Abstract

Electrophoretic transport of proteins across electrochemically oxidized multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) membranes has been investigated. Small charged protein, lysozyme, was successfully pumped across MWCNT membranes by electric field while rejecting larger bovine serum albumin (BSA). Transport of the lysozome was reduced by a factor of about 30 in comparison to bulk mobility and consistent with prediction for hindered transport. Mobilities between 0.33-1.4×10-9 m2/V-s were observed and are approximately 10 fold faster than comparable ordered nanoporous membranes and are consistent with continuum models. For mixtures of BSA and lysozyme, complete rejection of BSA is seen with electrophoretic separations

1. Introduction

Nanoporous membranes have recently found increasing applications in therapeutic protein purifications,1, 2 membrane chromatography,3 biosensors4 and biomaterials.5 Much of the biotechnology revolution utilizes genetic modification of cells to express desired proteins for biomolecular treatments. However the separation of a specific protein from the large mixture of physiological proteins in a living system is a complex process. Membrane-based protein separations have the potential for single-step continuous operation that would result in low cost, high speed and high throughput processes.1-3, 6 Selectivity of proteins at a high flux is the primary limiting factor in membrane based processes. This is influenced by membrane physicochemical properties,7-9 and pore size and structure.10-12 For example, proteins could be excluded from an ultrathin membrane even with a maximum pore size more than twice as large as protein diameter,10 and protein diffusion coefficient in another nanoporous membrane was reported to be almost five orders lower than that in bulk solution.11 The trade-off between selectivity and speed is the primary challenge in biomolecular separations. To accelerate biomolecule transport across nanoporous membrane one can apply electric field (electrophoresis or electro-osmosis) or high pressure. In the case of applied pressure, membrane fouling is accelerated. Since proteins have different charge state, depending on the buffer pH, electric field induced transport of biomolecule in nano pores can offer selectivity and acceleration. Nanoporous gold and alumina membranes with high protein selectivity have been reported using electrophoresis and they offer promising new applications in bioseparations, biosensing and biomedical drug delivery.13-15 Inorganic nanoporous membranes, such as carbon and alumina membranes, also show greatly enhanced chemical, thermal and mechanical stability.16, 17 However due to the narrow pores and strong surface interactions, the fundamental issue of slow mobilities remains a challenge for the field. The ideal geometry would be nm-scale pores that match protein diameters, with ‘gate keeper’ chemistry to provide selectivity and followed by a pore with minimal interaction to allow high mobility.

Graphitic carbon nanotube (CNT) membranes are a new class of membranes18-26 which potentially have an ideal geometry for protein separations: a non-interacting graphite core and functional chemistry at the tips where carbon bonds are cleaved to open the membrane structure. The smooth graphitic cores allow dramatic enhancements in flow velocity of 10,000 fold compared to conventional pores19, 20 and gatekeeper activity has been demonstrated.21, 22 Recently, electro-osmosis and electrophoresis had been used to efficiently pump nicotine across CNT membranes for a programmable transdermal drug delivery device23 and can thus be applied to the translocation of proteins. However, a potential problem is if proteins have strong interactions with the hydrophobic CNT core thereby giving poor mobilities and little advantage compared to conventional materials. The interaction of proteins with CNT membranes has not been directly studied, however CNTs have been seen to have favorable physicochemical properties, showing promising applications in biological and biomedical engineering.27-33 An experimental study on DNA translocation through a single-walled CNT has been recently reported for DNA sequencing applications,34 thus suggesting the likely success of protein transport through CNTs. However for the use of CNT membranes in protein separations, it is critical to characterize the mechanisms of protein translocation through CNTs.

