Abstract

A crucial step during the programmed biosynthesis of fungal polyketide natural products is the release of the final polyketide intermediate from the iterative polyketide synthases (iPKSs), most frequently by a thioesterase (TE) domain. Realization of combinatorial biosynthesis with iPKSs requires TE domains that can accept altered polyketide intermediates generated by hybrid synthase enzymes and successfully release “unnatural products” with the desired structure. Achieving precise control over product release is of paramount importance with O—C bond-forming TE domains capable of macrocyclization, hydrolysis, transesterification and pyrone formation that channel reactive, pluripotent polyketide intermediates to defined structural classes of bioactive secondary metabolites. By exploiting chimeric iPKS enzymes to offer substrates with controlled structural variety to two orthologous O—C bond-forming TE domains in situ, we show that these enzymes act as non-equivalent decision gates, determining context-dependent release mechanisms and overall product flux. Inappropriate choice of a TE could eradicate product formation in an otherwise highly productive chassis. Conversely, a judicious choice of a TE may allow the production of a desired hybrid metabolite. Finally, a serendipitous choice of a TE may reveal the unexpected productivity of some chassis. The ultimate decision gating role of TE domains influences the observable outcome of combinatorial domain swaps, emphasizing that the deduced programming rules are context dependent. These factors may complicate engineering the biosynthesis of a desired “unnatural product”, but may also open additional avenues to create biosynthetic novelty based on fungal nonreduced polyketides.

INTRODUCTION

Fungi biosynthesize a large variety of structurally diverse polyketide natural products that mediate various ecological interactions as mycotoxins, virulence factors, and signaling molecules. These compounds are also of a prime interest to the pharmaceutical industry due to their various antibiotic, cancer cell antiproliferative, immuno-suppressive and enzyme inhibitory activities, activities, and have provided the scaffolds for highly successful drugs as well as inspiration for chemical synthesis.1,2 Amongst fungal polyketides, the 1,3-benzenediol lactone family (encompassing the resorcylic acid lactones [RALs] and the dihydroxyphenylacetic acid lactones [DALs]) offer particularly interesting pharmacophores for bioprospecting. For instance, the DAL 10,11-dehydrocurvularin (1, Fig. 1) shows anti-inflammatory and immune system modulatory activities due to its inhibition of the inducible nitric oxide syn-thase.3,4 Both 1 and the RAL monocillin II (2) are also potent inhibitors of the heat shock response, an evolutionarily conserved coping mechanism of eukaryotic cells. By disturbing protein homeostasis, both compounds display promising broad spectrum cancer cell antiproliferative activities in vitro.5–8 Other RALs such as zearalenone and hypothemycin exhibit estrogen agonist and selective mi-togen-activated protein kinase inhibitory activities, respectively.9,10

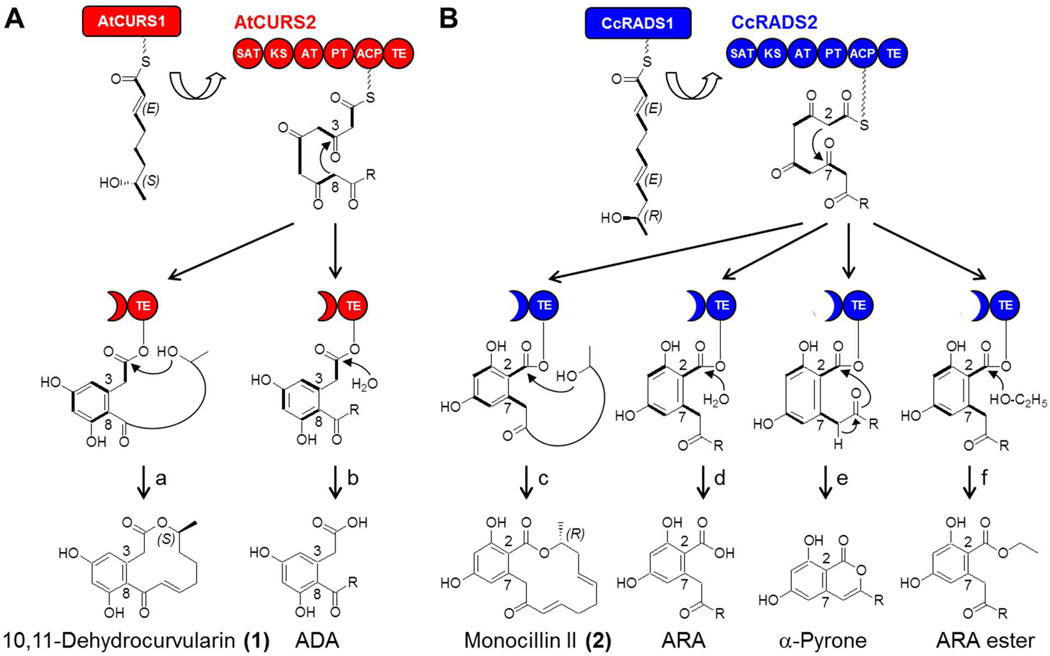

Figure 1.

The role of TE domains during polyketide formation by collaborating iPKSs. (A) The biosynthesis of the DAL 10,11-dehydrocurvularin (1) involves the hrPKS AtCURS1 producing a reduced tetraketide starter unit that primes the nrPKS AtCURS2.13,14 Following four additional condensation events with malonyl-CoA, the first ring is closed by the PT domain 15 in a C8—C3 aldol condensation event in the S-type folding mode.13,16,17 Polyketide products may be released by intramolecular macrolactone formation to yield a DAL like 1 (route a) or by hydrolysis to form an acyl dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (ADA) (route b). (B) Biosynthesis of monocillin II (2) also involves a sequentially acting, collaborating nrPKS pair.18 The pentaketide 19 produced by the hrPKS CcRADS1 is further elaborated by the nrPKS CcRADS2, including C2—C7 condensation in the F-type folding mode.16,20 Product release by macrolactone formation yields a RAL like 2 (route c); hydrolysis provides acyl resorcylic acid (ARA) products (route d); α-pyrones are formed by the attack of the C9 enol on the oxoester (route e); and ARA ethyl esters are produced by utilizing ethanol as the nucleophile (route f).18,21 C-C bonds in bold indicate intact acetate equivalents (malonate-derived C2 units) incorporated into the polyketide chain by the iPKSs.

