Abstract

This research examined whether naturally-occurring self-fulfilling prophecies influenced adolescents’ responsiveness to a substance use prevention program. The authors addressed this issue with a unique methodological approach that was designed to enhance the internal validity of research on naturally-occurring self-fulfilling prophecies by experimentally controlling for prediction without influence. Participants were 321 families who were assigned to an adolescent substance use prevention program that either did or did not systematically involve parents. Results showed that parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention predicted adolescents’ alcohol use more strongly among families assigned to the prevention program that systematically involved parents than to the one that did not. The theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords: Self-fulfilling prophecy, Perceptions, Prevention, Adolescent alcohol use

Psychological theory proposes that people can construct reality through a self-fulfilling prophecy (Jones, 1986). A self-fulfilling prophecy occurs when people cause their initially inaccurate perceptions to become true (Merton, 1948). Numerous investigations have examined the self-fulfilling prophecy process using either experimental or naturalistic research methods (for reviews, see Jussim & Harber, 2005; Snyder, 1984, 1992; Snyder & Stukas, 1999). These methods are typically conceptualized as having complementary strengths. Experimental studies of self-fulfilling prophecies are typically strong with respect to their internal validity, but the findings may not necessarily generalize to the naturalistic environment. Naturalistic studies of self-fulfilling prophecies can complement the potentially low external validity of experiments, but are susceptible to the possibility that their findings may not necessarily reflect self-fulfilling influence. However, there is a way to capitalize on each method’s relative strength with an approach that incorporates key elements of both experimental and naturalistic methods.

We present such an approach in the present article and then apply it to an empirical investigation. Our empirical investigation is itself of interest and importance in that it is the first study to test whether naturally-occurring self-fulfilling prophecies influence the extent to which a prevention program benefits program participants. Specifically, we examined whether parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in an adolescent substance use prevention program had self-fulfilling effects on a prevention program’s effectiveness. We begin by discussing experimental and naturalistic approaches to the study of self-fulfilling prophecies after which we introduce our approach and discuss the empirical investigation in detail.

Self-fulfilling Prophecies: Experimental and Naturalistic Research Methods

In the typical experiment addressing self-fulfilling prophecies, researchers artificially induce inaccurate perceptions in perceivers by providing them with invalid information. Because this approach ensures that perceivers’ perceptions are, on average, inaccurate at the outset, studies that use this approach are typically characterized by a high degree of internal validity. That is, researchers can strongly infer that any subsequent changes that occur in the outcome (relative to a condition in which either no inaccurate perceptions or different inaccurate perceptions were induced) are due to the self-fulfilling influence of the inaccurate perceptions. The findings of this literature have been critically important to the field because they have provided compelling evidence that the self-fulfilling prophecy is a real phenomenon that can occur when perceivers are artificially induced to hold inaccurate perceptions. However, the experimental approach cannot address whether self-fulfilling prophecies occur in people’s natural environments (Jussim, 1989). In the naturalistic environment, perceivers typically have access to valid information that increases the likelihood that their perceptions will be accurate to some extent at the outset (Madon et al., 2001). Because only inaccurate perceptions can be self-fulfilling (Merton, 1948), the availability of valid information reduces the potential for perceivers’ perceptions to be self-fulfilling.

Concerns regarding the external validity of experimental findings have prompted researchers to examine self-fulfilling prophecies in naturalistic contexts (e.g., Buchanan, 2003; Buchanan & Hughes, 2009; Madon, Guyll, Spoth, & Willard, 2004; Madon, Willard, Guyll, Trudeau, & Spoth, 2006; Pomerantz & Dong, 2006; Smith, Jussim, & Eccles, 1999; Trouilloud, Sarrazin, Martinek, & Guillet, 2002; Trouilloud, Sarrazin, Bressoux, & Bois, 2006; for reviews, see Jussim & Eccles, 1995; Jussim, Eccles, & Madon, 1996; Jussim & Harber, 2005). Unlike experiments that artificially induce inaccurate perceptions in perceivers, naturalistic studies focus on the perceptions that perceivers develop naturally. As such, naturalistic studies provide important information about the extent to which self-fulfilling prophecies occur within the context of people’s every day lives. However, as discussed above, because only inaccurate perceptions can be self-fulfilling (by definition), a positive association between perceivers’ naturally-occurring perceptions and a subsequent outcome may not necessarily reflect self-fulfilling influence. Such an association may instead be non-causal in nature. A non-causal association of this sort is referred to in the self-fulfilling prophecy literature as prediction without influence (Madon, Guyll, Spoth, Cross, & Hilbert, 2003), predictive validity without influence, or accuracy (Jussim, 1991) because it reflects the extent to which perceivers’ perceptions predicted an outcome without having caused it.

Reflection-Construction Model (Jussim, 1991)

The reflection-construction model (Jussim, 1991) highlights the important role of prediction without influence as it relates to naturalistic studies of self-fulfilling prophecies. According to the model, a positive association between perceivers’ perceptions and a subsequent outcome can reflect both prediction without influence and self-fulfilling influence to varying degrees. The model distinguishes between these sources of influence by controlling for relevant background controls that are expected to be predictive of the outcome. For example, if the outcome was adolescents’ alcohol use, then a good set of background controls would include adolescents’ past alcohol use, expectations for future alcohol use, access to alcohol, and friends’ alcohol use, etc. In terms of the model, prediction without influence is defined as that portion of perceivers’ perceptions that correlate with the background controls. Self-fulfilling influence, by contrast, is defined as that portion of perceivers’ perceptions that uniquely predict the outcome after accounting for the background controls.

Consistent with the tenets of this model, nearly all naturalistic studies of self-fulfilling prophecies have attempted to isolate self-fulfilling influence from prediction without influence by examining the association between perceivers’ perceptions and a subsequent outcome in the context of an analytic model that includes background variables as controls. For example, studies examining the self-fulfilling effects of parents’ and teachers’ perceptions on adolescents’ academic achievement typically include as background variables students’ previous achievement, effort, and motivation (e.g., Alvidrez & Weinstein, 1999; Jussim & Eccles, 1992; Scherr & Madon, 2011; see Jussim & Harber, 2005 for a review). This approach supports a self-fulfilling prophecy to the degree that perceivers’ perceptions predict the outcome above and beyond that which is predicted by the background control variables (Jussim, 1991). Although controlling for background variables can be effective at minimizing the degree to which prediction without influence stands as a viable alternative to a self-fulfilling prophecy interpretation, it cannot rule it out altogether. This is because no matter how many background control variables are included an analysis, it is always possible that a relevant one was omitted. When this happens, perceivers’ self-fulfilling effects are overestimated precisely because prediction without influence was underestimated (Jussim, 1991).

Methodological Approach

The current research presents a novel methodological approach to address the potential role of prediction without influence as it relates to naturally-occurring self-fulfilling prophecies. This approach is designed to disentangle prediction without influence from self-fulfilling influence within the naturalistic environment without having to consider the possibility that one or more relevant background variables was omitted as a control. The basis for the approach stems from the three steps that are involved in the self-fulfilling prophecy process.

