Abstract

We performed a focused review of risk of harms of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors in adult rheumatic diseases. Increased risk of serious infections, tuberculosis and other opportunistic infections has been reported across various studies, with etanercept appearing to have modestly better safety profile in terms of tuberculosis and opportunistic infections and infliximab with higher risk of serious infections. Evidence suggests no increase in risk of cancer with anti-TNF biologics, but there is an increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancer. Elderly patients appear to be at increased risk of incident or worsening heart failure with anti-TNF biologic use.

Keywords: Biologics, TNF-inhibitors, TNF biologics, harms, adverse effects, rheumatic diseases, Rheumatoid arthritis

Background/Introduction

The availability of anti-TNF biologics has revolutionized the management of rheumatic diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis (RA), now realistically aimed at achieving remission/ low disease activity states in patients with chronic disabling arthritides. The availability of effective therapeutic options has enabled rheumatologists to aggressively pursue the goals of disease control in a multi-faceted approach. This includes starting aggressive treatment early in the course of inflammatory arthritides, tailoring therapies to disease response that slows radiographic damage to joints and minimizes structural joint damage and disability and provides better symptom control and quality of life to patients and switching therapy when the response is not adequate [1, 2].

In the last decade, millions of patients with rheumatic diseases have been exposed to anti-TNF biologics, allowing us to retrospectively reflect on their efficacy and safety. Long-term safety data are also becoming available, mainly as open label extension studies of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), but also from rheumatic disease registries across the world. The low numbers of adverse events associated with anti-TNF biologic use make them challenging to study. Some have suggested that anti-TNF biologics have a favorable safety profile in the long-term [3]. Long-term adherence to therapies for chronic rheumatic conditions is challenging, since many patients quit for a variety of reasons, including lack of efficacy, adverse effects, patient preferences, socio-economic factors and/or challenges with health care access. Adverse effects or lack of efficacy are the most common reasons for stopping the use of anti-TNF biologics [4].

Patients and physicians are interested in defining the role of these medications in the treatment algorithm of rheumatic conditions [5]. Information of harms provided by randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is limited because of insufficient power to detect safety signals, especially given their rare occurrence. Moreover, the limited follow-up duration limits assessment of long-term safety outcomes. Caution ought to be exercised when extrapolating results from RCT population (healthier in general) to real-world patients, who often have a higher co-morbidity load than the trial populations. Additionally, while there are no significant barriers to medication availability and use in RCT, in the real world patients have preferences regarding treatment options related to out of pocket costs, route of administration and to their perceptions and individualized concerns about risk of specific medication-related adverse effects.

We anticipated that harms/ adverse effects of anti-TNF biologics would be uncommon or rare, and therefore made an a priori decision to include multiple rheumatic conditions, including RA. In this review article, we have summarized available evidence regarding the harms of anti-TNF biologics used for the treatment for adult rheumatic diseases. We also assessed the time-dependent risk of infections and explored differences of risk of harms between various anti-TNF biologic agents. We focused on the following harms/adverse effects:

Infections including serious infections, peri-operative infections and opportunistic infections (OIs) focusing on tuberculosis (TB) and fungal infections;

Cancer including solid cancers, skin cancers, lymphoma and leukemia;

Cardiac adverse effects including congestive heart failure (CHF); and

Hepatitis

Methods

Search strategy

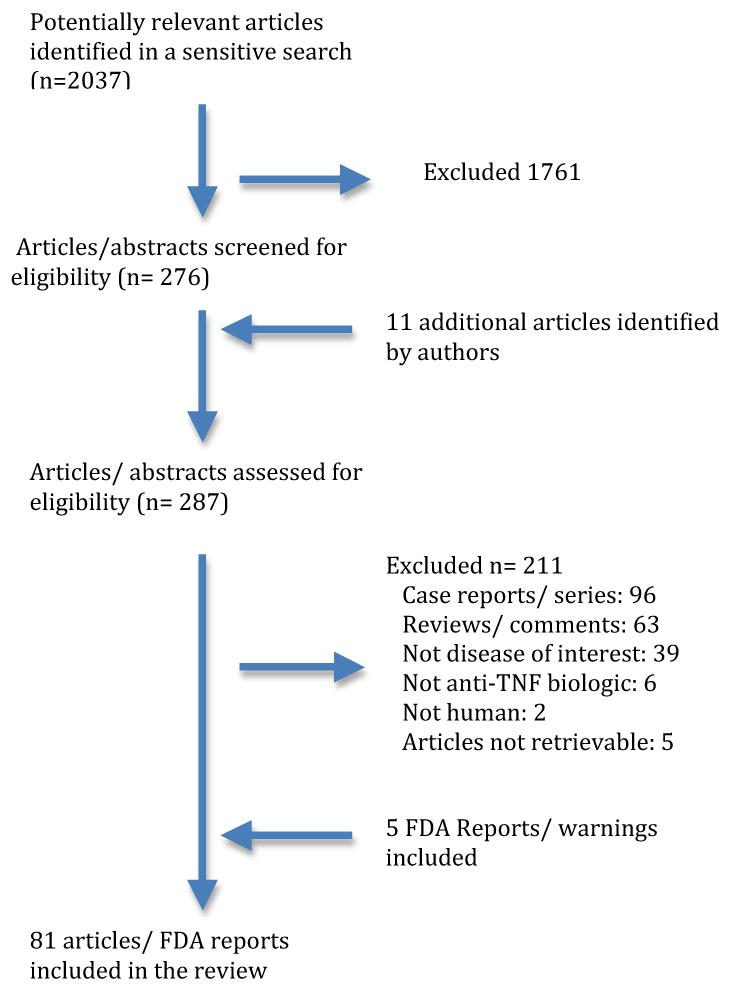

A sensitive search strategy was used to identify articles in MEDLINE up to November 2011 that included anti-TNF biologics for use in any adult rheumatic disease and reported on one or more adverse effects of interest, namely, infection, cancer, heart disease and hepatitis. The articles were limited to human studies and English language only. We retrieved 2,037 English language citations. The search was further refined by an experienced librarian using the following limits: infection, neoplasm, heart diseases and hepatitis; 276 articles were assessed for eligibility by reviewers (AJ, JAS) (Figure 1). We identified eleven additional articles.. Discrepancies in selection of articles were resolved by discussion. Since there were no outstanding disagreements after discussion, an adjudicator was not needed for the final decision of article inclusion/exclusion. Of these 287 articles, 211 articles were excluded for the following reasons: Case reports/ case series (n =96), reviews/ commentaries (n=63), not diseases of interest (n=39), not anti-TNF biologic drugs (n=6), not human (n=2) and articles not retrievable after being requested through interlibrary loan (n=5). Details of the search strategy are summarized in figure 1. In addition to this search, we searched the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website and found 5 publications detailing FDA warnings regarding adverse effects of anti-TNF agents. The lead author (AJ) abstracted data and the senior author (JAS) checked data from a random sample of studies; discrepancies were documented and resolved by consensus. Due to <5% error rate, our a prior cut-off for duplicate data abstraction, the lead author abstracted all data.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process for this review

Role of the funding agency

We did not obtain any funding to perform this review of the published literature. The senior author’s research time if protected by multiple research grants from federal agencies (JAS), none of whom played a role in developing the study protocol, conducting the systematic review and preparation and submission of the manuscript.

Results

In the various sections below, we describe the adverse effects data related to anti-TNF biologics with regards to infections (A), malignancy (B), congestive heart failure (C) and hepatitis (D).

A. RISK OF INFECTIONS

A1. SERIOUS INFECTIONS (also see Table 1)

Table 1. Serious infections, data from observational studies.

| No. of patients (TNF/ Comparator) |

Baseline disease characteristics |

Definition of infections |

At Risk Period | Duration of follow up |

Biologic Arm | Comparator Arm | Reported incidence |

Difference b/n anti-TNF agents |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baeten et ala 2003[1] |

SpA 107 |

NA | Hospitalized infections |

Not defined | 191.5 pt yrs |

Infliximab | None | Incidence 4.2/100 pt yrs |

NA |

| DREAM Kievit et al 2011 [2] |

RA 1560 |

Duration: 5.5-6.2 yrs HAQ: 1.3-1.4 DAS 5.0-5.2 |

US FDA Definition of SAEsb |

Not defined | 5 yrs | Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

None | Incidence 2.6/100 pt yrs |

Not studied |

| Flendrie 2003c [3] |

RA 230 | Duration: 11.6 yrs DAS: 6.1 |

NA | 12 months from start of therapy |

NA | Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

None | 12 cases of serious infections leading to drug discontinuation |

NA |

| Kiely 2003 [4] | Open label study of 20 RA patients receiving infliximab and leflunomide |

NA | Not defined | While on drug | 32 weeks | NA | NA | 6 episodes of infections: 4 requiring antibiotics; 1 death |

NA |

| Burmester 2009j [5] Long term safety study of 36 trials of adalimumab (RCTs, OLTs, LTEs) |

6 Rheumatic diseases (RA, PsA, AS, CD, Psoriasis, JIA) 19041 patients |

NA | NA | 1st dose of drug to 70 days after last dose |

10 yrs | Adalimumab | None | Events/ 100 patient yrs RA 4.65 PsA 2.81 AS 1.11 JIA 2.76 PsO 1.32 CD 5.18 |

NA |

| RABBIT Listing 2005 [6] |

RA 858/601 |

Duration: 9,8 yrs vs. 6 yrs DAS: 6.1vs 6.0 vs. 5.4 |

E2A Harmonization guidelinesb |

12 months from start of therapy, irrespective to further changes in therapy after the index dose |

12 months | Etanercept Infliximab |

Non Biologic DMARDs |

Incidence /100 pt yrs: 6.4, 6.2 vs. 2.3 (p 0.0016) RR (CI) 2.16 (0.9-5.4), 2.13 (0.8-5.5) respectively |