The biosynthesis of fungal polyketides is catalyzed by iterative polyketide synthases (iPKSs).11 Although the architecture of iPKSs is similar to a single module of bacterial type I modular PKSs,12 the iterative nature of these enzymes is nevertheless analogous to dissociated bacterial type II PKSs.22 While the assembly of most fungal polyketides requires a single iPKS enzyme, the biosynthesis of the polyketide scaffold of both RALs and DALs involves a pair of collaborating iPKS enzymes (Fig. 1).13,18,19,23–26

These iPKSs each harbor a single set of ketoacyl syn-thase (KS), acyl transferase (AT), and acyl carrier protein (ACP) domains, and use these domains iteratively to conduct recursive thio-Claisen condensations of malonyl-CoA extender units. First, a highly reducing iPKS (hrPKS) assembles a reduced linear polyketide chain (Fig. 1). The hrPKS harbors ketoreductase (KR), dehydratase (DH), and enoyl reductase (ER) domains to reduce the nascent β-ketoacyl intermediates in a context-dependent manner to execute a cryptic biosynthetic program.2,27 Next, the reduced polyketide chain is directly transferred from the hrPKS onto a nonreducing iPKS (nrPKS) by the starter unit : ACP transacylase (SAT) domain of the nrPKS.14 After a programmed number of further chain extensions starting with this advanced priming unit, the nrPKS directs ring closure by regiospecific aldol condensation to yield the 1,3-benzenediol moiety, catalyzed by the product template (PT) domain.15,17,20,28 Finally, the thioesterase (TE) domain is responsible for the release of the RAL or DAL product from the nrPKS by closure of the bridging macrolactone ring.29

A crucial step of the programmed biosynthesis of fungal polyketide natural products is the release of the finished polyketide intermediate from the iPKS enzyme, most frequently by a TE domain.2,23,30,31 iPKS TEs feature an α/β-hydrolase catalytic core with a Ser/His/Asp catalytic triad, and a flexible lid loop that closes the substrate binding chamber.12,32 Most TEs from fungal iPKSs catalyze product release by intramolecular C—C bond formation through Claisen/Dieckmann cyclization (TE/CLC domains),28,30,33 in some cases coupled to product truncation by deacylation.32 Nevertheless, a smaller number of fungal iPKSs, including those involved in RAL or DAL biosynthesis,13,18,24,25,34 feature TE domains that catalyze O—C bond formation through macrolactone closure, hydrolysis, and ester or pyrone formation.23,29,31 These O—C bond-forming iPKS TEs are divergent from the TE/CLC domains, with identities <25%. They also share little sequence identity with the O—C bond-forming TEs of the prokaryotic type I modular PKSs and NRPSs, in spite of their functional similarities.18,23,29,35–37

Combinatorial polyketide biosynthesis requires TE domains that can successfully release “unnatural products” by accepting and processing altered intermediates generated by hybrid synthase enzymes.12 Achieving precise control over the mode of product release (macrocyclization, hydrolysis or other mechanisms) is also of paramount importance, considering that this process channels pluripotent, unstable intermediates towards varied polyketide structural classes with defined biological activities. The present work investigated the surprisingly different product release specificities of two closely related O—C bond-forming macrolactone synthase TE domains, one from the nrPKS CcRADS2 involved in the biosynthesis of the RAL 2,18 and the other from AtCURS2 yielding the DAL 1.13 By exploiting a large array of chimeric nrPKS enzymes, we show that these TE domains act as nonequivalent decision gates determining both the shape and the yield of polyketide products.

RESULTS

Macrolactone-Forming TE domains in AtCURS2 and CcRADS2

The O—C bond-forming TE domains of AtCURS2 and CcRADS2 share 52% identity and 64% similarity,13,18 and comparable levels of similarities are also evident with other RAL nrPKSs.24–26 However, sequence identities do not exceed 25% with the C—C bond-forming TE/CLC domains, such as the noranthrone (aflatoxin) synthase nrPKS whose structure has been experimentally determined.30 All RAL/DAL TE domains harbor an invariable Ser/His/Asp catalytic triad (AtCURS2: S1880/H2055/D1907; CcRADS2: S1930/H2109/D1957). In the first half reaction, the polyketide intermediate undergoes transacylation to the Ser nucleophile which is activated by the His catalytic base with the help of the Asp. In the second half reaction, the resulting acyl-O-TE oxoester is attacked by a secondary alcohol of the polyketide chain to afford product release by macrolactone formation. Product release by hydrolysis, ester or α-pyrone (isocoumarin) formation has also been observed.13,17,18,21

The thioester intermediates that serve as substrates for the O—C bond-forming TE domains are structurally complex and may be susceptible to spontaneous rearrangements. To gain insight into the programming of these TE domains, we decided to generate such substrates in situ and to present them to the DAL-forming TEAtCURS2 and the RAL-forming TECcRADS2. Since in trans complementation of dissected domains is known to incur a penalty in product yield and fidelity,1,17,20,38 the TE domains were grafted onto various nrPKSs, created from AtCURS2 and CcRADS2 by domain swaps. These hybrid nrPKSs were then paired with the AtCURS1 or the CcRADS1 hrPKS to create RAL or DAL synthase iPKS pairs. Non-cognate iPKS partners were coupled by interchanging the nrPKS SAT domains.14,39,40 Polyketide production was reconstituted in vivo by expressing these recombinant hrPKS + nrPKS pairs from compatible plasmids in the host Saccharomyces cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA.13,17,19,41

Deletion or inactivation of Claisen cyclase TE domains (TE/CLC) of nrPKSs has been shown to yield variable amounts of α-pyrone shunt metabolites by spontaneous O—C cyclization.1,28,30,32,42 To evaluate the extent of spontaneous product release in the absence of the macrocycle-forming TE domains, we constructed truncated AtCURS2 and CcRADS2 versions. Deletion of TEAtCURS2 completely eliminated polyketide production, while a TE-less CcRADS2 produced only trace amounts of pyrone 7 (< 0.2 mg/l, Fig. S1 traces i and ii). This result indicates that spontaneous product release may not efficiently compensate for the absence of a functional TE with these synthases, similar to what was seen with the CTB1 nor-toralactone synthase or the Pks1 melanin synthase in the absence of their TE/CLC domains.32,43 Thus, the emergence of polyketides in significant amounts during fermentations with recombinant yeasts may be attributed to TE-catalyzed product release in the case of the RAL and DAL synthases, and the polyketide scaffolds of these products could be used to deduce the TE function and specificity.