There is broad consensus that a self-fulfilling prophecy necessarily involves three, core sequential steps (Jones, 1986; Snyder, 1984): First, a perceiver must hold an inaccurate perception. Second, the perceiver must behave consistently with the inaccurate perception. Third, the perceiver’s behavior must alter the outcome of interest in such a way as to make it conform to the originally inaccurate perception. As suggested by this framework, the potential for perceivers’ inaccurate perceptions to have a self-fulfilling effect on a subsequent outcome rests on perceivers’ behaviors. That is, a self-fulfilling prophecy is only possible to the degree that perceivers can behave consistently with their perceptions. The less opportunity perceivers have to behave consistently with their perceptions, the less potential they have to shape an outcome through the process of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Our approach draws on this framework as well on prior research related to the partitioning of variance components within social relationships (Berman, 1980; Howard, Orlinsky, & Perilstein, 1976) to disentangle prediction without influence from self-fulfilling influence. Specifically, our approach experimentally manipulates the opportunities that perceivers have to behave consistently with their perceptions. By manipulating this factor, our approach varies how likely perceivers are to complete the second step of the self-fulfilling prophecy process, thereby ultimately affecting their potential for self-fulfilling influence. In its most simple form, our approach involves two conditions: (1) a facilitative condition in which the relative opportunities that perceivers have to behave consistently with their perceptions are high, and (2) an inhibitive condition, in which the relative opportunities that perceivers have to behave consistently with their perceptions are low. Because the facilitative condition affords perceivers greater opportunities to behave consistently with their perceptions than the inhibitive condition, perceivers in the facilitative condition are more likely to complete the second step of the self-fulfilling prophecy process. As a result, their potential for self-fulfilling influence is greater than the potential for self-fulfilling influence among perceivers in the inhibitive condition.

Disentangling prediction without influence from self-fulfilling influence is accomplished by comparing the association between perceivers’ perceptions and the outcome across the facilitative and inhibitive conditions. In the facilitative condition, a positive association between perceivers’ perceptions and the outcome can reflect both self-fulfilling influence and prediction without influence to varying degrees. This is because perceivers in this condition have the potential to causally alter the outcome by virtue of behaving consistently with their perceptions (i.e., a self-fulfilling prophecy). These perceivers’ perceptions can also predict the outcome without having caused it simply because their perceptions correlated with background variables that were themselves predictive of the outcome (i.e., prediction without influence).

By contrast, in the inhibitive condition, a positive association between perceivers’ perceptions and the outcome will tend to reflect prediction without influence more than self-fulfilling influence. This is because whereas perceivers in the inhibitive condition have just as much potential as perceivers in the facilitative condition to predict the outcome due to correlations between their perceptions and the background control variables (i.e., prediction without influence), they have less potential for self-fulfilling influence due to the fact that they had fewer opportunities than perceivers in the facilitative condition to behave consistently with their perceptions. Consistent with this reasoning, any positive association that arises between perceivers’ perceptions and the outcome in the inhibitive condition is interpreted by our approach as prediction without influence. Our approach, therefore, supports a self-fulfilling prophecy to the degree that the relation between perceivers’ perceptions and the outcome is stronger among perceivers in the facilitative condition (where perceivers’ opportunities to behave consistently with their perceptions are relatively high) than in the inhibitive condition (where perceivers’ opportunities to behave consistently with their perceptions are relatively low).

However, it is important to point out that our approach cannot guarantee the complete absence of self-fulfilling influence in the inhibitive condition. Indeed, even though perceivers in the inhibitive condition have less potential for self-fulfilling influence than perceivers in the facilitative condition, it may not be feasible in the naturalistic environment for the inhibitive condition to restrict perceivers’ behavioral opportunities to such a degree that their potential for self-fulfilling influence is altogether eliminated. Although at first blush this aspect of our approach may appear problematic, further consideration reveals that it produces a more conservative test of the self-fulfilling prophecy process.

As we explained previously, the traditional approach for accounting for prediction without influence within the naturalistic environment is to include background variables as controls. If all relevant background control variables are included in an analytic model, then any positive association that arises between perceivers’ perceptions and the outcome reflects self-fulfilling influence. However, if one or more relevant background control variables is omitted, then part of the observed association actually reflects prediction without influence, but will nonetheless be interpreted as self-fulfilling influence. Because one can never be certain that all relevant background control variables have been accounted for, the traditional approach is susceptible to underestimating prediction without influence and overestimating self-fulfilling influence (Jussim, 1991).

By contrast, our approach attributes a positive association between perceivers’ perceptions and the outcome in the inhibitive condition entirely to prediction without influence even though some part of that association may have actually been due to self-fulfilling influence. To the extent this occurs, perceivers’ self-fulfilling effects in the facilitative condition are underestimated. This is because, in such cases, more of the association that arises between their perceptions and the outcome is attributed to prediction without influence than is true. In other words, some part of the association between perceivers’ perceptions and the outcome in the facilitative condition that was actually due to self-fulfilling influence is attributed to prediction without influence. Thus, our approach is susceptible to overestimating prediction without influence and underestimating self-fulfilling influence. Because overestimating perceivers’ self-fulfilling effects is rarely desirable, we consider the more conservative test offered by our approach to be a strength.

Empirical Investigation

We applied our approach to an empirical investigation that examined whether the self-fulfilling prophecy process could influence the extent to which a prevention program benefited program participants. Researchers in varied disciplines have demonstrated that people’s naturally-occurring perceptions about treatment correlate positively with their therapeutic outcomes. For example, naturalistic studies have demonstrated that client’s initial perceptions about psychotherapy, and medical patients’ initial perceptions about pain therapy, predicted their therapeutic outcomes in the direction of their initial perceptions (e.g., Dew & Bickman, 2005; Olver, Taylor, & Whitford, 2005). However, the cause of these associations is not clear. Because these studies were not designed to test for self-fulfilling prophecies, they failed to account for prediction without influence. As a result, it is not possible to know if, and to what extent, a self-fulfilling prophecy contributed to clients’ and patients’ responses to treatment.

A primary goal of our research, therefore, was to more rigorously test whether the self-fulfilling prophecy process can influence the extent to which a prevention program benefits program participants by accounting for the effect of prediction without influence. Toward this end, we examined whether parents had a self-fulfilling effect on the effectiveness of an adolescent substance use prevention program. To create a clear conceptual link between parents’ perceptions and the outcome of interest in our research – the effectiveness of the prevention program – we focused our attention on parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in the prevention of adolescent substance use. We did not focus on the more traditional use of perceivers’ expectations about targets, which in our research corresponded to parents’ expectations about their particular adolescents’ likelihood of drinking alcohol. The reason is that parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in the prevention of adolescent substance use are directly linked to a prevention program’s effectiveness through parents’ program-relevant behaviors, whereas parents’ expectations about their particular adolescents’ alcohol use are not.

