Abstract

Indicator dilution experiments were done to determine the extraction of 85Sr during a single passage through capillaries of the tibial diaphysis. Extraction was estimated by injection of 85SrCl2 and a nonpermeant, reference tracer, T-1824-labeled albumin, into the nutrient artery and recording of the effluent venous dilution curves (femoral vein). The mean (± SD) maximal instantaneous extraction was 0.53 ± 0.08 (N = 12). Net retention after 10 min, estimated from venous curves, was 0.41 ± 0.06 (N = 12), which appeared not substantially different from the retention estimated by direct isotope counting of the tibias for 85Sr, 0.35 ± 0.06 (N = 12). In a second set of experiments in intact animals, tibial 85Sr extraction after intravenous injection was apparently higher, 0.53 ± 0.28 (N = 15). Values of tibial diaphyseal blood flow, estimated from washout curves for iodoantipyrine after tibial nutrient artery injection, were 1.47 ± 0.63 ml/min per 100 g (N = 27). The extraction was not much diminished by higher flows. The estimates of permeability-surface area product (PS) for bone capillaries did increase with flow, suggesting recruitment of more capillaries at higher flows. PS values averaged 0.63 ± 0.29 (N = 12); we conclude that the capillary membrane is a primary barrier to the passage of 85Sr and presumably other small hydrophilic solutes.

Keywords: bone blood flow, instantaneous extraction, permeability-surface area products, 85Sr clearance, diffusible and nondiffusible tracers, bone capillary permeability, calcium uptake mechanisms in bone

Strontium, being after calcium in the series of divalent cations in the periodic table, behaves very similarly to it in a wide variety of biologic situations. Because 85Sr has a readily detectable γ-emission and has stable fission products, unlike 47Ca, it is very useful in measuring the processes of uptake, deposition, and exchange in bone.

In this study, we focused our attention on the first stage of the uptake process, the extraction of Sr2+ from blood as it passes through the circulation of the bone. Previous work in other organs (e.g., 3, 8) has shown that the capillary endothelial lining membrane can be the primary barrier to escape of tracers from the blood and that, when this is so, the extraction during a single transcapillary passage is incomplete. We (2, 8) and others have worked out the theory and application of a technique for measuring the instant-by-instant extraction of a permeating tracer by comparing its concentration in the venous outflow with that of a nonpenetrating reference tracer. From this extraction, one can estimate the overall conductance of the barrier, its permeability-surface area product (PS), when one knows the flow

| (1) |

in which P is permeability (cm/min), S is surface area (cm2/100 g of organ), Fs is the flow of solute carrying mother fluid (ml/min per 100 g), and E is the pertinent instantaneous fractional extraction. For Sr in these experiments, Fs is the plasma flow, which is (1 – Hct) times the blood flow.

This approach is based on obtaining an instantaneous extraction value, E, which is a measure of the unidirectional flux of Sr from blood to tissue. It will be compared with other methods that give values in proportion to the net flux or net uptake of Sr. These are based on the average extraction of 85Sr, over several minutes, relative to a nonpermeant tracer, an average arteriovenous difference for 85Sr over a 10-min period, and the fractional recovery of the 85Sr accumulated in bone over a 10-min period.

Methods And Materials

Adult, nonanemic, male, mongrel dogs weighing between 16 and 30 kg were fasted overnight, anesthetized with intravenous sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg), and anticoagulated with aqueous sodium heparin (1,250 USP units).

General Design of Experiments

The instantaneous Sr extraction and tibial blood flow were estimated in one group of animals. A transfibular approach was used to expose, isolate, and cannulate the tibial nutrient artery. Tibial blood flow was estimated from an 131I-labeled iodoantipyrine (IAp) washout curve over a 15-min period (see below). Then, the femoral vein was cannulated. To maximize the return of venous blood into this cannula, the deep femoral vein was ligated and a 5-cm-wide cuff was placed around the thigh just proximal to the distal end of the cannula and inflated to 60–80 mmHg to block venous return from the leg to the dog by other channels, following the approach used by Bosch (4). In two dogs, the inflated cuff caused no detectable changes in distal femoral artery pressures. Then 85Sr and T-1824-labeled albumin were injected into the nutrient artery; the resultant indicator dilution curves were obtained by sampling from the femoral vein for the estimation of both the instantaneous extraction and the average or integral net extraction; the fraction of the tracer remaining in the tibia was estimated by gamma counting of the bone.

