Abstract

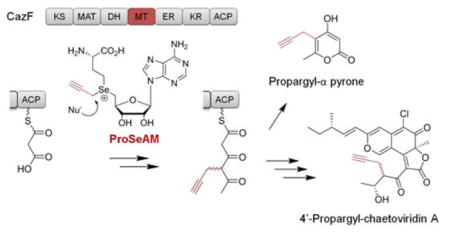

A strategy for introducing structural diversity into polyketides by exploiting the promiscuity of an in-line methyltransferase domain in a multidomain polyketide synthase in reported. In vitro investigations using the highly-reducing fungal polyketide synthase CazF revealed that its methyltransferase domain accepts the nonnatural cofactor propargylic Se-adenosyl-L-methionine and can transfer the propargyl moiety onto its growing polyketide chain. This propargylated polyketide product can then be further chain-extended and cyclized to form propargyl-α pyrone, or be processed fully into the alkyne-containing 4′-propargyl-chaetoviridin A.

S-Adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM, 1)-dependent methyltransferases are a highly versatile class of enzymes that catalyze the methylation of DNA, RNA, protein and small molecules using the sulfonium methyl group of 1.1 Remarkably, these enzymes have been shown to accept synthetic SAM analogues and can catalyze the transalkylation of their corresponding proteins,2 nucleic acids3 and small molecules4 substrates with reactive bioorthogonal functional groups. In addition to freestanding methyltransferases, methyltranserase (MT) domains can also be found within polyketide synthases (PKS) where they catalyze the α-methylation of a growing β-keto polyketide chain using 1 as the methyl-donating cofactor.5

Polyketide natural products are a structurally diverse class of molecules isolated from bacteria, fungi and plants and represent a rich source of medicinally important compounds.6 The complex structures associated with polyketides arise from the utilization of simple building blocks, such as malonyl-CoA, and can undergo varying degrees of β-keto reduction during each catalytic cycle on the PKS.7 As a result, enzyme-directed engineering approaches have been aimed at diversifying building block and starter unit selection as a way to enhance the structural variation of polyketides and to create analogues containing nonnative functional groups.8 Recently, enzyme engineering efforts with bacterial acyltransferase (AT) domains9 and acyl-CoA synthetases10 have been successful at assimilating nonnatural moieties into polyketides using synthetic malonic acid building blocks. While these synthetic biology strategies are promising for enhancing the structural diversity of polyketides, an alternative method for introducing structural variation can involve the use of nonnatural cofactors. Thus, given the reported promiscuous nature of standalone methyltransferases, we wanted to investigate whether MT domains found within PKSs could behave in the same manner and facilitate the incorporation of different alkyl groups at the α-positions of polyketides.

To examine the substrate specificity of a PKS MT domain, we turned our attention to the fungal highly-reducing PKS (HR-PKS) CazF, which is involved in the biosynthesis of the chaetoviridin and chaetomugilin azaphilones.11 In vitro reconstitution experiments with recombinant CazF (284 kDa) expressed from Saccharomyces cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA12 verified that the MT domain functions after the first chain-extending condensation step (Figure 1), and the remaining domains are all catalytically active to generate a small polyketide product.11 CazF therefore represented a good model system for exploring whether a MT domain can be used to introduce chemical diversity into polyketides. We selected the two unnatural SAM analogues propargylic Se-adenosyl-L-methionine (ProSeAM, 2)2d, 2h and keto-SAM (3)2d,13 for this study because both analogs can provide a reactive handle that can be further modified with mild, orthogonal chemistry. The selenium containing 2 was selected over the sulfur-based propargylic SAM derivative because it is more stable at physiological pH with a half-life of approximately one hour.2d