In this study, two typical model proteins of lysozyme (Lys) and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were selected to experimentally investigate the possibility of biomolecule transport through CNT membranes. These two proteins represent small and medium sized biomedical molecules respectively. Using electrochemically oxidized CNT membranes, single protein transport and two-protein separation were achieved using electrophoresis with the rejection of BSA by size exclusion.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

Model proteins, lysozyme from chicken egg white (L6876) and BSA (L7906), were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used as received without further purification. The hydrodynamic diameters of Lys (14.3 kD) and BSA (67 kD) are around 4.2 nm and 7.2 nm and the isoelectric points are 11.0 and 4.7, respectively. Tris (2, 2′-bipyridyl) ruthenium (Ru2+, Acros Organics) and methyl viologen (MV2+, Sigma Aldrich) were used as small permeate chemicals. Double-walled CNTs were purchased from Cheap Tubes and have a nominal inner diameter of 2 nm. Epon 862 epoxy resin (Miller Stephenson Chem.), Triton-X 100 (Sigma Aldrich) and hardener methylhexahydrophthalic anhydride (MHHPA, Broadview Tech.) were used for membrane fabrication.

4-sulfobenzene diazonium tetrafloroborate was synthesized using P-sulfonate anline and NaBF4 (Sigma Aldrich). Briefly, p-sulfonate anline was mixed with 50 ml DI water and 10 g 36% HCl. The solution was stirred at ice bath for 30 min. 4.20 g NaNO2 in 30 ml DI water at 0 °C was slowly added in previous solution for 2 hrs. 5.50 g NaBF4 was added in the solution. After 3 hours, the precipitation was filtered and washed by ice water.

2.2. Membrane Fabrication and Geometry

Multi-walled CNTs were fabricated via a chemical vapor deposition on quartz substrate using ferrocene/xylene as the source gas and have an average outer diameter of 40 nm and inner diameter of 7 nm.35 DWCNTs (2nm i.d.) powders were purchased from Cheap Tubes.com. CNT membranes were fabricated by the microtome method36 modified for high CNT loading.23 Briefly, 5wt.% CNTs were mixed with Epon 862 epoxy resin and Triton-X 100. MHHPA was used as hardener. A Thinky centrifugal sheer mixer was used to thoroughly mix the composite. After thermal curing in a vacuum oven at 80 °C, the composite was cut into 5 μm thick 6 mm diameter disks with conventional microtome using quartz blade. As diagramed in Figure 1, the MWCNT membranes were further treated with electrochemical oxidation37 to selectively etch CNTs into the polymer matrix leaving behind a polymer well with the outer diameter of CNT (∼40 nm).18 To electrochemically etch MWCNT membrane, 30 nm gold film was first sputtered on one membrane side for applying voltage. The etching was accomplished in a U-tube set-up, in which the membrane side to be etched faced 100 mM NaCl while another membrane side with gold film faced DI water. MWCNT membrane was utilized as working electrode and platinum counter and Ag/AgCl reference electrodes were installed in NaCl electrolyte. The etching bias was set to be 2.5 V. This shortens the length of MWCNTs and opens a significant fraction of CNTs blocked by iron catalyst to increase flux. After the electrochemical oxidization, the entrances of CNTs are expected to be modestly negatively charged with carboxylate groups. High negative charge density on CNT surfaces was obtained through chemical diazonium grafting using 4-sulfobenzene diazonium tetrafloroborate.22, 38 Pore area was measured by the flux of small molecule ionic diffusion and using Ficks law of diffusion with bulk diffusivities.19 Typical porosities are 0.01%.

Figure 1.

Schematic U-tube diffusion set-up and schematic of membrane with oxidized CNTs for biomolecular electrophoresis transport study.

2.3. Electrophoretic Transport of Protein

Electrophoretic transport of biomolecules through CNT membrane was carried out in a U-tube diffusion filter as shown Figure 1. Membrane area for permeation was 0.071 cm2. 1 ml (∼4.5 cm high) phosphate buffer (PB) with corresponding pH to protein feed solution was used as permeate solution and 5 ml feed protein solution was filled in other side and two sides was kept at the same height level. An e-DAQ e-corder 410 potentiostat was used with a three-electrode cell. Two platinum wires used as the counter and working electrodes were respectively set in the feed and permeate sides. Ag/AgCl electrode was used as the reference electrode. The feed concentration of each protein was 1 mg/ml in single or mixed protein solution. The net charge of protein was tuned by the pH value of 50 mM PB (the concentration ratio of the dibasic and monobasic salts).

