Abstract

Insulin resistance (IR) underlines aging and aging-associated medical (diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension) and psychiatric (depression, cognitive decline) disorders (AAMPD). Molecular mechanisms of IR in genetically or metabolically predisposed individuals remain uncertain. Current review of literature and our data presents the evidences that dysregulation of tryptophan (TRP) – kynurenine (KYN) and KYN – nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) metabolic pathways is one of the mechanisms of IR. First and rate-limiting step of TRP – KYN pathway is regulated by enzymes inducible by pro-inflammatory factors and/or stress hormones. The key enzymes of KYN – NAD pathway require pyridoxal-5-phosphate (P5P), an active form of vitamin B6, as a co-factor. Deficiency of P5P diverts KYN – NAD metabolism from production of NAD to the excessive formation of xanthurenic acid (XA). Human and experimental studies suggested that XA and some other KYN metabolites might impair production, release and biological activity of insulin. We propose that one of the mechanisms of IR is inflammation- and/or stress-induced up-regulation of TRP – KYN metabolism in combination with P5P deficiency-induced diversion of KYN – NAD metabolism towards formation of XA and other KYN derivatives affecting insulin activity. Monitoring of KYN/P5P status and formation of XA might help to identify subjects-at-risk for IR. Pharmacological regulation of the TRP – KYN and KYN – NAD pathways and maintaining of adequate vitamin B6 status might contribute to prevention and treatment of IR in conditions associated with inflammation/stress–induced excessive production of KYN and deficiency of vitamin B6, e.g., diabetes type 2, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, aging, menopause, pregnancy, and hepatitis C virus infection.

Keywords: insulin resistance, tryptophan, kynurenines, xanthurenic acid, vitamin B6, inflammation, stress, interferon

Introduction

Insulin resistance (IR) underlines aging and aging-associated medical (diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension) and psychiatric (depression, cognitive decline) disorders (AAMPD)[1,2]. Molecular mechanisms of IR in genetically or metabolically predisposed individuals remain uncertain. Current review of literature and our data presents the evidences that dysregulation of tryptophan (TRP) – kynurenine (KYN) and KYN – nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) metabolic pathways is one of the mechanisms of IR. First and rate-limiting step of TRP – KYN pathway is regulated by enzymes inducible by pro-inflammatory factors and/ or stress hormones. The key enzymes of KYN – NAD pathway require pyridoxal-5-phosphate (P5P), an active form of vitamin B6, as a co-factor. Deficiency of P5P diverts KYN – NAD metabolism from production of NAD to excessive formation of xanthurenic acid (XA). Human and experimental studies revealed that XA and some other KYN metabolites might impair production, release and biological activity of insulin.

We propose that one of the mechanisms of IR is inflammation- and/or stress-induced up-regulation of TRP – KYN metabolism in combination with P5P deficiency-induced diversion of KYN – NAD metabolism towards formation of XA and other KYN derivatives affecting insulin activity.

Tryptophan – kynurenine metabolic pathway

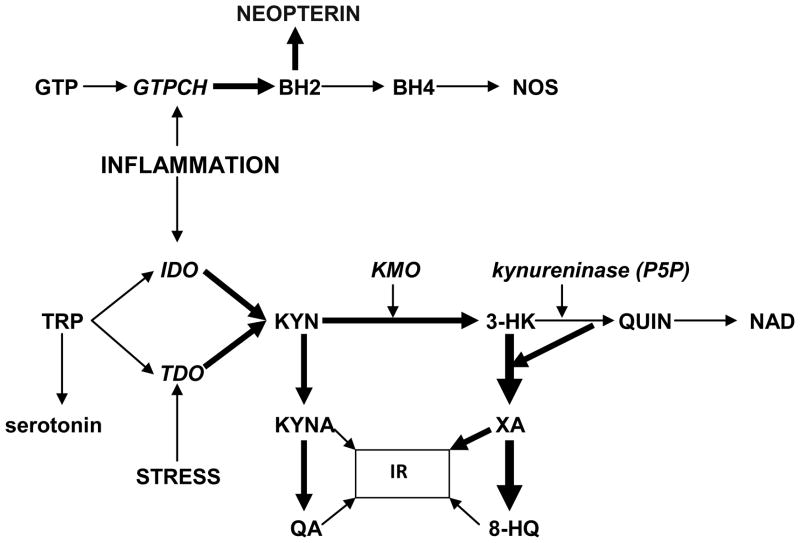

Tryptophan (TRP) is an essential (for humans) amino acid. About 5 % of non-protein route of TRP metabolism is utilized for formation of methoxyindoles: serotonin, N-acetylserotonin and melatonin [3, 4] (Fig.1).

Fig.1.

Vitamin B6 deficiency-induced shift of post-KYN metabolism from biosynthesis of NAD towards formation of diabetogenic KYN derivatives.

Abbreviations. IR – insulin resistance; TRP – tryptophan; IFNG – interferon-gamma; IDO – indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; KYN – kynurenine; KMO – KYN-3-monooxygenase; 3-HK – 3-hydroxyKYN; P5P – pyridoxal 5′-phosphate; QUIN – quinolinic acid; NAD – nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; KYNA – kynurenic acid; XA – xanthurenic acid; QA - quinaldic acid; 8-HQ – 8-hydroxyquinaldic acid; GTP – guanosine triphosphate; GTPCH – GTP cyclohydrolase I; BH2 - 7,8-dihydroneopterin;. BH4 – tetrahydrobiopterin; NOS – nitric oxide synthase.