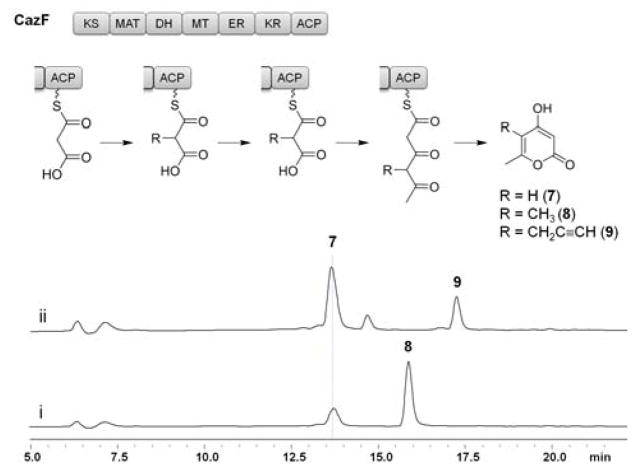

Figure 1.

α-pyrones 7–9 biosynthesized by CazF in the presence of (i) malonyl-CoA and SAM 1 or (ii) malonyl-CoA and ProSeAM 2. HPLC traces are shown in the same scale at λ= 280 nm. Domain organization of CazF consists of a ketosynthase (KS), malonyl-CoA:ACP acyltransferase (MAT), dehydratase (DH), methyltransferase (MT), enoyl reductase (ER) ketoreductase (KR) and acyl carrier protein (ACP).

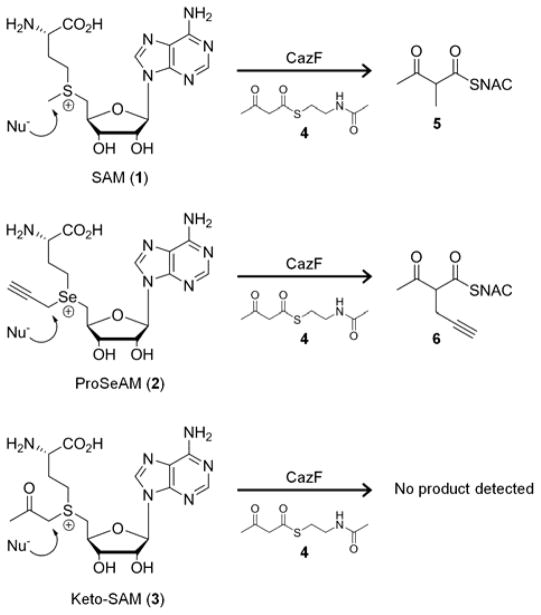

We first assayed the kinetics of the CazF MT domain towards the unnatural cofactors. Recombinant CazF was incubated with acetoacetyl-S-N-acetyl cysteamine (acetoacetyl-SNAC, 4) in the presence of 1, 2, or 3 (Scheme 1). The production of alkylated acetoacetyl-SNAC products were analyzed by liquid chromatography and mass spectroscopy (LC-MS); and kinetic constants were calculated by fitting initial velocity data at various concentrations of 1 or 2 to Michaelis-Menten parameters using nonlinear least squares curve fitting. In the assays containing 3, no product was detected suggesting that the MT domain would not accept the ketone derivative. The alkylated 5 and 6 were formed in the presence of 1 and 2, respectively. The steady-state kinetic parameters were kcat = 0.025 min−1 and KM = 15.5 μM for 1; and kcat = 0.036 min−1 and KM = 43.6 μM for 2. Although the turnover rates were slow for both 1 and 2, the comparable kinetic parameters indicate that the CazF MT displays similar preference towards 1 and 2. The slow turnover rate may be attributed to the use of a small molecule SNAC-bound substrate instead of an acyl-carrier protein (ACP)-tethered molecule.

Scheme 1.

