Abstract

Macrophages serve as vehicles for the carriage and delivery of polymer-coated nanoformulated antiretroviral therapy (nanoART). Although superior to native drug, high drug concentrations are required for viral inhibition. Herein, folate-modified atazanavir/ritonavir (ATV/r)-encased polymers facilitated macrophage receptor targeting for optimizing drug dosing. Folate coating of nanoART ATV/r significantly enhanced cell uptake, retention and antiretroviral activities without altering cell viability. Enhanced retentions of folate-coated nanoART within recycling endosomes provided a stable subcellular drug depot. Importantly, five-fold enhanced plasma and tissue drug levels followed folate-coated formulation injection in mice. Folate polymer encased ATV/r improves nanoART pharmacokinetics bringing the technology one step closer to human use.

Keywords: human immunodeficiency virus, nanoART, ATV/r, targeted drug delivery, folate, poloxamer 407, macrophages

Introduction

Requirements for lifelong daily antiretroviral dosing, secondary toxicities and poor penetrance into lymphoid and central nervous system (CNS) viral reservoirs limit long-term clinical outcomes for human immunodeficiency virus type one (HIV-1) disease.1,2 Indeed, even under the most optimal of circumstances, antiretroviral therapy (ART) compliance remains a substantive clinical concern.3,4 Furthermore, cessation of ART is associated with a rapid viral rebound and accelerated HIV-1 resistance.5 Thus, optimal ART regimens require maintenance of plasma drug levels, limited toxicities and penetrance of drug into viral reservoirs. All remain elusive.6,7 Therefore, the development of long acting cell targeted ART is of immediate importance. This is especially notable as infected patients live well into their sixth and seventh decades of life. The approach our laboratory has taken to meet the goals of a clinically applicable long acting ART rests in the development of crystalline-coated ART coated with cell receptor targeted polymers.8–10 We reasoned that such nanoformulated ART (nanoART) could target macrophages serving as drug transporters. Indeed, the use of highly mobile monocytes and macrophages make biological sense as the cells have large storage capacities and can enter sites of infection, injury and inflammation.11 These include lymph nodes and the central nervous system (CNS).12–14 Such a “Trojan Horse Carriage” offers several advantages from native drugs for targeted drug delivery, achievement of therapeutic concentrations in reservoirs of infection, prolonged drug half-lives and enhanced efficacy, pharmacokinetics and drug biodistribution. All was realized in our prior studies in cell and animal models of viral infections.8–10,15–18 NanoART storage is in macrophage recycling endosomes.19 We reasoned that further improvements could be realized by adding a targeted ligand in order to facilitate nanoparticle uptake in cells. One means to facilitate such an improved particle uptake was by coating the polymer with folic acid (FA). The folate receptor (FOLR) is expressed on macrophages and can facilitate drug uptake in cancer models.20–24

We theorized that while the importance of targeted nanoART cannot be overstated improvements could be seen to facilitate drug tissue delivery, reduce ART dosing and facilitate lymphoid and CNS drug penetrance.15,18 To this end, we developed a scheme for macrophage targeting. One possibility was through FA. Indeed, previous studies by others have shown a functional FOLR on macrophages.24 As activated macrophages express FOLR2 we reasoned that FA attachment to nanoART could facilitate particle uptake and cell retention. NanoART enters macrophages and resides in intracellular compartments where it retains robust antiretroviral activities.19 Chemical attachment of FA residues to the polymer coating of antiretroviral nanoparticles was achievable and subsequent purification served to enhance drug concentrations inside cells. All together, the pharmacokinetic parameters of FA coated nanoART showed improved cell drug delivery. The implications of these findings to the clinic are noteworthy.

Methods

Chemicals

Atazanavir (ATV) sulfate was purchased from Longshem Co (Shanghai, China) and free-based with triethylamine. Ritonavir (RTV) was purchased from Shengda Pharmaceutical Co (Zhejiang, China). Poloxamer 407 (P407), folic acid (FA), and CF633-succinimidyl ester (CF633) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and N-hydroxysuccinimide, N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide and triethylamine from Acros Organics (Morris Plains, NJ, USA). Sephadex LH-20 was obtained from GE HealthCare (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Human serum and macrophage colony stimulating factor (MCSF) were generous gifts of Pfizer Inc. (Cambridge, MA, USA).

Human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM)

Human peripheral blood monocytes were obtained by leukapheresis from HIV-1 and hepatitis seronegative donors and purified by counter-current centrifugal elutriation.11 The cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% heat-inactivated pooled human serum, 1% glutamine, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, 10 μg/ml ciprofloxacin and 1000 U/ml MCSF.25

Preparation of targeted and non-targeted nanoART

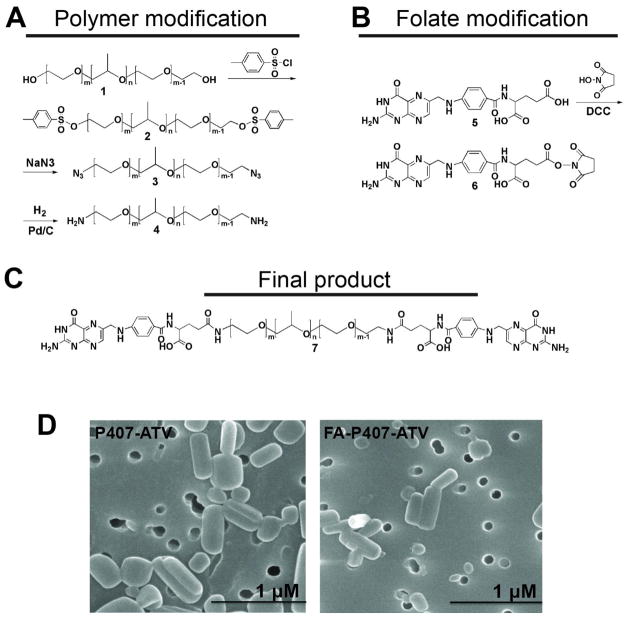

Synthesis of folate-modified poloxamer 407 is described in the supplementary methods and in Figure 1A–C. FA-P407-ATV was prepared using a mixture of 40% FA-P407, 60% P407, and free-base ATV by high-pressure homogenization as previously described.8,26

Figure 1. Synthesis of folate conjugated poloxamer 407 (FA-P407).