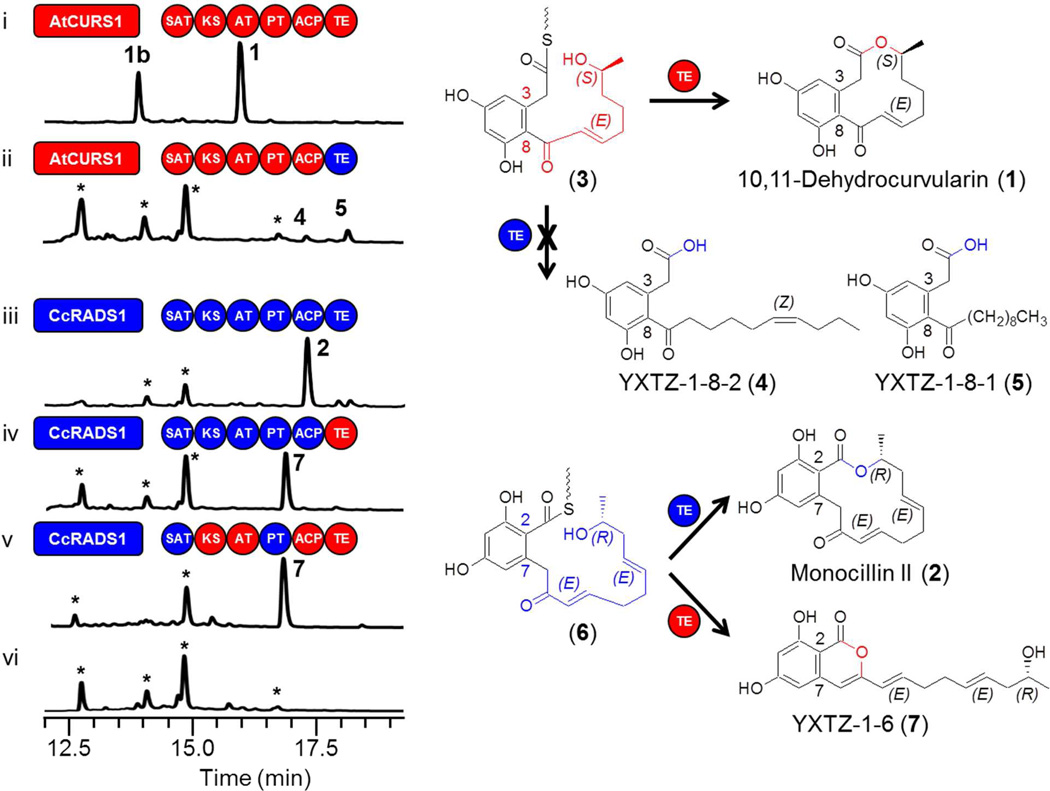

TEAtCURS2 and TECcRADS2 Are Not Equivalent

Surprisingly, replacement of the TE domain of AtCURS2 with TECcRADS2 eliminated the formation of cognate products derived from the expected thioester intermediate 3 (Fig. 2 trace ii). This was not the consequence of an incapacitated nrPKS enzyme as small amounts of the acyl dihydroxyphenylacetic acids (ADA) 4 and 5 were still produced by the strain (0.2 and 0.5 mg/l for 4 and 5, respectively). These products presumably originate from C10 carboxylic acid priming units from fatty acid biosynthesis or degradation in the yeast host. Formation of these and similar ADA in similar yields by hydrolysis (Fig. 1 route b) have already been observed with intact AtCURS2 in the absence of its hrPKS partner,13 similar to the formation of acyl resorcylic acid (ARA) products with the unaccompanied zearalenone nrPKS.23 The lack of the synthesis of cognate products was not due to unproductive interactions between the TECcRADS2 and the ACP or the KS-AT chassis of AtCURS2: replacement of these domains with their CcRADS2-derived equivalents failed to restore the production of 1 (Fig. S1 traces iii and iv).

Figure 2.

TEAtCURS2 and TECcRADS2 are not interchangeable. Product profiles (HPLC traces recorded at 300 nm) of S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA 19,41 co-transformed with engineered or native hrPKS-nrPKS pairs: (i) YEpAtCURS1 and YEpAtCURS2; (ii) YEpATCURS1 and YEpYX8; (iii) YEpCcRADS1 and YEpCcRADS2; (iv) YEpCcRADS1 and YEpYX6; (v) YEpCcRADS1 and YEpYX65; (vi) no-PKS control. The hrPKS-generated portions of the proposed ACP-bound thioester intermediates are color-coordinated with the synthase. The peak in trace (i) labeled with 1b corresponds to 11-hydroxycurvularin, a spontaneous hydration product of 1 13 Peaks labeled with a star represent yeast metabolites unrelated to the iPKS products. Domains drawn as red circles are derived from AtCURS2, while those in blue are from CcRADS2.

The converse experiment, replacement of the TE domain of CcRADS2 with TEAtCURS2 eliminated the formation of 2 but afforded the isocoumarin 7 in a high yield (Fig. 2 trace iv, 3 mg/l). Thus, although TEAtCURS2 was able to process intermediate 6 by pyrone formation using the C9 enol as a nucleophile (Fig. 1 route e),42 macrocycle formation was apparently inhibited. Replacement of the KS, AT and ACP chassis of the enzyme played no role in determining the nature or the amount of the product (Fig. 2 trace v, yield of 7 approx. 3.5 mg/l). Taken together, these experiments show that in spite of the high similarity and phylogenetic proximity of TEAtCURS2 and TEC-cRADS2, these enzymes are not freely interchangeable during combinatorial biosynthesis for creating RAL or DAL products.

