Abstract

Introduction

Relatively few studies have evaluated the impacts of heterogeneous spatiotemporal pollutant distributions on health risk estimates in time-series analyses that use data from a central monitor to assign exposures. We present a method for examining the impacts of exposure measurement error relating to spatiotemporal variability in ambient air pollutant concentrations on air pollution health risk estimates in a daily time-series analysis of emergency department visits in Atlanta, Georgia.

Methods

We used Poisson generalized linear models to estimate associations between current day pollutant concentrations and circulatory emergency department visits for the 1998–2004 period. Data from monitoring sites located in different geographical regions of the study area and at different distances from several urban geographic subpopulations served as alternative measures of exposure.

Results

We observed associations for spatially heterogeneous pollutants (CO and NO2) using data from several different urban monitoring sites. These associations were not observed when using data from the most rural site, located 38 miles from the city center. In contrast, associations for spatially homogeneous pollutants (O3 and PM2.5) were similar regardless of monitoring site location.

Conclusions

We found that monitoring site location and the distance of a monitoring site to a population of interest did not meaningfully impact estimated associations for any pollutant when using data from urban sites located within 20 miles from the population center under study. However, for CO and NO2, these factors were important when using data from rural sites, located greater than 30 miles from the population center, likely due to exposure measurement error. Overall, our findings lend support to the use of pollutant data from urban central sites to assess population exposures within geographically dispersed study populations in Atlanta and similar cities.

Keywords: air pollution, cardiovascular disease, emergency department visits, exposure assessment, measurement error, time-series

Introduction

A common method for assigning exposure in population-based epidemiologic studies of ambient air pollution is to use measurements obtained from central site ambient monitors (Wilson et al., 2005). However, uncertainties exist as to how well these concentrations represent true personal exposures to different pollutants, under different study designs and in different geographic settings, and how resulting exposure measurement error may impact health risk estimates in epidemiologic analyses.

There are several potential sources of exposure measurement error when using observed ambient measurements to estimate personal exposures, including: 1) instrument error; 2) error resulting from the placement of a monitor (reflected by the representativeness of the monitoring site and spatial variability of the pollutant measured); and, 3) differences between the ambient monitored concentration and average personal exposure (NRC, 1998). Simulation studies suggest that the difference between true and measured ambient pollutant levels has likely small impacts on time-series health risk estimates (Sheppard et al., 2005; Zeger et al., 2000). However, these studies either assumed spatial homogeneity in the air pollutant or only considered a pollutant (PM2.5) with little spatiotemporal variation.

Total PM2.5 and secondary pollutants, such as ozone (O3), are often relatively homogeneous over space, in that their concentration levels as well as the temporal fluctuations in their concentrations are relatively consistent over metropolitan areas. However, other pollutants, including those emitted by motor vehicles, such as carbon monoxide (CO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), are likely to display spatiotemporal heterogeneity, such that their concentrations levels and/or the temporal fluctuations in their concentrations vary over metropolitan areas (also referred to as spatiotemporal variability). Spatially heterogeneous pollutants include both primary pollutants (e.g., CO and nitric oxide [NO]) and those formed by relatively rapid conversion of a primary pollutant (e.g., NO2).

The potential implications of heterogeneous spatiotemporal pollutant distributions on epidemiologic findings are frequently discussed in the literature (Ito et al., 2005; Pinto et al., 2004; Wilson et al., 2005; Wilson et al., 2006), but relatively few studies have directly evaluated the impacts of such pollutant distributions on health risk estimates in time-series analyses that use data from a central monitor to assign exposures. Two recent publications have attempted to do so for particle exposures by comparing health effect estimates among models predicting outcome events for several geographic subpopulations located at different distances from a central monitoring site (Wilson et al., 2007), and among models using local (i.e., closest) site monitoring data as a comparison to central monitoring data to assess exposures for geographic subpopulations (Chen et al., 2007).

In a daily time-series study of ambient particles and cardiovascular mortality in Phoenix, Wilson et al. (2007) found that effect estimates for PM2.5, but not for PM10-2.5, were lower for models predicting mortality in geographic subpopulations residing further from a central monitoring site compared to analyses of the population residing closest to the site. Because socioeconomic status (SES) of the three subpopulations increased with increasing distance from the central site, the authors suggested two factors that influenced the observed pattern of effects: 1) exposure error (poorer agreement between local population average exposure and the centrally-monitored PM2.5 concentrations with increasing distance from the central site); and, 2) effect modification by SES (lesser sensitivity to the effects of PM2.5 with increasing SES). It has been noted that SES may be a surrogate of various underlying characteristics that can modify the impacts of ambient air pollution on a population, including susceptibility (e.g., due to poor health in general), health-related behaviors (e.g., smoking, nutrition), as well as disease diagnosis and treatment (e.g., less access to healthcare) (Bell et al., 2005). Individuals with low SES may also have higher personal exposures to ambient pollution (e.g., by living closer to roads or other specific pollution point sources or having lower air conditioning usage) compared to those of higher SES.

We previously presented the results of a geographic sub-analysis of cardiorespiratory emergency department (ED) visits and ambient particle and gaseous pollutants (Sarnat et al., 2006), conducted as part of the Study of Particles and Health in Atlanta (SOPHIA) (Tolbert et al., 2000). Observed associations between ambient pollutants and ED visits, particularly for circulatory diseases, were stronger when we limited the geographic domain of the study population analyzed to residential areas closer to the central monitoring sites compared to analyzing the full geographic domain of the study (Sarnat et al., 2006). These results were expected under the assumption that data from an ambient monitoring site provide better markers of exposure for populations residing in close proximity to the site compared to those residing further away. However, in this analysis, associations were stronger for both spatially heterogeneous pollutants (e.g., CO and NO2) and for pollutants with fairly homogeneous spatial distributions (e.g., PM2.5 and sulfate), suggesting that decreased exposure measurement error in the geographic sub-analyses as compared to the full analysis may not have been the only explanation. It is possible, for example, that population characteristics that confer sensitivity to air pollution, such as sociodemographic factors, may have also impacted our findings.

These analyses demonstrate the difficulty of disaggregating the impacts of exposure measurement error from the impacts of population characteristics in geographic subpopulation comparison studies. For example, if we observe stronger associations between air pollutant concentrations measured at a central ambient monitoring site and health outcomes in a population (A) residing close to the monitor compared to a population (B) residing further from that monitor, the pattern could be due in part to 1) reduced exposure measurement error for population A and/or 2) greater susceptibility of population A to the pollutant of interest. Here, we present a method for examining the impacts of exposure measurement error relating to spatiotemporal variability in ambient air pollutant concentrations on air pollution health risk estimates in our daily time-series analyses while controlling for the potential modifying effects of population characteristics. Rather than using data from one central site and comparing health effect associations across different geographic subpopulations, our method examines single geographic subpopulations and compares health effect associations using pollutant data from different monitoring sites as alternative measures of exposure. Since we compare risk estimates within the same population over the same time period, any observed differences in risk when using different measures of exposure should not be attributed to differences in population susceptibility. For example, if we observe stronger associations for population A using ambient data from a monitor located in close proximity compared to a monitor located further away, the difference in associations may be reasonably explained by differences in exposure measurement error between the two measures of exposure.

