Background: VEGF plays an important role in tumor growth and metastasis.

Results: KLF-4 suppresses VEGF expression in normal breast cells by recruiting HDACs. Cancer cells do not recruit HDACs due to low KLF-4 levels.

Conclusion: Loss of KLF-4-HDAC-mediated suppression and active recruitment of SAF-1 causes cancer cell-specific VEGF expression.

Significance: Findings identified a previously unknown mechanism of VEGF regulation and revealed new therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Breast Cancer, DNA-Protein Interaction, Gene Regulation, Transcription Factors

Abstract

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is recognized as an important angiogenic factor that promotes angiogenesis in a series of pathological conditions, including cancer, inflammation, and ischemic disorders. We have recently shown that the inflammatory transcription factor SAF-1 is, at least in part, responsible for the marked increase of VEGF levels in breast cancer. Here, we show that SAF-1-mediated induction of VEGF is repressed by KLF-4 transcription factor. KLF-4 is abundantly present in normal breast epithelial cells, but its level is considerably reduced in breast cancer cells and clinical cancer tissues. In the human VEGF promoter, SAF-1- and KLF-4-binding elements are overlapping, whereas SAF-1 induces and KLF-4 suppresses VEGF expression. Ectopic overexpression of KLF-4 and RNAi-mediated inhibition of endogenous KLF-4 supported the role of KLF-4 as a transcriptional repressor of VEGF and an inhibitor of angiogenesis in breast cancer cells. We show that KLF-4 recruits histone deacetylases (HDACs) -2 and -3 at the VEGF promoter. Chronological ChIP assays demonstrated the occupancy of KLF-4, HDAC2, and HDAC3 in the VEGF promoter in normal MCF-10A cells but not in MDA-MB-231 cancer cells. Co-transfection of KLF-4 and HDAC expression plasmids in breast cancer cells results in synergistic repression of VEGF expression and inhibition of angiogenic potential of these carcinoma cells. Together these results identify a new mechanism of VEGF up-regulation in cancer that involves concomitant loss of KLF-4-HDAC-mediated transcriptional repression and active recruitment of SAF-1-mediated transcriptional activation.

Introduction

Angiogenesis plays an important role in many pathological diseases, including tumor growth and metastasis, inflammation, and ischemic disease. In cancer, angiogenesis facilitates increased blood supply and thus allows influx of essential nutrients and growth factors as well as oxygen to the growing tumor (1). Distinct angiogenic patterns have been linked with high grade in situ ductal carcinoma of the breast, and poor breast cancer prognosis correlates with increasing microvascular density (2). Angiogenesis involves an orchestrated action of many bioactive molecules, among which vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays a critical role (3, 4). Role of VEGF in breast cancer is evident from the observation of increased synthesis of this growth factor in breast cancer cells (5, 6) as well as in breast cancer tissues (7). Consistent with these findings, VEGF polymorphism that leads to increased VEGF expression has been linked to an increased risk of invasive breast cancer (8).

Recently, we reported a novel mechanism in which inflammation-responsive serum amyloid A activating factor 1 (SAF-1)3 transcription factor was identified as a regulator of VEGF expression in triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma cells (9). Depletion of SAF-1 suppressed VEGF expression in MDA-MB-231 cells and reduced two hallmark features of angiogenesis, namely cell migration and endothelial cell tube formation (9). We also noted that forced expression of SAF-1 had a much lower impact on VEGF expression in normal breast epithelial cells as compared with that in breast cancer cells. These results suggested that normal breast epithelial cells may contain some specific factors, which act as a suppressor of SAF-1 and thereby could thwart SAF-1-mediated increase of VEGF in normal breast epithelial cells. This possibility also extended the notion that breast carcinoma cells may contain reduced levels of such potential repressor molecules.

To test this hypothesis, a comprehensive analysis was undertaken, and we report that Kruppel-like factor-4 (KLF-4) transcription factor acts as a transcriptional repressor of VEGF by competing with SAF-1 for binding to the human VEGF promoter. Furthermore, we show that KLF-4 recruits histone deacetylases (HDACs) at the VEGF promoter and synergistically represses VEGF expression. In correlation, KLF-4·HDAC complex was seen to be highly abundant in normal breast epithelial cells but at a considerably lower level in breast cancer cells and tissues. Incidentally, KLF-4 has been linked to several pathophysiological conditions, including cancer (10–12). Together, these studies reveal a new regulatory mechanism, in which interaction of KLF-4-HDACs controls and maintains the low VEGF expression level in normal breast epithelial cells, the loss of which and the activation of SAF-1, at least in part, leads to increased VEGF expression and angiogenesis in breast cancer.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines and Transfection Assay

MCF-10A, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, and HUVEC-CS human umbilical vein endothelial cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), cultured, and stored following ATCC protocol of authentication by short terminal repeat analysis. The cells were maintained in DMEM/high glucose medium supplemented with 7% FBS. For harvesting conditioned medium (CM), the cells were first grown in DMEM containing 7% FCS for 24 h. Next, the culture medium was replaced with DMEM containing 0.5% FCS, and the cells were grown for an additional 48 h, after which the medium was collected, centrifuged at 1,000 × g, and stored at −80 °C for further use.

Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) assay was performed following transfection of cells with reporter plasmid 1.2 VEGF-CAT or empty vector (pBLCAT3) as described (9). In each transfection assay, pSVβ-gal (Promega) DNA was added for normalization of transfection efficiency. For overexpression of candidate genes, pcDFLAG-SAF1, pcD-KLF-4, pcD-HDAC2, and pcD-HDAC3 were used for transfection of cells. In some transfection assays, KLF-4 siRNA, control siRNA, and MAZ/SAF-1 siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were added.

Immunohistochemistry of Tumor Tissue Microarrays and Western Immunoblot Analysis

Tissue microarrays containing archived, formalin-fixed, and paraffin-embedded specimens of 60 samples, 30 primary breast carcinoma and 30 normal adjacent tissues (diameter 2.0 mm; thickness, 4 μm), were purchased from IMGENEX Corp. Deparaffinized tissue sections were stained with antibodies, including KLF-4, 1:100 dilution (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), VEGF, 1:100 dilution (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and SAF-1, 1:500 dilution (9) by following the method as described (9). Antigen retrieval was done by heating deparaffinized tissues in sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0, for 30 min in a commercially available vegetable steamer. For all of the antibodies, the intensity of staining and a proportion of positive cells were determined by following the methods as described (13–15). A semiquantitative estimate of expression levels of the antigens, including KLF-4, SAF-1, and VEGF, was based on the combined score for the proportion of staining cells, and the intensity of staining and a subjective scale (− to +++) were used to classify staining patterns.

For Western blot analysis, cell extracts (50 μg of protein) were fractionated in SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane. Immunoblotting was performed using 1:5000 dilution of anti-FLAG (Sigma), anti-KLF-4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-VEGF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or anti-β-actin antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). Bands were detected by using a chemiluminescence detection kit (Pierce).