No |

| BSRBRd Dixon 2006 [7] |

RA 7664/1354 |

Duration: 12 vs. 6 yrs HAQ: 2.1 vs. 1.5 DAS: 6.6+/−1.0 vs. 5.1+/−1.4 |

Confirmed Infections leading to hospitalization/ death |

“Receiving treatment”: defined as 1st missed dose |

Median: 1.26 yrs/ 0.94 yrs |

Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

Non Biologic DMARDs |

IRR 1.03 (95% CI, 0.68-1.57) |

No |

| BSRBR Dixon 2007 [8] |

RA 8659/2170 |

Duration: 12 vs. 7 yrs HAQ: 2.1 vs 1.5 DAS: 6.6 vs. 5.0 |

As detailed above |

1st 90 days of treatment |

NA | Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

Non biologic DMARDs |

IRR (CI) 4.6 (1.8-11.9) |

IRR (CI) Eta 4.1 (1.5- 10.8) Inf 5.6 (2.1- 15.1) Ada 3.9 (1.3- 11.2) |

| TennCare Databasee Grijalva 2010 [9] |

RA 14586 pts/ >20000 drug episodes |

NA | Pneumonia or any infection requiring hospitalization |

Start of new medication+180 days |

180 days | Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

Non biologic DMARDs, steroids |

HR for hospitalized infection (CI); MTX referent 1.31 (0.78-2.19) |

NA |

| SABER project Grijalva 2011 [10] |

RA 10484, IBD 2323, Psoriasis and SpA 3215 |

NA | Hospitalized infections |

Start of medication to discontinuation or discontinued enrollment or serious infections or 12 months of follow up |

Duration of study 1998-2007 |

Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

Non biologic DMARDs |

HR (CI) RA: 1.05 (0.91- 1.21) IBD: 1.10 (0.83- 1.46) Psoriasis and SpA: 1.05 (0.76- 1.45) |

Infliximab HR (CI) vs. Etanercept 1.26 (1.07-1.47) vs. adalimumab 1.23 (1.02-1.48) |

| Genovese 2009f [11] |

185 pts received biologies after withdrawing from rituximab RA clinical trial programme (153 received anti TNF agent) |

Duration: 11.9 yrs DAS: 7.0 |

Met the regulatory criteria for SAEs or required IV abx |

Median: 11 months after receiving the medication |

Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

None | Rate of serious infection/ 100 patient yrs (CI) Before TNF inhibitor 6.63 (3.57- 12.32) After TNF inhibitor 4.93 (2.46-9.85) |

Not studied | |

| BSRBR Galloway 2011g [12] |

RA 11881/3673 |

1. Median: 11 yrs vs. 6 yrs 2. Mean: 2.0 vs. 1.5 3. Mean: 6.6 vs. 5.1 |

“Serious” septic Arthritis : requiring IV antibiotic, hospitalization or death |

While on anti- TNF therapy or within 90 days of 1st missed dose |

Duration of study: 2001-2009 |

Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

Non Biologic DMARDs |

HR (CI) 2.3 (1.2- 4.4) |

Eta 2.5 (1.3-4.9) Inf 2.4 (1.0-5.8) Ada 1.9 (0.9- 4.0) |

| U.S. Administrative database Curtis 2007 [13] |

RA 2393/2933 |

NA | Specific case definitions developed by investigators, who reviewed medical records |

“Ever-exposed”: ≥1 dose of TNF agent/ ≥3 doses of MTX 1st 6 months of treatment |

Median: 17 months |

Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

MTX | HR (CI),1.9 (1.3- 2.8) HR (CI),1.9 (1.3-2.8) |

Not studied |

| U.S. Administrative database Curtis 2007h [14] |

RA 2272/2933 |

NA | Same as above | New users of anti-TNF agent, current use |

NA | Etanercept, Infliximab |

MTX | IRR (CI) < 6 mo therapy Infliximab 2.4 (1.23-4.68) Etanercept 1.61 (0.75-3.47) > 6 mo therapy |

At < 6 mo, infliximab had higher risk of serious infections as compared to etanercept Infliximab 1.14 (0.55-2.24) Etanercept 1.37 (0.74-2.53) |

| Galloway 2011 (BSRBR) [15] |

RA 11798/3598 | Duration: 11 yrs vs. 6 yrs HAQ: 2.0 vs. 1.5 DAS: 6.6 vs. 5.1 |

Infections requiring IV Abx or leading to hospitalization or death |

While on anti- TNF therapy or within 90 days 1st missed dose |

Median: 3.9 yrs vs. 2.6 yrs |

Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

Non biologic DMARDs |

HR (CI) Overall: 1.2 (1.1- 1-5 1st 6 months: 1.8 (1.3-2.6) By age: < 55 yrs: 1.2 (0.8-1.6) 55-64 yrs: 1.4 (1.1-1.9) 65-74 yrs: 0.9 (0.7-1.2) > 75 yrs: 1.5 (0.9-2.6) |

No |

| U.S. Veterans [16] |

RA 1465/11772/13367 |

NA | Hospitalized infections |

While on medication+ 5 half lives or 1 dosing interval + 1 half life whichever was longer |

Study Duration: Oct 1998- Sep 2005 |

Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

Gp 1: HCQ, SSZ, Gold, Penicillamine Gp 2: MTX, Leflunomide, Azathioprine, Cyclophosphamide, Cyclosporine, Anakinra |

HR (CI) Anti-TNF biologic vs. Gp 1: 1.24 (1.02- 1.5) Gp 2 vs. Gp 1: 1.08 (0.95-1.24) |

HR (CI) Infliximab vs. Etanercept 1.51 (1.14-2.00) Adalimumab vs. Etanercept 0.95 (0.68-1.33) |

| Askling 2007 [17] |

RA 4167/10295 | NA | Hospitalized infections |

While on therapy |

Study duration: Jan 1999- Dec 2003 |

Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

Non-biologic DMARDs |

RR (CI) 1st Anti-TNF 1st yr: 1.43 (1.18-1.73) 2nd yr: 1.15 (0.87-1.50) After 2 yrs: 0.82 (0.62-1.50) 2nd Anti-TNF: 2.10 (1.36-3.27) |

|

| Kroesen 2003 [18] |

RA 60 | NA | Infections requiring IV Antibiotics or hospitalization |

While on therapy |

Anti-TNF therapy: 1999- 2002, Control: 2 yrs prior to anti-TNF initiation |

Etanercept, Infliximab Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

Non-biologic DMARDs Non-biologic DMARDs |

Incidence/ treatment yr Anti-TNF therapy arm: 0.181/ yr Control arm: 0.008/yr (p value NA) |

Anti-TNF arm: 11/60.65 treatment yrs Control arm: 1/ 123 treatment yrs |

| Salliot 2007 [19] |

Rheumatic diseases(> 95% RA, SpA) 623 pts |

Duration: 12.1 yrs |

Life threatening infections, requiring hospitalization or sequelae |

While on therapy |

Mean 1.3 yrs vs. 1.1 yrs |

Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

Non-biologic DMARDs |

Incidence/100 patient yrs Anti-TNF biologic arm: 10.5 +/−86.9 Control (prior to anti-TNF initiation): 3.4+/− 38.7/100 patient yrs P=0.03, NNH 14 |

|

| Neven 2005 [20] |

168 RA patients treated w/ infliximab |

Duration: 10 yrs | Infections requiring hospitalization or IV antibiotics |

NA | Study duration: Apr 2000- Oct 2002 |

Infliximab (Low dose: 3 mg/kg: n=132) (High dose: 3-7.5 mg/kg: n=36) |

None | 0.07 events/ patient/ yr in both groups |

NA |

| U.S. Administrative Database Curtis 2011 [21] |

RA 4916/2931 | NA | Hospitalized infections |

Current usage+ 90 days |

Median: 7.7 months |

Biologic Free (no biologic use in last yr) |

Biologic switchers | Incidence rate/ 100 person-yrs Biologic Free: 4.6 Switchers: 7.0 |

Etanercept 0.64 (0.49-0.84) and adalimumab HR (CI) 0.52 (0.39-0.71)had lower risk of infection vs. infliximab |

| Bernatsky 2010 [22] 7 observational studies |

RA 1,24357 subjects |

NA | Serious infections, primarily hospitalized infections. Excluded clinical trials |

While on drug (duration of trial) |

0.4-6.3 yrs | Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

Placebo or non biologic DMARD |

RR (CI) 1.37 (1.18-1.6) |

Not studied |

|

Case control

studies | |||||||||

| Bernatsky 2007 [23] |

23733 RA patients on DMARDS: 261 (1.1%) were on anti-TNF agents |

NA | Hospitalized infections |

Prescription within 45 days prior to index date |

6.3 yrs | Cases (hospitalized infections) |

Controls (no hospitalized infections) |

RR (CI) in TNF users: 1.93 (0.70-5.34) |

NA |

2 cases of TB reactivation

US FDA definition of SAE: events disabling daily activities persistently or significantly, needing hospitalization or being life threatening, E2A Harmonization guidelines: events that are life threatening, require hospitalization, congenital anomalies or result in disability or death

2 cases of TB reactivation

Increased risk of serious skin and soft tissue infections IRR 4.28 (1.06-17.17)

HR for pneumonia (CI), MTX referent 1.61 (0.85-3.03)

88.6% patients had peripheral B cell depletion at the time of biologic initiation

No difference in risk of prosthetic joint septic arthritis in 2 groups

Adalimumab excluded due to small numbers

Risk of serious infections decreased significantly as trial duration increased

Rates of infection for early RA 2.76/100 pt yrs, established RA 4.91/ 100 pt yrs

Observational Data: Studies reporting incidence rates only

Five studies provided incidence rates for serious infections. In a cohort of 107 patients with spondyloarthropathy treated with infliximab [6], 8 hospitalized infections were observed during 191 patient years of follow up. During 5,017 years of follow up of patients in the Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis register, the incidence rate of serious infections was 2.6/100 patient years [7]. In another Dutch single center study of 230 RA patients started on anti-TNF biologics, 12 cases of discontinuation due to serious infections were reported [8]. In an open label study of 20 patients with RA on infliximab and leflunomide combination therapy, one case of serious infection was reported during the 32-week follow-up [9]. In a long-term safety study of adalimumab evaluating 36 trials across various inflammatory diseases including mainly rheumatic diseases, rates of serious infections were reported as 1.11-5.18/ 100 patient years [10]. Highest rates were observed in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease [10].

