Abstract

Appropriate prescribing remains an important priority in all medical areas of practice.

Objective

The objective of this study was to apply a Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) to identify issues of inappropriate prescribing amongst patients admitted from the Emergency Department (ED).

Methods

This study was carried out at Malta's general hospital on 125 patients following a two-week pilot period on 10 patients. Patients aged 18 years and over and on medication therapy were included. Medication treatment for inappropriateness was assessed by using the MAI. Under-prescribing was also screened for.

Results

Treatment charts of 125 patients, including 697 medications, were assessed using a MAI. Overall, 115 (92%) patients had one or more medications with one or more MAI criteria rated as inappropriate, giving a total of 384 (55.1%) medications prescribed inappropriately. The mean SD MAI score per drug was 1.78 (SD=2.19). The most common medication classes with appropriateness problems were biguanides (100%), anti-arrhythmics (100%) and anti-platelets (96.8%). The most common problems involved incorrect directions (26%) and incorrect dosages (18.5%). There were 36 omitted medications with untreated indications.

Conclusions

There is considerable inappropriate prescribing which could have significant negative effects regarding patient care.

Keywords: Inappropriate Prescribing; Pharmaceutical Services; Emergency Service, Hospital; Malta

Introduction

The pharmacist's role has evolved over time, moving from traditional medication dispensing to involvement in direct patient care to the delivery of pharmaceutical care with a focus on enhancing medication appropriateness and preventing drug-related problems. Medication appropriateness combines different elements of evidence-based medicine with professional opinion when there is incomplete evidence.1 Clinical pharmacists optimise medication use and improve patient's care when working as part of a multidisciplinary team in different settings, including hospital wards2,3, intensive care units4, and community-based physician group practices.5 A model for the provision of clinical pharmacy services has shown that understaffing of clinical pharmacists is likely in hospitals if all core clinical services were to be provided.6 Moreover, the literature is limited in reporting studies regarding models of practice that involve clinical pharmacists assigned exclusively to the emergency department (ED).

The ED in general acute teaching hospitals is a busy environment where provision of optimal care is a challenge. It has been shown that in the ED patients are at risk of receiving suboptimal medication compared to that provided in inpatient and ambulatory care settings.7 Identifying and characterising inappropriate prescribing at the ED would show the need for clinical pharmacy services in this setting and could be the next step for developing a robust model of practice specifically for the ED. Therefore, the aim of this study was to apply the Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI)8 by a clinical pharmacist to identify issues of inappropriate prescribing amongst patients admitted from the ED.

Methods

The study was conducted over a two month period between November and December of 2005, in Malta at St Luke's Hospital, a large acute general teaching hospital with 12,000 patient admissions per year. All patients aged 18 years and over, taking one or more medicines, who presented at the ED during the 2 month study period and who were forwarded to the care of any one of two participating consultant physicians were included in this study. The two month time frame was chosen as this was thought to be the reasonable time period which would provide a meaningful sample size. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee and confidentiality of the subjects was maintained. This study involved a cluster sample in a non-randomized uncontrolled prospective study. A pragmatic convenience cluster sampling method of patients admitted under two specific consultants was chosen because the principal investigator was the clinical pharmacist attached to each of the admitting consultant physician teams. As such, this approach offered 'real life' characterisation of an existing model of practice. Patients who did not pass through the ED but were directly admitted to wards were excluded. These patients were not recruited because they would have been re-assessed by other doctors apart from the ED physician and would have confounded the results.

A total of 125 patients were recruited. Taking a level of confidence of 95% and an error of 10 (that is SD=5), the sample population was estimated to be that of 92 patients. The sample proportion, that is the number of patients having inappropriate prescriptions, to calculate the sample population was taken as 0.603. This sample proportion was estimated from previous studies which used the MAI.9,10 Inappropriate prescribing in these studies ranged from 46.1% to 74.5%. Therefore, a mean of 60.3% (sample proportion) was used. An error of 10 was used (±5) due to the fact that the difference in inappropriate prescribing in other studies was large. Therefore, to obtain a more accurate result 125 patients were included in this study.