CazF-mediated transalkylation of 4 using its natural cofactor 1 or unnatural analogues 2 or 3 as the alkyl donor

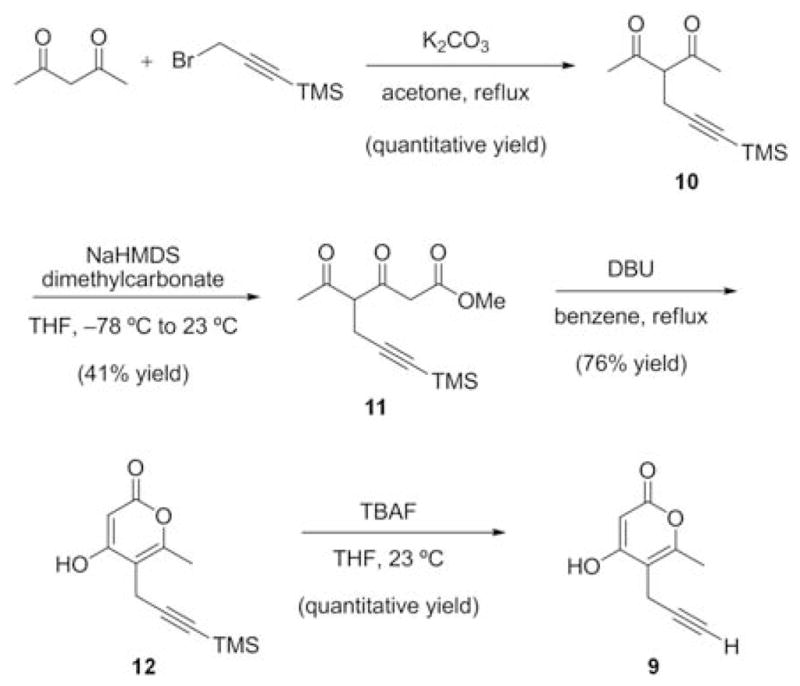

After confirming that the MT domain would accept 2 and transfer the propargyl moiety onto 4, we assessed whether the β-ketoacyl synthase (KS) domain of CazF would accept the propargylated-diketide intermediate and perform another decarboxylative Claisen condensation reaction with malonyl-CoA to form the propargylated triketide product. Previous in vitro characterization assays with CazF demonstrated that the enzyme can produce the triacetic acid lactone 7 when incubated with only malonyl-CoA, and the dimethylated α-pyrone 8 when SAM was included in the reaction (Figure 1).11 To determine whether CazF could produce a propargyl-α-lactone, the enzyme was incubated with malonyl-CoA and 0.2 mM of 2. Following incubation, the reaction mixture was treated with 1 M NaOH (base hydrolysis) and the organic extract was analyzed by LC-MS. Production of the propargylated-α-pyrone 9 was observed verifying that the KS domain can indeed tolerate the bulkier propargyl substituent in the diketide and extend it to the corresponding triketide product (Figure 1).14 To confirm the structure of 9 synthesized by CazF, a synthetic standard was prepared using a 4-step sequence (Scheme 2).15 Alkylation of commercially available 2,4-pentanedione with 3-bromoprop-1-yn-1-yl-trimethylsilane provided the dione 10, which in turn, was elaborated to the β,δ-diketoester 11 using sodium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide and dimethyl carbonate. A base-mediated cyclization of 11 with DBU yielded pyrone 12, which underwent alkyne deprotection to furnish 9.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 9 using 2,4-pentanedione and (3-bromoprop-1-yn-1-yl)trimethylsilane15

The higher amount of des-methylated compound 7 observed in the assay using 2 instead of 1 does suggest that under the reaction conditions, the rate of MT-alkylation is slower with the unnatural cofactor, and that the KS was able to outcompete the MT domain in extending the chain without alkylation. With the natural cofactor 1, MT-catalyzed methylation is faster, which results in 8 as the dominant product. Increasing the concentration of 2 to 1 mM did not alter the ratio of 9 and 7, which was expected since the KM towards 2 was measured to be <50 μM.