Schematic representation of the modifications for (A) poloxamer 407 and (B) folate and subsequent reaction to yield (C) FA-P407. (D) Scanning electron micrographs of FA-P407-ATV and P407-ATV.

Preparation of CF633 labeled nanoART

For preparation of CF633-labeled FA-P407-ATV, CF633-P407, FA-P407 and P407 were dissolved together in methanol at a weight ratio of 2:2:1. The solvent was evaporated using a Rotavap to form a thin polymer film. The polymer film was rehydrated with 10mM HEPES to prepare 0.5% polymer solution. ATV free-base (150 mg) was added to this polymer solution, and the suspension was mixed overnight at room temperature, protected from light. The suspension was homogenized by a high-pressure system.8,26 For preparation of CF633-labeled P407-ATV, CF633-P407 and P407 were dissolved in methanol at a weight ratio of 2:3.

Purification and quantification of FA-P407-ATV

The crude nanosuspension was purified by a series of centrifugation steps. FA-P407-ATV nanosuspension was centrifuged at 5,000 and 1,000 × g for 5 then 10 minutes. Supernatant was collected and again centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 minutes to separate nanoART from micelles and free drug. The nanoART pellet was suspended in 0.5% P407 and used immediately for cell culture studies. UV/Vis spectrometry, 1H-NMR, and HPLC were used to determine the amount of FA in the nanoformulation and the drug to polymer ratio in the nanoART pellet and supernatant. The amount of FA in the formulation was determined by the absorbance at 355 nm and compared against a FA standard curve. Each formulation was dissolved in DMSO and sonicated for 5 minutes. Drug content in the purified nanosuspension was determined by HPLC.8,17

Physicochemical characterization of nanoART

Particle size, polydispersity index (PDI) and zeta potential were measured by dynamic light scattering using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano Series Nano-ZS (Malvern Instruments Inc, Westborough, MA, USA). Particle shape was determined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a Hitachi S4700 field-emission scanning electron microscope (Hitachi High Technologies America Inc, Schaumburg, IL, USA).8,17 Atomic force microscopy (data not shown) and 1H-NMR were used to characterize the nanoART particles.

Folate receptor expression

Expression of FOLR by MDM was determined by Western blot and confocal microscopy. For Western blots, MDM were collected at day 7 and lysed using cell lysis buffer (Cell Lytic™ M (C2978); Sigma Aldrich) with 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cell lysates were prepared from A2780 cells (FOLR1 positive), chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (folate receptor negative), and CHO cells transfected with human FOLR2 (CHO-hFRβ, a generous gift from Dr. Philip Low, Purdue University 27). Protein content of cell lysates was determined using a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cell lysate protein (20 μg) was separated on a NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 100 volts for 2 hours then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane at 30 volts for 1.5 hours. The membrane was blocked with 5% powdered milk and probed with antibodies against human FOLR1 (1:200; AF5646; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or human FOLR2 (1:200; AF5697; R&D Systems) overnight followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA). The membrane was visualized using a Pierce SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) and developed on X-ray film. For confocal microscopy, monocytes were cultured on 8 well Lab-Tek II CC2 chamber slides at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells/well for 7 days. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 minutes, permeabilized and blocked with 0.1% Triton/5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl for 15 minutes. The cells were then washed with 0.1% Triton and incubated with FOLR2 antibody (1:50; AP5032a; Abgent, San Diego, CA, USA) for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by the addition of secondary antibody conjugated with AlexaFluor 488 (Life Technologies) for 45 minutes at 37°C. ProLong Gold anti-fade reagent with DAPI (Life Technologies) was added and slides were cover slipped and imaged with an LSM 510 microscope using a 63X oil lens (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc., NY, USA).

MDM uptake, retention and release

Cell uptake, retention and release were determined as previously described.8,17 Briefly, MDM were treated with 100 μM FA-P407-ATV or P407-ATV for 8 hours. Cells were collected by scraping into PBS and pelleted by centrifugation at 950 × g for 8 minutes. The cell pellets were sonicated in 200 μl methanol, centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 minutes, and drug concentrations determined.8,17 For retention and release studies MDM were treated with 100 μM FA-P407-ATV or P407-ATV for 8 hours; cells were washed with PBS and fresh drug, and MCSF-free medium was added. MDM and medium were collected on days 1, 5, 10 and 15, and drug content was determined by HPLC.8,17 For FA inhibition studies, MDM were pre-incubated with FA at concentrations of 0, 1.5, 3.1, 12.5 and 50 mM for 45 minutes. The cells were then treated with 100 μM FA-P407-ATV for 8 hours and lysed. The amount of drug taken up by the cells was determined by HPLC. 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay for cell viability was performed as previously described.10 Briefly, MDM were treated with 10, 50, 100 and 200 μM nanoART for 24 hours. The cells were washed with PBS. MTT solution (5 mg/ml) was added and the plate was incubated for 45 minutes then washed with PBS. DMSO was added to cells, incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature then read on a UV-VIS spectrophotometer at 490 nm.

Measurements of antiretroviral activity

MDM were treated with nanoART for 8 hours and then challenged with HIV-1ADA at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01 infectious viral particles/cell 25 on days 1, 5, 10 or 15 after nanoART treatment. Following viral infection, cells were cultured for 10 days with half media exchanges every other day. Infected culture supernatant fluids were assayed for reverse transcriptase (RT) activity and cell HIV-1p24 protein expresssion assessed by immunostaining.8,17, 28

Subcellular localization by confocal microscopy

For confocal imaging, monocytes were cultured on an 8 well Lab-Tek II CC2 chamber slide at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells per well in the presence of 10% human serum and MCSF for 7 days. The cells were treated with 100 μM of either CF633 labeled FA-P407-ATV or CF633 labeled P407-ATV for 8 hours at 37°C, washed, fixed and stained with antibodies as described by Kadiu et al.19 Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 30 minutes, permeabilized, and blocked with 0.1% Triton and 5% BSA in PBS and then quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl for 15 minutes. The cells were then washed with 0.1% Triton and incubated with primary antibodies (1:50) against endocytic compartments, RAB7 (late endosomes), RAB11 and RAB14 (recycling endosomes) and LAMP1 (lysosomes) (Rab 7 (SC-10767), Rab11 (SC-6565) and Rab 14 (SC-98610) antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; and LAMP1 antibody ((NB120-19294) from Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) for 1 hour at 37°C. Following incubation with primary antibody, the cells were washed and incubated with corresponding secondary antibody conjugated with AlexaFluor 488 for 45 minutes at 37°C. ProLong Gold anti-fade reagent with DAPI was added and slides were cover slipped and imaged with an LSM 510 microscope using a 63X oil lens.