The major non-protein route of TRP metabolism is formation of KYN, catalyzed by rate-limiting enzymes: indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) or TRP 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) [4]. IDO is activated by pro-inflammatory mediators, e.g., interferon-gamma (IFNG), tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IL-1 beta, and lipopolysaccharide, while TDO is inducible by stress hormones, e.g., cortisol, estrogens, prolactin, and by substrate, TRP [3].

Kynurenine – nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide metabolic pathway

KYN is substrate for two post-KYN metabolic pathways: 1). Formation of kynurenic acid (KYNA), catalyzed by KYN aminotransferases (KAT). KYNA is a precursor of quinaldic acid (QA) [5]; and 2). Formation of 3-hydroxyKYN (3-HK) catalyzed by KYN 3-monooxygenase [3,4].

3-HK is a substrate for two metabolic pathways: 1). Formation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD). The first step of the 3-HK – NAD pathway catalyzed by kynureninase; and 2). Formation of xanthurenic acid (XA), catalyzed by 3-HK-transaminase [6]. XA is a precursor of 8-hydroxyquinaldic acid (8-HQ) [7].

Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate and KYN – NAD metabolic pathway

Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (P5P), an active form of vitamin B6, is a cofactor for >100 metabolic reactions, including key enzymes of post-KYN metabolism: KYN 3-monooxygenase, KAT and kynureninase, the latter enzyme is particularly sensitive to dietary vitamin B-6 restriction [8]. Down-regulation of kynureninase, caused by P5P deficiency, shifts 3-HK metabolism from formation of NAD to production of XA and KA [9]. P5P deficiency combined with up-regulated TRP conversion to KYN leads to increased availability of 3-HK as a substrate for formation of XA and 8-HQ, and increased availability of KYN as a substrate for KYNA and QA in the cerebellum, corpus striatum, frontal cortex, and pons/medulla [10], blood [11], urine [12], pancreatic islets [13, 14].

Vitamin B6 depletion resulted in drastic increase while vitamin B6 supplementation normalized urinary 3-HK and XA after TRP load in cardiac [15] and obese [16] patients and rats [17]. Therefore, P5P deficiency combined with up-regulation of TRP – KYN pathway might divert KYN – NAD metabolism towards increased formation of XA at the expense of NAD production (Fig.1).

The other consequence of P5P deficiency-induced down-regulation of kynureninase is the decreased formation of NAD that leads to inhibition of synthesis and secretion of insulin and the death of pancreatic beta-cells [18]. Considering that NAD inhibits TDO, decreased formation of NAD caused by P5P deficiency, might lead to further activation of TDO and increased production of KYN) [19].

Besides P5P deficiency, kynureninase might be inhibited by XA, thus sustaining the accumulation of 3-HK, KYNA, KYN and XA at the expense of NAD production [20]. Additionally, XA might perpetuate P5P deficiency by inhibiting pyridoxal kinase, the enzyme catalyzing the formation of P5P from vitamin B6 [21].

It is noteworthy that vitamin B6 dose-dependently decreased insulin levels and improved insulin sensitivity in the experimental model of type 2 diabetes [22].

Diabetogenic effects of KYN derivatives

Xanthurenic acid

Increased urine excretion of XA was reported in type 2 diabetes patients in comparison with in healthy subjects [23]. Recent study found the increased levels of XA precursors, KYN and 3-HK in serum samples of diabetic retinopathy patients [24]. XA induced experimental diabetes in rats [25].

The possible mechanisms mediating XA contribution to the development of diabetes might be 1). Formation of chelate complexes with insulin (XA-In). As antigens, XA-In complexes are indistinguishable from insulin but have 49% lower activity than pure insulin [25]; 2). Formation of Zn++-ions – insulin complexes in β-cells that exert toxic effect in isolated pancreatic islets [26, 27]; 3). Inhibition of insulin release from rat pancreas [13]; and 4). Induction of pathological apoptosis of pancreatic beta cells through caspase-3 dependent mechanism [27,28].

Kynurenic acid

KYNA was found to be increased in urine of nonhuman primate and mouse models of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a recent metabolomic study [30], and in patients with diabetic retinopathy [24]. KYNA (in micromolar concentrations) was detected in pancreatic juice of pigs [31].

The possible mechanisms of diabetogenic effect of KYNA might be related to KYNA ability to block NMDA receptors. Thus, NMDA antagonist and pharmacological precursor of KYNA, 7-chlorokynurenic acid [4] and NMDA antagonist, MK-801, negated the inhibition of glucose production induced by NMDA agonists injected into dorsal vagal complex in rodents [32].

In addition, XA, KYNA, and their derivatives, QA and 8-HQ, (in millimolar concentrations) inhibit pro-insulin synthesis in isolated rat pancreatic islets [33]

Recent study revealed elevated expression of IDO in serum samples of diabetic retinopathy patients [24]. In the same vein, surplus dietary TRP, the substrate for formation of KYNA and XA, induced IR in pigs [34].

Clinical markers of up-regulation of TRP – KYN pathway

Plasma (serum) ratio of KYN to TRP (KTR) is a generally accepted clinical marker of IDO activity [11]. Considering that both IDO and TDO regulate the rate of TRP conversion into KYN [35], plasma concentrations of TRP and KYN might be affected by the activity of stress hormone inducible TDO as well. However, KTR does reflect IDO activity in conditions associated with inflammation (2).

