observed between 1 August 1993 and 31 December 1997. Details of this study can be found in Vlahov et al. (1991).

Let yi be the time length from 1 August 1993 to the date of the last visit for the ith drug user, and T0 the maximum time of yis. Among these patients, the median of the number of recurrent events is 1 and the number ranges from 0 to 19. The mean of the censoring time is 3.734 years and the censoring time ranges from 0.275 to 4.394 years. The main objectives of our analysis are to estimate the rate function of hospitalizations over time for HIV-negative drug users and to evaluate the accuracy of the estimated curve.

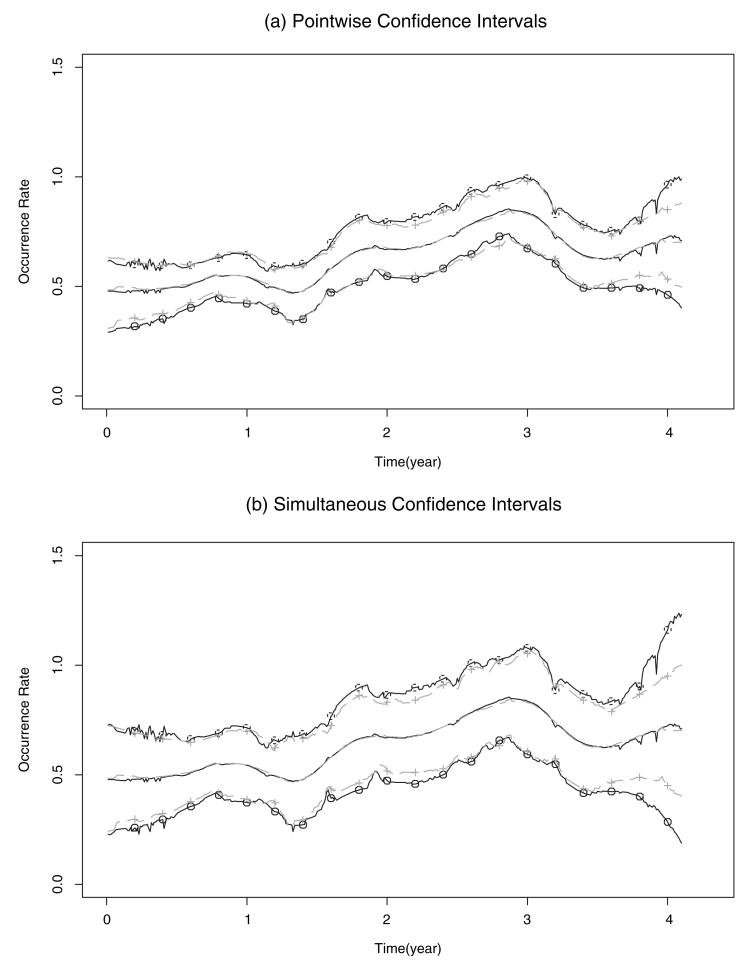

In this study, two estimators are computed based on the Gaussian kernel density for K(·). For the bandwidth selection, the bootstrap mean squared errors in (4) and (5) are used separately to select local and global optimal bandwidths for (t) and (t). Moreover, the corresponding 95% pointwise and simultaneous confidence intervals of the hospitalization rate estimators are computed at 430 equal spaced time points within the period (0, 4.31). It appears in Figs. 1(a),(b) that both the estimated curves (t) and (t) imply the same biological explanation except wider confidence intervals for the moment method. From the figures, we can see that the hospitalization occurence rates are lower than 1 and the peak of the curve occurs in about the later half of the study. This might indicate that the intravenous drug users received some medical intervention during the study period, and, hence, tend to have a decreasing trend in frequencies of hospitalization.

Fig. 1.

The solid and dashed curves represent respectively the estimated rate functions (t) and (t) of HIV-negative intravenous drug users with the corresponding 95% bootstrap intervals indicated by o and +.

7. Discussion

In this study, two smoothing methods are proposed for the estimation of the rate function under the independent censoring model without the Poisson assumption on the recurrent event process. We have pointed out that the moment estimator has the disadvantage of having nicks in the estimates. When a linear function and a symmetric density are designed for the second order kernel smoother, the asymptotic variance of the moment estimator is shown to be larger than that of the least squares estimator, although the differences are expected to be small. Regardless of these disadvantages, the moment estimation possesses important computational advantages as we discussed in section 3. In general, when sample size (n) is appropriate, the drawbacks of the moment estimator appear insignificant and the computational advantage becomes an attractive feature for adopting the moment estimation approach.

Acknowledgements

The first author’s research was partially supported by the National Science Council grant 9-2118-M-002-001 (Taiwan), and the second author’s research was partially supported by the National Institute of Health grants CA098252 (USA). We would like to thank the referee for valuable comments. We are also grateful to Dave Vlahov and Strathdee at Johns Hopkins University for providing the anonymous ALIVE data. Provision of the data was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants DA04334 and DA08009.