Following medical assessment and intervention at ED, drug treatment charts and medical files containing case notes of study participants were reviewed by the principal investigator before the admitting consultant physician reviewed the patients. Treatment review of both acute and chronic medications a patient was on took place prior to the post-take ward round to ensure that any inappropriateness of medication detected did not arise due to an intervention by a doctor on the ward. Prescribing of acute medications and changes (or the lack of) in chronic drug treatment made by doctors at the ED were considered; as drug treatment after the patient was seen at the ED was reviewed for inappropriate prescribing. Each drug on the treatment chart was assessed to determine whether it is appropriate or not. Appropriateness of medication for each drug a patient was on was evaluated by using the MAI.8

The MAI is designed to allow rating of ten explicit criteria to determine whether a given medication is appropriate for an individual. The ten criteria of the MAI, worded as questions, pertain to the individual patient and drug in question (Table 1). These criteria are: an indication for the drug, drug effectiveness for the patient's condition, correct dosage and directions, practical directions, drug-drug interaction, drug-disease interaction, unnecessary duplication with other drugs, duration of therapy and cost-effectiveness.8 Each criterion for the appropriateness of prescribing is rated on a three-point Likert scale, depending on whether the drug is appropriate, marginally appropriate or not appropriate. If additional information is required to answer a question "option Z", which means "Do not know", can be selected.

Table 1.

Medication Appropriateness Index8

| Question | Score(a) |

|---|---|

| 1. Is there an indication for the drug? | 3 |

| 2. Is the medication effective for the condition? | 3 |

| 3. Is the dosage correct? | 2 |

| 4. Are the directions correct? | 2 |

| 5. Are the directions practical? | 2 |

| 6. Are there clinically significant drug-drug interactions? | 2 |

| 7. Are there clinically significant drug-disease/condition interactions? | 1 |

| 8. Is there unnecessary duplication with other drug(s)? | 1 |

| 9. Is the duration of therapy acceptable? | 1 |

| 10. Is this drug the least expensive alternative compared with others of equal utility? | 1 |

| Maximal score of inappropriateness | 18 |

| aA weight of three is given for indication and effectiveness. A weight of two is assigned to dosage, correct directions, practical directions and drug-drug interactions. A weight of one is assigned to drug-disease interactions, expense, duplication and duration.9 These results in a total combined score of 0 to 18 (0 meaning the drug is appropriate and 18 representing maximal inappropriateness). | |

If a drug is 'Appropriate' or ‘Marginally appropriate’ a score of zero is given to that drug. Each of the 10 criteria of the MAI that is considered ‘Not appropriate’ is given a maximum score of 1, 2 or 3 for each drug (Table 1). A weight of three is given for indication and effectiveness. A weight of two is assigned to dosage, correct directions, practical directions and drug-drug interactions. A weight of one is assigned to drug-disease interactions, expense, duplication and duration.9 This therefore results in a total combined score of 0 to 18 (0 meaning the drug is appropriate and 18 representing maximal inappropriateness). Combining the total MAI scores for each prescribed drug will yield a score for each patient. The total score per patient will depend on the number of drugs a patient is on. For example, if a patient is on one drug the minimum score would be 0 and the maximum score is 18; whilst if the patient is on 2 drugs the minimum score per patient is 0 with a maximum score of inappropriateness of 36.

To assess the reliability of the MAI intra-observer agreements were tested. The principal investigator used the MAI to collect data on 10 patients and then the MAI was re-used on the treatment chart of the same 10 patients by the principal investigator to collect the same data a month later. The tool resulted to be reliable since there was no difference in the data collected. Also, this ensured consistency in data collection by the principal investigator, who was the one who carried out the treatment chart review. A pilot study using the MAI was carried out by the principal investigator on 8% of the sample population being studied, i.e. 10 patients. The pilot study confirmed that no changes to the tool were required.

The MAI does not detect omitted drugs, whereby a patient is suffering from a condition but he/she is not receiving drug treatment for it. For the purpose of the study, the number of documented conditions which were not treated according to international guidelines and for which there was no documented contra-indications for a medication were also recorded. These were divided into chronic conditions or acute conditions, depending whether they required long-term medication treatment or acute short courses of medications to be managed.

