Abstract

Objective

The level of adherence to guidelines should be explored particularly in preterm infants for whom poor nutrition has major effects on outcomes in later life. The objective was to evaluate compliance to international guidelines for parenteral nutrition (PN) in preterm infants across neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) of four European countries.

Design

Clinical practice survey by means of a questionnaire addressing routine PN protocols, awareness and implementation of guidelines.

Setting

NICUs in the UK, Italy, Germany and France.

Participants

One senior physician per unit; 199 units which represent 74% of the NICUs of the four countries.

Primary outcome measure

Adherence of unit protocol to international guidelines.

Secondary outcome measure

Factors that influence adherence to guidelines.

Results

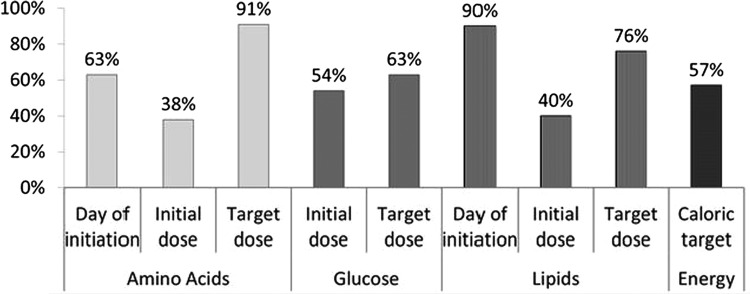

80% of the respondents stated that they were aware of some PN clinical practice guidelines. For amino acid infusion (AA), 63% of the respondents aimed to initiate AA on D0, 38% aimed to administer an initial dose ≥1.5 g/kg/day and 91% aimed for a target dose of 3 or 4 g/kg/day, as recommended. For parenteral lipids, 90% of the respondents aimed to initiate parenteral lipids during the first 3 days of life, 39% aimed to use an initial dose ≥1.0 g/kg/day and 76% defined the target dose as 3–4 g/kg/day, as recommended. Significant variations in PN protocols were observed among countries, but the type of hospital or the number of admissions per year had only a marginal impact on the PN protocols.

Conclusions

Most respondents indicated that their clinical practice was based on common guidelines. However, the initiation of PN is frequently not compliant with current recommendations, with the main differences being observed during the first days of life. Continuous education focusing on PN practice is needed, and greater efforts are required to disseminate and implement international guidelines.

Keywords: Neonatology, Nutrition & Dietetics

Article summary.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Nutrition for preterm infants is a hot topic in the field of neonatology.

A large survey in four European countries that included 74% of the units of the four countries.

The survey reflects one of the first steps in the dissemination of guidelines and thus provides insight on compliance to guidelines.

The survey reflects the intention to treat of the personnel from the neonatal intensive care units that responded to the survey, and may not reflect the actual clinical practice within the unit.

Introduction

Poor nutrition in preterm infants has major effects on outcomes in later life, including physical growth, intellectual development and, possibly, cardiovascular and metabolic effects.1 2 The quality and quantity of daily nutritional intake are critical, particularly during the first weeks of life, since amino acid, energy and lipid intake from parenteral nutrition (PN) have been shown to be associated with later development.3 4 Reports from neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) worldwide have shown that nutritional intake in preterm infants is inadequate.5 6 The causes of this inadequate intake, particularly in the early neonatal phase, may be multifactorial and partly iatrogenic. It may depend not only on the infant's metabolic capacities, but also on the availability and safety of the solutions used, the type of venous access, the department's usual practice and the prescriber's knowledge of the infant's nutritional needs.7

Clinical practice guidelines for the nutritional needs of preterm infants have been regularly revised over recent decades, leading to the development of the most recent international guidelines on paediatric PN in Europe from the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) in 2005,8 and globally in the book entitled ‘Nutritional needs of the preterm infant: Scientific basis and practical guidelines’ also published in 20059 (table 1). Previous studies, especially those performed before the current clinical practice guidelines were available, demonstrated large differences in the nutritional protocols applied in clinical practice and the resulting clinical outcomes.6 10 11 A recent systematic review showed that large differences are observed in the nutritional protocols among NICUs in the individual surveys and among surveys.12

Table 1.