Tibial net extraction of Sr (calculated from arteriovenous concentration differences and tibial blood flow) was measured in another 15 dogs prepared similarly. After isolation of the tibial nutrient artery and vein, tibial blood flow was estimated by IAp residue washout after injection into the nutrient artery. After cannulation of the carotid artery and jugular vein and waiting 45 min for IAp distribution and dilution in body water space, 85Sr (10 μCi) was injected into the jugular vein and the average arteriovenous difference for 85Sr across the tibia during the subsequent 10 min was determined. Arterial blood samples were withdrawn from the carotid artery at 1-min intervals for 10 min; during this same 10-min period, blood was continuously collected from the tibial nutrient vein. At the end of this 10-min period, the dog was killed by intravenous injection of pentobarbital, and the tibia was immediately disarticulated and cleaned of all soft tissue. The whole tibia and, subsequently, large diaphyseal segments (10–11 cm long, essentially the entire diaphysis) with and without marrow were weighed and counted with a standard in a small whole-animal counting chamber. The data provided arterial clearance curves for 85Sr, average arteriovenous difference and net extraction, and tibial 10-min accumulation.

Tracers

For instantaneous Sr extraction studies, 5 μCi of 85SrCl2 (Stronscan-85, Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, I11.) were injected with 0.5 ml of 0.5 % aqueous Evans blue solution (T-1824, Warner Chilcott, Morris Plains, N. J.) added to 0.75 ml of the dog's plasma to ensure binding of T-1824 to albumin (13). Intravascular retention of T-1824 allows its use as a nonextracted reference marker. For the net arteriovenous extraction studies, 10 μCi of 85SrCl2 alone were injected. For tibial blood flow estimation, we used 14 μCi of 131I-labeled 4-iodoantipyrine (IAp) (Abbott Laboratories).

Estimation of Tibial Blood Flow by IAp Washout

The technique has been reported in detail (10) but will be summarized here. IAp in saline (14 μCi in 1 ml) was injected over 3–5 s into the tibial nutrient artery. The IAp residue function, the washout curve, was obtained over a 15-min period via a gamma-sensitive NaI (T1-activated) crystal detector positioned over the anteromedial diaphyseal area of the tibia. It was recorded on an analog rate meter, providing the count rate, C*(t), as a function of time, t.

The tibial diaphyseal blood flow was estimated from the curve by using a modification of the height/area method of Zierler (10, 22)

| (2) |

in which R(t) is the residue function (the radioactivity C*(t) measured by an external detector at time, t, divided by the activity C*(0) at the initial peak after the injection), λb is the bone-blood partition coefficeint, ρb is bone density (g/ml), and FIAp is the blood flow in ml/min per 100 g of tissue (bone + marrow). The formula assumes either equal counting efficiency for bone and marrow, which is required if their capillary beds are in parallel, or that their capillary beds are in series, in which case their relative efficiencies do not matter. T is the time of the end of the recording—in these studies, 15 min. The integral in the denominator is the area under the washout curve. The partition coefficient for the total bone is the weighted average

in which V is volume (ml) and w is weight (g) of cortex (subscript c) and of marrow (subscript m). Similarly, the average bone density was calculated by

For cortical bone, the partition coefficient λc is 0.15 ± 0.027 ml/ml (10); for marrow, λm is 0.62 ± 0.16 ml/ml (9). Density values were 1.94 ± 0.1 g/ml for ρc (10) and 0.94 g/ml for ρm (1). λb/ρb was calculated from these values and the individual values for wc and wm measured in each experiment.

Estimation of Strontium Extractions

Instant-by-instant extractions

After nutrient artery injection of 85Sr and T-1824, concentration-vs.-time curves were obtained from the tibial venous outflow. To ensure that all tracer effluent from the bone was sampled, instead of nutrient vein samples we used femoral vein samples because in these the ratios of 85Sr and T-1824 concentrations would not be changed by dilution with blood coming from tissues other than the tibia but sample volumes would be large and there would be no risk of disturbing the tibial outflow. An intravenous infusion of electrolyte solution was started proximal to the cannulation site in the femoral vein to maintain circulatory volume. The femoral vein cannula was opened and the control blood sample was obtained. After approximately 2 min, the flow from the femoral vein stabilized. The prepared injectate, with a volume of 1.45 ml, was then introduced into the tibial nutrient artery over a 1.5-min period, rather than instantaneously, so as not to create an artificially high flow in the bone vascular space. After the injection was started, blood was collected from the femoral vein at 30-s intervals for the first 3 min and then at 1-min intervals for 7 min.

