Abstract

Background

Observational studies have generally been viewed as incurring minimal risk to participants, resulting in fewer ethical obligations for investigators than intervention studies. In 2004, the lead author (AN) carried out an observational study measuring sexual behavior and the prevalence of HIV, syphilis, and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), among Tanzanian agricultural plantation residents (results reported elsewhere). This article uses an ethical lens to consider the consequences of the observational study and explore what, if any, effects it had on participants and their community.

Methods

Using a case study approach, we critically examine three core principles of research ethics—respect for persons/autonomy; beneficence/nonmaleficence; and distributive justice—as manifested in the 2004 observational study. We base our findings on three sources: discussions with plantation residents following presentations of observational research findings; in-depth interviews with key informants; and researcher observations.

Results

The observational research team was found to have ensured confidentiality and noncoercive recruitment. Ironically, maintenance of confidentiality and voluntary participation led some participants to doubt study results. Receiving HIV test results was important for participants and contributed to changing community norms about HIV testing.

Conclusions

Observational studies may act like de facto intervention studies and thus incur obligations similar to those of intervention studies. We found that ensuring respect for persons may have compromised the principles of beneficence and distributive justice. While in theory these three ethical principles have equal moral force, in practice, researchers may have to prioritize one over the others. Careful community engagement is necessary to promote well-considered ethical decisions.

Keywords: Africa, autonomy, beneficence, cross-sectional, distributive justice, ethics, observational research

While much consideration has been given to the ethical obligations of researchers conducting intervention studies (CIOMS preamble 2002; Emanuel, Wendler, and Grady 2000; Frey 2003), scant attention has been paid to the conduct of observational studies, particularly those that involve biological testing for stigmatized diseases. Institutional review boards (IRBs) often consider observational studies to pose minimal risks to participants because they do not involve interventions that affect participants or their communities. We contend that the application of core ethical principles to the evaluation of observational research merits further consideration. By way of example, we apply these principles to evaluate the ethics of an observational prevalence study of HIV, other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and associated risk factors, in Tanzania. The original observational study was not designed to generate data for rigorous ethical analysis, but was designed to be ethically compliant. This qualitative evaluation applies ethical theory to assess the consequences of the observational study.

BACKGROUND

Agricultural Plantation Workers

Across Sub-Saharan Africa, the millions of men and women who work on agricultural plantations represent a unique, understudied, and potentially vulnerable population. One such plantation, called the Tanzania Sugar Enterprises (TSE),1 is located in northern Tanzania near Mount Kilimanjaro, and employs about 3,800 people. TSE is, in many respects, a “company town.” The majority of these workers have their families residing with them in small cement houses that are clustered in 10 camps throughout the 55-square-mile plantation; TSE has a small hospital on the plantation. In 2004, the lead author (AN) carried out observational research on the sexual health of people living on this large sugar plantation (Norris 2006). This and earlier studies are discussed in the following sections.

Pilot Study, 2002

In 2002, AN first went to TSE to carry out a pilot study to ascertain plantation residents’ views about HIV and HIV testing. The research established that people were very concerned about HIV in their community. Many were fearful that “HIV is everywhere at TSE” and that, consequently, there was no way to avoid infection. Interviews and focus-group discussions about HIV testing suggested heterogeneity of views: Some people strongly desired the opportunity to be tested, while others expressed anxiety and uncertainty. In particular, those who feared testing were afraid that an HIV-positive result would simply be an “announcement of the funeral,” and that the stress of knowing would hasten death, maybe by causing the person to become suicidal. Intimate partner violence is another potential risk for participants in any STI study, should an infected partner choose to disclose his or her status to the other partner.

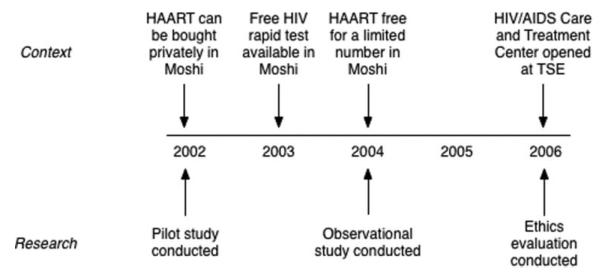

Despite these fears, however, the majority of people (70%) surveyed in a random sample (n = 165) in 2002 indicated that they would be tested for HIV if such a test were made available (Norris unpublished data 2002). Some plantation residents expressed concerns that while it was possible to obtain an HIV test at the TSE hospital, it was costly and the hospital had a poor reputation related to the protection of patients’ confidentiality. In 2002, HIV testing was also available for a fee in the nearby town of Moshi. It is noted that availability of HIV testing and treatment with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was changing throughout the research period (see Figure 1). By characterizing the interest of plantation residents in receiving an HIV test and the risks that participants identified in participating in a study about HIV, the 2002 pilot study provided an impetus and justification for a subsequent observational HIV prevalence study.

Figure 1.

Timeline for HIV testing and treatment in Moshi, Tanzania.