Appendix

Proof of lemma 1

In the following proof, we only derive the statements of (11) and (13). Same arguments can be used in the derivation of (12) and (14). By assumptions (A1)–(A3) and the Taylor expansion, we can get

| (22) |

E[(t)] can be decomposed into two components:

| (23) |

where

and

By assumptions (A1)–(A3), we can show that

| (24) |

Assumption (A4) implies that there exists a positive constant c1 such that

| (25) |

Substituting (24) and (25) into (23), E[(t)] is obtained. Along the same lines as the derivation of E[(t)], statement (15) for v = 3 follows.

Proof of theorem 1

From (9), we make the linear approximation

| (26) |

By the Berry–Esséen theorem, we obtain the following inequality:

| (27) |

where d is a positive constant independent of n and ξi(t). As |ξi(t)| ≤ ηi(t) and Ni(t)s are positive random variables, it implies that

| (28) |

where ηi(t) = δi |Kti,2((t − u/ht)|dNi(u). Similar to the derivation of lemma 1, we can obtain, for v = 1, 2, 3,

| (29) |

From (28), (29) and lemma 1, we can imply

| (30) |

By assumption (A6) and substituting (30) into (27), we derive

| (31) |

Finally, the proof of (15) is completed by (26) together with (31),

| (32) |

and

| (33) |

For the proof of (16), we first make the linear approximation

| (34) |

Then, paralleling the steps from (27–31) with (34),

| (35) |

and

| (36) |

the asymptotic normality of (t) is obtained.

Proof of theorem 2

As the derivation of the proof for the bootstrap estimator (t) is similar those of (t), for the space of presentation, we derive only the asymptotic normalities of (t). Let (t) = (t) K,2((t − u)/ht)d(u). By the law of large numbers, we can show that, for any ε > 0,

| (37) |

Then, the bootstrap kernel (t) can be expressed as

| (38) |

Similar to the proof of theorem 1, we can derive that

| (39) |

In addition, by the Berry–Esséen theorem, there exists a positive constant c2 such that

| (40) |

As

| (41) |

by the law of large numbers and lemma 1, it implies

| (42) |

and

| (43) |

Substituting (42) and (43) into (41), we get

| (44) |

Contributor Information

CHIN-TSANG CHIANG, Department of Mathematics, National Taiwan University.

MEI-CHENG WANG, Department of Biostatistics, Johns Hopkins University.

CHIUNG-YU HUANG, Division of Biostatistics, University of Minnesota.

References

- Bartoszyński R, Brown BW, McBride CM, Thompson JR. Some nonparametric techniques for estimating the intensity function of a cancer related nonstationary Poisson process. Ann. Statist. 1981;9:1050–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Ann. Statist. 1979;7:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gasser Th., Müller H-G. In: Kernel estimation of regression functions. Smoothing techniques for curve estimation. Gasser Th., Rosenblatt M., editors. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1979. pp. 23–68. Spring Lecture Notes in Mathematics No. 757. [Google Scholar]

- Hall P. On edgeworth expansion and bootstrap confidence bands in nonparametric curve estimation. J. Roy. Statist. Soc. Ser. B. 1993;55:291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Jhun M. Bootstrap density estimates. Comm. Statist. Theory Methods. 1988;17:61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lawless JF, Nadeau C. Some simple robust method for the analysis of recurrent events. Technometrics. 1995;37:158–168. [Google Scholar]; Lin, Fleming TR. Springer-Verlag; New York: pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Wei LJ, Yang I, Ying Z. Semiparametric regression for the mean and rate functions of recurrent events. J. Roy. Statist. Soc. Ser. B. 2000;62:711–730. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson WB. Graphical analysis of system repair data. J. Qual. Technol. 1988;20:24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson WB. Confidence limits for recurrence data – applied to cost or number of product repairs. Technometrics. 1995;37:147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS, Cai J. Some graphical displays and marginal regression analyses for recurrent failure times and time dependent covariates. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 1993;88:811–820. [Google Scholar]

- Ramlau-Hansen H. Smoothing counting process intensities by means of kernel functions. Ann. Statist. 1983;11:453–466. [Google Scholar]

- Schucany WR. Adaptive bandwidth choice for kernel regression. J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 1995;90:535–540. [Google Scholar]

- Scheike TH. The additive nonparametric and semiparametric Aalen model as the rate function for a counting process. Lifetime Data Anal. 2002;8:229–246. doi: 10.1023/a:1015849821021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner MA, Wong WH. The estimation of the hazard function from randomly censored data by the kernel method. Ann. Statist. 1983;11:989–993. [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Anthony JC, Munñov A, Margolick J, Nelson KE, Celentano DD, Solomon L, Polk BF. The ALIVE study: a longitudinal study of HIV-1 infection in intravenous drug users: description of methods. J. Drug Issues. 1991;21:759–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yandell BS. Nonparametric inference for rates with censored survival data. Ann. Statist. 1983;11:1119–1135. [Google Scholar]