Abstract

Salmonella is an animal and human pathogen of worldwide concern. Surveillance programs indicate that the incidence of Salmonella serovars fluctuates over time. While bacteriophages are likely to play a role in driving microbial diversity, our understanding of the ecology and diversity of Salmonella phages is limited. Here we report the isolation of Salmonella phages from manure samples from 13 dairy farms with a history of Salmonella presence. Salmonella phages were isolated from 10 of the 13 farms; overall 108 phage isolates were obtained on serovar Newport, Typhimurium, Dublin, Kentucky, Anatum, Mbandaka, and Cerro hosts. Host range characterization found that 51% of phage isolates had a narrow host range, while 49% showed a broad host range. The phage isolates represented 65 lysis profiles; genome size profiling of 94 phage isolates allowed for classification of phage isolates into 11 groups with subsequent restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis showing considerable variation within a given group. Our data not only show an abundance of diverse Salmonella phage isolates in dairy farms, but also show that phage isolates that lyse the most common serovars causing salmonellosis in cattle are frequently obtained, suggesting that phages may play an important role in the ecology of Salmonella on dairy farms.

Keywords: Salmonella, bacteriophage, dairy farms

1. Introduction

Salmonella is an important pathogen of humans and animals and represents a serious public health concern worldwide (Scallan et al., 2011; Galanis et al., 2006). An estimated 1 million domestically acquired human salmonellosis cases and more than 400 salmonellosis associated deaths occur annually in the US (Scallan et al., 2011). While Salmonella can cause clinical disease in a large variety of animals, including cattle, it is also commonly isolated from the feces of animals that do not show symptoms of salmonellosis. In one study (Van Kessel et al., 2008), Salmonella was isolated from 8% of asymptomatic cattle. In another study in the US, 27–31% of dairy farms were found to have cows that shed Salmonella; on these farms between 5.4 to 7.3% of the cattle were found to shed Salmonella (USDA/APHIS, 2003). Salmonella may therefore be a transient member of the microbial community in the bovine gastrointestinal tract (Callaway et al., 2005). A large variety of food products have been linked to human salmonellosis cases, including poultry, low moisture dry foods, and food products of bovine origin such as beef, milk, cheese and other dairy products (Callaway et al., 2005). In addition, human salmonellosis cases and outbreaks have also been linked to direct contact with different infected animal species, including reptiles, rodents, poultry, and cattle (Hoelzer et al., 2011b).

Salmonella enterica comprises more than 2,600 serovars. The most common serovars vary by geographic region as well as animal sources (Galanis et al., 2006; CDC, 2009), and serovar-specific prevalences can change over time (CDC, 2008; CDC, 2009). For instance, in 2007 Salmonella serovars Typhimurium, Newport, Agona, Dublin, and Montevideo were most commonly associated with cattle in the US (CDC, 2008), while this had shifted to serovars Newport, Typhimurium, Orion, Cerro, and Dublin by 2008 (CDC, 2009). The most common bovine-associated serovars isolated in a study in upstate New York in 2008/09 included serovars Kentucky, Meleagridis, Cerro, Typhimurium, and Newport (Cummings et al., 2010). These shifts in predominant Salmonella serovars could be attributed to different factors, including acquisition of immunity to the predominant serovars, genetic adaptation to bovine hosts of specific serovars or strains within a serovar, management interventions (e.g., antibiotic therapy and vaccinations) that are more effective against certain serovars, and killing by virulent phages (Faruque et al., 2005; Foley et al., 2011).

Predation by bacteriophages affects bacterial populations in a variety of ways (Casjens, 2005). Bacteriophages enhance diversity among bacterial genotypes by selectively killing the competitive dominant, the most abundant genotype – a concept referred to as “killing the winner” (Weinbauer and Rassoulzadegan, 2004). Bacteriophages have been shown in some studies to be at least ten fold more abundant than their bacterial hosts (Casjens, 2005; Casjens, 2008). However, while a large body of data exists on the Salmonella serovar diversity associated with human and animal disease (e.g., CDC Salmonella Annual Summary and WHO Global Salm-Surv (Galanis et al., 2006; CDC, 2009)), our understanding of Salmonella phage diversity and the role of phages in the ecology and serovar diversity of Salmonella is still limited. Some studies have though shown considerable diversity among Salmonella phages isolated from swine effluent lagoons, human sewage, and swine and poultry feces (Andreatti Filho et al., 2007; Callaway et al., 2010; McLaughlin et al., 2006). One study reported isolation of phages representing different phage families and numerous different host ranges from 26 samples collected from 26 different sites (e.g., broiler farms, abattoirs, and waste water plants) in southern England (Atterbury et al., 2007). In addition, some studies have reported high abundance of Salmonella phages, including one study that found up to 2.1×109 PFU/ml in samples collected from swine effluent lagoons. Some Salmonella phages have also been characterized by whole genome sequencing, including the phages Felix 01 and V01 (Pickard et al., 2010; Whichard et al., 2010). Overall, at least 25 Salmonella phage genomes have been reported; genome sizes reported ranged from 33 to 240 kb (Hooton et al., 2011b; Kropinski et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012; Whichard et al., 2010).

This study examines the presence and diversity of Salmonella phages present on dairy farms with previous history of Salmonella isolation to improve our understanding of Salmonella phage diversity associated with cattle, which are an important natural host for Salmonella. Our data not only support that a considerable diversity of Salmonella phage isolates is present on dairy farms, but also found that farms characterized by a high prevalence of a specific Salmonella serovar often allowed for frequent isolation of phages that infect the Salmonella serovar predominant on a given farm, indicating the establishment of host-phage systems on a given farm.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection

A total of 13 dairy farms (Table 1) located in New York State were sampled for Salmonella phages between June 2008 and February 2009. These farms were part of a larger longitudinal study on Salmonella prevalence and diversity in environmental and fecal samples from cattle without clinical signs (Cummings et al., 2010); the 13 farms enrolled in this study were conveniently selected from farms that had a history of Salmonella presence. Salmonella serovars previously isolated on these farms included Anatum (2 farms), Mbandaka (1 farm), Typhimurium (1 farm), Kentucky (3 farms), Paratyphi B var. java (1 farm), Cerro (2 farms), Newport (1 farm), and Montevideo (1 farm); in addition both serovars Cerro and Thompson were isolated on one farm (Table 1). For two of these farms information on the predominant serovar was only available after samples were collected for phage isolation. Three farms (farms 3, 6 and 9) were sampled twice with at least one month interval between samplings. At each farm visit, two manure samples, one from manure storage and one from the animal holding area, were collected for phage isolation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of dairy farms in this study and summary of phage isolation results

| Farm information

|

No. of positive samples | Number of phage isolates obtained on specific serovar (no. of phage isolates from manure storage/holding area)b

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farm ID | Prevalence (%)a | Serovar history | Typhimurium | Newport | Dublin | Kentucky | Anatum | Mbandaka | Cerro | Total phages purified | |

| 1 | 2 | Anatum | 2 | 0 | 5 (4/1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1/1) | nt | 7 (5/2) |

| 2 | 1 | Mbandaka | 2 | 2 (0/2) | 3 (3/0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0/1) | 3 (1/2) | nt | 9 (4/5) |

| 3 | <1 | Typhimurium | 2 | 1 (1/0) | 1 (0/1) | 3c | 0 | nt | nt | nt | 2 (1/1) |

| 3 | <1 | Typhimurium | 2 | 3 (2/1) | 3 (1/2) | 2 (1/1) | 0 | nt | nt | nt | 8 (4/4) |

| 4 | 3 | Kentucky | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | nt | nt | nt | 0 |

| 5 | <1 | Paratyphi B var. Java | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | nt | nt | nt | 0 |

| 6 | 15 | Cerro/Thompson | 1 | 1 (0/1) | 1 (0/1) | 3 (0/3) | 2 (0/2) | nt | nt | 2 (0/2) | 9 (0/9) |

| 6 | 15 | Cerro/Thompson | 2 | 1c | 0 | 1 (0/1) | 2c | nt | nt | 3 (1/2) | 4 (1/3) |

| 7 | 1 | Anatum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | nt | nt | 0 |

| 8 | 20 | Cerro | 2 | 3 (1/2) | 3 (3/0) | 2 (2/0) | 0 | nt | nt | 11 (10/1) | 19 (16/3) |

| 9 | 15 | Newport | 2 | 2 (2/0) | 6 (3/3) | 3 (3/0) | 3 (3/0) | nt | nt | nt | 14 (11/3) |

| 9 | 15 | Newport | 2 | 1c | 7 (2/5) | 1 (1/0) | 1c | nt | nt | nt | 8 (3/5) |

| 10 | 1 | Montevideod | 2 | 1 (1/0) | 1 (1/0) | 2 (1/1a) | 0 | 4 (3/1) | nt | nt | 8 (6/2) |

| 11 | 9 | Kentucky | 2 | 0 | 1 (0/1) | 2 (1/1) | 0 | nt | nt | nt | 3 (1/2) |

| 12 | 13 | Kentucky | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1/1) | 0 | nt | nt | nt | 2 (1/1) |

| 13 | 51 | Cerroe | 2 | 2 (1/1) | 4 (2/2) | 1 (1/0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1/1) | 7 (5/2) | 16 (10/6) |

| Total phages purified | 25 | 15 | 35 | 18 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 23 | 108 (62/46) | ||