Role of the hrPKS-Derived Reduced Acyl Chain

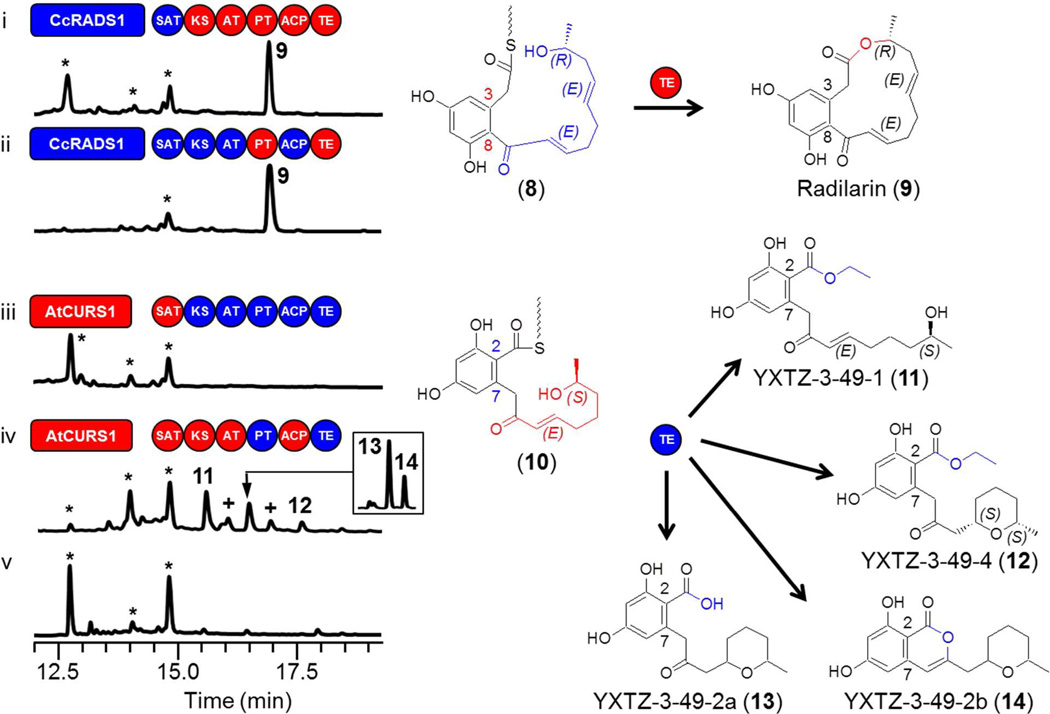

In the previous set of experiments, the TE domains were challenged with the putative ACP-bound acyl thioesters 3 and 6. These thioesters differ in the length and structure of the acyl chain assembled by the hrPKS (a tetraketide for 3 and a pentaketide for 6, Fig. 1), as well as in the aldol condensation register of the 1,3-benzenediol moiety generated by the nrPKS.16,17,20 To disentangle the roles of these two variables in TE substrate recognition and processing, we have created hybrid iPKS pairs where the priming unit for RAL/DAL biosynthesis is assembled by the hrPKS from the other biosynthetic system, while the aldol condensation register is maintained for the selected TE. Thus, the presumed thioester 8 (Fig. 3) is formed from a reduced pentaketide chain as in radicicol, but the register of aldol condensation is C8—C3 (S-type folding) as in 1.16,17 TEAtCURS2 had no difficulty in processing thioester 8 to the novel DAL radilarin (Fig. 3 trace i, 9 mg/l) by macrocycle formation (Fig. 1 route a). As before, replacing the KS / AT / ACP chassis did not influence product yield (Fig. 3 trace ii). Biosynthesis of 9 is remarkable as no 14-member DAL is known from natural sources, thus 9 represents a unique class of truly unnatural products.

Figure 3.

Influence of the reduced acyl priming chain on TE-catalyzed product formation. Product profiles of S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA19,41 co-transformed with hrPKS-nrPKS pairs: (i) YEpCcRADS1 and YEpYX24; (ii) YEpCcRADS1 and YEpYX67; (iii) YEpAtCURS1 and YEpYX12; (iv) YEpAtCURS1 and YEpYX49; (v) no-PKS control. The hrPKS-generated portions of the proposed ACP-bound thioester intermediates are color-coordinated with the synthase. Domains drawn as red circles are derived from AtCURS2, while those in blue are from CcRADS2. Insert: The mixture of 13 and 14 may be separated by HPLC using a linear gradient of 5% to 95% CH3CN in H2O over 40 min. *, Yeast metabolites unrelated to the iPKS products. +, Compounds decomposed during isolation.

Conversely, challenging TECcRADS2 with an intermediate that features a shorter acyl chain on a benzenediol formed in the C2—C7 register (thioester 10 with F-type folding)16,17 seemed initially unproductive when using the CcRADS2 chassis (Fig. 3 trace iii). Fusing this chassis with TEAtCURS2 or the ACP-TE didomain from AtCURS2 was similarly unproductive (Fig. S1 traces v and vi), hinting at a suboptimal interaction of the KSCcRADS2 domain with the incoming tetraketide presented by the SA-TAtCURS2.38 However, replacing the KS / AT / ACP chassis with that of AtCURS2 (Fig. 3 trace iv) led to the production of a variety of ARA products by hydrolysis (13, 0.4 mg/l), or nucleophilic attacks by ethanol (11 and 12, 1.5 and 0.5 mg/l, respectively) or by the C9 enol (14, 0.2 mg/l). Product release by transesterification with alcohols (mainly ethanol) present in the media has been documented for AtCURS2 and the zearalenone nrPKS.13,23,29 Thus, TECcRADS2 is capable of downloading a C2—C7 intermediate with a shorter acyl chain, but macrolactone formation with the foreign substrate is apparently inhibited. Taken together, these experiments indicate that product release by these TE domains in a combinatorial biosynthetic context is permissive to variation of the length and identity of the priming acyl chain, as has been shown with the isolated zearalenone synthase nrPKS23 and with dissected nrPKS hybrids in vitro.43 However, macrocycle formation may be limited by the correct positioning of the distal alcohol of the polyketide chain for nucleophilic attack on the oxoester within the TE catalytic chamber.