Observational Study of HIV and Other STIs, 2004

Together with a team of Tanzanian researchers, AN returned to TSE in 2004, using an observational study design, to assess how the unique context of life on an agricultural plantation influences sexual behavior and risks for several STIs: HIV, syphilis, and herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2). The methods for this observational study are well described elsewhere (Norris 2009). In summary, the team used a mobile research unit to administer a questionnaire, offer counseling and testing for STIs, and perform rapid laboratory assessments of HIV. Participants used Audio Computer Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) on laptop computers to self-report sexual behavior. HIV testing was done at the time of the interview using two rapid tests (Determine and Capillus); syphilis and HSV-2 tests were conducted weekly at a separate location using stored serum. The observational study was reviewed and approved by five independent ethical review committees: one in the United States (Yale University Human Investigation Committee) and four in Tanzania (the Tanzanian National Institute of Medical Research, the Tanzanian Commission on Science and Technology, the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center Ethics Committee, and the TSE Ethics Committee).

All participants received 1 kilogram of rice (worth US$2) in exchange for participation in the study. This incentive was provided for all who participated in the questionnaire portion; participation in the STI testing was not required to receive the rice incentive. The research team provided free counseling and testing for HIV (valued at US$2), syphilis (US$2), and HSV-2 (US$4). Participants with positive STI test(s) received free referral for HIV care, treatment for syphilis (US$1), and/or treatment for active HSV-2 (US$5). In consultation with local IRB committees, the team determined that rice, while appreciated as a gift, had a low enough value to preclude creating undue influence. STI counseling and testing were research procedures that had collateral benefits to participants. The research team did not offer any social or medical services to participants except for treatment for syphilis and active HSV-2.

Of 333 randomly selected participants, 270 (81%) agreed to complete the questionnaire, and of these, 197 (73%) agreed to have blood drawn and tested for STIs, including HIV. More than 350 community members who were not randomly selected asked to take part in the study. Overall, combining the randomly selected participants with the self-volunteered participants, HIV prevalence was 6%, syphilis 8%, and HSV-2 was 56% (Norris 2006).

In 2006, AN and her Tanzanian team once again returned to TSE to examine and evaluate the consequences and ethics of the 2004 observational study. We consider now the application of international standards of research ethics to the observational study in Tanzania just described. For an evaluation of the relative meaning of these standards in the Tanzanian context, see Hellsten’s (2005) thoughtful review.

Ethical Principles of Research Involving Human Subjects

In its International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects, the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) provides clear and detailed guidance for international research, with particular attention to the ethical conduct of research in developing countries. CIOMS described three principles of bioethics: (1) respect for persons/autonomy; (2) beneficence/nonmaleficence; and (3) distributive justice. While CIOMS states that these principles apply to both intervention trials and observational research, the guidelines heavily emphasize their application to intervention trials (CIOMS 2002). We describe here the three principles of research ethics that provide a framework for evaluating the ethics of the 2004 observational study.

Respect for Persons/Autonomy

Respect for persons incorporates the fundamental ethical consideration of autonomy, which “requires that those who are capable of deliberation about their personal choices should be treated with respect for their capacity for self-determination” (CIOMS 2002). In consideration of autonomy, the CIOMS guidelines state that researchers must make provisions to respect the participants’ privacy and maintain the confidentiality of their information (CIOMS 2002). For example, qualitative research in South Africa found that stakeholders in HIV vaccine trials expressed doubts that confidentiality is always maintained when the participants and researchers live in the same community. On the other hand, the South African study also found that stakeholders are sometimes suspicious of strict adherence to privacy and confidentiality, as it leads them to wonder whether the researchers are hiding secret or shameful experimentation (Essack 2010).

In addition, CIOMS guidelines require researchers to provide participants with adequate information about the risks, benefits, duration, purposes, results, implications, products, and sponsorship of the study in order to ensure the voluntariness of participation (CIOMS 2002). Informed consent is a vital mechanism for ensuring autonomy, since it protects the individual’s freedom of choice. In developing countries, it may be difficult to obtain uncoerced, meaningful informed consent due to constraints in language and culture, as well as the influence of power and authority wielded by researchers (Benatar 2001). Informed consent may be further compromised by differences between researchers and participants in comprehension of information, perceptions of risk, and views of decisional authority (Marshal 2006).

Beneficence and Nonmaleficence

Researchers have an ethical obligation to maximize benefits and minimize harm to study participants. In order to do this, the research design must be sound and the researchers must be competent to carry out the study and protect the welfare of the participants (CIOMS 2002).

CIOMS published a separate set of guidelines for the ethical conduct of epidemiological studies, including observational studies. CIOMS outlines several ways that researchers can maximize benefits, three of which apply to observational studies: Researchers must communicate study results to participants and relevant health authorities; researchers must provide health care or referral to local health services while researchers are present; and researchers must train local health personnel so that something of value is left after researchers depart (CIOMS 1991).

Nonmaleficence specifically refers to the requirement that researchers not deliberately inflict harm on participants, as captured in the standard “do no harm” (CIOMS 2002). For epidemiological studies, including observational studies, common risks that researchers must minimize for individual participants include stigmatization, prejudice, loss of prestige or self-esteem, and economic loss as a result of study participation. In addition, risks for groups can include economic loss, stigmatization, blame, or withdrawal of services—especially if the researchers’ presentation of study results implies moral criticism of participants’ behavior (CIOMS 1991).