The within-herd prevalence of Salmonella shedding was estimated as the number of cattle positive for Salmonella/ divided by the number of cattle tested (composite farm data reported by Cummings et al., 2010)

nt: Not tested; indicates that a given host strain was not used with the samples from a farm

Phages were detected but could not be successfully propagated.

Serovar information was not available at the sample date, hence predominant serovar was not used for phage isolation.

Serovar information was not available at the sample date, however all the seven serovar were used for phage isolation.

2.2. Bacteriophage isolation procedures

Salmonella phages were isolated using (i) a direct isolation procedure without phage enrichment and (ii) isolation after phage enrichment with a multi-strain Salmonella cocktail, using procedures adapted from previous publications (Andreatti Filho et al., 2007; Higgins et al., 2005). For direct isolation, aliquots of the manure samples were mixed at a 1:10 ratio with salt magnesium (SM) buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH: 7.5], 0.1 M NaCl, 8 mM MgSO4), followed by a two step filtration process through a 0.45-μm bottle top filter and a 0.2-μm syringe-attached filter. Separate 100 μl aliquots of the filtrate were mixed with 300 μl aliquots of 1:10 dilutions of stationary phase cultures of different Salmonella host strains, representing approx. 108 CFU/ml (Table 2). After addition of 4 ml of 0.7% Trypticase Soy Agar (TSA) tempered to 55°C, the mixture was poured onto Petri dishes with a bottom layer of 1.5% TSA, followed by 12 to 18 h incubation at 37ºC. For phage enrichment, aliquots of the same samples used for direct detection were mixed at a 1:10 ratio with Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB) followed by addition of a 1 ml host strain cocktail representing an overnight culture of at least 4 Salmonella host strains (Table 2). These phage enrichment cultures were then incubated at 37ºC for 16 to 18 h, followed by two step filtration and phage isolation using the TSA overlay procedure and multiple Salmonella hosts as detailed above for direct isolation.

Table 2.

Salmonella isolates used for phage isolation and host range analysis

| Strain ID (FSL)a | Salmonella serovar | Source | % (number) of LP that infect each strainb | % (number) of phage isolates that infect each strainc | % (number) of farms where phages infecting a given strain were isolatedd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strains used for isolation and host range analysis | |||||

| A4-525 | Anatum | Bovine | 21.2 (23) | 28.5 (18) | 54 (7) |

| R8-242 | Cerro | Bovine | 44.4 (48) | 49.2 (31) | 62 (8) |

| S5-368 | Dublin | Bovine | 28.7 (31) | 38.0 (24) | 85 (11) |

| S5-431 | Kentucky | Bovine | 15.7 (17) | 19.0 (12) | 15 (2) |

| A4-793 | Mbandaka | Bovine | 19.4 (21) | 33.3 (21) | 54 (7) |

| S5-548 | Newport | Bovine | 41.6 (45) | 49.2 (31) | 62 (8) |

| A4-737 | Typhimurium | Bovine | 26.8 (29) | 41.2 (26) | 38 (5) |

| Strains used for host range analysis only | |||||

| S5-390 | 4,5,12:i:- | Human | 36.1 (39) | 49.2 (31) | 63 (8) |

| S5-667 | Agona | Bovine | 15.7 (17) | 22.2 (14) | 38 (5) |

| R8-092 | Corvallis | Human | 7.4 (8) | 12.7 (8) | 31 (4) |

| S5-373 | Braenderup | Human | 2.7 (3) | 4.7 (3) | 23 (3) |

| R8-798 | Weltevreden | Human | 5.5 (6) | 9.5 (6) | 23 (3) |

| S5-371 | Enteritidis | Human | 19.4 (21) | 26.9 (17) | 38 (5) |

| S5-455 | Heidelberg | Human | 5.5 (6) | 7.9 (5) | 23 (3) |

| S5-506 | Infantis | Human | 19.4 (21) | 21 (13) | 38 (5) |

| S5-406 | Javiana | Human | 18.5 (20) | 25.4 (16) | 38 (5) |

| S5-474 | Montevideo | Bovine | 13.8 (15) | 23.8 (15) | 54 (7) |

| S5-917 | Muenster | Bovine | 5.5 (6) | 9.5 (6) | 23 (3) |

| S5-515 | Newport | Human | 49.0 (53) | 55.5 (35) | 62 (8) |

| R8-376 | Oranienburg | Bovine | 7.4 (8) | 9.5 (6) | 31 (4) |

| S5-369 | Saintpaul | Human | 16.6 (18) | 22.2 (14) | 31 (4) |

| S5-454 | Panama | Human | 16.6 (18) | 20.6 (13) | 38 (5) |

| S5-464 | Stanley | Human | 18.5 (20) | 25.4 (16) | 38 (5) |

| S5-370 | Typhimurium | Human | 26.8 (29) | 41.2 (26) | 38 (5) |

| S5-961 | Virchow | Human | 7.4 (8) | 12.7 (8) | 46 (6) |

| B1-011 | E. coli | Unspecified | 17.5 (19) | 22.2 (14) | 38 (5) |

The full strain ID includes the prefix FSL (e.g., FSL A4-525)

A total of 65 lysis profiles (LP) were found among the phages tested

A total of 108 phage isolates were characterized

A total of 13 farms were included in this study

Salmonella host strains used for detection and enrichment always included 4 isolates representing serovars Typhimurium, Newport, Dublin, and Kentucky (Table 1); serovars Typhimurium, Newport, and Dublin were selected as they represented the most common serovars isolated from cattle in the US in 2007 (CDC, 2008); serovar Kentucky was included as it represented the most common serovar isolated from asymptomatic cattle in New York in 2007/08 based on data available at the time our study was initiated (Cummings, personal communication). For those farms where serovar information for previously isolated Salmonella was available at the time of sample collection, an isolate with the Salmonella serovar previously found on a given farm (i.e., serovars Anatum, Cerro, and Mbandaka, Table 1), was also included in (i) the cocktail used for enrichment and (ii) the isolates used for phage isolation.

Phage isolation plates from both direct isolation and isolation after enrichment were evaluated for presence of phage plaques after incubation at 37ºC for 12 to 18 h. If confluent lysis was observed on a given plate (i.e., if individual plaques could not be distinguished), the plate was flooded with 10 ml of SM buffer, the resulting suspension was filtered, and serial dilutions were re-plated for isolation on a given host (Bielke et al., 2007). Phage isolation and purification were performed using procedures similar to those previously described (Andreatti Filho et al., 2007; Bielke et al., 2007). Briefly, a plaque representing each distinct plaque morphology identified on a given plate was collected with a sterile Pasteur pipette and suspended in 100 μl of 0.9% NaCl. Tenfold serial dilutions of the suspension were prepared and plated onto TSA agar. This serial passage procedure was repeated for at least three times, until only a single plaque morphology was observed. Plates from the final serial passage were flooded with 10 ml of SM buffer, incubated for 3 h at room temperature, followed by addition of chloroform (to a final concentration of 0.2% v/v), centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, and filtered with a 0.2-μm filter. Phage stocks were stored at 4ºC (Bielke et al., 2007) and phage titers were determined by spotting serial dilutions of phage stocks on a Salmonella host lawn as previously described (Andreatti Filho et al., 2007; Atterbury et al., 2007; Bielke et al., 2007).