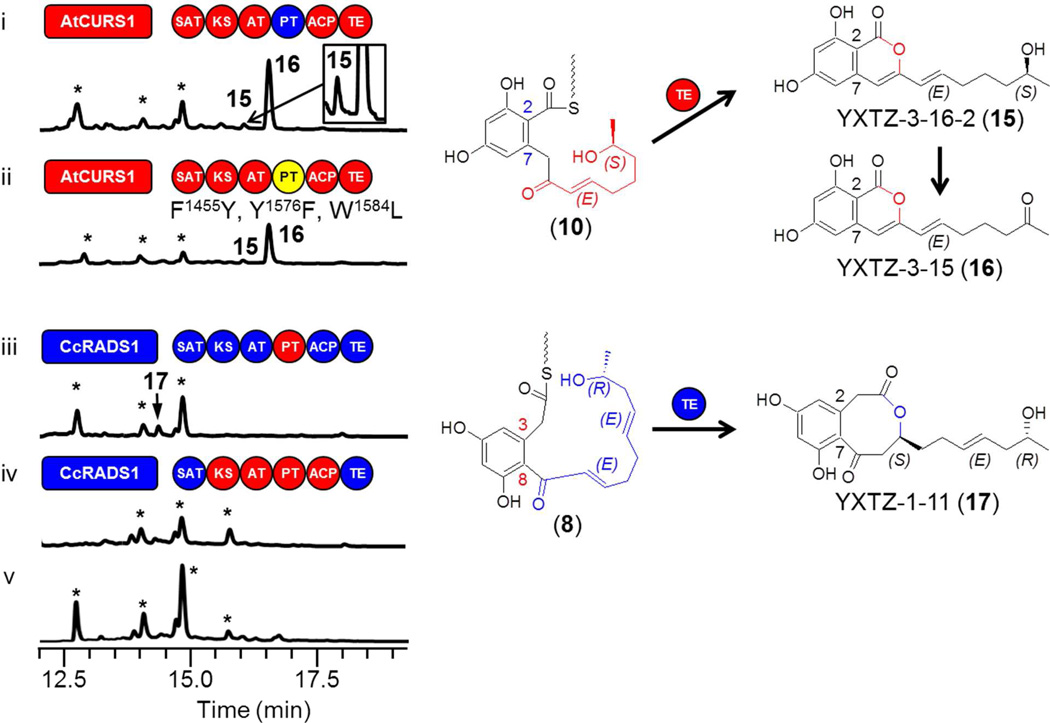

Role of S- or F-Type Folding of the First Ring

Next, we investigated the role of the configuration of the substituted 1,3-benzenediol moiety on product formation by the TE domains. Thus, we created hybrid biosynthetic systems where each TE is challenged with a thioester intermediate featuring a hrPKS-derived acyl chain cognate to that TE, but with a first ring that had formed in the opposite aldol register.13 When intermediate 10 with a C2—C7 geometry was offered to TEAtCURS2, isocoumarins 15 and 16 were formed in good yields (0.3 and 3 mg/ml, respectively, Fig. 4 trace i), as already observed in our recent work on the rational engineering of aldol cyclization by PT swaps.17 16 is formed by a chance oxidation of the C15-OH of 15, catalyzed by an endogenous host enzyme.17 Conversely, offering the C8—C3-cyclized intermediate 8 to TECcRADS2 afforded small amounts of 17 (Fig. 4 trace iii, 0.3 mg/l), where the C8—C3 dihydroxyphenylacetic acid moiety is bridged by an 8-membered lactone.17 Whether the formation of the 4-oxo-2-oxacyclooctane ring of 17 by the facile attack of the C1 carboxyl on the C11 enone is spontaneous or involves TECcRADS2 is unclear at this point. Replacing the KS / AT /ACP chassis with the one from AtCURS2 failed to increase product formation (Fig. 4 trace iv). In any case, low level production of 17, or absence of product formation is not due to an enfeebled chassis as shown by vigorous product formation when these same chassis are paired with TEAtCURS2 (Fig. 3 traces i and ii). Collectively, these experiments indicate that the register of the PT- catalyzed aldol ring formation is an important determinant for the productivity of a given TE in a combinatorial context. Thus, TECcRADS2 is incompetent in forming the desired DAL (or even an ADA) with the S-type substrate 8 even if the priming acyl chain is appropriate for this TE. Similarly, although TEAtCURS2 can effectively download C2—C7-cyclized intermediates like 6 and 10 to form pyrone products like 7 and 15 (compare Fig. 2 trace iv and v with Fig. 4 trace i), macrolactone formation is inhibited. Future studies would need to determine whether the improper configuration of the substrate itself, or the absence of proper protein-protein contacts between the PT and TE domains12 is more important to hinder macrocycle formation. However, it is remarkable that macrocyclization of thioester intermediate 10 is still inhibited with an AtCURS2 derivative harboring only three point mutations in its PT domain (Fig. 4 trace ii). These point mutations in the active site pocket of the PT domain are sufficient to bring about an F-type folding and C2—C7 cyclization, instead of the native S-type folding and C8—C3 first ring closure.17 However, they are unlikely to disturb the native domain-domain interactions between PTAtCURS2 and TEAtCURS2, implying an essential role for direct substrate recognition to determine the mode of product release by the TE.

Figure 4.

Influence of the aldol register of the first ring on TE-catalyzed product formation. Product profiles of S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA19,41 co-transformed with hrPKS-nrPKS pairs: (i) YEpAtCURS1 and YEpAtCURS2-PTCcRADS2; (ii) YEpAtCURS1 and YEpAtCURS2(F1459Y,Y1576F,W1584L); (iii) YEpCcRADS1 and YEpYX11; (iv) YEpCcRADS1 and YEpYX33; (v) no-PKS control. *, Yeast metabolites unrelated to the iPKS products. The hrPKS-generated portions of the proposed ACP-bound thioester intermediates are color-coordinated with the synthase. Domains drawn as red circles are derived from AtCURS2, while those in blue are from CcRADS2. The PT domain in (ii) drawn as a yellow circle is the F1459Y/Y1576F/W1584L mutant of PTAtCURS2.