Concurrently with induction of IDO, pro-inflammatory factors (e.g., IFNG, TNF-alpha, IL-1beta) induce guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase I (GTPCH), a rate-limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of tetrahydrobiopterine (BH4), the obligatory cofactor of nitric oxide (NO) synthase (NOS) [39]. GTPCH catalyzes GTP conversion into 7,8-dihydroneopterin (BH2) [36]. Pro-inflammatory factors-induced activation of GTPCH results in increased formation of neopterin, a stable, water-soluble derivative of BH2 [37]. Therefore, inflammation-induced elevation of neopterin production might be considered not simply a clinical marker of inflammation, but an indirect marker of IDO activation as well [36].

Blood neopterin levels correlate with KTR in healthy humans [38], and cardiovascular patients [11]. We found similar strong (r=0.68) and highly significant (p<0.0001) correlation between serum KTR ratio and neopterin in 80 hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients treated with interferon-alpha [unpublished data].

Kynurenine/tryptophan ratio, neopterin and P5P levels, and incidence of IR in clinical conditions associated with chronic inflammation and stress

Diabetes

Clinical and experimental data suggest the increased metabolism of TRP in diabetes, resulting most likely, from up-regulation of TRP – KYN pathway. Thus, impaired accumulation of TRP in the brain concomitantly with a much faster disappearance of the administered TRP from the bloodstream was observed in streptozotocin-diabetic rats after TRP load [39]. Similarly, post-loading levels of plasma TRP (but not of other large neutral amino acids) were lower in diabetic patients than in healthy controls. [40]

Recent studies reveal decreased plasma TRP concentrations and increased KYN and KTR in 21 hemodialysis patients with diabetes in comparison with 40 healthy controls patients. An increase in neopterin was correlated with KYN concentrations (r = 0.393, p < 0.01), suggesting that increased TRP degradation is a result of IDO activation [41]. In the same vein, neopterin but not C-reactive protein, an inflammation marker not related to IDO/GTPCH activation, increased in diabetic in comparison with non-diabetic patients with critical limb ischemia [42].

Decreased kynureninase activity was observed in liver and kidney of alloxan diabetic rabbits [43]. Additionally, XA was identified in pre-diabetes subjects [44].

Neopterin correlated with IR, an early event in the pathogenesis of type 2-diabetes, in Caucasian population [11,45,46]. We observed correlation between plasma neopterin concentrations and IR (HOMA-IR, r=0.08, P <0.03), and P5P (r =−0.13, P = 0.002) in 592 adult (45–75 years of age) participants of community dwellers in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. The strongest (r=0.15) and most significant (P<0.0002) correlation was recognized between HOMA-IR and neopterin/P5P ratio (a combined index of increased inflammation and P5P deficiency) [47]. Low plasma concentrations of P5P have been reported in conditions associated with increased fasting glucose and glycated hemoglobin [48].

Obesity

Obesity represents a major risk factor for the development of IR [49], and is considered an independent cause of IR [50]. In most cases IR exists because of the obesity and will disappear with weight loss [51]. Human obesity is characterized by chronic low-grade inflammation in white adipose tissue that releases many inflammatory mediators, including KYN [52,53]. Serum KTR and IDO expression in omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues and liver were higher in obese than in lean women [54]. KTR and neopterin and inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein, were increased in morbid obese subjects [55]. However, only neopterin and KTR did not normalize after bariatric surgery and weight loss [55]. These studies suggested that IFNG-induced IDO and GTPCH activities have unique role as the trait (VS state) inflammatory markers in obesity.

P5P deficiency was noted in 11% of morbid obese individuals before laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy [56]. Significantly lower P5P concentrations were reported in the morbidly obese Norwegian women and men [57].

Depression

The stress-induced TDO activation that shunts TRP metabolism from formation of serotonin towards production of KYN in depression was originally suggested in 1969 [58]. Discovery of inflammation-inducible IDO added another mechanism of up-regulation of KYN formation from TRP in depression [59]. Association of depression with the increased production of cortisol [60] and inflammatory factors [61] are described elsewhere. Both IDO and TDO activation leads to the same major consequences: 1). Deficiency of serotonin (and its metabolites, melatonin and N-acetylserotonin) contributing to insomnia, dysregulation of biological rhythms and impaired neurogenesis observed in depression [62–64]; 2). Up-regulated formation of KYN and its neuroactive derivatives exerting anxiogenic, pro-oxidative and cognitive impairment effects typical for depression [35,65,66].

Increased plasma neopterin levels were reported in depressed patients, further supporting the notion of IDO activation in depression [67]. Low plasma concentrations of P5P have been reported in depression (68). An increase in KTR and a deficiency in vitamin B6 might explain the increased production of XA in depressed patients (69). Although XA levels correlated with the severity of depression (69), elevation of serum XA is not specific for depression but, rather, a marker of P5P deficiency (9,11). However, supplementation with P5P did not normalize elevated XA levels in depressed patients (69).

The increased association between depression and IR (and diabetes) is generally acknowledged [70, 71]. Observation of a 65% increased risk of development of (mostly type 2) diabetes in a prospective study of clinically depressed patients [72] supports the hypothesis that depression leads to diabetes [73].

One of the mechanisms of the increased incidence of IR (and diabetes) in depressed subjects might be a combination of P5P deficiency with the up-regulation of TRP - KYN and dysregulation of KYN – NAD metabolic pathways.

The role of IFNG-inducible IDO in the mechanisms of major depression might be further supported by the strong correlation between increased serum KTR and severity of depression, developed as a side-effect of IFN-alpha treatment of HCV or melanoma patients [74]. We found that presence of high producer (T) allele of IFNG (+874) T/A gene that encodes the production of pro-inflammatory cytokine, IFNG, increases the risk of development of depression during IFN-alpha treatment [75]. Serum neopterin concentrations were higher in HCV versus the non-HCV patient population and predicted resistance to IFN-alpha therapy [76].