2.3. Characterization of bacteriophage lysis profiles on different hosts

For each phage isolate, lysis profiles were determined using an Escherichia coli strain and 25 Salmonella isolates that represented 23 different serovars; for two common serovars (i.e., Typhimurium and Newport) two Salmonella isolates representing different PFGE patterns were chosen (Table 2). Lysis profiles were determined essentially as described previously (Holmfeldt et al., 2007). Briefly, cultures of the host strains grown for 16 to 18 h in TSB at 37°C were used to prepare a soft agar (TSA 0.7%) host cell lawn. Lysis profiles were determined by spotting 5 μl of approx. 2×105 PFU/ml phage stocks, on different host cell lawns. For eight phage isolates (i.e., SP-022, SP-059, SP-079, SP-087, SP-090, SP-092, SP-095, and SP-096), the obtained titer was 6×103 to 2×104 (Suppl. Table 1), and these lower titers were used for host range determinations. Salmonella reference phage Felix 01 (Felix d’Herelle Collection, Laval University, Quebec, Canada) was used as positive control. Plates were examined for host cell lysis after 16 to 18 h incubation at 37ºC. The presence of plaques was indicative of lysis and a score of plus (+) was assigned; phage isolates that did not yield plaques on a given host were assigned a score of minus (−). Host range determinations were conducted in two independent replicates; if a phage isolate lysed a given strain in at least one of the experiments, this strain was classified as susceptible. Susceptibility scores for each Salmonella strain were used to assign a “lysis profile” (LP) number to each phage isolate; an identical LP number indicates that two phage isolates lysed the same host strains. Lysis profiles for the 25 Salmonella hosts and E. coli were also used to perform a cluster analysis to allow for identification of phage isolates with similar lysis profiles. Lysis profiles were analyzed by hierarchical clustering analysis with Ward’s method of binary distance, using the R software (version 2.10.0; R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria [http://www.R-project.org]). Phage isolate and host strain relatedness were represented as a heatmap.

2.4. Bacteriophage nucleic acid isolation

Isolation of phage nucleic acids was performed using a phenol/chloroform procedure based on the Lambda phage DNA isolation protocol previously described (Sambrook and Russel, 2001) with small modifications. Namely, removal of bacterial nucleic acids with DNase I (Promega, Madison, WI) (5μg/ml) and RNase A (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (30μg/ml), was performed after instead of before precipitation of phages with polyethylene-glycol. After phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, nucleic acids were dissolved in 50–100 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA; pH 8.0) and quantified using OD260 values determined with a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop products, Wilmington, DE).

2.5. Bacteriophage genome size determination

Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) was used to estimate bacteriophage genome sizes for 94 phage isolates; these phage isolates were selected so that at least one representative isolate with a unique combination of lysis profile, isolation host, plaque morphology, and farm source was used. Agarose plugs for PFGE were prepared by mixing 1 μg of phage nucleic acid (in 50 μl of TE) with 100 μl of 0.5% SKG agarose (Lonza, Rockland, ME). Plugs were loaded into 1% SKG agarose gels and electrophoresis was performed in 0.5X TBE buffer (pH 8.0) using a Bio-Rad CHEF DRII system. PFGE was performed for 22 h with 0.5 to 5s of switch time as previously described (Holmfeldt et al., 2007). Size markers included (i) a CHEF DNA Size Standards 8–48 kb ladder and (ii) CHEF DNA Size Standard λ ladder 0.05–1 Mb (both from Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) (Stenholm et al., 2008). If nucleic acid degradation was observed for a given phage, 50 μM thiourea was added to the electrophoresis buffer (Murase et al., 2004). Phage isolates that represented two or more bands were heat treated at 75ºC for 15 min before plug preparation to resolve cohesive ends (Klumpp et al., 2008). PFGE gels were analyzed with Bionumerics version 4.5 (Applied Maths, Austin, TX).

2.6. Restriction analysis of bacteriophage genomes

Phage isolates representing identical genome sizes and similar or identical lysis profiles were further characterized using genomic EcoRI restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. If phage isolates proved resistant to EcoRI digestion, additional enzymes (i.e., RsaI, KpaI, HpaI, PsaI, and SalI) were used for RFLP analysis; all restriction enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). Restriction digests were performed for 16 h at 37ºC with 150 ng of bacteriophage DNA, followed by electrophoresis using 0.7% agarose gels (Promega, Madison, WI). Restriction patterns were analyzed using Bionumerics version 4.5. Similarity analyses were performed using a Dice coefficient and clustering was performed using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA).

3. Results

3.1. Salmonella phages are common on dairy farms

With the sampling scheme used (i.e., collection and phage testing of two manure samples per farm visit), we were able to isolate Salmonella phage isolates from ten of the thirteen farms where samples were collected (Table 1). For the three farms where samples were collected on two visits (i.e., farms 3, 6, and 9) phage isolates were obtained from samples collected during both visits. Among the 13 sample sets with at least one phage-positive sample (i.e., 7 farms with one sample visit and 3 farms with two sample visits), both samples (manure storage and manure from holding area) were positive for 12 sets, while for one set only the sample from the holding area was positive for phages (Table 1). Overall, 25 of the 32 samples tested yielded Salmonella phage isolates that could be further propagated.

A total of 108 Salmonella-infecting phage isolates were obtained, purified, and characterized (Table 1). In addition 10 putative phage plaques, which all were small, did not yield phage isolates that could be propagated; similar difficulties propagating phages with very small plaques was reported for isolation of shiga-toxin producing E. coli phages from beef and sewage samples (Imamovic and Muniesa, 2011; Muniesa et al., 2004). Plaque size ranged from approx. 0.5 mm to 5 mm and plaques observed on the initial isolation plate included plaques with clear or turbid lysis (see Suppl. Table 1). A total of 62 phage isolates were obtained from manure storage samples, while 46 phage isolates were obtained from samples from the manure holding area. Overall, 98 phage isolates (90%) were obtained using the enrichment protocol, while 10 phage isolates were obtained with the direct isolation protocol (these phage isolates were obtained from two samples from farm 8, and one sample from each farm 9 and 13). For these samples, phage titers were 1×104/g and 1.5×104 PFU/g (farm 8, holding area and manure storage, respectively, both determined on Cerro host); 5×103 PFU/g (farm 9, holding area, determined on Newport host), and 5×103 PFU/g (farm 13, manure storage, determined on Cerro host).

Among the four Salmonella serovars used for phage isolation on all samples, serovars Newport, Dublin, and Typhimurium yielded the most phage isolates, while only few phage isolates were obtained on serovar Kentucky as host (Table 1). Among the 32 samples tested, 16, 12, and 11 yielded phage isolates on Newport, Dublin, and Typhimurium hosts, respectively. Salmonella Cerro also was the host for isolation of a large number of phage isolates (23, see Table 1), despite the fact that this serovar was only used as host strain for eight samples collected from the three farms (6, 8, and 13) with a history of Salmonella Cerro isolation (two sets of two samples were collected from farm 6). On two of the farms that yielded phage isolates on a Salmonella Cerro host, phages infecting this host were found at high levels (see above).

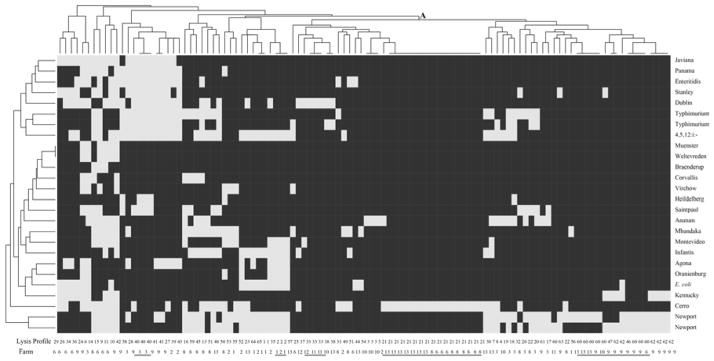

3.2. Salmonella phages isolated on dairy farms represent diverse lysis profiles including narrow and wide host range phages

Characterization of the lysis patterns for 108 phage isolates, allowed classification of these phage isolates into 65 different lyses profiles (based on lysis patterns for 25 Salmonella hosts and one E. coli host; Table 2). While 53 phage isolates (representing 46 lysis patterns) were characterized by a broad host range (defined as lysing between 4 and 18 strains), 55 phage isolates (representing 20 lysis patterns) were characterized by a narrow host range (lysing one to three strains); the cut-off between narrow and wide host range was set arbitrarily at 4. The most common lysis profile (LP) was LP21, which is a narrow host range lysis pattern, characterized by clear lysis of only Salmonella Cerro (see heatmap in Fig. 1). LP21 was represented by 17 phage isolates obtained from three different farms (farms 6, 8, and 13), which were characterized by a high prevalence of Salmonella Cerro (Table 1). Among the host strains tested, the most susceptible Salmonella serovars were serovars Newport, Cerro, 4,5,12:i:-, Dublin and Typhimurium, and the most insensitive were serovars Braenderup, Heidelberg, Weltevreden, Muenster and Corvallis (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Heat map representation of lysis profiles of the 108 phage isolates tested on 26 host strains.