Combinations of Altered Acyl Chains and Aldol Registers

As shown above, combination of a longer (pentaketide) acyl primer chain and a non-cognate first ring geometry (as in 6) is not an impediment to efficient product release by pyrone formation with TEAtCURS2 (Fig. 2 traces iv and v). Conversely, both macrolactone formation and product downloading is eliminated when an intermediate with an S-type first ring and a shorter starter chain is presented to TECcRADS2 (Fig. 2 trace ii, intermediate 3). This indicates that the effects of acyl chain alterations are additive with the impacts of the modification of the first ring register. Thus, TEAtCURS2-catalyzed product downloading is efficient for both octa- and nonaketide intermediates regardless of aldol register (1, 7, 9, and 15) but macrocycle formation is only detected with S-type (C8—C3) thioester intermediates (1 and 9). TECcRADS2 is a more stringent catalyst that prefers a nonaketide intermediate. It may still download an octaketide, but is apparently unable to form a macrolactone with such a shorter intermediate (11 to 14, Fig. 3 trace iv). S-type (C8—C3) aldol intermediates are not preferred substrates either, and products may only be released if the intermediate is a nonaketide. Even then, products emerge only in small amounts by hydrolysis (4 and 5, Fig. 2 trace ii) or by formation of an 8-membered ring (17, Fig. 4 trace iii).

TE Domains May Reveal Unexpected Biosynthetic Interactions

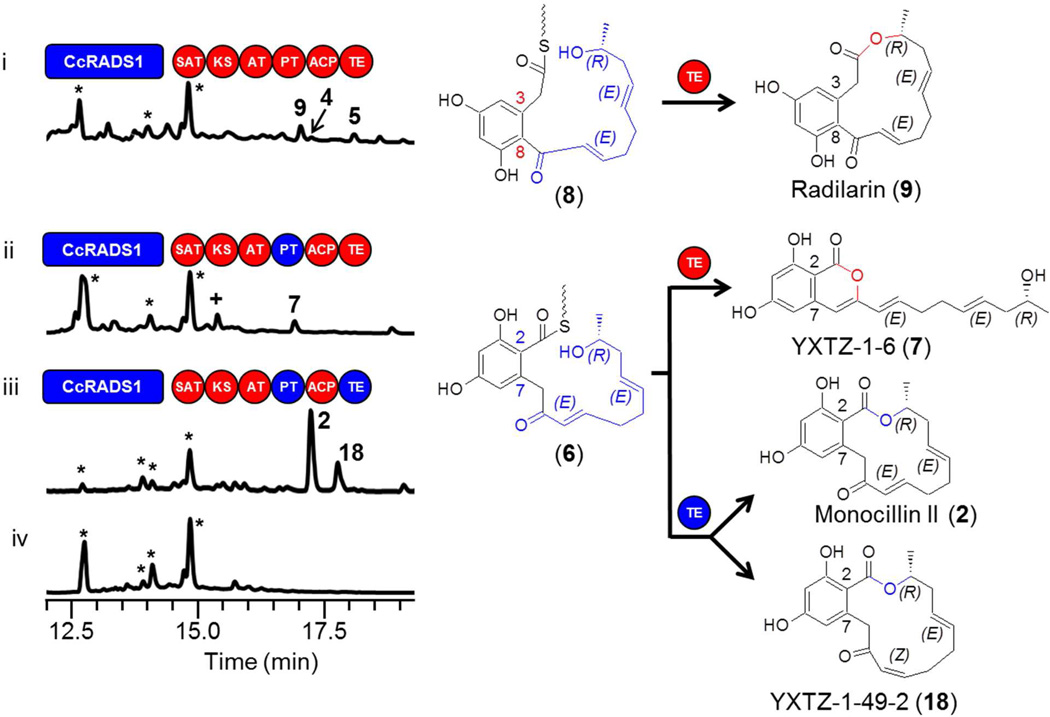

While investigating the substrate preferences and programming rules of these TEs in our in vivo reconstituted systems, we also noticed that the presence of a heterologous TE domain may reveal unexpected product formation in combinatorial contexts. Combining the CcRADS1 hrPKS with the AtCURS2 nrPKS provided small amounts of the 14-membered DAL radilarin (9) and the fatty acyl-derived ADA products 4 and 5 (Fig. 5 trace i, 0.5, 0.1, 0.3 mg/l for 9, 4 and 5, respectively). Replacing the PT domain of AtCURS2 with PTCcRADS2 similarly yielded minor amounts of the isocoumarin 7 (Fig. 5 trace ii, 0.5 mg/l), featuring the engineered C2—C7 first ring and a pentaketide acyl chain. These two experiments indicated that the SAT domain of AtCURS2 is somewhat promiscuous and is able to recognize and transfer the pentaketide product of CcRADS1 onto AtCURS2. In both cases, TEAt-CURS2 appeared permissive to the formation of these minor products. Surprisingly, when TECcRADS2 was introduced into the latter construct, 2 was formed in large amounts (Fig. 5 trace iii, 6 mg/l), with 18 as the minor product (1 mg/ml). 18 features a cis double bound between C10 and C11, likely formed by an endogenous enzyme of the host. Thus, a TE domain with an inbuilt preference for the acyl thioester presented to it by the nrPKS can overrule the expected impediment to product formation caused by the imperfect pairing of the hrPKS and the nrPKS by a mismatched SAT domain.

Figure 5.

TEs may facilitate unexpected biosynthetic interactions. Product profiles of S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA19,41 co-transformed with engineered hrPKS-nrPKS pairs as indicated: (i) YEpCcRADS1 and YEpAtCURS2; (ii) YEpCcRADS1 and YEpAtCURS2-PTCcRADS2; (iii) YEpCcRADS1 and YEpYX49; (iv) no-PKS control. The hrPKS-generated portions of the proposed ACP-bound thioester intermediates are color-coordinated with the synthase. Domains drawn as red circles are derived from AtCURS2, while those in blue are from CcRADS2. *, Yeast metabolites unrelated to the iPKS products. +, Compound decomposed during isolation.

