Abstract

Importance

Tobacco and alcohol use in movies could be influenced by product placement agreements. Tobacco brand placement was limited by the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) after 1998, while alcohol is subject to self-regulation only.

Objective

To examine recent trends for tobacco and alcohol use in movies. We expected that the MSA would be associated with declines in tobacco but not alcohol brand placement (hypothesis formulated after data collection).

Design

Content analysis.

Setting

Top 100 box-office hits released in the United States from 1996 through 2009 (N = 1400).

Intervention

The MSA, an agreement signed in 1998 between the state attorneys general and tobacco companies, ended payments for tobacco brand placements in movies.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Trend for tobacco and alcohol brand counts and seconds of screen time for the pre-MSA period from 1996 through 1999 compared with the post-MSA period from 2000 through 2009.

Results

Altogether, the 1400 movies contained 500 tobacco and 2433 alcohol brand appearances. After implementation of the MSA, tobacco brand appearances dropped exponentially by 7.0% (95% CI, 5.4%–8.7%) each year, then held at a level of 22 per year after 2006. The MSA also heralded a drop in tobacco screen time for youth- and adult-rated movies (42.3% [95% CI, 24.1%–60.2%] and 85.4% [56.1%–100.0%], respectively). In contrast, there was little change in alcohol brand appearances or alcohol screen time overall. In addition, alcohol brand appearances in youth-rated movies trended upward during the period from 80 to 145 per year, an increase of 5.2 (95% CI, 2.4–7.9) appearances per year.

Conclusions and Relevance

Tobacco brands in movies declined after implementation of externally enforced constraints on the practice, coinciding also with a decline in tobacco screen time and suggesting that enforced limits on tobacco brand placement also limited onscreen depictions of smoking. Alcohol brand placement, subject only to industry self-regulation, was found increasingly in movies rated for youth as young as 13 years, despite the industry’s intent to avoid marketing to underage persons.

Evidence is accumulating that movies influence substance use behaviors during adolescence. A 2012 Surgeon General’s report contains the following causal statement about movies and tobacco use among youth: “The evidence is sufficient to conclude that there is a causal relationship between depictions of smoking in the movies and the initiation of smoking among young people.”1(p602) Movies deliver billions of impressions of tobacco and alcohol imagery to US adolescents,2,3 as well as to youth in other countries.4 Children’s exposure to movie imagery of these substances has been associated with not only smoking5 but also early onset of drinking,6,7 heavier drinking,8 and abuse of alcohol.9

Paying for brand placement in entertainment media is common in the United States and considered a legitimate marketing practice by manufacturers of a variety of products. To avoid regulation, companies typically promulgate a self-regulatory structure; this happened for tobacco in 1989, when major US tobacco companies voluntarily incorporated limits on movie brand placements1 after the practice was criticized at a Senate subcommittee hearing on the topic.10 Yet, in the years following self-regulation, highly advertised cigarette brands continued to appear in one-third of films through 1996.11

In 1998, the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) between the state attorneys general and the major tobacco companies was executed. In the MSA, the tobacco industry signatories agreed to end product placements of their brands in film or television (Section III[e], Prohibition on Payments Related to Tobacco Products and Media),12 resulting in an external constraint on product placement deals, enforceable by the state attorneys general. The MSA does not require tobacco companies to confirm that no payments took place, but attorneys general charged with enforcing the settlement have sometimes asked them to do that when corresponding with them about movies in which their brands have appeared. The purpose of such correspondence was to prompt tobacco companies to inform movie studios that they do not have permission to use their brands in films.5(p408) Thus, the MSA offers a before-and-after opportunity to assess the impact of enforceable, externally imposed limits on product placement. An earlier study13 suggested a downward trend in tobacco brand appearances soon after signing the MSA, but it is not clear whether this trend has continued.