Host strains are shown on the vertical axis. Phages are shown on the horizontal axis; for each phage the lysis profile (LP) and source farm are indicated on the bottom of the figure; phage isolates with identical LP types isolated from different farms are underlined in the figure. Light grey areas indicate lysis, dark grey areas indicate no lysis. Clustering was performed using Ward’s method of binary distance; the letter “A” marks one cluster that includes phage isolates that lysed between 1 and 6 host strains; phage isolates in the other clusters lysed between 6 and18 host strains.

Cluster analyses of lysis profiles identified one major cluster (marked as “A” in Fig. 1) that contained 67 phages representing 32 lysis profiles (e.g., LP21, LP33, LP60 and LP62); all phage isolates in this cluster were characterized by lysis of 1 to 6 host strains. The other phage isolates represented a number of clusters; phage isolates in these clusters lysed between 6 and 18 host strains.

For 6 out of the 10 farms where phages were isolated, we obtained at least one phage isolate that was able to lyse the host strain that represented the predominant serovar found on that farm. For the other 4 farms, none of the phage isolates obtained was able to lyse the predominant serovar found on a given farm; predominant serovars on these farms were Kentucky (2 farms), Anatum, and Montevideo (Table 3). When farms were classified into “high Salmonella prevalence” and “low Salmonella prevalence” farms (with an arbitrary cut-off of 10% prevalence; Table 3), we found that narrow host range phages infecting the predominant serovar were found on four of the five “high prevalence farms” (farms 6, 8, 9 and 13). Only a single narrow host range phage infecting the predominant serovar was isolated from the five low prevalence farms (i.e., from a sample collected on farm 2).

Table 3.

General host range characteristics of phage isolates obtained from different farms

| Farm no. | Prevalence (%)a | Predominant Salmonella serovar on farm | No. of narrow host range phages isolatedb | No. of narrow host range phages lysing the farm predominant serovar | No. of wide host range phages isolatedc | No. of wide host range phages lysing the farm predominant serovar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low prevalence farms (<10%) | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | Anatum | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | Mbandaka | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

| 3d | <1 | Typhimurium | 1 | 0 | 9 | 9 |

| 10 | 1 | Montevideo | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 9 | Kentucky | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| High prevalence farms (>10%) | ||||||

| 6d | 15 | Cerro/Thompson | 6 | 4 | 7 | 5 |

| 8 | 20 | Cerro | 9 | 9 | 10 | 7 |

| 9d | 15 | Newport | 13 | 13 | 9 | 4 |

| 12 | 13 | Kentucky | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 51 | Cerro | 11 | 7 | 5 | 4 |

The within-herd prevalence of Salmonella shedding was estimated as the number of cattle positive for Salmonella/ divided by the number of cattle tested (composite farm data reported by Cummings et al., 2010)

Phages were classified as narrow host range phages if they lysed 1 to 3 of the Salmonella strains tested.

Phages were classified as wide host range phages if they lysed 4 to 18 of the Salmonella strains tested.

For farms 3, 6, and 12, phage numbers represent phage isolates obtained from samples collected during the two visits.

3.3. Estimated genome sizes of the Salmonella phage isolates range from 22 to 156 kb

PFGE analysis of nucleic acids isolated from 94 representatives phage isolates (selected as detailed in section 2.5) found estimated bacteriophage genome sizes ranging from 22 to 156 kb (Table 4). PFGE identified nine phages that appeared to have cohesive ends. For these phages, the initial PFGE analysis showed two or more bands, with the larger bands typically representing sizes that were multiples of the size of the smaller band (e.g., approx. 60 and approx. 120 kb). Subsequent PFGE analysis of the same phage DNA after heating at 75°C for 15 min yielded a single band (of the smaller size). For an additional two phages that showed two bands in the initial PFGE analysis, two bands remained after heat treatment. Re-purification of these phages over multiple rounds ultimately yielded two plaques (one turbid and one clear); while propagation of phages from the turbid plaque succeeded, re-growth of the clear plaque continued to yield two plaque phenotypes (turbid and clear), possibly suggesting co-cultures with dependence of the phage yielding the clear plaque on the other phage that yields turbid plaques.

Table 4.

Phage genome sizes for 94 phage isolatesa

| Genome size (kb) | Lysis Profile No. (LP) (serovar(s) infected) | No. phage isolates | No. farms (farm ID) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | LP1 (4,5 INF NEW ECO) | 2 | 1 (1) |