Hepatitis C virus

Incidence of IR among HCV patients is 50% that four-fold higher than in non-HCV population [77] HCV infection significantly lowered vitamin B6 [78]. Antecedent HCV infection markedly increases the risk of developing diabetes in susceptible subjects while even non-diabetic HCV patients have IR and specific defects in the insulin-signaling pathway [79]. IFN-alpha treatment was associated with the additional risk of IR (and type 2 diabetes) in comparison with the group of non-viral chronic liver disease [80] or patients with chronic hepatitis B virus [81]. Serum KTR and neopterin concentrations were higher in HCV patients than in non-HCV population [82]. These data are in line with the current hypothesis that increased risk of IR in HCV patients depends on combination of IFNG-induced up-regulation of TRP – KYN metabolism with P5P deficiency-induced dysregulation of KYN – NAD metabolic pathway.

Aging

IR was originally suggested as mechanism of aging by VM Dilman [83–86]. IR is the key factor of aging metabolic syndrome [87]. Aging is associated with vitamin B6 deficiency [88, 89] and increased plasma neopterin and KTR [46, 90]. Up-regulation of TRP – KYN metabolism in aging might results both from activation of IDO due to age-associated chronic inflammation [2] and/or TDO due to age-associated elevation of cortisol production [3, 84].

XA accumulates in organs with aging and activates caspase-9 and -3 leading to apoptosis of pancreatic beta cells [28].

Other conditions associated with insulin resistance

Cardiovascular disease

IR, increased KYN and neopterin production and vitamin B6 deficiency were reported in cardiovascular disease [11, 91,92].

Menopause

Menopause is associated with IR [83,84,93,94]. Production of IFNG, the most powerful activator of IDO, was increased in postmenopausal women [95]. Partial impairment in P5P-dependent kynureninase (suggesting shift to increased production of diabetogenic XA (Fig.1) was observed in postmenopausal women [90]. This enzymatic activity could be partially restored by vitamin B6 supplementation [96].

Pregnancy and gestations

Up-regulation of TRP–KYN metabolism [97,98] and vitamin B6 deficiency [8] might contribute to the development of gestational diabetes. Administration of vitamin B6 improved oral glucose tolerance in gestational diabetes [99].

Therapeutic interventions

Current hypothesis suggests that prevention and treatment of IR in conditions associated with chronic stress or chronic inflammation should include a combination of vitamin B6 dietary supplementation and pharmacological modifications of TRP – KYN metabolism, aimed on down-regulation of the formation of diabetogenic KYN derivatives. The latter may be achieved by administration of IDO/TDO inhibitors. The known IDO inhibitor, 1-methyl-L-TRY [100] is not available for human use. There are two indirect (via down-regulation of IFNG formation) IDO inhibitors available for human use: minocycline, an antibiotic with anti-inflammatory action [101,102] and antidepressant, wellbutrin [103]. It is noteworthy that wellbutrin, contrary to tricyclic antidepressants, has a favorable metabolic profile [104]. Berberine, isoquinoline alkaloid isolated from Berberis aristata, a herb widely used in Indian and Chinese systems of medicine, inhibits IDO significantly stronger than 1-methyl-L-TRY [105] (Table 1). Berberine improves IR in diabetic hamsters [106] and diabetic patients [107,108]. It is noteworthy that both berberine and minocycline prolonged life span and improved health span in Drosophila model [109,110]. Consistent with our hypothesis is observation that vitamin B6 supplementation dose-dependently decreased insulin levels and improved IR in KK-A(y) mice, an animal model of obese, type 2 diabetes [111,112].

Table 1.

The effect of therapeutics and natural products on kynurenine formation from tryptophan.

| berberine | minocycline | wellbutrin | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFNG (production) | ? | ↓ | ↓ |

| IDO (activity) | ↓ | ? | ? |

| TDO (activity) | ↓* | ? | ? |

Abbreviations. IFNG – interferon-gamma; IDO – indoleamine 2,3 - dioxygenase; TDO – tryptophan 2,3 -dioxygenase.

? - no data available;

no data available but probable because tryptophan is one of the substrates of IDO (but the only substrate for TDO).

Conclusions

Review of literature and our data suggests that inflammation or/and stress-induced upregulation of TRP – KYN metabolism, resulting in the excessive production of KYN, is one of the factors predisposing to IR. Deficiency of P5P, a co-factor of the key enzyme of KYN – NAD pathway, diverts the excessive amount of KYN from formation of NAD towards production of XA (and other) diabetogenic derivatives of KYN.

Monitoring of KYN/P5P status and formation of XA might help to identify subjects-at-risk for IR. Pharmacological regulation of the TRP – KYN and KYN – NAD pathways and maintaining of adequate vitamin B6 status might contribute to prevention and treatment of IR in conditions associated with inflammation/stress–induced excessive production of KYN and deficiency of vitamin B6, e.g., diabetes type 2, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, aging, menopause, pregnancy, and hepatitis C virus infection.

