Abstract

Awareness of the impact of disasters globally on mental health is increasing. Known difficulties in preparing communities for disasters and a lack of focus on relationship building and organizational capacity in preparedness and response have led to a greater policy focus on community resiliency as a key public health approach to disaster response. This perspective emphasizes relationships, trust and engagement as core competencies for disaster preparedness and response/recovery. In this paper, we describe how an approach to community engagement for improving mental health services, disaster recovery, and preparedness from a community resiliency perspective emerged from our work in applying a partnered, participatory research framework, iteratively, in Los Angeles County and the City of New Orleans. Our approach has a specific focus on behavioral health and relationship building across diverse sectors and stakeholders concerned with under-resourced communities. We use as examples both research studies and services demonstrations discuss the lessons learned and implications for providers, communities, and policymakers pertaining to both improving mental health outcomes and addressing disaster preparedness and response.

Keywords: Disasters, Disaster response, Community engagement, Community health, Behavioral health

Background

Recent disasters such as Katrina/Gulf storms, the September 11 terrorist attacks and Superstorm Sandy have increased awareness among policy makers, providers, and the public concerning long-term health risks, including psychological distress, from disaster exposure and the key role that first responders-- nurses, other medical and emergency response staff and volunteers—play in mitigating risks early by helping to assure safety, services linkage, and support for physical, mental and social well-being. Large scale disasters disrupt physical, social and communication infrastructures and diminish coping resources and social supports1-3 and pose both temporary and long-term threats to physical and psychological health.4, 5 One of the key barriers to recovery among vulnerable populations is high risk of mental distress and disorders5, 6 that interfere with effective help-seeking and timely evacuation and increase risk for other long-term health outcomes.7, 8 A subset of affected people develop new disorders and chronic illness and impairment.9-11 Public health threats such as infectious disease outbreaks and radiation exposure also threaten health security and create often disproportionate distress in vulnerable groups in under-resourced communities.12-14

All persons exposed to disasters are vulnerable, but subgroups including children10 and under-resourced ethnic minority communities12-14 are at high risk for poor outcomes. Under-resourced communities such as urban communities of color are at higher risk for poorer health outcomes owing to pre-existing disparities in health, access to services and environmental risk factors.1, 15, 16 They also face disparities in disaster response time and outcomes.17, 18 Disasters generate multiple stressors that can trigger ongoing psychological distress in such vulnerable groups19, as observed post-Katrina.7, 20, 21 Given that disasters are unexpected and local resources are often overwhelmed, response is facilitated by first responders from government agencies and volunteer responders from community-based agencies including Volunteer Organizations Active in Disasters (VOAD). First responders also include nurses and other medical staff from public health and medical clinics and hospitals, emergency response agencies, schools, and volunteers of agencies such as faith-based groups and neighborhood associations. Responders have diverse roles in preparedness (outreach, training), response (assessment, services, referral) and recovery (services rebuilding and coordination). All first responders are also at high risk for psychological distress and unmet need.22

To address the broader social and environmental factors that may affect outcomes of disaster preparedness, response, and longer-term recovery efforts, Community Disaster Resilience has emerged as recent national policy priority.23, 24 CDR follows a community-systems model10, 25 that emphasizes communication, partnership and activating networks around disaster-response goals, and community engagement26, 27 and improved provider communication with underserved populations.28, 29 However, there has been no operational definition of CDR or model demonstration of how best to apply these principles in practice in vulnerable communities. Building capacity for CDR requires an approach suitable to integrating and coordinating the perspectives and skills of diverse stakeholders, including historically vulnerable groups, first responders, and experts in evidence-based approaches to improving outcomes, including for mental health consequences of disasters. Because Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) is recommended for both program development and research with vulnerable groups30-38 it offers one approach to develop and operationalize CDR.

Community-Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR)39, 40 is a manualized form of CBPR that is suitable for this purpose as it promotes equal power and authority of diverse community and academic partners to develop and evaluate programs while building scientific and community capacity for using findings and products.41 CPPR promotes two-way knowledge exchange across diverse stakeholders through a community engagement paradigm. We use the term community to refer to persons who work, share recreation or live in a given area. Community engagement refers to values, strategies and actions that support authentic partnerships, including mutual respect and inclusive participation, power sharing and equity, and flexibility in goals, methods, and timeframes to fit priorities and capacities of communities.30, 41 The CPPR approach is asset-based and designed to build community capacity while developing knowledge for scientific and community benefit. A key strategy is identifying the “win-win” or fit of goals across stakeholders. A CPPR initiative involves forming a partnered Council, identifying experts to support the work and community forums for broad input.42 CPPR unfolds in 3 stages: Vision (planning), Valley (work) and Victory (products, dissemination) and supports evaluation within a participatory approach.31, 36, 42