Pharmacokinetic studies

The protocols for animal experiments and cell elutriation were in accordance with University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the Institutional Review Board. All animal studies were conducted humanely, and human cells were collected with informed consent. Male Balb/cJ mice (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were maintained on a folate-deficient diet (Harlan Teklad TD.00434; Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, USA) beginning 2 weeks prior to nanoART administration. Mice were injected with FA-P407-ATV/RTV (ATV/r) or P407-ATV/RTV (50 or 100 mg/kg each drug) intramuscularly (IM). Plasma was collected 1, 3, 5, 7, 10 and 14 days after nanoART administration. Tissues (liver, kidney, brain, spleen, lymph node and muscle) were collected after sacrifice on day 14. ATV and RTV from plasma and tissues were extracted using acetonitrile and assayed by UPLC-MS/MS as previously described.29

Statistical analysis

Immunofluorescence was quantitated using ImageJ software, JACoP plugin for percent overlap and Zeiss LSM 510 Image browser AIM software version 4.2 for determining the number of pixels and mean intensity of each channel.30 For each sample, images were taken in quadruplicate, and 40 cells per treatment were analyzed. The ratio of total red intensity in the co-localized area versus the total intensity of green in the region of interest was calculated. Percent overlap represents the percentage of nanoART overlapping with the cell compartment.30 Statistical analysis was performed by 2-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA, USA). Results are represented as mean ± SEM (standard error of mean). Results are significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Physicochemical parameters of nanoART and FOLR expression on MDM

The physicochemical characteristics of P407-ATV and FA-P407-ATV were nearly equivalent. The size, polydispersity index and zeta potential for P407-ATV nanoparticles were 385 ± 10 nm, 0.23 ± 0.1 and −18.5 ± 2.2 mV respectively. Alternatively, the size, polydispersity and zeta potentials for FA-P407-ATV were 362 ± 14 nm, 0.27 ± 0.04 and −19.7 ± 4.7 mV respectively. Figure 1D shows SEM images for the ATV/r nanoART. Rod-like particles were observed in both formulated nanosuspensions.

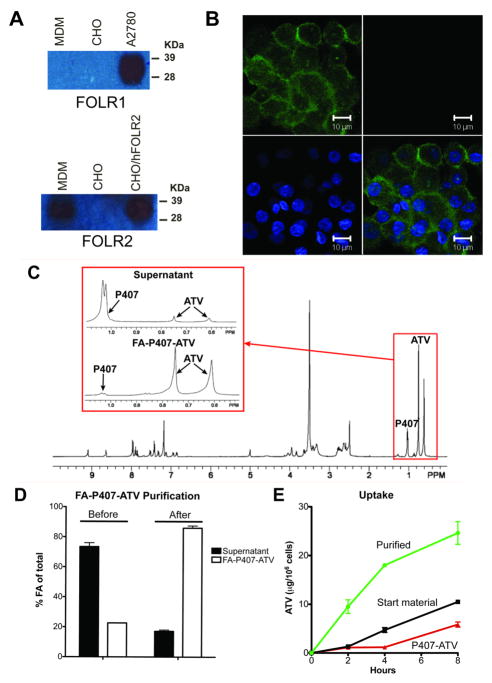

Expression of FOLR2 (FRβ) in activated macrophages was reported by several groups.24,27,31,32 To confirm such FOLR MDM expression, cell lysates were probed with antibodies to both FOLR1 and FOLR2. As seen in Figure 2A, MDMs expressed FOLR2, but not FOLR1. Expression of FOLR2 (green) was localized on the cell membrane by confocal microscopy (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Characterization of folate receptor (FOLR) on MDM.

(A) Western blot for FOLR1 and FOLR2. (B) Confocal image demonstrating FOLR2 expression on MDMs. FOLR2 (green) and nuclei (blue). Scale bar = 10 μm. Characterization of purified FA-P407-ATV. (C) 1H NMR spectra of nanosuspension before purification (inserts show peaks for P407 and ATV in supernatant and FA-P407-ATV pellet after purification) (D) Folic acid quantification in the supernatant and FA-P407-ATV pellet before and after purification. (E) MDM uptake of purified FA-P407-ATV compared to unpurified starting material and non-targeted P407-ATV. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3.

Purification of nanosuspensions

In addition to polymer-coated drug crystals, crude nanosuspensions produced by high-pressure homogenization had free polymer and polymer micelles with low drug loading. Thus, FA-P407 polymer and FA-P407 micelles could compete for FOLR binding with FA-P407-ATV and reduce drug uptake. To remove excess FA-P407 and polymer micelles, the crude nanosuspension was purified by differential centrifugation. The process removed excess free FA-P407 polymer and micelles. 1H-NMR analysis of the crude nanosuspension along with the purified FA-P407-ATV (pellet) and supernatant after centrifugation showed (Figure 2C) that most of the drug was associated with the purified FA-P407-ATV pellet indicating that the centrifugation steps did not result in a significant loss of ATV from the nanoparticles. In order to determine the efficiency of purification, FA levels in the nanosuspension, before and after purification, were determined by UV-Vis spectrophotometry. The percent of FA present in the FA-P407-ATV fraction as a function of total FA in the nanosuspension was increased from 20% before purification to 80% after purification (Figure 2D). Purification enhanced MDM uptake of FA-P407-ATV by at least 2-fold compared to the non-purified starting material (24.6 ± 1.3 and 10.5 ± 0.2 μg ATV/106 cells, respectively) (Figure 2E).