As an illustration, consider parents who are participating in a family-focused prevention program with their adolescents. Parents who more highly value the involvement of parents in adolescent substance use prevention efforts would likely implement the program’s content at home more effectively than parents who did not as strongly value the involvement of parents in adolescent substance use prevention efforts. These varying program-relevant behaviors should, in turn, influence how effective the program will ultimately be. Presumably, the program would be more effective for those adolescents whose parents more strongly valued parental involvement in adolescent substance use prevention efforts because of the effect this perception would have on their program-relevant behaviors. Thus, parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention and a program’s effectiveness are conceptually linked.

The same is not likely to be true for parents’ expectations about their particular adolescents’ likelihood of drinking alcohol. This is because parents’ expectations about their particular adolescents would not be expected to reliably influence their program-relevant behaviors. In fact, it seems entirely possible that parents with very different expectations about their particular adolescents’ alcohol use may engage in very similar program-relevant behaviors for different reasons. Parents who expect that their adolescents will drink alcohol in the future may work hard to effectively implement a program’s content at home as a way to curb their adolescents’ future alcohol use. However, other parents who do not expect their adolescents to drink alcohol in the future may also work hard to effectively implement a program’s content at home as a way to reinforce abstinence. Thus, parents’ expectations about their particular adolescents’ alcohol use may not reliably influence parents’ program-relevant behaviors and, therefore, would not be expected to alter the program’s effectiveness through a self-fulfilling prophecy. Accordingly, in order to test whether parents can have a self-fulfilling influence on a prevention program’s effectiveness, we used parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention as the variable of interest rather than parents’ expectations about their particular adolescents, the latter of which is not necessarily linked to a prevention program’s effectiveness.

We assessed parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention prior to their adolescents’ participation in one of two empirically supported, universal substance use prevention programs. Because both programs aimed to prevent adolescent substance use, we used adolescents’ alcohol use following the completion of the programs to measure program effectiveness. In one condition, the program systematically involved parents in the intervention. Parents attended program sessions and the content of these sessions was focused both on the adolescents and their parents. As such, there was ample opportunity for these parents’ perceptions to affect their behavior in ways that could influence the program’s effectiveness through a self-fulfilling prophecy. For example, in comparison to parents with more favorable perceptions, those with less favorable perceptions may have been less willing to incorporate skills taught by the program into their family’s lives, thereby reducing how much the program could benefit their particular adolescents.

In addition to having the potential for self-fulfilling influence, these parents also had the potential to predict the program’s effectiveness because of prediction without influence. That is, their perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention may have predicted their adolescents’ alcohol use following the completion of the program, not because of a self-fulfilling prophecy, but rather because their perceptions correlated with background variables that were themselves predictive of their adolescents’ alcohol use. These background variables might include, for example, their adolescents’ previous alcohol use, the alcohol use of their adolescents’ friends, and their adolescents’ own expectations about drinking alcohol in the future. Accordingly, these parents’ perceptions could predict their adolescents’ alcohol use for two reasons: Self-fulfilling influence and prediction without influence. In terms of our approach, therefore, this prevention program condition corresponded to the facilitative condition described earlier.

In the other prevention program condition, the program did not systematically involve parents in the intervention. Although these parents and adolescents could choose to discuss the program with one another outside of the program context, the fact that the program did not include parents in any of the program sessions and focused its content only on the adolescents meant that there was limited opportunity for these parents’ perceptions to affect their behavior in ways that could enhance or undermine the program’s effectiveness on their adolescents’ alcohol use through a self-fulfilling prophecy. Accordingly, the association between these parents’ perceptions and their adolescents’ alcohol use following the completion of the program was used to estimate prediction without influence. In terms of our approach, this prevention program condition corresponded to the inhibitive condition described earlier.

Because the families in our research were randomly assigned to the prevention program conditions and because parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention were assessed before families learned of their prevention program assignment, we could assume with confidence that prediction without influence was equivalent across conditions. Therefore, to disentangle prediction without influence from self-fulfilling influence we examined whether parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention predicted their adolescents’ alcohol use more strongly among families assigned to the program that systematically involved parents than to the one that did not. If such a pattern occurred, then we could be confident that parents assigned to the program that systematically involved parents had a self-fulfilling influence on the program’s effectiveness because the predictive power of their perceptions exceeded that due to prediction without influence which was estimated by the relationship between the perceptions of parents assigned to the program that did not systematically involve parents and their adolescents’ alcohol use. Because our approach accounts for prediction without influence within this latter condition, there is no need to include extensive controls as a way to minimize the viability of prediction without influence as an alternative to a self-fulfilling prophecy interpretation.

Method

Participants

Participants were families who participated in the Capable Families and Youth project (Spoth, Redmond, Trudeau, & Shin, 2002), a longitudinal study designed to prevent adolescent substance use and other problem behaviors. Participants of the Capable Families project were families of seventh graders enrolled in 36 rural schools in 22 contiguous counties in Iowa. Schools included in the study were selected on the basis of school lunch program eligibility (20% or more of households within 185% of the federal poverty level in the school district), school district size (1,200 or fewer), and having all middle school grades taught at a single location. The current study used data obtained from 321 families who had valid data on all of the variables used in the analyses. One adolescent in each family provided data. There were 155 girls and 166 boys, including 304 European Americans, 2 Black/African Americans, 1 Native American, 1 adolescent categorized as “other”, and 13 adolescents for whom ethnicity information was unavailable. At the start of the study, mothers averaged 39 years old, fathers averaged 41 years old, and adolescents averaged 12 years old.

Prevention Program Conditions

Families were assigned to one of two empirically supported, universal, adolescent substance use prevention programs depending on the school attended by the participating adolescent. Schools were randomly assigned to these prevention program conditions. Other families (not examined in this article) were assigned to a control condition (Spoth, Randall, Shin, & Redmond, 2005; Spoth et al., 2002; Spoth, Randall, Trudeau, Shin, & Redmond, 2008). The prevention programs were the Life Skills Training program (n = 179), and the Life Skills Training program in combination with the Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10-14 (n = 142).

The Life Skills Training program (Botvin, 2000) is a 15-session school-based program that is based on social learning (Bandura, 1977) and problem behavior (Jessor & Jessor, 1997) theories. The program prevents adolescent substance use and other problem behaviors by promoting skill development in youth. Three components of skill development are emphasized. These include drug resistance skills (e.g., peer pressure resistance), self-management skills (e.g., stress reduction), and general social skills (e.g., effective communication). Adolescents attended program sessions at their school during classroom periods while they were in the 7th-grade. Each session lasted approximately 40-50 minutes. Schools informed parents that the prevention program was being implemented, but parents did not participate in the program in any systematic, structured, or targeted way.

The Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10-14 (Kumpfer, Molgaard, & Spoth, 1996; Molgaard, Kumpfer, & Fleming,1997) is a 7-session program that is based on family risk and protective factor models (Molgaard, Spoth, & Redmond, 2000). The program prevents adolescent substance use and other problem behaviors by emphasizing skill development in youth and their parents. For youth, the program emphasizes pro-social skills (e.g., effective communication) and peer resistance skills (e.g., stress reduction, peer pressure resistance). For parents, the program emphasizes skills in nurturing, limit setting, and communication. Each session includes a separate, concurrent parent and youth skills-building curriculum followed by a conjoint family curriculum where parents and youth practiced skills learned in their separate sessions. Families in the current study received several incentives for participation in the Strengthening Families Program curricula. These included a free meal at each session and free child care for non-participating children. Participating family members also received a coupon at each session that valued $3.00 for adolescents and $5.00 for parents. There was also a drawing that was rigged so that each participating family received a family game night package that included games and snacks. Finally, participating adolescents received a $25.00 check if their families participated in at least four sessions. In the current sample, 94 (66%) families assigned to this prevention program condition participated in the Strengthening Families Program curricula. For 82 of these families, both the mother and father participated. When only 1 parent participated (n = 12), it was overwhelmingly the mother (n = 11). On average, out of the 7 sessions constituting the Strengthening Families Program, mothers attended 4.39 sessions, fathers attended 3.60 sessions, and adolescents attended 3.99 sessions. Additional information about the prevention programs and their implementation in the Capable Families project is available in Kumpfer et al., 1996; Molgaard et al., 1997; Spoth, Redmond, & Shin, 2001; Spoth et al., 2002.

Assessment Waves

The current study used data obtained at baseline while adolescents were in the 7th-grade (Wave 1), and at a post-test and follow-up that occurred approximately 6 months (post-test; Wave 2, 7th-grade) and 18 months (follow-up; Wave 3, 8th-grade) later. Baseline assessments were obtained before families learned of their prevention program assignment. Participation in the prevention programs occurred between baseline and Wave 2, the 6-month post-test. The 6-month post-test and 18-month follow-up assessed adolescents’ alcohol use.

Attrition

The Capable Families project included 456 families who were assigned to a prevention program condition. Of these, 79 families lacked baseline data on one or more of the variables used in the analyses. An additional 56 families lacked data for the dependent variable of adolescents’ alcohol use, including 17 that who were missing this information at the 6-month post-test and 39 who were missing this information at the 18-month follow-up. Analyses that compared families with incomplete data to those with complete data revealed no significant differences on any of the key baseline variables, ts(375) ≤ 1.03; ps ≥ .31, nor a difference on the 6-month post-test of adolescents’ alcohol use, t (358) = .05; ps = .96.

Procedures

Research staff interviewed parents to obtain demographic information and then administered written questionnaires to family members who completed them individually. Participants were informed that their questionnaire responses were confidential and would not be communicated to other family members. Each participating family member received $10.00 per hour to compensate them for the completion of these questionnaires.

Measures

The questionnaires assessed a large number of variables related to family, peers, and substance use. The current study used questionnaire items that assessed parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention, parents’ expectations about their particular adolescents’ likelihood of drinking alcohol in the future, both assessed at baseline, and adolescents’ alcohol use, assessed at baseline, at a posttest administered shortly following program implementation (approximately 6 months post-baseline), and at a follow-up assessment that was administered one year after the post-test (approximately 18 months post-baseline). The following sections describe these variables in greater detail and provide reliability information. With respect to parents’ responses, the reliability coefficients were calculated across items and parents such that mothers’ individual responses and fathers’ individual responses were both included in each reliability analysis.

Parents’ perceptions

To assess parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention, mothers and fathers individually responded to three items that followed the question stem “To me, participating in a program to help parents prevent child problems such as substance abuse or other difficulties is…” The three items were Valuable, Needed, and Important. Parents responded to these items on 7-point scales with anchors worthless-valuable, not needed-needed, and important-unimportant. Responses to the item assessing importance were reverse scored. Mothers’ and fathers’ responses to these three items were averaged to create one perception variable per family (α = .72). We averaged across mothers’ and fathers’ responses in order to account for the possibility that mothers and fathers might hold conflicting perceptions that could mitigate each other’s self-fulfilling effects. By averaging across mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions we were able to perform a more accurate test of the true self-fulfilling effect that both parents, combined, had on a prevention program’s effectiveness.

Parents’ expectations

Parents’ expectations about their particular adolescents’ likelihood of drinking alcohol was assessed with three items: (1) “On a scale of 1 to 10, please rate how likely you think it is that your child in the study will drink alcohol regularly as a teenager?” with anchors 1 (certain that this will not happen) to 10 (certain that this will happen); (2) “If your child in the study were at a party and one of his or her friends offered him/her an alcoholic beverage, how likely would your child be to just say no and leave?” with anchors 1 (very likely) and 5 (very unlikely); and (3) “If your child in the study were at a party and one of his or her friends offered him/her an alcoholic beverage, how likely would your child be to drink it”, also with scale anchors 1 (very likely) to 5 (very unlikely). Responses to the third item were reverse scored. To combine responses into a single variable, we rescaled the 5-point scale responses into a 10-point scale format (i.e., 1 → 1.0; 2 → 3.25; 3 → 5.5; 4 → 7.75; 5 → 10.0) and then averaged mothers’ and fathers’ responses to yield one score per family (α = .68). Higher values indicate that parents believed their adolescent was more likely to drink alcohol.

Adolescents’ alcohol use

We assessed adolescents’ alcohol use with an index reflecting the frequency of alcohol use across a range of drinking behaviors. These behaviors were assessed with five items. Two of these items were assessed with an open-ended response format: (1) “During the past month, how many times have you had beer, wine, wine coolers, or other liquor?” and (2) “During the past month, how many times have you had three or more drinks (beer, wine, or other liquor) in a row?”. The remaining three items were assessed on 7-point scales with anchors 1 (not at all) and 7 (about every day): (3) “How often do you currently drink alcoholic beverages?”; (4) “How often do you currently drink alcoholic beverages without a parents’ permission?”, and; (5) “How often do you usually get drunk?”. To calculate adolescents’ alcohol use, we dichotomized adolescents’ responses to each of these items by assigning a value of 0 to responses indicating no drinking (i.e., open ended responses equal to 0 and scale responses equal to 1) and assigning a value of 1 to responses indicating some amount of drinking (i.e., open ended responses greater than 0 and scale responses of 2 through 7). We dichotomized responses to the alcohol use items because doing so created a common metric and reduced the influence of extreme responses. The coded responses were then summed to create the index reflecting the frequency of adolescents’ alcohol use (αBaseline = .87; αPosttest = .89; α18-month follow-up = .89). Consistent with its use in previous publications (Madon et al., 2003, 2004, 2006, 2008; Willard, Madon, Guyll, Spoth, & Jussim, 2008), this measure reflects drinking behavior that can vary across time, thereby making it well-suited to testing for self-fulfilling prophecies. Other studies that tested for intervention effects with the full sample of participants in the Capable Families project, for which the current outcome was not available, focused on delayed onset of alcohol use and other available alcohol measures, such as past month alcohol use (e.g., Spoth et al., 2002, 2005, 2008). Adolescents’ alcohol use in the current study could range from 0 to 5. Higher values indicate more frequent alcohol use.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations among the individual level variables. Table 2 presents this information separately by prevention program condition.

Table 1.