Over the past 10 years, we have developed this framework and approach to applying CPPR to address mental health outcome disparities in under-resourced communities of color in Los Angeles and mental health recovery post-disaster in New Orleans. Our work across these two areas has evolved in stages enabling us to apply lessons learned across projects and share resources across communities iteratively. The signature projects for the evolution of our approach are Witness for Wellness/Community Partners in Care (CPIC) in Los Angeles,42, 43 the REACH NOLA Mental Health Infrastructure and Training (MHIT) Program for post-Katrina disaster recovery 44 in New Orleans and the Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience (LACCDR) initiative. All projects were supported in part by the Partnered Research Center (PRC) for Quality Care, which aims to conduct research following a CPPR approach to improve mental health outcomes.45 Overall, the Center follows a learning community model to promote community engaged approaches to address mental health disparities and to develop a community resilience approach to disaster preparedness and response.

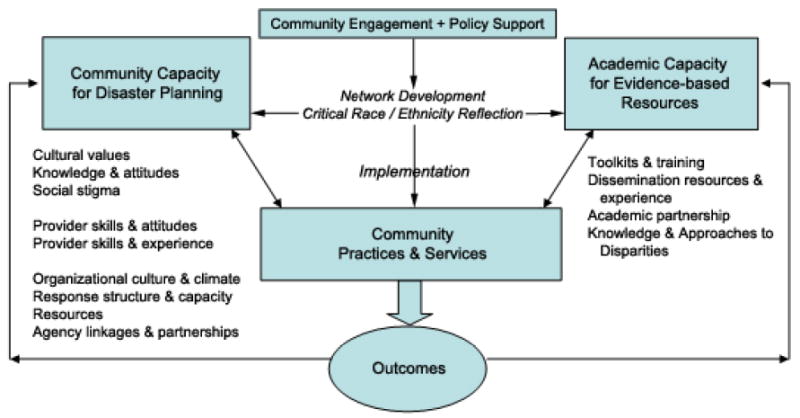

Figure 1 provides a conceptual model for the community engagement approach to disaster response, including for mental health that has emerged from our “tale of two cities.”

Figure 1.

Framework for Community Engagement in Disaster Response

In the framework, community engagement promoting equal decision making through two-way knowledge exchange is combined with policy support to promote network development and integration of community and academic/clinical and public health perspectives, in order to generate programs that are implemented and evaluated to build community disaster resilience or improve mental health outcomes. A key component of the development of networks, policy, and implementation however is attention to the salience of race and ethnicity, a process of leadership reflection emerging from critical race theory.46, 47 This helps assure that programs developed and their implementation will be equitable from a social justice perspective. The program implementation in services lead to outcomes which are also determined in partnership; and the results of the evaluation are used in a feedback loop to build community and academic capacity and inform policymakers to provide further support for effective and equitable programs for disaster planning. Such a community learning framework integrates multiple theories, such as social learning, expert opinion, and organizational learning and quality improvement theory, within an overall socio-ecological framework.

“Tale of Two Cities” Case Study

The application of the CPPR model to mental health began with the Witness for Wellness (W4W) project, which paved the way for the model to be applied successfully in subsequent programs. This project was designed to address the issue of depression and to begin exploring ways of overcoming the stigma associated with it.42, 48-51 While not implemented in a post-disaster context, W4W was designed and implemented in the resource-poor, urban setting of South Los Angeles. The project was initiated through a planning process that presented to nearly 500 community representatives information on both community-based approaches to address depression and evidence from research studies of collaborative care and other treatment models for depression in low-income minority communities.42 Next, a large planning process49 using multi-stakeholder sharing and consensus methods led to the formulation of 3 community-academic co-led working groups: 1) Talking Wellness addressed social stigma of depression and worked to identify culturally appropriate ways of increasing the dialogue in South Los Angeles about the salience of depression as an issue for community action;48 2) Building Wellness responded to concerns about scarcity of healthcare providers in Los Angeles by developing approaches to support screening and case management for depressed clients through social services settings,51 using as a starting point the quality improvement toolkits from the Partners in Care study;52 and 3) Supporting Wellness developed strategies to bring the issue of depression to the attention of policy makers, and advocate for the support of vulnerable communities to address depression.50 The project led to a number of innovations locally such as use of the arts to engage the community to build collective efficacy to address depression.53 A regular feature of this project was reflection on equity and the salience of race and ethnicity within the project leadership. As one example, the lead community PI was an African American female and the lead academic PI a Caucasian male. Their partnership included many discussions of equalizing power. Community members, after initially wondering about the appropriateness of having a Caucasian academic lead, became very supportive after engaging in an open discussion of concerns about the potential for racism and a history of white supremacy as a threat to the community. The strong partnership of academic and community leaders which grew over time helped to achieve a balance that was often commented on by other leaders and community members at meetings.54, 55 This project had a high representation of unaffiliated community members with high levels of social and/or health needs in leadership and membership positions, who worked regularly with academic leaders and system/clinical leaders from the community. To achieve this, the project had a very strong focus on diversity, trust building, development of common language and concepts, and transparency; and most conflicts arising during the course of this project were over these issues rather than the content of program planning.56