Targeted nanoART uptake and retention in MDM

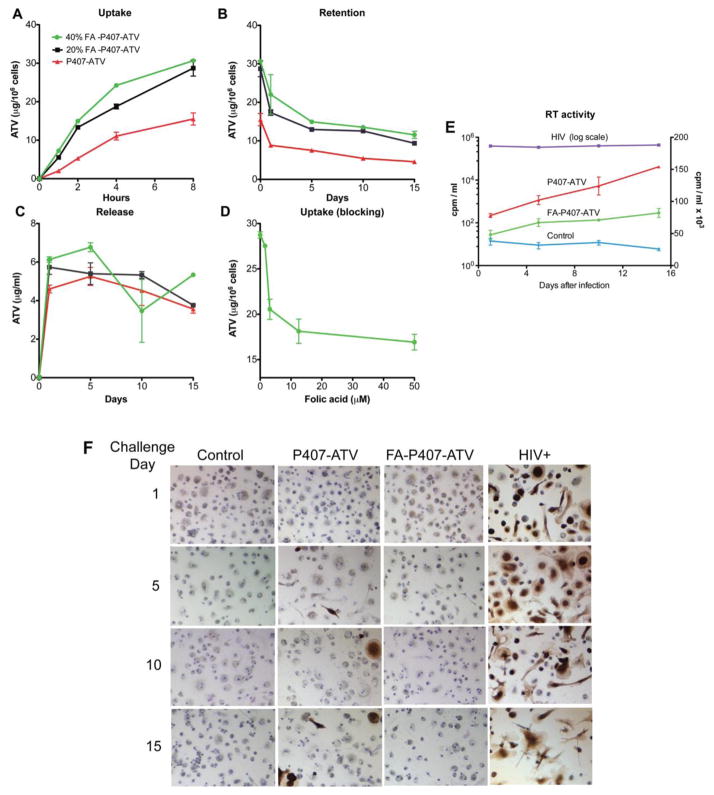

To determine whether FOLR targeting would enhance nanoART uptake, MDM were treated with 100 μM FA-P407-ATV or P407-ATV. As shown in Figure 3A, nanoART coated with 20% or 40% FA-P407 were taken up 2-fold greater by MDMs than non-targeted (0% FA-P407) nanoART (28.7 ± 1.2, 30.6 ± 0.3, and 15.5 ± 0.9 μg ATV/106 cells, respectively). A greater amount of drug (9–12 μg ATV/106 cells) was retained in the cells over 15 days with 20% and 40% FA-P407-ATV treatment than with non-targeted P407-ATV (4.5 μg ATV/106 cells), reflecting the initial increased cell loading (Figure 3B). The nanoformulations exhibited similar release profiles of approximately 5 μg ATV/ml over 15 days (Figure 3C). To determine whether this enhanced uptake was mediated by the FOLR, free folate was added to MDM prior to treatment with FA-P407-ATV to block receptor binding. As shown in Figure 3D, uptake of FA-P407-ATV by MDMs was inhibited by increasing concentrations of free FA to levels observed for P407-ATV. Treatment with targeted and non-targeted nanoformulations with up to 100 μM ATV did not result in cell toxicity as determined by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay (data not shown).

Figure 3. Uptake, retention, release and antiretroviral efficacy of FA-P407-ATV in MDM.

(A) Time course for MDM uptake of ATV nanoformualtions. Macrophages were administered with 100 μM FA-P407-ATV containing either 0%, 20%, or 40% FA-P407 for 8 hours. Timecourse of (B) MDM retention and (C) release of nanoART into medium over 15 days following an 8 hour loading with 100 μM nanoART. (D) Inhibition of MDM uptake of 100 μM FA-P407-ATV by pre-incubation with 1.5–50 mM free FA for 45 minutes. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3. (E) Antiretroviral efficacy of FA-P407-ATV in MDM infected with HIV-1ADA for 1, 5, 10 and 15 days after drug treatment. Level of infection was determined by RT activity in culture supernatant fluids. The left logarithmic y-axis shows RT levels of HIV-1 infected cells without drug. The right linear y-axis shows data for control (uninfected), FA-P407-ATV and P407-ATV treated cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3. Statistical differences were determined using Student’s t-test; *P < 0.05 considered significant. (F) HIV-1 p24 (brown) staining for MDM challenged with HIV-1ADA at 1, 5, 10 and 15 days after FA-P407-ATV treatment. Images are representations of 3 identically treated wells.

Antiretroviral efficacy of targeted nanoART

To determine whether the increased nanoART loading and retention observed for targeted nanoART would translate to improved antiretroviral efficacy, MDMs were treated with 100 μM FA-P407-ATV or P407-ATV for 8 hours and then challenged with HIV-1ADA at 1, 5, 10 and 15 days later. FA-P407-ATV exhibited better antiretroviral activity than P407-ATV as determined by RT activity and p24 staining (Figure 3E,F). HIV-1 replication was reduced by 81% (82 cpm/ml × 103) with FA-P407-ATV as compared to 64% (154 cpm/ml × 103) for P407-ATV on challenge day 15. Similar results were obtained at challenge days 1, 5, and 10 where FA-P407-ATV suppressed viral replication by 87% (48 cpm/ml × 103), 80% (67 × cpm/ml × 103) and 82% (71 CPM/ml × 103) whereas P407-ATV suppressed viral replication by 80% (78 cpm/ml × 103), 70% (102 cpm/ml × 103) and 68% (124 cpm/ml × 103) at days 1, 5 and 10 respectively (Figure 3E). Suppression of viral replication by FA-P407-ATV was significantly greater compared to P407-ATV at days 1, 5 and 15 (Student’s t-test, P < 0.01). These results were verified by HIV-1 p24 antigen expression (Figure 3F). MDMs treated with P407-ATV showed increased viral infection over time (as evidenced by brown staining) whereas little to no p24 antigen was detected in MDMs treated with FA-P407-ATV.