Reporter and Expression Plasmids

The 1.2 VEGF-CAT reporter plasmid was constructed by ligating a 1.2-kb promoter DNA fragment of the human VEGF gene as described before (16). SAF-1 expression plasmid, pcDFLAG-SAF-1, was prepared by inserting full-length SAF-1 cDNA with a FLAG tag into the pCDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) as described (17). HDAC2 and -3 and KLF-4 expression plasmids were kindly provided by Ed Seto and Shiva Swamynathan, respectively.

Preparation of Nuclear Extract and DNA Binding Assay

Preparation of nuclear extracts from MCF-10A, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and MDA-MB-468 cells and DNA binding assays were performed as described before (9) using a radiolabeled DNA with sequences from −135 to +29 of VEGF. In some binding reactions, antibodies against SAF-1 (9), KLF-4, Sp1, or normal IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were added to the reaction mixtures during a preincubation period of 30 min on ice.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and Re-ChIP

ChIP and re-ChIP assays were performed following a method as described (17) with minor modifications. Cells grown in culture were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min followed by addition of 0.125 mol/liter glycine for 5 min and washed in PBS buffer. Following lysis of the cells and sonication, DNA·protein complexes in the lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-KLF-4 or control normal IgG. After precipitation of the immunocomplex with protein G-agarose, followed by washing and extraction with elution buffer, re-ChIP assays were performed by immunoprecipitation with a second set of antibody, as indicated in the figure legends. After a second round of immunoprecipitation reaction, isolated DNA was used as template in PCR with specific primers spanning the target region of VEGF promoter. Primers used for amplification of human VEGF promoter were 5′-GAGCTTCCCCTTCATTGCGG-3′ and 5′-CGGCTGCCCCAAGCCTC-3′, which yields an amplicon of 219 bp.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using an RNA isolation kit (Qiagen). Relative expression levels of KLF-4 and VEGF were determined by quantitative real time RT-PCR using gene-specific primers. The cDNAs were prepared by reverse transcription from 0.5 μg of total RNA using TaqMan reverse transcription reagents and analyzed for KLF-4, VEGF, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) according to the manufacturer's protocol (Applied Biosystems, Invitrogen). Expression levels were normalized against the GAPDH gene. All experiments were done using biological triplicates and experimental duplicates.

Cell Migration Assay

HUVEC migration assay was performed as described earlier (9). In the HUVEC culture medium, CM derived from KLF-4 siRNA-transfected, control (scrambled) siRNA-transfected, SAF-1 siRNA-transfected, or pcDKLF-4- or pcDNA3- transfected MCF-7 or MDA-MB-231 cells were added. The cells that migrated onto the filter were counted manually by examination under a microscope.

Statistical Analyses

To compare multiple sets of data, a one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Fisher's least significant difference test was used. For paired data sets, a two-tailed t test was used. Values of p < 0.05 were considered to represent a significant difference.

RESULTS

SAF-1-mediated Induction of VEGF Is Higher in Breast Cancer Cells as Compared with Normal Breast Epithelial Cells

Previous studies identified SAF-1 to be a transcriptional inducer of VEGF in breast cancer cells (9). To assess the relative response of normal breast epithelial and breast carcinoma cells to SAF-1, transfection analysis was performed that showed that SAF-1 is much more effective (>5.0-fold versus 1.8-fold) in promoting VEGF expression in breast cancer cells as compared with that in MCF-10A normal breast epithelial cells (Fig. 1A). These results were in correlation with earlier findings obtained from normal human mammary epithelial cells (9). Specificity of the results in Fig. 1A was evaluated by examining the expression level of SAF-1 in all transfected cells, which showed a dose-dependent increase of SAF-1 protein levels following transfection of SAF-1 expression plasmids (Fig. 1B). VEGF mRNA and protein levels were analyzed in SAF-1-overexpressing transfected cells (Fig. 1, C and D). In correlation with the VEGF-CAT reporter expression, overexpression of SAF-1 could only marginally increase VEGF mRNA and protein levels in normal MCF-10A cells. Together, these results suggested a novel mode of regulation that may control VEGF expression in normal breast cells.

FIGURE 1.

SAF-1-induced VEGF expression is higher in breast cancer cells. A, MCF-10A, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and MDA-MB-468 cells were co-transfected with equal amounts (0.5 μg) of 1.2VEGF-CAT or pBLCAT3 plasmid and increasing concentrations of pcDFLAG-SAF-1 plasmid (0.5 and 1.0 μg), as indicated. Twenty four hours after transfection, CAT activity was determined using an equivalent amount of cell extracts. Relative CAT activity was determined by comparing the activities of transfected plasmids with that of pBLCAT3 and correcting for transfection efficiency (β-gal). Results represent an average of three separate experiments. *, p < 0.05. Inset, schematic of human VEGF promoter. B, Western blot assay of transfected cells for detection of SAF-1 expression in the same samples as shown in A. Equal protein amount of cell extracts (50 μg) was fractionated in a 5/11% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to PVDF membrane, and immunoblotted with an anti-FLAG antibody. Blots were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with β-actin antibody to confirm equal loading. C, total RNA isolated from untreated and pcDSAF-1 (1.0 μg)-transfected cells, as indicated, was subjected to quantitative RT-PCR analysis with primers specific for VEGF. The results were normalized to the level of GAPDH in each sample and represent an average of three separate experiments. *, p < 0.05. D, Western blot analysis of cell extracts (70 μg of protein) from untreated and pcDSAF-1 (1.0 μg)-transfected cells, as used in C, with anti-VEGF antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with β-actin antibody to confirm equal loading. Histograms summarize the Western blot results.

KLF-4 Acts as a Transcriptional Suppressor of VEGF by Directly Interacting with VEGF Promoter at Sites Overlapping SAF-1 Elements