2.4. Analysis of Protein

Bradford microassay (Brandford reagent for 1−1,400 μg/ml protein, B6916, Sigma Aldrich) was used to analyze the concentration of single protein or total proteins. Thermo Spectra HPLC system equipped with a size exclusion column (SEC) (Superose 12 10/300, 17-5173-01, GE Healthcare Bioscience) was used to qualitatively analyze proteins.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Electrophoretic Transport of Lysozyme

Figure 2 shows the typical SEM top-view images of a microtome cut membrane before and after electrochemical oxidation. For the as-cut CNT membrane, regions of short CNT tips stretching out of the embedding polymer were observed. After selectively electrochemical oxidizing a short length of the large outer diameter of MWCNTs (∼40nm o.d., 7nm i.d.), polymer wells on the oxidized side of the membrane were observed, consistent with prior reports.18

Figure 2.

Typical SEM top-view images of (a) microtome cut and (b) electrochemically oxidized MWCNT membranes.

The net charge of protein was tuned by the pH value of 50 mM PB. Table 1 shows the electrophoresis fluxes of lysozyme across the as-fabricated MWCNT membrane as a function of pH and bias. Representative analysis of the lysozyme in the permeate solution using SEC-HPLC is shown in Figure 3. Although ghost peaks were caused by elution buffer,39 the HPLC analysis showed that charged lysozyme was successfully pumped across MWCNT membrane by electric field while no significant pumping was observed for neutral protein (pH 11.0). The number of the unit net charge of lysozyme is +7 in pH 7.0 PB and +10 in pH 4.7 PB.40-42 However the electrophoresis of lysozyme increased 4 fold at pH 4.7, far larger than the charge increase, thus suggesting a possible change in protein conformation to significantly increase mobility. The effective hydrodynamic diameter of lysozyme was observed smallest at pH 4-6 and dynamic agglomeration of lysozyme was found at pH 8.1.43,44 For the DWCNT membranes, with 2 nm inner diameter, no electrophoretic lysozyme flux was observed. The hydrodynamic diameter of lysozyme is 4.2 nm, thus the DWCNT membrane was able to reject protein based on size exclusion.

Table 1.

Comparison of membrane area based diffusion and electrophoresis fluxes of lysozyme with different net charge across the electrochemically oxidized MWCNT membrane. Lysozyme feed: 1mg/ml. The isoelectric point of lysozyme is 11.0. D.L. signifies detection limit of 0.04 nmol/hr-cm2.

| Applied voltage | 0 V | -1 V | 0 V |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux of lysozyme in pH 4.7 PB, nmol/hr·cm2 | < D.L. | 1.6 | < D.L. |

| Flux of lysozyme in pH 7.0 PB, nmol/hr·cm2 | < D.L. | 0.36 | < D.L. |

| Flux of lysozyme in pH 11.0 PB, nmol/hr·cm2 | < D.L. | < D.L. | < D.L. |

Figure 3.

(a) SEC-HPLC chromatograms of the permeate solution collected at -1V and pH 7.0 electrophoresis for 24 hr and (b) 12.5 μg/ml (0.87 nmol/ml) lysozyme standard prepared in pH7.0 PB.