All scores resulting from the MAI were inputted in the Statistical Packages of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 12 database which was constructed for data entry and analysis and this was password protected. This study used quantitative, including counts, percentages, mean (standard deviation), median and ranges, to yield frequencies. Cronbach's Alpha, which is a measure of internal consistency, was used to assess reliability of the MAI. Cronbach's Alpha values vary from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1.0 indicating greater reliability. Values above 0.80 are preferable as indicators of internal consisteny of a tool, although values above 0.70 are acceptable.11 Other studies assessing the use of the MAI used descriptive statistics as well, to analyse their data.9,10,12

Results

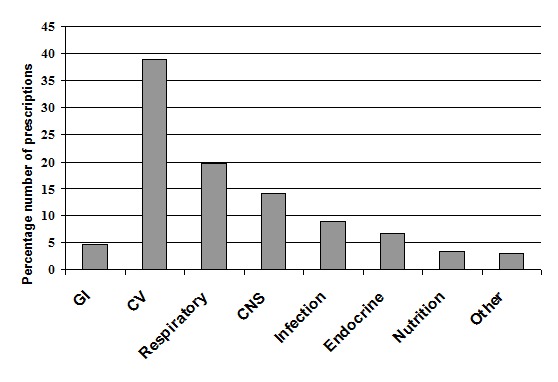

Cronbach's Alpha was higher than 0.889 for all criteria of the MAI, as illustrated in Table 2. The participant characteristics are presented in Table 3. The treatment charts of 125 patients were reviewed. Each patient was having one or more medicines and some of these medicines were prescribed in more than one patient. The 125 patients had a total of 697 drugs and each of these drugs were reviewed and assessed for appropriateness. Based on British National Formulary (BNF)13 drug categories, cardiovascular medications were the most commonly prescribed (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Cronbach's Alpha for the ten criteria per MAI

| Question | Cronbach's Alpha |

|---|---|

| 1. Drug indication | 1.000 |

| 2. Effectiveness | 1.000 |

| 3. Correct dosage | 1.000 |

| 4. Correct directions | 1.000 |

| 5. Practical directions | 1.000 |

| 6. Drug-drug interaction | 0.889 |

| 7. Drug-disease/condition interactions | 1.000 |

| 8. Duplication | 1.000 |

| 9. Duration of therapy | 0.978 |

| 10. Expense | 1.000 |

| Total score | 1.000 |

Table 3.

Summary of patients' characteristics

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| TOTAL | 125 |

| Men | 71 (57%) |

| Mean age in years (± SD) | 67.46 SD=16.96 |

| Age range | 19-95 |

| Total no of different medical conditions | 35 |

| Range of medical conditions per patient | 1-7 |

| Total number of drugs | 697 |

| Mean no. of drugs per patient | 7.09 SD=2.74 |

| Median no. of drugs | 7 |

| Range of drugs | 1-13 |

| Medicines for chronic conditions | 105 |

| Medicines for acute conditions | 17 |

Figure 1.

BNF13 Drug categories mostly prescribed (n = 697)

A total of 313 drugs (44.9%) were considered to be appropriate out of which 56 drugs were marginally appropriate, whilst 55.1% (n=384) of drugs were prescribed inappropriately, i.e. 55.1% of drugs met one or more criteria of the MAI. Overall, 92% of the study population were prescribed one or more drugs inappropriately. Table 4 displays the total inappropriate prescriptions for each criterion of the MAI. The mean MAI score per drug was 1.78 SD=2.19 and the mean MAI score per patient was 9.90 SD=7.48 (Table 5). The score of inappropriate prescribing per patient in this study can range from 0 to 234 since the maximum number of drugs encountered per patient was 13 and the maximum score for inappropriateness for each drug is 18.

Table 4.

Total inappropriate prescriptions for each criterion of the MAI

| Question | Drugs with an inappropriate MAI criterion (n=697) | Patients with an inappropriate prescription (n=125) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | & | |

| 1. Drug indication | 52 | 7.5 | 36 | 28.8 |

| 2. Effectiveness | 17 | 2.4 | 15 | 12.0 |

| 3. Correct dosage | 129 | 18.5 | 78 | 62.4 |

| 4. Correct directions | 181 | 26.0 | 91 | 72.8 |

| 5. Practical directions | 60 | 8.6 | 42 | 33.6 |

| 6. Drug-drug interaction | 37 | 5.3 | 28 | 22.4 |

| 7. Drug-disease/condition interactions | 23 | 3.3 | 19 | 15.2 |

| 8. Duplication | 16 | 2.3 | 15 | 12.0 |

| 9. Duration of therapy | 104 | 14.9 | 64 | 51.2 |

| 10. Expense | 77 | 11.0 | 52 | 41.6 |

Table 5.