| 22 | LP2 (4,5 MON INF NEW ORA AGO ECO) | 3 | 2 (1,2) |

| 22 | LP23 (CER 4,5 INF NEW ORA AGO ECO) | 1 | 1 (13) |

| 22 | LP35 (DUB 4,5 MON INF NEW ORA AGO ECO) | 1 | 1 (1) |

| 22 | LP64 (DUB CER 4,5 INF NEW ECO) | 1 | 1 (1) |

| 22 | LP65 (4,5 INF NEW AGO ECO) | 1 | 1(2) |

| 22 (coh.)b | LP11 (ANA MBA CER DUB ENT 4,5 JAV KEN STA MON NEW WEL MUE ECO) | 1 | 1 (6) |

| 22 (coh.)b | LP24 (CER DUB ENT JAV KEN PAN COR ORA WEL SAI AGO MUE VIR ECO) | 1 | 1 (9) |

| 22 (coh.)b | LP54 (MBA ECO) | 1 | 1 (13) |

| 40 | LP9 (ANA MAB CER DUB BRA JAV KEN HEI MON INF NEW WEL MUE) | 1 | 1 (6) |

| 40 | LP21 (CER) | 17 | 3 (6,8,13) |

| 40 | LP25 (CER DUB INF) | 1 | 1 (6) |

| 40 | LP38 (DUB TYP) | 1 | 1 (13) |

| 40 (coh.)b | LP40 (DUB TYP ENT 4,5 JAV PAN HEI STA SAI) | 1 | 1 (3) |

| 40–42 | LP10 (ANA MBA CER DUB ENT 4,5 JAV KEN PAN STA MON INF NEW COR WEL MUE VIR) | 1 | 1 (6) |

| 40–60 | LP48 (MAB CER TYP 4,5 INF NEW SAI) | 1 | 1 (13) |

| 48 | LP3 (ANA) | 3 | 1 (10) |

| 48 | LP4 (ANA 4,5 NEW) | 1 | 1 (10) |

| 48 | LP5 (ANA CER) | 1 | 1 (2) |

| 48 | LP60 (NEW) | 1 | 1 (6) |

| 56 | LP18 (ANA TYP 4,5 HEI NEW) | 1 | 1 (3) |

| 56 | LP31 (CER TYP ENT) | 1 | 1 (8) |

| 56 | LP45 (INF MBA TYP 4,5 INF NEW COR) | 1 | 1 (8) |

| 56 | LP46 (KEN NEW ECO) | 1 | 1 (9) |

| 56 | LP50 (MBA CER DUB TYP 4,5 MON NEW SAI) | 1 | 1 (8) |

| 56 | LP60 (NEW) | 5 | 2 (9,11) |

| 56 | LP61 (NEW ANA) | 1 | 1 (9) |

| 56 | LP62 (NEW KEN) | 6 | 1 (9) |

| 56 | LP63 (NEW STA) | 1 | 1 (9) |

| 60 (coh.)b | LP8 (ANA CER TYP 4,5 NEW) | 1 | 1 (3) |

| 60 (coh.)b | LP19 (ANA TYP 4,5 NEW) | 1 | 1 (3) |

| 60 (coh.)b | LP32 (CER TYP STA NEW SAI) | 1 | 1 (8) |

| 60 (coh.)b | LP59 (MBA TYP INF NEW COR SAI) | 1 | 1 (8) |

| 60 (coh.)b | LP60 (NEW) | 2 | 2 (10,13) |

| 62 | LP20 (ANA TYP NEW SAI) | 1 | 1 (3) |

| 62 | LP28 (CER DUB TYP ENT 4,5 JAV PAN STA SAI) | 1 | 1 (3) |

| 62 | LP49 (MBA CER 4,5) | 1 | 1 (2) |

| 62 | LP60 (NEW) | 1 | 1 (13) |

| 72 | LP33 (DUB) | 3 | 2 (11,12) |

| 72 | LP37 (DUB MON) | 1 | 1 (12) |

| 72 | LP38 (DUB TYP) | 1 | 1 (10) |

| 72 | LP39 (DUB TYP ENT 4,5 JAV PAN AGO) | 1 | 1 (2) |

| 72 | LP40 (DUB TYP ENT 4,5 JAV PAN HEI STA SAI) | 1 | 1 (3) |

| 72 | LP41 (DUB TYP ENT 4,5 JAV PAN STA NEW AGO) | 1 | 1 (9) |

| 72 | LP43 (DUB TYP ENT 4,5 PAN STA AGO) | 1 | 1 (2) |

| 72 | LP58 (MBA TYP ENT 4,5 JAV PAN STA NEW AG) | 1 | 1 (9) |

| 72 | LP60 (NEW) | 1 | 1 (10) |

| 86 | LP52 (MBA CER MON NEW VIR) | 1 | 1 (2) |

| 86 | LP53 (MBA CER PAN HEI MON NEW ORA VIR) | 1 | 1 (2) |

| 86 | LP55 (MBA MON NEW VIR) | 1 | 1 (1) |

| 86 | LP56 (MBA NEW) | 1 | 1 (1) |

| 86 | LP57 (MBA TYP 4,5 VIR) | 1 | 1 (13) |

| 156 | LP14 (ANA MBA CER TYP BRA 4,5 JAV PAN STA MON NEW COR SAI) | 1 | 1 (3) |

| 156 | LP15 (ANA MBA CER TYP ENT BRA 4,5 JAV PAN STA MON NEW WEL SAI MUE VIR) | 1 | 1 (8) |

| 156 | LP22 (TYP NEW SAI) | 1 | 1 (8) |

| 156 | LP36 (DUB ENT 4,5 JAV KEN STA ECO) | 1 | 1 (6) |

| 156 | LP40 (DUB TYP ENT 4,5 JAV PAN HEI STA SAI) | 1 | 1 (9) |

| 156 | LP42 (DUB TYP ENT 4,5 PAN HEI SAI) | 1 | 1 (9) |

| Degraded | LP29 (CER JAV KEN STA ECO) | 1 | 1 (6) |

| Degraded | LP34 (DUB 4,5 JAV KEN STA AGO ECO) | 1 | 1 (6) |

| Degraded | LP44 (ENT ECO) | 1 | 1 (6) |

Overall, 94 phage isolates were selected for phage genome determination; phage isolates were selected so that at least one representative isolate with a unique combination of lysis profile, isolation host, plaque morphology, and farm source was used.

“coh.” indicates phages that were identified as showing cohesive ends.

Abbreviations: AGO: Agona, ANA Anatum, BRA: Braenderup, CER: Cerro, COR: Corvallis, DUB: Dublin, ECO: Escherichia coli, ENT: Enteritidis, HEI: Heidelberg, JAV: Javiana, KEN: Kentucky, MBA: Mbandaka, MON: Montevideo, MUE: Muenster, NEW: Newport, ORA: Oranienburg, PAN: Panama, SAI: Saintpaul, STA: Stanley, TYP: Typhimurium, VIR: Virchow, WEL: Weltevreden.

Overall, PFGE analysis of phage genomes (for all phage isolates except the two co-cultures) allowed for classification of phages into eleven groups, including (i) phages with genome sizes of 22, 40, 48, 56, 62, 72, 86, and 156 kb as well as (ii) phages with cohesive ends and genome sizes of 22, 40 and 60 kb (Table 4). Each genomic size group contained phage isolates representing multiple lysis groups and host ranges (see Table 4), while only two lysis profiles (i.e., LP40 and LP60) included phages with different genome sizes. For example, LP60 included phages with 5 different genome sizes. We also identified a number of instances where multiple phage isolates represent the same lysis profile and genome size, including 5 instances where phages with the same lysis profile and genome size represented isolates from different farms. For examples, all 17 phages that only lysed S. Cerro and classified into LP21 had a genome size of 40 kb (Table 4, Fig. 1). For three phages representing three lysis profiles (LP29, LP34, and LP44; Table 4), nucleic acids reproducibly presented no band on PFGE (despite OD260 readings that indicated the presence of sufficient DNA) and a nucleic acid “smear” when characterized by regular agarose gel electrophoresis; these phages may have single stranded genomes and were not further characterized.

Three phages, representing 22 Kb (SP-004), 56 Kb (SP-062), and 72 Kb (SP-076), were selected for characterization by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). These three phages were classified into three known families of Caudovirales. Specifically, SP-004 was classified as a Myoviridae phage with a contractile tail, SP-062 was classified as a Syphoviridae phage with a long non-contractile tail, and SP-076 was classified as a Podoviridae phage with a short tail (Suppl. Fig. 2).

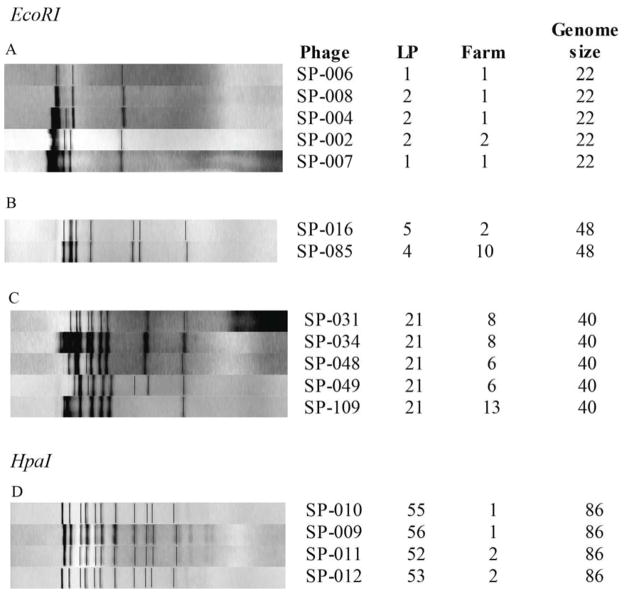

3.4. Restriction pattern analysis

A total of 55 phage isolates representing groups of isolates with identical genome sizes and identical or similar lysis profiles isolated from different farms were initially characterized using genomic EcoRI restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. While 47 phages were readily digested with EcoRI, eight phages (five phages of 86 kb and three of 156 kb) were resistant to EcoRI digestion, suggesting DNA modifications in these phages. Among five additional enzymes tested (i.e., RsaI, KpaI, HpaI, PsaI, and SalI), only HpaI digested the genomes of these eight phages. EcoRI patterns ranged from three to >15 bands (see Suppl. Fig. 3) and allowed for good discrimination. For phage isolates with a genome sizes of 62, 72, and 156 kb each isolate tested (i.e., 8, 4, and 2, isolates, respectively) showed a different EcoRI RFLP pattern. The 9, 11, and 10 phage isolates with genome sizes of 22, 40, and 56 kb were differentiated into 6, 10, and 7 EcoRI RFLP patterns (see Suppl. Fig 3). Overall, restriction patterns were difficult to interpret for some phages though (e.g., due to a large numbers of bands with similar sizes, particularly for phages with larger genomes). We thus used RFLP data to specifically analyze phages with identical genome sizes and identical or similar lysis profiles, differentiating them into closely related phages (phages with identical or very similar RFLP pattern) and distinct phages (phages with different banding pattern), as discussed in detail below.