International recommendations for parenteral nutrition in preterm infants

| Tsang et al (2005)9 | ESPEN/ESPGHAN/ESPR guidelines, 20058 | |

|---|---|---|

| Amino acids | ||

| Initiation, g/kg/day | Day of birth | Day of birth |

| Initial dose | 2 | ≥1.5 |

| Target dose | 3.5–4 (ELBW) 3.2–3.8 (VLBW) |

Maximum 4 |

| Glucose | ||

| Initiation, g/kg/day | Day of birth | Day of birth |

| Initial dose | 7 | 5.8–11.5 |

| Target dose | 13–17 (ELBW) 9.7–15 (VLBW) |

– |

| Lipids | ||

| Initiation, g/kg/day | Day of birth (VLBW) Cautious support for ELBW |

No later than 3rd day |

| Initial dose | ≥1 | Linoleic acid >0.25 mg/kg/day |

| Target dose | 3–4 | 3–4 |

| Energy | ||

| Caloric target, g/kg/day | 105–115 (ELBW) 90–100 (VLBW) |

110–120 |

VLBW, very-low-birth-weight infants; ELBW, extremely-low-birth-weight infants; —, no recommendation provided; ESPEN/ESPGHAN/ESPR, European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism/European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition/European Society of Paediatric Research.

The level of adherence to guidelines is often not known and it remains unclear to what extent the recommendations for early parenteral nutrition in NICU patients have been translated into routine clinical care in Europe. Therefore, we performed a clinical practice survey among NICU physicians in four European countries to evaluate compliance to international guidelines for PN in preterm infants and to determine factors that influence compliance to guidelines.

Methods

The survey questionnaire was developed under the lead of AL together with the coauthors. The survey was conducted between October 2009 and April 2010 among NICU physicians in Germany, the UK, France and Italy in order to survey ∼50 units per country. One author from each country provided a list of the largest NICUs using available data and their own knowledge of national and regional units, with at least one senior physician's name per unit. NICUs were selected for the study if they had high acuity/intensive care beds and >5 infants per week requiring PN. The senior physician from each NICU was contacted and asked to complete the survey questionnaire or delegate the task to a colleague devoting ≥20% of their time to patient care and with >3 years of clinical experience in neonatal intensive care. Where a response was not obtained, other physicians from the same unit were approached, if available. The identity of the physicians contacted and requested to complete the survey remained blinded for the analysis and to all authors.

The survey questionnaire was developed in English and translated into German, French and Italian for use in the national language of each country. For the purpose of the survey, PN was defined as intravenous nutrition given through a central or peripheral line and containing fluids and any macronutrients or micronutrients. Respondents were instructed to consider only in-hospital neonatal intensive care patients. D0 was defined as the day of birth, D1 for the subsequent 24 h, and D2 and D3 the following days. The survey comprised sections to characterise the profile of the NICU, and routine clinical practice with respect to PN. The survey assessed the logistical organisation of PN within the hospital, the types of PN available and prescribed, and some of the reasons for use or non-use of standard formulations, as well as the preferred product characteristics and awareness and implementation of local and international clinical practice guidelines. Only the unit profile, the routine clinical practice with respect to PN and awareness and implementation of guidelines were analysed for this report.

The survey was implemented in a web-based format by an independent company (GfK SE Division HealthCare, Nürnberg, Germany). The authors and the sponsor were blinded with regard to the respondents’ identities and with regard to the individual questionnaires. To best describe the macronutrient or energy provision, single choice questions were asked offering six possible answers, five with plausible intakes and one ‘do not know’ response. To assess the extent of agreement with statements related to the awareness and implementation of guidelines, questions were asked using a 7-point bipolar scale, 1 meant ‘do not agree at all’ and 7 meant ‘fully agree’.