The ethical requirements for beneficence and nonmaleficence are more developed for intervention trials. It is widely accepted that participants in HIV/AIDS treatment trials deserve continuing posttrial access to treatment, especially since interruption of antiretroviral therapy can cause harm, such as drug resistance (Lo 2007; Macklin 2006). Many argue that participants who seroconvert during HIV prevention trials should also have access to treatment when they develop AIDS (Lo 2007; Macklin 2006). Some have based the justification for treatment access for those who seroconvert during HIV prevention trials on the principle of nonmaleficence: Some participants in HIV prevention trials may have increased their risk behaviors and acquired HIV during the trial because they believed that the intervention, such as a vaccine candidate or microbicide, was effective. Thus, they should be given treatment to compensate partially for a harm—HIV infection—that may have been research related (Schüklenk 2000). In observational research, since HIV infection could not be considered a research-related injury, the argument for providing treatment to participants who test positive would have to be made on other grounds, such as the obligation to provide ancillary services to participants.

Distributive Justice

The National Bioethics Advisory Commission recommends achieving “equitable distribution of the burdens and benefits of research” (NBAC 2001, Recommendation 1.1). In The Belmont Report, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1979) advised, “The selection of research subjects needs to be scrutinized in order to determine whether some classes (e.g., welfare patients, particular racial and ethnic minorities, or persons confined to institutions) are being systematically selected simply because of their easy availability, their compromised position, or their manipulability, rather than for reasons directly related to the problem being studied.”

In order to ensure fair distribution of the benefits of research, efforts should also be made not to exclude groups or classes of people from research participation. The Declaration of Helsinki, Ethical Principle 5, states, “Medical progress is based on research that ultimately must include studies involving human subjects. Populations that are underrepresented in medical research should be provided appropriate access to participation in research” (World Medical Organization 1996, 1448).

Furthermore, CIOMS Guideline 10 deals with research in populations and communities with limited resources. The guideline instructs researchers to ensure that “the research is responsive to the health needs and the priorities of the population or community in which it is to be carried out; and any intervention or product developed, or knowledge generated, will be made reasonably available for the benefit of that population or community” (CIOMS 2002). Research should reflect the needs of the community, and the findings must benefit that community as well.

We note one important dilemma, faced in particular by investigators who choose to carry out observational studies in underresourced setting with few ancillary or referral services. The underlying tenet of fulfilling distributive justice is that these populations should be given access to participation in research. In these settings, however, researchers may face an impossible responsibility to attend to all the “ancillary” service needs of the study population (e.g., those needs that fall outside the scope of the study, such as housing, food, and medical care) and thus fail to fulfill the principle of beneficence. Considering observational research in particular, researchers must acknowledge that while the research findings could eventually benefit members of the community, neither the researchers nor the existing services may be reasonably able to provide care for those identified as needing care.

The guidelines just described provide thoughtful and specific recommendations so that researchers can conduct ethical research. CIOMS Guideline 8 instructs investigators to “ensure that potential benefits and risks are reasonably balanced and risks are minimized.” We examine the case of the 2004 observational study at TSE, considering participants’ individual and community-level experiences, to assess whether the study appropriately provided benefits and safeguarded against risks. We examined the 2004 study to ask: How well did the study ensure respect for persons, beneficence/nonmaleficence, and distributive justice? With this analysis, we address an underexplored area in research ethics: the effects of observational research on participants and communities.

METHODS

From June through August 2006, the lead author (AN) worked at TSE with a team of six Tanzanian researchers to explore the ethical ramifications of the 2004 study. All team members were fluent in Swahili, were familiar with the TSE context, and had received training in the ethical conduct of research. The team members were the same women and men who had been trained and participated in the 2004 study.

Part of the motivation for the return to TSE was to disseminate research findings from the 2004 observational study. Dissemination was accomplished via several formal presentations with hospital workers, plantation administration, and community leaders. Quantitative and qualitative research findings were presented, and each presentation was followed by a lively discussion, during which audience members asked questions and commented on the research method, study findings, and researchers’ conclusions. To share findings with plantation workers and their families, the research team created and distributed a short documentary film that was shown throughout the camps. Members of the research team recorded field notes from the comments, questions, and discussions that followed both the formal presentations and film screenings.

The team also recorded field notes from 15 in-depth interviews with hospital workers, plantation administrators, and community leaders. Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to the interviews. We utilized an open-ended question guide for in-depth interviews, asking interviewees their thoughts about positive and negative consequences for participants and the community as a result of the research. We asked how the research could have been conducted better, and how the research results could be used.

Finally, the research team recorded notes from their own observations and informal conversations with approximately 50 community members, some of whom were participants in the 2004 study. Participation in the 2004 study was not a criterion for inclusion in the current ethics evaluation.

The three sets of researcher field notes—from discussions following formal and film presentations, in-depth interviews, and observations/informal conversations—constitute the qualitative data utilized in this evaluation. Field notes were written in Swahili and English; translations were done by the authors. The data were hand coded for analytic categories, and the data analysis was guided by the principles of grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Strauss and Corbin 1990).

This ethical evaluation was reviewed and deemed non-human subjects research by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee because participants were sharing their opinions and insights about the 2004 study, not providing information about themselves. No incentives were provided, and no identifying data were collected.

RESULTS

Respect for Persons/Autonomy

Voluntary Participation

In the 2004 observational study, the researchers took special measures to ensure that participation in the observational study was voluntary. Before recruiting participants, the research team held camp-wide community meetings to introduce themselves and the study. Advance notice gave camp residents the opportunity to consider participation and discuss the study with others before volunteering to become participants. After these community meetings, many who learned about the study but who were not randomly selected asked to participate. The research team welcomed all persons who met eligibility criteria to participate, and dis-aggregated the data by whether or not the participants were randomly selected.