Overall, the W4W initiative illustrated that addressing mental health challenges such as depression in vulnerable communities through a community engagement approach, can be a “win-win”. Community members and agencies gained knowledge of and confidence in addressing depression and familiarity with evidence-based approaches, while researchers and community members worked together on community and academic products concerning mental health. This project gave us confidence in the ability of clinicians and non-clinicians, both community and academic, to work together to plan large-scale mental health improvement initiatives in under-resourced communities. Policymakers were also directly involved in the workgroups, which helped develop opportunities to align community goals with policy opportunities, such as representing community perspectives in large stakeholder processes in Los Angeles County.50

While large scale implementation of the resources developed in the W4W initiative had not yet occurred in Los Angeles, the partnership model and specific tools were developed sufficiently to be helpful as resources to the REACH NOLA MHIT Program, a Red Cross-funded initiative to promote mental health recovery post-Katrina in New Orleans. This initiative’s relationship with the PRC at UCLA/RAND developed because the PRC Center Director was the main mentor for a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholar at UCLA from New Orleans; at the time, the RWJF program had recently expanded to have a major focus on community engagement as a skill for clinician investigators.57 In this context, a new collaboration formed to develop an approach to promote mental health recovery after hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

Post-Katrina New Orleans was an area in great need of mental health services, but with minimal access to such care because of damage to much of the traditional healthcare infrastructure of the city.1-3, 5, 58 The MHIT initiative aimed to address this unmet need and build capacity by activating partnerships among academic institutions including RAND, UCLA and Tulane and community agencies including faith-based organizations, clinics and health centers and social services agencies. MHIT embraced CPPR principles such as power and resource sharing, co-planning of activities by community and academic investigators and formal recognition of community input. For example, as in the W4W initiative, MHIT was led by a steering council comprising community and academic partners to help prioritize project goals and activities. The Council also ensured that specific arrangements were in place to support community and academic partners equally with regards to funding and decision-making. This helped to build capacity as did the experience gained by community and academic partners from contributing to all program phases from inception, relating to funders, implementation, assessment and dissemination of products or results.

MHIT grew out of an initial one-year post storm assessment of need for services in New Orleans, which identified high unmet need for mental health services as a key recovery issue.58 To address those needs, MHIT integrated prior evidence-based approaches to improving quality of care and outcomes for depression at a systems level - Partners in Care,52 We Care,59 and IMPACT.60 However, because of the lack of stable healthcare infrastructure even one-year post-Katrina and trust issues among the communities most heavily affected by the disaster, the CPPR model as developed in the W4W initiative helped to inform the overall approach to MHIT. MHIT, however, was funded specifically to build services capacity and thus offered an opportunity to implement the lessons from W4W at some scale. Using a community engagement approach modified for the unique, post-storm environment in New Orleans, MHIT provided training in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for depression, medication management, team management of depression, and case management skills including screening for depression and other health and life difficulties, behavioral activation and problem solving, outcomes tracking and other relevant skills. A significant accomplishment of MHIT was the development of a community health worker/outreach worker manual to support screening, education, outcomes tracking, referral and the basics of behavioral activation and problem solving at a much broader scale.61 MHIT implemented 75 trainings over two years involving over 400 providers in community-based agencies and potentially reached over 110,000 community members with improvements in outreach, screening, assessment and treatment and/or case management or support for depression and trauma-related symptoms.58 Achieving capacity building at this scale also required developing relationships with local and state-level policy makers as well as clinicians and community leaders. In addition, this project brought awareness that the providers being trained oftentimes had the same issues in terms of post-disaster consequences for mental health as the clients they were serving. The repeated exposure through services provision to others in distress posed challenges to providers who themselves were at risk for distress post-trauma. In response, we also developed an approach to provider self-care as a routine part of trainings, using alternative therapies and simple strategies such as training in behavioral activation to assist coping strategies. Like the Witness for Wellness initiative, this services demonstration also had strong representation of community members although many held a leadership role, whether heading a neighborhood association or providing volunteer or professional case management services. However, in the context of recovery from a disaster most participants were simultaneously serving several roles, such as being a provider or staff member while also being a community member directly affected by the disaster. For this reason, the project was designed to be flexible in expectations as people participated or withdrew due to these different roles and needs.