During the same period, alcohol brand placements in movies have been subject to self-regulation only and never been explicitly addressed until 1999 at the request of the Federal Trade Commission (http://www.ftc.gov/reports/alcohol/alcoholreport.shtm), which periodically examines the effectiveness of these voluntary guidelines for advertising and marketing to underage audiences. The 1999 Federal Trade Commission report requested that the industry “reduce the likelihood that alcohol product placement will occur in media with substantial underage appeal by restricting movie placements to films rated R or NC-17 (or unrated films with similarly mature themes).” A later report in 2008 indicated that the companies had found this recommendation unworkable because it was hard to know what a movie would be rated before it was produced (http://www.ftc.gov/os/2008/06/080626alcoholreport.pdf). The Beer Institute’s Advertising and Marketing Code and the Distilled Spirits Council for the US Code of Responsible Practices for Beverage Alcohol Advertising and Marketing now guide companies seeking product placement to avoid movies that primarily appeal to underage persons and portray drinking and driving, underage drinking, and alcoholism or alcohol abuse. They request that companies avoid advertising in any media in which the underage audience comprises more than 30%, but they offer no guidance on how to accomplish that with motion pictures. Thus, while the industry communicates intent to limit exposure to alcohol brands in movies aimed at the underage segment, no clear directive would limit product placements in movies aimed at the youth market. One study of alcohol brand appearances in 534 movies found that more than half contained an alcohol brand appearance, including 19.2% of G- or PG-rated movies.2

This study contrasts trends for tobacco and alcohol brand appearances and minutes of tobacco and alcohol screen time in the top 100 box-office hits for a 15-year period that spans the MSA. We plot trends for movies overall and for youth compared with adult (R-rated) movies.

METHODS

From 1996 through 2009, the 100 movies with the highest US box-office gross revenues were content coded for tobacco and alcohol. Using previously validated methods, 2 trained coders viewed theater versions of movies on videotape or DVD. The coders had the ability to freeze any frame multiple times for clarification. Coders recorded (1) the duration of tobacco use, (2) the presence of tobacco brands, (3) the duration of alcohol use, and (4) the presence of alcohol brands.

Duration of tobacco use was defined as the number of seconds that any tobacco was used or handled onscreen. For example, if a character smoked a cigarette during a scene that lasted several minutes, but the cigarette appeared onscreen only twice for 3 seconds each time, the tobacco exposure time for this occurrence was recorded as 6 seconds. Timing occurred without regard to the number of characters smoking. For example, if a scene contained 30 seconds of character use and 20 seconds of background use and the 2 occurrences overlapped by 10 seconds, the total tobacco exposure time for the 2 occurrences combined was recorded as 40 seconds.

Duration of alcohol use was defined as the number of seconds of real or implied use of an alcoholic beverage by 1 or more characters, including purchases and occasions when an alcoholic beverage was clearly in the possession of a character. Empty alcoholic beverage containers and those that were displayed but not implied as being consumed by a character (eg, in bars) were not timed as alcohol use. Alcohol use is reported in minutes and includes use from the moment the alcohol appeared onscreen to the end of each occurrence.

A tobacco brand appearance was defined as any appearance of a tobacco brand or recognizable logo or trademark (eg, a tobacco brand was featured on a billboard or on a convenience store display in the background) or any verbal mention. All appearances of tobacco brands (including rolling papers or spit tobacco) were coded, whether in use by a character or not. Alcohol brands were counted the same way.

Ten percent of the movies were examined by both coders to monitor reliability. Average κ reliabilities for 5-second blocks within each movie were 0.76 for alcohol time and 0.97 for tobacco time. For alcohol and tobacco brand counts, Pearson correlation coefficients comparing counts by movie were 0.99 and 0.98, respectively.

In 2005, Adachi-Mejia et al13 examined a trend for the proportion of the top 100 box-office movies containing any brand placement from 1996 through 2003 and showed a drop in that proportion following the MSA. That approach to the analysis obscured a dramatic drop in the count of brand placement scenes because it failed to consider the near elimination of movies with multiple cigarette brand appearances. For the present analysis, brand appearances were summed across movies for each year. Total brand counts relate more closely to measures of movie exposure that have been linked with behavior, which acknowledges research14 suggesting that smoking is more related to the number of impressions of smoking that adolescents see rather than the prevalence of 1 or more impressions seen in the movies.