Compliance to international guidelines for PN in preterm infants was made mainly by using the European ones since they have been published in a journal widely disseminated8 and since they are also easily and freely accessible through the ESPEN website (http://espen.anavajo.com/espencms/index.php/education/espen-guidelines). NICUs were considered compliant to guidelines if: for amino acids, initiation=day of birth, initiation dose ≥1.5 g/kg/day, target dose=3–4 g/kg/day; for glucose, initiation dose ≥7 g/kg/day, target dose=10–17 g/kg/day; for lipids, initiation ≤day 3 of life, initiation dose ≥1 g/kg/day, target dose=3–4 g/kg/day; energy, target dose=110–120 kcal/kg/day.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were restricted to completed questionnaires with evaluable results. Data were split to cross tabs with respect to various grouping variables. Since infants with a birth weight below 1500 g are those more likely to receive PN, splitting the data using this parameter was considered to better reflect the experience in prescribing PN than using the whole population of newborns admitted in an NICU. Therefore, first-class split variables consisted of tertiles or quartiles, which were computed on the average number of admissions to the NICU per year by birth weight up to 1500 g. The second class of grouping factors comprised categorical variables such as hospital type or country. The goal was to examine the null hypothesis ‘No pairwise differences in proportions across subgroups’. Null hypotheses were tested using χ² tests and rejected at the 5% error level.

Ethics

This study was conducted according to the guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki. Since this study did not involve human subjects/patients or handling of medical records, ethical approval was not required.

Results

Profile of the NICUs surveyed

A total of 199 NICUs were surveyed (45 from the UK, 55 from Germany, 49 from France and 50 from Italy) and their characteristics are presented in table 2. Overall, we surveyed 74% of the units of the four countries: 45/64 (70%) in the UK; 55/78 (71%) in Germany; 49/66 (74%) in France; 50/60 (83%) in Italy). One hundred and sixty-one of the 199 (81%) surveys were included in the analysis as 38 surveys were excluded due to invalid responses. The majority of invalid surveys came from units with a lower number of high acuity care beds (ie, 50% of them had ≤5 high acuity care beds vs 12%; p<0.001). The number of years of practice in neonatology of the physicians who completed the survey questionnaire was more than 10 years for 141 of them (71%), 5–9 years for 40 of them (20%), 3–5 years for 17 of them (8.5%) and 1–3 years for 1 of them (0.5%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of participating NICUs

| Characteristic | Total | Germany | UK | France | Italy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaires received, n | 199 | 55 | 45 | 49 | 50 |

| Questionnaires analysed, n | 161 | 54 | 39 | 49 | 19 |

| Type of hospital, n (%) | |||||

| University/teaching hospital | 106 (66) | 44 (82) | 27 (69) | 31 (63) | 4 (21) |

| Non-university | 55 (34) | 10 (19) | 12 (31) | 18 (37) | 15 (79) |

| Highest acuity beds per unit, n (%) | |||||

| 1–5 | 19 (12) | 2 (4) | 8 (21) | 3 (6) | 6 (32) |

| 6–10 | 73 (45) | 22 (41) | 21 (54) | 23 (47) | 7 (37) |

| 11–15 | 45 (28) | 18 (33) | 5 (13) | 19 (39) | 3 (16) |

| ≥16 | 24 (15) | 12 (22) | 5 (13) | 4 (8) | 3 (16) |

| Intermediate care beds per unit, n (%) | |||||

| 1–5 | 30 (19) | 13 (24) | 5 (13) | 4 (8) | 8 (42) |

| 6–10 | 56 (35) | 16 (30) | 15 (39) | 17 (35) | 8 (42) |

| 11–15 | 33 (21) | 9 (17) | 6 (15) | 15 (31) | 3 (16) |

| ≥16 | 38 (24) | 14 (26) | 13 (33) | 11 (22) | 6 (12) |

| NR | 4 (3) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) |

| VLBW infants per year, median (IQR) | 90 (129–60) | 64 (86–40) | 105 (160–80) | 125 (195–98) | 75 (90–55) |

Percentages do not necessarily sum up to 100% due to rounding.

NICUs, neonatal intensive care units; NR, no response; VLBW, very-low-birth–weight.