Observational Data: Studies reporting no increase in serious infection risk

A prospective cohort study from German biologics register RABBIT (German acronym for Rheumatoid Arthritis--Observation of Biologic Therapy) reported a non-significant trend towards 2-fold increased risk of serious infections in RA patients treated with anti-TNF biologic agents [etanercept (RR = = 2.16; 95% CI 0.9 to 5.4) or infliximab (RR = 2.13; 95% CI 0.8 to 5.5)] as compared to non-biologic DMARDs; however, authors noted that the study was not powered to detect increased risk of serious infections [11].

Similarly, no increase in risk of serious infections (OR = 1.03, 95% CI, 0.68 to1.57) was reported in anti-TNF biologic users as compared to non-biologic DMARD users in a prospective observational study of severe RA patients from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register (BSRBR) [12]. However, the investigators observed a 4-fold increased risk of frequency of serious skin and soft tissue infections (OR = 4.28, 95% CI, 1.06 to 17.17) [12]. There was no differential infection risk between the 3 anti-TNF biologics. No significant differences were observed using different definitions of at risk period for exposure to RA medications (receiving treatment, receiving treatment + 90 days or ever treated)[12]. In an extension study by the same group [13], similar results with no significant increase in risk of serious infections was noted in the anti-TNF biologic group for the duration of treatment compared to non-biologic DMARD cohort. However, a nearly 5-fold increased risk of serious infection was observed (OR = 4.6, 95% CI, 1.8 to 11.9) in the first 90 days after initiation of treatment in the anti-TNF biologic cohort as compared to non-biologic DMARD cohort[13].

Initiation of anti-TNF biologics was not associated with increased risk of hospitalization for serious infections in U.S. Medicaid database as compared to MTX (HR = 1.31, 95% CI 0.78 to 2.19) [14]. Similar results were observed for risk of serious infections with anti-TNF biologics in a large retrospective cohort study of U.S. patients with autoimmune diseases, including RA (HR = 1.05, 95% CI 0.91-1.21), psoriasis and spondyloarthritis (HR = 1.05, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.45) as compared to non-biologic DMARDs [15]. In the subgroup of patients with RA, infliximab (HR = 1.25, 95% CI 1.07 to 1.48), but not adalimumab or etanercept, was associated with higher risk of serious infections as compared to non-biologic DMARDs [15]. In a long-term safety study of patients who received a second biologic agent (majority comprised of anti-TNF biologics) after withdrawing from rituximab RA clinical trial program [16], there was no increase in the rate of serious infections despite persistent B cell depletion at the time of initiation of second biologic in nearly 90% of patients.

In a study of a large Canadian administrative database of RA patients on various DMARDs (1.1% were on anti-TNF biologics), using a nested case control design, anti-TNF biologic use was not associated with increased risk of hospitalized infections; however the number of infection episodes in patients on anti-TNF biologic agents was very small (n=5) [17].

Observational Data: Studies reporting increased risk of serious infections

In contrast, increased rates of hospitalization with infections have been reported in RA patients treated with anti-TNF biologics (HR = 1.9, 95% CI 1.3 to 2.8) in a retrospective cohort study of patients enrolled in a large US health care plan as compared to MTX [18]. In another retrospective cohort study of U.S. veterans with RA, anti-TNF biologic therapy was associated with increased risk of hospitalized infections as compared to select non-biologic DMARDs (HR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.5) [19]. Similarly increased risk of hospitalized infections was reported in the anti-TNF biologic group as compared to non-biologic DMARDs in the first two years of therapy in a prospective cohort study of Swedish Biologics Register ARTIS (Anti Rheumatic Therapies In Sweden) [20]. In a single center study, the incidence of serious infections was higher in RA patients while on anti-TNF therapy (0.181/treatment year) as compared to the two years prior to anti-TNF initiation (0.008/treatment year) [21, 22]. Similarly, increased risk of serious infection with anti-TNF therapy as compared to the period just prior to anti-TNF initiation was reported in another single center study of patients with rheumatic diseases [21, 22].

Site-specific Infections

Studies have reported data on risk of site-specific infections with anti-TNF biologic use. As mentioned previously, one such prospective observational study of BSRBR reported a 4-fold increased risk of serious skin and soft tissue infections [12]. In another prospective observational study of the same cohort, a 2-fold higher risk of septic arthritis was reported in anti-TNF biologic users as compared to non-biologic DMARD users [23].

Meta-analyses

Meta-analyses reporting no increase in Risk

In a systematic meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of 3 anti-TNF biologics (etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab) in patients with RA with trial duration ranging from 6-24 months [24], no significant increase in risk of serious infections was seen with anti-TNF biologics (OR =1.4, 95% CI 0.8-2.2). However, high doses of infliximab were associated with increased risk of serious infection (p =0.006).

In another systematic meta-analysis of safety data of 18 RCTs of 3 anti-TNF biologics (etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab) in patients with RA with trial duration ranging from 3-18 months [25], treatment with recommended doses of anti-TNF biologics did not increase the odds of serious infections (OR = 1.21; 95% CI 0.89-1.63). In the subset of patients receiving higher than recommended doses of adalimumab and infliximab (no clinical trials evaluated higher doses of etanercept), the unadjusted analysis identified an increased risk of serious infection with higher doses of adalimumab and infliximab (OR = 2.07; 95% CI 1.31-3.26), however, analysis adjusted for exposure did not find significant results (RR = 1.99; 95% CI 0.90-4.37). Risk of serious infection was noted to decrease significantly as the trial duration increased (p =0.035).

In a meta-analysis of 20 RCTs of 5 anti-TNF biologics used for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) with trial duration ranging from 12-30 wks, no increase in risk of serious infections was observed in anti-TNF biologic group (OR = 0.7; 95% CI 0.4-1.21) [26].

Similarly, no increased risk of serious infections was observed with anti-TNF biologics when compared to methotrexate in a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs of DMARD-naïve early RA patients with trial duration at least 6 months (OR = 1.28; 95% CI 0.8-2.0) [27].

Meta-analyses reporting increased serious infection risk

In a large meta-analysis of 160 RCTs (median duration, 6 months) and 46 extension studies (median duration 13 months) of 9 biologics (5 anti-TNF agents plus anakinra, tocilizumab, abatacept and rituximab) used for any indication other than HIV, no significant difference in risk of serious infections with each of the four of the five anti-TNF biologics (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab) at standard doses compared to placebo or non-biologic DMARD controls [28]. Certolizumab pegol (OR = 4.75, 95% CI 1.52-18.45) was associated with higher risk of serious infections compared to placebo or non-biologic DMARDs. Anti-TNF biologics as a class (all five medications, etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol and golimumab; OR = 1.37, 95% CI 1.04-1.82) and TNF receptor antibody as a class (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol and golimumab; OR = 1.48, 95% CI 1.13-1.75) were each associated with an increased risk of serious infections as compared to placebo or non-biologic DMARDs. There was no significance difference in serious infection risk between anti-TNF biologics [28].

In a meta-analysis of 9 randomized controlled trials of anti-TNF antibodies, namely, infliximab and adalimumab in patients with RA with trial duration ranging from 3-12 months [29], the pooled odds ratio for serious infections in the anti-TNF biologic group as compared to placebo or non-biologic DMARD controls was reported to be 2.0 (95% CI 1.3-3.1). No statistically significant differences in serious infection risk were observed in high dose vs. low dose anti-TNF biologic groups.

In a meta-analysis of 7 observational studies of anti-TNF biologic use in RA, higher risk of serious infections (RR = 1.37; 95% CI 1.18-1.6) was observed with anti-TNF biologic use compared to placebo or non-biologic DMARD controls [30].

Time dependent Infection Risk

As noted by Dixon et al. above, [13] the increased risk of serious infections tends to highest early in the course of initiation of anti-TNF biologic agents, as the incidence risk ratio (IRR) of 4.6 in the first 90 days (CI 1.8-11.9) in the BSRBR cohort[16]. Another study from BSRBR reported more modest increased risk of serious infections in the 1st 6 months of therapy (HR = 1.8; 95% CI 1.3-2.6) that disappeared after the 1st 6-months of therapy [31]. Using 90 days of anti-TNF biologic initiation as the cut-point [13] as opposed to 1st 6 months [31] in the BSRBR, data suggests that risk of serious infections is highest in the 1st 90 days of anti-TNF biologic initiation. Using in a US health plan data, Curtis et al. reported an increased risk of serious infections in patients with RA on infliximab (IRR = 2.4, 95% CI 1.23-4.68) as compared to MTX in the first 6 months of initiation of therapy (but not etanercept IRR = 1.61, 95% CI 0.75-3.47) that disappeared after the first 6 months of use [32]. More modest risk of serious infections with anti-TNF biologics have been reported in the Swedish Biologics Register (ARTIS) [20] with 1.2-1.5 fold increased risk in the first 2 years of initiation of anti-TNF biologic therapy that disappeared after the first 2 years of therapy.