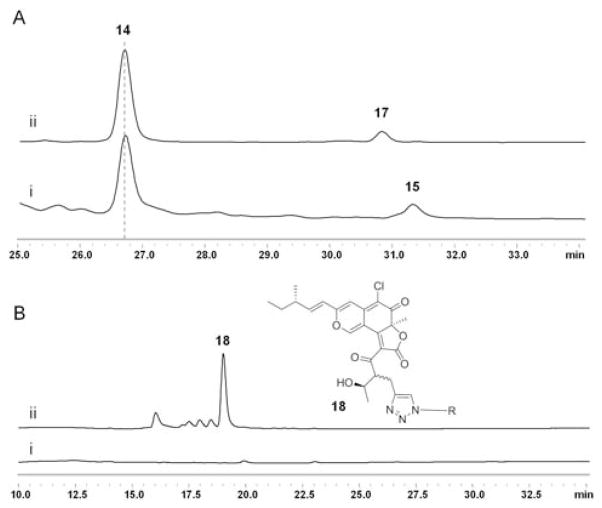

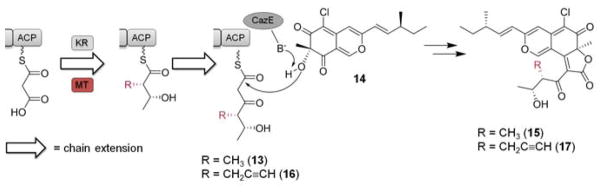

Previous in vitro reconstitution experiments established that when 1, along with NADPH used by the KR domain are present, the triketide product 13 is synthesized by CazF and is transacylated by the acyltransferase CazE to the pyranoquinone intermediate cazisochromene (14) to form chaetoviridin A (15) (Scheme 3).11 To further explore the tolerance of PKS domains, such as that of the KR towards the propargylated diketide and post-PKS accessory enzyme CazE towards the propargyl-containing polyketide intermediate 16, we tested whether an alkyne- containing analog of 15, such as 17, can be synthesized using the same set of enzymes. Equimolar amounts of CazF and CazE were incubated with 14, NADPH, malonyl-CoA and 2. LC-MS analysis of the organic extract revealed the formation of a new product with a shorter retention time than 15 and a [M+H]+ m/z = 457 (Figure 2A) consistent with that of 17. This new compound has an identical UV profile to 15 and an isotopic mass ratio consistent with the presence of one chlorine atom. Based on these observations, we assigned the product to be 4′ propargyl-chaetoviridin A (17). To provide additional evidence towards the identify of the new product, a Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne Huisgen cycloaddition reaction16 was performed to verify if 17 did indeed contain a terminal alkyne moiety. After reacting the organic extract containing 17 with azide-PEG3-5(6)- carboxytetramethylrhodamine, formation of a new peak 18 together with the disappearance of 17 was detected by LC-MS (Figure 2B). This new product exhibited UV absorption λmax at 550 nm, which is charcteristic of the rhodamine dye; and a [M+H]+ m/z = 1087, which is identical to the expected mass of the triazole-containing molecule 18 that forms as a result of alkyne mediated cycloaddition. Taken together, our experiments show that the propargyl functionality installed by the MT domain can indeed be propagated throughout the downstream reaction steps, and be found in the final natural product analog.

Scheme 3.

Biosynthesis of chaetoviridin A (15) and 4′-propargyl-chaetoviridin A (17) using the HR-PKS CazF, the acyltransferase CazE and the caz pyrano-quinone intermediate cazisochromene (14) in the presence of the alkylating cofactor 1 or 2.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the enzymatically synthesized chaetoviridins. A) HPLC analysis (360 nm) of chaetoviridins biosynthesized in vitro when (i) CazF and CazE were incubated with 14, malonyl-CoA, NADPH and 1 and (ii) CazF and CazE were incubated with 14, malonyl-CoA, NADPH and 2. B) HPLC analysis (550 nM) of the triazole-containing 18 after labeling 17 with the rhodamine-azide.