DISCUSSION

Very recently, Yeh et al. replaced the TE domain of an nrPKS responsible for the production of 2,4-dihydroxy-3,5,6-trimethylbenzaldehyde with TE domains from several other nrPKSs, and concluded that the phylogenetic position of the nrPKSs (and by extension, their TE domains) is a good predictor for the success of product formation.44 They posited that close phylogenetic relationship translates to better domain-domain interactions and further, to successful product release in engineered synthases. In contrast, our results emphasize that the shape and size of the polyketide substrate offered to the TE by the rest of the synthase is the crucial determinant for product release. This interpretation is also in agreement with the results of Yeh et al.44 Thus, the relatedness of the product structures is a better predictor of combinatorial success than phylogenetic relationship of the TEs / nrPKSs. This view emphasizes that TE domains are discriminative catalysts, and even more importantly, that they act as decision gates that determine both the final shape of the product and the extent of turnover by nrPKS enzymes. This control role is different from an alreadyrecognized housekeeping role responsible for the restoration of the biosynthetic flux by the removal of stalled, aberrant acyl thioesters, as seen with the noranthrone synthase TE.38

In another very recent set of elegant experiments, Vagstad et al. investigated the effect of altered chain length on the ability of TE/CLC domains to release products derived from completely unreduced poly-β-ketoacyl intermediates.43 They offered a heptaketide chain produced by the purified SAT-KS-AT chassis of the CTB1 nortoralactone synthase to isolated PT, ACP and TE domain sets from other nrPKSs in vitro. Product release by Claisen/Dieckman cyclization, the native mode of the investigated TE domains, was detected to varying degrees with three PT-ACP-TE sets. Not surprisingly, the most efficient combination turned out to be the one where the native substrate of the incoming PT-ACP-TE set was identical to that offered by the heterologous SAT-KS-AT chassis. A PT-ACP-TE set that “expected” a nonaketide was barely functional with the heptaketide substrate. Only TE-independent spontaneous product release was observed with another PT-ACP-TE set that generates a tricyclic product in its native context. Thus, this in vitro reconstituted system supports the requirement of TEs to be presented with thioester intermediates similar to their native substrates, while showed some permissiveness in terms of substrate chain length. Alteration of cyclization modes was not investigated independent of chain length in this study as a factor in TE-catalyzed product release, nor was the production of novel unnatural polyketides detected with these in vitro domain combinations.

The decision gating role of the TE domains, revealed in our study, has significant consequences over and above the perhaps expected lower product yields due to incomplete processing of a foreign substrate. Inappropriate choice of a TE could completely eradicate product formation in an otherwise highly productive chassis, as seen when TECcRADS2 failed to process the carrier protein thioester 3 (compare Fig. 2 trace ii and trace i). Conversely, a judicious choice of a TE may allow the production of a desired hybrid metabolite, as seen when TEAtCURS2, but not TECcRADS2 successfully processed thioester 8 leading to the effective biosynthesis of the novel unnatural product radilarin (9) (Fig. 3 trace ii vs. Fig. 4 trace iii). Finally, a serendipitous choice of a TE may reveal the unexpected productivity of some chassis, as seen when TECcRADS2, but not TEAtCURS2, permitted the high level production of 2 in an “uncoupled” hrPKS-nrPKS pair (Fig. 5 trace iii vs. trace ii). These observations point to the complexity of the decision gating role of the nrPKS TE domains. First, overall product flux is determined by these TEs, similar to the situation in modular PKSs of bacteria where the turnover rate of TE-catalyzed product release regulates extension cycles in “congested” upstream modules.45 Next, the TE domains of the nrPKSs investigated in this study also display context-dependent release mechanisms, yielding macrolactones, carboxylic acids and their esters, and pyrones. Thus, the TE decision gate joins previouslyidentified control points for polyketide assembly on nrPKSs: selection of an appropriate primer unit by the SAT; acyl chain length monitoring and kinetic control of chain extension vs. cyclization by the KS; and regiospecific cyclization by the PT domain.17,38 This ultimate decision gate influences the observable outcome of combinatorial domain swaps, making interpretation of such experiments more complex, and emphasizing that the deduced programming rules for “rational domain heterocombinations”43 are, in fact, context dependent.

CONCLUSIONS

Understanding the inbuilt programming differences of product release from engineered fungal iPKSs is fundamental to guide efforts to generate novel chemical diversity from natural fungal polyketides. By exploiting an array of chimeric iPKS enzyme pairs during the reprogrammed biosynthesis of unnatural benzenediol lactone products, we show that even closely related, orthologous O—C bond-forming TE domains may yield different product release outcomes. Influenced by both the chain lengths and the geometries of the first rings of the polyketide intermediates presented by the chassis of the synthase, these TE domains determine both the shape and the yield of polyketide products, and may obstruct, or conversely, facilitate product formation in an idiosyncratic, context-dependent manner. Thus, TE domains of fungal iPKSs act as non-equivalent decision gates that direct the malleable, reactive intermediates towards defined structural and functional classes of the polyketide space.

Importantly, workers of combinatorial biosynthesis need to be cognizant of the decision gating role of the TE domains of collaborating iPKS pairs, and by extension, other nrPKSs. Thus, it will be necessary to consider both the intrinsic substrate repertoire of the given TE, and the modulation of the product release mode by the incoming polyketide intermediate amongst hydrolysis, pyrone formation, transesterification, and macrolactone formation as demonstrated in this study, and also by Claisen/Dieckmann cyclization as shown by others.43 These factors may complicate engineering approaches for the biosynthesis of a desired “unnatural product”, but may also open additional avenues for the creation of biosynthetic novelty based on fungal nonreduced polyketides.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Culture Conditions

E. coli DH10B and plasmid pJET1.2 (Fermentas) were used for routine cloning and sequencing. The yeast – E. coli shuttle vectors YEpADH2p-FLAG-URA and YEpADH2p-FLAG-TRP with the URA3 or with the TRP1 selectable markers13,19 were used for the expression of hrPKS-nrPKS pairs in Saccha-romyces cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA (MATα ura3-52 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 trp1 pep4::HIS3 prb1 Δ1.6R can1 GAL).41,46 Primers used in this study, and details on the construction of gene variants are described in the SI Materials and Methods. Polyketide production was analyzed in three to five independent transformants for each recombinant yeast strain by small scale fermentation. Fermentations with representative isolates were repeated at least three times to confirm results, and scaled up to 1–5 l to isolate products, as described.13,17

Chemical Characterization of Polyketide Products

Optical rotations were recorded on a Rudolph Autopol IV polarimeter using a 10-cm microcell. Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were acquired with a JASCO J-810 instrument using a path length of 1 cm. 1H, 13C, and 2D NMR (COSY, HSQC, HMBC, ROESY) spectra were obtained in CD3OD or C5D5N on a JEOL ECX-300 spectrometer. ESI-MS data were collected on an Agilent 6130 Single Quad LC-MS. Accurate mass measurements were performed with matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) on a Bruker Ultraflex III MALDI TOF-TOF instrument, or with electrospray ionization (ESI) on a Bruker 9.4 T Fourier transform ion-cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) instrument. Low resolution tandem mass spectra were obtained on a Thermoelectron LCQ instrument, and high resolution MS/MS was performed by FT-ICR using ESI. See SI Methods for details.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (MCB-0948751 to I. M.), the National Institutes of Health (AI065357 to J. Z.), and Utah State University (Seed Program to Advance Research Collaborations, to J. Z.). We are grateful to Professors Nancy A. Da Silva (University of California, Irvine) and Yi Tang (University of California, Los Angeles) for providing the yeast host strain and expression vectors, and to Árpád Somogyi (University of Arizona, Tucson) for the MS/MS spectra and accurate mass measurements.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information.