We hypothesized that reduced levels of SAF-1-mediated transactivation of VEGF in normal breast cells could be the action of an abundantly present SAF-1 antagonist that, by reducing the interaction of SAF-1 with the VEGF promoter, lowers SAF-1 action. In such a scenario, the DNA-binding element of the antagonist protein should overlap with the SAF-1 DNA-binding element in the VEGF promoter. By using RSAT, a regulatory sequence analysis software tool (18), we identified the presence of multiple DNA-binding elements of the KLF-4 transcription factor in the VEGF promoter, some of which overlapped SAF-1 DNA-binding elements (Fig. 2A). A series of DNA binding assays indicated that indeed KLF-4 interacts with the VEGF promoter, and its element overlaps with the SAF-1 element (Fig. 2B). Three major DNA·protein complexes (a, b, and c) were seen to be formed by nuclear proteins, among which the level of complex b was at a markedly higher amount in all breast cancer cells but quite low in MCF-10A cells (Fig. 2B, lanes 2–5). In contrast, complex c was abundant in MCF-10A cells but low in breast cancer cells. We also noticed that complex b may not be a single complex but composed of multiple DNA·protein complexes. KLF-4 antibody completely abolished the DNA·protein complex c (Fig. 2B, lane 8), whereas SAF-1 antibody inhibited formation of complex b (Fig. 2B, lanes 7 and 12). The GC-rich region in the VEGF promoter (−109/−61) is also interacted by Sp1 transcription factor (19), and Sp1 is found to regulate VEGF expression in several cancer cell lines (20–23) as well as in hormonal regulation (24). Furthermore, in earlier studies, we and others (25, 26) have shown that SAF-1 and Sp1 can bind to the same DNA element and synergize each other's function. To determine whether Sp1 is involved in this process, Sp1 antibody was used, which supershifted a portion of complex b (Fig. 2B, lanes 9 and 14), and inclusion of both SAF-1 and Sp1 antibodies completely abolished complex b (Fig. 2B, lanes 10 and 15). The identity of complex a, which is present at almost the same level in all cells, is not clear from these results and remains to be defined. Together, these results showed abundant KLF-4 DNA binding activity with the VEGF promoter in normal MCF-10A cells but very little in several breast cancer cells (Fig. 2B, lanes 1–5). In correlation with the decreased KLF-4 DNA binding activity, the RNA and protein levels of KLF-4 were much less in breast cancer cells (Fig. 2, C and D).

FIGURE 2.

KLF-4 interacts with VEGF promoter. A, DNA sequences of VEGF from nucleotide position −119 to +5 contain the transcription start site, indicated by an arrow, and DNA-binding elements KLF-4 and SAF-1. B, nuclear extracts (10 μg of protein), as indicated, were incubated with 32P-labeled VEGF DNA containing sequences from −135 to +29. Resulting DNA·protein complexes (a, b, and c) were fractionated in a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. In some assays, antibodies to KLF-4, Sp1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), SAF-1, or normal IgG were included during a preincubation reaction. Migration positions of KLF-4-, SAF-1-, and Sp1-specific complexes are indicated. Supershift of the DNA·protein complex is indicated by ss. C, total RNA was subjected to quantitative RT-PCR analysis with primers specific for KLF-4. The results were normalized to the level of GAPDH in each sample. D, cell extracts (50 μg of protein) were fractionated in a 5/11% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to PVDF membrane, and immunoblotted with anti-KLF-4 antibody for Western blot (WB) analysis. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with β-actin antibody as a loading control.

Endogenous VEGF Expression Was Attenuated by KLF-4 Expression

To further understand the role of KLF-4 in regulating VEGF transcription in cancer cells, we examined the consequences of overexpression of KLF-4 in MDA-MB-231 cells. The increase of the KLF-4 protein level not only decreased VEGF promoter activity, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A, columns d–f), it also suppressed SAF-1-mediated induction of VEGF (Fig. 3A, columns g–k). In correlation, endogenous VEGF mRNA levels declined in a dose-dependent manner in KLF-4-overexpressing pcD-KLF-4 plasmid DNA-transfected MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 3B, columns d′–f′). Reciprocally, depletion of endogenous KLF-4 by transfection of cells with KLF-4 siRNAs significantly increased the transcription from VEGF promoter-reporter (Fig. 3C) and VEGF mRNA levels in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (Fig. 3, D and E). Stimulatory effect of KLF-4 siRNA in these cells was diminished when they were co-transfected with KLF-4 and SAF-1 siRNAs (Fig. 3, D and E). This finding suggested that SAF-1 is most likely involved in the increased VEGF expression when KLF-4 is depleted. The effect of KLF-4 depletion was also evident in normal MCF-10A breast cells as transfection of cells with KLF-4 siRNAs significantly improved pcD-SAF-1-mediated transcriptional activation of the VEGF promoter-reporter (Fig. 3F). Together these results showed that KLF-4 may function as a negative regulator of VEGF transcription, reduction of which can increase the level of VEGF in cancer cells.

FIGURE 3.

Overexpression of KLF-4 reduces VEGF expression in breast cancer cells. A, MDA-MB-231 cells were co-transfected with 1.2 VEGF CAT reporter plasmid (0.5 μg) and pcD-SAF-1 (0.5 μg) and pcD-KLF-4 (0.5, 0.75, 1.0, and 1.5 μg) expression plasmids, as indicated. Relative CAT activity was determined as described in Fig. 1A. The results represent an average of three independent experiments (*, p < 0.05). Inset shows protein expression (columns g′–k′) from KLF-4 and SAF-1 plasmids in transfected cells (columns g–k), which was assessed by Western blot (WB) analysis. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with β-actin antibody to confirm equal loading. B, VEGF mRNA level, after overexpression of KLF-4 in pcD-KLF-4 plasmid-transfected (0.5 and 1.0 μg) MDA-MB-231 cells, was determined by quantitative real time PCR analysis using the cDNA templates and the specific primers for GAPDH and VEGF. KLF-4 protein level in transfected cells was analyzed by Western blot (WB) analysis. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with β-actin antibody to confirm equal loading. C, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with 1.2 VEGF CAT reporter plasmids (0.5 μg). In some transfection reactions, 200 nmol of KLF-4 siRNA or scrambled siRNA (CTRL siRNA) of the same length were used. Relative CAT activity was determined as described in Fig. 1A. Results represent an average of three separate experiments (**, p < 0.05). D and E, VEGF mRNA levels in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively, after transfection of 200 nm of KLF-4 siRNA, scrambled siRNA (CTRL siRNA), and SAF-1 siRNA, as indicated. Quantitative real time PCR assays were performed using the cDNA templates and the specific primers for GAPDH and VEGF. VEGF mRNA levels in KLF-4 siRNA-transfected cells was further normalized with control siRNA-transfected cells. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments (**, p < 0.02; ***, p < 0.05). F, MCF-10A cells were transfected with 1.2 VEGF CAT reporter plasmid (0.5 μg). In some transfection reactions, 200 nm KLF-4 siRNA or scrambled RNA (CTRL siRNA) oligonucleotide of the same length and increasing concentrations (0.5, 0.75, and 1.0 μg) of SAF-1 expression plasmid, pcD-SAF-1, were added. Relative CAT activity was determined as described in Fig. 1A. Results represent an average of three separate experiments (*, p < 0.05).