Adherence of unit protocol to international guidelines

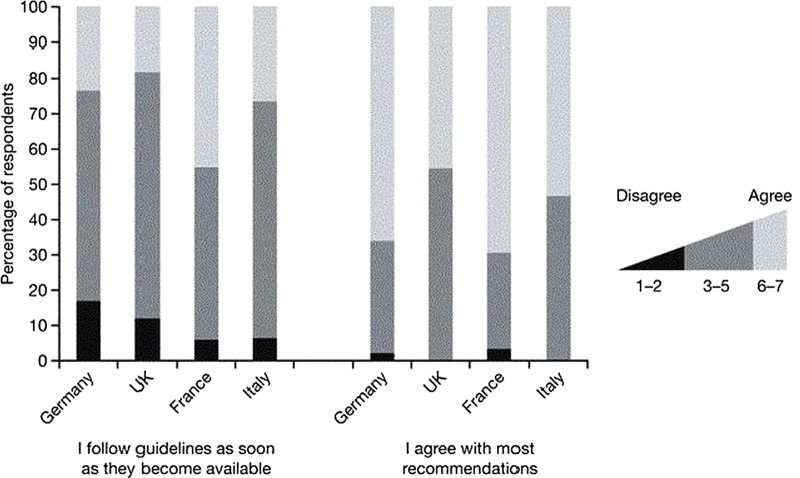

Survey respondents were requested to provide information on the timing and composition of PN as summarised in table 3. The level of adherence of unit protocols to international guidelines was highly variable and varied according to the type of macronutrient (figure 1). With regard to initiation of PN, AAs were often initiated late and lipids and AAs were initiated at a lower dose than recommended (figure 1). With regard to full PN (ie, target dose), most NICUs reported an adequate target dose for AAs, lipids and glucose. In contrast, only half of the units reported a target energy intake compliant with guidelines; ∼20% reported a lower higher target than recommended and a similar percentage a higher target than recommended.

Table 3.

Current practice for parenteral nutrition in NICU patients by country

| Total | Germany | UK | France | Italy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Amino acids | |||||

| Initiation (p=0.005) | |||||

| D0 | 101 (63) | 32 (59) | 21 (54) | 41 (84) | 7 (37) |

| D1 | 51 (32) | 19 (35) | 15 (39) | 8 (16) | 9 (47) |

| D2 or later | 9 (6) | 3 (6) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 3 (16) |

| Initial dose (p=0.001), g/kg/day | |||||

| 0.5 | 44 (27) | 20 (37) | 11 (28) | 5 (10) | 8 (42) |

| 1.0 | 53 (33) | 14 (26) | 9 (23) | 24 (49) | 6 (32) |

| 1.5 | 34 (21) | 5 (9) | 11 (28) | 15 (31) | 3 (16) |

| 2 or higher | 27 (17) | 15 (28) | 5 (13) | 5 (10) | 2 (11) |

| Do not know | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Target dose (p<0.001), g/kg/day | |||||

| 1 or 2 | 11 (7) | 6 (11) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) |

| 3 or 4 | 146 (91) | 48 (89) | 34 (87) | 49 (100.0) | 15 (79) |

| 5 or higher/do not know | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) |

| Glucose | |||||

| Initial dose (p<0.001), g/kg/day | |||||

| 6 | 73 (45) | 27 (50) | 12 (31) | 19 (39) | 15 (79) |

| 7 | 41 (26) | 18 (33) | 3 (8) | 18 (37) | 2 (11) |

| 8 | 28 (17) | 6 (11) | 9 (23) | 12 (25) | 1 (5) |

| 9 or higher | 17 (11) | 3 (6) | 13 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Do not know | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Target dose (p<0.001), g/kg/day | |||||

| 15 | 68 (42) | 22 (41) | 21 (54) | 8 (16) | 17 (90) |

| 16 | 38 (24) | 14 (26) | 5 (13) | 18 (37) | 1 (5) |

| 17 | 12 (8) | 5 (9) | 2 (5) | 5 (10) | 0 (0) |

| 18 or higher | 32 (20) | 10 (19) | 3 (8) | 18 (37) | 1 (5) |

| Do not know | 11 (7) | 3 (6) | 8 (21) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Lipids | |||||

| Initiation (p=0.160) | |||||

| D0 | 32 (20) | 12 (22) | 12 (31) | 3 (6) | 5 (26) |

| D1 | 77 (48) | 24 (44) | 17 (44) | 28 (57) | 8 (42) |

| D2 | 36 (22) | 11 (20) | 9 (23) | 11 (22) | 5 (26) |

| D3 or later | 16 (10) | 7 (13) | 1 (3) | 7 (14) | 1 (5) |

| Do not know | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Initial dose (p<0.001), g/kg/day | |||||