In summary, we demonstrated that the auxiliary MT domain within the highly-reducing fungal PKS CazF can act as a gateway for introducing orthogonally reactive functional groups into polyketides. Using the promiscuous nature of the MT domain, our study unveils an alternative approach for enhancing the structural diversity of natural products and opens the door for accessing and exploiting MT domains in other natural product systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.M.W. is supported by a L’Oréal USA Fellowship for Women In Science and G.C. is supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-0707424). This work is supported by the US National Institutes of Health (1DP1GM106413) to Y.T and (1DP2OD007335 and 1R01GM096056) to ML. These studies were supported by shared instrumentation grants from the NSF (CHE-1048804) and the National Center for Research Resources (S10RR025631).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures, enzymatic reactions, detailed synthetic reactions and NMR spectroscopic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Struck AW, Thompson ML, Wong L, Micklefield J. ChemBioChem. 2012;13:2642. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Peters W, Willnow S, Duisken M, Kleine H, Macherey T, Duncan KE, Litchfield DW, Lüscher B, Weinhold E. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:5170. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Islam K, Zheng W, Yu H, Deng H, Luo M. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:679. doi: 10.1021/cb2000567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang R, Zheng W, Yu H, Deng H, Luo M. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7648. doi: 10.1021/ja2006719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bothwell IR, Islam K, Chen Y, Zheng W, Blum G, Deng H, Luo M. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:14905. doi: 10.1021/ja304782r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Binda O, Boyce M, Rush JS, Palaniappan KK, Bertozzi CR, Gozani O. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:330. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wang R, Islam K, Liu Y, Zheng W, Tang H, Lailler N, Blum G, Deng H, Luo M. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:1048. doi: 10.1021/ja309412s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Blum G, Bothwell IR, Islam K, Luo M. Curr Prot Chem Biol. 2011;7:2970. doi: 10.1002/9780470559277.ch120241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Willnow S, Martin M, Luscher B, Weinhold E. ChemBioChem. 2012;13:1167. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Dalhoff C, Lukinavičius G, Klimašauskas S, Weinhold E. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:31. doi: 10.1038/nchembio754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dalhoff C, Lukinavičius G, Klimašauskkas S, Weinhold E. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1879. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Stecher H, Tengg M, Ueberbacher BJ, Remler P, Schwab H, Griengl H, Gruber-Khadjawi M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:9546. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang C, Weller RL, Thorson JS, Rajski SR. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2760. doi: 10.1021/ja056231t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansari MZ, Sharma J, Gokhale RS, Mohanty D. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:454. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Hagan D. The Polyketide Metabolites. Ellis Howard; Chichester, UK: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3468. doi: 10.1021/cr0503097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hertweck C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:4688. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Pickens LB, Tang Y, Chooi YH. Annu Rev Chem Biomol. 2011;2:211. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Winter JM, Tang Y. Curr Opin Biotech. 2012;5:736. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wilson MC, Moore BS. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:72. doi: 10.1039/c1np00082a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kennedy J. Nat Prod Rep. 2008;25:25. doi: 10.1039/b707678a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Sundermann U, Bravo-Rodriguez K, Klopries S, Kushnir S, Gomez H, Sanchez-Garcia E, Schulz F. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:443. doi: 10.1021/cb300505w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hughes AJ, Detelich JF, Keatinge-Clay AT. Med Chem Commun. 2012;3:956. [Google Scholar]; (c) Koryakina I, McArthur JB, Draelos MM, Williams GJ. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:4449. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40633d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koryakina I, McArthur J, Randall S, Draelos MM, Musiol EM, Muddiman DC, Weber T, Williams GJ. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:200. doi: 10.1021/cb3003489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winter JM, Sato M, Sugimoto S, Chiou G, Garg NK, Tang Y, Watanabe K. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:17900. doi: 10.1021/ja3090498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KK, Da Silva NA, Kealey JT. Anal Biochem. 2009;394:75. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee BWK, Sun HG, Zang T, Kim BJ, Alfaro JF, Zhou ZS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3642. doi: 10.1021/ja908995p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.In Figure 1 trace ii, there is a additional peak at 14.5 min. Based on its m/z, this compound is most likely propargylic Se-adenosyl.

- 15.For specific details on the synthetic reactions, please see the Supporting Information.

- 16.Huisgen R. In: 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry. Padwa A, editor. Wiley; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.