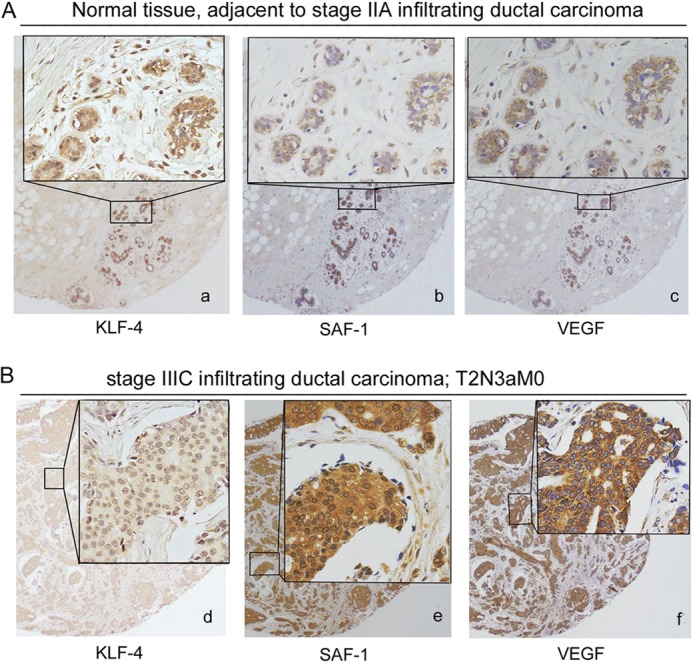

Expression of KLF-4 Is Reduced in Clinical Breast Cancer Tissues

A tissue microarray containing 30 breast cancer and 30 normal adjacent breast tissues was used for monitoring KLF-4 expression in clinical breast cancer specimens in patient-matched tumor and adjacent normal tissue pairs (Fig. 4). Nuclear and cytoplasmic staining of normal breast epithelium, ductal carcinoma in situ, and invasive carcinoma were analyzed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4). KLF-4 protein was at a well detectable level in normal breast tissues (Fig. 4A, panel a). In contrast, all breast tumor samples had much lower KLF-4 staining (Fig. 4B, panel d). We compared KLF-4 expression level with VEGF and SAF-1 in the serial sections of the same tissues, which indicated nominal expression of VEGF and SAF-1 in normal breast tissues (Fig. 4A, panels b and c) but very high expression in breast cancer tissues (Fig. 4B, panels e and f). Analysis of 30 different types of tumor samples, however, did not reveal any statistically significant association between KLF-4, SAF-1, or VEGF expression and estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and p53 status of the tumors. A summary of the histological and immunohistochemistry analyses is presented (Table 1).

FIGURE 4.

KLF-4 expression in clinical breast cancer and adjacent normal tissues. A, immunohistochemical analysis of KLF-4 (panel a), SAF-1 (panel b), and VEGF (panel c) in serial sections of normal breast tissues adjacent to cancer. B, immunohistochemical analysis of KLF-4 (panel d), SAF-1 (panel e), and VEGF (panel f) in serial sections of clinical breast cancer tissues. The insets represent higher magnification of the boxed area. A total of 60 breast tissue samples (30 cancer and 30 adjacent normal) were examined, and some representative samples are shown here. Pathological evaluation of the samples and the analysis of KLF-4, SAF-1 and VEGF expression are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

KLF-4, SAF-1, and VEGF expression in different stages of human breast cancer tissues

| Breast tissue | No. of samples | Stagea | LNb | KLF-4 levelc | SAF-1 levelc | VEGF levelc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infiltrating ductal carcinoma (n = 30) | 8 | IIA | 1/18 | + | ++ | ++ |

| 6 | IIB | 2/18 | + | ++ | ++ | |

| 6 | IIIA | 5/19 | + | +++ | +++ | |

| 6 | IIIC | 15/24 | + | +++ | +++ | |

| 4 | IV | 12/15 | + | +++ | +++ | |

| Adjacent normal tissue (n = 30) | 30 | 0 | 0 | +++ | + | + |

a Cancer stage was determined by following the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system.

b LN is metastatic lymph nodes/examined lymph nodes.

c A semi-quantitative estimate of KLF-4, SAF-1, and VEGF expression level was on combined score for the proportion of stained cells and the intensity of stain and following the criteria as described earlier (14, 15). Proportion score represented the estimated percentage of stained cells (0, <10%; 1, between 10 and 25%; 2, between 25 and 50%; 3, between 50 and 75%; 4, between 75 and 90%; 5, >90%). Intensity score corresponded to the average staining intensity of the cells (0, no staining; 1, weakly stained; 2, moderately stained; and 3, strongly stained). Levels of staining were derived as follows: samples with an intensity score of 0 or a proportion score of 0 were designated negative (−), and samples with intensity score of 1 and a proportion score of 1–2 were designated as weak (+). Samples with an intensity score of 2 and 3, and combined scores of 2–3, 4–6, and 7–8 were designated as weak (+), moderate (++), and strong (+++) expression, respectively.

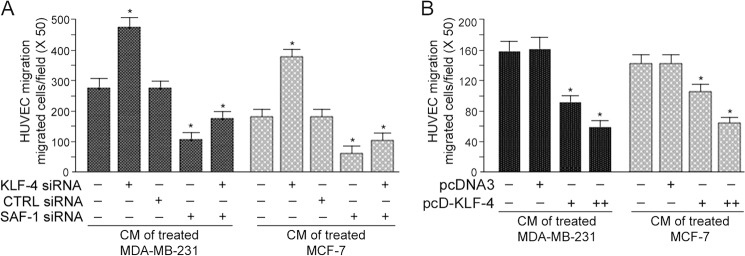

KLF-4 Deficiency Increases Angiogenic Potential of Breast Cancer Cells

One of the important properties of tumor cells is their increased VEGF-mediated angiogenesis, including cell migration. To evaluate whether KLF-4 regulates VEGF-mediated cell migration, we performed a transwell assay, in which the CM of KLF-4 knockdown and KLF-4-overexpressing cancer cells were used to monitor the motility of HUVECs. As shown in Fig. 5A, the number of migrated HUVECs was significantly higher in the wells in which CM from KLF-4 siRNA-transfected cancer cells was used. The number of migrated cells had a 1.66-fold increase as compared with that of CM derived from untreated or scrambled siRNA-transfected cells. SAF-1 siRNAs however had an opposite effect. However, when both KLF-4 and SAF-1 siRNAs were used, there was some increase in the HUVEC migration as compared with that obtained with SAF-1 siRNA alone. This result suggested that in addition to SAF-1, KLF-4 might be involved in quarantining some other positive regulators of VEGF expression. Consistent with the results obtained with specific siRNAs, HUVEC migration rate was significantly decreased (62%) in response to the use of CM derived from KLF-4-overexpressing cancer cells (Fig. 5B). Together, these results further strengthened the model that KLF-4 inhibits VEGF expression by acting as a negative transcriptional regulator.

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of KLF-4 increases and overexpression of KLF-4 reduces cell migration potential. A, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were transfected with KLF-4 siRNA, control siRNA (CTRL siRNA), or SAF-1 siRNA, as indicated. CM from these transfected cells were collected 24 h later. Culture media of HUVECs were fortified with the different CM preparations, and migrated cells were counted. Results represent mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05. B, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were transfected with increasing concentrations of pcDNA3 or pcD-KLF-4 plasmid DNA (0.0, 1.0, and 2.0 μg). Following transfection, CM were collected. Culture media of HUVECs were fortified with the different CM preparations, as indicated, and the migrated cells, following 24 h incubation, were counted. Results represent mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05.