Individual sample volumes and hematocrit values were measured, and aliquots of plasma were removed for counting of 85Sr in the well scintillation counter and for spectro-photometric measurement of Evans blue concentration. By using a standard and correcting for plasma volume changes on the basis of serial hematocrit values, the concentrations in blood of 85Sr (CSr, in counts/min) and of the reference, nonpermeant, T-1824 (CN, in mg/liter) in 1-ml samples from the femoral vein were determined. Normalized concentration-vs.-time curves (fraction of dose per minute) were calculated as follows, Ffv representing flow at the femoral vein sampling site

| (3) |

| (4) |

From these, the instantaneous strontium extraction, E(t), was calculated

| (5) |

The maximal value of E(t) is Emax, which is taken to be the best measure of instantaneous extraction in a tissue with heterogenous flow (2).

Net extraction

The concurrent injection of these tracers also allowed the calculation of an average net Sr extraction [Enet(t)] up to any particular time, t

| (6) |

For purposes of comparison with the measured residue, the values were taken along to time t = T, the time of stopping the circulation (in this set of experiments, T = 10 min).

Tibial Residual Content

At the end of the 10-min period, the dog was killed and the tibia was disarticulated and cleaned of soft tissue. The whole bone was counted for 85Sr in the small whole-animal counting chamber, giving the fractional residue at the end of 10 min

| (7) |

The fractional recovery of the initial 85Sr dose was obtained by summing the amount retained in the tibia and the amount collected at the femoral vein over the 10-min study period. This was corrected for the amount of unrecovered T-1824 on the basis that the ratio of Sr to T-1824 would be the same in the femoral vein blood as in un-sampled collaterals so that

| (8) |

A-V Extraction in Tibial Diaphysis

The mean tibial extraction of 85Sr over the 10-min period after 85SrCl2 injection into the jugular vein was obtained from the average arteriovenous concentration differences

| (9) |

The blood samples from the carotid artery and tibial nutrient vein were counted with a standard in a well scintillation counter. CA (counts/min per ml blood) was taken as the mean of the 10 carotid samples taken at 1-min intervals. CNV was the concentration (counts/min per ml blood) in the single 10-min-long nutrient vein sample.

Clearance

The tibial Sr clearance, ClSr, was also calculated by using the 85Sr content of the bone (cortex and marrow) at T = 10 min

| (10) |

The clearance by specific components of bone—diaphysis, cortex, or marrow—could be calculated by using the pertinent residual tissue concentration, C*Sr. These data permit a test of the use of tibial Sr clearance as a measure of tibial blood flow.

Results

Estimates of Tibial Blood Flow

The residue function curves gave a mean (± SD) value of FIAp of 1.47 ± 0.63 ml/min per 100 g (N = 27, which included both sets of experiments since there was no experimental or statistical difference). Each estimate of FIAp by Eq. 2 required the calculation of λb/ρb from wc and wm; the mean for λb/ρb was 0.131 ± 0.020 (N = 27). The relative mass of diaphyseal cortical bone to marrow was fairly constant; wc/(wc + wm) averaged 0.91 ± 0.03 (N = 27). In the light of the observations by De Bruyn et al. (6) that the capillary beds of cortex and marrow are mainly in series rather than in parallel, these values of FIAp do represent the tibial flow rather than either marrow or cortex separately.

Instantaneous Extractions

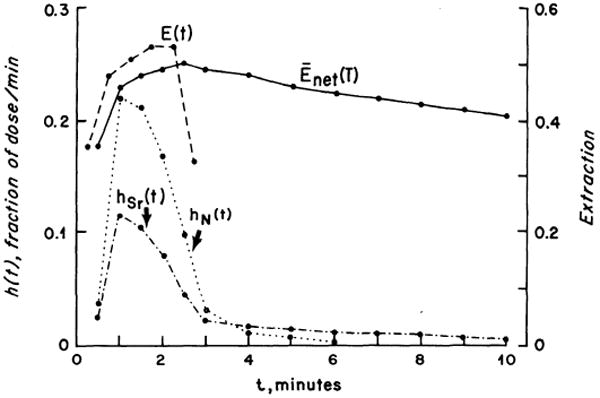

In Fig. 1 are shown femoral vein concentration-vs.-time curves, CN(t) and CSr(t), normalized to fraction of dose appearing per second in the outflow, hN(t) and hSr(t); hN(t) represents the reference curve of a nonpermeating tracer. The instantaneous fractional extraction, E(t), calculated by Eq. 5, represents averages over 30-s intervals and is plotted at the midpoint of each interval. The curve is typical in rising to a peak, Emax, after 1.5–2.0 min and then diminishing rapidly to zero as hSr(t) exceeds the reference, hN(t). Because the injection duration and the transtibial transit time were long and because return of extracted 85Sr from the extravascular region back into the blood was apparently slow (the tail of hSr(t) is low), the mean value of E(t) around Emax, from t = 1.5−2.5 min, was chosen to be most representative; this was 0.53 ± 0.08 (N = 12). The values decrease slightly with increasing flow.