Our method relies on availability of daily air monitoring data from multiple monitoring sites over a sufficiently long time period, as well as a population and health outcome supplying sufficient cases for geographic subpopulation analyses. In this analysis, we examined data from our Atlanta ED study over the 1998–2004 time period, for which daily CO, NO2, O3 and PM2.5 concentrations were available from several monitoring sites located throughout the study area.

Methods

Ambient Air Quality Data

We obtained daily ambient concentration data for 1-hour maximum CO, 1-hour maximum NO2, 8-hour maximum O3 and 24-hour average PM2.5 from all monitoring stations in the 20-county Atlanta study area that operated and collected daily measurements for one or more of these pollutants during all or a portion of the study period, August 1 1998 through December 31 2004. Data for all pollutants were available year-round, with the exception of O3, for which data were generally only available between April and October. We also obtained daily meteorologic data, including average temperature and dew point temperature, for Hartsfield-Atlanta International Airport from the National Climatic Data Center.

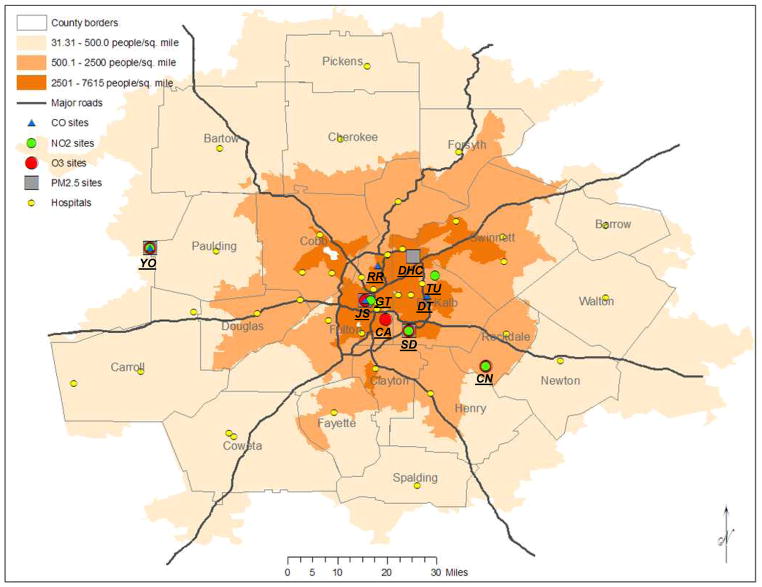

The air monitoring stations, their characteristics and their locations in the study area are described in Table 1 and Figure 1. The monitoring stations included those in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Air Quality System (U.S. EPA, 2007), the SouthEastern Aerosol Research and Characterization Study network (ARA, 2007) and the Assessment of the Spatial Composition in Atlanta network (Butler et al., 2003). In total, 10 sites provided data for this analysis, with four to five different sites per pollutant. Based on population density data and proximity to the Atlanta city center (e.g., within or close to the I-285 perimeter highway that circles the more central parts of the city), we considered the following sites as urban: Jefferson St. (JS), Georgia Tech (GT), Confederate Ave. (CA), Roswell Rd (RR), South Dekalb (SD), Dekalb Tech (DT), Doraville Health Center (DHC), and Tucker (TU); and the following sites as rural: Conyers (CN), and Yorkville (YO) (Figure 1). JS is the site of the Aerosol Research Inhalation Epidemiology Study (ARIES) (Hansen et al., 2006) and the EPA Atlanta Supersites project (Solomon et al., 2003), and has been considered the primary site for particle pollutants in previous publications by this research group (Metzger et al., 2004; Peel et al., 2005; Sarnat et al., 2008; Tolbert et al., 2007). In the current analysis, we used JS as the default central site for CO, O3 and PM2.5 and GT as the central site for NO2, located approximately one mile from JS. YO was the most rural site, at a distance of 38 miles from JS.

Table 1.

Ambient monitoring sites, including pollutants measured and site characteristics.

| Site Name (Abbreviation) | Networka | AQS Site ID | Distance from JS (miles) | Pollutantb | AQS Site Characterizationc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| CO | NO2 | O3 | PM2.5 | Location Setting | Land Use | Monitoring Objective | ||||

| Jefferson St (JS) | SEARCH | n/a | 0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓d | Urban and center city | Industrial | n/a | |

| Georgia Tech (GT) | AQS | 131210048 | 0.92 | ✓ | Urban and center city | Commercial | Highest concentration | |||

| Confederate Ave (CA) | AQS | 131210055 | 5.2 | ✓ | Suburban | Commercial | Population exposure | |||

| Roswell Rd (RR) | AQS | 131210099 | 7.2 | ✓ | Suburban | Commercial | Highest concentration | |||

| South Dekalb (SD) | AQS, ASACA | 130890002 | 9.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓d | Suburban | Residential | Population exposure (NO2,

PM2.5) Highest concentration (O3) |

|

| Dekalb Tech (DT) | AQS | 130891002 | 10.4 | ✓ | Suburban | Residential | Population exposure | |||

| Doraville Health Center (DHC) | AQS | 130892001 | 11.6 | ✓ | Suburban | Commercial | Population exposure | |||

| Tucker (TU) | AQS | 130893001 | 12.7 | ✓ | Rural | Residential | Unknown | |||

| Conyers (CN) | AQS | 132470001 | 24.1 | ✓ | ✓ | Rural | Agricultural | Population exposure (NO2,

O3) Max concentration (O3) |

||

| Yorkville (YO) | SEARCH, AQS | 132230003 | 37.6 | ✓ | ✓d | ✓ | ✓d | Rural | Agricultural | General background (CO, NO2,

O3) Upwind background (PM2.5) |

SEARCH=SouthEastern Aerosol Research and Characterization study; AQS=U.S. EPA Air Quality System; ASACA=Assessment of the Spatial Composition in Atlanta

Check marks in pollutant columns indicate which sites measured each pollutant

All site characterization entries were obtained from the AQS data mart, with the exception of those for Jefferson St.

When data from multiple instruments were available at the same site, primary instruments were selected and any missing values were modeled using data from the other instruments, as follows (FRM – federal reference method, PCM – particle composition monitor, TEOM – tapered element oscillating microbalance):

- at JS, PM2.5 SEARCH FRM data were filled in with regression-adjusted SEARCH PCM and TEOM data

- at SD, PM2.5 AQS FRM data were filled in with regression-adjusted ASACA TEOM data

- at YO, PM2.5 SEARCH FRM data were filled in with regression-adjusted SEARCH TEOM data

- at YO, NO2 AQS data were filled in with regression-adjusted SEARCH data

Figure 1.