Movies take 1 to 2 years to produce, so we expected a 1- to 2-year lag for the MSA, brokered in 1998, to affect tobacco brand appearances. One aim of the MSA was to eliminate all paid tobacco brand placement from movies, so the trend in tobacco brands was studied irrespective of the movie rating. Raw data suggested the decline in annual tobacco brand counts after 1999 was best fit with a nonlinear least squares model using a 3-parameter exponential decay regression function:

a1 + a2 × e(−a3×t)

where a1 estimates the asymptote (minimum) and a3 estimates the rate of annual drop; t represents time (in years). Linear least squares models were used to assess trends for the annual number of alcohol brand appearances, with adult-rated movies (R) modeled separately from youth-rated movies (G, PG, and PG-13) to determine whether self-regulation had the intended effect of limiting alcohol brand appearances in movies aimed at youth.

Average movie screen time was modeled with movie (by year of release) as the unit of analysis. To reduce the influence of high outliers (movie screen time was skewed left) and accommodate movie data with no tobacco use, we made the following transformation: y = log(1 + screen time [in minutes]). We entered year of release to model the historical downward trend documented by Jamieson and Romer15 and added a dummy variable to assess the effect of the MSA after 1999 (0 for movies prior to 2000 and 1 otherwise). Trend data for movie tobacco and alcohol screen time were modeled separately for youth- and adult-rated movies because neither was specifically limited by the MSA. All analyses were done using statistical package S+ (TIBCO Spotfire).

RESULTS

TOBACCO AND ALCOHOL BRANDS OVERALL

Of the 1400 movies in the period, 906 (64.7%) were rated for youth and 494 (35.3%) were rated for adults only. The movies contained 500 tobacco brand appearances and 2433 alcohol brand appearances, with 231 (46.2%) and 1528 (62.8%), respectively, found in movies rated for adolescent viewing. The 5 most common tobacco brands were Marlboro (33.4%), Camel (10.0%), Kool (5.8%), Winston (4.8%), and Newport (4.4%). The 5 most common alcohol brands were all from beer companies: Budweiser (17.7%), Miller (10.7%), Heineken (5.0%), Coors (2.8%), and Corona (2.3%).