Differential risk of serious infection between anti-TNF biologics

In a study of US administrative claims data, in the 1st 6 months of initiation of therapy, infliximab (IRR 2.40, 95% CI 1.23-4.68) was associated with increased risk of serious infections in patients with RA as compared to MTX, while no significant increase in risk of serious infections was observed with etanercept (IRR 1.61, 95% CI 0.75-3.47) [32]. In another study of a large US health care database of patients with RA on biologic therapies, compared with infliximab, the risk of serious infections was lower with adalimumab (HR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.39-0.71) and etanercept (HR = 0.64, 95% CI 0.49-0.84).. Furthermore, the differential increased risk of serious infections observed with infliximab was much higher in patients who were at high infection risk at baseline (based on infection risk score, derived and validated by the study investigators) [33]. In a large retrospective US cohort study of approximately 20,000 patients with various autoimmune diseases, among the new users of anti-TNF therapies in the subgroup of RA patients, an increased risk of serious infections was noted with infliximab compared with etanercept (HR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.07-1.47) and adalimumab (HR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.02-1.48). The data were compiled from four U.S. automated pharmacy databases of Medicaid/Medicare patients, pharmaceutical assistance databases and a managed care consortium (Kaiser Permanente), hence inclusive of underserved, vulnerable patients [15, 32]. Similar results in a retrospective cohort study of U.S. veterans with a high differential risk of hospitalized infections were reported with infliximab (HR = 1.51, 95% CI 1.14 to 2.00), but not with adalimumab (HR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.68-1.33) as compared to etanercept [19].

No difference in rates of serious infections was reported in the low dose infliximab (3mg/kg) vs. high dose infliximab (3-7.5 mg/kg) group in a prospective cohort study of RA patients treated with infliximab [34].

Several plausible mechanisms such as different pharmacokinetics, binding properties, mechanisms of action and administration modes have been proposed to explain the differences in risks associated with anti-TNF biologics.

New Biologic users versus Biologic switchers

In a recent retrospective administrative database cohort study using a large U.S. healthcare organization that followed RA patients over a median follow up of 7.7 months [33], the mean rate of hospitalized infections in biologic switchers (66% on anti-TNF biologics) was higher (7.0/100 patient years) as compared to patients starting their first new biologic (90% on anti-TNF biologics) at 4.6/100 patient years (p<0.0001). In both biologic-free and biologic switcher sub-groups, risk of hospitalized infections was lower with other biologics (etanercept, adalimumab, abatacept and rituximab) as compared to infliximab. In addition, biologic switchers were more likely to have comorbidities, like COPD and diabetes, to use narcotics and prednisone and to use higher doses of prednisone, compared to new biologic users. Increased risk of hospitalized infections has also been reported with 2nd anti-TNF biologic use as compared to 1st anti-TNF biologic use (RR = 2.10; 95% CI 1.36-3.27) in a prospective cohort study of the Swedish Biologic Register (ARTIS) [20].

Elderly patients

Using data from a large U.S health plan [35], elderly patients with RA had no increase in serious bacterial infections in anti-TNF biologic group as compared to MTX (RR = 1.0; 95% CI 0.60-1.67). In a pooled safety analysis of etanercept clinical trials, there was no increase in incidence of serious infections in the elderly group as compared to younger population [36]. Similarly, in a prospective observational study from the BSRBR, no significant increased risk of serious infections was observed in the subgroup of elderly patients taking anti-TNF biologics compared to non-biologic DMARDs (age < 55 HR = 1.2, 95% CI 0.8-1.6; age > 75;HR = 1.5, 95% CI 0.9-2.6) [31].

Summary of Warnings from the FDA and other regulatory agencies related to Serious Infections with anti-TNF biologics

Serious and sometimes fatal infections due to bacterial, mycobacterial, viral, invasive fungal or other opportunistic infections have been reported with anti-TNF biologic use. The risks and benefits should be considered prior to initiating anti-TNF biologic therapy in patients with chronic or recurrent infections and patients at increased risk of infections (e.g. poorly controlled diabetes). Anti-TNF biologic therapy should not be initiated in the presence of active infection [37-41]. Recently, FDA issued an update that Legionella and Listeria infections can lead to potentially fatal outcomes in patients on anti-TNF biologics [39]. Similarly, 214 cases of serious infections related to 2 anti-TNF biologics (etanercept, infliximab) were reported to Health Canadafrom 2001-2004, prompting guidelines for physicians similar to the FDA warnings as noted above [42].

A2. TUBERCULOSIS (TB) REACTIVATION and OPPORTUNISTIC INFECTIONS (OIs) (also see Table 2)

Table 2. Serious infections, data from meta-analyses and Pooled RCT data.

| No. of patients (TNF/ Comparator) |

Baseline disease characteristics |

Definition of infections |

At Risk Period | Duration of follow up |

Biologic Arm | Comparator Arm |

Reported incidence |

Difference b/n anti-TNF agents |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alonso-Ruiz et al [24] 13 RCTs |

RA (7087 pts in TNF + comparator gps) |

NA | NA | While on drug (duration of trial) |

6-24 months |

Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

Placebo or Non Biologic DMARD |

OR (CI): 1.4 (0.8- 2.2) |

High doses of Infliximab associated with increased risk of serious infection p =0.006 |

| Leombruno 2009i 18 RCTs [25] |

RA 8808 subjects |

NA | NA | While on drug (duration of trial) |

3-18 months |

Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab at recommended doses |

Placebo or Non Biologic DMARD |

OR (CI) 1.21(0.89-1.63), Exposure adjusted RR (CI) 1.07 (0.81-1.43) |

OR of infections with ETA was lower, however significance unknown |

| While on drug (duration of trial) |

3-18 months |

Infliximab Adalimumab at high doses |

Placebo or Non Biologic DMARD |

OR (CI) 2.07(1.31- 3.26), Exposure adjusted RR (CI) 1.99 (0.90-4.37) |

|||||

| Dommasch 2011 20 RCTs [26] |

Psoriasis, PsA 6810 patients |

NA | NA | Duration of trial | 12-30 wks |

Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab Golimumab Certolizumab |

Placebo or non biologic DMARD |

OR (CI) 0.7 (0.4-1.21) |

NA |

| Thompson 2011 [27] 6 RCTs |

2183/1236 | Duration < 3 yrs HAQ 1.3-1.6 DAS data NA for 5/6 trials |

Hospitalized infections |

While on drug (duration of trial) |

At least 6 months |

Adalimumab or Etanercept or Golimumab or Certolizumab or Infliximab |

Non biologic DMARDs |

OR (CI) 1.28 (0.8-2.0) |

NA |

| Bongartz 2006 [28] 9 RCTs |

RA 5014 patients in TNF + comparator gp |

NA, described as heterogeneous in terms of disease duration and disease activity |

NA | While on drug (duration of trial) |

3-12 months |

Adalimumab, Infliximab |

Placebo or Non biologic DMARDs |

Pooled OR (CI) 2.0 (1.3-3.1) |

Similar results were observed b/n high dose and low dose TNF groups |

| Singh 2011 [29] 160 RCTs and 46 extension studies |

Any indication other than HIV: 60630 subjects |

NA | Infections leading to death, hospitalization or disability. Included bacterial infections and OIs in most studies |

While on drug (duration of study) |

RCTs: Median 6 months Ltes: 13 months |

5 Anti-TNF agents, Abatacept, Anakinra, Rituximab, Tocilizumab |

Placebo or Non Biologic DMARD |

All anti-TNF OR (CI) 1.41 (1.13-1.75) TNF Antibody 1.48 (1.15-1.90) TNF Receptor 1.17 (0.74-1.83) Eta 1.29 (0.72- 2.45) Inf 1.41 (0.75-2.62) Ada 1.23 (0.65- 2.4) |

Ada vs. Eta 0.78 (0.58-1.16) Inf vs. Eta 0.93 (0.6-1.42) Inf vs. Ada 1.19 (0.79-1.79) |

| Fleishmann 2006 [30] Pooled data from 22 Etanercept RCTs |

< 65 yrs: 3296 ≥ 65 yrs: 597 |

NA | Medically important infections: IV antibiotics or admission to hospital |

At least 1 dose of etanercept |

< 65: 5895 patient yrs, ≥ 65: 903 patient yrs |

Etanercept, age < 65 |

Etanercept, age ≥ 65 |

Medically important infections No significant difference b/n 2 gps |

In addition to serious bacterial infections, TB and other opportunistic infections have been reported in patients receiving anti-TNF biologic agents. TNF plays a crucial role in the host response to intracellular pathogens like mycobacterium tuberculosis. TNF stimulates recruitment of inflammatory cells to the site of infection, stimulates the formation and maintenance of granuloma formation, activates macrophages that engulf and kill mycobacteria. Differences in pharmacokinetics of the anti-TNF biologics may confer a differential risk of reactivation of TB with infliximab (binds both soluble and transmembrane TNF with high avidity and has a longer half-life (10.5 days)) as compared to etanercept (binds only to soluble TNF and has a relatively short half-life of 3 days) [43].

In an observational study using BIOBADASER (Spanish for Spanish Registry of Adverse Events of Biological Therapies in Rheumatoid Arthritis), approximately half of patients on biologic therapy were appropriately screened for TB after the TB screening guidelines were issued [44]. Failure to screen according to recommendations was associated with a 7-fold higher risk of developing TB [44].

Observational studies: Studies reporting incidence rates of TB and OIs only

In a long term safety study of adalimumab evaluating 36 trials across various rheumatic diseases, the range for rates of TB, OIs and histoplasmosis were reported at 0-0.30, 0-0.09, 0-0.03 events/ 100 patient years [10].

Observational studies: Increased risk of TB reactivation

Pharmacovigilance studies have suggested that anti-TNF biologic therapy increases the risk of TB reactivation [45, 46]. In a recent prospective observational study of the British register BSRBR, 40 cases of TB in anti-TNF biologic treated RA patients (118 cases/ 100,000 patient years), versus no TB cases in RA non-biologic DMARD cohort were reported [47]. More than 60% of TB cases were extrapulmonary. Nearly half of the disseminated TB cases in patients in adalimumab group occurred after anti-TNF biologic therapy had been discontinued [47]. In addition, within the anti-TNF biologic cohort, monoclonal antibodies (infliximab/ adalimumab) were associated with 3-4 fold higher risk of TB as compared to etanercept [47]. Whether sequential anti-TNF biologic use ensues a disproportionately higher risk of TB remains unanswered.