This substantial experience in implementation of evidence-based or informed services delivery strategies for depression in New Orleans were brought back to Los Angeles and incorporated into the next generation study after Witness for Wellness, Community Partners in Care.39, 43, 62 CPIC was the main partnered scientific goal that emerged from W4W, which was to determine the unique added value of community capacity building under a CPPR model over and above more standard, individual agency training to address depression. CPIC was a randomized trial, itself conducted under CPPR principles and structure, in which nearly 100 programs in Los Angeles providing primary care/public health, mental health, substance abuse, or social services, as well as other community-based agencies such as faith-based, senior centers, exercise clubs or hair salons were randomized to one of two models of implementing collaborative care for depression: 1) individual agency assistance through webinars and site visits; or 2) a period of collaborative planning across all assigned agencies to fit the partnered training plan to the needs and strengths of the community. Outcomes were then tracked over a year at both provider/agency and client levels; results are still pending. The project is being conducted in both South Los Angeles, the site for the W4W study, and in Hollywood-Metropolitan Los Angeles. Both communities have substantial representation of Latinos and African Americans. The wide range of programs represented in this study were a result of community input suggesting that this was the range of programs relevant to persons with depression living in the community;43 and this range was similar to that of programs participating in trainings in the New Orleans MHIT project. While MHIT did not have a strong outcomes research component, as it was not a research study but a services project, the CPIC study did and was designed as a randomized trial.

To support this range of agencies in identifying components of collaborative care relevant to their scope, we used our extensive implementation experience in New Orleans, and the resources developed there such as the Health Worker manual, to inform further adaptations for CPIC. This was particularly appropriate because issues of cultural competence and trust were salient in the Los Angeles and New Orleans environments and while not suffering the consequences of a major disaster, the Los Angeles communities faced many highly stressful issues common in under-resourced urban communities of color. In addition, since CPIC providers often lived in the same communities and faced many of the same stresses as their clients, we used the provider self-care strategies developed in MHIT and faced similar issues in terms of participants serving multiple roles that needed acknowledgement and accommodation in the process and structure. In CPIC, much of what was new above and beyond the adaptations of the collaborative care models from prior projects was the extensive development of a community-partnered approach to designing and conducting a group-randomized trial; this had not been a component of W4W or MHIT. This experience in community engagement in designing a randomized trial combined with the mental health recovery work in New Orleans led to an opportunity to address disaster preparedness from a community resiliency perspective in the Los Angeles Community Disaster Resilience (LACCDR) initiative.

LACCDR has developed a community disaster resilience approach to disaster preparedness using the CPPR model in Los Angeles and like CPIC is following the approach of a participatory public health trial.63 Like W4W, MHIT and CPIC, LACCDR is led by a steering council, which developed three workgroups in its first year to engage stakeholders and identify priorities for building resilient communities. Key stakeholders include first responders, neighborhood watch members and representatives from faith-based organizations, the business community, and representatives of vulnerable populations. The community engagement approach to developing the LACCDR design is described elsewhere.64 One key difference between the prior CPPR-informed efforts described above and LACCDR, is that LACCDR grew out of the initiative of public health policymakers, so the policy support is present from the outset.

LACCDR is designed to explore how to implement a community resiliency approach to disaster preparedness overall, and to compare the results for partnerships and community preparedness from a state-of-the art, traditional individual/family preparedness initiative with a broad community-resilience initiative in comparable communities. As a preparedness project led by the public health department, LACCDR has a strong focus on responder agencies and their staff and volunteers, who work closely with diverse communities to achieve community disaster resilience goals. These goals include improved organizational relationships, salient connections to community leaders and members and communication strategies to improve access to information and resources. For the purposes of this paper, LACCDR represents the next step in the cycle of projects focusing on community engagement for improving mental health and/or disaster response. Although LACCDR does not have a primary mental health focus, it includes a focus on personal and organizational relationships as part of community resilience. In addition, provision of psychological first aid10 is one core component of the community resiliency toolkits being developed for the pilot demonstration.

LACCDR is also using the CPPR model and some of its adaptation for the community engagement intervention from CPIC to inform its community resiliency intervention model. As an initiative instituted by a policy and services agency, LACCDR has had somewhat less focus on inclusion of unaffiliated community members or those in need of services as participants to date. However, some workgroup leaders are from community-based organizations such as churches or community clinics as well as from advocacy organizations for under-resourced communities and special populations.