20-county Atlanta study area with ZIP code level population density,a location of air pollutant monitoring sites,b and acute-care hospitals.

a Population density (# people/square mile) for 2001

b Air monitoring sites include Jefferson St (JS), Georgia Tech (GT), Confederate Ave (CA), Roswell Rd (RR), South Dekalb (SD), Dekalb Tech (DT), Doraville Health Center (DHC), Tucker (TU), Conyers (CN), and Yorkville (YO)

In order to compare descriptive statistics and epidemiologic model results using data from different monitoring sites, data were matched across sites for each pollutant. For example, if CO measurements from one monitor were missing for a particular day, the CO measurements from the other monitors were set to missing for the same day. This matching process resulted in slightly different time periods examined for each pollutant: 08/01/1998–06/30/2003 for CO, 08/01/1998–12/31/2004 for NO2, 08/01/1998–12/31/2004 for O3 (warm season only), and 03/01/1999–12/31/2004 for PM2.5.

Emergency Department Data

We obtained individual-level data on ED visits for the 20-county (7964 sq. mile) Atlanta population through computerized billing records submitted by 41 of 42 acute-care hospitals (Figure 1). For each patient visit, hospitals provided data on the date of admission, the primary International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision (ICD-9) diagnostic code, patient date of birth, gender, race, and 5-digit residential ZIP code. We defined our outcome of interest, circulatory disease, using primary ICD-9 diagnosis codes 390–459. We excluded repeat visits by patients visiting the same hospital within a single day.

In the overall analytic database, we included ED visits for patients living within any one of the 225 ZIP codes located wholly or partially in the 20-county Atlanta study area. We also created variables to delineate ED visits for specific geographic subpopulations living within five miles of each air monitoring site, identified using the distance between air monitoring sites and patient residential ZIP code centroids. The monitoring site around which each subpopulation was defined was considered to be “local”, or closest, to that population. The five-mile radius was chosen based on the smallest distance from monitoring sites that allowed for sufficient daily ED visit counts for circulatory disease in epidemiologic analyses. Analyses of the geographic subpopulations were limited to those around urban monitoring sites due to lack of population within five miles of rural sites. 0–6% of ZIP codes for CO, NO2 and PM2.5 epidemiologic analyses, and 34% of ZIP codes for O3 analyses, were counted in more than one geographic subpopulation.

Census Data

We obtained Census 2000 data to describe the socioeconomic characteristics of the geographic subpopulations. Using the 5-digit ZIP code tabulation area format, these data were linked to the hospital records by residential ZIP code of each patient. Based on previous research (Krieger et al., 2003), we used the percentage of persons with income below the federally-defined poverty line (% below poverty, [%BP]) as our primary indicator of SES (Census variable P87) (U.S. CB, 2002). We also examined other measures of deprivation (% public assistance, [%PA]), as well as educational attainment (% high school graduation [%HS]) and income (median population housing income) as alternative metrics of SES.

Analyses

We examined the relationships between ED visits for circulatory disease and daily measures of air pollutants using Poisson generalized linear models. As in our previous analyses of these data (Metzger et al., 2004; Peel et al., 2005; Sarnat et al., 2008; Tolbert et al., 2007), the model had the following form:

where Yt was the count of circulatory ED visits on day t in the population of interest (i.e., entire population or specific geographic subpopulation) and pollutantt was the corresponding ambient concentration on day t for the pollutant of interest from the monitoring site of interest. We used lag 0 as the exposure measure based on the literature (Ballester et al., 2006; Wellenius et al., 2006) as well as our data (Metzger et al., 2004), which suggest acute circulatory responses with air pollution. Moreover, the use of a single-day lag as opposed to a multi-day moving average allowed for minimization of missingness upon matching the pollutant data across monitoring sites. Models included indicator variables for day of week (DOW) and holidays (holiday), as well as hospital indicator variables (hospital) to account for the entry and exit of hospitals during the study period. Long-term and seasonal trends in case presentation rates (time) were controlled with parametric cubic splines, g(γ1,…,γN; x), with monthly knots. Due to missing wintertime O3 data, O3 models used separate time splines for each year. Finally, cubic splines were also used to control 3-day moving average (average of lags 0, 1, and 2 days) temperature (temp) and dew point temperature (dewpoint), with knots placed at the 25th and 75th percentiles. With this approach, the first and second derivatives of g(x) are continuous so that time trends and meteorology are modeled as smooth functions. Variance estimates were scaled to account for Poisson overdispersion.

For the entire population, and for each geographic subpopulation, our analytical approach focused on comparing results among models incorporating pollution data from monitoring sites located in different geographical regions of the study area (e.g., urban vs. rural sites) and with different distances from the geographic subpopulation of interest (e.g., local vs. other sites). This approach allowed us to assess the impact of monitoring site location and the distance between monitoring sites and subpopulations on the estimated associations. Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for interquartile range (IQR) increases in the site-specific pollutant data used. IQRs were used for comparing the results of associations based on pollutant data from different monitoring sites, which varied in their range of concentration.

In addition to examining the results for each geographic subpopulation individually, we calculated overall measures of association (using weighted averages) in order to summarize these results for each pollutant. Specifically, the weighted averages were used to compare the impacts of using local urban versus other urban monitoring data on the geographic subpopulation associations, which were difficult to discern from the individual results. For a given set of geographic subpopulations, we compared the weighted averages of relative risk estimates obtained using only local monitoring data with estimates obtained using data from a central urban monitor. The weighted averages were computed on the log scale using the inverse of the variance of the estimates as the weights. To accommodate weighted averages that pooled estimates using data from different monitoring sites, the weighted average relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using common increments (i.e., 1 ppm for CO, 20 ppb for NO2, 25 ppb for O3, and 10 μg/m3 for PM2.5) that approximated urban IQRs.

Epidemiologic analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, V9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and mapping was conducted using ArcGIS ArcMAP V9.2 (ESRI Inc., Redlands, CA).

Results

Air Quality Data

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations (Tables 2 and 3) for each pollutant and site, respectively, show that CO and NO2 levels were spatially heterogeneous across the city, with respect to both their mean levels as well as site-to-site temporal correlations, while O3 and PM2.5 were more spatially homogeneous, as found in previous analyses using these data (Wade et al., 2006). For example, urban-rural differences in mean concentrations were distinct for CO and NO2 (e.g., rural concentrations were a fourth or less of urban concentrations), whereas concentrations were more similar across sites for O3 and PM2.5. In addition, Pearson correlations were moderate (r = 0.61–0.80) among urban sites for CO and NO2, and weak (r = 0.09–0.37) between urban sites and the most rural site, YO. In comparison, correlations for O3 and PM2.5 were high (r = 0.79–0.98) among all sites. The observed patterns of correlations were consistent when analyses were stratified by warm and cool seasons.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for air pollution data.