Acknowledgments

GF Oxenkrug is a recipient of NIMH099517 grant

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement. None

References

- 1.Esposito K, Giugliano D. The metabolic syndrome and inflammation: association or causation? Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2004;14:228–32. doi: 10.1016/s0939-4753(04)80048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oxenkrug GF. Interferon-gamma-inducible kynurenines/pteridines inflammation cascade: implications for aging and aging-associated medical and psychiatric disorders. J Neural Transm. 2011;118:75–85. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0475-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oxenkrug GF. Genetic and hormonal regulation of the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism: new target for clinical intervention in vascular dementia, depression and aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1122:35–49. doi: 10.1196/annals.1403.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwarcz R, Bruno JP, Muchowski PJ, Wu HQ. Kynurenines in the mammalian brain: when physiology meets pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:465–477. doi: 10.1038/nrn3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi H, Kaihara M, Price JM. The conversion of kynurenic acid to quinaldic acid by human and rats. J Biol Chem. 1956;223:705–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogasawara N, Hagino Y, Kotake Y. Kynurenine-transaminase, kynureninase and the increase of xanthurenic acid excretion. J Biochem. 1962;52:162–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a127591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi H, Price JM. Dehydroxylation of Xanthurenic Acid to 8-Hydroxyquinaldic Acid. J Biol Chem. 1956;233:150–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamp van de JL, Smolen A. Response of kynurenine pathway enzymes to pregnancy and dietary level of vitamin B-6. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;51:753–84. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00026-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bender DA, Njagi EN, Danielian PS. Tryptophan metabolism in vitamin B6-deficient mice. Br J Nutr. 1990;63:27–36. doi: 10.1079/bjn19900089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guilarte TR, Wagner HN., Jr Increased concentrations of the endogenous tryptophan metabolite 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) were measured in the brains of vitamin B6 deficient neonatal rats. J Neurochemistry. 1987;49:1918–1926. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb02455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Midttun O, Ulvik A, Pedersen E, Ebbing M, Bleie O, et al. Low Plasma Vitamin B-6 Status Affects Metabolism through the Kynurenine Pathway in Cardiovascular Patients with Systemic Inflammation. J Nutr. 2011;141:611–7. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.133082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimoto M, Ogawa T, Tokushima Sasaoka K. Accumulation of 3-hydroxy-L-kynurenine sulfate and ethanolamine in urine of the rat injected with 1-aminoproline. J Exp Med. 1991;38:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers KS, Evangelista SJ. 3-Hydroxykynurenine, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, and o-aminophenol inhibit leucine-stimulated insulin release from rat pancreatic islets. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1985;178:275–8. doi: 10.3181/00379727-178-42010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarkar SA, Wong R, Hackl SI, Moua O, Gill RC, et al. Induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by interferon-gamma in human islets. Diabetes. 2007;56:72–79. doi: 10.2337/db06-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudzite V, Fuchs D, Kalnins U, Jurika E, Silava A, et al. Prognostic value of tryptophan load test followed by serum kynurenine determination. Its comparison with pyridoxal-5-phosphate, kynurenine, homocysteine and neopterin amounts. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;527:307–15. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0135-0_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yess N, Price JM, Brown RR, Swan PB, Linkswiler H. Vitamin B6 depletion in man: urinary excretion of tryptophan metabolites. J Nutr. 1964;84:229–36. doi: 10.1093/jn/84.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsubouchi R, Izuta S, Shibata Y. Kynurenine metabolism and xanthurenic acid formation in vitamin B6-deficient rat after tryptophan injection. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1989;35:111–22. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.35.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okamoto H. Recent advances in physiological and pathological significance of tryptophan – NAD metabolites: lessons from insulin-producing pancreatic beta-cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;527:243–252. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0135-0_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho-Chung YS, Pitot HC. Feedback control of liver tryptophan pyrrolase. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shibata Y, Ohta T, Nakatsuka M, Ishizu H, Matsuda Y, et al. Taurine and kynureninase. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 1996;40:55–58. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0182-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeuchi F, Tsubouchi R, Shibata Y. Effect of tryptophan metabolites on the activities of rat liver pyridoxal kinase and pyridoxamine 5-phosphate oxidase in vitro. Biochem J. 1985;227:537–44. doi: 10.1042/bj2270537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murakoshi M, Tanimoto M, Gohda T, Hagiwara S, Ohara I, et al. Pleiotropic effect of pyridoxamine on diabetic complications via CD36 expression in KK-Ay/Ta mice. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009. 2009;83:183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hattori M, Kotake Y, Kotake Y. Studies on the urinary excretion of xanthurenic acid in diabetics. Acta Vitaminol Enzymol. 1984;6:221–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munipally PK, Agraharm Satish G, Valavala Vijay Kumar, Gundae Sridhar, Turlapati Naga Raju. Evaluation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression and kynurenine pathway metabolites levels in serum samples of diabetic retinopathy patients. Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry. 2011;117(5):254–258. doi: 10.3109/13813455.2011.623705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotaki Y, Ueda T, Mori T, Igaki S, Hattori M. Abnormal tryptophan metabolism and experimental diabetes by xanthurenic acid (XA) Acta Vitaminol Enzymol. 1975;29:236–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyramov G, Korchin V, Kocheryzkina N. Diabetogenic activity of xanturenic acid determined by its chelating properties? Acta Vitaminol Enzymol. 1984;6:221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00788-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikeda S, Kotake Y. Urinary excretion of xanthurenic acid and zinc in diabetes: (3). Occurrence of xanthurenic acid-Zn2+ complex in urine of diabetic patients and of experimentally-diabetic rats. Ital J Biochem. 1986;35:232–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malina HZ, Richter C, Mehl M, Hess OM. Pathological apoptosis by xanthurenic acid, a tryptophan metabolite: activation of cell caspases but not cytoskeleton breakdown. BMC Physiol. 