KLF-4 Recruits HDACs to the VEGF Promoter for Functional Regulation

KLF-4 is seen to be associated with HDACs, including HDAC2 and HDAC3 in regulating gene expression (27–29). To assess whether HDAC2 and HDAC3 are recruited by KLF-4 at the VEGF promoter, we performed sequential ChIP-reChIP analysis. Cross-linked chromatin of MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cells was subjected to immunoprecipitation with the first antibody (ChIP analysis), and the resulting immunocomplex was subjected to immunoprecipitation with the second antibody, followed by semi-quantitative PCR analysis. These results showed the presence of KLF-4, HDAC2 and HDAC3, bound to the VEGF promoter in MCF-10A cells (Fig. 6A). However, these proteins were not present in any detectable levels in MDA-MB-231 cancer cells (Fig. 6B). As control, when immunoprecipitation was performed using normal IgG, no PCR-amplified product was seen, which indicated for the specific nature of the association between KLF-4, HDAC2, and HDAC3 proteins with the VEGF promoter (Fig. 6, A and B). We performed transient transfection assays to determine whether overexpression of KLF-4 and HDACs would inhibit expression of the VEGF promoter (Fig. 6C). Individual ectopic expression of KLF-4, HDAC2, and HDAC3 reduced 1.2VEGF-CAT reporter activity, but the effect was more pronounced, and the inhibition was synergistic when the cells were co-transfected with KLF-4, HDAC2, and HDAC3 expression plasmids (Fig. 6C). These results suggested that KLF-4, by recruiting HDAC2 and -3, functions as a transcriptional suppressor of VEGF, loss of which leads to overexpression of VEGF in breast cancer cells.

FIGURE 6.

KLF-4 recruits HDAC2 and -3 to VEGF promoter. A, MCF-10A cells were cross-linked with formaldehyde, and chromatin isolated from these cells was subjected to ChIP-reChIP analysis. ChIP was first performed by immunoprecipitating with anti-KLF-4, anti-HDAC2, anti-HDAC3, or CTRL IgG, as indicated. The eluent of each immunocomplex was further immunoprecipitated using anti-HDAC2, anti-HDAC3, or CTRL IgG, as indicated. The precipitated chromatin DNA or input DNA was used for PCR amplification using VEGF-specific primers. B, MDA-MB-231 cells were subjected to ChIP-reChIP analysis by following the method as described in A. C, MDA-MB-231 cells were co-transfected with pBLCAT3 (0.5 μg) or 1.2VEGF CAT reporter (0.5 μg) and a combination of pcD-KLF-4 (0.25 μg), pcD-HDAC2 (0.5 μg), and pcD-HDAC3 (0.5 μg) DNAs, as indicated. Relative CAT activity was determined, and the results represent an average of three separate experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

VEGF, the most potent tumor-angiogenesis factor, plays a crucial role in tumor angiogenesis and metastatic spread of cancer. Why normal cells do not produce as much VEGF, whereas cancer cells produce copious amount of this protein, is a subject of great interest. We report that in normal breast, KLF-4 transcription factor, by functioning as a transcriptional repressor, regulates VEGF expression. For potent regulatory effects, KLF-4 recruits epigenetic co-repressors, HDAC2 and HDAC3, at the VEGF promoter and further extends its inhibitory control by competing with the transcriptional inducer, SAF-1, whose DNA-binding element overlaps with the KLF-4 DNA-binding element. Although KLF-4 is abundantly expressed in normal breast, its level is markedly reduced in breast cancer. We provide evidence and a model illustrating how reduction of KLF-4 in breast cancer cells could result in a two-way stimulation of VEGF expression (Fig. 7). First, due to reduction of KLF-4 levels and reduction of functional KLF-4-HDAC association, transcription of VEGF gets inadequately suppressed. Second, by failing to compete with the transcriptional activator SAF-1, which is abundantly expressed in breast cancer cells (9), the decrease of the KLF-4·HDAC complex allows uninhibited SAF-1-mediated transcriptional induction of VEGF. Activation of SAF-1, a Cys2-His2 type zinc finger protein (30), in response to various inflammatory signals (25, 31–34) and phosphorylation by PKC (35), MAPK (36), PKA (37), and casein kinase II (38) leads to marked enhancement of its DNA binding ability. Together, these findings indicate that the KLF-4·HDAC complex may act as a molecular switch to dynamically regulate VEGF expression and play a major role in the increase of VEGF and enhanced VEGF-mediated angiogenesis in breast tumors. The KLF-4-HDAC-SAF1 molecular axis could be a new target in angiogenic therapy for breast cancer treatment.

FIGURE 7.

Model illustrating the role of KLF-4, HDACs, and SAF-1 in regulating VEGF expression. In normal breast cells, KLF-4 is abundantly present, which, upon association with HDAC2 and -3, interacts with VEGF promoter. The interaction of the KLF-4·HDAC complex with VEGF is subject to very little competition from the minimally active SAF-1, resulting in transcriptional suppression of VEGF. In breast cancer cells, low abundance of KLF-4 and high abundance of SAF-1, allows predominant SAF-1 interaction with VEGF promoter and SAF-1-mediated increase of VEGF transcription.

KLF-4 is a member of the Kruppel-like factor family of Cys2-His2 type zinc finger proteins; collectively, this family of proteins regulates a multitude of processes in normal tissue, including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, homeostasis, and self-renewal (10–12). KLF-4 is shown to play a key role in phenotypic switching and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, where loss of KLF-4 is shown to create a proinflammatory status due to inhibition of repression of basal and cytokine-mediated expression of a diverse set of proinflammatory factors (39, 40). KLF-4 exerts a profound anti-inflammatory effect by promoting the expression of several negative cell cycle regulatory genes, including p21 (41), p27, Mdm2, and retinoblastoma, and positive cell cycle regulatory genes, such as cyclin B1 (29), cyclinD1, and ornithine decarboxylase (42), and loss of KLF-4 is seen to contribute to the development and progression of gastric cancer (43) and skin cancer (44). Recently, KLF-4 was found to inhibit tumorigenic progression and metastasis in a mouse model of breast cancer (45). The consensus KLF-4 DNA-binding element is 5′-(G/A)(G/A)GG(C/T)G(C/T)-3′. The uniqueness of KLF-4 is that by being a Cys2-His2 type zinc finger protein (10–12), it can compete with the other zinc finger proteins because of the similarities in their DNA-binding elements. In the VEGF promoter, KLF-4 binds to the same region where SAF-1 interacts with the VEGF promoter (9) and thereby suppresses SAF-1 function. In addition to SAF-1, KLF-4 competes with the Sp1 transcription factor and down-regulates Sp1 function (43, 46); binding sites for Sp1 have been identified in the (G+C)-rich proximal promoter region of VEGF (19). Incidentally, Sp1 has been identified to be a positive regulator of VEGF expression in several cancers and instrumental in the proliferation of cancer cells (20–23). Results of Figs. 3, D and E, and 5A indicated that SAF-1 alone may not fully account for the compensatory effect of KLF-4-mediated repression of VEGF expression. KLF-4 may very well be competing for SAF-1 and some other positively acting regulators of VEGF, possibly Sp1.