3.2. Electrophoretic Mobility of Lysozyme through CNT membranes

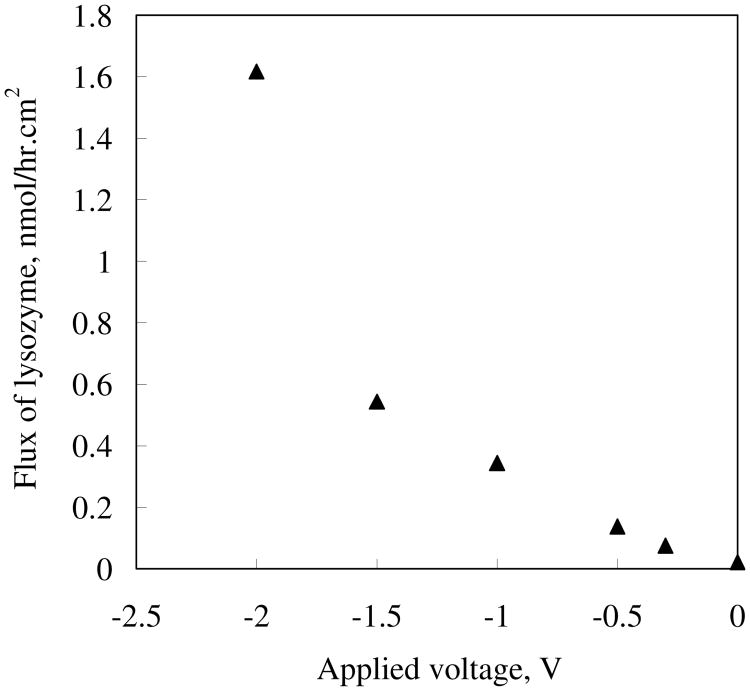

Applied voltage is the driving force for molecule transport by electrophoresis. The voltage dependence of the lysozyme flux is shown in Figure 4. A modest increase in slope by about a factor of two is seen between 0 and 1.5 V. At 2 V, a sharp increase in slope by nearly another factor of three is seen. To better analyze the data, the protein effective electrophoretic mobility (μ) and relative drag coefficient to bulk mobility (K) can be given as:

Figure 4.

Voltage dependence of the membrane area based electrophoresis flux of positively charged lysozyme dissolved in pH 7.0 PB.

| (1) |

Where C is the solute bulk concentration (different from concentration inner tubes), Jep is the electrophoresis flux based on pore area, vep is the solute electrophoresis velocity, μbulk is the bulk electrophoretic mobility, U is the applied voltage across the membrane and φ is the electric field gradient, l is the CNT length. This length is nominally the membrane thickness (5um) considering the short CNT length etched (∼20%) which is roughly equal to the longer path length of the randomly alignment of CNTs with respect to microtome cut.

Steady-state protein flux of charged molecule at electric field is given by45

| (2) |

Where D is the effective diffusion coefficient, F is the Faraday constant, R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, Jpore is the flux based on pore area, νeo is the electro-osmotic velocity, z is the number of unit charges of solute, dC/dx and dU/dx are the concentration and electric field gradient across membrane respectively.

Since the CNT channel and polymer chamber wall were not significantly charged and neutral lysozyme (pH 11.0) was not pumped with voltage, the electro-osmosis term, νeoC, can be neglected. Therefore, the increase protein flux with applied voltage can be understood by electrophoretic term (2nd term) in eqn. 2. Combining eqns. 1 and 2, the effective diffusion coefficient is given by the following Einstein relation between effective mobility and diffusion constant. Deff is an effective diffusion coefficient based on observed electrophoretic mobility. It is important to note that in small channels direct comparisons of this Deff to Brownian motion based diffusion is only a qualitative method to ascertain if there are large deviations from ideality.

| (3) |

The electrophoretic mobility of the charged lysozyme through the MWCNT membrane is shown in Table 2. The electrophoretic mobility in CNT membrane shows around 14-60 fold relative drag coefficient to bulk solution at applied voltage of 2 to 0.3 V. This indicates significant hindered electrophoresis for lysozyme in the CNT membrane pore (7nm i.d.), but is significantly improved over conventional nanoporous materials. The porosity of our oxidized MWCNT membrane was relative low (ca. 0.01%) and has low overall flux compared to more conventional membrane systems. However the electrophoretic mobility of lysozyme within the CNT membrane was increased compared to ordered nanoporous membranes with significantly larger 20 nm pore diameters.13 The applied voltages of 0.3 to 2 V were much lower than in porous alumina systems that required 6-35 V.13 This eliminates undesired bubble generation by water splitting and potentially damage to proteins from ionization during the electrical pumping. By increasing the porosity from the CNT membrane fabrication process one can realize significant performance advantages due to the modest protein interactions with CNT cores.

