Abstract

Gorham's disease is a rare disorder characterized by clinical and radiological disappearance of bone by proliferation of non-neoplastic vascular tissue. The disease was first reported by Jackson in 1838 in a boneless arm. The disease was then described in detail in 1955 by Gorham and Stout. Since then, about 200 cases have been reported in the literature, with only about 28 cases involving the spine. We report 2 cases of Gorham's disease involving the spine and review related literature to gain more understanding about this rare disease.

Keywords: Gorham's disease, Spine

Introduction

Primary idiopathic osteolysis is rare. It is characterized by the spontaneous onset of bone resorption without known causative factors. Torg et al. [1] classified the osteolysis into four types. Macpherson et al. [2] then added a fifth type called Winchester syndrome (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classifiaction of idiopathic osteolysis

Gorham's disease is one of the five types of idiopathic osteolysis. It is differentiated from other types by the presence of a benign vascular tumor causing osteolysis. Unlike multicentric osteolysis, Gorham's disease neither has a hereditary pattern nor any associated nephropathy. It can occur at any age. It is monocentric and does not have any predilection for a carpo-tarsal area [3]. The disease was first described by Jackson in 1838 [4,5]. In 1955, Gorham and Stout [6] tabulated 24 previously reported cases and the condition then came to be known as Gorham's disease [4,5]. Various other names have been described in the literature; those most commonly used are "vanishing bone disease", "phantom bone disease", and "disappearing bone disease" [7].

The exact etiology of the disease is not understood. Initially, Gorham and Stout believed that trauma initiated local vascular granulation tissue that brought about osteolysis by hyperemia, change in the pH, and mechanical forces. Since then, various theories have been presented to explain the etiology of this disease, such as an increase in the number of osteoclasts, hydrolytic enzymes produced by perivascular cells, interleukin 6, etc. [7].

The pathological process is well understood. It is a non-neoplastic vascular tissue similar to haemangioma or lymphangioma that replaces the bone. Various treatment modalities have been described for treatment of Gorham's disease, both medical and surgical. Non surgical management could be bisphosphonates, alpha 2B interferon, and radiation therapy, while surgical treatment can be resection of the lesion with or without reconstruction with a bone graft or prosthesis [7]. We describe two cases of Gorham's disease that involved the spine and presented with deformity and paraplegia.

Case Reports

1. Case 1

A 15-year-old boy presented at with a history of progressive deformity of the back and dull continuous back ache for the past six months, exertional dyspnoea for one month, progressive weakness of both lower limbs for the past 15 days, and loss of bladder and bowel control for the past two days. He gave a history of trauma (fall from a height of 3 feet) 7 years previously, following which he noticed progressive deformity of the chest.

On examination he showed a kyphoscoliotic deformity in the upper thoracic region, where the third to seventh ribs were absent on the left side, with visible cardiac pulsations. Complete loss of motor power was apparent in both lower limbs with complete absence of sensations from below the umbilicus with exaggerated deep tendon reflexes, extensor plantar, and clonus bilaterally.

Radiological featuresof the thoracic spine and chest are described in Figs. 1, 2. A chest X-ray taken four years previously at 11 years of age showed almost normal appearing ribs with normal thoracic vertebrae, indicating that the disease was not congenital and was progressive. All the biochemical investigations performed were within normal limits, ruling out any metabolic or endocrine pathology. All the imaging modalities were consistent with angiomatosis lesions affecting the bone.

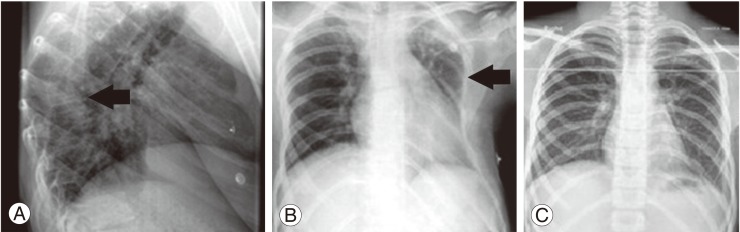

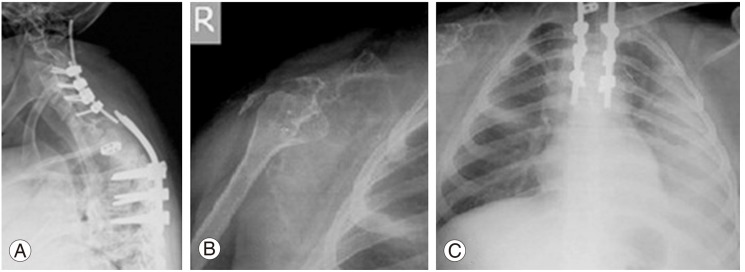

Fig. 1.