2001;1:7–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q, Chen J, Wang Y, Han X, Chen X. Hepatitis C virus induced a novel apoptosis-like death of pancreatic beta cells through a caspase 3-dependent pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patterson AD, Bonzo JA, Li F, Krausz KW, Eichler GS, Aslam S, Tigno X, Weinstein JN, Hansen BC, Idle JR, Gonzalez FJ. Metabolomics reveals attenuation of the SLC6A20 kidney transporter in nonhuman primate and mouse models of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(22):19511–2233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.221739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuc D, Zgrajka W, Parada-Turska J, Urbanik-Sypniewska T, Turski WA. Micromolar concentration of kynurenic acid in rat small intestine. Amino Acids. 2008;35:503–505. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0631-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lam CK, Chari M, Su BB, Cheung GW, Kokorovic A, Yang CS, Wang PY, Lai TY, Lam TK. Activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in the dorsal vagal complex lowers glucose production. J Biol Chem. 2010 Jul 16;285(29):21913–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.087338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noto Y, Okamoto H. Inhibition by kynurenine metabolites of proinsulin synthesis in isolated pancreatic islets. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1978;15:273–82. doi: 10.1007/BF02590750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koopmans SJ, Ruis M, Dekker R, Korte M. Surplus dietary tryptophan inhibits stress hormone kinetics and induces insulin resistance in pigs. Physiol Behav. 2009;98:402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oxenkrug G. Tryptophan–kynurenine metabolism as a common mediator of genetic and environmental impacts in major depressive disorder: Serotonin hypothesis revisited 40 years later. Israel J Psychiatry. 2010;47:56–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sucher R, Schroecksnadelb K, Weissb G, Margreitera R, Fuchs D, Brandacher G. Neopterin, a prognostic marker in human malignancies. Cancer Letters. 2010;287:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neurauter G, Schröcksnadel K, Scholl-Bürgi S, Sperner-Unterweger B, Schubert C, et al. Chronic Immune Stimulation Correlates with Reduced Phenylalanine Turnover. Current Drug Metabolism. 2008;9:622–627. doi: 10.2174/138920008785821738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frick B, Schroecksnadel K, Neurauter G. Increasing production of homocysteine and neopterin and degradation of tryptophan with older age. Clin Biochem. 2004;37:684–687. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masiello P, Balestreri E, Bacciola D, Bergamini E. Influence of experimental diabetes on brain levels of monoamine neurotransmitters and their precursor amino acids during tryptophan loading. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1987;24:43–50. doi: 10.1007/BF02732052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fierabracci V, Novelli M, Ciccarone AM, Masiello P, Benzi L, Navalesi R, Bergamini E. Effects of tryptophan load on amino acid metabolism in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab. 1996;22:51–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koenig P, Nagl C, Neurauter G, Schennach H, Brandacher G, Fuchs D. Enhanced degradation of tryptophan in patients on hemodialysis. Clin Nephrol 2010. 2010;74:465–70. doi: 10.5414/cnp74465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertz L, Barani J, Gottsäter A, Nilsson PM, Mattiasson I, Lindblad B. Are there differences of inflammatory bio-markers between diabetic and non-diabetic patients with critical limb ischemia? Int Angiol. 2006 Dec;25(4):370–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allegri G, Zaccarin D, Ragazzi E, Froldi G, Bertazzo A, Costa CV. Metabolism of tryptophan along the kynurenine pathway in alloxan diabetic rabbits. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;527:387–93. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0135-0_45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manusadzhian VG, Kniazev IuA, Vakhrusheva LL. Mass spectrometric identification of xanthurenic acid in pre-diabetes. Vopr Med Khim. 1974;20:95–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ledochowski M, Murr C, Widner B, Fuchs D. Association between insulin resistance, body mass and neopterin concentrations. Clin Chim Acta. 1999;282:115–23. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(99)00019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schennach H, Murr C, Gächter E, Mayersbach P, Schönitzer D, Fuchs D. Factors Influencing Serum Neopterin Concentrations in a Population of Blood Donors. Clinical Chemistry. 2002;48:643–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oxenkrug G, Tucker KL, Requintina P, Summergrad P. Neopterin, a marker of interferon-gamma-inducible inflammation, correlates with pyridoxal-5′-phosphate, waist circumference, HDL-cholesterol, insulin resistance and mortality risk in adult Boston community dwellers of Puerto Rican origin. American Journal of Neuroprotection and Neuroregeneration. 2011;3:48–52. doi: 10.1166/ajnn.2011.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen J, Lai CQ, Mattei J, Ordovas JM, Tucker KL. Association of vitamin B-6 status with inflammation, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammatory conditions: the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:337–342. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Könner AC, Brüning JC. Selective insulin and leptin resistance in metabolic disorders. Cell Metab. 2012;16:144–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Szybiński Z, Szurkowska M. Insulinemia--a marker of early diagnosis and control of efficacy of treatment of type II diabetes. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2001;106:793–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Di Betta E, Mittempergher F, Terraroli C, Valloncini E, Salerni B. Severe obesity and insulin resistance. Result obtained by the bilio-pancreatic diversionin dependentely for an associated gastroresection or gastropreservation. Ann Ital Chir. 2007;78:201–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watts SW, Shaw S, Burnett R, Dorrance AM. Indoleamine 2,3-diooxygenase in periaortic fat: mechanisms of inhibition of contraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1236–47. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00384.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scarpellini E, Tack J. Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome: An Inflammatory Condition. Dig Dis. 2012;30:148–53. doi: 10.1159/000336664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolowczuk I, Hennart B, Leloire A, Bessede A, Soichot M, et al. Tryptophan metabolism activation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in adipose tissue of obese women: an attempt to maintain immune homeostasis and vascular tone. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;303:R135–43. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00373.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brandacher G. Chronic immune activation underlies morbid obesity: is IDO a key player? Curr Drug Metab. 