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Adolescents’ baseline alcohol use | — | .52** | .33** | .09 | .22** | .09 |

| (2) Adolescents’ alcohol use at the posttest | — | .50** | .09 | .19** | −.05 | |

| (3) Adolescents’ alcohol use at the 18-month follow-up | — | .05 | .24** | −.05 | ||

| (4) Prevention program condition | — | −.12* | .01 | |||

| (5) Parents’ expectations about their adolescents’ likelihood of drinking alcohol | — | .01 | ||||

| (6) Parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention |

— | |||||

|

| ||||||

| M | .21 | .35 | .60 | 56%a | 3.31 | 6.34 |

| SD | .80 | 1.05 | 1.34 | — | 1.27 | .69 |

Note: N = 321. Prevention program condition was coded as 1 and 0 for families assigned to the prevention program that did and did not systematically involve parents, respectively.

Value equals percentage of families assigned to the prevention program that did not systematically involve parents. M refers to the mean. SD refers to the standard deviation.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics by prevention program condition

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Adolescents’ baseline alcohol use | — | .71** | .36** | .11 | −.01 |

| (2) Adolescents’ alcohol use at the posttest | .39** | — | .47** | .23** | .00 |

| (3) Adolescents’ alcohol use at the 18-month follow-up | .31** | .53** | — | .25** | .04 |

| (4) Parents’ expectations about their adolescents’ likelihood of drinking alcohol | .37** | .18* | .26** | — | −.03 |

| (5) Parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention |

.17* | −.10 | −.13 | .06 | — |

|

| |||||

|

No parental involvement

M SD |

.15 .67 |

.26 .86 |

.54 1.20 |

3.44 1.32 |

6.33 .66 |

|

Parental involvement

M SD |

.29 .94 |

.46 1.25 |

.68 1.50 |

3.13 1.19 |

6.34 .73 |

Note: N = 321. Correlations above the diagonal are based on data from families in the prevention program condition that did not systematically involve parents. Correlations below the diagonal are based on data from families in the prevention program condition that did systematically involve parents. M refers to the mean. SD refers to the standard deviation.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

Intervention effects

Spoth et al. (2002) found significant intervention program effects for delayed alcohol initiation at the 18-month follow-up – the primary targeted outcome; no earlier intervention program effects were expected or hypothesized. The present study complements this work by examining whether parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention had self-fulfilling effects on the effectiveness of a substance use prevention program in which their adolescents participated, an issue that has important implications for understanding the mechanisms of intervention effects.

Hierarchically structured data

The data were hierarchically structured with families clustered within schools, and schools matched on risk factors (i.e., family social class, family risk, school grade structure, geographic distance of community to a city) to form blocks of three schools each. Traditional data analytic procedures are not appropriate for hierarchically structured data because they assume independence of individual observations and, as a result, tend to underestimate standard errors and bias significance tests toward rejection of the null hypothesis (Cochran, 1977; Kreft & de Leeuw, 1998). To account for the hierarchical structure of the data we performed analyses using SAS PROC MIXED (Littell, Milliken, Stroup, & Wolfinger, 1996). This mixed-model analytic approach corrects for the effects related to clustering by adjusting the standard errors associated with the parameter estimates. In the analyses, we utilized restricted maximum likelihood estimation and identified blocks and schools nested within blocks as random effects that influenced intercept values but not the coefficients of the individual level variables.

The outcome was adolescents’ post-intervention alcohol use at the posttest and 18-month follow-up. Accordingly, repeated measures on the outcome were defined as occurring at these two points in time, thereby enabling us to test whether the passage of time predicted changes in the outcome. Baseline alcohol use was assessed prior to the intervention and was included as a predictor variable in the model. To minimize multicollinearity, we mean-centered the variables prior to performing the analyses (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). The results reported in the text reflect standardized coefficients. Table 3 presents the results in terms of both standardized and unstandardized coefficients.

Table 3.

Summary of multi-level repeated measures analysis for prediction of adolescents’ alcohol use

| Variable | β | SE | b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention program condition | .13 | .12 | .13 |

| Adolescents’ baseline alcohol use | .62** | .06 | .47** |

| Parents’ expectations about their adolescents’ likelihood of drinking alcohol | .12** | .04 | .10** |

| Parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention | .02 | .09 | .03 |

| Prevention program condition × parents’ perceptions | −1.21** | .14 | −.38** |

| Time | .25** | .07 | .25** |

Note: N = 321. The dependent variable was adolescents’ alcohol use. β refers to the standardized coefficient. SE refers to the standard error. b refers to the unstandardized coefficient. Prevention program condition was coded as 1 and 0 for families assigned to the prevention program that did and did not systematically involve parents, respectively. The standardized estimate for prevention program condition reflects the standard deviation change in adolescents’ alcohol use across the two prevention program conditions. The standardized estimate for time reflects the standard deviation change in adolescents’ alcohol use that occurred from the posttest to the 18-month follow-up.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

Main Analyses

The analytic model used to predict adolescents’ alcohol use included the higher order cluster variable of schools nested within blocks. The fixed effects portion of the model included prevention program condition (coded as 1 and 0 for the condition that did and did not systematically involve parents, respectively), plus parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention, and the interaction term of prevention program condition with this parent perception variable. The model also included parents’ expectations about their particular adolescents’ likelihood of drinking alcohol in the future. This latter variable was included to ensure that any self-fulfilling effect attributed to parent’s perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention would not be confounded with a separate self-fulfilling prophecy stemming from parents’ expectations about their own child – expectations that are conceptually distinct from their perceptions about prevention. Finally, the model included adolescents’ baseline alcohol use as a covariate in order to assess post-intervention changes in adolescents’ alcohol use, which corresponded to our operationalization of the programs’ effectiveness.

Results revealed no significant hierarchical clustering of the individual level data within schools (z = 1.17; p =.12) and no main effect of prevention program condition (ß= .13; p = .28; SE = .12). This latter finding indicates that the prevention programs did not differentially predict changes in adolescents’ alcohol use among our sample. Readers interested in program efficacy are referred to Spoth et al. (2002, 2005, 2008) who found that adolescents assigned to either prevention program condition exhibited delayed onset of alcohol use relative to control condition counterparts. Results of the current analysis also indicated that adolescents’ alcohol use increased significantly across the two outcome assessments (ß = .25; p < .001; SE = .07). With respect to the individual level main effects, results indicated that (a) both adolescents’ baseline alcohol use, ß = .47; p < .001; SE = .06, and parents’ expectations about their particular adolescents’ likelihood of drinking alcohol in the future, ß = .12; p = .007; SE = .04, significantly predicted the outcome of adolescents’ alcohol use, whereas (b) parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention did not, ß = .02; p = .73; SE = .09. Because the analysis omitted relevant background variables as a way to statistically control for prediction without influence, the relationship between parents’ expectations about their particular adolescents’ likelihood of drinking alcohol in the future and adolescents’ alcohol use includes prediction without influence and should not, therefore, be interpreted as a self-fulfilling prophecy effect. Readers interested in the self-fulfilling effects of parents’ expectations about their particular adolescents’ likelihood of drinking alcohol in the future are referred to Madon et al. (2003, 2004, 2006, 2008) and Willard et al. (2008). Finally, with respect to the interaction, the results indicated that it significantly predicted adolescents’ alcohol use following the completion of the programs, ß = −1.21; p = .005; SE = .14.1