The researchers also discussed the voluntary nature of the study at each point of contact with all potential participants: introducing the study, recruiting each selected participant at home, during the first informed consent for the interview, during pretest counseling, and during the second informed consent for STI testing. Informed consent procedures were identical for all participants, randomly sampled and self-volunteered. Given the highly hierarchical nature of this workplace setting, researchers repeatedly emphasized that the research team members were not part of the company that owns TSE but rather researchers affiliated with the large medical center in nearby Moshi. Further, the team reminded everyone that no individual results would be shared with the company or with anyone else.

This multiple verification of participants’ right to refuse was important: Many expressed relief that researchers did not insist on testing. One community member explained that “at first, people were worried that the company was involved, but later they came to understand that you weren’t with the company.” Gaining the trust and respect of local leaders within the camps was vital to the success of the study, as these leaders would vouch for the research team when other community members asked about the study.

For some members of the community, the team’s strict adherence to noncoercion made the study results less believable. A number of people in the random sample declined to participate, so some people reasoned that the findings were not representative of the community. Others noted that self-selection could have biased the results: “I went to test to be sure I didn’t have it. The sick ones stayed at home.” Some felt that, for the results to be valid, the study would have to test every person at TSE. A TSE staff member said, “It seemed that the sample was determined by the researchers,” suggesting that some thought the sample was not representative.

Further complicating the issue of representativeness, many community members did not grasp the utility of randomization. Some who were selected felt targeted; others who were not selected felt excluded. Many thought that randomization was an unnecessary complication, and the research should simply include only those who sought out participation in the study. The concept of randomization is not intuitive, and in the end the team succeeded in convincing people that the system of randomization was fair, even if the team was not able to convince them of its usefulness.

Confidentiality

The research team attempted to explain the confidential nature of the study in culturally appropriate ways: Instead of using the Swahili word siri (“secret”), which connotes shame and implies that people are not at liberty to share their own results, the research team members simply said that they would not report any results to anyone unless the participant asked them to do so. To our knowledge, confidentiality was maintained throughout the observational study. A health administrator for TSE, among others, noted that there were “no breaks in confidentiality.” A research team member received the following report about the lead researcher: “She did her work well and carefully, kept things confidential.”

One factor that may have helped the study maintain confidentiality was that the researchers came from outside the TSE community; all of them lived in the nearby town of Moshi and were not employed by TSE. The participants came to understand that the study was led by a Swahili-speaking American, and that the Tanzanians on the team were not from their own community. Community members thought the researchers were less likely to gossip about them. “The researchers were from the outside—this helped for those who were afraid,” said a TSE health worker. In addition, a community leader explained that once people understood that the researchers were not part of the TSE management, people had less fear that either nonparticipation or positive HIV/STI test results could lead to termination of employment.

Ironically, the rigor of confidentiality reduced the credibility of the study in the eyes of some community members. During the 2004 observational study, and in the 2006 follow-up, research team members were challenged: “Are you telling people their real results? If you are, then why haven’t we heard that anyone is positive?” Some community members believed that the researchers were telling HIV-positive participants that they were HIV-negative to keep participants happy and ensure the continuation of the study. To prove their point, community members described carefully observing others in the interview and testing process, from afar: “There, now she’s doing the computer—There, now she’s getting her results—Now! Look at her laughing happily in the road.” Some community members were sure that if anyone had been given a positive result, others would have known. Thus, some in the community might have found the overall study results more believable if there had been breaches of confidentiality that revealed some participants to be HIV-positive.

Although the confidentiality of results was maintained, it was not possible to completely conceal who participated in the study, since others could see participants enter and exit the research tents. A community member said, “Men don’t take research or advice. So they were mad at their wives for participating. Some were beaten.” While this claim was not substantiated through other reports, we mention it to highlight the potential for unanticipated harms resulting from observational studies, particularly those that involve biological testing for stigmatized diseases and behaviors.

Beneficence and Nonmaleficence

For some of the study participants who tested negative for HIV, the benefits of participation included relief and renewed motivation to protect themselves from HIV. One health worker said:

“Those who were HIV-negative were very happy. They had been afraid, as they knew TSE was a ‘high transmission’ area and they were so happy when they were tested and found to be negative. We at the hospital were also happy. We assumed that the rate would be above 10%. We assumed it was a high transmission area.”

Some participants said the study helped them overcome fatalism about HIV/AIDS and take measures to reduce their HIV risk; one man explained that he had had five lovers before, but left them to be faithful to his spouse once he found out he was HIV-negative. Since the study was not designed to measure behavior change, the overall impact of HIV testing on behavior cannot be assessed.

The study provided an immediate benefit of STI diagnosis and treatment to participants who were found to have syphilis and active HSV-2. For those who tested positive for HIV, in addition to knowing their HIV status, study participation included the opportunity to learn about avoiding transmission of the virus, ways to promote living well with HIV, and antiretroviral treatment in Moshi. The research team ensured that participants received referrals to support and care services, though the team did not facilitate connections to these services, so as to protect the confidentiality of the participants.