MAI Score of inappropriate prescribing per drug and per patient

| Statistics | Score per drug | Score per patient |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.78 SD= 2.19 | 9.90 SD=7.48 |

| Median | 1.00 | 9.00 |

| Range | 0-12 | 0-30 |

| Possible range | 0-18 | 0-234 |

| Males | 1.64 | 8.9 |

| Females | 1.94 | 10.9 |

Biguanides (metformin), anti-arrhythmics (amiodarone), anti-platelets, antibiotics and steroids (inhaled and systemic) were the most inappropriately prescribed classes of drugs as they did not fulfil one or more of the MAI criteria, as indicated in Table 6. Directions were always omitted in metformin prescriptions and there were three instances when metformin was also prescribed in the wrong dose. Prescriptions for amiodarone were considered inappropriate due to inefficacy or incorrect dosages. Prescriptions for anti-platelets (aspirin and dipyridamole) were considered inappropriate mainly due to lack of directions. All of the prescriptions for antibiotics (except two) did not specify the duration of therapy and therefore were considered inappropriate. Apart from inappropriate duration, prescriptions for antibiotics were also considered as inappropriate since some of them did not fulfill one or more of the MAI criteria. Directions for administration of intravenuos hydrocortisone were omitted from all of the prescriptions.

Table 6.

Most inappropriately prescribed classes of drugs

| Class of drug | Total prescriptions |

Inappropriate prescriptions n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Biguanides | 12 | 12 (100.0) |

| Anti-arrhythmics | 10 | 10 (100.0) |

| Anti-platelets | 63 | 61 (96.8) |

| Antibiotics | 57 | 55 (96.5) |

| Steroids | 44 | 40 (90.9) |

| Benzodiazepines | 12 | 10 (83.3) |

| Insulin | 18 | 15 (83.3) |

Thirty-six medical conditions, corresponding to 36 omitted drugs, were encountered where a patient was suffering from a condition but was not receiving medications to manage the condition. These 36 untreated indications were found in 32 patients (25.6% of the study population). The most common medications which were omitted in chronic medical conditions were an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor in patients suffering from congestive heart failure (6 times), an anti-hypertensive medication in patients suffering from hypertension (4 times) and a beta-blocker in patients suffering from ischaemic heart disease (4 times). The only medication encountered which was omitted in an acute condition was paracetamol to manage patients with pyrexia (8 times).

Discussion

The MAI was originally designed for older patients.9 However, the MAI can be considered to be a reliable tool even in other age groups since results of the reliability studies did not show any statistical difference. Hanlon et al.12 used the MAI amongst elderly inpatients and physician-pharmacist pair's consensus rating for the 10 criteria of the MAI were used to measure inappropriate prescribing. Barber et al.14 tried to establish whether judgements of appropriateness that included patients' perspectives and contextual factors could lead to different conclusions when using instruments such as the MAI. The design differed from the current study as, apart from using the MAI, interviews were carried out with patients and doctors. Similar to the current study, Schmader et al.15 employed a clinical pharmacist to assess prescribing appropriateness with the help of the MAI, however the study was carried out in an out-patient setting. No studies were identified which used the MAI in the ED.

The results of this study show that 55.1% of the drugs prescribed during this study, based on MAI criteria8, were inappropriate for one reason or another. Inappropriate use of medication amongst patients is a common problem that often leads to increased risk of adverse drug events, healthcare utilisation, mortality and morbidity.16 In another study where the MAI was applied in an in-patient setting, the rate of inappropriate prescriptions was 78.3%12, however the study design was different. Inappropriate prescriptions in primary healthcare studies ranged from 39.5%17 to 46.1%.10 Overall, 92% of the study population had one or more medications with one or more of the MAI criteria rated as inappropriate. This finding is consistent with other studies that used the MAI where between 91.9% to 94.3% of the patients were taking inappropriate drugs.10,12,17 Inadequate prescribing practice has been attributed to the difficulty prescribers had to understand clinical pharmacology and therapeutics.18 Such shortcomings may also be magnified by complex and poorly designed systems, poor teamwork and psychological and environmental stressors.19 This is of concern as inappropriate prescribing increases the likelihood of experiencing at least one adverse health outcome more than twofold20 and can also increase hospitalisations.21