Our finding of the involvement of HDAC2 and HDAC3 in the regulation of VEGF expression (Fig. 6) provides a link between engagements of HDAC proteins with VEGF expression. HDACs are a class of enzymes that remove acetyl groups from histones and nonhistone proteins and modulate gene transcription in coordination with other sequence-specific transcription factors (47–49). HDAC2 and HDAC3 belong to the class I type of HDACs and are a core component of multiprotein corepressor complexes, in which their activities are modulated via interactions with other proteins while being recruited by transcription factors to specific promoters. Deregulation of HDAC recruitment to specific promoters of genes involved in cell cycle progression and differentiation is suggested to be one of the mechanisms by which HDACs contribute to tumorigenesis (50, 51). Our results showed that in normal breast cells, KLF-4 recruits HDAC2 and -3 for synergistic levels of transcriptional suppression (Fig. 6A), which was markedly absent in breast cancer cells (Fig. 6B). We propose that loss of KLF-4-HDAC-mediated regulatory control creates an unbalanced transacetylation process that in turn overwhelms the transcription initiation machinery to promote an increase of VEGF transcription in breast cancer cells. Our findings are consistent with previous reports in which KLF-4 is seen to associate with HDACs and repress gene expression (27, 29, 52). It will be interesting to find if other genes, which are unregulated in cancer, are controlled in a similar fashion.

Identification of KLF-4-HDAC-mediated transcriptional repression of VEGF will also be useful in explaining the beginning of up-regulation of VEGF in the micro-tumors during “angiogenic switch.” Ample studies have confirmed that the tumors located at a distance to blood vessels can grow only up to a few millimeters in diameter. These clinically harmless micro-tumors can stay dormant for years, until the cells within the micro-tumors or in the surrounding region induce formation of new capillaries and blood vessels by activating the angiogenic switch (53–55). Thus, the angiogenic switch is a determining cellular event in cancer biology by permitting micro-metastases to undergo a transition from an avascular to a highly vascular state and progression toward malignancy. It also can play a role in the recurrence or relapse of cancer. We propose that de-repression of the novel KLF-4-HDAC-mediated transcriptional suppression of VEGF is one of the potential mechanisms that begin the increase of the VEGF level and create a pro-inflammatory environment in normal breast. As the process continues, it leads to the activation of other inflammation-responsive transcription factors and full-fledged increase of VEGF expression and tumor malignancy.

Reduced level of KLF-4 expression has been reported in a variety of human cancers, including gastric, colorectal, esophagus, stomach, bladder, lung, skin, prostate, and adult T-cell leukemia (43, 44, 56–61). These findings suggested for a role of KLF-4 as a potent tumor suppressor. In contrast, the role of KLF-4 in breast cancer is not as clear. Some reports have indicated that KLF-4 is overexpressed in breast cancers (62, 63), especially in the cancer stem cells (64), and knockdown of KLF-4 was shown to suppress cell migration and invasion in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (64). Contrary to these findings, several reports have indicated low level expression of KLF-4 in breast cancer. Immunohistochemistry analysis of breast cancer tissues indicated low KLF-4 protein levels in breast cancer and an association between the lower expression of KLF-4 with a higher recurrence rate of breast cancer (65). Gene expression data assembled in the Oncomine database also showed a decrease in KLF-4 gene transcripts in breast cancer (66). Cell lines derived from African American women, who have a higher rate of breast cancer-related morbidity due to increased metastases, are shown to contain less KLF-4 as compared with cell lines derived from Caucasian women (67). In correlation with gene expression analysis, KLF-4 protein levels and DNA binding activity were found to be highly reduced in many breast cancer cell lines, including T47D, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and ZR75-1 (68). Furthermore, forced expression of KLF-4 has been shown to inhibit the invasion rate of highly metastatic MDA-MB-231 cells and tumor progression in orthotopic mammary cancer models (45, 69). Consistent with these findings, knockdown of KLF-4 elevated estrogen-induced proliferation of MCF-7 cells suggesting that KLF-4 suppresses growth of breast cancer cells by inhibiting the binding of estrogen receptor α to estrogen-response elements in the promoter regions (66). In normal MCF-10A breast cells, silencing of KLF-4 alters epithelial cell morphology, indicating that KLF-4 plays a role in the maintenance of the epithelial phenotype and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (69). Altogether, these data suggest that KLF-4 can function as a tumor suppressor gene or an oncogene depending on the genetic context. Mechanistically, the opposing effect of KLF-4 may be linked to the functional status of p21WAF/CIP in the cell (70, 71). In cells that have functional p21WAF/CIP, KLF-4 is shown to act as a tumor suppressor, but in the absence of p21WAF/CIP or in the presence of RASV12-cyclin-D1 signaling, the anti-proliferative effect of KLF-4 may be counteracted to reveal an oncogenic function (70, 71). Further studies should reveal how a delicate balance of these regulatory molecules could affect the functional outcome of KLF-4 in cancer.

We show that successive binding of KLF-4 followed by HDACs to the VEGF promoter epigenetically repress VEGF transcription in normal breast cells. In breast cancer, de-repression of the KLF-4-HDAC molecular switch not only lifts the transcriptional suppression of VEGF but at the same time it permits SAF-1-mediated transcriptional increase of VEGF. Therapies directed against KLF-4-HDAC-SAF-1 module may be valuable against tumor angiogenesis. Future studies including in vivo models will be important to explore such possibilities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shiva Swamynathan and Ed Seto for the generous gifts of KLF-4 and HDAC expression plasmids, respectively.

This work was supported in part by grants from the United States Army Medical Research and Material Command and the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Missouri.

- SAF-1

- serum amyloid A-activating factor-1

- KLF-4

- Kruppel-like factor-4

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase

- CAT

- chloramphenicol acetyltransferase

- CM

- conditioned medium

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cell.