| Percentiles | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Pollutant | Na | Siteb | Mean | SD | Min | 25th | 50th | 75th | Max | IQRc |

| 1-hr max CO (ppm) | 1374 | JS | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.20 | 0.52 | 0.87 | 1.7 | 7.7 | 1.1 |

| RR | 1.7 | 0.82 | 0.20 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 5.1 | 1.0 | ||

| DT | 1.4 | 0.91 | 0.10 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 7.7 | 1.1 | ||

| YO | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 1.0 | 0.12 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| 1-hr max NO2 (ppb) | 1834 | GT | 40.6 | 18.0 | 1.0 | 27.0 | 38.4 | 51.0 | 172.0 | 24.0 |

| SD | 34.4 | 15.3 | 1.0 | 23.0 | 33.0 | 44.0 | 139.0 | 21.0 | ||

| TU | 32.7 | 13.8 | 3.0 | 23.0 | 32.0 | 41.0 | 100.0 | 18.0 | ||

| CN | 14.5 | 9.9 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 13.0 | 19.0 | 242.0 | 11.0 | ||

| YO | 10.9 | 9.3 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 14.0 | 70.0 | 9.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| 8-hr max O3 (ppb) | 1281 | JS | 52.8 | 21.6 | 2.3 | 37.5 | 50.3 | 67.3 | 130.8 | 29.8 |

| CA | 53.3 | 22.1 | 2.9 | 37.9 | 51.0 | 67.3 | 139.0 | 29.4 | ||

| SD | 49.4 | 20.7 | 2.0 | 34.9 | 48.0 | 62.6 | 135.3 | 27.8 | ||

| CN | 51.9 | 20.0 | 5.4 | 37.5 | 49.8 | 63.3 | 129.3 | 25.8 | ||

| YO | 57.4 | 18.7 | 9.1 | 43.6 | 55.5 | 70.4 | 133.1 | 26.7 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| 24-hr avg. PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 1641 | JS | 16.5 | 8.1 | 1.1 | 10.6 | 15.0 | 20.9 | 65.8 | 10.3 |

| SD | 16.6 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 11.0 | 15.3 | 20.6 | 73.6 | 9.6 | ||

| DHC | 17.1 | 8.5 | 3.0 | 11.2 | 15.5 | 21.0 | 80.0 | 9.8 | ||

| YO | 13.6 | 7.4 | 1.9 | 8.3 | 11.8 | 17.3 | 65.6 | 9.0 | ||

Air pollution data were matched across sites for each pollutant. For example, if CO measurements from one monitor were missing for a particular day, the CO measurements from the other monitors were set to missing for the same day. Therefore, time periods of analysis differed by pollutant: CO=08/01/1998–06/30/2003, NO2=08/01/1998–12/31/2004, O3=08/01/1998–12/31/2004, non-winter; PM2.5=03/01/1999–12/31/2004

Air monitoring sites include Jefferson St (JS), Georgia Tech (GT), Confederate Ave (CA), Roswell Rd (RR), South Dekalb (SD), Dekalb Tech (DT), Doraville Health Center (DHC), Tucker (TU), Conyers (CN), and Yorkville (YO)

IQR = interquartile range

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients for matched air pollutant data (distance in miles between monitoring sites in parentheses). Shaded cells indicate within pollutant (between site) correlations.

| Pollutant | Sitea | CO | NO2 | O3 | PM2.5 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JS | RR | DT | YO | GT | SD | TU | CN | YO | JS | CA | SD | CN | YO | JS | SD | DHC | ||

| CO | RR | 0.61 (7) | ||||||||||||||||

| DT | 0.74 (10) | 0.65 (10) | ||||||||||||||||

| YO | 0.15 (38) | 0.37 (38) | 0.18 (48) | |||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| NO2 | GT | 0.66 (0.9) | 0.54 (7) | 0.60 (10) | 0.18 (39) | |||||||||||||

| SD | 0.53 (10) | 0.45 (14) | 0.51 (8) | 0.12 (47) | 0.77 (9) | |||||||||||||

| TU | 0.58 (13) | 0.51 (10) | 0.58 (4) | 0.16 (48) | 0.80 (12) | 0.75 (12) | ||||||||||||

| CN | 0.32 (24) | 0.22 (27) | 0.27 (17) | 0.08 (61) | 0.46 (23) | 0.53 (15) | 0.45 (20) | |||||||||||

| YO | 0.14 (38) | 0.32 (38) | 0.12 (48) | 0.71 (0) | 0.13 (39) | 0.13 (47) | 0.09 (48) | 0.11 (61) | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| O3 | JS | 0.17 (0) | 0.14 (7) | 0.20 (10) | 0.16 (38) | 0.38 (1) | 0.39 (10) | 0.42 (13) | 0.14 (24) | −0.06 (38) | ||||||||

| CA | 0.20 (5) | 0.18 (11) | 0.22 (8) | 0.19 (42) | 0.42 (5) | 0.45 (5) | 0.46 (12) | 0.19 (19) | −0.03 (42) | 0.98 (5) | ||||||||

| SD | 0.21 (10) | 0.19 (14) | 0.23 (8) | 0.16 (47) | 0.42 (9) | 0.43 (0) | 0.46 (12) | 0.16 (15) | −0.03 (47) | 0.96 (10) | 0.98 (5) | |||||||

| CN | 0.26 (24) | 0.18 (27) | 0.28 (17) | 0.17 (61) | 0.48 (23) | 0.52 (15) | 0.53 (20) | 0.31 (0) | −0.03 (61) | 0.88 (24) | 0.92 (19) | 0.92 (15) | ||||||

| YO | 0.25 (38) | 0.22 (38) | 0.23 (48) | 0.24 (0) | 0.48 (39) | 0.49 (47) | 0.50 (48) | 0.23 (61) | 0.08 (0) | 0.87 (38) | 0.85 (42) | 0.84 (47) | 0.79 (61) | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| PM2.5 | JS | 0.43 (0) | 0.39 (7) | 0.40 (10) | 0.28 (38) | 0.45 (1) | 0.35 (10) | 0.41 (13) | 0.17 (24) | 0.03 (38) | 0.63 (0) | 0.64 (5) | 0.63 (10) | 0.63 (24) | 0.57 (38) | |||

| SD | 0.28 (10) | 0.31 (14) | 0.30 (8) | 0.29 (47) | 0.37 (9) | 0.31 (0) | 0.36 (12) | 0.14 (15) | 0.03 (47) | 0.60 (10) | 0.63 (5) | 0.61 (0) | 0.61 (15) | 0.53 (47) | 0.88 (10) | |||

| DHC | 0.28 (12) | 0.33 (6) | 0.31 (8) | 0.31 (44) | 0.34 (11) | 0.26 (15) | 0.34 (5) | 0.17 (25) | 0.08 (44) | 0.55 (12) | 0.57 (13) | 0.55 (15) | 0.55 (25) | 0.49 (44) | 0.88 (12) | 0.84 (15) | ||

| YO | 0.18 (38) | 0.24 (38) | 0.17 (48) | 0.35 (0) | 0.24 (39) | 0.18 (47) | 0.25 (48) | −0.01 (61) | 0.05 (0) | 0.64 (38) | 0.65 (42) | 0.63 (47) | 0.58 (61) | 0.62 (0) | 0.86 (38) | 0.82 (47) | 0.82 (44) | |