TRENDS IN TOBACCO BRAND APPEARANCES AND ONSCREEN USE

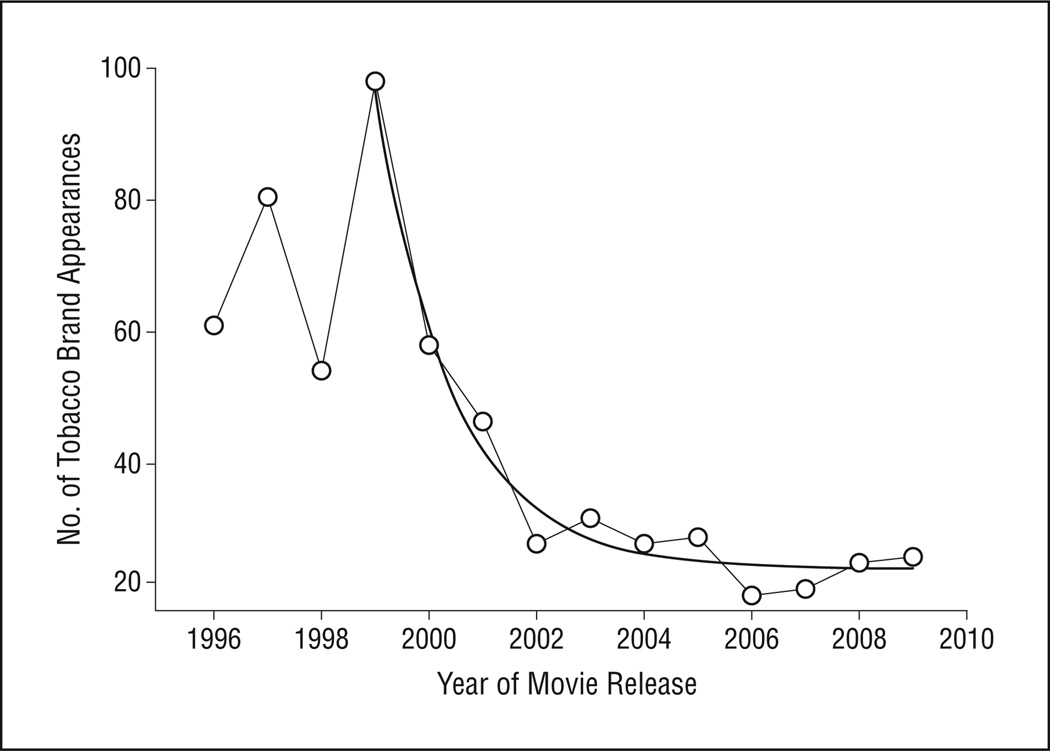

The trend in tobacco brand appearances is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows the actual data superimposed on the predicted plot from the regression. Prior to 2000, tobacco brand appearances in the top 100 box-office hits ranged from 54 to 98 per year. Beginning in 2000, there was an exponential decline in brand appearances of 7.0% (95% CI, 5.4%–8.7%) per year, with little further decline below 22 per year after 2006. A subgroup analysis (results not shown) found similar declines after 1999 for both youth- and adult-rated movies.

Figure 1.

Trend in tobacco brand appearances in the top 100 movies with the highest US box-office gross revenues from 1996 through 2009. Points show the actual data, and the bold line shows the post-1999 trend estimate. Rate of decline is 7.0% per year.

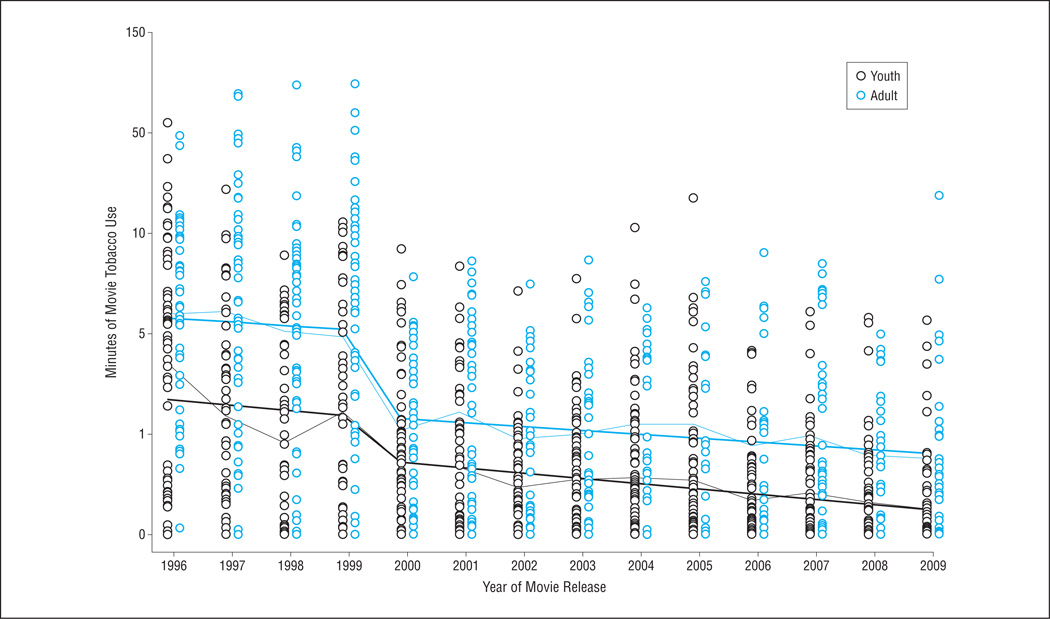

Trends in minutes of onscreen tobacco use per movie are shown in Figure 2, grouped by whether the movies were youth or adult rated. Figure 2 plots the actual data, with minutes of screen time for individual movies plotted as points for each year, along with the lines from the regression analyses. When minutes of onscreen tobacco use were fitted on the log scale, there was a linear downward trend for youth- and adult-rated movies during the entire period. Large and statistically significant decreases in onscreen smoking also occurred between 1999 and 2000, with declines of 42.3% (95% CI, 24.1%–60.2%) and 85.4% (56.1%–100.0%) in youth- and adult-rated movies, respectively.