Before the 2004 observational study, TSE’s management would not commit to providing treatment without knowing the size of the problem. Due to limitations of the study scope, time frame and budget, the research group made it clear to participants that the study would not provide HIV treatment. In 2004, antiretroviral therapies were starting to become available in Moshi, though free treatment was in limited supply and paying for treatment was prohibitively expensive for most people.

Returning to TSE in 2006, research team members did not specifically seek out interviews with the 32 participants who had tested positive for HIV in the 2004 observational study. However, anecdotes collected by the team indicated that, at least for some, learning one’s HIV status carried negative consequences, such as emotional distress. A Tanzanian member of the research team recalled the following incident from a visit to TSE in 2005:

“One woman told me about her sister-in-law, who was found to be HIV-positive in the study … The woman was afraid that if her husband found out she was HIV-positive, he might kill her, and he had already killed someone. She was on HAART … She was using condoms, telling her husband it was for ‘family planning.”’

By learning her HIV status, this participant was able to start on lifesaving medications, and at the same time, was afraid of the consequences if her husband were to learn about her status.

In another incident, a team member at TSE during the ethics evaluation came across a man hoeing in his field by himself. “Have you come to test again?” he called to the researcher. She stopped to talk to him. Speaking angrily, and waving his hoe, he said, “You left us at njia panda (a fork in the road).” When she was confused, he said “Don’t you know me? I’m finished [implying that he will die from AIDS], my wife is finished.” She asked him to put down his hoe and talk to her. She explained that medicine was now available at the TSE hospital, and suggested that he go there. “No! Our neighbors will look at us!” he yelled. Clearly, there were painful consequences on the part of some participants who tested positive for HIV. Some community members said the researchers should have provided more counseling, especially couples counseling, to those who were HIV-positive.

The issue of disclosure was a particularly important issue when partners were HIV-discordant. While the research team offered couples testing, and offered to counsel participants’ partners, few participants accepted. A TSE health worker pointed out negative consequences for discordant couples: “For those who were HIV positive, some separated from their spouses. They fought, divorced each other, rejected each other. Some needed more counseling for the couple to communicate.”

The study’s effect on people who turned out to be HIV-positive is central to understanding if the ethical obligations of benefice and nonmaleficence were met. A community member who is active in a local HIV nongovernmental organization was asked, “Were there any bad results for people who participated?” She answered, “Those people who were HIV-positive were very upset after getting home.” In response to the next question, “Were there any benefits from our research?,” she answered, “Those who were HIV-positive got education, counselors, and connections to [nongovernmental organizations, NGOs] to lengthen their lives—and they are still alive. Those people won’t leave orphans soon.” Thus, we see that while receiving a diagnosis of a potentially deadly illness was hard for participants, that diagnosis provided an overall positive benefit in their lives.

Distributive Justice

The TSE community is an understudied population. The 2004 observational study aimed to add to the scant knowledge on the sexual health of agricultural workers in general and those at TSE in particular. In addition, the study aimed to collect data that would help the TSE community and other communities like them where HIV and other STI testing was not available but desired. TSE was selected for reasons directly related to the problem being studied—HIV/AIDS and STIs—rather than factors like easy availability or manipulability of the population. Since community members had expressed concerns about HIV and a desire for HIV testing, conducting the 2004 study at TSE provided an underserved community’s members the opportunity to participate in research that could help them address a self-identified problem. Many community members in the 2004 observational study participated as volunteers, which we see as further evidence that the study was desired by community members. The 2004 observational study, responding to a community-identified need for testing, even in a context where treatment was not readily available for HIV, arguably met the ethical obligation of distributive justice.

The positive effects of the study on the community provide further evidence that distributive justice was achieved. The study provided a forum for learning about HIV/AIDS at a time when the availability of testing and treatment were changing. Health care workers described changes they attributed to the observational study:

“The results really brought great motivation. It motivated us! The HIV level is not such a big percentage as we thought. It is our time now to increase efforts to encourage people to protect themselves against unprotected sex, alcohol, and promiscuity.”

Other community leaders made statements about changes they have seen in behavior throughout the community:

“People have their eyes open now. They care about themselves and their status. It was different before; people didn’t understand how to prevent—now they use more prevention.”

“The big change is that now people feel free to test for HIV. They learned “Oh, if I test, I might be negative!”

Some leaders’ comments speak about change at the level of community norms:

“In mosques, churches, schools, it is now normal to talk about HIV.”

“Before, they were afraid of HIV positive people … It used to be that if someone was suspected of being HIV positive they would be stigmatized or mocked. Now even when they know someone is positive, they take care of each other.”

Summary Assessment

The 2004 observational study did, of course, come to an end, after 10 months of interaction with plantation residents. Subsequent to the study’s conclusion, HIV testing became more common at TSE. Although some people continued to have concerns about confidentiality of HIV testing at the TSE hospital, more opted to test there, likely due to three changes: an increased understanding of HIV testing, the availability of HIV treatment at the TSE hospital, and the initiation of “opt out” testing for women seeking prenatal care at the TSE hospital.2 While some local researchers and care providers were interested in continuing the mobile testing in communities near TSE, none had the resources necessary to do this.

Overall, it is difficult to know which changes in knowledge, attitudes, and behavior are attributable to the presence of the 2004 observational study. As one TSE health worker explained, “We can’t say there was change just because of the research. There were lots of other things going on about HIV, such as hospital campaigns and groups that contribute to education.” Research takes place in a changing context.