FIG. 1.

Normalized femoral vein concentration-vs.-time curves for T-1824 [hN(t)] and Sr [hSr(t)] obtained after injection into the dog tibial nutrient artery. Instantaneous extraction, E(t), and net extraction, Enet(t), of 85Sr were calculated by Eq. 5 and 6.

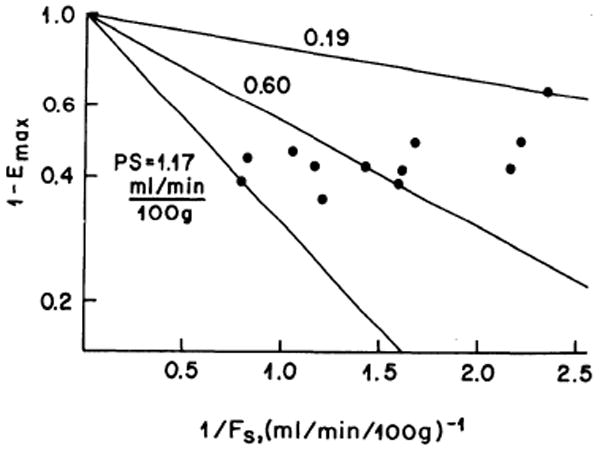

Permeability-Surface Area Products

Values for PS were calculated from the Emax values by using Eq. 1; these averaged 0.63 ± 0.29 ml/min per 100 g (N = 12) but were strongly influenced by the blood flow, ranging from 0.19 to 1.17 ml/min per 100 g with flows, Fs, ranging from 0.43 to 1.25 ml/min per 100 g. Because Fs is (1 – Hct)FIAp, the pertinent flow of Sr-containing fluid is the plasma flow. This is shown in Fig. 2. The theoretical lines of constant PS are straight lines on this plot; PS values of 0.19 and 1.17 ml/min per 100 g encompass the data. The PS values tend strongly to increase as Fs increases (toward the left of the figure), suggesting that more capillary bed is open at higher flows.

FIG. 2.

Relationship of 85Sr extraction, Emax, to flow, Fs. 1 – Emax is plotted on log scale versus the reciprocal of Sr-containing plasma or solvent flow. Encompassing and midrange theoretical lines of constant PS are shown. PS values tend strongly to increase as Fs increases.

Because there may be some question as to whether the flow, FIAp, remains unchanged during the experiment, values for PS/Fs can be calculated without using the estimates of Fs. Values of PS/Fs averaged 0.82 ± 0.15 (N = 12). These are within the range of values found for similar solutes in heart (8, 21) and skeletal muscle (12, 15, 16, 20).

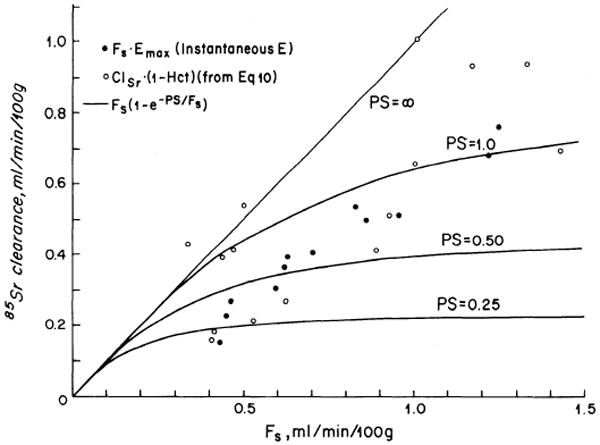

The effect of flow perhaps may be seen more clearly by plotting an instantaneous maximal clearance, the product of the instantaneous extraction, Emax, and the perfusate flow, Fs (Fig. 3). The maximal clearance is always less than Fs because Emax is always less than 1, which simply restates that, with incomplete extraction, clearance must underestimate flow. The data are seen to cross through the theoretical lines for constant values of PS. At low flows, the data are scattered around the curves for PS = 0.25 to 0.5 ml/min per 100 g; at high flows, the data show PS values of 0.5 to 1.0 ml/min per 100 g. If the data are regarded as a continuum, with much scatter in individual observations, then increases in Fs have resulted in increases in P or S (presumably the latter) by maintaining patency of more small vessels for more of the time.

