Abstract

Camptodactyly-arthropathy-coxa vara-pericarditis (CACP) syndrome is an inherited disorder characterized by congenital or early-onset flexion camptodactyly, childhood-onset of non-inflammatory arthropathy, often associated with non-inflammatory pericarditis or pericardial effusion and progressive coxa vara. The causative gene is located on chromosome band 1q25-31. This gene encodes for “proteoglycan-4” (PRG-4), which is a surface lubricant for joints and tendons. This syndrome has distinct radiological and histological features, which are important to recognize since it may clinically mimic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and mutation studies may not be easily available. We describe a case of a 3-year 3-month-old female with features of CACP syndrome.

Keywords: Camptodactyly-arthropathy-coxa vara-pericarditis syndrome, intraosseous fluid-filled herniations, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, no joint erosions

INTRODUCTION

Camptodactyly-arthropathy-coxa vara-pericarditis (CACP) syndrome is a genetic disorder caused by mutation in the Proteoglyacn PRG4 gene on chromosome 1 (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man OMIM number 208250).[1]

The syndrome is characterized by congenital or early-onset camptodactyly and childhood-onset of non-inflammatory arthropathy, coxa vara deformity, or other dysplasia associated with progressive hip disease and non-inflammatory pericardial effusion. It has an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance and the causative gene is located on chromosome band 1q25-31.[2,3]

We present a case of a female child who presented with early onset camptodactyly, non-inflammatory arthropathy, short femoral necks, with distinctive features on biopsy and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), without pericarditis or pericardial effusion.

CASE REPORT

A 3-year 3-month-old child presented with a 4-month history of swelling of both knees and wrists. The parents also stated that they had noticed bent fingers for nearly one and a half years. On examination, the patient had camptodactyly of the fingers with swelling of both knees and wrists without restricted motion or signs of inflammation like erythema or tenderness. Systemic examination showed no evidence of fever, lymphadenopathy, skin rash, or other systemic features. Her sibling and parents were normal on physical examination. Routine blood work-up revealed normal hemogram, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) with negative Antinuclear Antibody (ANA).

Anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of pelvis revealed a broad short femoral neck and coxa vara [Figure 1]. The articular surfaces were smooth with no erosions. X-ray of the hand was not obtained. X-ray of the knee revealed bilateral effusions with osteopenia and no erosions [Figure 2]. MRI of the hip showed a large joint effusion and intraosseous fluid-filled herniations affecting the acetabulum with intra-articular connection [Figure 3a]. The synovium was mildly thickened and showed enhancement, better appreciated on the left side [Figure 3b]. Conspicuously, t9/21/2013here was absence of cartilage destruction. Knee MRI showed large amount of joint fluid [Figure 4a] with mildly thickened enhancing synovium [Figure 4b].

Figure 1.

Three-year 3-month-old girl child with CACP syndrome. Anteroposterior radiograph of pelvis shows smooth flattening of femoral heads with irregular acetabulae (arrows). Bilateral femoral necks appeared short and broad with coxa vara (double arrows).

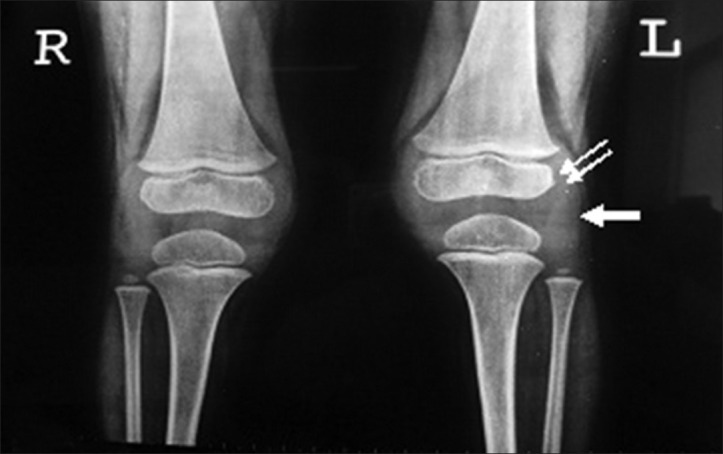

Figure 2.