Air monitoring sites include Jefferson St (JS), Georgia Tech (GT), Confederate Ave (CA), Roswell Rd (RR), South Dekalb (SD), Dekalb Tech (DT), Doraville Health Center (DHC), Tucker (TU), Conyers (CN), and Yorkville (YO)

Emergency Department and Socioeconomic Data

Over the 1998–2004 time period, our database contained 7,616,029 ED visits, including 267,995 visits for circulatory disease (daily mean = 114.3 visits). Table 4 presents mean daily counts and demographic data for each geographic subpopulation living within five miles of each air monitoring site. ED visits for circulatory disease were predominantly made by adults and the elderly (mean age = 60.3 years), with some variation across the geographic subpopulations. Mean daily visit counts (ranging from 5–8 visits/day) and racial composition (ranging from 10–79% Black) also varied across the geographic subpopulations. The visit counts for patients living within five miles of the rural monitors (CN and YO) were very low (less than 2 visits/day), which precluded these populations from being examined in the epidemiologic subpopulation analyses.

Table 4.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the entire population and for each geographic subpopulation.

| Circulatory ED Visitsa | SES Indicatorsb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily N | Age | Raced | %BP | %PA | %HS | Income | ||||

| Populationc | # ZIP Codes | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | %B | %O | # ZIP Codese | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Entire | 225 | 114.3 (26.4) | 60.3 (18.7) [0.13]f | 28.2 [13.5] | 6.0 | |||||

| <=5 mi JS | 15 | 8.3 (3.4) | 61.3 (18.9) [0.5] | 64.5 [14.7] | 4.9 | 13 | 25.3 (14.5) | 4.5 (3.7) | 79.1 (12.8) | $36,544 ($18,011) |

| <=5 mi CA | 16 | 7.2 (3.2) | 58.0 (18.3) [0.5] | 76.9 [20.8] | 4.3 | 13 | 28.6 (12.8) | 5.9 (3.7) | 71.9 (11.8) | $30,522 ($13,987) |

| <=5 mi RR | 10 | 5.4 (2.5) | 68.8 (19.2) [0.2] | 9.8 [4.1] | 7.0 | 10 | 8.0 (4.0) | 0.7 (0.4) | 92.7 (5.4) | $67,168 ($21,513) |

| <=5 mi SD | 7 | 5.8 (2.8) | 55.8 (17.5) [0.4] | 79.3 [34.7] | 5.1 | 6 | 15.3 (7.1) | 4.4 (2.3) | 75.7 (9.4) | $40,096 ($10,385) |

| <=5 mi DT | 11 | 8.0 (3.7) | 57.6 (19.2) [0.3] | 56.7 [38.9] | 6.0 | 10 | 14.1 (9.6) | 3.0 (2.1) | 83.6 (10.0) | $43,892 ($8,992) |

| <=5 mi DHC | 8 | 4.7 (2.5) | 65.1 (18.8) [0.11] | 11.8 [10.2] | 9.6 | 8 | 9.8 (3.5) | 1.2 (0.4) | 85.3 (7.8) | $56,692 ($12,368) |

| <=5 mi TU | 8 | 5.3 (2.9) | 57.4 (19.6) [0.13] | 33.9 [23.8] | 12.6 | 8 | 15.2 (10.1) | 2.5 (2.4) | 78.2 (8.6) | $44,807 ($11,410) |

| <=5 mi CN | 3 | 0.84 (0.95) | 62.5 (16.9) [0.05] | 15.7 [45.1] | 1.8 | 1 | 3.4 (.) | 0.7 (.) | 88.4 (.) | $63,910 (.) |

| <=5 mi YO | 1 | 0.20 (0.45) | 58.6 (18.3) [0.00] | 8.2 [2.5] | 1.3 | 1 | 13.7 (.) | 2.5 (.) | 67.5 (.) | $35,407 (.) |

Circulatory ED visits for the time period 08/01/1998–12/31/2004 (N=2345 days)

SES indicator data from Census 2000: %BP=percent below poverty; %PA=percent on public assistance; %HS=percent with high school graduation; Income=median population housing income

Subpopulations include all patients residing within five miles of Jefferson St (JS), Confederate Ave (CA), Roswell Rd (RR), South Dekalb (SD), Dekalb Tech (DT), Doraville Health Center (DHC), Tucker (TU), Conyers (CN), and Yorkville (YO)

%B=mean percent of visits by Black patients; %O=mean percent of visits by Hispanic and other races/ethnicities

Census data are missing for several ZIP codes that are included in ED database

Square brackets indicate percent unknown age and percent unknown race

Among the urban subpopulations, poverty (%BP) and public assistance (%PA), and educational attainment (%HS) and income were highly correlated (r=0.93 and 0.91, respectively). %BP was negatively correlated with both %HS (r=−0.63) and income (r=−0.85), indicating the relationship between higher poverty and lower education and incomes in Atlanta. Using these measures, SES was typically lowest in the urban center and rural areas and highest in suburban areas.

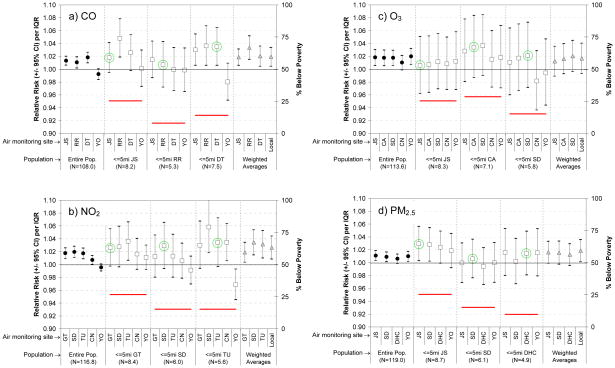

Epidemiologic Results – Entire Population

The results of epidemiologic models predicting ED visits for circulatory disease in the entire study population are presented on the far left side of each graph in Figure 2 (closed circles), and in Table S1 (supplementary material). When using pollutant data from the central sites (i.e., JS and GT) as measures of population exposure, we observed significant positive associations between circulatory visits and each pollutant (range of relative risks: 1.011–1.018 per IQR increase in pollutant concentration), which are consistent with those observed in our previous analyses (Metzger et al., 2004). The results for CO and NO2 are also consistent with traffic-related air pollution effects observed in our epidemiologic analyses using source-apportioned PM2.5 data (Sarnat et al., 2008). We found consistent results for all pollutants when using data from the other urban monitoring sites, located within 12 miles of the central sites, as measures of population exposure. When using data from the most rural site (YO), located 38 miles from the central sites, we also found consistent results for the spatially homogeneous pollutants, O3 and PM2.5. We did not find consistent results, however, for models examining effects associated with spatially heterogeneous pollutants, CO and NO2, when using data from YO. For these models, associations were low in magnitude and consistent with the null hypothesis of no association.