Table 2.

Electrophoretic mobility of positively charged lysozyme through electrochemically oxidized MWCNT membrane in pH 7.0 PB.

| Applied voltage | -0.3 V | -0.5 V | -1.0 V | -1.5 V | -2.0 V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrophoretic mobility, μ, m2/V·s | 3.3×10-10 | 4.2×10-10 | 5.8×10-10 | 6.3×10-10 | 14×10-10 |

| Relative drag coefficient, K | 61 | 48 | 34 | 32 | 14 |

| 44 (calculated with eqn.7 using 7 nm CNT diameter) | |||||

| Mobility reported, μ, m2/V·s | Bulk capillary eletrophoresis: 2.0×10-8 (pH=8.4)40 | ||||

| 20 nm gold nanotube membrane: 1.6×10-10 (pH=7.0, -6.0V)13 | |||||

Various models of hindered transport have been used to estimate the effective electrophoretic mobility and diffusion coefficient at different boundary conditions when the permeate molecule diameter approaches the pore diameter.21, 46-50 The reduced pore diameter (λ) is used and given by

| (4) |

Where dS is the permeate molecule diameter and dP is the pore diameter.

For electrophoresis at large Debye lengths, Zydney derived the following electrophoretic hindrance factor, Kd, for the electrophoreic mobility of a charged spherical particle at long Debye lengths in a spherical cavity, which we have used to predict the hindered electrophoretic mobility of lysozyme in the MWCNT membrane pores.50

| (5) |

Considering that we used solute bulk concentration to evaluate the electrophoretic mobility, the relative drag coefficient, K, should be given by:

| (6) |

Where φ is the partition coefficient that accounts for the use of bulk solution concentration.46

For simply steric interactions between the solute and the pore wall, the hindered diffusivity, Dh, can be estimated by Renkin's equation.21, 46

| (7) |

For 4.2 nm lysozyme within 7 nm CNTs, the predicted mobility is shown in Table 2. The predicted value of relative drag coefficient (44) was consistent with the experimentally observed ones (14-60). For the hindered diffusion coefficient predicted using eqn. 7 (Renkin's model), it is 2.0×10-12 m2/s, which shows the relative drag coefficient of around 55 compared to the bulk diffusion coefficient of 1.1×10-10 m2/s.40 The calculated effective diffusion coefficients using eqn. 3 are 1.2-5.2×10-12 m2/s. It is important to note that eqn. 7 does not include the electric field deformation around particles in narrow pores and is potentially a rough comparison but the effects should be minimized at large (non zero) Debye lengths. We also see a strong correlation of the observed mobility to the hindrance effect (hydrodynamic boundary effect) and thus justify excluding electric field deformation. This analysis also supports the conclusion that there were not prohibitively strong interactions of the small proteins with CNT walls that block CNT channels. For comparison to Brownian-diffusion based measurements11, diffusion coefficients are 3000 fold smaller and the use of electrophoresis dramatically reduces observed protein interactions within pores. This is also seen in our system where we could not detect lysosome transport above our detection limit in a diffusion experiment, but could with the application of electrophoretic bias.