| 0.5 | 98 (61) | 34 (63) | 11 (28) | 36 (74) | 17 (90) |

| 1.0 | 59 (37) | 18 (33) | 27 (70) | 13 (27) | 1 (5) |

| 1.5 or higher | 3 (2) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Do not know | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Target dose (p=0.028), g/kg/day | |||||

| 1 or 2 | 34 (21) | 15 (28) | 3 (8) | 9 (18) | 7 (37) |

| 3 or 4 | 123 (76) | 38 (70) | 33 (85) | 40 (82) | 12 (63) |

| 5 or higher/do not know | 4 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Caloric target (p<0.001), kcal/kg/day | |||||

| 90 or 100 | 29 (18) | 3 (6) | 15 (39) | 3 (6) | 8 (42) |

| 110 | 28 (17) | 8 (15) | 6 (15) | 11 (22) | 3 (16) |

| 120 | 65 (40) | 25 (46) | 10 (26) | 26 (53) | 4 (21) |

| 130 or more | 35 (22) | 18 (33) | 4 (10) | 9 (18) | 4 (21) |

| Do not know | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Maximal caloric intake prescribed (p<0.001), kcal/kg/day | |||||

| 110 | 13 (8) | 1 (2) | 7 (18) | 3 (6) | 2 (11) |

| 120 | 36 (22) | 9 (17) | 12 (31) | 9 (18) | 6 (32) |

| 130 | 32 (20) | 10 (19) | 4 (10) | 12 (25) | 6 (32) |

| 140 | 37 (23) | 16 (30) | 2 (5) | 18 (37) | 1 (5) |

| 150 or more | 34 (21) | 18 (33) | 6 (15) | 6 (12) | 4 (21) |

| Do not know | 9 (6) | 0 (0) | 8 (21) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

Percentages do not necessarily sum up to 100% due to rounding.

Recommended intakes as defined in the Methods section are highlighted in bold.

D0, day 0; D1, day 1; D2, day 2.

Figure 1.

Percentage of NICUs (n=161) in Germany, France, Italy and the UK compliant to guidelines for parenteral nutrition in preterm infants. NICUs were considered compliant to guidelines if: for amino acids, initiation=day of birth, initiation dose ≥1.5 g/kg/day, target dose=3–4 g/kg/day; for glucose, initiation dose ≥7 g/kg/day, target dose=10–17 g/kg/day; for lipids, initiation ≤day 3 of life, initiation dose ≥1 g/kg/day, target dose=3–4 g/kg/day; energy, target dose=110–120 kcal/kg/day.

Factors that influence adherence to guidelines

Country, hospital type and size of unit

There was a significant effect of countries on PN practices (table 3). The patterns observed were the following: with regard to early PN, AAs were started sooner and at a higher dose in France than in the other countries. A similar trend was seen for lipids in the UK where the starting dose of glucose was also higher than in the other countries. With regard to full PN (ie, target dose), the AA target dose was more likely within the recommendations in France than in other countries, whereas the glucose target dose was more likely within the recommendations in the UK and in Italy. The distribution for caloric target was wide; the units in France and Germany were more likely prescribing higher energy intake than recommended, whereas lower energy intake was more likely seen in the UK and Italy.

When the PN results were stratified by hospital type, no differences were observed in the initiation, starting or target dose of AAs (data not shown). University or teaching hospitals reported higher starting doses of glucose than other types of hospital (40% vs 56% at 6 g/kg/day and 32% vs 13% at 7 g/kg/day; p=0.022), but there was no significant difference in the target dose between the two types of institutions. University or teaching hospitals also reported initiation of lipid feeding earlier than other institutions (initiation on D3 or later 5% vs 20%; p=0.015), but with no significant difference in the starting or target dose. The caloric targets between the two types of hospitals were similar, but the normal maximal caloric intakes prescribed were significantly different (p=0.008).

When the data were stratified by the number of admissions, the only category in which a significant difference was apparent was the day on which lipid feeding was initiated. Units with lower admission rates were more likely to report initiation on D3 or later (p=0.011) (data not shown).