In a study from Swedish Biologics Register ARTIS, anti-TNF biologics were associated with 4-fold higher risk of TB as compared to non-biologic DMARDs and most cases of TB were pulmonary [48]. A higher risk was observed with infliximab when compared to etanercept.

Meta-analysis: Increased risk of TB reactivation

In a recent meta-analysis of 160 RCTs and 46 extension studies of 9 biologics (including anti-TNF agents) used for various indications, nearly 5-fold increased risk of reactivation of TB was noted with anti-TNF biologic use (OR = 4.68, 95% CI 1.18-18.60) as compared to control treatment [28].

Observational studies: Increased risk of other Opportunistic Infections (OIs)

In an incidence study, data from French RATIO (Research Axed on Tolerance of Biotherapies) registry reported 45 OIs (bacterial, viral, fungal or parasitic, excluding TB) with 57,711 patient years of anti-TNF biologic use (151.6/100,000 patient years) (approximately 25% ICU admissions with 10% mortality) [49]. The difference from the general population, however, failed to reach statistical significance due to very wide confidence interval (95% CI 0.0-468.3). In the case control analysis from the above registry data, infliximab and adalimumab were associated with a 10-17 fold higher risk of OIs as compared to etanercept [49]. In 2 of the 38 patients, anti–TNF biologic therapy had been stopped more than 4 months prior to the OIs [49]. Similarly, using data collected through Adverse Effects Reporting System (AERS) of the US FDA, association between anti-TNF biologic use and granulomatous infections was noted, the risk being 3-fold higher for infliximab as compared to etanercept [50].

In a study of 281 published case reports of invasive fungal infections in patients using anti-TNF biologic therapy in PubMed and MEDLINE, majority (80%) were in infliximab users; histoplasma (30%), candida (23%) and aspergillus (23%) were the most frequently reported organisms [51]. Majority of patients had RA or other arthritides and 98% were on at least one other immunosuppressive medication, usually glucocorticoid.

Observational Studies: No increase in risk of other Opportunistic Infections

In a prospective cohort study of RA patients, anti-TNF biologic use was associated with increased risk of overall infections, however the risk of opportunistic infections failed to reached statistical significance [52].

Observational studies: Increased risk of Herpes Zoster

In a prospective observational study of German biologics register RABBIT, significantly increased risk for herpes zoster was found in patients treated with anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies (infliximab, adalimumab, HR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.13-3.00) as compared to non biologic DMARDs [53], however neither etanercept alone nor anti-TNF biologic treatment as a class were associated with higher risk. In a retrospective analysis of BIOBADASER, a 10-fold higher risk of hospitalization secondary to varicella infections was reported in patients exposed to anti-TNF agents when compared to general Spanish population [54]. In another retrospective study of U.S. veterans with RA, patients receiving medications to treat mild RA (hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, gold, penicillamine) had a lower incidence of herpes zoster (8/1000 patient years) as compared to patients receiving medications used to treat moderate RA (MTX, leflunomide, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine and anakinra: 11.18/ 1000 patient years) or severe RA (anti-TNF biologics: 10.6/1000 patient years) [55]. Etanercept (HR = 0.62, 95% CI 0.4-0.95) and adalimumab (HR = 0.53, 95% CI 0.31-0.91) were associated with lower risk of herpes zoster as compared to infliximab [55].

Summary of FDA Warnings

FDA has issued warning that cases of TB (frequently disseminated or extra-pulmonary disease), disseminated invasive fungal infections (histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis, candidiasis, aspergillus, blastomycosis and pneumocystis) and other OIs have been reported with the use of anti-TNF biologic agents[37-41]. TB reactivation has been reported in approximately 0.01% of patients in global clinical studies, incidence is likely higher in endemic areas. Patients should be screened for latent TB prior to and during treatment with anti-TNF biologic agents. Treatment for latent TB infection should be initiated prior to anti-TNF biologic therapy. Patients should be monitored closely for development of TB during and after treatment with ant-TNF biologic agents. Currently, there are no screening guidelines for opportunistic infections before initiation of anti-TNF biologic agents. Empiric anti-fungal treatment of at risk patients who develop severe systemic illness should be considered.

FDA AERS reported 25 TB cases associated with etanercept use for treatment of rheumatic diseases from 1998-2002 with an estimated rate of TB at 10/100,000 years of exposure [56]. Approximately 50% (13) patients had extra-pulmonary TB.

12 cases of TB and 16 cases of serious fungal infections related to anti-TNF biologic use (etanercept and infliximab) were reported to Health Canada from 2001-2004 [42]

A3. PERI-OPERATIVE/PROSTHETIC INFECTIONS (also see Table 3)

Table 3. Tuberculosis (TB) and Opportunistic infections, data from observational and pharmacovigilance studies and meta-analyses.

| No. of patients (TNF/ Comparator) |

Baseline disease characteristics |

Definition of infections |

At Risk Period |

Duration of follow up |

Biologic Arm | Comparator Arm | Reported Incidence | Difference b/n anti-TNF agents |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Observational studies

| |||||||||

|

TB

| |||||||||

| BSRBR Dixon 2010[31] |

RA 10712/ 3232 |

Duration: 11 yrs vs. 6 yrs HAQ:2.0 (0.6) vs. 1.5 (0.8) DAS: 6.6 (1.0) vs. 5.1(1.3) |

Physician reported, 60% were "verified" |

Ever on Drug |

3.2 yrs vs. 2.3 yrs |

Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

Non biologic DMARDs |

40 TB casesa in anti- TNF cohort, none in DMARD cohort -Rate 118/ 100000 pt yrs |

IRR (CI) with ETA as referent INF: 2.2 (0.9-5.8) ADA: 4.2 (1.8-9.9) |

| Askling 2005[32] |

RA Anti-TNF 2500/ Inpatient RA cohort 31,185/ Early RA cohort 2430 |

HAQ: 1.5 / −/ 0.8 DAS: 5.8/-/3.6 |

Hospitalized infections, ICD codes |

Ever on drug |

Duration of study 1999- 2004 |

Etanercept Infliximab |

Non biologic DMARDs |

15 TB casesb in anti- TNF cohort RR (CI) Vs. Inpatient Register: 4.0 (1.3-12) Vs. Early arthritis: 4.1 (0.8-21) |

RR (CI) ETA vs. INF 0.5 (0.1-2.4) |

| BIOBADASER Gomez-Reino 2007 [33] |

Rheumatic diseases 5198 |

NA | + Culture for M TB |

Ever on drug |

03/2002- 01/2006 |

Latent TB Infection (LTBI) guidelines not followed Etanercept, Adalimumab, Infliximab |

LTBI guidelines followed Etanercept, Adalimumab, Infliximab |

IRR (CI) 7.01 (1.6-64.7) |

No difference in 3 anti- TNF agents |

|

| |||||||||

|

OIs

| |||||||||

| Salmon-Ceron et al[34] |

Various autoimmune diseases 57711 patient yrs of TNF use |

Duration: 9.5 yrs |

Physician confirmed |

Current or prior TNF use Median time of OI from start of therapy: 16.2 yrs |

Duration of study 2004- 2007 |

Etanercept, Adalimumab, Infliximab |

General French population in Incidence study, Etanercept, Adalimumab, Infliximab in Case control study |

45 cases of OI 15 bacterial, 18 severe viral, 10 fungal, 2 parasitic 26% ICU admission rate, 9% mortality Rate of OI/100000 pt yrs: 151.6 |

Adalimumab vs. ETA 0R (CI) 10 (2.3-44.4) infliximab vs. ETA 17.6 (4.3-72.9) |

| CORRONA Greenberg et al 2010 [35] |

RA 4659/1274 |

Duration: 11.41(9.6) yrs vs. 10.1 (9.8) yrs HAQ: 0.4 (0.4) vs. 0.3 (0.4) |

Physician reported |

Current use of medication |

1.4 yrs | Etanercept, Infliximab, adalimumab |

Non MTX, non biologic DMARDs |

IRR Overall infection (CI) 1.52 (1.30-1.78) IRR opportunisticc infection (CI) 1.67 (0.95-2.94) |

NA |

|

| |||||||||

|

Herpes zoster/ Varicella Zoster Virus

| |||||||||

| RABBIT Strangefeld 2009 [36] |

RA 3266/ 1774 |

Duration: 9 yrs vs. 6 yrs DAS: 5.8 (1.3) vs. 5.0 (1.3) |

Reported by rheumatologist or Patient reports confirmed by medical records |

Current use of medication |

5 yrs | Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

Non biologic DMARDs |

HR (CI) Anti TNF as a class: 1.63 (0.97-2.74) Etanercept: 1.36 (0.73-2.55) Ada/ Inf: 1.82 (1.05- 3.15) |

Higher incidence of multidermatomal and ophthalmic zoster:2.5% in TNF gp, w/ most cases reported in antibody gp vs. 0.9% in control gpd |

| BIOBADASER Garcia Dovel et al 2010 [37] |

Various autoimmune diseases 4655 patients on TNF agents |

NA | Hospitalized infection w/ VZV (Chicken pox/ shingles) as reported to BIOBADASER |

Current use of medication |

8 yrs | Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

General Spanish population |

SIR (CI) for hospitalization due to shingles 9 (3-20) SIR (CI) for hospitalization due to chickenpox 19(5-47) |

NA |

| McDonald et al 2009 [38] |

RA 20357 | NA | ICD 9 codes for HZ in a clinical encounter |

Current use of medication |

71607 patient yrs |

Severe RA (Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab) |

Mild RA (HCQ, SSZ, Gold, penicillamine) Mod RA (MTX, Leflunomide, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, anakinra |

Incidence rate: Anti-TNF biologic gp: 10.6/1000 patient yrs Mild RA 8/1000 patient yrs (p< 0.01) Mod RA 11.18/1000 patient yrs (NS vs. severe RAA) |