Implications and Lessons Learned

Our “tale of two cities” has led to many lessons learned concerning the feasibility of a community learning approach to mental health issues in general and to disaster response in particular, with implications for communities, policymakers and clinicians. Because of the integrated, partnership approach that has evolved iteratively over time, those lessons have emerged from the perspective of diverse stakeholders interacting with each other (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Community Engagement (CE) Issues and Lessons Learned

| CE Issue | Strategy | Challenge | Lesson learned |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joint leadership | Include community and academic members in all meetings | Members with demanding schedules may not always be available | Embrace the “on the bus, off the bus” model, which recognizes that members can participate as feasible and welcome inclusive participation to sustain project activities. |

| LACCDR: Strong focus on first responders | Recruit volunteer first responders | First responders are accustomed to top down approach vs bottom up approach applied in CE projects | Pair first responders from government agencies ho operate under hierarchical structures with volunteer responders to balance perspectives. |

| Shared decision-making | Executive Steering Council of community and academic members | Community and academic representation may not be equal | Diversify ways of giving input for decisions (email, phone participation; proxy votes) or as needed delay until fuller input is obtained, out of respect for the partnership. |

| CPIC: Diverse leadership | Community leaders support each other | Academic leaders may tend to dominate | Pair academic leaders with multiple community co-leads who balance/spell each other. |

| Resource-sharing | Provide subawards or consultant payments to partners | Tensions may arise due to perceived inequity in distribution of funds | Transparent budget review, pro-active planning to balance resources and communicate goals to funders. |

| MHIT: Provide resources to enable community participation | Subawards and consultant payments to partners | Learning curve for smaller agencies in managing funds and complying with policy | Designate an experienced agency to manage and distribute funds among smaller community based organizations. |

| Create shared Vision | CE activity (similar to an icebreaker) | Find activities that build relationships while supporting mission and are culturally appropriate. | The most effective CE activities are symbolic of project aims, encourage people to think creatively and get people out of their seats and are jointly led. |

| All projects: CE exercise | Brief activity that gets people thinking as a group | Academics may initially resist non-traditional meeting activity | Have project leaders/investigators lead the CE exercise to level the playing field and help meeting participants to be engaged. |

| Trust | Identify “win-wins” to demonstrate that community and academic goals are equally valued | May require modification of initial project aims | Training resources that combine scientific evidence base and community knowledge can yield a strong basis for increased use of current evidence-based practices in resource-poor communities. |

| CPIC: Outsider concerns | Partner with trusted community member | Larger community may view community member as selling out | Conduct partnered meetings and trainings at community sites to obtain community feedback throughout project. |

| Recognition of input | Include community and academic members as co-authors and celebrate products | Author order may be a source of tension, especially among academics; community products may be unfamiliar to academics | Dissemination activities such as co-authored presentations and papers enhance the likelihood of reaching critical audiences and lend validity to future efforts and thus future products, while building trust and respect in the partnership. |

| MHIT/PRC: Disseminating findings | Publication of a special issue | Delays in finalizing manuscripts due to large partnerships as authors | Designate a single point-person to field questions, circulate drafts of manuscripts and integrate partner feedback. |

Mental Health as a concern

Our experience suggests that while many agree that mental health is a key issue both in general and after disasters and in planning for disasters, working with community is critical to defining the issue and identifying the appropriate language to use in uncovering what mental health and psychological issues mean in community. In some communities affected by disaster, the notion of mental health as an issue (current or future) may be unexpected or even at times denied as a reality. In part this may be because of other pressing and immediate issues, such as housing crises, schools that were destroyed or levees that failed. As a result, it may require deliberate investigation with affected community members to identify that mental health is (or is not) a significant issue for the population at that time. Further, it may require looking beyond words to behaviors and interactions together.

Trust and Capacity issues

There can be substantial insider-outsider dynamics following some disasters that may complicate trust concerns in attempting to build capacity for or provide mental health services. Key to the public approach is early engagement with vulnerable communities before a disaster to collaboratively build a common understanding of the challenges, define the problems and build capacities to improve resilience. Many people in more normal circumstances are already reluctant to discuss mental health owing to stigma. Discussing research or even health care in community settings even in a non-disaster situation can be fraught with concerns about unequal power dynamics, histories of abuse, and other legitimate concerns, particularly in low income communities and communities of color. The imposition of a disaster on top of those usual strains may magnify the sense of disparity regarding who is really part of the community and who is an outsider.

Efforts to build trust can overcome those issues, but the sacrifice and investment of time is not necessarily commonplace in disaster response. This is why trust must be built before a disaster. The FEMA whole of community planning strategy is to incorporate pre-disaster collaboration between responders and community residents. It may be simpler for a responder agency to provide funding to local agencies to ensure that some services are delivered, as funding agencies may prefer organizations with a solid financial track record, but then the opportunity to build capacity among the most affected agencies which are trusted among the most impacted populations can be lost. Depending on the disaster, this may be hard to come by post-disaster and approaches are needed to work directly with community-based organizations working in low income settings. One approach that we used post-Katrina in New Orleans was to partner with some medium to larger size agencies and also use a nonprofit research firm (RAND) to partner in managing accountability for smaller agencies.