The nine phage isolates with a 22 kb genome represented six different EcoRI restriction profiles (Suppl. Fig. 3). Five phage isolates with a 22 kb genome isolated from farms 1 and 2 (located in separate counties in New York) and representing two wide host range LP (LP1 and LP2), were differentiated into two similar EcoRI patterns, which differed by a single band (Fig. 2a), suggesting that small genetic differences may have influenced the host range of these strains. While all five of these phages showed lysis of E. coli and three Salmonella serovars (Newport, 4,5,12:i:-, and Infantis), the three LP2 phage isolates also lysed Montevideo, Oranienburg, and Agona. One of these EcoRI RFLP pattern represented one phage with LP1 obtained from farm 1 and one phage with LP2 obtained from farm 2 (Fig. 2a). The three other phage isolates, which all represented a closely related EcoRI pattern, were classified into two lysis profiles (LP1 and LP2) and were all isolated from farm 1. We also identified two phage isolates with a 48 kb genome, representing LP4 and LP5 and isolated from farms 2 and 10 (separated by 51 km), that showed highly similar EcoRI RFLP patterns (Fig. 2b and Table 4); these phages differed in their ability to lyse three Salmonella serovars. Similarly, four phage isolates with a 86 kb genome, representing four lysis profiles (LP52, LP53, LP55, and LP56), showed identical HpaI RFLP patterns (Fig. 2d); two of these phage isolates were obtained from each farm 1 and 2. Among the phage isolates with 40 kb genomes, phage isolates with LP21 (which only showed lysis with serovar Cerro) were found on three farms; the isolates from these farms showed similar but not identical restriction patterns (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2. EcoRI and HpaI restriction pattern for representative phage isolates.

Patterns shown represent instances where phage isolates with similar or identical RFLP profiles, host ranges, and genome sizes were isolated from multiple farms (RFLP profiles for all phages characterized are shown in Suppl. Fig. 3 and 4). Patterns were normalized with Bionumerics and the figure shows both the normalized RFLP pattern as well as the bands identified (shown as thin black lines). Panels A to C show three groups of phages with similar EcoRI restriction patterns; panel D shows a group of phages with similar HpaI restriction patterns (D).

4. Discussion

To enhance our understanding of the ecology and diversity of Salmonella bacteriophages, we isolated, purified, and characterized Salmonella phages from samples collected on dairy farms with a history of Salmonella isolation from environmental samples and animals without clinical signs. Our data indicated that (i) Salmonella phages are common and widely distributed on dairy farms with a history of Salmonella isolation; (ii) Salmonella phage isolates from dairy farms represent considerable phenotypic and genetic diversity, including narrow and wide host range lysis profiles; and (iii) many of the Salmonella phages isolated on dairy farms lyse Salmonella serovars associated with bovine and human salmonellosis.

4.1. Salmonella phages are common and widely distributed on dairy farms with a history of Salmonella isolation

Our samples showed a high frequency of Salmonella phage isolation, with 78% of samples collected from the manure storage and animal holding areas yielding phage isolates, including a large number of samples that yielded phage isolates with multiple distinct lysis profiles. While some previous studies have reported isolation of Salmonella phages from fecal samples collected from multiple hosts (i.e., humans, swine, and cattle), these previous studies have found lower frequency of Salmonella phage isolation from bovine fecal samples (i.e., 0–18%) (López-Cuevas et al., 2011; O’Flynn et al., 2006) as compared to a frequency of phage isolation of up to 81% from swine and poultry fecal samples (Andreatti Filho et al., 2007; Callaway et al., 2011; Hooton et al., 2011a; Wang et al., 2010). While these previous studies have used individual fecal samples, our study here used samples that represent natural pools of feces from animals on a given farm. In addition, samples collected in our study here were obtained from farms with a history of Salmonella isolation. Our study also used multiple Salmonella host strains focusing on serovars commonly associated with bovine hosts, while some of these previous studies used a single host and/or Salmonella host strains that may be less common among cattle (e.g., serovar Enteritidis (Higgins et al., 2005)). While all of these factors may have contributed to the high frequency of Salmonella phage isolation among the samples collected here, our data clearly suggest that high frequency isolation of phages is possible when testing pooled manure samples from bovine farms with a history of Salmonella presence, using host strains that are commonly found in cattle.

Similar to our study, previous studies have also shown frequent isolation of E. coli O157:H7 phages from fecal samples collected from feedlot and dairy cattle (Bicalho et al., 2010; Oot et al., 2007). Overall, the apparent high prevalence of free-living phages infecting different cattle-associated foodborne pathogens, including Salmonella and E. coli O157:H7, not only suggests an important role of phages in the ecology and distribution of these important foodborne pathogens (Casjens, 2005; Oot et al., 2007), but also suggests that cattle may represent an important source of phage isolates, which could be used for the development of novel control strategies and detection methods for these pathogens.

4.2. Salmonella phage isolates from dairy farms represent considerable phenotypic and genetic diversity

The Salmonella bacteriophage isolates obtained here were characterized by considerable biodiversity, with 65 different lysis profile and large genetic heterogeneity, represented by different genome sizes and RFLP patterns, among the 108 phage isolates analyzed in this study. Classification of phage isolates into different lysis groups does not necessarily imply though that these are distinct phages as minor variants of the same phage can represent different host ranges. While a final assessment of the phage diversity will require more comprehensive molecular characterization of these isolates, e.g., through genome sequencing, as well as possibly EM-based classification of additional phage isolates, our data provide important initial insights into Salmonella phage diversity on dairy farms. The considerable lysis profile and genome size diversity observed here is particularly noteworthy as we restricted our analysis to two samples per farm. Our findings are consistent with previous studies, including one study (Stenholm et al., 2008), which isolated, from a relatively small number of samples, a considerable diversity of phages lysing the fish pathogen Flavobacterium psychrophilum, as supported by identification of 18 lysis profiles among 22 phages isolated from 31 water samples. Similarly, two studies found considerable host range diversity among Salmonella phages isolated from swine effluent lagoons and poultry (Atterbury et al., 2007; McLaughlin and King, 2008); 232 phages obtained in one study (Atterbury et al., 2007) represented 80 different lysis profiles.

Despite the diversity of phages found here as well as in other studies (Atterbury et al., 2007; McLaughlin et al., 2006; Stenholm et al., 2008), we also identified phage isolates with very similar lysis profiles and genotypic characteristics (genome size and RFLP) on different, geographically separated farms. For example, farms 1 and 2, which are approximately 65 km apart, shared two different types of phages with each with identical RFLP profiles and host ranges. These findings may indicate a connection between these two farms, such as a common source of feed, animals, or exchange of vectors (e.g., insects, rodents, birds) (Pangloli et al., 2008). Similar findings have been reported though in oceanic ecosystems where genetically related phages have been found over thousands of kilometers apart, a concept known as “long-distance” phage host systems (Holmfeldt et al., 2007; Kellogg et al., 1995). Similar data have also been reported for terrestrial ecosystems where similar phages infecting Actinoplanes were found to be widely distributed and isolated from sources located more than 600 km apart (Jarling et al., 2004). While these observations suggest efficient long range passive dispersal of phages (Thurber, 2009), relatively slow diversification through genome rearrangements, at least in some phages, may also contribute to these observations.

4.3. Phages infecting the most common serovars of Salmonella associated with bovine and human salmonellosis are commonly isolated on dairy farms

The largest number of phage isolates obtained in this study was isolated on a Salmonella Newport host strain. In addition, strains representing serovars Newport, Cerro, and 4,5,12:i:- were most frequently lysed by the phage isolates collected here. Interestingly, these three serovars are currently among the predominant serovars isolated from cattle in New York (Hoelzer et al., 2011a; CDC, 2009; Van Kessel et al., 2011). Given previous observations that phage-induced mortality represents an important factor in prokaryotic mortality in aquatic systems (Weinbauer and Rassoulzadegan, 2004) and the large number of lytic S. Newport and S. Cerro phages detected in this study, it appears likely that these phages may facilitate turnover of Salmonella Newport and Cerro populations on dairy farms. Consistent with this hypothesis, a recent study (Van Kessel et al., 2012) reported shifts in Salmonella serovar prevalence on a dairy farm, including apparent replacement of Salmonella Cerro, which persisted over 3 years, by Salmonella Kentucky.