(A) X-ray thoracic spine lateral view showing kyphosis with D6 wedging. (B) Chest X-ray showing absent third to seventh ribs on the left side with mild left sided scoliosis. (C) Chest X-ray taken four years previously at 11 years of age showed almost normal appearing ribs with normal thoracic vertebrae.

Fig. 2.

(A) Computed tomography scan images of chest and spine showing hypoplastic sternum and ribs on left side, ill-defined lytic lesions in the body vertebrae with kyphosis. (B) Magnetic resonance images of thoracic spine showing hyper signal intensities on both T1 and T2 weighted images within the bodies of T3 to T6 vertebrae.

The patient underwent Pedicle screw fixation, laminectomyand deformity correction. The resected bone samples were sent for histopathological examination (Fig. 3). Intraoperatively, the bones were found to have a thin cortex and appeared to be honeycomb-like. Increased vascularity of the bones was observed and the morphology of the posterior elements was altered. The hold of the screws in the diseased vertebra was reasonably good. Good cord pulsations were seen after decompression. A chest tube was inserted on the left side due to an incidental pleural tear. On the second postoperative day, the drain was removed and the patient was made to sit up-right. The patient was administered bisphosphonates and was referred to Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (Fig. 4).

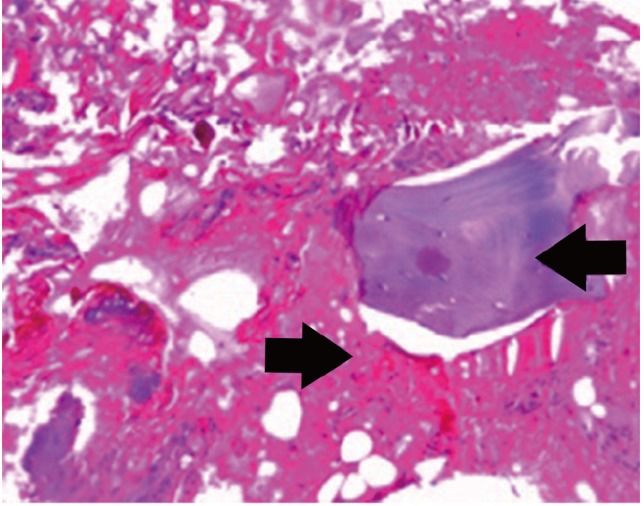

Fig. 3.

Histological image (H&E, ×40), showing thin walled blood vessels with hemorrhage and scanty bone. No cellular atypia, inflammatory cell infiltration or osteoclasts were seen; these features suggest benign angiomatous lesion.

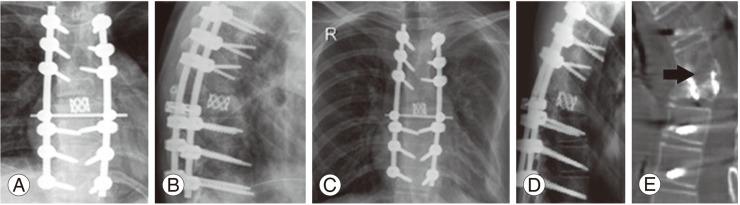

Fig. 4.

(A, B) Immediate postoperative X-ray thoracic spine anterioposterior and lateral view showing correction of the kyphoscoliotic deformity. (C-E) X-ray anteroposterior, lateral view, and computed tomography saggital images at 1 year follow up showing no progression of the deformity or osteolysis with bony bridge across the two vertebrae.

The patient recovered well postoperatively. At 4 weeks he was able to sit on his own, was able to walk with minimal support, and the neurology improved to American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) grade D. The patient was reviewed at 1 year follow up. He was asymptomatic without any progression of the disease clinically or radiologically.