REFERENCES

- 1. Folkman J., Merler E., Abernathy C., Williams G. (1971) Isolation of a tumor factor responsible for angiogenesis. J. Exp. Med. 133, 275–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Engels K., Fox S. B., Whitehouse R. M., Gatter K. C., Harris A. L. (1997) Distinct angiogenic patterns are associated with high-grade in situ ductal carcinomas of the breast. J. Pathol. 181, 207–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferrara N. (1995) The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in pathological angiogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 36, 127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferrara N. (2002) Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in physiologic and pathologic angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. Semin. Oncol. 29, 10–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yoshiji H., Gomez D. E., Shibuya M., Thorgeirsson U. P. (1996) Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, its receptor, and other angiogenic factors in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 56, 2013–2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown L. F., Berse B., Jackman R. W., Tognazzi K., Guidi A. J., Dvorak H. F., Senger D. R., Connolly J. L., Schnitt S. J. (1995) Expression of vascular permeability factor (vascular endothelial growth factor) and its receptors in breast cancer. Hum. Pathol. 26, 86–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Van der Auwera I., Van Laere S. J., Van den Eynden G. G., Benoy I., van Dam P., Colpaert C. G., Fox S. B., Turley H., Harris A. L., Van Marck E. A., Vermeulen P. B., Dirix L. Y. (2004) Increased angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in inflammatory versus noninflammatory breast cancer by real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR gene expression quantification. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 7965–7971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jacobs E. J., Feigelson H. S., Bain E. B., Brady K. A., Rodriguez C., Stevens V. L., Patel A. V., Thun M. J., Calle E. E. (2006) Polymorphisms in the vascular endothelial growth factor gene and breast cancer in the Cancer Prevention Study II cohort. Breast Cancer Res. 8, R22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ray A., Dhar S., Ray B. K. (2011) Control of VEGF expression in triple-negative breast carcinoma cells by suppression of SAF-1 transcription factor activity. Mol. Cancer Res. 9, 1030–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shields J. M., Christy R. J., Yang V. W. (1996) Identification and characterization of a gene encoding a gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor expressed during growth arrest. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20009–20017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McConnell B. B., Yang V. W. (2010) Mammalian Kruppel-like factors in health and diseases. Physiol. Rev. 90, 1337–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Atkins G. B., Jain M. K. (2007) Role of Kruppel-like transcription factors in endothelial biology. Circ. Res. 100, 1686–1695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Allred D. C., Clark G. M., Elledge R., Fuqua S. A., Brown R. W., Chamness G. C., Osborne C. K., McGuire W. L. (1993) Association of p53 protein expression with tumor cell proliferation rate and clinical outcome in node-negative breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 85, 200–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bouras T., Southey M. C., Venter D. J. (2001) Overexpression of the steroid receptor coactivator AIB1 in breast cancer correlates with the absence of estrogen and progesterone receptors and positivity for p53 and HER2/neu. Cancer Res. 61, 903–907 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang L., Hoque A., Luo R. Z., Yuan J., Lu Z., Nishimoto A., Liu J., Sahin A. A., Lippman S. M., Bast R. C., Jr., Yu Y. (2003) Loss of the expression of the tumor suppressor gene ARHI is associated with progression of breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 3660–3666 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ray B. K., Shakya A., Ray A. (2007) Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in arthritic joint is regulated by SAF-1 transcription factor. J. Immunol. 178, 1774–1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kumar D., Ray A., Ray B. K. (2009) Transcriptional synergy mediated by SAF-1 and AP-1: critical role of N-terminal polyalanine and two zinc finger domains of SAF-1. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 1853–1862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thomas-Chollier M., Sand O., Turatsinze J. V., Janky R., Defrance M., Vervisch E., Brohée S., van Helden J. (2008) RSAT: regulatory sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W119–W127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Finkenzeller G., Sparacio A., Technau A., Marmé D., Siemeister G. (1997) Sp1 recognition sites in the proximal promoter of the human vascular endothelial growth factor gene are essential for platelet-derived growth factor-induced gene expression. Oncogene 15, 669–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stoner M., Wormke M., Saville B., Samudio I., Qin C., Abdelrahim M., Safe S. (2004) Estrogen regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression in ZR-75 breast cancer cells through interaction of estrogen receptor α and SP proteins. Oncogene 23, 1052–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abdelrahim M., Smith R., 3rd, Burghardt R., Safe S. (2004) Role of Sp proteins in regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression and proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 64, 6740–6749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deacon K., Onion D., Kumari R., Watson S. A., Knox A. J. (2012) Elevated SP-1 transcription factor expression and activity drives basal and hypoxia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 39967–39981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Song Y., Wu J., Oyesanya R. A., Lee Z., Mukherjee A., Fang X. (2009) Sp-1 and c-Myc mediate lysophosphatidic acid-induced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in ovarian cancer cells via a hypoxia-inducible factor-1-independent mechanism. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 492–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stoner M., Wang F., Wormke M., Nguyen T., Samudio I., Vyhlidal C., Marme D., Finkenzeller G., Safe S. (2000) Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in HEC1A endometrial cancer cells through interactions of estrogen receptor α and Sp3 proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 22769–22779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ray A., Schatten H., Ray B. K. (1999) Activation of Sp1 and its functional co-operation with serum amyloid A-activating sequence binding factor in synoviocyte cells trigger synergistic action of interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 in serum amyloid A gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 4300–4308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Song J., Ugai H., Nakata-Tsutsui H., Kishikawa S., Suzuki E., Murata T., Yokoyama K. K. (2003) Transcriptional regulation by zinc-finger proteins Sp1 and MAZ involves interactions with the same cis-elements. Int. J. Mol. Med. 11, 547–553 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Evans P. M., Zhang W., Chen X., Yang J., Bhakat K. K., Liu C. (2007) Kruppel-like factor 4 is acetylated by p300 and regulates gene transcription via modulation of histone acetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33994–34002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wei X., Xu H., Kufe D. (2007) Human mucin 1 oncoprotein represses transcription of the p53 tumor suppressor gene. Cancer Res. 67, 1853–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoon H. S., Yang V. W. (2004) Requirement of Kruppel-like factor 4 in preventing entry into mitosis following DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5035–5041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ray A., Ray B. K. (1998) Isolation and functional characterization of cDNA of serum amyloid A-activating factor that binds to the serum amyloid A promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 7327–7335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ray B. K., Ray A. (1997) Involvement of an SAF-like transcription factor in the activation of serum amyloid A gene in monocyte/macrophage cells by lipopolysaccharide. Biochemistry 36, 4662–4668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ray A., Ray B. K. (1996) A novel cis-acting element is essential for cytokine-mediated transcriptional induction of the serum amyloid A gene in nonhepatic cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 1584–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ray B. K., Chatterjee S., Ray A. (1999) Mechanism of minimally modified LDL-mediated induction of serum amyloid A gene in monocyte/macrophage cells. DNA Cell Biol. 18, 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ray A., Kumar D., Ray B. K. (2002) Promoter-binding activity of inflammation-responsive transcription factor SAF is regulated by cyclic AMP signaling pathway. DNA Cell Biol. 21, 31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ray A., Fields A. P., Ray B. K. (2000) Activation of transcription factor SAF involves its phosphorylation by protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39727–39733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ray A., Yu G. Y., Ray B. K. (2002) Cytokine-responsive induction of SAF-1 activity is mediated by a mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1027–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ray A., Ray P., Guthrie N., Shakya A., Kumar D., Ray B. K. (2003) Protein kinase A signaling pathway regulates transcriptional activity of SAF-1 by unmasking its DNA-binding domains. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 22586–22595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tsutsui H., Geltinger C., Murata T., Itakura K., Wada T., Handa H., Yokoyama K. K. (1999) The DNA-binding and transcriptional activities of MAZ, a Myc-associated zinc finger protein, are regulated by casein kinase II. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 262, 198–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hamik A., Lin Z., Kumar A., Balcells M., Sinha S., Katz J., Feinberg M. W., Gerzsten R. E., Edelman E. R., Jain M. K. (2007) Kruppel-like factor 4 regulates endothelial inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13769–13779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Owens G. K., Kumar M. S., Wamhoff B. R. (2004) Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol. Rev. 84, 767–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang W., Geiman D. E., Shields J. M., Dang D. T., Mahatan C. S., Kaestner K. H., Biggs J. R., Kraft A. S., Yang V. W. (2000) The gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor (Kruppel-like factor 4) mediates the transactivating effect of p53 on the p21WAF1/Cip1 promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18391–18398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wei D., Kanai M., Huang S., Xie K. (2006) Emerging role of KLF4 in human gastrointestinal cancer. Carcinogenesis 27, 23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kanai M., Wei D., Li Q., Jia Z., Ajani J., Le X., Yao J., Xie K. (2006) Loss of Kruppel-like factor 4 expression contributes to Sp1 overexpression and human gastric cancer development and progression. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 6395–6402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li J., Zheng H., Yu F., Yu T., Liu C., Huang S., Wang T. C., Ai W. (2012) Deficiency of the Kruppel-like factor KLF4 correlates with increased cell proliferation and enhanced skin tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis 33, 1239–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yori J. L., Seachrist D. D., Johnson E., Lozada K. L., Abdul-Karim F. W., Chodosh L. A., Schiemann W. P., Keri R. A. (2011) Kruppel-like factor 4 inhibits tumorigenic progression and metastasis in a mouse model of breast cancer. Neoplasia 13, 601–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ai W., Liu Y., Langlois M., Wang T. C. (2004) Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) represses histidine decarboxylase gene expression through an upstream Sp1 site and downstream gastrin responsive elements. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8684–8693; Correction (2004) J. Biol. Chem.279, 27830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wade P. A. (2001) Transcriptional control at regulatory checkpoints by histone deacetylases: molecular connections between cancer and chromatin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 693–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wolffe A. P. (1996) Histone deacetylase: a regulator of transcription. Science 272, 371–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Burke L. J., Baniahmad A. (2000) Co-repressors 2000. FASEB J. 14, 1876–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marks P. A., Richon V. M., Breslow R., Rifkind R. A. (2001) Histone deacetylase inhibitors as new cancer drugs. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 13, 477–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thiagalingam S., Cheng K.-H., Lee H. J., Mineva N., Thiagalingam A., Ponte J. F. (2003) Histone deacetylases: unique players in shaping the epigenetic histone code. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 983, 84–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kee H. J., Kook H. (2009) Kruppel-like factor 4 mediates histone deacetylase inhibitor-induced prevention of cardiac hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 47, 770–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bergers G., Benjamin L. E. (2003) Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Baeriswyl V., Christofori G. (2009) The angiogenic switch in carcinogenesis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 19, 329–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hanahan D., Folkman J. (1996) Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell 86, 353–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yu T., Chen X., Zhang W., Li J., Xu R., Wang T. C., Ai W., Liu C. (2012) Kruppel-like factor 4 regulates intestinal epithelial cell morphology and polarity. PLoS ONE 7, e32492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang N., Liu Z.-H., Ding F., Wang X.-Q., Zhou C.-N., Wu M. (2002) Down-regulation of gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor expression in esophageal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 8, 966–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ohnishi S., Ohnami S., Laub F., Aoki K., Suzuki K., Kanai Y., Haga K., Asaka M., Ramirez F., Yoshida T. (2003) Downregulation and growth inhibitory effect of epithelial-type Kruppel-like transcription factor KLF4, but not KLF5, in bladder cancer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 308, 251–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bianchi F., Hu J., Pelosi G., Cirincione R., Ferguson M., Ratcliffe C., Di Fiore P. P., Gatter K., Pezzella F., Pastorino U. (2004) Lung cancers detected by screening with spiral computed tomography have a malignant phenotype when analyzed by cDNA microarray. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 6023–6028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yasunaga J., Taniguchi Y., Nosaka K., Yoshida M., Satou Y., Sakai T., Mitsuya H., Matsuoka M. (2004) Identification of aberrantly methylated genes in association with adult T-cell leukemia. Cancer Res. 64, 6002–6009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wang J., Place R. F., Huang V., Wang X., Noonan E. J., Magyar C. E., Huang J., Li L.-C. (2010) Prognostic value and function of KLF4 in prostate cancer: RNAa and vector-mediated overexpression identify KLF4 as an inhibitor of tumor cell growth and migration. Cancer Res. 70, 10182–10191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Foster K. W., Frost A. R., McKie-Bell P., Lin C. Y., Engler J. A., Grizzle W. E., Ruppert J. M. (2000) Increase of GKLF messenger RNA and protein expression during progression of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 60, 6488–6495 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pandya A. Y., Talley L. I., Frost A. R., Fitzgerald T. J., Trivedi V., Chakravarthy M., Chhieng D. C., Grizzle W. E., Engler J. A., Krontiras H., Bland K. I., LoBuglio A. F., Lobo-Ruppert S. M., Ruppert J. M. (2004) Nuclear localization of KLF4 is associated with an aggressive phenotype in early-stage breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 2709–2719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yu F., Li J., Chen H., Fu J., Ray S., Huang S., Zheng H., Ai W. (2011) Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) is required for maintenance of breast cancer stem cells and for cell migration and invasion. Oncogene 30, 2161–2172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nagata T., Shimada Y., Sekine S., Hori R., Matsui K., Okumura T., Sawada S., Fukuoka J., Tsukada K. (2012) Prognostic significance of NANOG and KLF4 for breast cancer. Breast Cancer, in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Akaogi K., Nakajima Y., Ito I., Kawasaki S., Oie S. H., Murayama A., Kimura K., Yanagisawa J. (2009) KLF4 suppresses estrogen-dependent breast cancer growth by inhibiting the transcriptional activity of ERα. Oncogene 28, 2894–2902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yancy H. F., Mason J. A., Peters S., Thompson C. E., 3rd, Littleton G. K., Jett M., Day A. A. (2007) Metastatic progression and gene expression between breast cancer cell lines from African American and Caucasian women. J. Carcinog. 6, 8–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Miller K. A., Eklund E. A., Peddinghaus M. L., Cao Z., Fernandes N., Turk P. W., Thimmapaya B., Weitzman S. A. (2001) Kruppel-like factor 4 regulates laminin α 3A expression in mammary epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 42863–42868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yori J. L., Johnson E., Zhou G., Jain M. K., Keri R. A. (2010) Kruppel-like factor 4 inhibits epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through regulation of E-cadherin gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 16854–16863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rowland B. D., Bernards R., Peeper D. S. (2005) The KLF4 tumour suppressor is a transcriptional repressor of p53 that acts as a context-dependent oncogene. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 1074–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rowland B. D., Peeper D. S. (2006) KLF4, p21 and context-dependent opposing forces in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 11–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]