Hazard vs.. Infliximab HR (CI) Etanercept 0.62 (0.4- 0.95) Adalimumab 0.53 (0.31- 0.91) |

|

| |||||||||

|

Pharmacovigilance Reports

| |||||||||

| Wallis 2004 [39] |

NA | NA | As reported to FDA AERS Database |

NA | NA | Etanercept, Infliximab |

None | Granulomatous infections/ 100,000 pts: Etanercept: 74 Infliximab: 239 |

Infliximab with 3 fold risk of granulomatous infections (vs. etanercept), highest increase in risk with infliximab in the 1st 3 months of treatmente |

| Keane 2001[40] |

NA | NA | Reported to FDA Medwatch |

NA | NA | Infliximab | None | Rate of TB/100,000 pts: 24.4f |

NA |

| Tsiodras et al 2008[41] |

NA | NA | Case reports in MEDLINE/ PubMed |

NA | NA | Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

None | Cases of invasive fungal infections Infliximab 226 Etanercept 44 Adalimumab 11g |

|

|

| |||||||||

|

Meta-

analyses | |||||||||

| Singh 2011 [29] 160 RCTs and 46 extension studies |

Any indication other than HIV: 60630 subjects |

NA | NA | While on drug (duration of study) |

RCTs: Median 6 months Ltes: 13 months |

5 Anti-TNF agents, Abatacept, Anakinra, Rituximab, Tocilizumab |

Placebo or Non Biologic DMARD |

OR (CI) of TB reactivation in biologic arm vs. placebo 4.68 (1.18- 18.60)h |

NA |

| Burmester 2009 [5] 36 trials (RCTs, OLTs, LTEs) |

6 Rheumatic diseases 19041 patients |

NA | NA | 1st dose of drug to 70 days after last dose |

10 yrs | Adalimumab | None | Event rate/100 pt yrs TB 0-0.30 OI 0-0.09 Histo 0-0.03 |

NA |

62% cases were extrapulmonary

33% had extrapulmonary TB

Most frequent OI: Varicella (82 cases) zoster, other common OIs: Pneumocystis jeroveci, TB

Other factors associated with increased risk of HZ: Age HR 1.28, CI 1.05-1.55, Glucocorticoids, > 10 mg/ day 2.52 (1.12-5.65)

Most common infection: M TB, 2nd MC: Histoplasmosis*Rate of infections calculating using manufacturer reports of approx. no. of patients treated with anti-TNF agent

Rate of infections calculating using manufacturer reports of approx. no. of patients treated with anti-TNF agent 70% of cases of TB developed after 3 or fewer infusions of infliximab. Approx. 60% cases had extrapulmonary disease

Most common IFI s were histoplasmosis (30%), candidiasis (23%), aspergillosis (23%)

Included bacterial infections and OIs in most studies

Observational Studies: Increased risk

Increased risk of surgical site infections (SSI), (majority were superficial infections) was observed with infliximab and etanercept as compared to non-biologic DMARDs in a single center, retrospective case control study (OR = 21.8, p=0.036) [57]. Anti-TNF biologics were withheld for 2-4 weeks in the perioperative period. Arthritis flares were noted in anti-TNF biologic group as well, with nearly all cases observed in etanercept group (short half life). In a small case control study of patient on anti-TNF biologics, steroid use and joint infection within the past year were identified as risk factors for joint arthroplasty infection in perioperative period [58].

Observational studies: no increased risk

A prospective observational study of the BSRBR, reported 2-fold higher risk of septic arthritis in anti-TNF biologic users as compared to non-biologic DMARD users (HR = 2.3, 95% CI 1.2-4.4) [23]. History of prior large joint replacement was a risk factor for septic arthritis irrespective of whether the septic arthritis developed in a prosthetic joint (HR = 2.45, 95% CI 1.9-3.17). In the subset of patients with prosthetic joint septic arthritis (approximately 25%,majority in 90-day post-op period), there was no difference in post-operative infection rates in anti-TNF biologic group versus non-biologic DMARD group (OR = 0.8,; 95% CI 0.2-3.5) [23]. No increased risk of SSI has been reported in anti-TNF biologic users who continued anti-TNF biologic use peri-operatively vs. patients who discontinued anti-TNF biologic agent in the peri-operative period [59].

B. CANCER RISK (also see Table 4)

Table 4. Peri-operative infections, data from three observational studies.

| No. of patients (TNF/ Comparator) |

Baseline disease characteristics (Disease duration, HAQ or DAS scores) |

Definition of infections |

At Risk Period | Duration of follow up |

Biologic Arm | Comparator Arm |

Reported Incidence | Difference b/n anti-TNF agents |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kawakami et al 2010 [42] Case control study |

RA, with joint arthroplasties 64/64 |

Duration: 10.6 yrs vs. 13.4 yrs |

Per CDC guidelines * |

Undefined | NA | Infliximab Etanercept |

Non biologic DMARDs |

SSI: 12.5% vs. 2% . OR 21.8 (p = 0.016) |

“Flares” (Arthralgias ) reported in TNF gp only: INF vs. ETA: 2 vs. 9; p=0.02 |

| Den Broeder 2007 [43]a |

RA 196/1023 |

Duration: 16- 17 yrs vs. 17 yrs |

CDC criteria and/ or antibiotic use |

Perioperative | 1 yr | Etanercept, Adalimumab, Infliximab |

Non biologic DMARDs |

Infection rates: No TNF use 4.0% peri-op TNF use, discontinuation :5.8% TNF use, continuation peri-op: 8.7% Continuation vs.. Discontinuation: Infection OR (CI) 1.5 (0.43-5.2) |

NA |

| RATIO Gilson et al 2010 [44]b Case control study |

Rheumatic diseases pts treated w/ TNF inhibitors and joint arthroplasties with and without SSI N=20/40 |

Duration: 20.4 yrs vs. 20.3 yrs |

Reported by physicians and validated by investigators, 19/20 had microbial data |

On TNF or < 1 yr since TNF withdrawal |

At least for the duration of antibiotic therapy, up to 1 yr in some cases |

Etanercept, Adalimumab, Infliximab |

Etanercept, Adalimumab, Infliximab |

Risk factor for TJA infection: steroid intake OR (CI): 5.0 (1.1 21.6) per 5 mg/day increase, Previously infected joint within the past yr: OR (CI): 88.3 (1.1 7071) |

NA |

CDC guidelines for SSI: diagnosis of superficial or deep incisional SSI by operators and IV or oral antibiotics in all such cases

Risk factors for SSI: Elbow surgery OR (CI) : 4.1 (1.6-10.1), foot/ ankle surgery 3.2 (1.6-6.5), prior skin or wound infection 13.8 (5.2-36.7); decreased risk: Duration of surgery 0.42 (0.23-0.78); SSZ use: 0.21 (0.05-0.89)

MSSA was the most common organism, no OIs observed, however numbers small

Patients with prior malignancy are usually excluded from RCTs of anti-TNF biologics. Hence, only observational registry data are available to address the influence of anti-TNF biologic therapy on cancer rates in patients with prior cancer.

B1. ALL CANCERS

Observational Data: Studies reporting incidence rates only

During 5,017 years of follow up of patients in Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis register, the incidence rate of malignancies was 0.6/100 patient years of exposure to anti-TNF biologics [7]. In another Dutch single center study of 230 RA patients treated with anti-TNF biologics, 2 cases of malignancies were reported at 12 month follow up [8].

Observational data: No increased cancer risk

In a prospective cohort study from the Swedish biologics cohort ARTIS, no increase in overall risk of solid cancers [60], except non-melanoma skin cancer (where a 2-3 fold increased risk) was noted in the anti-TNF biologic group as compared to non-biologic DMARD comparator cohorts.

Using survey reports, no increase in overall risk of malignancy was observed in Turkish patients treated with anti TNF biologics for various rheumatologic disorders, when compared to general population [61]. Although the number of events was small, etanercept was associated with increased risk of malignancy (SIR 2.3, 95% CI 1.1-4.23) compared to general population [61]. A long-term safety study of RCTs, OLTs and LTEs of adalimumab with 10 year follow up reported no increased risk of cancer overall with adalimumab therapy as compared to general population [10].

Observational data: No increased cancer risk in patients with prior malignancy

In an analysis of incident malignancy in patients with prior malignancy using the data from BSRBR, no increased risk of incident malignancy was observed with anti-TNF biologics as compared to non-biologic DMARDs (IRR = 0.58; 95% CI 0.23-1.43). However, higher rates of prior cancers observed in the comparator cohort suggest that most patients with recurrent cancers as well as recent cancers may not have been considered for treatment with anti-TNF biologics [62].

Meta-analyses: No increased cancer risk

A meta-analysis of 74 RCTs of rheumatic diseases of median duration < 6 months reported no increase in short-term all cancer risk (< 1/3rd events adjudicated) except NMSC with anti-TNF biologics as compared to non-biologic DMARDs [63]. A systematic meta-analyses of 18 RCTs of RA patients with trial duration of 3-18 months provided evidence of no increase in risk of malignancy with anti-TNF biologic use as compared to controls; irrespective of biologic dose and specific cancer sub-types (lymphomas, non cutaneous cancers and melanoma and non melanoma skin cancers) [25]. Overall, the number of events was small at 34 (0.8%) in anti-TNF biologic group vs. 15 (0.6%) in control group) [25]. Similar results were reported in 2 other meta-analyses of RCTs of RA patients with trial duration of at least 6 months treated with anti-TNF biologic therapies, with no increase in risk of malignancy overall [24, 27], regardless of the dosing of anti-TNF biologics [24]. Similarly, no increase in risk of overall cancers, non-melanoma skin cancers or all cancers except non-melanoma skin cancers was observed in the anti-TNF biologic group as compared to controls in a meta-analysis of 20 RCTs analyzing 5 anti-TNF agents in patients with psoriasis or PsA with trial duration of 12-30 wks [26].