Figure 2.

Associations between current day ambient air pollutants and circulatory ED visits: a) CO, b) NO2, c) O3, and d) PM2.5.

● = results of entire population analyses

□ = results of geographic subpopulation analyses

= results of geographic

subpopulation analyses using local (i.e., closest) monitoring site data

= results of geographic

subpopulation analyses using local (i.e., closest) monitoring site data

= weighted averages of

geographic subpopulation results, where the “local” weighted

averages provide overall estimates for the relative risk using the local site

pollution data across the geographic subpopulations for each pollutant (i.e.,

overall estimates of the circled results) and “site-specific”

weighted averages provide overall estimates of results obtained from using the

other urban sites as central monitors for the same geographic

subpopulations.

= weighted averages of

geographic subpopulation results, where the “local” weighted

averages provide overall estimates for the relative risk using the local site

pollution data across the geographic subpopulations for each pollutant (i.e.,

overall estimates of the circled results) and “site-specific”

weighted averages provide overall estimates of results obtained from using the

other urban sites as central monitors for the same geographic

subpopulations.

= mean % below

poverty of geographic subpopulations (on secondary y-axis)

= mean % below

poverty of geographic subpopulations (on secondary y-axis)

IQR = interquartile range (approximate IQRs used for weighted average relative risks: CO = 1 ppm, NO2 = 20 ppb, O3 = 25 ppb, PM2.5 = 10 μg/m3)

Air monitoring sites = Jefferson St (JS), Georgia Tech (GT), Confederate Ave (CA), Roswell Rd (RR), South Dekalb (SD), Dekalb Tech (DT), Doraville Health Center (DHC), Tucker (TU), Conyers (CN), and Yorkville (YO)

Population = entire population and geographic subpopulations, which include all patients residing within five miles of Jefferson St (JS), Confederate Ave (CA), Roswell Rd (RR), South Dekalb (SD), Dekalb Tech (DT), Doraville Health Center (DHC), Tucker (TU), Conyers (CN), and Yorkville (YO)

N = mean daily circulatory ED visits

Epidemiologic Results – Geographic Subpopulations

Figure 2 also presents the results of models predicting ED visits for circulatory disease in the geographic subpopulations (open squares). Compared to the results of models predicting ED visits for the entire population, these results had much wider confidence intervals, primarily due to fewer visit counts contributing to the analyses. Similar to the results of the entire population analyses, the geographic subpopulation results showed clear urban-rural differences when using CO and NO2 data from the different monitoring sites as different measures of exposure (e.g., associations were lowest in magnitude when using pollutant data from YO).

To aid in determining whether distance between monitoring sites and geographic subpopulations impacted epidemiologic results within the urban area, we calculated weighted averages of the geographic subpopulation results (Figure 2, shaded triangles). The “local” weighted averages provided overall estimates for the relative risk using the local site pollution data across the geographic subpopulations for each pollutant (i.e., overall estimates of the circled results in Figure 2). We compared these estimates with corresponding results obtained using the other urban sites as central monitors for the same geographic subpopulations. Weighted average results of models using local monitoring data were very similar to those using data from the other urban monitoring sites suggesting that within the urban area distance between monitoring sites and subpopulations did not affect our epidemiologic results.

Discussion

Here, we present the results of time-series analyses of ambient air pollution and ED visits for circulatory disease in geographic subpopulations in Atlanta, Georgia, using air pollution data from monitors located in different regions of the study area as alternative measures of exposure. In doing so, we offer a method for evaluating the impacts of an important component of exposure measurement error on air pollution health risk estimates in time-series analyses. Specifically, the method addresses the component of measurement error related to spatiotemporal variability in ambient air pollution concentrations when using fixed site ambient monitoring data to estimate air pollution exposures. By comparing the results of models that use different exposure metrics for the same geographic subpopulation, our method effectively controls for the potential modifying effects of population characteristics.

In our analysis, we assumed that a greater distance between the air pollution monitor used as the measure of exposure and the geographic subpopulation would result in a greater amount of exposure measurement error, particularly for pollutants displaying spatiotemporal variability. Thus, differences in estimated relative risks when different air pollution monitors are used may serve to illustrate the degree of exposure measurement error. Classically, if exposure measurement error is non-differential with respect to a health outcome, we expect the bias to be towards the null when using an exposure measure containing error. According to this model, if the health outcome is caused by the exposure, using a more refined measure of exposure should result in less bias towards the null. For example, a model using data from a local monitoring site as the measure of exposure for a specific geographic subpopulation may yield higher estimated relative risks than a model using non-local data due to lower exposure measurement error, assuming that the correlation between measured ambient concentrations and unmeasured, true average population exposure is higher when the distance between the monitoring site and the population is small (Wilson et al., 2007). Comparing estimated relative risks is a crude way to evaluate measurement error, but descriptive comparisons may be informative. For example, in Figure 2, we compared the relative risks using different measures of exposure within each geographic subpopulation (e.g., for CO, we compared the four results obtained for the JS population, using monitoring data from JS, RR, DT, and YO). We anticipated that the distance between the population and the monitoring sites would provide an indication of exposure measurement error and would thus dictate the observed associations for spatiotemporally heterogeneous pollutants (i.e., CO and NO2), with strongest associations anticipated for each population when paired with its closest monitoring site (circled results in Figure 2).

Our results suggest that the impact of monitoring site location and distance between monitoring sites and the population under study on observed relative risk estimates depends on the pollutant of interest, as expected. For spatially homogeneous pollutants (i.e., O3 and PM2.5), relative risk estimates were generally similar regardless of the monitoring site used as the exposure measure and regardless of distance between monitoring site and population. In contrast, for spatially heterogeneous pollutants (i.e., CO and NO2), estimated associations varied by monitoring site location, particularly when the exposure measure included a rural monitoring site located far (e.g., greater than 30 miles) from the population center of interest. For example, associations that were observed using central site data for CO and NO2 were not observed when using data from the most rural site as the measure of exposure.

Within the urban area, however, distances (e.g., less than 20 miles) between monitoring sites and geographic subpopulations did not meaningfully impact the estimates for any pollutant. Weighted averages of associations using local monitoring data (located within five miles of each subpopulation) were similar to those using data from other urban monitoring sites (located within 10–20 miles of the populations). If closer residential proximity to an ambient monitoring site provides better exposure assessment, as is often assumed to be the case (Chen et al., 2007; Jerrett et al., 2004; Wilson et al., 2007), we would have expected to observe larger relative risks when using local monitoring data than non-local monitoring data in the current analysis. These results suggest that, within urban Atlanta, use of local monitoring data as opposed to other urban monitoring data did not significantly modify exposure estimation for our pollutants of interest.

Based on our results, it appears that urban monitors served as similar surrogates of population exposures to CO and NO2, and were better surrogates of these pollutants than rural monitors in our study. For CO and NO2, the positioning of urban monitors may allow them to pick up specific sources (e.g., background traffic) that are more relevant to the health of the population compared to local impacts near rural sites. For O3 and PM2.5, all monitors yielded very consistent epidemiologic results given the fact that monitor siting criteria varied among our monitoring sites (Table 1).