Considering the complexity of protein structure and charge distribution,51 we felt it was important to compare the electrophoretic translocation of protein through the CNT channel to those of small molecules, Ru2+, MV2+. For the comparison of data, the electrophoresis enhancement, Eep is defined by the ratio of the electrophoretic flux (Jep) over the diffusive flux without voltage (J0) accounting for unit charge z. Eep is given by

| (8) |

Figure 5 shows that the proteins are significantly slower than small molecules when the voltage amplitude was less than 1 V. This can be explained by the lysozyme's comparable diameter to MWCNT inner diameter, leading to more hindered transport. Transport of the smaller molecules were not examined at high bias due to potential electrochemical reactions. However at an applied bias of -2 V for the protein, we see comparable enhancements (Eep) to small chemicals with extrapolated data to -2 V. Considering the flexible structure and the dynamic agglomeration of lysozyme,44 conformation change of proteins is possibly the reason for the faster translocation at -2 V. Conformation change of protein was observed in molecular dynamic simulation on the interactions between biomolecules and CNTs.30, 32 Other examples of voltage dependent mobility were also observed in DNA sequencing studies through nano structures.52

Figure 5.

Electrophoresis enhancement Eep, for lysozyme (diamond), Ru2+ (square) and MV2+ (triangle) at different applied voltage. Lysozyme and MV2+ were dissolved in pH 7.0 PB and Ru2+ was dissolved in DI water.

3.3. Bioseparation Using CNT membranes

To demonstrate the separation of proteins from mixtures we performed electrophoretic separations of 1 mg/ml lysozyne and 1 mg/ml BSA dissolved in 50 mM PB. For neutral (pH 4.7) or negatively charged BSA (pH > 4.7), no detectable BSA flux was found at -2 V applied voltage, but the total protein flux, measured by the more sensitive Bradford assay, was as high as 2.4 nmol/hr-cm2 in pH 7.0 and 5.9 nmol/hr-cm2 in pH 4.7. Figure 6 shows the typical SEC-HPLC analysis for the separation at pH 4.7 and -2 V applied voltage with no detectable BSA. This is compared to a dilute protein mixture calibration standard containing 2.5 μg/ml BSA and 2.5 μg/ml lysozyme. Considering the detection limit of our SEC-HPLC, the BSA concentration in permeate was negligible (less than 1 μg/ml) while total protein concentration from Bradford assay was as high as 55 μg/ml. Therefore a selectivity of >55 was achieved, however this selectivity value was set by the detection limit of the protein analysis. For the case of lysozyme and BSA being both positively charged in pH 3.0, no detectable BSA flux was found with lysozyme flux of 3.5 nmol/hr-cm2 though serious fouling was observed.

Figure 6.

Chromatograms of (left) permeate collected in the electrophoretic separation of charged lysozyme from neutral BSA in pH 4.7 PB at applied voltage of -2 V, and (right) standard mixture containing 2.5 μg/ml BSA and 2.5 μg/ml lysozyme to demonstrate detection limit of SEC-HPLC analysis.

Fouling is another difficult challenge facing membrane separations. In the case of the mixed lysozyme/BSA, the BSA is rejected by size exclusion and eventual fouling of the CNT pore is expected. Table 3 shows data of membrane fouling by after 12-48 hr separation runs. After the separation run, the unblocked pore area was measured by relative Ru2+ diffusional flux. For the positively charged lysozyme only studies, the membrane fouling was only about 20% after two days of diffusion. Such fouling is likely induced by the surface adsorption of protein, resulting in blockage of CNTs. It was interesting that no fouling was observed at the applied voltage of -2 V for lysozyme transport, indicating that the electric field applies enough force along the pore direction to prevent physisorption and fouling. In the case of mixed proteins the fouling was about 54% due to the dead end filtration of the large neutral BSA (pH 4.7). By changing the charge of BSA to be negative (pH 7.0), the electrophoretic force should repel the BSA and a 10% reduction in fouling was seen. We also attempted to use CNTs with high negative charge (diazonium grafting of benzosulfate) to repel anionic BSA, however similar fouling was seen. To recover the permeability of fouled CNT membrane, both washing with 0.2 M NaOH solution and further electrochemical oxidization (at the conditions that shortened CNT lengths) resulted in complete recovery. Taking advantage of the conductive CNTs to mitigate fouling by electrochemical oxidation is a promising approach for fouling resistance in membrane separations.