2007;8:289–295. doi: 10.2174/138920007780362590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Damms-Machado A, Friedrich A, Kramer KM, Stingel K, Meile T, Küper MA, Königsrainer A, Bischoff SC. Pre- and Postoperative Nutritional Deficiencies in Obese Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2012 Mar 9; doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0609-0. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aasheim ET, Hofsø D, Hjelmesaeth J, Birkeland KI, Bøhmer T. Vitamin status in morbidly obese patients: a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:362–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.2.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lapin IP, Oxenkrug GF. Intensification of the central serotoninergic processes as a possible determinant of the thymoleptic effect. Lancet. 1969;1:32–39. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)91140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hayaishi O. Properties and function of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1976;79:13P–21P. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leonard BE. The HPA and immune axes in stress: The involvement of the serotoninergic system. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:S302–S306. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(05)80180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Leonard BE, Myint A. The psychoneuroimmunology of depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:165–175. doi: 10.1002/hup.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oxenkrug GF, Requintina PJ. Melatonin and jet lag syndrome: experimental model and clinical implications. CNS Spectrums. 2003;8:139–148. doi: 10.1017/s109285290001837x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oxenkrug G. Interferon-gamma – Inducible Inflammation: Contribution to Aging and Aging-Associated Psychiatric Disorders. Aging and Disease. 2011;2:474–486. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oxenkrug G, Ratner R. N-Acetylserotonin and Aging-Associated Cognitive Impairment and Depression. Aging and Disease. 2012;3:330–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lapin IP. Kynurenines as probable participants of depression. Pharmakopsychiatr Neuropsychopharmakol. 1973;6:273–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1094391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lapin IP. Neurokynurenines (NEKY) as common neurochemical links of stress and anxiety. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;527:121–125. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0135-0_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maes M. Depression is an inflammatory disease, but cell-mediated immune activation is the key component of depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:664–75. 7. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Merete C, Falcon LM, Tucker KL. Vitamin B6 is associated with depressive symptomatology in Massachusetts elders. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27:421–427. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cazzulo CL, Mangoni A, Mascherpa G. Tryptophan metabolism in affective psychoses. British J Psychiatry. 1974;112:157–162. doi: 10.1192/bjp.112.483.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Demakakos P, Pierce MB, Hardy R. Depressive symptoms and risk of type 2 diabetes in a national sample of middle-aged and older adults: the English longitudinal study of aging. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:792–7. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rustad JK, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB. The relationship of depression and diabetes: pathophysiological and treatment implications. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011. 2011;36:1276–86. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Campayo A, de Jonge P, Roy JF, Saz P, de la Camara C, et al. Depressive disorder and incident diabetes mellitus: the effect of characteristics of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:580–588. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eaton WW, Armenian H, Gallo J, Pratt L, Ford DE. Depression and risk for onset of type II diabetes. A prospective population-based study. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:1097–1102. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Capuron L, Miller AH. Immune system to brain signaling: neuropsychopharmacological implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;130:226–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oxenkrug G, Perianayagam M, Mikolich D, Requintina P, Shick L, et al. Interferon-gamma (+874) T/A genotypes and risk of IFN-alpha-induced depression. J Neural Transm. 2011;118:271–274. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0525-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oxenkrug GF, Requintina RJ, Mikolich DL, Ruthazer R, Viveiros K, et al. Neopterin as a Marker of Response to Antiviral Therapy in Hepatitis C Virus Patients. Hepatitis Research and Treatment. 2012;2012:4. doi: 10.1155/2012/619609. Article ID 619609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Negro F, Alaei M. Hepatitis C virus and type 2 diabetes. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1537–67. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lin CC, Yin MC. Vitamins B depletion, lower iron status and decreased antioxidative defense in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated by pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin. Clin Nutr. 2009;28:34–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Knobler H, Schattner A. TNF-alpha, chronic hepatitis C and diabetes: a novel triad. QJM. 2005;98:1–6. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brischetto R, Corno C, Amore MG, Leotta S, Pavone S, et al. Prevalence and significance of type-2 diabetes mellitus in chronic liver disease, correlated with hepatitis C virus. Ann Ital Med Int. 2003;18:31–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Imazeki F, Yokosuka O, Fukai K, Kanda T, Kojima H, Saisho H. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis C: comparison with hepatitis B virus-infected and hepatitis C virus-cleared patients. Liver Int. 2008;28:355–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fuchs D, Norkrans G, Wejsta R, Reibnegger G, Weiss G, et al. Changes of serum neopterin, beta 2-microglobulin and interferon-gamma in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with interferon-alpha 2b. Eur J Med. 1982;1:196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dilman VM. Age-associated elevation of hypothalamic, threshold to feedback control, and its role in development, ageing, and disease. Lancet. 1971;1:1211–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91721-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dilman VM, Lapin IP, Oxenkrug GF. In: Serotonin and aging. In Serotonin in health and disease. Essman W, editor. Vol. 5. Spectrum Press; NY-London: 1979. pp. 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dilman VM, Anisimov VN. Effect of treatment with phenformin, diphenylhydantoin or L-dopa on life span and tumour incidence in C3H/Sn mice. Gerontology. 1980;26:241–6. doi: 10.1159/000212423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Martin-Castillo B, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Menendez JA. Metformin and cancer: doses, mechanisms and the dandelion and hormetic phenomena. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1057–64. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.6.10994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Barzilai N, Ferrucci L. Insulin Resistance and Aging: A Cause or a Protective Response? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012 Aug 2; doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls145. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gori AM, Sofi F, Corsi AM, Gazzini A, Sestini I, et al. Predictors of vitamin B6 and folate concentrations in older persons: the In CHIANTI study. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1318–24. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.066217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Selhub J, Troen A, Rosenberg IH. B vitamins and the aging brain. Nutr Rev. 2010;68(Suppl 2):S112–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Spencer M, Jain A, Matteini A, Beamer B, Wang N-Y, et al. Serum levels of the immune activation marker neopterin change with age and gender and are modified by race, BMI, and percentage of body fat. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:858–865. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Niinisalo P, Raitala A, Pertovaara M, Oja SS, Lehtimäki T, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity associates with cardiovascular risk factors: the Health 2000 study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2008;68:767–770. doi: 10.1080/00365510802245685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fuchs D, Avanzas P, Arroyo-Espliguero R, Jenny M, Consuegra-Sanchez L, Kaski JC. The role of neopterin in atherogenesis and cardiovascular risk assessment. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:4644–4653. doi: 10.2174/092986709789878247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dilman VM. Development, aging and disease: A new rationale for an intervention strategy. Harvard Acad Publ. Chur; Switzerland: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vieira-Potter VJ, Strissel KJ, Xie C, Chang E, Bennett G, et al. Adipose tissue inflammation and reduced insulin sensitivity in ovariectomized mice occurs in the absence of increased adiposity. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4266–77. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Deguchi K, Kamada M, Irahara M, Maegawa M, Yamamoto S, et al. 0 Postmenopausal changes in production of type 1 and type 2 cytokines and the effects of hormone replacement therapy. Menopause. 2001;8:266–73. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zoghby SM, Abdel-Tawab GA, Girgis LH, Moursi GE, Zeitoun R, et al. Functional capacity of the tryptophan-niacin pathway in the premenarchial phase and in the menopausal age. Am J Clin Nutr. 1975;28:4–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/28.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schröcksnadel K, Widner B, Bergant A, Neurauter G, Schröcksnadel H, Fuchs D. Tryptophan degradation during and after gestation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;527:77–83. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0135-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kohl C, Walch T, Huber R, Kemmler G, Neurauter G, et al. Measurement of tryptophan, kynurenine and neopterin in women with and without postpartum blues. J Affect Disord. 2005;86:135–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bennink HJ, Schreurs WH. Improvement of oral glucose tolerance in gestational diabetes by pyridoxine. Br Med J. 1975;3:13–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5974.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cady SG, Sono M. 1-Methyl-DL-tryptophan, beta-(3-benzofuranyl)-DL-alanine (the oxygen analog of tryptophan), and beta-[3-benzo(b)thienyl]-DL-alanine (the sulfur analog of tryptophan) are competitive inhibitors for indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;291:326–333. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ryu JK, Choi HB, McLarnon JG. Combined minocycline plus pyruvate treatment enhances effects of each agent to inhibit inflammation, oxidative damage, and neuronal loss in an excitotoxic animal model of Huntington’s disease. Neuroscience. 2006;141:1835–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.O’Connor JC, Lawson MA, André C, Moreau M, Lestage J, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activation in mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:511–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Brustolim D, Ribeiro-dos-Santos R, Kast RE, Altshuler EL, et al. A new chapter opens in anti-inflammatory treatments: the antidepressant bupropion lowers production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:903–90. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Branconnier R, Cole JO, Oxenkrug GF. Cardiovascular effects of imipramine and bupropion and aged depressive patients. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1983;19:658–662. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yu CJ, Zheng MF, Kuang CX, Huang WD, Yang Q. Oren-gedoku-to and its constituents with therapeutic potential in Alzheimer’s disease inhibit indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase activity in vitro. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:257–266. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Li GS, Liu XH, Zhu H, Huang L, Liu YL, Ma CM, Qin C. Berberine-improved visceral white adipose tissue insulin resistance associated with altered sterol regulatory element-binding proteins, liver x receptors, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors transcriptional programs in diabetic hamsters. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34:644–654. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhao HL, Sui Y, Qiao CF, Yip KY, Leung RK, et al. Sustained antidiabetic effects of a berberine-containing Chinese herbal medicine through regulation of hepatic gene expression. Diabetes. 2012;61:933–43. doi: 10.2337/db11-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Di Pierro F, Villanova N, Agostini F, Marzocchi R, Soverini V, et al. Pilot study on the additive effects of berberine and oral type 2 diabetes agents for patients with suboptimal glycemic control. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2012;5:213–7. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S33718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Navrotskaya VV, Oxenkrug G, Vorobyova LI, Summergrad P. Berberine prolongs life span and stimulates locomotor activity of Drosophila melanogaster. Amer J Plant Sci. 2012;3:1037–1040. doi: 10.4236/ajps.2012.327123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Oxenkrug G, Navrotskaya V, Vorobyova L, Summergrad P. Minocycline Effect on Life and Health Span of Drosophila Melanogaster. Aging and Disease. 2012;3:352–359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nachum-Biala Y, Troen AM. B-vitamins for neuroprotection: narrowing the evidence gap. Biofactors. 2012;38:145–50. doi: 10.1002/biof.1006. Epub 2012 Mar 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Unoki-Kubota H, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Bujo H, Saito Y. Pyridoxamine dose-dependently decreased fasting insulin levels and improved insulin sensitivity in KK-A(y) mice, a model animal of obese, type 2 diabetes. Protein Pept Lett. 2010;17:1177–81. doi: 10.2174/092986610791760423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]