Three-year 3-month-old girl child with CACP syndrome. Plain AP radiograph of both knees shows periarticular osteopenia, apparent widening of the joint space the result of effusions (arrow) and enlargement of the epiphyses secondary to the hyperaemia (double arrows). Note the absence of joint erosions.

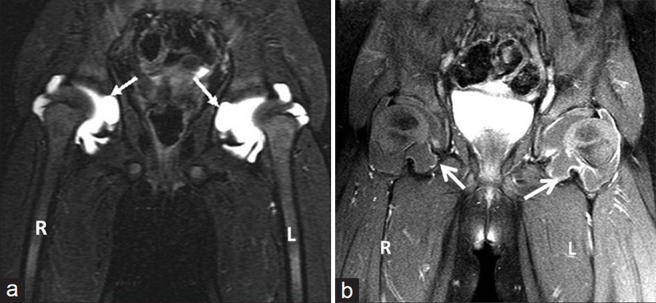

Figure 3.

(a) Three-year 3-month-old girl child with CACP syndrome. Coronal STIR image of hips (on 3T system) shows large bilateral joint effusions. Note the intra-osseous acetabular herniations communicating with the effusions (arrows) and (b) 3-year 3-month-old girl child with CACP syndrome. Coronal T1-weighted image of hips (on 3T system) obtained after administration of gadolinium shows rim enhancement of joint capsule (better appreciated on the left side) and of walls of intraosseous herniations (arrows). Note the lack of thick solid synovial enhancement as seen in Juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Figure 4.

(a) Three-year 3-month-old girl child with CACP syndrome. Coronal STIR image of both knees (on 3T system) shows large effusions. Small intraosseous cysts are identified along the medial femoral condyle (arrows) and (b) 3 year 3 month old girl child with CACP syndrome. Coronal T1 weighted of both knees (on 3T system) shows effusion with mildly thickened synovium (arrows).

A synovial biopsy was done. This revealed hyperplasia of synovium without inflammatory cells. There was evidence of giant cell infiltration, which expressed CD 68 on immunohistochemistry.

Ancillary investigations like-2 Dimensional (2D) echocardiography carried out did not reveal effusion or pericarditis. Chest radiography was normal. The echocardiogram was normal.

DISCUSSION

CACP syndrome, first described in 1984, is characterized by congenital or early-onset camptodactyly, childhood-onset non-inflammatory arthropathy associated with synovial hyperplasia, progressive coxa vara deformity, and non-inflammatory pericardial or pleural effusion.

It is an autosomal recessive condition caused by loss of function mutations in the Proteoglycan-4 (PRG4) gene, leading to absence of lubricin in the synovial fluid and accumulation of synovial fluid in the joint spaces.[4]

Marcelino et al., (1999) identified the PRG4 gene within the chromosome 1q25-q31 as the critical region for the autosomal recessive CACP syndrome (Phenotype number 208250).[5]

Children with CACP syndrome often present with camptodactyly (bent fingers) and swollen joints with preserved range of motion without other signs of inflammation.

Camptodactyly is a universal finding in patients with CACP and is usually bilateral and congenital, but may develop in early childhood. Squaring or flattening of the metacarpal and phalangeal heads can be seen on radiograph of the hand.

Arthropathy principally involves large joints such as elbows, hips, knees, and ankles. Radiologic findings include periarticular osteopenia without associated erosions.

Coxa Vara with short femoral necks is seen on radiograph of hips. The hallmark of this condition is intra-osseous fluid-filled herniations affecting the acetabulum that is seen on conventional radiographs as benign radiolucent acetabular lesions. These herniations and intra-articular communications are best identified on MRI. There is mild synovial thickening and rim-like enhancement of the fluid-filled bursae.[6] The presence of coxa vara is variable with studies reporting figures between 50% and 90%.