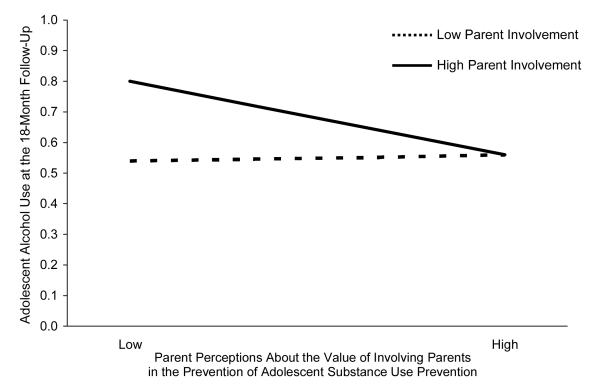

Simple effect tests

To more closely examine the pattern of the significant interaction, we performed simple effects tests. These tests separately analyzed the relation between parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention and adolescents’ alcohol use in each prevention program condition. Results showed that, among families assigned to the prevention program that systematically involved parents, parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention significantly predicted adolescents’ alcohol use in the expected direction following the completion of the programs (ß = −.23; p < .001; SE = .10). Among these families, less favorable perceptions predicted greater adolescent alcohol use across time. In contrast, among families assigned to the prevention program that did not systematically involve parents, parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention did not significantly predict adolescents’ alcohol use following the completion of the programs, ß = .02; p = .73; SE = .09. Among these families, the favorableness of parents’ perceptions did not predict changes in adolescents’ alcohol use across time. These relations, which are illustrated in Figure 1, support the hypothesis that parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention efforts had stronger self-fulfilling effects on the effectiveness of an adolescent substance use prevention program when it systematically involved parents than when it did not.2

Figure 1.

(N = 321). An illustration of relations between parents’ perceptions and adolescents’ alcohol use by prevention program condition. The dependent variable was an index reflecting the frequency of adolescents’ alcohol use at the 18-month follow-up. This index could range from 0 to 5. Parents’ perceptions predicted adolescents’ alcohol use more strongly among families assigned to an adolescent substance use prevention program that systematically involved parents than to one that did not. Low and high parents’ perceptions correspond to values that are 1/2 sd below and above the mean. Values for adolescents’ alcohol use were calculated from the multi-level model in which all variables except prevention program condition and parents’ perceptions were set at the mean. The model predicts an identical pattern at post-test, but with values decreased by .25 – the amount by which adolescents’ alcohol use increased from the post-test to the 18 month follow-up assessment, which corresponds to the coefficient for Time in Table 3.

Background control variables

To test whether the methodological approach that we used effectively accounted for prediction without influence without explicitly controlling for background variables, we performed an additional analysis. This analysis was identical to the one described above except that it also included relevant background predictors of adolescent alcohol use that were available in the questionnaires and which have been used in past research examining parents’ self-fulfilling effects on their adolescents’ alcohol use (Madon et al., 2003, 2004, 2006, 2008; Willard et al., 2008). They included family social class, parental drinking, adolescents’ gender, and adolescents’ reports of their attitudes toward alcohol use, access to alcohol, global parenting, likelihood of drinking alcohol in the future, acceptability of adolescent alcohol use, and friends’ alcohol use. Including these background variables in the analysis had virtually no effect on the association between parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention and adolescents’ alcohol use. After rounding, the coefficient corresponding to the interaction of prevention program condition × parents’ perceptions was identical to that found for the model without the background variables, ß = −1.21; p = .004; SE = .13. A similar level of correspondence emerged for the simple effects tests. Parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention significantly predicted adolescents’ alcohol use beyond the background control variables among families assigned to the prevention program that systematically involved parents, ß = −.25; p < .001; SE = .09, but not among families assigned to the one that did not, ßs = .03; p = .67; SE = .09. These findings provide evidence that the methodological approach that we used in our research obviated the need for extensive controls as a way to account for prediction without influence.

Discussion

Can perceivers’ perceptions about prevention have self-fulfilling effects on a prevention program’s effectiveness? The current research examined this question with a novel methodological approach. The approach we used was designed to enhance the internal validity of research on naturally-occurring self-fulfilling prophecies by controlling for prediction without influence in the context of an experiment that manipulated the opportunities that perceivers had to behave consistently with their naturally-occurring perceptions. We applied our approach to adolescent substance use prevention. Specifically, we assessed parents’ naturally-occurring perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention within the context of an experiment that randomly assigned families to a prevention program that either did or did not systematically involve parents in the program. We hypothesized that parents’ self-fulfilling influences would be stronger when the program systematically involved them due to the increased opportunity that parents in this condition (relative to parents in the other condition) would have to channel their behaviors in ways that could alter the program’s effectiveness. Consistent with this hypothesis, the results indicated that, among families assigned to the prevention program that systematically involved parents, parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention significantly predicted their adolescents’ alcohol up to a year after the program’s completion. In contrast, among families assigned to a prevention program that did not systematically involve parents, parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention did not predict their adolescents’ alcohol use at any point after the program’s completion.

Naturalistic Self-Fulfilling Prophecy Research

Although there are advantages to using correlational designs to study self-fulfilling prophecies, correlational findings may not necessarily reflect self-fulfilling influence. If an unmeasured background variable produced changes in both perceivers’ perceptions and the outcome, then the observed association between these variables could reflect prediction without influence, and not self-fulfilling influence (Jussim, 1991). Prediction without influence presents a serious challenge to the study of naturally-occurring self-fulfilling prophecies (Jussim, 1991). The traditional way to address this challenge is to statistically control for background variables. Although this approach can be an effective way to reduce prediction without influence, it cannot rule out prediction without influence altogether because no matter how many background control variables are included in an analytic model, it is always possible that a relevant one was omitted.

The approach we presented is unique in that it experimentally controls for prediction without influence by manipulating how much opportunity perceivers have to behave consistently with their perceptions. We applied this approach to an empirical investigation that examined whether the self-fulfilling prophecy process influenced the effectiveness of an adolescent substance use prevention program. The findings of our empirical investigation were consistent with a self-fulfilling prophecy. The association between parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention and adolescents’ alcohol use was stronger in the prevention program condition that systematically involved parents than in the one that did not. Additional analyses that included relevant background control variables of adolescent alcohol use did not meaningfully alter this pattern of findings, thereby providing evidence that our approach effectively controlled for prediction without influence without having to include extensive background variables in the analytic model.

Theoretical and Applied Implications of Findings to Self-Fulfilling Prophecy Research

A major theme within social psychology is that perception can influence reality. This emphasis dates back to the 1940s and 1950s when New Look in Perception research challenged the idea that perception is veridical by proposing that people’s perceptions are influenced by their motives, emotions, and expectations (Bruner, 1957; Merton, 1948). The self-fulfilling prophecy is central to this perspective because it involves perceptions changing reality. Our research is grounded in this tradition and reflects a particularly important application of the self-fulfilling prophecy process: Its potential to influence the effectiveness of an adolescent substance use prevention program. Consistent with the tenets of the social constructivist perspective, our results indicated that a family-focused adolescent substance use prevention program was rendered less effective in reducing adolescent alcohol use for adolescents whose parents less strongly valued the involvement of parents in adolescent substance use prevention efforts.