2. Case 2

A 23-year-old male patient presented to us in June 2011 with a deformity of the back, weakness of both lower limbs, and with a history of multiple surgeries on the back. At three years of age, spontaneous disappearance of the right clavicle and upper humerus was noticed without any preceding trauma. Biopsy was taken from the lesion and diagnosis of Gorham's disease was made based on the histopathological examination of the tissue. The disease was subsequently not progressive. In May 2010, he noticed progressive deformity of the upper back, spasticity, and an altered gait. He was diagnosed with myelopathy and kyphotic deformity of the spine. On August ninth 2010 he pedicle screw instrumentation with decompression of the cord. The patient experienced an uneventful post-op period. His spasticity reduced and his gait improved over a period of two months and he was then able to walk normally. On May 25th 2011, a routine follow up X-ray showed breaking of the implant for which a revision surgery was performed the same day. Post-surgically, the patient developed complete weakness of both lower limbs with loss of bladder and bowel control. He was taken for immediate decompression. As the patient's neurology did not improve, a revision decompression was performed on 3 days later. The patient noticed the return of some movement in his right lower limb a few days after surgery. His bladder control returned one month later. He was referred to us for rehabilitation (Figs. 5, 6).

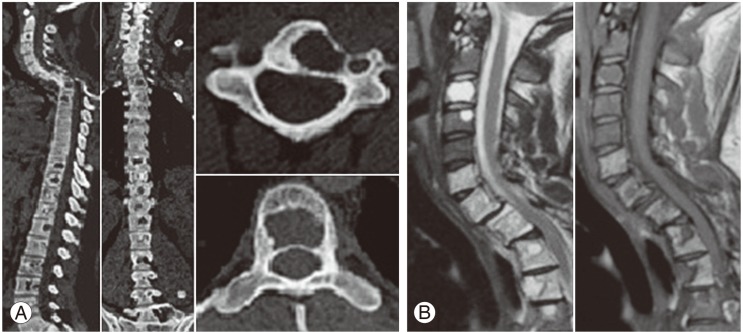

Fig. 5.

(A) Computed tomography scan images showing multiple lytic lesions within the body involving multiple vertebrae and kyphotic deformity at D1 and D2. (B) Magnetic resonance images of spine showing hypersignal intensity on T1 and mixed signal intensity on T2 weighted images within the body of the vertebra.

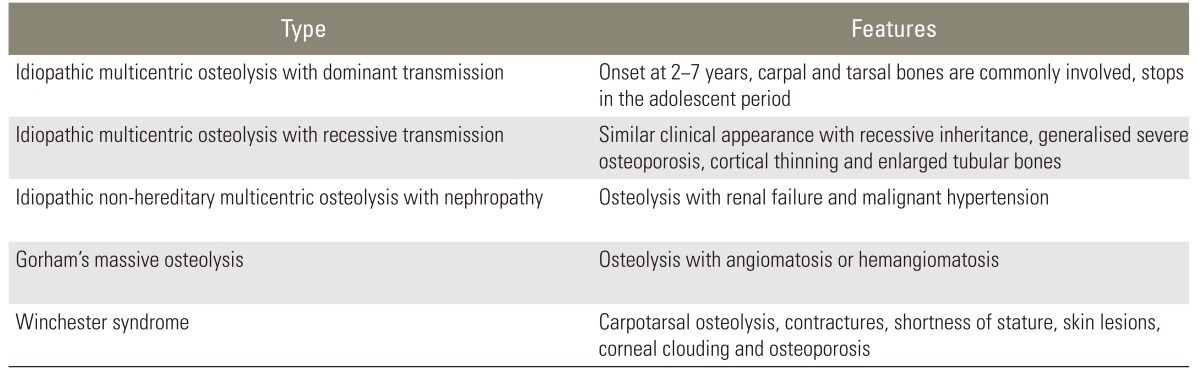

Fig. 6.

(A) X-ray cervical and thoracic spine anterioposterior view showing broken implant at cervicothoracic junction. (B) X-ray right shoulder showing osteolysis involving Scapula and Head of Humerus. (C) Chest X-ray posterioanterior view showing left side pleural effusion.