Awareness of nutritional guidelines

Eighty per cent of physicians across all countries reported an awareness of nutritional guidelines, but less than 50% gave a source or specification (table 4). There were intercountry differences for physicians reporting an awareness of clinical practice guidelines for neonatal or paediatric PN (table 4). There was no significant association between being aware of guidelines for use of neonatal/paediatric PN and being compliant with international guidelines, but there was a trend for an association between being aware of guidelines and being compliant with the lipid target dose (p=0.054) and with the initiation of AAs (p=0.070).

Table 4.

Guideline awareness by country

| Question | TOTAL | Germany | UK | France | Italy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Are you aware of the guidelines for use of neonatal/pediatric PN? | |||||

| Yes | 128 (80) | 47 (87) | 33 (85) | 33 (67) | 15 (79) |

| No | 33 (21) | 7 (13) | 6 (15) | 16 (33) | 4 (21) |

| Of which guidelines are you aware?* | |||||

| International8 21 | 33 (26) | 10 (21) | 9 (27) | 10 (30) | 4 (27) |

| National | 24 (19) | 16 (34) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 6 (40) |

| In-house guidelines | 8 (6) | 4 (9) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) |

| None specifically named/other | 66 (52) | 19 (40) | 17 (52) | 24 (73) | 6 (40) |

PN,parenteral nutrition.

*More than one answer per questionnaire possible.

Percentages do not necessarily sum up to 100% due to rounding.

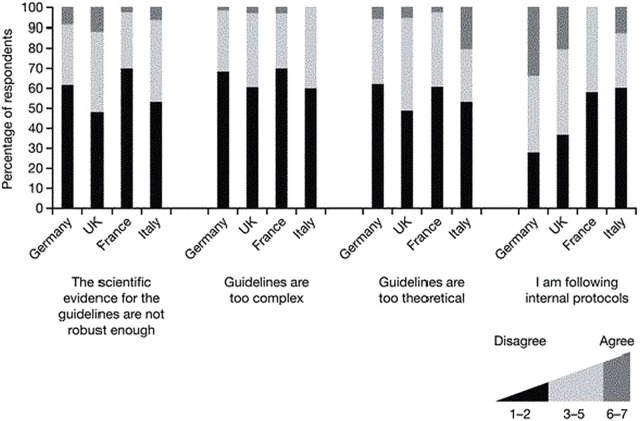

Respondents indicated that they agreed with most of the recommendations, with 66% and 70% of physicians from Germany and France and 46% and 53% in UK and Italy in strong agreement (figure 2). Overall, the physicians agreed less strongly with the statement ‘I obtain a copy, read and follow guidelines for parenteral nutrition in paediatric patients as soon as they become available’ (figure 2). When asked whether the lack of robust evidence on which the guidelines are based presented a barrier to implementation, 3% and 7% of the physicians from France and Italy agreed, in comparison to 9% and 12% of the respondents from Germany and the UK (figure 3). About 60–70% of the physicians did not find the current guidelines too complex and those from the UK and Italy more often found the guidelines to be too theoretical to be used in clinical practice than respondents from Germany or France. Respondents from Germany were more likely to report relying on internal clinical practice protocols (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Use of international clinical practice recommendations to guide neonatal parenteral nutrition by country.

Figure 3.

Justification for non-implementation of international clinical practice guidelines by country.

Discussion

This study represents the first survey of neonatal PN clinical practice behaviour undertaken at the European level. This type of survey emphasises how current practices differ from recommended guidelines and encourage clinicians to be aware of the potential for improvement. Since the objective of the study was to compare the data with international guidelines, we did not report and/or use local guidelines, if any, and for consistency, we mainly used for comparison the European guidelines, which are widely available through a publication widely referenced8 and a website.