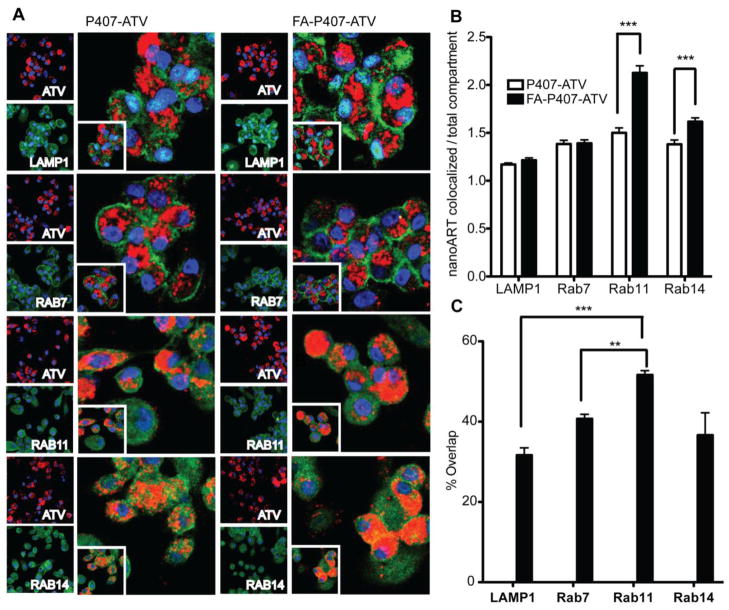

Subcellular localization of FA-P407-ATV and P407-ATV nanosuspensions

To determine the sub-cellular localization of the nanoART taken up by the macrophages, MDM were treated with CF633-labeled FA-P407-ATV or P407-ATV. Particle size, PDI, and zeta potential for CF633-P407-ATV (376 ± 2 nm, 0.25 ± 0.1 and −5 ± 0.3 mV, respectively) and for CF633-FA-P407-ATV (351 ± 4 nm, 0.27 ± 0.1 and −10 ± 0.6 mV, respectively) were similar to that for the unlabeled nanoART. After 8 hours, the cells were fixed with 4% PFA, and endosomal compartments were stained using specific antibodies. Co-localization of the particles with endosomal compartments was determined by confocal imaging. LAMP1 antibody identified the lysosomal compartments, Rab7 antibody identified the compartments involved in late endosomal sorting and Rab11 and Rab14 antibodies identified recycling endosomal compartments (Figure 4A). The ratio of intensity of nanoART in the colocalized region versus the intensity of endosomal compartments was used to determine how well the nanoART was taken up by each cell compartment. These intensity values were determined using Zeiss LSM 510 Image browser version 4.2. As shown in Figure 4A Rab11 recycling endosomes took up the FA-P407-ATV approximately 1.5-fold greater than P407-ATV (P < 0.001, n = 40). Furthermore, the FA-P407-ATV localized to a greater extent in the Rab14 recycling endosomes (P < 0.001, n = 40) than P407-ATV. There were no significant differences between the amount of FA-P407-ATV and P407-ATV particles localized within LAMP1 and Rab7 compartments (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Subcellular localization of FA-P407-ATV and P407-ATV.

MDM were cultured for 7 days on LabTek CC2 chamber slides and treated with 100 μM CF633-labeled P407-ATV or FA-P407-ATV for 8 hours. (A) The cells were stained with LAMP1, Rab7, Rab11, or Rab14 primary antibodies and AlexaFluor 488-labeled secondary antibodies to visualize the corresponding cell compartments using confocal microscopy. Nanoparticles are shown in red, cell compartments in green, and nuclei in blue. Quantitation of subcellular compartment co-localization of FA-P407-ATV and P407-ATV. (B) Ratio of nanoART co-localized with cell compartments (intensity) to total intensity of the compartment in the cell (n=40) was determined by Zeiss LSM 510 Image browser version 4.2. (C) Overlap coefficients for each of the cell compartments with CF633-FA-P407-ATV. Statistical analysis was performed by 2 way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison; *P < 0.05 considered significant (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Quantification of percent overlap between nanoART and cell compartments measured by overlap coefficient (ImageJ, JACOP plugin) showed significantly greater co-localization with Rab 11 recycling endosomal compartments, 52 ± 1% (P < 0.0001), than with lysosomes (LAMP1; 31 ± 2%) (Figure 4C). Distribution into late endosomal compartments, as indicated by Rab7 co-localization (40%), was greater than lysosomes, but significantly less than in Rab11 recycling endosomes. NanoART distribution among the cell compartments was similar for FA-P407-ATV and P407-ATV (data not shown).

Pharmacokinetics

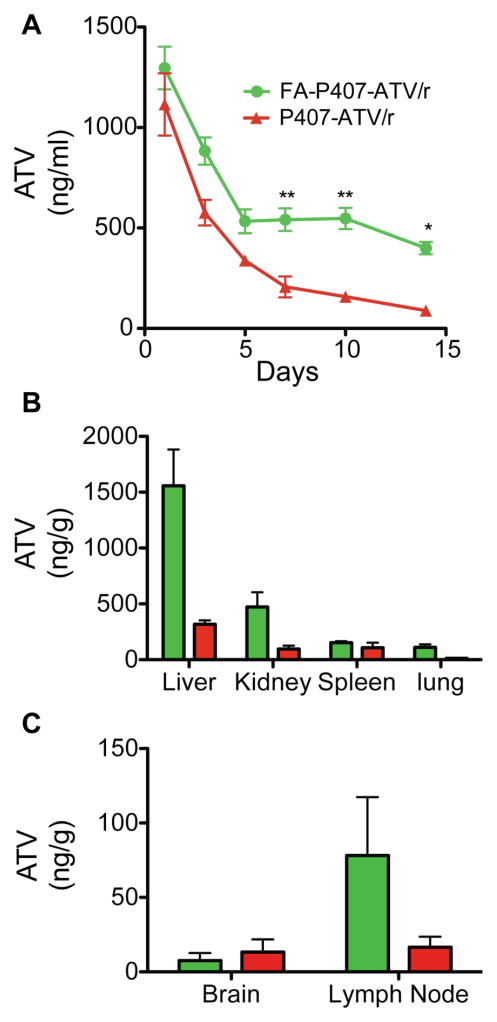

Balb/cJ mice were administered 50 or 100 mg/kg nanoformulated ATV/r to determine the pharmacokinetic parameters for both FA-coated and uncoated nanoART. Plasma and tissue drug concentrations following FA-nanoART treatment were higher compared to uncoated nanoART by day 14 (Figure 5). In mice treated with 50 mg/kg FA-nanoART ATV/r plasma concentrations were 400 ng/ml and 89 ng/ml, respectively (Figure 5A). ATV levels in liver, kidney and spleen were 3125 ng/g, 311.6 ng/g and 179.5 ng/g, respectively, in FA-nanoART treated mice compared to 317.7 ng/g, 96.5 ng/g and 107.6 ng/g in mice treated with uncoated nanoART at day 14 (Figure 5B). In addition, the ATV levels in lymph nodes were 78.2 ng/g following FA-nanoART treatment compared to 16.6 ng/g following treatment with uncoated nanoART (Figure 5C). The plasma and tissue levels of RTV are reported in supplementary figures (Figure S1A–C). Also, the ATV and RTV levels with 100 mg/kg FA-coated nanoART are shown in Figure S2A–D.