FIG. 3.

Theoretical clearance-vs.-blood flow curves at constant PS (solid lines) with experimentally measured (IAp) solvent flow data and 85Sr clearance. The latter was determined both by measurement in the arteriovenous concentration difference group (open circles) and by calculation using Fs and Emax from the instantaneous extraction group (solid circles). In both sets of experimental data, Cl-F relationships tend to be more linear than are the theoretical curves, indicating an increase in PS with flow increase. Clearances are less than flow because extraction is incomplete.

Also in Fig. 3 are the measured plasma clearances, (1 – Hct) times whole blood clearance, of 85Sr from the arteriovenous concentration difference group. These data show the same apparent increase in PS with flow increase as do those calculated from Fs and Emax.

Net Extractions

Enet(t), calculated by Eq. 6, gives the retention of 85Sr as a fraction of the portion of the dose of the reference tracer that has emerged. Its peak is ordinarily reached one-half interval after the peak of Emax but is lower because it is an average. As backdiffusion of 85Sr from bone to blood continues, values of Enet(t) diminish gradually. Maximal values of Enet averaged 0.50 ± 0.07 (N = 12). Values of Enet (10 min), the final values obtained during each run, were 0.41 ± 0.06 (N = 12). If all tracer is accounted for and all of the reference tracer has emerged, Enet(10 min) should be identical to RSr(10 min), the fraction of the dose of 85Sr remaining in the bone at 10 min.

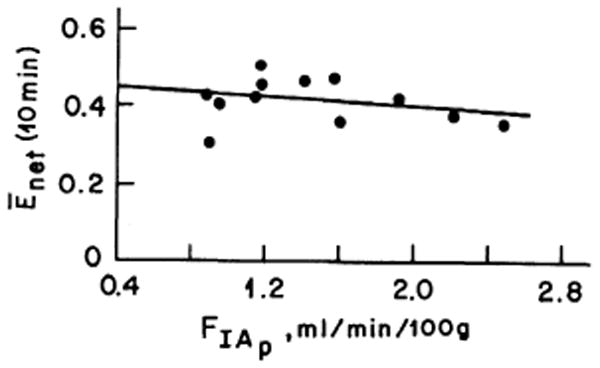

Enet(10 min) showed a small diminution at higher tibial blood flows (Fig. 4) similar to that reported by Bosch (4, his Fig. 6). This diminution is much less than would be expected for a system with a constant PS over a range of flows and therefore supports the evidence from the Emax values that more surface area becomes available for exchange at higher flows (see DISCUSSION).

FIG. 4.

Net 85Sr extraction [Enet(10 min)] versus estimated blood flow (FIAp). Flow has a minimal effect on extraction. The regression equation is Enet(10 min) = 0.44 − 0.22 FIAp (r = 0.20).

Residual 85Sr in Tibia

The fraction of the dose of 85Sr remaining in the tibia at the end of 10 min, RSr(10 min), was measured by direct counting of the whole tibia; the mean was 0.35 ± 0.06 (N = 12) as calculated by using Eq. 7. When this was divided by Enet(10 min) from Eq. 6, the fraction reaching the femoral vein by that time, the ratio for each experiment averaged 0.86 ± 0.19 (N = 12), showing that not all of the tracer was accounted for. It is most likely that the remaining fraction, 1 – 0.94 ± 0.08 from Eq. 8, was contained in the venous blood lying between the tibial nutrient vein and the femoral vein or bypassed the femoral vein (via the gluteal vessels, for example). This missing fraction was only 0.06 of the total dose.

Tibial Arteriovenous Extraction of 85Sr

Instantaneous arteriovenous differences could not be obtained because the nutrient vein outflow was too small to be separated into sequential samples. The mean extraction over the 10-min periods, from Eq. 9, was 0.53 ± 0.28 (N = 15). This mean was larger than the mean value for Enet(10 min), 0.41 ± 0.06 (N = 12), obtained in the other set of experiments in which the extraction was obtained by comparison with a nonextracted reference tracer. However, the extreme variation in tissue extraction is apparent and, although the mean extraction from a number of animals may approach the true tissue extraction, heterogeneity is a real problem. Values generated from this type of experiment are open to question.