Despite demonstrating an apparent improvement in PN practices, the results presented here show that 37% of neonatal units in the four European countries surveyed initiate AA feeding on D1 or later and not on D0 as recommended.8 Moreover, 60% of the European respondents administer an initial dose of less than the required 1.5 g/kg/day to prevent a negative balance.8 The apparently higher compliance with the guideline recommendations to initiate AA infusion on D0 and a target dose of 3–4 g/kg/day in France may be attributable to a combination of commercially available binary standard solutions and/or awareness of a national survey on this topic and be widely disseminated at the country level.13

Our study shows that while 90% of the NICUs surveyed provide early lipids, 21% of them provide a maximum dose lower than recommended. This is similar to other surveys, suggesting that physicians do not comply easily with the guideline defining the optimal dose for parenteral lipids. Previous surveys have shown that the timing and dose of parenteral lipids vary between surveys to a scale that is larger than that for AAs.12 It was also found that there was a lack of consensus between surveys on the contraindications for lipids and/or indication for stopping lipids. This may reflect the lack of scientific data and absence of clear guidance on this topic.

Awareness of some guidelines was reported by the majority of physicians completing the survey, although 21% claimed not to be aware of any guidelines. This may be of relevance when the 40% of respondents who do not provide AAs on the day of birth are considered, highlighting a potential deficit in implementation of the guidelines. Limited access to standard solutions and specific country regulations on preparation may also be possible alternative explanations why guidelines have not been translated into clinical practice.

University/teaching hospitals provided a higher starting dose of glucose and initiated lipid and AA infusion earlier compared to other institutions. Similarly, late initiation of lipid infusion (D3 or later) was less common in NICUs with the highest number of admissions per year. While these results may suggest better adherence to treatment guidelines at hospitals with a high number of admissions, the existing data are unclear as to whether high numbers of admissions are also associated with lower rates of mortality or morbidity.14 15

The methodological limitations of using surveys for the assessment of nutritional protocols have been previously discussed in detail,13 and it should be reiterated that while these surveys reflect the intention to treat of the personnel from the NICU who respond to the survey, they may not reflect the actual clinical practice within the unit. Nevertheless, the intention to treat reflects one of the first steps of the dissemination of guidelines and thus provides insight on compliance to guidelines. The number of countries participating in our survey was limited to four for practical reasons, and therefore the results obtained do not permit conclusions that apply to other European countries. The number of surveys received represents a substantial proportion of NICUs in each of the four countries; however, the number of invalid surveys indicates that there may have been some confusion with respect to terminology or intent. Interestingly, the invalid responses were mainly seen in the smaller units, which are less likely to prescribe PN.

Finally, our results not only allow a comparison of current practices among countries but also a historical comparison with similar surveys published earlier.12 When compared to studies performed in the USA16 or individual European countries,17–20 our study shows that PN in preterm neonates is provided earlier and in higher volumes than in the past, reflecting the changing clinical practice in response to increased knowledge about parenteral feeding in neonates, even if the practices are still not perfectly in line with guidelines.

In conclusion, most respondents indicate that their clinical practice was based on common guidelines. However, the initiation of PN in the four countries surveyed is frequently not compliant with the current recommendations, with the main differences observed during the first days of life. Our study shows that there is an urgent need to improve the dissemination of guidelines and to facilitate translation of knowledge into clinical practice. Given the need for continuous monitoring, it would be of value for scientific societies (particularly those that publish guidelines) to develop web-based standard reporting systems that determine the actual compliance of in-house protocols with guidelines. In the case of nutrition for preterm infants, a limited number of questions on access to PN and the dose of nutrients given would be sufficient to provide insight on the implementation of guidelines at the local level.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Istvan Szabo, Ines Pereira da Silva Lopes and Michael Imeokparia from Baxter Healthcare (Glattpark, Switzerland) for their insightful contribution to the project. Editorial assistance was provided by Physicians World Europe GmbH (Mannheim, Germany), sponsored by Baxter Healthcare. The authors thank the Association pour la Recherche et la Formation En Neonatologie (ARFEN) for providing technical assistance. Special thanks go to all the physicians who have completed the questionnaire for their contribution.

Footnotes

Contributors: The manuscript was drafted by AL. He also participated in the review, revision and approval of the manuscript and had access to all the primary data. VPC participated in the review, revision and approval of the manuscript and had access to all the primary data. NDE participated in the review, revision and approval of the manuscript and had access to all the primary data. WM participated in the review, revision and approval of the manuscript and had access to all the primary data.