Interestingly, we also found that narrow host range phages appeared to be preferentially isolated from farms with high Salmonella prevalence, suggesting a relation between host density and niche specialization. On three of the five farms with a high Salmonella prevalence, serovar Cerro was frequently isolated, consistent with previous reports that serovar Cerro was often present on dairy farms with a high prevalence, based on sampling in 2008 and 2009 (Cummings et al., 2010). On all three of these farms we obtained phage isolates that only lysed Salmonella Cerro; on two of these farms we also found high levels of Salmonella phages (up to 1.5×104 PFU/g) when phage enumeration was performed on a Cerro host. Similar to our observations, one previous study also reported that phages collected from higher host density waters are characterized by greater host specialization (Guyader and Burch, 2008). These results agree with predator-prey models, which predict predator specialization on profitable prey unless the prey numbers are low (Guyader and Burch, 2008). On the other hand, the frequent isolation of phages on Salmonella Cerro hosts could indicate that this serovar is highly susceptible to phages; however, we are not aware of any data that would suggest S. Cerro features that could be linked to a high phage susceptibility. In addition, S. Cerro was mostly susceptible to phages isolated from farms where this serovar was abundant, which suggests selection of phages that infect S. Cerro in environments where this serovar is abundant, rather than an intrinsic phage susceptibility of this serovar.

While some serovars used in the host range characterization reported here were lysed by a large proportion of phages, other serovars appeared to be rarely lysed by the phages isolated here. For example, four of the seven strains used as host for phage isolation (i.e., isolates representing serovars Newport, Cerro, Dublin and Typhimurium) were among the five strains that were most frequently lysed by our phages. While one might surmise that this is a reflection of that fact that we selected for phages infecting these serovars, serovar Kentucky, which was also used for phage isolation for all farms, yielded fewer phages when used as host and was lysed by fewer phages in the host range experiments as compared to serovars Newport, Cerro, Dublin and Typhimurium. Serovar Kentucky was, however, the most commonly isolated Salmonella serovar from dairy farms in upstate New York during parts of 2008 (Hoelzer et al., 2010) and represented the predominant serovar on three farms included here (these farms showed 9–13% prevalence for serovar Kentucky); even on these farms we did not isolate phages infecting serovar Kentucky. These results could reflect that selection for phages that infect serovar Kentucky has not yet occurred on these farms, may simply reflect the fact that we did not sample the full phage diversity, or could indicate that serovar Kentucky is intrinsically insensitive to most phages (as shown for serovar Anatum, where phage resistance appears to be mediated by a serovar-specific smooth lipopolysaccharide (McConnell and Wright, 1979)). While future studies will be needed to further address these questions, our data do suggest considerable differences in the prevalence of phage isolates that lyse different Salmonella serovars associated with dairy farms, which supports a potential role for bacteriophages in shaping the Salmonella serovar diversity in pre-harvest environments.

5. Conclusion

This study represents a comprehensive study on Salmonella phage diversity on dairy farms. Our data not only suggest that Salmonella phages are common in the dairy pre524 harvest environment, but also suggest that phages can affect and shape the diversity of Salmonella and other pathogens found. In addition, our study suggests that samples collected on dairy farms, particularly those with a history of animal infections with Salmonella, may provide a good source for isolation of diverse Salmonella phages with the potential to be used for the development of novel Salmonella detection and control strategies. The phage isolates described here also represent a valuable resource for further taxonomic and genomic studies of Salmonella bacteriophages.

Supplementary Material

List of all Salmonella phage isolates including their sources and relevant characteristics.

Bacteriophage host range. Figure shows the number of phage isolates that lysed a given number of the 26 tested host strains.

Transmission Electron microscopy (TEM). Three phages with different genome sizes were selected for TEM, specifically, SP-004 (22 Kb), SP-(56 Kb), and SP-076 (72 Kb). TEM and sample preparation were conducted at the Cornell Center for Materials Research. Lysates were stained with 2% of uranyl acetate. Images were capture with a FEI Tecnai T-12 TWIN TEM. The three families of Caudovirales were identified (a) Phage SP-004 has a contractile tail indicating that represents Myoviridae, (b) phage SP-062 has a long non-contractile tail indicating that represents Siphoviridae, and (c) phage SP-076 has a short tail indicating that represents Podoviridae.

EcoRI RFLP patterns for 47 selected phage isolates. Phage isolate ID is shown on the right hand side (e.g., SP-006).

HpaI RFLP patterns for 8 phage isolates that could not be restricted by EcoRI. Phage isolate ID is shown on the right hand side (e.g., SP-011).

Highlights.

We isolated 108 Salmonella phages from dairy farms with history of Salmonella isolation

We found high diversity of phages, represented by 65 different lysis profiles found among the 108 phage isolates

In farms with high Salmonella prevalence, specialized phages were commonly isolated

Phages lysing the most common Salmonella serovars causing human and bovine salmonellosis were commonly isolated from the dairy farms sampled