Table 3.

Fouling behavior of MWCNT membranes by protein mixtures. Feed concentration: 1 mg/ml. EP signifies electrophoresis.

| Experimental condition | Lysozyme only | Mixture of BSA and lysozyme | Membrane permeability recovery | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Diffusion, 48 hr | EP at -2 V | EP at -2 V and pH 7.0, 12 hr | EP at -2 V and pH 4.7, 12 hr | Washing with NaOH solution | Electrochemical oxidization | |

| Fouling extent (the reduction percent of Ru2+ flux) | 22% | No fouling | 43% | 54% | Total recovery | Total recovery |

4. Conclusions

Carbon nanotube membranes are a promising platform for complex protein or biomolecular separations. The transport of lysozyme through graphitic CNT cores was successfully induced by electric field pumping. Electrophoretic mobilities of lysozyme between 0.33-1.4×10-9 m2/V-s were observed and are approximately 10 fold faster than comparable porous gold nanotube membranes due to minimal interactions with CNT graphitic surface. Electrophoretic transport was through CNT cores was seen to be consistent with existing continuum models. For mixtures of BSA and lysozyme complete rejection of BSA was seen with electrophoretic separations. Eventual fouling by BSA was seen, however membrane permeability can be recovered by rinse with alkali solution or further electrochemical oxidization at the conductive CNT tips.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dali Qian and Rodney Andrews from the Center for Applied Energy, University of Kentucky, for supplying MWCNTs and Xin Zhan for the synthesis of 4-sulfobenzene diazonium tetrafloroborate. Facility support was provided by the Center for Nanoscale Science and Engineering and Electron Microscopy Center at the University of Kentucky. Financial support from NSF CAREER (0348544), DOE EPSCoR (DE-FG02-07ER46375) and NIH NIDA (R01DA018822).