Tibial 85Sr clearances, ClSr, calculated from the average arterial concentration and bone content of 85Sr at 10 min by using equation 10 had a mean value of 2.8 ± 0.86 ml/min per 100 g on the cannulated side compared to 2.95 ± 1.1 on the noncannulated side (N = 15). Clearance by the diaphyseal segment, into which blood could enter only by metaphyseal collaterals because the nutrient artery was cannulated but not perfused, was also calculated by Eq. 10, using C*Sr for this segment. The diaphyseal clearances averaged 1.00 ± 0.50 ml/min per 100 g, compared to 1.55 ± 0.73 on the noncannulated side. The diaphyseal plasma clearances are the blood clearances (calculated from Eq. 10) times (1 – Hct) and are plotted as the open circles in Fig. 3. The diaphyseal weight, wd (marrow + cortex), averaged 41 % of the total tibial weight, wt; the metaphyseal-epiphyseal weight, wM, is given by wt – wd. Metaphyseal-epiphyseal clearances, ClM, which could be calculated directly by using metaphyseal C*Sr in equation 10, can also be calculated by ClM = (wtClt – wcCld)/wm. Values of ClM averaged 4.11 ± 1.23 ml/min per 100 g (N = 15), which is much higher than the diaphyseal clearances (averaging 1.00 ml/min per 100 g). This difference may be due partly to higher metabolic activity in the metaphyseal-epiphyseal region than in the diaphysis and partly to a reduction of diaphyseal flow after nutrient artery cannulation. What is clear is that diaphyseal collateral flow is substantial and is only one-third less than the normal flow to the region.

An apparent diaphyseal flow, Cld/EAV, can be calculated by using Cld and Equation 10 with diaphyseal C*Sr and EAV from nutrient vein sampling. The ratio of these apparent flows to the paired values for FIAp gave mean values for (Cld/EAV)/FIAp of 1.86 ± 1.68 (N = 15). There are too many sources of systematic and random variation to allow a serious comparison of Cld/EAV to FIAp; the estimates are at different times, Cld represents flow that has entered the diaphysis via metaphyseal collaterals, and EAV is extraction from blood which departed via the nutrient vein whereas FIAp represents the washout of tracer introduced via the nutrient artery but with flow blocked and the blood flow entering via collaterals and leaving by both the diaphyseal nutrient vein and by metaphyseal veins. Despite these problems, the estimates are reassuringly close and probably imply that the physiologic state is reasonably constant in these experiments and that these diaphyseal flows are probably not much lower than the flow in the intact animal.

Discussion

The main contribution of this study is the measurement of instantaneous extractions and their interpretation in regard to estimation of capillary PS values in bone. The closest previous data are those of Copp and Shim (5, their Table 2) who found about 76 % extraction of 85Sr in comparison with albumin over 5 min in five dogs after nutrient artery injection, and of Bosch (4, Fig. 2) who found 40–65 % extraction of 45Ca over the first 0–40 min in comparison with albumin after nutrient artery injection (by arteriovenous difference with nutrient vein sampling). Copp and Shim's very high extraction may be explained by the abnormally low flow likely to occur in their surgical preparation. Bosch's highest values are similar to our own (Fig. 2).

The main barrier to escape from the blood is clearly the capillary membrane. One reason for the firmness of this conclusion is that the retention of the 85Sr that has entered the extravascular region is quite long, so that Enet(t) falls only slowly. This occurs when the extravascular volume of distribution is fairly large; presumably this is so because 85Sr is being taken into the large pool of Ca2+ on bone surfaces. Consider the system to consist of blood, capillary membrane, interstitial fluid, osteal membrane, and Ca2+ pool in ossified bone. Retention in a large pool implies that entry to it across the osteal membrane was rapid relative to return of tracer across the capillary barrier to the blood. This forces us to regard the capillary membrane as the high-resistance barrier. Combining that with the fact that the earliest values of E(t) calculated from hN(t) and hSr(t) should theoretically be governed solely by the capillary barrier (2) strengthens our interpretation that Emax gives values for the PS of the capillary membrane alone.

One can conceive of further experiments to confirm this view; they would be tests to determine if the apparent values for PS are in accordance with an active, saturable transport mechanism, as most likely occurs at the osteal membrane as suggested by Geisler and Neuman (7) and by Talmage (17), or with a purely passive mechanism, as one would anticipate for capillary membrane, although exceptions exist. If the transport is passive, then hydrophilic molecules of different charges and different sizes would have PS values that are related to each other by simple equations based on their sizes and diffusion coefficients in water. If the transport is active, 85Sr uptake should be dependent on Sr and Ca concentrations in the blood, and transport might be blocked by competitors such as Mg2+, Mn2+, or La3+.