Because we demonstrated this effect with outcome data that spanned multiple years, our findings also speak to the long-term effects of self-fulfilling prophecies. In our data, parents’ self-fulfilling effects endured one year beyond the prevention program’s completion. This finding is particularly important because it occurred during early adolescence – a time when frequent substance use puts adolescents at significantly greater risk for a variety of negative outcomes during adulthood including alcohol dependency, sexually transmitted diseases, and criminal convictions (Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Odgers et al., 2008). Moreover, examination of the results (Figure 1) indicates that the effect we observed occurred because parents with unfavorable perceptions reduced how much their adolescents benefited from participating in the family focused prevention program. This pattern suggests that program participants may generally reap greater benefits from participating in a prevention program if the program addresses unfavorable perceptions at the outset.

Limitations

There are several limitations of our research that warrant discussion. First, our goal to examine self-fulfilling prophecies within real-world prevention efforts necessitated that the prevention programs differ from one another in terms of parents’ opportunities to influence a prevention program’s effectiveness through their program-relevant behaviors. The programs also differed from one another in terms of their theoretical approach (Botvin, 2000; Molgaard & Spoth, 2001). Though unavoidable, these differences raise an important concern: Perhaps parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention more strongly predicted adolescents’ alcohol use in the prevention program that systematically involved parents because that program was more efficacious than the program that did not systematically involve parents. Indeed, differences in program efficacy at the 18-month follow-up on the primary outcome of delayed alcohol initiation have been observed among the full sample of adolescents who participated in the Capable Families project (Spoth et al., 2002). However, among our sample, and using our outcome variable reflecting the frequency of alcohol use, the main effect of prevention program condition did not achieve significance (Table 3). This finding provides evidence that the programs did not have differential effects on the alcohol use of the adolescents in our sample. Accordingly, we believe that within these data the occurrence of a self-fulfilling prophecy (and not differences in program efficacy) is the more tenable interpretation of the findings.

A second characteristic of our research that may raise concern is the fact that our data did not reveal any evidence of prediction without influence. As reported in the results, the simple effect of parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention on adolescents’ alcohol use among these families was nearly zero, ß = .02; p = .73; SE = .09. However, it was not necessary for prediction without influence to be present in our data for our approach to work. Any rigorous test of naturally-occurring self-fulfilling prophecies must account for prediction without influence either with the traditional approach articulated by the reflection-construction model (Jussim, 1991) or with the approach we introduced. Failure to use one of these approaches in a naturalistic investigation of self-fulfilling prophecies would make it impossible to disentangle self-fulfilling influence from prediction without influence and would, therefore, constitute a fundamental flaw in the research. The extent to which prediction without influence is ultimately found to account for the relation between perceivers’ perceptions and the outcome in a data set does not change the necessity of using one of these approaches. This is because the only way to know how much effect prediction without influence had is to measure its effect. The value of using our approach, therefore, is not dependent on the degree to which prediction without influence is present in a data set, but rather on the ability of the approach to disentangle prediction without influence from a true self-fulfilling prophecy effect. This is the case even if when the actual effect of prediction without influence turns out to be zero or near zero, as it did in our data.

Third, we tested for self-fulfilling prophecy effects with respect to parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention. Our primary reason for using this perception variable was that it is directly linked to a program’s effectiveness because of its relation to parents’ program-relevant behaviors. As we discussed earlier, the more strongly parents value parental involvement in adolescent substance use prevention, the more effectively they would be expected to implement a prevention program’s content at home – behaviors that should ultimately influence the program’s overall effectiveness for their particular adolescents. Using this perception variable also had the added benefit of closely mapping onto our experimental manipulation in which parental involvement in an adolescent substance use prevention program was varied to be either relatively high or low. Nonetheless, we recognize that the perception variable we examined represents just one of many that could potentially have self-fulfilling effects on a program’s effectiveness. Other perception variables that may be particularly important to a program’s effectiveness include perceptions about a program’s efficacy and perceptions about responsiveness to treatment or prevention. We believe that examining the self-fulfilling effect of these perceptions on program effectiveness is an important area for future research to address.

Conclusion

The findings of this research indicated that parents’ perceptions about the value of involving parents in adolescent substance use prevention predicted their adolescents’ alcohol use more strongly among families assigned to a prevention program that systematically involved parents than to one that did not – an effect that endured up to one year beyond the completion of the programs. This finding indicates that parents had a self-fulfilling influence on the degree to which their adolescents benefited from participating in family focused adolescent substance use prevention program. This interpretation is consistent with existing frameworks of the self-fulfilling prophecy process (Darley & Fazio, 1980; Harris & Rosenthal, 1985; Jones, 1986; Snyder, 1984) and with a long history of theoretical perspectives within the social psychological literature that emphasize the ability of perceptions to causally alter reality and shape behavior (Bruner, 1957; Jones, 1986; Markus & Zajonc, 1985; Merton, 1948; Miller & Turnbull, 1986; Snyder, 1984). Although the self-fulfilling prophecy effects that we observed in our research were modest in magnitude, we believe they are important for at least two reasons. First, they demonstrated the utility of integrating key elements of experimental and naturalistic methods as a way to estimate perceivers’ self-fulfilling effects in the naturalistic environment, thereby maximizing the internal and external validity of such research. Second, they provided evidence that perceptions can play an important role in the effectiveness of family focused prevention efforts through the process of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the following research grants awarded to Richard Spoth: AA014702-13 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and DA 010815 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Additional analyses revealed no significant two- or three-way interactions of time with either parents’ perceptions or prevention program condition.

The model predicts an identical pattern at post-test, but with values decreased by .25 – the amount by which adolescents’ alcohol use increased from the post-test to the 18-month follow-up assessment, which corresponds to the coefficient for Time in Table 3.

Contributor Information

Stephanie Madon, Iowa State University.

Kyle C. Scherr, Central Michigan University

Richard Spoth, Iowa State University.

Max Guyll, Iowa State University.

Jennifer Willard, Kennesaw State University.