References

- 1.Zydney AL. Biotech Bioeng. 2009;103:227–230. doi: 10.1002/bit.22308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, Ghosh R. Anal Chem. 2010;82:452–455. doi: 10.1021/ac902117f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh R. J Chromatogr A. 2002;952:13–27. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howorka S, Siwy Z. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:2360–2384. doi: 10.1039/b813796j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker LA, Jin P, Martin CR. Crit Rev Solid State Mat Sci. 2005;30:183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun XH, Yu DQ, Ghosh R. J Membr Sci. 2009;344:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang SL, Matsumoto H, Saito K, Minagawa M, Tanioka A. Biotech Prog. 2009;25:1379–1386. doi: 10.1002/btpr.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ku JR, Stroeve P. Langmuir. 2004;20:2030–2032. doi: 10.1021/la0357662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chun KY, Stroeve P. Langmuir. 2002;18:4653–4658. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Striemer CC, Gaborski TR, McGrath JL, Fauchet PM. Nature. 2007;445:749–753. doi: 10.1038/nature05532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma CB, Yeung ES. Anal Chem. 2010;82:478–482. doi: 10.1021/ac902487c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fissell WH, Dubnisheva A, Eldridge AN, Fleischman AJ, Zydney AL, Roy S. J Membr Sci. 2009;326:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2008.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu SF, Lee SB, Martin CR. Anal Chem. 2003;75:1239–1244. doi: 10.1021/ac020711a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osmanbeyoglu HU, Hur TB, Kim HK. J Membr Sci. 2009;343:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin CR, Kohli P. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:29–37. doi: 10.1038/nrd988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah TN, Foley HC, Zydney AL. J Membr Sci. 2007;295:40–49. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ismail AF, David LIB. J Membr Sci. 2001;193:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinds BJ, Chopra N, Rantell T, Andrews R, Gavalas V, Bachas LG. Science. 2004;303:62–65. doi: 10.1126/science.1092048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majumder M, Chopra N, Andrews R, Hinds BJ. Nature. 2005;438:44–44. doi: 10.1038/43844a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holt JK, Park HG, Wang YM, Stadermann M, Artyukhin AB, Grigoropoulos CP, Noy A, Bakajin O. Science. 2006;312:1034–1037. doi: 10.1126/science.1126298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Majumder M, Chopra N, Hinds BJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9062–9070. doi: 10.1021/ja043013b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Majumder M, Zhan X, Andrews R, Hinds BJ. Langmuir. 2007;23:8624–8631. doi: 10.1021/la700686k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu J, Paudel KS, Strasinger C, Hammell D, Stinchcomb AL, Hinds BJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11698–11702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004714107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mi WL, Lin YS, Li YD. J Membr Sci. 2007;304:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu M, Funke HH, Falconer JL, Noble RD. Nano Lett. 2009;9:225–229. doi: 10.1021/nl802816h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim S, Jinschek JR, Chen H, Sholl DS, Marand E. Nano Lett. 2007;7:2806–2811. doi: 10.1021/nl071414u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang WR, Thordarson P, Gooding JJ, Ringer SP, Braet F. Nanotechnology. 2007;18:412001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu B, Li XY, Li BL, Xu BQ, Zhao YL. Nano Lett. 2009;9:1386–1394. doi: 10.1021/nl8030339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller SA, Young VY, Martin CR. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:12335–12342. doi: 10.1021/ja011926p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie YH, Kong Y, Soh AK, Gao HJ. J Chem Phys. 2007;127:225101. doi: 10.1063/1.2799989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nepal D, Geckeler KE. Small. 2007;3:1259–1265. doi: 10.1002/smll.200600511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang Y, Liu YC, Wang Q, Shen JW, Wu T, Guan WJ. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2807–2815. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nednoor P, Gavalas VG, Chopra N, Hinds BJ, Bachas LG. J Mater Chem. 2007;17:1755–1757. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu HT, He J, Tang JY, Liu H, Pang P, Cao D, Krstic P, Joseph S, Lindsay S, Nuckolls C. Science. 2010;327:64–67. doi: 10.1126/science.1181799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrews R, Jacques D, Rao AM, Derbyshire F, Qian D, Fan X, Dickey EC, Chen J. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;303:467–474. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun L, Crooks RM. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:12340–12345. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ito T, Sun L, Crooks RM. Electrochem Solid State Lett. 2003;6:C4–C7. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stewart MP, Maya F, Kosynkin DV, Dirk SM, Stapleton JJ, McGuiness CL, Allara DL, Tour JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:370–378. doi: 10.1021/ja0383120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams S. J Chromatogr A. 2004;1052:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.07.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szymanski J, Pobozy E, Trojanowicz M, Wilk A, Garstecki P, Holyst R. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:5503–5510. doi: 10.1021/jp067511d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuehner DE, Engmann J, Fergg F, Wernick M, Blanch HW, Prausnitz JM. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:1368–1374. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bostrom M, Williams DRM, Ninham BW. Biophys J. 2003;85:686–694. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74512-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonincontro A, De Francesco A, Onori G. Colloid Surf B-Biointerfaces. 1998;12:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ho AK, Perera JM, Dunstan DE, Stevens GW, Nystrom M. AIChE J. 1999;45:1434–1450. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srinivasan V, Higuchi WI. Int J Pharm. 1990;60:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deen WM. AIChE J. 1987;33:1409–1425. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shugai AA, Carnie SL. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1999;213:298–315. doi: 10.1006/jcis.1999.6143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keh HJ, Chiou JY. AIChE J. 1996;42:1397–1406. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keh HJ, Anderson JL. J Fluid Mech. 1985;153:417–439. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zydney AL. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1995;169:476–485. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Firnkes M, Pedone D, Knezevic J, Doblinger M, Rant U. Nano Lett. 2010;10:2162–2167. doi: 10.1021/nl100861c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu JP, Mao P, Han J. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]