The major category of inappropriate prescribing encountered was incorrect or omitted directions for use, resulting in 26% of all prescriptions (Table 4). This occurred commonly with administration of drugs in relation to meals (example aspirin) and with the rate at which intravenous drugs should be administered. One may argue that ED doctors may give appropriate directions verbally to other health care professionals and patients. Whilst this is not incorrect, patients and ward staff should be given written instructions on the proper administration of drugs. This study also found that 8.6% of the prescriptions had impractical directions (Table 4). This is a low rate when compared to the study by Hanlon et al. which found impractical directions in up to 55.2% of prescriptions.12

In this present study, incorrect dosages were the second most commonly encountered types of inappropriateness amongst prescriptions, with 18.5% wrong dosages, when compared to those observed in other studies which varied between 6.7%14 to 11.48% in the study by Hanlon et al.12 to 17.3% reported by Schmader et al.22 Hanlon et al.12 reported a lower number (50.9%) of patients with an inappropriate dosage when compared to the present study (62.4%). A retrospective study by Phillips et al. 23 concluded that incorrect dosing was the most common type of medication error resulting in patient death (40.9%).Prescriptions where no dosage was specified in this study were considered as inappropriate.

Data from this study indicates that whilst inappropriate prescribing was encountered with 55.1% of the drugs in this study, the extent of inappropriateness was a minimal one as the mean MAI score of inappropriate prescribing per drug was 1.78 SD=2.19. Also, one could argue whether the ED is the right place for thorough medication review. Whilst serious drug related problems should be treated, it may be more convenient to recommend certain changes in drug therapy to the general practitioner or to the treating physician of the hospital ward after transfer from the ED. However, these results should not encourage complacency since inappropriate medication use does increase adverse health outcomes.20 Moreover, studies have shown that pharmacists can significantly improve score of inappropriate prescribing.10,24

The therapeutic classes involved in inappropriate prescribing differed from one study to another.12,20,22 These observations may have important implications with regards to the need for improving prescribing practices by the implementation of protocols and hospital guidelines that could result in cost savings and less adverse effects. It is also pertinent to address the importance of an untreated indication even though this is not one of the MAI criteria. It is of concern that 25.6% of the study population did not receive a drug to manage their condition. Twenty-eight out of the 36 omitted drugs were to manage chronic conditions. Acute issues at hand can potentially mask some of the chronic issues that patients may also have. These findings suggest that doctors at the ED devote considerable time to the acute problem and prescribing for chronic diseases is overlooked, as confirmed by other studies.25

The following limitations of the study need to be highlighted. The MAI was applied by one clinical pharmacist to detect inappropriate prescriptions. Secondly, while broadly applicable and easy to use, the MAI does not address some important medication use issues, including the causality of adverse drug reactions and patient adherence. In addition the MAI depends predominantly on pharmacological criteria, and so does not represent cases that would be considered appropriate when including the patient’s views and associated factors. Since the study was carried out over a two month period this does not account for seasonal variation. Also, the current study did not link the MAI scores with patient outcomes. Finally, since the principal investigator had limited the study to patients admitted under the care of two consultant physicians, these results cannot be extrapolated to other settings. However, they lend support to the use of the MAI as an aid to the clinical pharmacists in identifying medication inappropriateness in the ED setting.

Conclusions

Suboptimal care is present as evidenced by the vast range of inappropriate prescribing encountered in this study. The data presented herein reiterate the importance of a clinical pharmacist practising at the ED. The inclusion of pharmacists as part of a multidisciplinary team can assist in appropriate prescribing, as well as in the implementation of standard operating procedures and evidence-based guidelines to be used in the ED, amongst other tasks. Notwithstanding the limitations, the MAI can aid clinical pharmacists identify medication inappropriateness even in the ED setting.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None

Contributor Information

Lorna Marie West, Mater Dei Hospital. Tal-Qroqq (Malta)..

Maria Cordina, Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, University of Malta. Msida (Malta)..

Scott Cunningham, Robert Gordon University. Aberdeen (United Kingdom)..