Precision of the values for capillary PS is decreased by heterogeneity of regional flows, which obviously exists because metaphyseal and diaphyseal clearances differ. Little inaccuracy is introduced when there is no backdiffusion of tracer from the extravascular region to the blood, and in this study we are therefore taking advantage of the long retention and resultant smallness of the backdiffusion. It is clear that the variation in estimates is quite large, which very likely means that both biologic variations in PS and experimental error in its estimation are substantial. The influence of the regional heterogeneity is decreased by using Emax to get a representative average (2, 3) rather than by using an extrapolation back to the earliest sample, the E(O) technique advocated by Yudilevich et al. (12, 20) and in which heterogeneity has a more prominent influence, because it tends to represent principally the regions of shortest transit time, highest flow, and lowest extraction.

The deposition of 85Sr in bone is a direct measure of net extraction. These values must always be less than the maximal instantaneous extraction which is due mainly to the unidirectional efflux from blood across the capillary membrane. Net extraction represents the difference between efflux from blood and return flux to blood and, after several minutes, will be dominated by the uptake into the osseous Ca2+ pool. Values for net extractions in this study and in others (Table 1) range widely but mainly are about 50%. This emphasizes that the Ca2+ pool is very large and fairly accessible. In accordance with the idea that an active uptake mechanism into bone may be working at higher rates in growing animals than in adults, more 85Sr was deposited in immature than in adult animals (18, 19, and Table 1). There is no reason to believe that the bone uptake of Ca2+ should be at all affected by the flow except with most marked decreases in flow and delivery of substrates and oxygen.

TABLE 1. Net extraction of calcium and strontium by bone.

| Author | Species | N | Bone | Maturity | Isotope | Injection Site | Method | Extraction, Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ray et al. (14) | Dog | 6 | Femur | Adult | 45Ca | Systemic | EAV | 0.52±0.02 | 0–5 min |

| 0.45±0.02 | 0–10 min | ||||||||

| Weinman et al. (18, 19) | Dog | 4 | Femur | Immature | 85Sr | Local | Residue | 0.42 | |

| Dog | 1 | Femur | Immature | 47Ca | Local | Residue | 0.55 | ||

| Dog | 4 | Skeleton | Immature | 85Sr | Systemic | Residue | 0.43 | ||

| Dog | 3 | Skeleton | Immature | 47Ca | Systemic | Residue | 0.43 | ||

| Dog | 2 | Skeleton | Adult | 85Sr | Systemic | Residue | 0.27 | ||

| Copp & Shim (5) | Dog | 10 | Tibia | Adult | 85Sr | Local | E(t) | 0.76 | |

| Laurnen & Kelly (11) | Dog | 7 | Tibia | Adult | 85Sr | Local | Residue | 0.31±0.021 | |

| Bosch (4) | Dog | 4 | Tibia | Immature | 45Ca | Local | EAV | 0.40±0.65 | 0–40 min |

| 0.35±0.45 | 40–360 min | ||||||||

| This study | Dog | 12 | Tibia | Adult | 85Sr | Local | Enet (10 min) | 0.41±0.06 | |

| RSr (10 min) | 0.35±0.06 | ||||||||

| Dog | 15 | Tibia | Adult | 85Sr | Systemic | EAV | 0.53±0.28 | ||

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Mr. Glenn Christensen for his assistance with the experiments.

This investigation was supported in part by Research Grant AM-15980 from the National Institutes of Health.

Glossary

- FIAp, Fs

flow (ml/min per 100 g), whole blood or solvent (plasma), measured by IAp method

- λc, λm, λb

tissue-blood partition coefficients for IAp in cortex, marrow, or whole bone

- ρc, ρm, ρb

density (g/ml) of cortex, marrow, or whole bone

- wc, wm

weight (g) of cortex or marrow

- Vc, Vm

volume (ml) of cortex or marrow

- t

time (seconds)

- T

time (seconds) at end of IAp measurement

- t′

dummy variable for time between 0 and t in Eq. 3

- C*(t)

tibial isotope emission count rate (counts/min)

- R(t)

residue function, fraction of injectate remaining in blood at time, t

- RSr(10 min)

residue of 85Sr dose remaining in tibia at 10 min

- IAp

125I-labeled 4-iodoantipyrine

- subscripts Sr, N

85Sr; nondiffusible, albumin-bound T-1824

- hSr(t), hN(t)

normalized concentration-vs.-time curves of Sr and T-1824 in Eq. 3 and 4

- CSr, CN

radioactivity of 85Sr (counts/min per ml) and concentration of T-1824 (mg/liter) in Eq. 3