Figure 5. Comparison of pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of FA-P407-nanoART and P407-nanoART in mice.

Balb/cJ mice were administered 50 mg/kg (each drug) FA-P407-ATV/r or P407-ATV/r by intramuscular injection. (A) Plasma and (B, C) tissues were collected at indicated days and ATV levels determined by UPLC-MS/MS. Data are means ± SEM.

Discussion

Mononuclear phagocytes (MP; monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells) are efficient carrier systems that can deliver nanoART to target tissues such as liver, kidney, brain, spleen, lymph nodes, and lung. Cell-mediated drug delivery is a promising approach for patients with HIV because of these advantages. Nanomedicine offers further promises that include amelioration of drug toxicity, improved drug targeting, sustained delivery, and protection against metabolism. Therefore, packaging antiretroviral drugs as nanoformulations and delivering them to sites of ongoing viral infection using immune cells as carriers could provide a novel drug delivery system for use in HIV. This approach is termed nanoART.16

HIV patients are required to take oral antiretrovirals daily, and adherence of patients to the treatment regimen is difficult. Nanoformulations could address these limitations and could provide a sustained release drug delivery system through cell-based delivery. However, low uptake into macrophages and low therapeutic concentrations in lymph nodes, CNS, and other tissues are still significant limitations.15,18,33 Therefore, this study focused on developing and characterizing a targeted nanoART for macrophage uptake. We targeted the folate receptor (FOLR2) on macrophages, the expression of which was increased with activation of the cells. Because HIV-1 infection results in activation of immune cells, targeting the folate receptor on macrophages could provide enhanced cell uptake in infected individuals. Our results demonstrate that a FA-polymer coating on antiretroviral crystals improved the cell uptake and antiretroviral activity of the nanoformulations.

FA-P407 nanosuspensions from which the free FA-P407 polymer was not separated did not show a significant difference in uptake compared to non-targeted nanoART in MDMs. Our results demonstrated that this lack of difference was due to competition for folate receptor binding by excess free FA-P407 polymer that was not coated onto nanoART. Removal of this unincorporated FA-polymer and FA-polymer micelles resulted in a 2-fold greater uptake of the FA-nanoART purified nanosuspensions by MDMs compared to non-purified nanosuspensions and non-targeted nanoART. Therefore, all targeted nanosuspensions were purified for further experiments.

The FA-P407-ATV nanoparticles are taken up by macrophages by phagocytosis and receptor-mediated endocytosis. Phagocytosis occurs through a non-specific FcR-mediated pathway whereas endocytosis of FA-nanoART is a specific internalization mechanism involving FOLR. FcR binds to the Fc portion of IgG in an immune complex with the nanoparticle. FOLR2, binds the folic acid moieties on the FA-P407-nanoART. Here, we found that the FA-nanoART showed a significantly increased uptake compared to the non-targeted nanoART through binding to FOLR2 on macrophages. Indeed, folate-mediated endocytosis was verified by the inhibition of FA-coated nanoparticle uptake by free folic acid (Figure 3D). Both targeted and non-targeted nanoART are also taken up non-specifically by the macrophages through FcR mediated phagocytosis and clathrin-mediated endocytosis.19 Additionally, the amount of drug retained in the macrophages was higher compared to non-targeted nanoART. This was due to the ≥ 2-fold greater uptake of FA-nanoART than uncoated nanoART. This enabled drug release to continue >15 days. The amount of drug released into the media was sustained and at similar levels for all the nanoformulations, ~ 5 μg/ml. Also, pretreatment with folic acid inhibited the drug uptake therefore demonstrating that the uptake was through the folate receptor. In addition, there was no toxicity or decrease in cell viability with the tested nanoART concentrations. Because of enhanced uptake, retention, and a sustained release of drug over 15 days, the FA-nanoART showed stronger antiretroviral activity than non-targeted nanoART as confirmed by HIV-1 p24 staining and RT activity. The protection against the HIV-1ADA was seen for 15 days, unlike the non-targeted nanoART. Therefore, FA-nanoART could provide a sustained antiviral activity in vivo.

We investigated the intracellular co-localization of non-targeted and targeted nanoART in macrophages. We found that recycling endocytic compartments (Rab 11) take up a higher percent of nanoART as compared to the degrading compartments (lysosomes). Folate conjugated particles are bound and then internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis. However, the exact pathways that regulate internalization of folate conjugates are still controversial.34–36 Irrespective of the mechanism of internalization, folate conjugated nanoparticles move to endosomes 37 and at latter stages fuse with acidic compartments of the cell. Our subcellular localization results support two important observations. First, they confirmed that the macrophage takes up more FA-nanoART than non-targeted nanoART. These results are supported by our quantitative uptake studies with FA-nanoART (Figure 4A). Second, nanoART were protected inside the cell in Rab11 and Rab14 recycling endosomal compartments. These protection mechanisms could be part of the reason behind sustained activity of the FA-nanoART. It is interesting to note that the HIV-1 virus escapes lysosomal pathways and undergoes sorting before release via Rab11 recycling endosomal pathways as previously shown.19 This could be the reason for higher antiretroviral activity of FA-nanoART since the nanoART would have more accessibility to the virus in these endosomal compartments. However, not all nanoparticles that are taken up by the cells end up in Rab11 or Rab14 recycling endosomes. Some are associated with degrading lysosomal compartments. Modifications of the formulations that limit entry into lysosomal compartments and subsequent drug degradation could further improve nanoART efficacy.

To investigate the in vivo pharmacokinetic parameters of FA-P407-nanoART compared with P407-nanoART, we injected the mice with a dose of 50 mg/kg FA-P407-ATV/r nanoART and P407-ATV/r nanoART. The folate coating increased the plasma levels of ATV by approximately 5 times compared with no coating. Such parallels were also noticed in the tissue levels of ATV. It is interesting to note that targeting of drug with folate coating was best seen in vivo. This might be a result of saturation of drug due to the administration of higher polymer concentrations in our in vitro assays. It is noteworthy that ATV was detected in lymph nodes with FA targeting. Hence, coating could reduce tissue viral sanctuaries by permitting sustained tissue drug levels.