Funding: This study was sponsored by Baxter Healthcare (Glattpark, Switzerland), which provided support for the development and implementation of the survey, face-to-face meetings and writing of manuscript. All authors have received an unrestricted institutional grant from Baxter Healthcare for coordinating the study in their own country.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: See materials and methods section: ‘The survey assessed the logistical organisation of PN within the hospital, the types of PN available and prescribed, and some of the reasons for use or non-use of standard formulations, preferred product characteristics and awareness and implementation of local and international clinical practice guidelines. Only the unit profile, clinical practice parameters and awareness and implementation of guidelines were analysed for this report. ’ The data are available to the authors and the sponsor.

References

- 1.Isaacs EB, Gadian DG, Sabatini S, et al. The effect of early human diet on caudate volumes and IQ. Pediatr Res 2008;63:308–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lapillonne A, Griffin IJ. Feeding preterm infants today for later metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes. J Pediatr 2013;162(Suppl 3):S7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dit Trolli SE, Kermorvant-Duchemin E, Huon C, et al. Early lipid supply and neurological development at one year in very low birth weight (VLBW) preterm infants. Early Hum Dev 2012;88(Suppl 1):S25–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stephens BE, Walden RV, Gargus RA, et al. First-week protein and energy intakes are associated with 18-month developmental outcomes in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2009;123:1337–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin CR, Brown YF, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Nutritional practices and growth velocity in the first month of life in extremely premature infants. Pediatrics 2009;124:649–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen IE, Richardson DK, Schmid CH, et al. Intersite differences in weight growth velocity of extremely premature infants. Pediatrics 2002;110:1125–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corpeleijn WE, Vermeulen MJ, Van den Akker CH, et al. Feeding very-low-birth-weight infants: our aspirations versus the reality in practice. Ann Nutr Metab 2011;58(Suppl 1):20–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koletzko B, Goulet O, Hunt J, et al. 1. Guidelines on Paediatric Parenteral Nutrition of the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN), Supported by the European Society of Paediatric Research (ESPR). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2005;41(Suppl 2):S1–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsang R, Uauy R, Koletzko B, et al. Nutritional needs of the preterm infant: scientific basis and practical guidelines. Cincinnati: Digital Educational Publishing Inc, OH, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackwell MT, Eichenwald EC, McAlmon K, et al. Interneonatal intensive care unit variation in growth rates and feeding practices in healthy moderately premature infants. J Perinatol 2005;25:478–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark RH, Thomas P, Peabody J. Extrauterine growth restriction remains a serious problem in prematurely born neonates. Pediatrics 2003;111(5 Pt 1):986–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lapillonne A, Kermorvant-Duchemin E. Parenteral nutrition for NICU patients—a systematic review of current practice surveys. J Nutr. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.176982. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lapillonne A, Fellous L, Mokthari M, et al. Parenteral nutrition objectives for very low birth weight infants: results of a national survey. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;48:618–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phibbs CS, Baker LC, Caughey AB, et al. Level and volume of neonatal intensive care and mortality in very-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2165–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horbar JD, Badger GJ, Lewit EM, et al. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with variation in 28-day mortality rates for very low birth weight infants. Vermont Oxford Network. Pediatrics 1997;99:149–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hans DM, Pylipow M, Long JD, et al. Nutritional practices in the neonatal intensive care unit: analysis of a 2006 neonatal nutrition survey. Pediatrics 2009;123:51–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grover A, Khashu M, Mukherjee A, et al. Iatrogenic malnutrition in neonatal intensive care units: urgent need to modify practice. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2008;32:140–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lapillonne A, Fellous L, Kermorvant-Duchemin E. Use of parenteral lipid emulsions in French neonatal ICUs. Nutr Clin Pract 2011;26:672–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed M, Irwin S, Tuthill DP. Education and evidence are needed to improve neonatal parenteral nutrition practice. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2004;28:176–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleming P, Chong A, Woolhead E, et al. A national survey of current practice in the management of very low and extremely low birth weight infants: is there a role for national guidelines? Ir Med J 2008;101:310–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powers RW, Catov JM, Bodnar LM, et al. Evidence of endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia and risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. Reprod Sci 2008;15:374–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.