Pericarditis is a variable finding and has been reported in up to 30% of CACP, and it may be mild and self-limited.

Laboratory investigations including ESR, CRP, and full blood count are normal in patients with CACP syndrome.

Synovial fluid in this condition is clear, honey-coloured, and low in cell count. The synovial histology shows little or no mononuclear infiltration, but there is a typically described multinucleated giant cells infiltration.[6] Giant cells have been identified as macrophage in origin based on CD68 expression and electron microscopic features of macrophages.[7]

Studies involving synovial fluid examination from a patient with CACP showed that hyaluronic acid molecules adopted an extended and more rigid conformation, suggesting that synovial fluid lacking lubricin would be less able to dissipate the energy of impact that occurs during motion. Jay et al., (2007) concluded that lubricin provides a chondroprotective feature to synovial fluid that is distinct from the role lubricin plays at the cartilage surface as a boundary lubricant.[8]

This condition must be distinguished from juvenile idiopathic arthritis since the management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) requires anti-inflammatory drugs, often with methotrexate and steroids owing to the inflammatory nature of the disease, whereas CACP syndrome does not respond to these drugs and is treated symptomatically and with physiotherapy.

JIA has been classified by the International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) into:

Systemic onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA): Arthritis in one or more joints with or preceded by fever of at least 2-weeks duration, documented daily for at least 3 days accompanied by one or more of the following: Evanescent (non-fixed) erythematous rash, generalized lymph node enlargement, hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly, and serositis

Oligoarthritis: Arthritis affecting one to four joints during the first 6-months of the disease, with the Persistent type affecting not more than four joints throughout the disease course, while the Extended type affects a total of more than four joints after the first 6-months of the disease

Polyarthritis (Rheumatoid Factor (RF) Negative): Arthritis affecting five or more joints during the first 6-months of disease; RF is negative

Polyarthritis (RF Positive): Arthritis affecting five or more joints during the first 6-months of the disease; two or more tests for RF at least 3-months apart during the first 6-months of disease are positive

Psoriatic Arthritis: Arthritis with psoriasis or arthritis and at least two of the following: Dactylitis, nail pitting (onycholysis) or psoriasis in a first-degree relative

Enthesitis Related Arthritis: Arthritis with enthesitis or only arthritis/enthesitis with at least two of the following: Presence of or a history of sacroiliac joint tenderness and/or inflammatory lumbosacral pain, presence of Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA-B27) antigen, onset of arthritis in a male over 6-years of age, acute anterior uveitis, or history of ankylosing spondylitis, enthesitis-related arthritis, sacroiliitis with inflammatory bowel disease, Reiter's syndrome or acute anterior uveitis in a first-degree relative

Undifferentiated Arthritis: Arthritis that fulfills criteria in no category or in two or more of the above categories.[9]

CACP syndrome can be clinically mistaken for polyarthritic JIA or systemic JIA with pericarditis. In CACP syndrome, children usually present with a joint swelling with absence of features of inflammation and examination reveals camptodactyly. JIA is primarily an inflammatory arthritis with or without systemic involvement.

On laboratory investigations, patients with JIA have elevation of both ESR and CRP, since it is an inflammatory condition, while these parameters are normal in patients with CACP syndrome.

Radiologic features of CACP syndrome-related arthritis include those of a non-erosive arthropathy with large joint effusions. Inter-osseous herniation of the joint capsule and fluid produces fluid-filled intra-osseous cysts with enhancement of the capsule. These cysts particularly are characteristic of CACP syndrome and are not seen in JIA.