This study demonstrates that targeting macrophage receptors using ligands placed onto nanoART particles enhanced antiretroviral activity, drug pharmacokinetics and biodistribution. Notably, coating nanoformulations with ligand-modified polymers directed to macrophage receptors enhanced drug particle uptake, retention, and efficacy of the antiretroviral nanoformulations. Further studies are underway to determine whether FA-nanoART could provide improved antiretroviral activities and reductions in CD4+ T cell losses in relevant animal models for HIV infection. Although the FOLR is expressed on a variety of cells, facilitated uptake is demonstrable in those with phagocytic capacity. Altogether, FA coating of nanoART shows clear improvements for macrophage particle uptake, retention, and release of ART and as such shows substantive potential for human use.

Supplementary Material

Balb/cJ mice were administered 50 mg/kg (each drug) FA-P407-ATV/r or P407-ATV/r by intramuscular injection. (A) Plasma and (B, C) tissues were collected at indicated days and RTV levels determined by UPLC-MS/MS. Data are means ± SEM.

Balb/cJ mice were administered 100 mg/kg (each drug) FA-P407-ATV/r or P407-ATV/r by intramuscular injection. (A) Plasma and (B) tissues were collected at indicated days and ATV levels determined by UPLC-MS/MS. (C) Plasma and (D) tissues levels of RTV determined by UPLC-MS/MS. Data are means ± SEM.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Carol Swarts Neuroscience Research Laboratory, the Frances and Louie Blumkin Foundation and National Institutes of Health grants P01 DA028555, R01 NS36126, P01 NS31492, 2R01 NS034239, P01 MH64570, P01 NS43985 (H.E.G.) and 9P20GM103480 (T.B.).

The authors thank Ms. Janice Taylor of the UNMC Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy Core and Dr. Elizabeth Kosmacek for assistance in analyzing the confocal microscopy images and Ms. Hannah Baldridge for technical assistance. The authors also thank the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Electron Microscopy Core for supplying the scanning electron microscopy images.

List of abbreviations

- nanoART

nanoformulated antiretroviral therapeutics

- FA

folic acid

- FOLR

folate receptor

- MDM

monocyte-derived macrophages

- ATV

atazanavir

- RTV

ritonavir

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- PDI

polydispersity index

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- LAMP

lysosomal associated membrane protein

- RME

receptor-mediated endocytosis

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Pavan Puligujja, Email: pavan.puligujja@unmc.edu.

JoEllyn McMillan, Email: jmmcmillan@unmc.edu.

Lindsey Kendrick, Email: lindsey.kendrick@unmc.edu.

Tianyuzi Li, Email: tianyuzi.li@unmc.edu.

Shantanu Balkundi, Email: sbalkundi@unmc.edu.

Nathan Smith, Email: nathana.smith@unmc.edu.

Ram S. Veerubhotla, Email: ram.veerubhotla@unmc.edu.

Benson J. Edagwa, Email: benson.edagwa@unmc.edu.

Alexander V. Kabanov, Email: kabanov@email.unc.edu.

Tatiana Bronich, Email: tbronich@unmc.edu.

Howard E. Gendelman, Email: hegendel@unmc.edu.

Xin-Ming Liu, Email: xliu@unmc.edu.