Meta-analyses: Increased cancer risk

In a systematic meta-analysis of 9 RCTs (trial duration ranging from 3-12 months) of 2 anti-TNF antibodies (infliximab and adalimumab) in RA, increased risk of malignancies (except NMSC) in patients treated with the infliximab or adalimumab vs. placebo was observed (OR = 3.3; 95% CI 1.2-9.1) [29]. The observation of increased risk was attributed to high dose anti-TNF biologic therapy vs placebo: OR = 4.3 (CI 1.6-11.8); vs. low dose anti-TNF biologic therapy OR = 3.4 (CI 1.4-8.2)while the low dose anti-TNF therapy did not seem to pose high risk of malignancy (vs. placebo: OR = 1.4;CI 0.3-5.7) [29]. There were some methodological issues with reporting of malignancies in this meta-analysis (exclusion of cancers diagnosed in the 1st 6 wks of trials and inclusion of cases that occurred after the trials were no longer underway). Nevertheless, the number of events was small at 24 (0.8%) in the anti-TNF biologic group vs. 2 (0.2%) in the controls).

B2. LYMPHOMA

Recent data indicates strong correlation between autoimmunity and lymphoma risk. In a meta-analysis of 20 cohort studies (heterogeneity: P< 0.01;I2> 70%) of patients with various autoimmune diseases, increased risk of Non Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) was observed (systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): SIR 7.4; 95% CI3.3-17.0, RA: SIR 3.9; 95% CI 2.5-5.9 and scleroderma: SIR 18.8;CI 9.5-37.3) as compared to general population [64, 65]. In a large case control study of approximately 3000 patients with NHL, risk of NHL was increased in association with various autoimmune diseases (RA: OR = 1.5; 95% CI 1.1-1.9, scleroderma: OR = 6.1; 95% CI 1.4-27, SLE 4.6; 95% CI 1.0-22, celiac disease: OR = 2.1; 95% CI 1.0-4.8) [64, 65]. Additionally, concerns regarding risk of NHL development with anti-TNF biologic treatment have been raised. Assuming that anti-TNF biologics are typically prescribed to patients with severe rheumatic diseases, the increased numbers of lymphomas observed in anti-TNF biologic treated patients may be indicative of the subset of patients with rheumatic diseases who have high predisposition of NHL development at baseline as a result of the underlying active inflammation and the underlying condition, as opposed to the treatment itself.

Observational Data: Increased lymphoma risk

A prospective case control analysis of RATIO registry revealed increased risk of lymphoma in patients receiving anti-TNF biologic therapy when compared to general French population (SIR 2.4; 95% CI 1.7-3.2) [66]. A higher risk of lymphoma with infliximab (SIR 4.1, 95% CI 2.3-7.1) and adalimumab (SIR 3.6 95% CI 2.3-5.6) was observed as compared to etanercept (SIR 0.9 95% 0.4-1.8)[66]. Similar results with 2-3 fold increased risk of lymphoma with anti-TNF biologic therapy have been reported in RA patients enrolled in Swedish Biologic Register ARTIS[67, 68] NDB (National Databank) [69, 70] as well as a long-term safety study of adalimumab in patients with various rheumatic diseases [10] when compared to the general population. No difference in lymphoma risk has been observed between anti-TNF biologic versus non-biologic DMARD group [65, 66, 67, 68].

Data from Italian RA LORHEN (Lombardi Rheumatoid Arthritis Network) registry reports an even higher risk of lymphoma in RA patients treated with anti-TNF biologics as compared to general population (SIR = 5.99; 95% CI 1.61-15.35) [71]. In the SSATG (South Swedish Arthritis Treatment Group) cohort, 11-fold increased risk of lymphoma was observed in the anti-TNF biologic group as compared to the general population (SIR = 11.5; 95% CI 3.7-26.9). These results need to be interpreted with caution, given that the observed number of lymphomas was small (5 cases in anti-TNF biologic group). Additionally, there was a non significant trend towards 5-fold increased risk between the anti-TNF biologic and non biologic DMARDs (RR = 4.9; 95% CI 0.9-26.2), however the rate of lymphoma in the non-biologic DMARD group was unexpectedly low (SIR = 1.3; 95% CI 0.2-4.5) as compared to general population [72].

Meta-analysis: No increased risk of lymphoma

In a recent large meta-analysis of 160 RCTs of biologics, including anti-TNF agents, no increase in risk of lymphoma was observed with biologic therapy overall (OR = 0.53, 95% CI 0.17-1.66) as compared to controls. Similar results with no increase in lymphoma risk was observed with the 4 anti-TNF biologics (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol), compared to controls; the risk of lymphoma with golimumab was not estimable [28].

B3. LEUKEMIA

Very few cases of leukemia have been noted in an observational study as well as a meta-analysis [28, 63] analyzing malignancy risk of anti-TNF biologics. No detailed analyses/comparisons were provided for leukemia in these studies for us to summarize in this focused review.

In a study that examined safety data from international pharmacovigilance program of World Health Organization, 121 cases of various types of leukemia were reported in patients using anti-TNF biologics [73]. The most common reasons for anti-TNF biologic use were RA and Crohn’s disease (numbers not provided). In majority of cases, only anti-TNF biologic therapy was recorded as the suspect drug, although approximately 50% of patients were using MTX or other immunosuppressive drugs concomitantly. Inherent to the nature of pharmacovigilance reporting, the data may be confounded to an unknown extent and no estimate of incidence rate is possible. Hence, further pharmacoepidemiological studies are needed to determine association, if any, between anti-TNF biologic therapy and leukemia [73].

Summary of Warnings from the FDA and other regulatory agencies

In the FDA report of patients treated with anti-TNF biologics, a 3-fold higher risk of lymphoma (0.09 cases per 100 patient-years) was observed as compared to general population. Cases of a rare, very aggressive and often fatal hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma (HSTCL) have been reported to FDA, primarily in adolescents and young adults being treated for inflammatory bowel disease with anti-TNF biologics (with concomitant or prior azathioprine and/or mercaptopurine use in nearly all cases). Of note, some of these cases have been reported in patients receiving azathioprine or mercaptopurine alone. Hence, it is unclear whether the occurrence of HSTCL is related to above mentioned therapies individually or combination of immunosuppressive therapy or underlying inflammatory disease alone. FDA has recommended monitoring for malignancies in patients treated with these agents. (http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm251443.htm) [38, 40, 41]. In an analysis of adverse events with infliximab (used for various indications including IBD) in FDA AERS database, signal for lymphoma was identified with a seven-fold increase in observed rate of lymphoma as compared to expected rate [74].

A study of nearly 150 case reports of lymphoma in patients treated with anti-TNF biologics (included published case reports (MEDLINE) and cases reported to national French pharmacovigilance database (National Commission of Pharmacovigilance centralizes at the Agence Françiase de Sécurité Sanitaire (AFSSAPS)), noted differences in the characteristics of reported cases in the published case report group (younger, more likely to be 1st anti-TNF biologic users, earlier onset of lymphoma (12 months vs. 30 months) as compared to the pharmacovigilance database. In addition, the most prevalent indication for anti-TNF biologic use was Crohn’s disease (particularly HSTCL) in the former group while RA was the most prevalent disease in the latter group. [75]. This study highlighted the inherent limitations of case reports as well as pharmacovigilance reports in the ascertainment of causality of adverse events.

C. CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE (CHF) AND CARDIAC ARRYTHMIA (also see Table 5) Observational Studies: Increased risk of CHF

Table 5. Malignancy, data from incidence and observational studies.

| No. of patients (TNF/ Comparator) |

Baseline disease characteristics |

Definition of malignancy |

At Risk Period |

Duration of follow up |

Biologic Arm | Comparator Arm | Reported Incidence | Difference b/n anti-TNF agents |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence studies | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

|

DREAM

Kievit et al 2011 [2] |

RA, 1560 |

Duration: 5.5 6 .2 y rs HAQ: 1.3-1.4 DAS 5.0-5.2 |

Patient reported | Not defined |

5 yrs | Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

None | Incidence 0.6/100 pt yrs |

Not studied |

| Flendrie 2003 [3] | RA, 230 | Duration: 11.6 yrs DAS: 6.1 |

NA | 12 months from start of therapy |

NA | Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

None | 2 cases of malignancy reported |

NA |

|

| |||||||||

|

Observational

studies |

|||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| ARTIS Askling 2005 [45] |

TNF/ Inpatient register/ Early RA 4160/ 53067/ 3703 |

HAQ: 1.4 vs. NA vs. 0.7 DAS: 5.6 vs. NA vs. 3.5 |

Swedish Cancer registry, solid cancers |

Ever received TNF |

Mean: 2.3 yrs, 5.6 yrs, 3.6 yrs respectively |

Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

Non biologic DMARDs |

Vs. gen population: TNF gp: SIR (CI) 0.9 (0.7-1.2) Inpatient RA: 1.05 (1.01-1.08) Early RA: 1.1 (0.9- 1.3 |

|

| Pay 2008 [46] | Rheumatic diseases 2199 patients on anti-TNF agents |

NA | Reported cases of malignancy in a survey of Turkish patients |

Ever received TNF |

Not applicable |

Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

General population, malignancy rates determined by a survey |

l3) 15 malignancy cases SIR (CI) 1.26 (0.7-2.08) |

SIR (CI) Etanercept 2.3 (1.1-4.23) |

| BSRBR Dixon 2010 [47] |

RA TNF, 10735 DMARD, 3235 |

Duration: 11 yrs vs. 9 yrs HAQ:2.2 (0.5) vs. 1.6 (0.7) DAS: 6.7 (1.2) vs. 5.0 (1.3) |

CIS and non- melanoma skin cancers were excluded. Prior malignancy: identified through linkage to UK cancer registers. Incident malignancies were validated and categorized as definite, probable or possible |