- E(t)

instantaneous 85Sr extraction in Eq. 5

- Enet(t), EAV

average net 85Sr extraction in Eq. 6; mean tibial 85Sr extraction from arteriovenous concentration difference in Eq. 9

- C̄A, C̄NV

average Sr concentration in carotid artery and tibial nutrient vein (counts/min per ml blood)

- Cl

clearance (ml/min per 100 g)

References

- 1.Allen TH, Krzywicki HJ, Roberts RE. Density, fat, water and solids in freshly isolated tissues. J Appl Physiol. 1959;15:1005–1008. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1959.14.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassingthwaighte JB. A concurrent flow model for extraction during transcapillary passage. Circulation Res. 1974;35:483–503. doi: 10.1161/01.res.35.3.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassingthwaighte JB, Yipintsoi T. Organ blood flow, wash-in, washout, and clearance of nutrients and metabolites. Mayo Clin Proc. 1974;49:248–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosch WJ. Plasma 45Ca clearance by the tibia in the immature dog. Am J Physiol. 1969;216:1150–1157. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1969.216.5.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Copp DH, Shim SS. Extraction ratio and bone clearance of Sr85 as a measure of effective bone blood flow. Circulation Res. 1965;16:461–467. doi: 10.1161/01.res.16.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Bruyn PPH, Breen PC, Thomas TB. The microcirculation of the bone marrow. Anat Record. 1970;168:55–68. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091680105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geisler JZ, Neuman WF. The membrane control of bone potassium. Proc Soc Exptl Biol Med. 1969;130:608–612. doi: 10.3181/00379727-130-33618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guller B, Yipintsoi T, Orvis AL, Bassingthwaighte JB. Myocardial sodium extraction at varied coronary flows: estimation of capillary permeability by residue and outflow detection. Circulation Res. doi: 10.1161/01.res.37.3.359. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly PJ. Comparison of marrow and cortical bone blood flow by 125I-labeled 4-iodoantipyrine (I-Ap) washout. J Lab Clin Med. 1973;81:497–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly PJ, Yipintsoi T, Bassingthwaighte JB. Blood flow in canine tibial diaphysis estimated by iodoantipyrine-125I washout. J Appl Physiol. 1971;31:38–47. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1971.31.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laurnen EL, Kelly PJ. Blood flow, oxygen consumption, carbon-dioxide production, and blood-calcium and pH changes in tibial fractures in dogs. J Bone Joint Surg. 1969;51A:298–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martín P, Yudilevich D. A theory for the quantification of transcapillary exchange by tracer-dilution curves. Am J Physiol. 1964;207:162–168. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1964.207.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rawson RA. The binding of T-1824 and structurally related diazo dyes by the plasma proteins. Am J Physiol. 1943;138:708–717. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray RD, Kawabata M, Galante J. Experimental study of peripheral circulation and bone growth: an experimental method for the quantitative determination of bone blood flow. III. Clin Orthop. 1967;54:175–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renkin EM. Transport of potassium-42 from blood to tissue in isolated mammalian skeletal muscles. Am J Physiol. 1959;197:1205–1210. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1959.197.6.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheehan RM, Renkin EM. Capillary, interstitial, and cell membrane barriers to blood-tissue transport of potassium and rubidium in mammalian skeletal muscle. Circulation Res. 1972;30:588–607. doi: 10.1161/01.res.30.5.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talmage RV. Calcium homeostasis-calcium transport-parathyroid action: the effects of parathyroid hormone on the movement of calcium between bone and fluid. Clin Orthop. 1969;67:210–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinman DT. Thesis. Mayo Graduate School of Medicine (University of Minnesota); Rochester: 1964. Skeletal clearance of Sr85 and Ca47 and bone blood flow in both normal and arteriovenous fistula animals. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinman DT, Kelly PJ, Owen CA, Jr, Orvis AL. Skeletal clearance of Ca47 and Sr85 and skeletal blood flow in dogs. Proc Staff Meetings Mayo Clinic. 1963;38:559–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yudilevich DL, Renkin EM, Alvarez OA, Bravo I. Fractional extraction and transcapillary exchange during continuous and instantaneous tracer administration. Circulation Res. 1968;23:325–336. doi: 10.1161/01.res.23.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziegler WH, Goresky CA. Kinetics of rubidium uptake in the working dog heart. Circulation Res. 1971;29:208–220. doi: 10.1161/01.res.29.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zierler KL. Equations for measuring blood flow by external monitoring of radioisotopes. Circulation Res. 1965;16:309–321. doi: 10.1161/01.res.16.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]