Figure 2.

Trends in tobacco screen time (in minutes) for the top 100 movies with the highest US box-office gross revenues from 1996 through 2009 by whether they were youth or adult rated.

TRENDS IN ALCOHOL BRAND APPEARANCES AND ONSCREEN USE

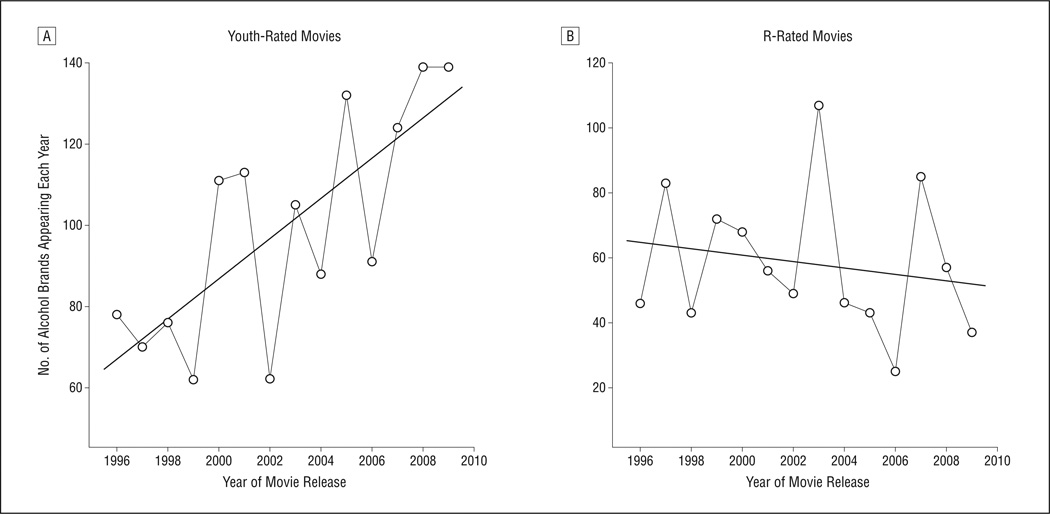

There was no statistically significant trend for alcohol brand appearances overall or coinciding with the MSA during the period. However, when trends were plotted according to rating category, there was a statistically significant upward trend in youth-rated movies (Figure 3), with alcohol brand appearances increasing by 5.2 (2.4–7.9) per year, from a total of about 80 per year in the top 100 box-office hits at the beginning of the period to 145 per year at the end. There was a small statistically significant overall decline in minutes of screen alcohol use in adult-rated movies (−1.9 [95% CI, −1.5 to −3.6] minutes per year) but no change in movies rated for youth.

Figure 3.

Trends of movie alcohol brand counts from (A) youth-rated and (B) R-rated movies, with a linear trend line. For youth-rated movies, slope = 4.97 (P = .002); for R-rated movies, slope = −0.99 (P = .52).

DISCUSSION

This study confirms a rapid and sustained downward trend for tobacco brand appearances that began with the enforcement of the MSA. Onscreen tobacco use showed a continuous decline during the period but also a large decrease coinciding with the MSA, suggesting that eliminating the opportunity for placement of cigarette brands also substantially decreased nonbranded tobacco imagery. Although no data are publicly available on the amount of paid tobacco placement in movies at any time (the tobacco industry denies any paid placement after its self-imposed ban in 1991), the data suggest that the tobacco industry was responsible for many of the tobacco brand appearances until the enforcement of the MSA led to rapid and sustained reductions of the practice.