The observational study took place during a key time in the plantation management’s decisions about HIV treatment. A few months before the observational study began in 2004, the TSE hospital had begun providing antiretroviral therapy to HIV-positive patients, but the service was quickly shut down by the TSE management, which cited insufficient information and resources necessary to implement long-term and potentially costly care. According to a company health worker, the observational study’s finding that 6% of study participants were HIV-positive made the management less fearful that the problem was insurmountable. Coincident with help from the government to provide care and treatment, the TSE administration developed an HIV/AIDS Care and Treatment Center at the TSE hospital in 2006.

DISCUSSION

While the original 2004 observational study was explicitly observational, and not an intervention trial, we suspected that the study may have had intervention-like effects in this setting where testing for HIV and other STIs had previously not been readily available. We therefore wished to evaluate the consequences of such a de facto HIV-testing intervention, and ask more broadly: What obligations do observational studies have to their participants? Using the core ethical principles that guide human subjects research—respect for person/autonomy, beneficence/nonmaleficence, distributive justice—to frame our inquiry, we contribute to the scant literature about the consequences, and responsibilities, of observational studies. We argue that particularly for an observational study that includes biological testing for a stigmatized disease, such research can include elements of an intervention study in ways that are often overlooked and not appreciated by the investigators. The ethical issues that are usually associated with an intervention study become important and merit consideration.

The links and tensions among the three ethical principles must be considered when investigators apply them, particularly in studies that take place in resource-limited settings. We identified areas in which ethical principles were in conflict, or, in other words, areas in which meeting one ethical obligation was incompatible with another ethical obligation. The potential ethical trade-offs are of particular interest where the consequence of fulfilling one ethical obligation impinges on fulfilling another. The three overarching principles are often considered to have equal moral force, but in practice, especially in resource-limited settings, researchers may have to prioritize one or more of them over the other(s).

For example, beneficence may have been compromised by the commitment to another ethical concern. Because of respect for persons and confidentiality (and a particular concern about the reputation for poor confidentiality at the TSE hospital), the observational study used researchers from outside the TSE community. One health care provider at TSE noted a drawback to this: If TSE’s health care staff had been involved in the research, then

“patients would have become used to them. When the patients came to the hospital they wouldn’t have to redo testing. Now [the health care providers] have to redo the process of getting to know the patients. There is a lot of waste in… . manpower, supplies, time and effort.”

Due to confidentiality concerns, the research team never returned to the homes of participants after their participation. While this did preserve confidentiality, and eliminated gossip about potential test results of any participants, it limited the researchers’ ability to provide benefits in the form of ongoing support to participants, including additional information about services at the plantation or in the town of Moshi. Thus, in the interest of maintaining both confidentiality and the appearance of confidentiality, the team may have compromised opportunities for care for those who were diagnosed with HIV or other STIs in the study. Some TSE health care workers complained that there was a lack of continuity of care for study participants who tested positive for HIV or other STIs; they “had to start all over again when they came to the hospital.” Thus by protecting participants’ confidentiality (respect for persons), the research team did not provide some HIV-positive participants with satisfactory HIV care services (beneficence).

By maintaining confidentiality and ensuring noncoerced participation (respect for persons), the study team reduced the community’s belief in the validity of study findings (distributive justice). Greater acceptance of the study results in the community might have led to greater positive changes in behavior at a community level, thereby benefitting the community. While we hold that it is more important to maintain confidentiality, we acknowledge that the utility of the study findings to the community was reduced by securing the ethical obligation of respect for persons to individual participants.

Emanuel, Wendler, and Grady (2000), in their excellent summary of ethical requirements of clinical research, acknowledge that “some tensions, if not outright contradictions, exist among the provisions of the various [research ethics] guidelines” (Emanuel 2000, 2702). Five of Emanuel, Wendler, and Grady’s seven requirements of ethical research are based on the principles we considered, but like the CIOMS recommendation, they focus on the obligations of clinical, or intervention, research (Emanuel 2000). Our evaluation builds on their work, identifying how these ethical requirements apply to observational research, and high-lighting ways that the ethical requirements themselves, and not simply the guidelines that describe them, may come into conflict.

We note that several aspects of the 2004 observational study ensured that researchers were able to meet obligations to participants. The study benefitted from high-level of community involvement, relatively long duration (with a pilot study in 2002 and 10 months of data collection in 2004), and researchers who spoke Swahili. By leading community information meetings in Swahili, the research team reassured participants that they could understand the objectives of the study and trust the research team. Marshall (2006) notes that

“comprehension is always enhanced when researchers engage the study community in active discussions of project goals and procedures through meetings with local leaders or public forums, and when information is provided to potential participants before obtaining consent.” (25)

Despite this relatively deep engagement with the community, community members would have liked more, proclaiming: “We were just getting used to you when you left!” It takes time for researchers to gain participants’ trust. With more involvement and over a longer duration, more participants would have come to believe the commitment to nonmaleficence, to trust that the team was doing all it could to prevent potential negative consequences of participating in the study. Studies that, for the sake of efficiency, put less time into developing a trusting relationship with the community are at risk for poor participation and other problems.