Research and Evaluation

In disaster research, relatively few people living in disaster impacted communities want to spend time being counted so that lessons can be learned and applied to inform future circumstances. There are substantial efforts to engage post-disaster communities in research, but not all have been successful in recruiting participants.65 Additionally, different communities will prioritize hazards differently and agencies must be responsive to this dynamic. We have learned in the CPIC study and in MHIT that partnered approaches can help overcome these issues, but in the context of programs that built real-time capacity for addressing needs through trainings at scale and with substantial investment of resources in community partners through a co-led enterprise; this requires additional effort and expertise that are uncommon to date. In the future, such efforts will become more common given the new policy directive at FEMA and CDC.

Provider/Clinician Development Issues

We found it feasible to engage large numbers of providers in diverse organizations in capacity building for evidence-based collaborative care for depression in MHIT and CPIC. Both of these projects made substantial adjustments to prior research-based implementation strategies such as simplifying language or tailoring specific components to the actual work scope of a given provider or program. The main modification needed for the disaster and/or under-resourced community context was adding provision of support for provider self-care as many of the providers faced similar stresses to their clients, identified with them or had actually survived the same disaster. Thus, part of the provider development and capacity building issues to address mental health are to anticipate this need. We also determined across projects, that providers in community-based settings can make excellent training partners to academic experts in leading community trainings. They understand the local context and needs of providers in similar agencies, increasing the relevance of trainings and fit to community assets and capacities. However, the success of capacity building was also directly tied to efforts to maintain culturally competent trainings and services, which took considerable time beyond the usual trainings in evidence-based practice to develop and maintain. From LACCDR, we have learned that tools and capacity building activities must have real time as well as disaster utility.

Community Transparency and Leadership

A signature feature of all of these projects was attention to what is referred to in CPPR as transparency, or finding a community language, to arrive at common meanings for concepts, products and other outcomes such as toolkits or evaluation findings. Given histories of distrust and stressful circumstances in under-resourced communities for the consequences of disasters, the sustained effort to communicate important concepts, needs and approaches and to reach agreements on how best to move forward together were crucial to collaborating in trainings and services delivery. The commitment to transparency might be viewed as at the heart of the co-leadership that emerged in all the projects. Consistently, strong community leaders emerged who led the charge for attending to mental health issues and often became leaders more broadly as a result. This leadership development in the community over sensitive matters such as mental health and depression was one of the striking developments across projects. In this respect, the projects outlined above were about much more than developing an approach to disaster or mental health. They were more like a demonstration of the broader principle of the value of developing human capital in diverse forms to address important mental health and community resilience needs.

Each of the projects faced a somewhat different course of development regarding community leadership and participation of more “grass roots” or unaffiliated community members. For W4W, the open meetings in the community attracted many unaffiliated community members into early leadership roles.

For MHIT, the urgency and commonality of the disaster experience mobilized many providers as well as informal community leaders such as from faith-based organizations. For CPIC, because it was conducted as a partnered research initiative with broad reach into diverse community-based organizations, community members and staff of diverse organizations, stepped into leadership and group member roles early on. LACCDR as directed from a policy/services agency has somewhat greater representation of agency leaders and responders. A lesson learned here is that the public health department had to undergo an internal culture change to fully embrace and align with a community partnered approach to building resilience. Across all projects, many agency leaders and responders served dual roles as persons directly affected by disasters or stressors. Thus across projects, the salience of distinguishing between community leader, member and even researcher is often blurred. We have learned that these multiple roles are beneficial in setting project goals and can make them more community relevant by asking individuals for their own goals from multiple perspectives, personal, agency or community.

Policymakers and Funders

For policymakers as well as funders, a key lesson learned is the time required to establish and maintain authentic partnerships, whether for services, research or both, and within those partnerships to tackle substantial, sensitive issues such as concerns with depression or psychological consequences of trauma. Especially in the context of vulnerable populations, the level of trust development required, and “insider-outsider” dynamics following disasters, necessitates an approach that is both responsive to urgent needs as feasible but takes a long-term view of the value of relationships and investments in mental health. Fortunately, in the projects we have described we had the support of funding agencies and policymakers to explore how to achieve a community engagement focus within our work and any measure of success that we have achieved is due in no small part to their support. For LACCDR, the fact that public health policymakers committed at the outset to this direction has been quite key as we face the challenges inherent in blending perspectives of responders, community members, traditional providers and community leaders, and evaluators.

Overall, our “tale of two cities” has suggested that diverse partnerships can organize around goals to improve community and individual outcomes. We have learned the many lessons shared here in applying this model to address mental health problems and disaster recovery and are now in the early stages of applying this model to preparedness and community resiliency.

Awareness of the impact of disasters globally on mental health is increasing.

Known difficulties in preparing communities for disasters and a lack of focus on relationship building and organizational capacity in preparedness and response have led to a greater policy focus on community resiliency as a key public health approach to disaster response.

This perspective emphasizes relationships, trust and engagement as core competencies for disaster preparedness and response/recovery.