After 1st dose of TNF agent or after the registration date for DMARD cohort |

Median: 3.1 person- yrs in TNF cohort vs. 1.9 person -yrs in DMARD cohort |

Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

Non biologic DMARDs |

IRR (CI) for incident malignancy: 0.58 (0.23-1.43) Stratifying by time since prior malignancy did not reveal any significant differences in the risk of incident malignancya |

NA |

| RATIO Mariette 2010 [48] |

Rheumatic diseases 57711 patient yrs of anti-TNF treatment compared w/ general French population. |

In lymphoma cases: Duration: 11.0 yrs |

New cases of lymphoma alerted to pharmacovigilance centers or drug companies. In 36/38 cases with biopsies. All cases validated by committee of 3 lymphoma experts. |

Ever received TNF |

2 yrs | Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

General French population |

38 lymphoma cases Incidence Rate: 42.1/100 000 pt yrs SIR (CI) 2.4 (1.7-3.2) w/ French population as referent |

SIR Etanercept: 0.9 (p=0.72) Adalimumab: 4.1 (p<0.001) Infliximab: 3.6 p<0.001) Case control arm: OR (CI) Adalimumab vs. Etanercept: 4.7 (1.3-17.7) Infliximab vs. Etanercept 4.1 (1.4-12.5) |

| ARTIS Askling 2009 [49] |

RA 6604 patients in anti-TNF gp, 67743 national RA cohort, 471024 Gen population |

TNF cohort Duration: 10.6 yrs HAQ: 1.4 (0.6) DAS: 5.5 (1.3) |

Cases of lymphoma identified through Swedish Cancer Register (reporting mandatory by treating physician and pathologist) |

Ever received TNF |

9 yrs | Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

-Non-biologic DMARDs. -General population |

26 lymphoma cases RR (CI) -TNF gp vs. Non biologic DMARDgp 1.35 (0.82-2.11) - vs. general population 2.72 (1.82-4.08) |

No |

| ARTIS Askling 2005 [50] |

RA 4160 patients in anti-TNF gp Inpatient RA cohort: 53067 Early RA cohort 3703 |

HAQ: 1.4 vs. NAvs. 0.7 DAS: 5.6 vs. NAvs. 3.5 |

Cases of lymphoma identified through Swedish Cancer Register (pathology slides reviewed by investigators) |

Ever received TNF |

4 yrs | Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

-Inpatient RA register -Early RA cohort |

TNF cohort vs. Inpatient register cohort RR, 1.1 (CI, 0.6-2.1) Early RA cohort vs. Inpatient register cohort RR, 0.8 (CI, 0.4-1.4) TNF cohort vs. general population SIR, 2.9 (CI, 1.3- 5.5 |

|

| NDB Wolfe 2004 [51] |

RA Anti TNF: 9162 MTX 5593 No MTX, no biologic 4474 |

Duration: 13.7 yrs vs. 13.5 yrs vs. 13.5 yrs HAQ 1.2 (0.7) vs. 1.1 (0 .7) vs. 1.0 (0.7) |

Lymphoma: patient self-report followed by validation by contacting physician or medical records where possible. Based on level of evidence: classified as validated, refuted or likely lymphoma |

Ever received TNF |

2.5 yrs | Etanercept, infliximab | -MTX - No MTX, No biologic |

29 lymphoma cases no Compared to general population SIR (95% CI) All RA: 1.9 (1.3-2.7) TNF gp 2.9 (1.7- 4.9) MTX 1.7 (0.9-3.2) RA, no MTX, no anti-TNF: 1.0 (0.4- 2.5) |

No |

| NDB Wolfe 2007 [52]b |

19591 RA patients total; 10815 patients in anti TNF gp |

All participants: Duration: 14.1 yrs HAQ: Mean 1.1 (0.7) |

Lymphoma reported in patient questionnaires, validated by medical records |

Ever received TNF |

Mean 3.7 yrs |

-Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab -Anti-TNF+ MTX |

-Non anti-TNF DMARDs - - MTX alone |

Anti-TNF vs. non anti-TNF gp OR 1.0 (0.6-1.8) Anti-TNF + MTX vs. MTX alone gp OR 1.1 (0.6-2.0) |

|

| LORHEN Pallavicini 2010 [53] |

1064 RA patients treated w/ anti TNF agents |

Duration (n): < 5yrs=324 5-10 yrs 338 > 10 yrs 402 HAQ: 1.46 DAS: 5.90 |

NA | Ever received TNF |

2 3 months |

Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab |

General population data from Varese and Milan cancer report |

SIR (CI) Overall cancer: 0.94 (0.55-1.48) Solid cancers 0.72 (0.38-1.24) Hematologic cancers 4.08 (1.32- 9.53) Lymphomas 5.99 (1.61-15.35) |

|

| SSATG Geborek 2005 [54] |

RA 757/ 800 |

Duration: 12 yrs vs. 11 yrs HAQ Quartile > 3: 61% vs. 41% |

Swedish cancer registry. All tumors, lymphomas |

Ever received TNF |

Person years: TNF gp: 1603 Comparator gp: 3948 |

Etanercept Infliximab |

Non biologic DMARDs |

TNF group, 5 cases of lymphoma Comparator group, 2 lymphoma cases SIR (95% CI) Vs. general population -Total tumor risk: TNF gp 1.1 (0.6- 1.8) Comparison gp 1.4 (0.6-1.8) -Lymphoma risk: TNF gp 11.5 (3.7- 26.9) -Comparison gp 1.3 (0.2-4.5) |

|

|

| |||||||||

| Pharmacovigilance reports | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Theophile 2011 [55] | Rheumatic diseases 81/61 |

NA | Lymphoma confirmed by histopathological analysis |

Ever on TNF |

NA | Published case reports of lymphoma after Anti-TNF therapy |

Cases of lymphoma after anti-TNF therapy reported to French pharmacovigilance system |

In published case reports, pts were younger (p=0.03), more frequently on 1st TNF (p=0.03), and Crohn’s disease was the main indication of anti-TNF use ( p,0.0001) and in particular involved HSTCL. In pharmacovigilance reports, a succession of anti- TNFs (p=0.03) and adalimumab ( p< 0.0001) were more frequently reported ; RA was the main indication for anti- TNF use. |

|

| Meyboom 2008 [56] | Rheumatic diseases 121 |

NA | Leukemia cases reported to WHO pharmacovigilance program |

Ever on anti-TNF agent |

NA | Leukemia cases in patients on TNF blockers |

None | 121 cases of leukemia reported |

|

Subtypes of prior malignancies was balanced in the 2 cohorts, 80% being solid tumors. Prior malignancy: Rate: 1.6% in anti-TNF cohort vs. 3.6% in DMARD cohort

incidence rate in NDB cohort overall: 105.9/100000 yrs of exposure. SIR (CI) in NDB cohort vs. SEER 1.8 (1.5-2.2)

In a retrospective cohort study of elderly patients with RA, using data from a large US Health care plan, increased risk of hospitalization secondary to heart failure was observed in patients receiving anti-TNF biologics when compared to MTX users, regardless of prior history of heart failure [76]. In patients with prior history of heart failure, there was a four-fold increased risk of death among anti-TNF biologic users as compared to MTX users [76].

Observational Studies: No increased risk of CHF

A study of RA patients enrolled in NDB reported that anti-TNF biologic therapy was associated with lower risk of heart failure overall (2.8% vs. 3.9%, p=0.03) and similar of incident heart failure as compared to non-biologic DMARDs (0.2% in both groups, p=0.68) [77]. In the prospective German registry (RABBIT), no significant increased risk of incident heart failure or worsening of previous heart failure was noticed in anti-TNF biologic users as compared to non-biologic DMARD users when adjusted for RA disease activity [78].

Similarly, no increase in risk of incident or worsening of prevalent heart failure was reported in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis on anti-TNF biologics as compared to RA controls on non-biologic DMARDs as well as non-RA controls [79]. Using administrative claims data from a large U.S. healthcare organization; in patients with RA and Crohn’s disease; younger than 50 years, non- significant increase in risk of heart failure was observed in the anti-TNF biologic users as compared to non-biologic DMARD users. The number of cases of presumed heart failure was small (n=9), emphasizing the need for larger cohort in order to provide more precise estimation of risk of heart failure in the younger population exposed to anti-TNF biologic therapies [80].

Meta-analysis: No increased risk of CHF

In a recent large meta-analysis of RCTs and extension studies of biologics (including anti-TNF biologics) for various indications, there was no increase in risk of CHF (OR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.18-2.69) with biologic use [28].

Cardiac Arrhythmia

No increase in risk of arrhythmias during infliximab infusion was noted in a prospective, placebo controlled cross-over study of 75 patients with RA or SpA [81]. There was a trend toward increased risk of ventricular tachyarrythmias in the infliximab group (OR = 3.17, 95% CI 0.61-16.26) as compared to placebo that failed to reach statistical significance [81].

D. HEPATITIS

Majority of the available evidence for hepatitis associated with anti-TNF biologic use consisted of case reports or small case series of autoimmune hepatitis or reactivation of hepatitis B in conjunction with anti-TNF biologic use.

The 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of RA and the 2012 update [1, 2] contraindicate the use of biologic agents in all patients with acute hepatitis B or C and in both chronic hepatitis B and C with significant liver injury (Child-Pugh classes B or C). No clear consensus is available regarding hepatitis B or C patients with Child-Pugh class A.

In an analysis of spontaneously reported adverse effects to FDA in infliximab users, no signal was detected for relationship between infliximab and hepatitis [74].

Discussion and Conclusions

In this focused review, we focused on reviewing and summarizing data related to selected pre-specified serious harms of anti-TNF biologics in adult rheumatic diseases. Specifically, we reviewed the evidence related to serious infections including bacterial, fungal and opportunistic infections, tuberculosis reactivation, malignancy, congestive heart failure and hepatitis. We relied on data from observational studies, meta-analyses and pharmacovigilance reports regarding the harms of biologics in patients with rheumatic diseases.