Our evaluation of an observational study of HIV testing is relevant to a broader literature. Ethicists and epidemiologists alike have examined the impact of testing for HIV infection. Ethicists have explored the right to refuse to be told test results (Temmerman 1995) and the quandary of testing when treatment is not available or substandard (Frey 2003). Epidemiologists have studied whether voluntary HIV counseling and testing is a successful strategy to promote safer sex and prevent HIV. While there is some evidence that people who learn they are seropositive for HIV subsequently adopt safer behaviors (avoiding spreading HIV to others), there remains debate about the effect on people who learn they are HIV-negative. For example, a randomized controlled trial in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad found that HIV-negative participants reported safer sexual practices more than a year after learning their status, as compared to participants who did not receive an HIV test (Voluntary HIV-1 Counseling and Testing Efficacy Study Group 2000). However, other researchers report that individuals who test negative for HIV do not sustain behaviors to reduce risk, and may adopt riskier behaviors, as though the test provided “proof” that the behaviors they engaged in already were safe (Ryder 2005). Biehl et al. (2001) address a different negative aspect of testing: the phenomenon of “imaginary AIDS,” where low-risk clients experience anxiety and complain of AIDS-like symptoms when they go for an HIV test. These thoughtful assessments of the consequences of HIV research have not, however, considered the ethical consequences of the research itself.

Recommendations

To meet the ethical requirement of respect for persons/autonomy, we recommend that observational studies include sufficient time and community involvement to ensure individuals understand the voluntary nature of participation. While high rates of participation are preferred for observational studies in the interest of having representative findings, this aim must be balanced with the ethical obligation of respect for persons/autonomy. To reduce problems that may arise from differences in language, perception of risk, and understandings of decisional authority, a thoughtful and comprehensive engagement with the community is needed.

We further recommend that all studies, including observational studies, should develop postresearch plans. While the Declaration of Helsinki and CIOMS are silent on postresearch obligations for observational studies, we posit that observational studies also have postresearch obligations to study participants. In the event that the researchers will not return to the study site, researchers need to anticipate participants’ postresearch needs and make plans with partners and stakeholders who will be able to share the results of the study and to provide participants with supportive services beyond the period of data collection (Emanuel, Wendler, and Grady 2000). Finally, observational study researchers may fail to realize the extent to which their work takes place in the context of many forces of change. While extremely rare in practice, particularly for observational studies, returning to the study site to share study findings is scientifically useful. Researchers can understand their results in a fuller context over time, and reconnecting with the study site and participants better informs conclusions about the impact of the work.

CONCLUSION

Research projects that are not designed as interventions may change the way that people think about issues directly connected to their health and social well-being, and may serve, therefore, as an intervention. These de facto interventions may occur on the individual level; we found also that community-level benefits may accrue from a study if it provides any testing for infections or services, and if the study results are shared and discussed with the community. Observational studies thus share many of the same obligations for respect for persons, beneficence and nonmaleficence, and distributive justice as intervention studies. While we recognize that researchers cannot anticipate all impacts their research may have on participants, those carrying out observational studies should acknowledge that their work may have important consequences, and should consider the ethical dimensions of these consequences.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge intellectual and financial support from the Donaghue Initiative in Biomedical and Behavioral Research Ethics of the Yale Interdisciplinary Center for Bioethics. Research funding for Alison Norris was also generously provided by Yale’s Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, the Fulbright Fellowship for Doctoral Research Abroad, the Yale Center for International and Area Studies, and the Ellertson Social Science Fellowship in Reproductive Health. We are grateful to the workers, residents, and administrative staff at TSE for their engagement with our work, to Dr. Sabina Mtweve for guidance and support, and for their dedication and insights to members of the research team: Elizabeth Urio, Michael Ndonde, Edina Ngowi, Max Mushi, Ngaya Harison, William Maro, Matilda Mrawa, Mary Shirima, Ndealilia Swai, and Julie Ulomi. We especially recognize the valuable contributions of Amani Kitali and Abu Mfundo in the gathering of field data.

Footnotes

TSE is a pseudonym.

“Opt out” HIV testing is a way of delivering voluntary HIV counseling and testing as part of routine health care. At TSE, initiation of “opt out” testing meant that women attending the TSE clinic for prenatal care would be told that HIV counseling and testing is provided routinely, and that if they do not wish to be tested, they can “opt out” and will not be tested. “Opt out” differs from an “opt in” paradigm, in which testing is offered and the patient is required to actively give permission before it can occur. “Opt out” has become standard of care in many settings because people can more easily agree to HIV counseling and testing when it presented as a part of regular care, rather than a special service to accept.

Contributor Information

Alison Norris, Ohio State University.

Ashley Jackson, Independent Researcher.

Kaveh Khoshnood, Yale School of Public Health.