It is important to note that the five-mile radii used to define subpopulations in this analysis did not allow for highly refined exposure assessment to specific pollutant components associated with individual sources, such as traffic, whose concentrations vary considerably over short distances from roadways (100’s of meters) (Zhu et al., 2002). Significant spatial variation in CO and NO2 pollutant concentrations within the five-mile capture areas may have reduced our ability to refine exposures sufficiently to observe substantial impacts of residential proximity to monitoring sites on our epidemiologic results. Other studies have indeed found higher relative risks when using more spatially-refined estimates of exposure compared with using data from central sites (Jerrett et al., 2005). Moreover, data from certain monitors may not have been the most representative of corresponding local populations because of very local impacts specific to the monitor, such as wind or point sources.

Another reason for the lack of consistent differences in results when using alternative (urban) measures of exposure may be due to the issue of subject mobility. Local monitoring data, assigned to patients based on their residential ZIP codes, may not ultimately have improved exposure assessment in our study due to time-activity patterns that take individuals away from their location of residence for much of the day. While time-activity studies show that people spend approximately 70% of their time inside their homes (Leech et al., 2002), the location of time spent away from home in Atlanta may be farther compared to studies of smaller geographic scale. As part of the Strategies for Metropolitan Atlanta’s Regional Transportation and Air Quality (SMARTRAQ) study, Frank and colleagues (2004) reported the results of an activity-based survey of 8,000 households in 2001, with participants recruited from different land use types, household sizes, and incomes (Frank et al., 2004). The authors found that the per capita daily vehicle miles traveled from home to work was 16.5 miles, with lower estimates for central counties (e.g., 12.2–13.8 miles for DeKalb and Fulton) than for outlying counties (e.g., 31.6 miles for Paulding). Therefore, our five-mile radii may not have sufficiently captured the location of where patients spend their time throughout the day.

Differences in population characteristics, such as demographic or socioeconomic factors, cannot explain differences in our epidemiologic results when using alternative exposure measures for the same geographic subpopulation. They may, however, explain differences in results between different geographic subpopulations paired with their respective local sites (e.g., comparing circled results in Figure 2). Our demographic and SES data suggest that the geographic subpopulations differed with respect to these indicators (Table 4) and thus had potentially different susceptibilities to air pollution. However, we did not find a consistent link between the measured population characteristics and magnitude of the local site effect estimates. Our comparison was limited by having only three results for each between-subpopulation comparison for each pollutant. Heterogeneity in the population characteristics within each geographic subpopulation as well as random variability due to small sample size may also have limited our ability to observe any potential effect.

As such, our results differ from other recent findings. Population characteristics, particularly SES (Cakmak et al., 2006; Jerrett et al., 2004; O’Neill et al., 2003; Zeka et al., 2006), have been shown previously to impact the magnitude of observed associations between air pollution and health. In a geographic subpopulation study most similar to the current one, Jerrett et al. (2004) conducted a “zonal” analysis for associations between PM and sulfur dioxide and mortality in Hamilton, Canada, dividing the study area into five zones (Jerrett et al., 2004). They found that zonal estimates were from 1/3 to 3 times higher than regional (entire population) estimates for both pollutants. They also found that the zone with the highest SES displayed no effect in any models, whereas the zone with the lowest SES had the highest effects.

Our current analysis demonstrates a method for examining the impacts of exposure measurement error relating to spatiotemporal heterogeneity in air pollutant concentrations on time-series health effect estimates, while controlling for population characteristics. In Atlanta, we found that monitoring site location and the distance of a monitoring site to a population of interest did not meaningfully impact estimated associations for any pollutant when using data from urban sites located within 20 miles from the population center under study. However, for CO and NO2, these factors were important when using data from sites located greater than 30 miles from the population center, likely due to exposure measurement error. Our results suggest that data from a rural site (Yorkville), the most distant site from our central, downtown monitors, introduced a substantial degree of exposure measurement error for estimating exposures to CO and NO2. Using data from the urban monitors led to less exposure measurement error for our study population, and we found no important difference between these monitors for estimating associations for CO and NO2. O3 and PM2.5 data from any monitoring site appeared to be similarly representative of population exposure.

These findings lend support to the use of limited ambient monitoring as a surrogate of population exposures in time-series settings. However, it is important to note that specific geographical features, source types and resulting pollutant characteristics in Atlanta may influence the generalizability of our results to other locales. Atlanta provides a large and relatively flat geographic study area (e.g., a 20-county, 7964 sq. mile) whose population is distributed in a concentric pattern around an urban core, with air pollution largely arising from power plants and traffic sources. The impact of distance between monitoring sites and subpopulations may be more prominent in areas with more spatial heterogeneity in pollutant levels than observed in Atlanta (e.g., due to differences in geographical features and/or geographical distribution of sources).

We did not attempt to examine the total impact of exposure measurement error in this analysis, which may in part explain differences in observed relative risks within and between pollutants. While we explored the effects of exposure error among different pollutants, we did so only from the perspective of ambient spatiotemporal distributions. We did not consider several other factors that could potentially influence differences in health effect estimates, including differential instrument error between monitors and spatial variation of pollutant-specific personal-ambient relationships (e.g., due to differential infiltration patterns).

Overall, the current analysis supports use of pollutant data from urban central sites in Atlanta and similar cities to assess ambient exposures for geographically dispersed study populations, even for spatially heterogeneous pollutants (Metzger et al., 2004; Peel et al., 2005; Sarnat et al., 2008; Tolbert et al., 2007). In addition, our findings suggest the need to balance the advantages of improved exposure assessment that may hold if a smaller area is studied, with the increased variance of estimates that would result, in comparison with study of a larger area with more people. Refining exposure assessment by limiting the population of interest to obtain more accurate local exposure estimates will increase the potential for random error, which could mask the association of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to Emory University from the U.S. EPA (R82921301-0), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES11294), and the Electric Power Research Institute (EP-P27723/C13172 and EP-P4353/C2124), as well as to the Georgia Institute of Technology from the U.S. EPA (RD832159, RD831076 and RD830960). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS or U.S. EPA. We would also like to thank Atmospheric Research and Analysis for assistance in using Jefferson Street air quality measurements.