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Joseph Peters for his helpful contributions in bacteriophage knowledge. We also thank Thomas Denes for kindly reading the manuscript. Finally, we thank Felix d’Herelle Collection, Laval University, Quebec, Canada for providing the control phage Felix 01. Support for this project was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. N01-AI-30054 (to Lorin Warnick). The funding source had not role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andreatti Filho RL, Higgins JP, Higgins SE, Gaona G, Wolfenden AD, Tellez G, Hargis BM. Ability of bacteriophages isolated from different sources to reduce Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis in vitro and in vivo. Poultry Sci. 2007;86(9):1904–9. doi: 10.1093/ps/86.9.1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atterbury RJ, Van Bergen MA, Ortiz F, Lovell MA, Harris JA, De Boer A, Wagenaar JA, et al. Bacteriophage therapy to reduce Salmonella colonization of broiler chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(14):4543–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00049-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicalho RC, Santos TM, Gilbert RO, Caixeta LS, Teixeira LM, Bicalho ML, Machado VS. Susceptibility of Escherichia coli isolated from uteri of postpartum dairy cows to antibiotic and environmental bacteriophages. Part I: Isolation and lytic activity estimation of bacteriophages. J Dairy Sci. 2010;93(1):93–104. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielke L, Higgins S, Donoghue A, Donoghue D, Hargis BM. Salmonella host range of bacteriophages that infect multiple genera. Poultry Sci. 2007;86(12):2536–40. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway TR, Keen JE, Edrington TS, Baumgard LH, Spicer L, Fonda ES, Griswold KE, et al. Fecal prevalence and diversity of Salmonella species in lactating dairy cattle in four states. J Dairy Sci. 2005;88(10):3603–8. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)73045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway TR, Edrington TS, Brabban A, Kutter E, Karriker L, Stahl C, Wagstrom E, et al. Occurrence of Salmonella-specific bacteriophages in swine feces collected from commercial farms. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2010;7(7):851–6. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway TR, Edrington TS, Brabban A, Kutter B, Karriker L, Stahl C, Wagstrom E, et al. Evaluation of phage treatment as a strategy to reduce Salmonella populations in growing swine. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011;8(2):261–6. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens SR. Comparative genomics and evolution of the tailed-bacteriophages. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8(4):451–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens SR. Diversity among the tailed-bacteriophages that infect the Enterobacteriaceae. Res Microbiol. 2008;159(5):340–8. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [CDC] Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Salmonella: annual summary (2008) Vol. 2006. Atlanta, GA: CDC, Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases; 2008. [accessed on 05/28/2013]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dfwed/PDFs/SalmonellaAnnualSummaryTables2008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [CDC] Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Salmonella: annual summary (2009) Vol. 2007. Atlanta, GA: CDC, Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases; 2009. [accessed on 05/28/2013]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dfwed/PDFs/SalmonellaAnnualSummaryTables2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings KJ, Warnick LD, Elton M, Gröhn YT, McDonough PL, Siler JD. The effect of clinical outbreaks of salmonellosis on the prevalence of fecal Salmonella shedding among dairy cattle in New York. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2010;7(7):815–23. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruque SM, Naser IB, Islam MJ, Faruque AS, Ghosh AN, Nair GB, Sack DA, et al. Seasonal epidemics of cholera inversely correlate with the prevalence of environmental cholera phages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(5):1702–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408992102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley SL, Nayak R, Hanning IB, Johnson TJ, Han J, Ricke SC. Population dynamics of Salmonella enterica serotypes in commercial egg and poultry production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(13):4273–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00598-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanis E, Lo Fo Wong DM, Patrick ME, Binsztein N, Cieslik A, Chalermchikit T, Aidara-Kane A, et al. Web-based surveillance and global Salmonella distribution, 2000–2002. Emerg Infec Dis. 2006;12(3):381–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1203.050854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyader S, Burch CL. Optimal foraging predicts the ecology but not the evolution of host specialization in bacteriophages. PloS one. 2008;3(4):e1946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Higgins SE, Guenther KL, Huff W, Donoghue AM, Donoghue DJ, Hargis BM. Use of a specific bacteriophage treatment to reduce Salmonella in poultry products. Poultry Sci. 2005;84(7):1141–5. doi: 10.1093/ps/84.7.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelzer K, Soyer Y, Rodriguez-Rivera LD, Cummings KJ, McDonough PL, Schoonmaker-Bopp DJ, Root TP, et al. The prevalence of multidrug resistance is higher among bovine than human Salmonella enterica serotype Newport, Typhimurium, and 4,5,12:i:- isolates in the United States but differs by serotype and geographic region. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(17):5947–59. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00377-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelzer K, Cummings KJ, Wright EM, Rodriguez-Rivera LD, Roof SE, Moreno Switt AI, Dumas N, et al. Salmonella Cerro isolated over the past twenty years from various sources in the US represent a single predominant pulsed-field gel electrophoresis type. Vet Microbiol. 2011a;150(3–4):389–93. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelzer Karin, Moreno Switt AI, Wiedmann M. Animal contact as a source of human non-typhoidal salmonellosis. Vet Res. 2011b;42(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-42-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmfeldt K, Middelboe M, Nybroe O, Riemann L. Large variabilities in host strain susceptibility and phage host range govern interactions between lytic marine phages and their Flavobacterium hosts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(21):6730–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01399-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooton SP, Atterbury RJ, Connerton IF. Application of a bacteriophage cocktail to reduce Salmonella Typhimurium U288 contamination on pig skin. Int J Food Microbiol. 2011a;151(2):157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooton SP, Timms AR, Rowsell J, Wilson R, Connerton IF. Salmonella Typhimurium-specific bacteriophage ΦSH19 and the origins of species specificity in the Vi01-like phage family. Virol J. 2011b;8:498. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamovic L, Muniesa M. Quantification and evaluation of infectivity of shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages in beef and salad. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(10):3536–40. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02703-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarling M, Bartkowiak K, Robenek H, Pape H, Meinhardt F. Isolation of phages infecting Actinoplanes SN223 and characterization of two of these viruses. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;64(2):250–4. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1473-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg C, Rose J, Jiang S, Thurmond J, Paul J. Genetic diversity of related vibriophages isolated from marine environments around Florida and Hawaii, USA. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1995;120(1–3):89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Klumpp J, Dorscht J, Lurz R, Bielmann R, Wieland M, Zimmer M, Calendar R, et al. The terminally redundant, nonpermuted genome of Listeria bacteriophage A511: a model for the SPO1-like myoviruses of gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(17):5753–65. doi: 10.1128/JB.00461-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropinski AM, Sulakvelidze A, Konczy P, Poppe C. Salmonella phages and prophages--genomics and practical aspects. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;394:133–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-512-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Shin H, Kim H, Ryu S. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella bacteriophage SPN3US. J Virol. 2011;85(24):13470–1. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06344-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Shin H, Ryu S. Complete Genome Sequence of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Bacteriophage SPN3UB. J Virol. 2012;86(6):3404–5. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07226-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Cuevas O, Castro-Del Campo N, León-Félix J, González-Robles A, Chaidez C. Characterization of bacteriophages with a lytic effect on various Salmonella serotypes and Escherichia coli O157:H7. Can J Microbiol. 2011;57(12):1042–51. doi: 10.1139/w11-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell M, Wright A. Variation in the structure and bacteriophage644 inactivating capacity of Salmonella Anatum lipopolysaccharide as a function of growth temperature. J Bacteriol. 1979;137(2):746–51. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.2.746-751.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin MR, Balaa MF, Sims J, King R. Isolation of Salmonella bacteriophages from swine effluent lagoons. J Environ Qual. 2006;35(2):522–8. doi: 10.2134/jeq2005.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin MR, King RA. Characterization of Salmonella bacteriophages isolated from swine lagoon effluent. Curr Microbiol. 2008;56(3):208–13. doi: 10.1007/s00284-007-9057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniesa M, Serra-Moreno R, Jofre J. Free Shiga toxin bacteriophages isolated from sewage showed diversity although the stx genes appeared conserved. Environ Microbiol. 2004;6(7):716–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murase T, Nagato M, Shirota K, Katoh H, Otsuki K. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis-based subtyping of DNA degradation-sensitive Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Livingstone and serovar Cerro isolates obtained from a chicken layer farm. Vet Microbiol. 2004;99(2):139–43. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Flynn G, Coffey A, Fitzgerald GF, Ross RP. The newly isolated lytic bacteriophages st104a and st104b are highly virulent against Salmonella enterica. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;101(1):251–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oot RA, Raya RR, Callaway TR, Edrington TS, Kutter EM, Brabban AD. Prevalence of Escherichia coli O157 and O157:H7-infecting bacteriophages in feedlot cattle feces. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2007;45(4):445–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangloli P, Dje Y, Ahmed O, Doane CA, Oliver SP, Draughon FA. Seasonal incidence and molecular characterization of Salmonella from dairy cows, calves, and farm environment. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2008;5(1):87–96. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2008.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard D, Toribio AL, Petty NK, Van Tonder A, Yu L, Goulding D, Barrell B, et al. A conserved acetyl esterase domain targets diverse bacteriophages to the Vi capsular receptor of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(21):5746–54. doi: 10.1128/JB.00659-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning. 3. 1–3. Cold Spring Habour Laboratory Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States--major pathogens. Emerg Infec Dis. 2011;17(1):7–15. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.P11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenholm AR, Dalsgaard I, Middelboe M. Isolation and characterization of bacteriophages infecting the fish pathogen Flavobacterium psychrophilum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(13):4070–8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00428-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurber RV. Current insights into phage biodiversity and biogeography. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;5:582–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA/APHIS. [accessed May 28, 2013];Subject: Salmonella and Campylobacter on U.S. Dairy Operations. 2003 Available at: http://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/dairy/downloads/dairy02/Dairy02_is_SalCampy.pdf.

- Van Kessel JS, Karns JS, Wolfgang DR, Hovingh E, Jayarao BM, Van Tassell CP, Schukken YH. Environmental sampling to predict fecal prevalence of Salmonella in an intensively monitored dairy herd. J Food Prot. 2008;71(10):1967–73. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-71.10.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kessel JS, Karns JS, Lombard JE, Kopral CA. Prevalence of Salmonella enterica, Listeria monocytogenes, and Escherichia coli virulence factors in bulk tank milk and in-line filters from U.S. dairies. J Food Prot. 2011;74(5):759–68. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-10-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kessel JS, Karns JS, Wolfgang DR, Hovingh E, Schukken YH. Dynamics of Salmonella serotype shifts in an endemically infected dairy herd. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2012;9(4):319–24. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Zhao W, Raza A, Friendship R, Johnson R, Kostrzynska M, Warriner K. Prevalence of Salmonella infecting bacteriophages associated with Ontario pig farms and the holding area of a high capacity pork processing facility. J Sci Food Agric. 2010;90(13):2318–25. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinbauer MG, Rassoulzadegan F. Are viruses driving microbial diversification and diversity? Environ Microbiol. 2004;6(1):1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whichard JM, Weigt LA, Borris DJ, Li LL, Zhang Q, Kapur V, Pierson FW, et al. Complete genomic sequence of bacteriophage felix o1. Viruses. 2010;2(3):710–30. doi: 10.3390/v2030710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of all Salmonella phage isolates including their sources and relevant characteristics.

Bacteriophage host range. Figure shows the number of phage isolates that lysed a given number of the 26 tested host strains.

Transmission Electron microscopy (TEM). Three phages with different genome sizes were selected for TEM, specifically, SP-004 (22 Kb), SP-(56 Kb), and SP-076 (72 Kb). TEM and sample preparation were conducted at the Cornell Center for Materials Research. Lysates were stained with 2% of uranyl acetate. Images were capture with a FEI Tecnai T-12 TWIN TEM. The three families of Caudovirales were identified (a) Phage SP-004 has a contractile tail indicating that represents Myoviridae, (b) phage SP-062 has a long non-contractile tail indicating that represents Siphoviridae, and (c) phage SP-076 has a short tail indicating that represents Podoviridae.

EcoRI RFLP patterns for 47 selected phage isolates. Phage isolate ID is shown on the right hand side (e.g., SP-006).

HpaI RFLP patterns for 8 phage isolates that could not be restricted by EcoRI. Phage isolate ID is shown on the right hand side (e.g., SP-011).