Alcohol brand appearances were far more common than tobacco appearances throughout the period and showed no declining trend. To the contrary, the sizable and statistically significant upward trend for alcohol brand appearances in youth-rated movies suggests that current self-regulatory guidelines are not adequately protecting youth. To the extent the alcohol branding in these movies is paid for, it can be expected to increase alcohol screen time and lead to higher exposure to onscreen alcohol use as well. This practice raises health concerns in light of longitudinal studies linking movie alcohol exposure with problematic underage drinking.6–9

One response to the failure of self-regulation to limit brand appearances of alcohol would be to regulate alcohol advertising, an action not likely given the current regulatory climate. Another possibility would be a voluntary agreement, such as the MSA, which the tobacco industry negotiated to avoid further lawsuits from state attorneys general. However, we are not aware of a plan to sue alcohol companies for costs incurred by states due to alcohol consumption, although those costs are enormous.16 That leaves us to recommend better self-regulatory guidelines for alcohol placement in entertainment media, something the Federal Trade Commission could propose and that could decrease youth exposure if the industry enforced them.

SUGGESTED SELF-REGULATION STANDARDS FOR THE ALCOHOL INDUSTRY

The following amendments to the Beer Institute Advertising and Marketing Code and the Distilled Spirits Council for the US Code of Responsible Practices for Beverage Alcohol Advertising and Marketing guides are recommended. First, no payments should be made for alcohol placements in youth-rated movies or television shows. Adolescent viewership of G-, PG-, and PG-13–rated movies is much higher than for R-rated movies3 and is likely to violate industry standards for measured media for many of these movies. The industry’s suggestion that ratings cannot be known beforehand rings hollow. Movie rating is a key determinant of box-office revenue, so much so that producers routinely negotiate the rating before releasing the funding for production. That fact is the reason many movies receive multiple trips to the ratings board, as objectionable scenes are cut to achieve the agreed-upon rating. If the rating has not been negotiated beforehand, the industry should avoid brokering agreements for product placement to avoid the possibility of placement in a film that will be marketed to youth.

Second, the amount paid for product placement and names of all movies and television shows in which brands are placed should be reported. Transparency is an important part of successful self-regulatory strategies. The Federal Trade Commission requires alcohol companies to report marketing expenditures by category every 2 to 3 years. The current schema does not break out media (movie, television, and music) product placement as a separate category or require a listing of titles in which placements were successfully obtained. If alcohol companies were required to report such a list, any company placing its brand in a movie, television show, or song aimed at youth would have to account for this behavior.

SUGGESTED SELF-REGULATION STANDARDS FOR THE MOVIE INDUSTRY

The Motion Picture Association of America has refused to include legal substances in its ratings system in any meaningful way, despite evidence for movies with smoking as a cause of youth smoking and increasingly compelling evidence for the same regarding alcohol. Guidelines for rating movies with smoking have already been suggested (http://www.smokefreemovies.ucsf.edu/solution/index.html) and endorsed by many organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics. Regarding alcohol, movies that depict drinking in contexts that could increase curiosity or acceptability of unsafe drinking should be rated R. The ratings system was created “to give parents clear, concise information about a film’s content, in order to help them determine whether a movie is suitable for their children.”17(p6) Now that we have good evidence to support health consequences—for smoking and drinking—the movie industry should amend the ratings system in response to this new information. For example, no movie with a youth rating should show underage drinking, binge drinking, alcohol abuse, or drinking and driving. Rating such movies R preserves the opportunity for free speech (the director may retain the material as long as he or she is willing to accept an adult rating) and offers a degree of protection to the adolescent audience (because fewer youth are exposed to R-rated movies).