References

- 1.Este JA, Cihlar T. Current status and challenges of antiretroviral research and therapy. Antiviral Res. 2010;85:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao KS, Ghorpade A, Labhasetwar V. Targeting anti-HIV drugs to the CNS. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:771–784. doi: 10.1517/17425240903081705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fogarty L, Roter D, Larson S, Burke J, Gillespie J, Levy R. Patient adherence to HIV medication regimens: a review of published and abstract reports. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:93–108. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chesney M. Adherence to HAART regimens. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003;17:169–177. doi: 10.1089/108729103321619773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volberding PA, Deeks SG. Antiretroviral therapy and management of HIV infection. Lancet. 2010;376:49–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartlett JA, Shao JF. Successes, challenges, and limitations of current antiretroviral therapy in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:637–649. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blankson JN, Persaud D, Siliciano RF. The challenge of viral reservoirs in HIV-1 infection. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:557–593. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balkundi S, Nowacek AS, Veerubhotla RS, Chen H, Martinez-Skinner A, Roy U, Mosley RL, Kanmogne G, Liu X, Kabanov AV, Bronich T, McMillan J, Gendelman HE. Comparative manufacture and cell-based delivery of antiretroviral nanoformulations. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:3393–3404. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S27830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowacek AS, McMillan J, Miller R, Anderson A, Rabinow B, Gendelman HE. Nanoformulated antiretroviral drug combinations extend drug release and antiretroviral responses in HIV-1-infected macrophages: implications for neuroAIDS therapeutics. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2010;5:592–601. doi: 10.1007/s11481-010-9198-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nowacek AS, Miller RL, McMillan J, Kanmogne G, Kanmogne M, Mosley RL, Ma Z, Graham S, Chaubal M, Werling J, Rabinow B, Dou H, Gendelman HE. NanoART synthesis, characterization, uptake, release and toxicology for human monocyte-macrophage drug delivery. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2009;4:903–917. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dou H, Destache CJ, Morehead JR, Mosley RL, Boska MD, Kingsley J, Gorantla S, Poluektova L, Nelson JA, Chaubal M, Werling J, Kipp J, Rabinow BE, Gendelman HE. Development of a macrophage-based nanoparticle platform for antiretroviral drug delivery. Blood. 2006;108:2827–2835. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-012534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMillan J, Batrakova E, Gendelman HE. Cell delivery of therapeutic nanoparticles. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2011;104:563–601. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416020-0.00014-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batrakova EV, Gendelman HE, Kabanov AV. Cell-mediated drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2011;8:415–433. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2011.559457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabanov AV, Gendelman HE. Nanomedicine in the diagnosis and therapy of neurodegenerative disorders. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:1054–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dash PK, Gendelman HE, Roy U, Balkundi S, Alnouti Y, Mosley RL, Gelbard H, McMillan J, Gorantla S, Poluektova L. Long-acting nanoART elicits potent antiretroviral and neuroprotective responses in HIV-1-infected humanized mice. AIDS. 2012;26:2135–2144. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328357f5ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dou H, Grotepas CB, McMillan JM, Destache CJ, Chaubal M, Werling J, Kipp J, Rabinow B, Gendelman HE. Macrophage delivery of nanoformulated antiretroviral drug to the brain in a murine model of neuroAIDS. J Immunol. 2009;183:661–669. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nowacek AS, Balkundi S, McMillan J, Roy U, Martinez-Skinner A, Mosley RL, Kanmogne G, Kabanov AV, Bronich T, Gendelman HE. Analyses of nanoformulated antiretroviral drug charge, size, shape and content for uptake, drug release and antiviral activities in human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Control Release. 2011;150:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy U, McMillan J, Alnouti Y, Gautum N, Smith N, Balkundi S, Dash P, Gorantla S, Martinez-Skinner A, Meza J, Kanmogne G, Swindells S, Cohen SM, Mosley RL, Poluektova L, Gendelman HE. Pharmacodynamic and antiretroviral activities of combination nanoformulated antiretrovirals in HIV-1-infected human peripheral blood lymphocyte-reconstituted mice. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1577–1588. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadiu I, Nowacek A, McMillan J, Gendelman HE. Macrophage endocytic trafficking of antiretroviral nanoparticles. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2011;6:975–994. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kularatne SA, Low PS. Targeting of nanoparticles: folate receptor. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;624:249–265. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-609-2_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu J, Li Z, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. In vivo tumor suppression efficacy of mesoporous silica nanoparticles-based drug-delivery system: enhanced efficacy by folate modification. Nanomedicine. 2012;8:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nukolova NV, Oberoi HS, Cohen SM, Kabanov AV, Bronich TK. Folate-decorated nanogels for targeted therapy of ovarian cancer. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5417–5426. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Li J, Wang Y, Cho KJ, Kim G, Gjyrezi A, Koenig L, Giannakakou P, Shin HJ, Tighiouart M, Nie S, Chen ZG, Shin DM. HFT-T, a targeting nanoparticle, enhances specific delivery of paclitaxel to folate receptor-positive tumors. Acs Nano. 2009;3:3165–3174. doi: 10.1021/nn900649v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia W, Hilgenbrink AR, Matteson EL, Lockwood MB, Cheng JX, Low PS. A functional folate receptor is induced during macrophage activation and can be used to target drugs to activated macrophages. Blood. 2009;113:438–446. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-150789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gendelman HE, Orenstein JM, Martin MA, Ferrua C, Mitra R, Phipps T, Wahl LA, Lane HC, Fauci AS, Burke DS, et al. Efficient isolation and propagation of human immunodeficiency virus on recombinant colony-stimulating factor 1-treated monocytes. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1428–1441. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balkundi S, Nowacek AS, Roy U, Martinez-Skinner A, McMillan J, Gendelman HE. Methods development for blood borne macrophage carriage of nanoformulated antiretroviral drugs. J Vis Exp. 2010 doi: 10.3791/2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng Y, Shen J, Streaker ED, Lockwood M, Zhu Z, Low PS, Dimitrov DS. A folate receptor beta-specific human monoclonal antibody recognizes activated macrophage of rheumatoid patients and mediates antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R59. doi: 10.1186/ar3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalter DC, Nakamura M, Turpin JA, Baca LM, Hoover DL, Dieffenbach C, Ralph P, Gendelman HE, Meltzer MS. Enhanced HIV replication in macrophage colony-stimulating factor-treated monocytes. J Immunol. 1991;146:298–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang J, Gautam N, Bathena SP, Roy U, McMillan J, Gendelman HE, Alnouti Y. UPLC-MS/MS quantification of nanoformulated ritonavir, indinavir, atazanavir, and efavirenz in mouse serum and tissues. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879:2332–2338. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manders E, Verbeek F, Aten J. Measurement of co-localization of objects in dual colour confocal images. J Microsc. 1993;169:375–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1993.tb03313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hattori Y, Sakaguchi M, Maitani Y. Folate-linked lipid-based nanoparticles deliver a NFkappaB decoy into activated murine macrophage-like RAW264. 7 cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:1516–1520. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Puig-Kroger A, Sierra-Filardi E, Dominguez-Soto A, Samaniego R, Corcuera MT, Gomez-Aguado F, Ratnam M, Sanchez-Mateos P, Corbi AL. Folate receptor beta is expressed by tumor-associated macrophages and constitutes a marker for M2 anti-inflammatory/regulatory macrophages. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9395–9403. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanmogne GD, Singh S, Roy U, Liu X, McMillan J, Gorantla S, Balkundi S, Smith N, Alnouti Y, Gautam N, Zhou Y, Poluektova L, Kabanov A, Bronich T, Gendelman HE. Mononuclear phagocyte intercellular crosstalk facilitates transmission of cell-targeted nanoformulated antiretroviral drugs to human brain endothelial cells. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:2373–2388. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S29454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayor S, Rothberg KG, Maxfield FR. Sequestration of GPI-anchored proteins in caveolae triggered by cross-linking. Science. 1994;264:1948–1951. doi: 10.1126/science.7516582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothberg KG, Ying YS, Kamen BA, Anderson RG. Cholesterol controls the clustering of the glycophospholipid-anchored membrane receptor for 5-methyltetrahydrofolate. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2931–2938. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu M, Fan J, Gunning W, Ratnam M. Clustering of GPI-anchored folate receptor independent of both cross-linking and association with caveolin. J Membr Biol. 1997;159:137–147. doi: 10.1007/s002329900277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turek JJ, Leamon CP, Low PS. Endocytosis of folate-protein conjugates: ultrastructural localization in KB cells. J Cell Sci. 1993;106 ( Pt 1):423–430. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Balb/cJ mice were administered 50 mg/kg (each drug) FA-P407-ATV/r or P407-ATV/r by intramuscular injection. (A) Plasma and (B, C) tissues were collected at indicated days and RTV levels determined by UPLC-MS/MS. Data are means ± SEM.

Balb/cJ mice were administered 100 mg/kg (each drug) FA-P407-ATV/r or P407-ATV/r by intramuscular injection. (A) Plasma and (B) tissues were collected at indicated days and ATV levels determined by UPLC-MS/MS. (C) Plasma and (D) tissues levels of RTV determined by UPLC-MS/MS. Data are means ± SEM.