Our approach has a specific focus on behavioral health and relationship building across diverse sectors and stakeholders concerned with under-resourced communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank their partners for making this work possible. This work was supported by NIH Research Grant # P30MH082760 and R01MH078853 funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, Red Cross Grant # BHGP-08-006 and CDC Grant # 2U90TP917012-11.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kenneth B. Wells, Center for Health Services and Society, University of California, Los Angeles Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior; Department of Health Services, University of California, Los Angeles School of Public Health; RAND Health, RAND Corporation.

Benjamin F. Springgate, RAND Health, RAND Corporation.

Elizabeth Lizaola, Center for Health Services and Society, University of California, Los Angeles Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior.

Felica Jones, Healthy African American Families.

Alonzo Plough, Emergency Preparedness and Response, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

References

- 1.Chandra A, Acosta JD. Disaster recovery also involves human recovery. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304(14):1608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobfoll S, Watson P, Bell C, et al. Five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: empirical evidence. Psychiatry. 2007;70(4):283–315. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2007.70.4.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore M, Chandra A, Acosta J. Building community resilience: what can the United States learn from experiences in other countries? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2012.15. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users: socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public Health Reports. 2002;117(Suppl 1):S135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981-2001. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2002;65(3):207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reissman DB. New roles for mental and behavioral health experts to enhance emergency preparedness and response readiness. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2004;67(2):118–122. doi: 10.1521/psyc.67.2.118.35956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler R, Galea S, Gruber M, Sampson N, Ursano R, Wessely S. Trends in mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Molecular Psychiatry. 2008;13(4):374–384. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neria Y, Galea S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(4):467–480. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine. Preparing for the psychological consequences of terrorism: a public health strategy. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schreiber M, Gurwitch R, Wong M. Listen, Protect, Connect--Model & Teach: Psychological First Aid (PFA) for Students and Teachers. US Department of Homeland Security; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.King M, Schreiber M, Formanski S, Fleming S, Bayleyegn T, Lemusu S. Surveillance and traumatic experiences and exposures after the earthquake-tsunami in American Samoa. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2012.11. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abramson D, Stehling-Ariza T, Garfield R, Redlener I. Prevalence and predictors of mental health distress post-Katrina: findings from the Gulf Coast Child and Family Health Study. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2008;2(2):77–86. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e318173a8e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benight C, Ironson G, Durham R. Psychometric properties of a hurricane coping self-efficacy measure. J Trauma Stress. 1999;12(2):379–386. doi: 10.1023/A:1024792913301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi P, Lewin S. Disaster, terrorism, and children: Addressing the effects of traumatic events on children and their families is critical to long-term recovery and resilience. Psychiatric Annals. 2004;34(9):710–716. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acosta J, Chandra A, Feeney KC. Navigating the road to recovery: assessment of the coordination, communication, and financing of the disaster case management pilot in Louisiana. Rand Corp; 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandra A, Acosta J. The role of nongovernmental organizations in long-term human recovery after disaster: reflections from Louisiana four years after Hurricane Katrina. Vol. 277. Rand Corp; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinclair J, Bixler D, Cummings KJ, Ridenour ML. Displacement of the underserved: medical needs of Hurricane Katrina evacuees in West Virginia. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2007;18(2):369–381. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis JR, Wilson S, Brock-Martin A, Glover S, Svendsen ER. The impact of disasters on populations with health and health care disparities. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness. 2010;4(1):30. doi: 10.1017/s1935789300002391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobfoll S, Palmieri P, Johnson R, Canetti-Nisim D, Hall B, Galea S. Trajectories of resilience, resistance, and distress during ongoing terrorism: the case of Jews and Arabs in Israel. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(1):138–148. doi: 10.1037/a0014360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoenbaum M, Butler B, Kataoka S, et al. Promoting mental health recovery after hurricanes Katrina and Rita: what can be done at what cost. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):906–914. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang P, Gruber M, Powers R, et al. Mental health service use among hurricane Katrina survivors in the eight months after the disaster. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(11):1403–1411. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.11.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Everly GS, Jr, Phillips SB, Kane D, Feldman D. Introduction to and overview of group psychological first aid. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2006;6(2):130. [Google Scholar]