LIMITATIONS

Our data speak only to the year 2009; recent publications using a somewhat different method and sample and including 2011 suggest an upward trend for smoking in movies from 2010 to 2011.18 The upward trend in alcohol brand appearances in youth-rated movies should not be misinterpreted to imply that the industry has increasingly targeted youth in its brand placement practices, only that it has not adequately determined whether the movies will be marketed to youth when considering the buying of such placements. The increasing trend in alcohol brand appearances in PG-13–rated movies over time could be explained, in part, by another trend that has taken place during the study period—a higher proportion of movies among the top 100 have fallen into the youth-rated category. About half of the top 100 box-office hits were R rated prior to 2000, but closer to 30% have been R rated in more recent years. Whatever the reason for the trend in alcohol brand appearances in movies for youth audiences, we find it concerning because these movies garner higher youth viewership, and therefore the brand appearances reach a larger share of the adolescent population.3

In summary, this study found dramatic declines in brand appearances for tobacco after such placements were prohibited by an externally monitored and enforced regulatory structure, even though such activity had already been prohibited in the self-regulatory structure a decade before. During the same period, alcohol brand placements, subject only to self-regulation, increased significantly in movies rated acceptable for youth audiences, a trend that could have implications for teen drinking.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grants CA 077026 and AA015591 from the National Institutes of Health (Dr Sargent).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Ms Bergamini and Dr Sargent had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Sargent. Acquisition of data: Bergamini and Sargent. Analysis and interpretation of data: Demidenko and Sargent. Drafting of the manuscript: Bergamini and Sargent. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Demidenko and Sargent. Statistical analysis: Demidenko. Obtained funding: Sargent. Administrative, technical, and material support: Bergamini and Sargent. Study supervision: Bergamini and Sargent.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Dalton MA, Sargent JD. Youth exposure to alcohol use and brand appearances in popular contemporary movies. Addiction. 2008;103(12):1925–1932. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sargent JD, Tanski SE, Gibson J. Exposure to movie smoking among US adolescents aged 10 to 14 years: a population estimate. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):e1167–e1176. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking in popular contemporary movies and youth smoking in Germany. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(6):466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Institute. The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. Bethesda, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2008. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19. NIH Publication 07-6242. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD. Longitudinal study of exposure to entertainment media and alcohol use among German adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):989–995. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sargent JD, Wills TA, Stoolmiller M, Gibson JJ, Gibbons FX. Alcohol use in motion pictures and its relation with early-onset teen drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(1):54–65. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Gerrard M, et al. Watching and drinking: expectancies, prototypes, and friends’ alcohol use mediate the effect of exposure to alcohol use in movies on adolescent drinking. Health Psychol. 2009;28(4):473–483. doi: 10.1037/a0014777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wills TA, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Stoolmiller M. Movie exposure to alcohol cues and adolescent alcohol problems: a longitudinal analysis in a national sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(1):23–35. doi: 10.1037/a0014137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snyder SL. Movies and product placement: is Hollywood turning films into commercial speech? Univ Ill Law Rev. 1992;1:301–337. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sargent JD, Tickle JJ, Beach ML, Dalton MA, Ahrens MB, Heatherton TF. Brand appearances in contemporary cinema films and contribution to global marketing of cigarettes. Lancet. 2001;357(9249):29–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03568-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Master Settlement Agreement between 46 state attorneys general and participating tobacco manufacturers. [Accessed December 14, 2011];1998 Nov 23; http://www.naag.org/backpages/naag/tobacco/msa/msa-pdf/1109185724_1032468605_cigmsa.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adachi-Mejia AM, Dalton MA, Gibson JJ, et al. Tobacco brand appearances in movies before and after the Master Settlement Agreement. JAMA. 2005;293(19):2341–2342. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.19.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sargent JD, Worth KA, Beach M, Gerrard M, Heatherton TF. Population-based assessment of exposure to risk behaviors in motion pictures. Commun Methods Meas. 2008;2:1–18. doi: 10.1080/19312450802063404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamieson PE, Romer D. Trends in US movie tobacco portrayal since 1950: a historical analysis. Tob Control. 2010;19(3):179–184. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.034736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouchery EE, Harwood HJ, Sacks JJ, Simon CJ, Brewer RD. Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the U.S., 2006. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(5):516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motion Picture Association of America. The movie rating system: its history, how it works, and its enduring value. [Accessed November 29, 2012];2010 http://www.filmratings.com/filmRatings_Cara/downloads/pdf/about/cara_about_voluntary_movie_rating.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glantz SA, Iaccopucci A, Titus K, Polansky JR. Smoking in top-grossing US movies, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:120170. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]