On examination, the patient showed dyspnoea, tachypnoea, and paradoxical breathing. Neurological examination revealed complete absence of motor power on the left lower limb and the power in the right lower limb was 1-2/5. Sensation was decreased from T5 below. Deep tendon reflexes were exaggerated with ankle clonus and extensor plantars. A loss of the rounded contour was observed on the right shoulder with painless exaggerated passive movements. A chest X-ray revealed pleural effusion on the left side. Chylous looking fluid was aspirated from the left side of the chest and on examination showed lymphocytes. The patient was booked for a thoracic duct ligation. He was also given the option of radiotherapy and pleural ablation. The patient refused any of these treatments. Since the patient's condition remained stable and the osteolysis was not progressing, he was kept under observation.

After 8 months of rehabilitation, the motor power in the lower limbs gradually improved and he was able to stand and walk in parallel bars with the help of left Anklefoot Orthrosisand bilateral knee gaiters. The disease did not show any progression clinically.

Discussion

Gorham's syndrome is a rare disease with only 200 cases reported in the literature [5]. Even though the majority of the cases show spontaneous arrest [5], life threatening complications may occur due to involvement of the spine, viscera or chest resulting in chylothorax [6]. Involvement of the spine is extremely rare [5]. In their review, Aizawa et al. [4] found 28 cases of Gorham's disease with spinal involvement reported in the literature. They proposed a treatment protocol for managing such cases. Medications, radiotherapy or observation were advised for those without any deformity, while surgical resection was advised for small lesions with deformity and long posterior fusion for larger lesions [4]. However, neurological deficits were not included in their treatment protocol. They also reported poor results after surgical intervention in spinal disease with resorption of graft and failure to achieve stability in 5 of the 8 cases reviewed [4]. Chylothorax is another complication resulting in high mortality [7], for which various treatment modalities have been described such as radiation, pleurodesis, thoracic duct ligation, etc. [8].

In the 2 cases of Gorham's disease with spinal involvement, both were managed surgically and had good functional outcome. In our first case, the probable cause of improvement in neurology from ASIA A to ASIA D over a 1 month period was the short duration of progressive deficits (15 days), early surgical intervention, and good rehabilitation. In our second case, even though the patient had good improvement after the first spinal surgery, his neurology deteriorated after the second surgery, which could be explained by an intra operative insult to the spinal cord. However, it was possible to achieve a stable spine and aided ambulatory status 8 months after the final procedure. Chylothorax in our second patient was resolved with only repeated aspirations. Both our cases showed spontaneous arrest which is probably the natural history of the disease.

Gorham's disease with spinal involvement is extremely rare. Spinal disease remains silent until deformity or neurological deficits develop. Hence, we recommend screening of the spine in the case of Gorham's disease of the shoulder or chest to discount secondary involvement. Asymptomatic spinal disease can be managed with radiation and bisphosphonates, while those with deformity or neurological deficits require early surgical decompression and long posterior instrumented fusion.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Torg JS, DiGeorge AM, Kirkpatrick JA, Jr, Trujillo MM. Hereditary multicentric osteolysis with recessive transmission: a new syndrome. J Pediatr. 1969;75:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(69)80395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macpherson RI, Walker RD, Kowall MH. Essential osteolysis with nephropathy. J Can Assoc Radiol. 1973;24:98–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardegger F, Simpson LA, Segmueller G. The syndrome of idiopathic osteolysis. Classification, review, and case report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:88–93. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B1.3968152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aizawa T, Sato T, Kokubun S. Gorham disease of the spine: a case report and treatment strategies for this enigmatic bone disease. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005;205:187–196. doi: 10.1620/tjem.205.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruggieri P, Montalti M, Angelini A, Alberghini M, Mercuri M. Gorham-Stout disease: the experience of the Rizzoli Institute and review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:1391–1397. doi: 10.1007/s00256-010-1051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorham LW, Stout AP. Massive osteolysis (acute spontaneous absorption of bone, phantom bone, disappearing bone); its relation to hemangiomatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37:985–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel DV. Gorham's disease or massive osteolysis. Clin Med Res. 2005;3:65–74. doi: 10.3121/cmr.3.2.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee WS, Kim SH, Kim IH, et al. Chylothorax in Gorham's Disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:826–829. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.6.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]