David L. Vogel, Iowa State University

References

- Alvidrez J, Weinstein RS. Early teacher perceptions and later student academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1999;91:731–746. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.91.4.731. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Berman JS. Person × situation interactions and the perception of organization climate. Dissertation Abstracts International. 1980;41(6-B):2370. 1981-72200-001. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ. Life skills training. Princeton Health Press; Princeton, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner JS. On perceptual readiness. Psychological Review. 1957;64:123–152. doi: 10.1037/h0043805. doi:10.1037/h0043805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan CM. Mothers’ generalized beliefs about adolescents: Links to expectations for a specific child. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2003;23:29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan CM, Hughes JL. Construction of social reality during early adolescence: Can expecting storm and stress increase real or perceived storm and stress. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19:261–285. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00596.x. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran WG. Sampling techniques. 3rd ed Wiley; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Darley JM, Fazio RH. Expectancy confirmation processes arising in the social interaction sequence. American Psychologist. 1980;35:867–881. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.35.10.867. [Google Scholar]

- Dew SE, Bickman L. Client expectancies about therapy. Mental health services research. 2005;7:21–33. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-1963-5. doi:10.1007/s11020-005-1963-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MJ, Rosenthal R. Mediation of interpersonal expectancy effects: 31 meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;97:363–386. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.97.3.363. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard KI, Orlinsky DE, Perilstein J. Contribution of therapists to patients’ experiences in psychotherapy: A components of variance model for analyzing process data. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1976;44:520–526. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.44.4.520. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.44.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. Academic Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Jones EE. Interpreting interpersonal behavior: The effects of expectancies. Science. 1986 Oct 6;234:41–46. doi: 10.1126/science.234.4772.41. doi:10.1126/science.234.4772.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L. Teacher expectations: Self-fulfilling prophecies, perceptual biases, and accuracy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:469–480. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.3.469. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L. Social perception and social reality: A reflection-construction model. Psychological Review. 1991;98:54–73. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.1.54. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L, Eccles JS. Teacher expectations II: Construction and reflection of student achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:947–961. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.63.6.947. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L, Eccles J. Naturally occurring interpersonal expectancies. Review of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;15:74–108. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L, Eccles JS, Madon S. Social perception, social stereotypes, and teacher expectations: Accuracy and the quest for the powerful self-fulfilling prophecy. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 28. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1996. pp. 281–388. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60240-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L, Harber KD. Teacher expectations and self-fulfilling prophecies: Knowns and unknowns, resolved and unresolved controversies. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2005;9:131–155. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0902_3. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0902_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft I, de Leeuw J. Introducing multilevel modeling (Introducing Statistical Methods series) Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer KL, Molgaard V, Spoth R. The Strengthening Families Program for the prevention of delinquency and drug use. In: Peters RD, McMahon RJ, editors. Preventing childhood disorders, substance abuse, and delinquency. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1996. pp. 241–267. [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS system for mixed models. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Guyll M, Buller AA, Scherr KC, Willard J, Spoth R. The mediation of mothers’ self-fulfilling effects on their children’s alcohol use: Self-verification, informational conformity, and modeling processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:369–384. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.2.369. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.95.2.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Guyll M, Spoth RL, Cross SE, Hilbert SJ. The self-fulfilling influence of mother expectations on children’s underage drinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1188–1205. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1188. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Guyll M, Spoth R, Willard J. Self-fulfilling prophecies: The synergistic accumulation of parents’ beliefs on children’s drinking behavior. Psychological Science. 2004;15:837–845. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00764.x. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Smith A, Jussim L, Russell DW, Eccles JS, Palumbo P, Walkiewicz M. Am I as you see me or do you see me as I am? Self-fulfilling prophecies and self-verification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1214–1224. doi:10.1177/0146167201279013. [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Willard J, Guyll M, Trudeau L, Spoth R. Self-fulfilling prophecy effects on mothers’ beliefs on children’s alcohol use: Accumulation, dissipation, and stability over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:911–926. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.6.911. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.6.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H, Zajonc RB. The cognitive perspective in social psychology. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 3rd ed Vol. 1. Random House; New York: 1985. pp. 137–230. [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. The self-fulfilling prophecy. Antioch Review. 1948;8:193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT, Turnbull W. Expectancies and interpersonal processes. In: Rosenzweig MR, Porter LW, editors. Annual Review of Psychology. Vol. 37. Annual Reviews; Stanford, CA: 1986. pp. 233–256. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.37.020186.001313. [Google Scholar]

- Molgaard VM, Kumpfer K, Fleming E. Strengthening families program for parents and youth 10-14: A video-based curriculum. Institute for Social and Behavioral Research; Ames, IA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Molgaard V, Spoth R. Strengthening Families Program for young adolescents: Overview and outcomes. In: Pfeiffer SI, Reddy LA, editors. Innovative mental health programs for children: Programs that work. Co-published simultaneously as Residential treatment for children & youth. No. 3. Vol. 18. Haworth Press; Binghamton, NY: 2001. pp. 15–29.pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Molgaard V, Spoth R, Redmond C. Competency training: The Strengthening Families Program for Parents and Youth 10-14 (OJJDP Juvenile Justice Bulletin NCJ 182208) U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Caspi A, Nagin DS, Piquero AR, Slutski WS, Milne BJ, Dickson N, Poulton R, Moffit TE. Is it important to prevent early exposure to drugs and alcohol among adolescents? Psychological Science. 2008;19:1037–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02196.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olver IN, Taylor AE, Whitford HS. Relationships between patients’ pre-treatment expectations of toxicities and post chemotherapy experiences. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14:25–33. doi: 10.1002/pon.804. doi:10.1002/pon.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz EM, Dong W. Effects of mothers’ perceptions of children’s competence: The moderating role of mothers’ theories of competence. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:950–961. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.950. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr KC, Madon S, Guyll M, Willard J, Spoth R. Self-verification as a mediator of mothers’ self-fulfilling effects on adolescents’ educational attainment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2011;37:587–600. doi: 10.1177/0146167211399777. doi:10.1177/0146167211399777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AE, Jussim L, Eccles J. Do self-fulfilling prophecies accumulate, dissipate, or remain stable over time? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:548–565. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.3.548. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.3.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder M. When belief creates reality. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental psychology. Vol. 18. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1984. pp. 247–305. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder M. Motivational foundations of behavioral confirmation. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 25. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1992. pp. 67–114. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60282-8. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder M, Stukas AA. Interpersonal processes: The interplay of cognitive, motivational, and behavioral activities in social interaction. Annual Review. 1999;50:273–303. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.273. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Randall KG, Shin C, Redmond C. Randomized study of combined universal family and school preventative interventions: Patterns of long-term effects on initiation, regular use, and weekly drunkenness. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:372–381. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.372. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Randall KG, Trudeau L, Shin C, Redmond C. Substance use outcomes 5 1/2 years past baseline for partnership-based, family-school preventive interventions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.023. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C. Randomized trial of brief family interventions for general populations: Adolescent substance use outcomes 4 years following baseline. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:627–642. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.4.627. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, Trudeau L, Shin C. Longitudinal substance initiation outcomes for a universal preventive intervention combining family and school programs. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:129–134. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.16.2.129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouilloud DO, Sarrazin PG, Martinek TJ, Guillet E. The influence of teacher expectations on student achievement in physical education classes: Pygmalion revisited. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2002;32:591–607. doi:10.1002/ejsp.109. [Google Scholar]

- Trouilloud D, Sarrazin P, Bressoux P, Bois J. Relation between teachers’ early expectations and students’ later perceived competence in physical education classes: Autonomy-supportive climate as a moderator. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98:75–86. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.75. [Google Scholar]

- Willard J, Madon S, Guyll M, Spoth R, Jussim L. Self-efficacy as a moderator of positive and negative self-fulfilling prophecy effects: Mothers’ beliefs and children’s alcohol use. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;38:499–520. doi:10.1002/ejsp.429. [Google Scholar]