In the acute phase of JIA, imaging shows evidence of effusions and local hyperemia (due to its inflammatory nature) as initial widening of joint space, soft-tissue swelling, periarticular osteopenia, and enlargement of the epiphyses [Figure 5]. In the chronic stage, the inflammatory pannus causes destruction and leads to findings of joint erosions and joint space narrowing with eventual subluxation, dislocation and ankylosis leading to epiphyseal disturbances with resultant growth abnormalities and deformities.

Figure 5.

Three-year 3-month-old girl child with CACP syndrome. Coronal STIR image of both knees (on 3T system) shows large effusions. Small intraosseous cysts are identified along the medial femoral condyle (arrows)

The acute non-erosive phase of JIA may present with joint effusions and periarticular osteopenia [Figure 5] and hence lead to radiological confusion with CACP syndrome. However, in chronic cases of JIA cartilage destruction, erosions, and ankylosis is seen. Destruction of articular cartilage is also not seen in CACP, however, in advanced or long-standing disease, cartilage destruction may occur without erosive change. The synovial thickening seen in CACP is thin compared to the florid thickening and enhancement in JIA. The cervical spine and temporomandibular joint are typically spared in CACP.[7]

A recent in vitro study demonstrated that rehabilitative joint motion can stimulate chondrocyte PRG4 secretion, suggesting that physical therapy may aid in the resolution of the camptodactyly and be appropriate as potential therapy for the arthritis involving the other joints.[10]

CONCLUSION

CACP syndrome is an autosomal recessive syndrome characterized bycamptodactyly, arthropathy, coxa vara and pericarditis with distinct radiological and histopathological features and should be considered in juvenile patients presenting with non-inflammatory arthropathy. Increased awareness of this familial condition is required to prevent confusion with other inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions seen during childhood, particularly juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Differentiation from JIA is clinically important in view of the different management prototcol for the two conditions, and in particular, because of the possible severe side effects associated with treatment for JLA.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2013/3/1/24/114211

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Center for Biotechnology Information. Online mendelian inheritance in man: An online catalogue of human genes and genetic disorders. [Last access on 2013 Jan 22]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim .

- 2.Mannurita SC, Vignoli M, Bianchi L. Novel mutations of camptodactyly arthropathy coxa vara pericarditis (CACP) Syndrome: A study on ten Cases. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(Suppl 10):261. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi BR, Lim YH, Joo KB, Kim NS, Lee KJ, Yoo DH. Camptodactyly, Arthropathy, Coxa Vara, Pericarditis (CACP) Syndrome: A case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:907–10. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.6.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahoney D. Rare disease offers pediatric rheumatology insights: Report details genetic mutation in the joint condition camptodactyly-arthropathy-coxa vara-pericarditis. [Last updated on 2006 Jan 05];Skin and Allergy News. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcelino J, Carpten JD, Suwairi WM, Gutierrez OM, Schwartz S, Robbins C, et al. CACP, encoding a secreted proteoglycan, is mutated in camptodactyly-arthropathy-coxa vara-pericarditis syndrome. Nat Genet. 1999;23:319–22. doi: 10.1038/15496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Offiah AC, Woo P, Prieur AM, Hasson N, Hall CM. Camptodactyly-Arthropathy-Coxa Vara-Pericarditis Syndrome versus juvenile idiopathic arthropathy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:522–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shayan K, Ho M, Edwards V, Laxer R, Thorner PS. Synovial pathology in camptodactyly-arthropathy-coxa vara-pericarditis syndrome. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2005;8:26–33. doi: 10.1007/s10024-004-3035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jay GD, Torres JR, Warman ML, Laderer MC, Breuer KS. The role of lubricin in the mechanical behavior of synovial fluid. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:6194–6199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608558104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petty R, Southwood T, Manners P, Baum J, Glass D, Goldenberg J. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: 2nd revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:390–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nugent-Derfus GE, Takara T, O’neill JK, Cahill SB, Gortz S, Pong T, et al. Continuous passive motion applied to whole joints stimulates chondrocyte biosynthesis of PRG4. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:566–74. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]