References

- ARA (Atmospheric Research & Analysis, Inc.) [accessed 20 August 2007];SouthEastern Aerosol Research and Characterization Study. 2007 Available: http://www.atmospheric-research.com/

- Ballester F, Rodriguez P, Iniguez C, Saez M, Daponte A, Galan I, Taracido M, Arribas F, Bellido J, Cirarda FB, Canada A, Guillen JJ, Guillen-Grima F, Lopez E, Perez-Hoyos S, Lertxundi A, Toro S. Air pollution and cardiovascular admissions association in Spain: results within the EMECAS project. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60(4):328–336. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.037978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell ML, O’Neill MS, Cifuentes LA, Braga ALF, Green C, Nweke A, Rogat J, Sibold K. Challenges and recommendations for the study of socioeconomic factors and air pollution health effects. Environ Sci Policy. 2005;8(5):525–533. [Google Scholar]

- Butler AJ, Andrew MS, Russell AG. Daily sampling of PM2.5 in Atlanta: results of the first year of the assessment of spatial aerosol composition in Atlanta study. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2003;108:8415. [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak S, Dales RE, Judek S. Respiratory health effects of air pollution gases: Modification by education and income. Arch Environ Occup H. 2006;61(1):5–10. doi: 10.3200/AEOH.61.1.5-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LP, Mengersen K, Tong SL. Spatiotemporal relationship between particle air pollution and respiratory emergency hospital admissions in Brisbane, Australia. Sci Total Environ. 2007;373(1):57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank L, Chapman J, McMillen S, Carpenter A. Performance Measures for Regional Monitoring. Final report to the Georgia Regional Transportation Authority for the SMARTRAQ study. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DA, Edgerton E, Hartsell B, Jansen J, Burge H, Koutrakis P, Rogers C, Suh H, Chow J, Zielinska B, McMurry P, Mulholland J, Russell A, Rasmussen R. Air quality measurements for the aerosol research and inhalation epidemiology study. J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 2006;56(10):1445–1458. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, De Leon S, Thurston GD, Nadas A, Lippmann M. Monitor-to-monitor temporal correlation of air pollution in the contiguous US. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2005;15(2):172–184. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Brook J, Kanaroglou P, Giovis C, Finkelstein N, Hutchison B. Do socioeconomic characteristics modify the short term association between air pollution and mortality? Evidence from a zonal time series in Hamilton, Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58(1):31–40. doi: 10.1136/jech.58.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Ma RJ, Pope CA, Krewski D, Newbold KB, Thurston G, Shi YL, Finkelstein N, Calle EE, Thun MJ. Spatial analysis of air pollution and mortality in Los Angeles. Epidemiology. 2005;16(6):727–736. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000181630.15826.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rahkopf D, Subramanian SV. Race/ethnicity, gender, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: a comparison of area-based socioeconomic measures - the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1655–1671. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech JA, Nelson WC, Burnett RT, Aaron S, Raizenne ME. It’s about time: A comparison of Canadian and American time-activity patterns. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2002;12(6):427–432. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger KB, Tolbert PE, Klein M, Peel JL, Flanders WD, Todd K, Mulholland JA, Ryan PB, Frumkin H. Ambient air pollution and cardiovascular emergency department visits. Epidemiology. 2004;15(1):46–56. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000101748.28283.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC (National Research Council) Research Priorities for Airborne Particulate Matter: I. Immediate Priorities and a Long-Range Research Portfolio. Washington, DC: Committee on Research Priorities for Airborne Particulate Matter, National Research Council, National Academy Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill MS, Jerrett M, Kawachi L, Levy JL, Cohen AJ, Gouveia N, Wilkinson P, Fletcher T, Cifuentes L, Schwartz J. Health, wealth, and air pollution: Advancing theory and methods. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(16):1861–1870. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel JL, Tolbert PE, Klein M, Metzger KB, Flanders WD, Todd K, Mulholland JA, Ryan PB, Frumkin H. Ambient Air Pollution and Respiratory Emergency Department Visits. Epidemiology. 2005;16(2):164–174. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000152905.42113.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto JP, Lefohn AS, Shadwick DS. Spatial variability of PM2.5 in urban areas in the United States. J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 2004;54(4):440–449. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2004.10470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnat JA, Marmur A, Klein M, Kim E, Russell AG, Sarnat SE, Mulholland JA, Hopke PK, Tolbert PE. Fine particle sources and cardiorespiratory morbidity: an application of chemical mass balance and factor analytical source-apportionment methods. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(4):459–466. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnat SE, Klein M, Peel JL, Mulholland JA, Sarnat JA, Flanders WD, Waller LA, Tolbert PE. Spatial considerations in a study of ambient air pollution and cardiorespiratory emergency department visits. Epidemiology. 2006;17:S242. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard L, Slaughter JC, Schildcrout J, Liu LJS, Lumley T. Exposure and measurement contributions to estimates of acute air pollution effects. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2005;15(4):366–376. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon P, Baumann K, Edgerton E, Tanner R, Eatough D, Modey W, Marin H, Savoie D, Natarajan S, Meyer MB, Norris G. Comparison of integrated samplers for mass and composition during the 1999 Atlanta Supersites project. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2003;108(D7) [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert PE, Klein M, Metzger KB, Peel J, Flanders WD, Todd K, Mulholland JA, Ryan PB, Frumkin H. Interim results of the study of particulates and health in Atlanta (SOPHIA) J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2000;10(5):446–460. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert PE, Klein M, Peel JL, Sarnat SE, Sarnat JA. Multipollutant modeling issues in a study of ambient air quality and emergency department visits in Atlanta. J Expo Sci Environ Epi. 2007;17:S29–S35. doi: 10.1038/sj.jes.7500625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. CB (U.S. Census Bureau) Census 2000 Summary File 3 Technical Documentation. Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency) [accessed 1 December 2007];Air Quality System. 2007 Available: http://www.epa.gov/ttn/airs/airsaqs/

- Wade KS, Mulholland JA, Marmur A, Russell AG, Hartsell B, Edgerton E, Klein M, Waller L, Peel JL, Tolbert PE. Effects of instrument precision and spatial variability on the assessment of the temporal variation of ambient air pollution in Atlanta, Georgia. J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 2006;56(6):876–888. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellenius GA, Schwartz J, Mittleman MA. Particulate air pollution and hospital admissions for congestive heart failure in seven United States Cities. American Journal of Cardiology. 2006;97(3):404–408. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JG, Kingham S, Pearce J, Sturman AP. A review of intraurban variations in particulate air pollution: Implications for epidemiological research. Atmos Environ. 2005;39(34):6444–6462. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JG, Kingham S, Sturman AP. Intraurban variations of PM10 air pollution in Christchurch, New Zealand: Implications for epidemiological studies. Sci Total Environ. 2006;367(2–3):559–572. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WE, Mar TF, Koenig JQ. Influence of exposure error and effect modification by socioeconomic status on the association of acute cardiovascular mortality with particulate matter in Phoenix. J Expo Sci Environ Epi. 2007;17:S11–S19. doi: 10.1038/sj.jes.7500620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Thomas D, Dominici F, Samet JM, Schwartz J, Dockery D, Cohen A. Exposure measurement error in time-series studies of air pollution: concepts and consequences. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(5):419–426. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeka A, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Individual-level modifiers of the effects of particulate matter on daily mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(9):849–859. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Hinds W, Kim S, Shen S, Sioutas C. Study of ultrafine particles near a major highway with heavy-duty diesel traffic. Atmos Environ. 2002;36(27):4323–4335. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.