References

- 1.Buetow SA, Sibbald B, Cantrill JA. Appropriateness in health care: application to prescribing. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:261–271. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartzberg E, Rubinovich S, Hassin D, Haspel J, Ben-Moshe A, Oren M, Shani S. Developing and implementing a model for changing physicians’ prescribing habits – the role of clinical pharmacy in leading the change. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2006;31:179–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2006.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weant KA, Armitstead JA, Ladha AM, Sasaki-Adams D, Hadar EJ, Ewend MG. Cost effectiveness of a clinical pharmacist on a neurosurgical team. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:946–950. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000347090.22818.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacLaren R, Bond CA. Effects of pharmacist participation in intensive care units on clinical and economic outcomes of critically ill patients with thromboembolic or infarction-related events. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:761–768. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.7.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devine EB, Hoang S, Fisk AW, Wilson-Norton JL, Lawless NM, Louie C. Strategies to optimize medication use in the physician group practice: The role of the clinical pharmacist. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49:181–191. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.08009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bond CA, Raehl CL, Patry R. Evidence-based core clinical pharmacy services in United States hospitals in 2020: services and staffing. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:427–440. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.5.427.33358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cobaugh D, Schneider S. Medication use in the emergency department: Why are we placing patients at risk? Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:1832–1833. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanlon J, Schmader K, Samsa G, Weinberger M, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, Cohen HJ, Feussner JR. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1045–1051. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90144-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samsa GP, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Weinberger M, Clipp EC, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, Landsman PB, Cohen HJ. A summated score for the medication appropriateness index: development and assessment of clinimetric properties including content validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:891–896. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chrischilles EA, Carter BL, Lund BC, Rubenstein LM, Chen-Hardee SS, Voelker MD, Park TR, Kuehl AK. Evaluation of the Iowa Medicaid Pharmaceutical case management program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2004;44:337–349. doi: 10.1331/154434504323063977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pallant J. SPSS survival manual: a step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS. 4th edition. England: Open University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanlon JT, Artz MB, Pieper CF, Linblad CI, Sloane RJ, Ruby CM, Schmader KE. Inappropriate medication use among frail elderly inpatients. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:9–14. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.British Medical Association and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. British National Formulary. Number 49. Great Britain: The Pharmaceutical Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barber N, Bradley C, Barry C, Stevenson F, Britten N, Jenkins L. Measuring the appropriateness of prescribing in primary care: are current measures complete? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005;30:533–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2005.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmader KE, Hanlon JT, Landsman PB, Samsa GP, Lewis IK, Weinberger M. Inappropriate prescribing and health outcomes in elderly veterans outpatients. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31:529–533. doi: 10.1177/106002809703100501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton JH, Gallagher PF, O'Mahony D. Inappropriate prescribing and adverse drug events in older people. BMC Geriatr. 2009;9:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bregnhoj L, Thirstrup S, Kristensen MB, Bierrum L, Sonne J. Prevalence of inappropriate prescribing in primary care. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29:109–115. doi: 10.1007/s11096-007-9108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson PR, Yeo WW, Bax NDS, Ramsay LE. Essentials of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics – 1. Prescribing. Student BMJ. 1995;3:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, McKenna KJ, Clapp MD, Federico F, Goldmann DA. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA. 2001;285:2114–2120. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perri M, Menon AM, Deshpande AD, Shinde SB, Jiang R, Cooper JW, Cook L, Griffin SC, Lorys A. Adverse Outcomes Associated with Inappropriate Drug Use in Nursing Homes. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:405–411. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindley C, Tully M, Paramsothy V, Tallis RC. Inappropriate medication is a major cause of adverse drug reactions in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 1992;21:294–300. doi: 10.1093/ageing/21.4.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmader K, Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, Landsman PB, Samsa GP, Lewis I, Uttech K, Cohen HJ, Feussner JR. Appropriateness of medication prescribing in ambulatory elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:1241–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips J, Beam S, Brinker A. Retrospective analysis of mortalities associated with medication errors. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58:2130. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/58.19.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stuijt CC, Franssen EJ, Egberts AC, Hudson SA. Appropriateness of prescribing among elderly patients in a Dutch residential home: observational study of outcomes after a pharmacist-led medication review. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:947–954. doi: 10.2165/0002512-200825110-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spinewine A, Swine C, Dhillon S, Franklin BD, Tulkens PM, Wilmotte L, Lorant V. Appropriateness of use of medicines in elderly inpatients: qualitative study. BMJ. 2005;331:935–939. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38551.410012.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]