- 23.FEMA. National Disaster Recovery Framework. 2011 Sep;:1–116. [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services. National Health Security Strategy of The United States of America. 2009 Dec; [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfefferbaum R, Reissman D, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche F, Norris F, Klomp R. Factors in the development of community resilience to disasters. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim S, Flaskerud JH, Koniak-Griffin D, Dixon EL. Using community-partnered participatory research to address health disparities in a Latino community. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2005;21(4):199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nyamathi A, Koniak-Griffin D, Ann Greengold B. Development of nursing theory and science in vulnerable populations research. Annual Review of Nursing Research. 2007;25(1):3–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pieters HC, Heilemann MSV, Grant M, Maly RC. Older women’s reflections on accessing care across their breast cancer trajectory: navigating beyond the triple barriers. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2011;38(2):175–184. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.175-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pieters HC, Heilemann MSV, Maliski S, Dornig K, Mentes J. Instrumental relating and treatment decision making among older women with early stage breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.E10-E19. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minkler M. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watkins KE, Hunter SB, Hepner KA, et al. An effectiveness trial of group cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with persistent depressive symptoms in substance abuse treatment. Archives of general psychiatry. 2011;68(6):577. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Institute of Medicine. Promoting health: intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker E. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smedley BD, Syme SL. Promoting health: intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tunis S, Stryer D, Clancy C. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(12):1624–1632. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wells K, Miranda J, Bruce M, Alegria M, Wallerstein N. Bridging community intervention and mental health services research. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(6):955–963. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zerhouni E. Translational and clinical science--time for a new vision. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005a;353(15):1621–1623. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb053723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zerhouni E. US biomedical research: basic, translational, and clinical sciences. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005b;294(11):1352–1358. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.11.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones L, Wells K, Norris K, Meade B, Koegel P. The vision, valley, and victory of community engagement. Ethnicity & Disease. 2009;19(Suppl):S6-3–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wells K, Jones L. “Research” in community-partnered, participatory research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302(3):320–321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moini M, Fackler-Lowrie N, Jones L. Community engagement: moving from community involvement to community engagement—a paradigm shift. PHP Consulting; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bluthenthal R, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie N, et al. Witness for Wellness: preliminary findings from a community-academic participatory research mental health initiative. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(Suppl):S18–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung B, Ngo V, Ong M, et al. Effects of community engagement and planning versus technical assistance to implement collaborative care for depression on training participation: A group-level randomized trial in safety-net agencies in Los Angeles. In preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Springgate B, Wennerstrom A, Meyers D, et al. Building community resilience through mental health infrastructure and training in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethnicity & Disease. 2011;21(Suppl 1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lizaola E, Schraiber R, Braslow J, et al. The Partnered Research Center for Quality Care: developing infrastructure to support community-partnered participatory research in mental health. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(3 Suppl 1):S1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: Toward antiracism praxis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1) doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas SB, Quinn SC, Butler J, Fryer CS, Garza MA. Toward a fourth generation of disparities research to achieve health equity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:399–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung B, Corbett CE, Boulet B, et al. Talking wellness: a description of a community-academic partnered project to engage an African-American community around depression through the use of poetry, film, and photography. Ethnicity and Disease. 2006;16(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel KK, Koegel P, Booker T, Jones L, Wells K. Innovative approaches to obtaining community feedback in the Witness for Wellness experience. Ethnicity and Disease. 2006;16(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stockdale S, Patel K, Gray R, Hill DA, Franklin C, Madyun N. Supporting wellness through policy and advocacy: a case history of a working group in a community partnership initiative to address depression. Ethnicity and Disease. 2006;16(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones D, Franklin C, Butler BT, Williams P, Wells KB, Rodriguez MA. The Building Wellness Project: a case history of partnership, power sharing, and compromise. Ethnicity and Disease. 2006;16(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chung B, Jones L, Jones A, et al. Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wells K, Jones L. Commentary: “research” in community-partnered, participatory research. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302(3):320–321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones L, Wells K, Norris K, Meade B, Koegel P. The vision, valley, and victory of community engagement. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(4 Suppl 6):S6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voelker R. Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Mark 35 Years of Health Services Research. JAMA. 2007;297(23):2571–2573. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.23.2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Springgate BF, Wennerstrom A, Meyers D, et al. Building community resilience through mental health infrastructure and training in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(3 Suppl 1):S1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women. JAMA. 2003;290(1):57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wennerstrom A, Vannoy SD, Allen C. Community-based participatory development of a community health worker mental health outreach role to extend collaborative care in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(Suppl 1):S1–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chung B, Jones L, Dixon E, Miranda J, Wells K Council CPiCS. Using a community partnered participatory research approach to implement a randomized controlled trial: planning community partners in care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):780–795. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katz DL, Murimi M, Gonzalez A, Njike V, Green LW. From controlled trial to community adoption: the multisite translational community trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2011 Jun 16;101(8):e17–27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wells K, Jones L, Chung B, et al. Community-partnered cluster-randomized comparative effectiveness trial of community engagement and planning or program technical assistance to address depression disparities. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2484-3. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Woodward A. Long-term oil disaster study still seeks participants. 2012 Dec 15; http://www.bestofneworleans.com/blogofneworleans/archives/2012/10/02/long-term-oil-disaster-study-still-seeks-participants.