Additional methods, results, Figures S1-S9, primer list, and spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crawford JM, Townsend CA. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;8:879. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chooi YH, Tang Y. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:9933. doi: 10.1021/jo301592k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt N, Pautz A, Art J, Rauschkolb P, Jung M, Erkel G, Goldring MB, Kleinert H. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;79:722. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elzner S, Schmidt D, Schollmeyer D, Erkel G, Anke T, Kleinert H, Förstermann U, Kunz H. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:924. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santagata S, Xu YM, Wijeratne EM, Kontnik R, Rooney C, Perley CC, Kwon H, Clardy J, Kesari S, Whitesell L, Lindquist S, Gunatilaka AAL. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:340. doi: 10.1021/cb200353m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLellan CA, Turbyville TJ, Wijeratne EMK, Kerschen A, Vierling E, Queitsch C, Whitesell L, Gunatilaka AAL. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:174. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.101808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Workman P, Burrows F, Neckers L, Rosen N. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1113:202. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald E, Workman P, Jones K. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2006;6:1091. doi: 10.2174/156802606777812004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winssinger N, Fontaine JG, Barluenga S. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009;9:1419. doi: 10.2174/156802609789895665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winssinger N, Barluenga S. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2007;2007:22. doi: 10.1039/b610344h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox RJ. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:2010. doi: 10.1039/b704420h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keatinge-Clay AT. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012;29:1050. doi: 10.1039/c2np20019h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, Espinosa-Artiles P, Schubert V, Xu YM, Zhang W, Lin M, Gunatilaka AAL, Süssmuth R, Molnár I. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79:2038. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03334-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foulke-Abel J, Townsend CA. ChemBioChem. 2012;13:1880. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crawford JM, Korman TP, Labonte JW, Vagstad AL, Hill EA, Kamari-Bidkorpeh O, Tsai SC, Townsend CA. Nature. 2009;461:1139. doi: 10.1038/nature08475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas R. ChemBioChem. 2001;2:612. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20010903)2:9<612::AID-CBIC612>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Y, Zhou T, Zhou Z, Su S, Roberts SA, Montfort WR, Zeng J, Chen M, Zhang W, Zhan J, Molnár I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:5398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301201110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang S, Xu Y, Maine EA, Wijeratne EMK, Espinosa-Artiles P, Gunatilaka AAL, Molnár I. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:1328. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou H, Qiao K, Gao Z, Vederas JC, Tang Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:41412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.183574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Xu W, Tang Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:22764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.128504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wijeratne EMK, Paranagama PA, Gunatilaka AAL. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:8439. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhan J. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009;9:1598. doi: 10.2174/156802609789941906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou H, Zhan J, Watanabe K, Xie X, Tang Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800657105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reeves CD, Hu Z, Reid R, Kealey JT. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:5121. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00478-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim YT, Lee YR, Jin J, Han KH, Kim H, Kim JC, Lee T, Yun SH, Lee YW. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;58:1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaffoor I, Brown DW, Plattner R, Proctor RH, Qi W, Trail F. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:1926. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.11.1926-1933.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou H, Gao Z, Qiao K, Wang J, Vederas JC, Tang Y. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:331. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crawford JM, Thomas PM, Scheerer JR, Vagstad AL, Kelleher NL, Townsend CA. Science. 2008;320:243. doi: 10.1126/science.1154711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang M, Zhou H, Wirz M, Tang Y, Boddy CN. Biochem. 2009;48:6288. doi: 10.1021/bi9009049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korman TP, Crawford JM, Labonte JW, Newman AG, Wong J, Townsend CA, Tsai SC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:6246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913531107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Du L, Lou L. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010;27:255. doi: 10.1039/b912037h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vagstad AL, Hill EA, Labonte JW, Townsend CA. Chem. Biol. 2012;19:1525. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujii I, Watanabe A, Sankawa U, Ebizuka Y. Chem. Biol. 2001;8:189. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)90068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaffoor I, Trail F. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:1793. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.3.1793-1799.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck ZQ, Aldrich CC, Magarvey NA, Georg GI, Sherman DH. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13457. doi: 10.1021/bi051140u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kohli RM, Walsh CT, Burkart MD. Nature. 2002;418:658. doi: 10.1038/nature00907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kopp F, Marahiel MA. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007;18:513. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vagstad AL, Bumpus SB, Belecki K, Kelleher NL, Townsend CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6865. doi: 10.1021/ja3016389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu T, Chiang YM, Somoza AD, Oakley BR, Wang CC. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:13314. doi: 10.1021/ja205780g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crawford JM, Vagstad AL, Ehrlich KC, Townsend CA. Bioorg. Chem. 2008;36:16. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma SM, Li JW, Choi JW, Zhou H, Lee KK, Moorthie VA, Xie X, Kealey JT, Da Silva NA, Vederas JC, Tang Y. Science. 2009;326:589. doi: 10.1126/science.1175602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newman AG, Vagstad AL, Belecki K, Scheerer JR, Townsend CA. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:11772. doi: 10.1039/c2cc36010a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vagstad AL, Newman AG, Storm PA, Belecki K, Crawford JM, Townsend CA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:1718. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yeh HH, Chang SL, Chiang YM, Bruno KS, Oakley BR, Wu TK, Wang CC. Org. Lett. 2013;15:756. doi: 10.1021/ol303328t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hong H, Leadlay PF, Staunton J. FEBS J. 2009;276:7057. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee KK, Da Silva NA, Kealey JT. Anal. Biochem. 2009;394:75. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.