REFERENCES

- Benatar S. Distributive justice and clinical trials in the third world. Theoretical Medicine. 2001;22:169–176. doi: 10.1023/a:1011419820440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biehl J, Coutinho D, Outeiro A. Technology and affect: HIV/AIDS testing in Brazil. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2001;25(1):87–129. doi: 10.1023/a:1005690919237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan D, Khoshnood K, Stopka T, Shaw S, Santelices C, Singer M. Ethical dilemmas created by criminalization of status behaviors: Case examples from ethnographic field research with injection drug users. Health Education and Behavior. 2002:29–41. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences . International guidelines for the ethical review of epidemiological studies. CIOMS; Geneva, Switzerland: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences in collaboration with the World Health Organization . International ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects. CIOMS and WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel E, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(20):2701–2711. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.20.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English A. Runaway and street youth at risk for HIV infection: Legal and ethical issues in access to care. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12(7):504–510. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(91)90078-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essack Z, Koen J, Barsdorf N, et al. Stakeholder perspectives on ethical challenges in HIV vaccine trials in South Africa. Developing World Bioethics. 2010;10(1):11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2009.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey S. Unique risks to volunteers in HIV vaccine trials. Journal of Investigative Medicine. 2003;51(suppl. 1):S18–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine; Chicago, IL: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Grusky O, Roberts K, Swanson A, et al. Anonymous versus confidential HIV testing: Client and provider decision making under uncertainty. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2005;19(3):157–166. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenter D, Esparza J, Macklin R. Ethical considerations in international HIV vaccine trials: Summary of a consultative process conducted by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Journal of Medical Ethics. 2000;26(1):37–43. doi: 10.1136/jme.26.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne W, Siegel L. Should there be HIV testing in chemical dependency treatment programs? Advances in Alcohol & Substance Abuse. 1987;7(2):15–19. doi: 10.1300/j251v07n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellsten S. Bioethics in Tanzania: Legal and ethical concerns in medical care and research in relation to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 2005;14:256–267. doi: 10.1017/s0963180105050358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern S. HIV testing without consent in critically ill patients. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294(6):734–737. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajeski J. Legal, ethical, and public policy issues. New Directions for Mental Health Services. 1990;48:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine R, Gorovitz S, editors. Biomedical research ethics: Updating international guidelines. A consultation. CIOMS; Geneva, Switzerland: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lo B, Padian N, Barnes M. The obligation to provide anti-retroviral treatment in HIV prevention trials. AIDS. 2007;21:1229–1231. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281338371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklin R. Changing the presumption: Providing ART to vaccine research participants. American Journal of Bioethics. 2006;6(1):W1–W5. doi: 10.1080/15265160500394978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall P. Special Topics in Social, Economic and Behavioural Research report. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2006. Ethical challenges in study design and informed consent for health research in resource-poor settings. (series, No. 5). [Google Scholar]

- Mfutso-Bengo J, Muula A. Ethical issues in voluntary HIV testing in a high-prevalence area: the case of Malawi. South African Medical Journal. 2003;93(3):194–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Bioethics Advisory Commission . Report and recommendations. Vol 1. National Bioethics Advisory Commission; Bethesda, MD: 2001. Ethical and policy issues in international research: clinical trials in developing countries. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Bioethics Advisory Commission . Commissioned papers and staff analysis. Vol 2. National Bioethics Advisory Commission; Bethesda, MD: 2001. Ethical and policy issues in international research: clinical trials in developing countries. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research . The Belmont report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Office of the Secretary, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Washington, DC: 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris A, Kitali A, Worby E. Alcohol and transactional sex: How risky is the mix? Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69:1167–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris A. Doctoral dissertation. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 2006. Sex and society: Determinants of prevalent HIV, syphilis and HSV-2 among Tanzanian sugar plantation residents. [Google Scholar]

- Piot P. Screening and case finding in the prevention and control of STDs and HIV infection. In: Paalman M, editor. Promoting safer sex: Prevention of sexual transmission of AIDS and other STDs. Swets & Zeitlinger; Lisse, Netherlands: 1990. pp. 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder K, Haubrich D, Calla D, Myers T, Burchell A, Calzavara L. Psychosocial impact of repeat HIV-negative testing: A follow-up study. AIDS Behavior. 2005;19:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9032-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüklenk U, Ashcroft R. International research ethics. Bioethics. 2000;14:158–172. doi: 10.1111/1467-8519.00187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar A, Pisal H, Patil O, et al. Women’s acceptability and husband’s support of rapid HIV testing of pregnant women in India. AIDS Care. 2003;15(6):871–874. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001618702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr L, Bergenstrom A, Hudson C. Consent and ante-natal HIV testing: The limits of choice and issues of consent in HIV and AIDS. AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):307–312. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Should developing countries be testing grounds for vaccines rejected by the USA? AIDS Analysis Africa. 1994;4(4):2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegal H, Carlson R, Falck R, et al. Conducting HIV outreach and research among incarcerated drug abusers: A case study of ethical concerns and dilemmas. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 10(1):71–75. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90102-8. 2993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Temmerman M, Ndinya-Achola J, Ambani J, Piot P. The right not to know HIV-test results. Lancet. 1995;345(8955):969–970. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90707-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom R. HIV/AIDS and mental illness: Ethical and medico-legal issues for psychiatric services. South African Psychiatry Review. 2003;6(3):18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Uganda gets set for vaccine trials, but the ethical debate continues. AIDS Analysis Africa. 1997;7(2):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voluntary HIV-1 Counseling and Testing Efficacy Study Group Efficacy of voluntary HIV-1 counseling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: A randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9224):103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. British Medical Journal. 1996;313(7070):1448–1449. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington C, Myers T. Factors underlying anxiety in HIV testing: Risk perceptions, stigma, and the patient-provider power dynamic. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13(5):636–655. doi: 10.1177/1049732303013005004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]