Abstract

Objective: Computerized cognitive-bias modification (CBM) protocols are rapidly evolving in experimental medicine yet might best be combined with Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (iCBT). No research to date has evaluated the combined approach in depression. The current randomized controlled trial aimed to evaluate both the independent effects of a CBM protocol targeting imagery and interpretation bias (CBM-I) and the combined effects of CBM-I followed by iCBT. Method: Patients diagnosed with a major depressive episode were randomized to an 11-week intervention (1 week/CBM-I + 10 weeks/iCBT; n = 38) that was delivered via the Internet with no face-to-face patient contact or to a wait-list control (WLC; n = 31). Results: Intent-to-treat marginal models using restricted maximum likelihood estimation demonstrated significant reductions in primary measures of depressive symptoms and distress corresponding to medium-large effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.62–2.40) following CBM-I and the combined (CBM-I + iCBT) intervention. Analyses demonstrated that the change in interpretation bias at least partially mediated the reduction in depression symptoms following CBM-I. Treatment superiority over the WLC was also evident on all outcome measures at both time points (Hedges gs = .59–.98). Significant reductions were also observed following the combined intervention on secondary measures associated with depression: disability, anxiety, and repetitive negative thinking (Cohen’s d = 1.51–2.23). Twenty-seven percent of patients evidenced clinically significant change following CBM-I, and this proportion increased to 65% following the combined intervention. Conclusions: The current study provides encouraging results of the integration of Internet-based technologies into an efficacious and acceptable form of treatment delivery.

Keywords: cognitive-bias modification (CBM), Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (iCBT), major depressive disorder, depression, interpretation bias, mental imagery

Depression is a common, recurrent, and debilitating disorder (Andrews, 2001). Cognitive theories highlight the role of biases in information processing, such as the tendency to preferentially assign negative or threatening appraisals to ambiguous information, in the development and maintenance of the disorder (Rude, Wenzlaff, Gibbs, Vane, & Whitney, 2002). These cognitive biases are a central target of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which is recommended as a first-line treatment for depression (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009). Yet, due to several factors, including the necessity of specialized training of clinicians, long wait lists to access services, and financial barriers, few patients receive CBT (Lovell & Richards, 2000). This has led to increasing calls for the development of novel, accessible, and cost-effective treatments for depression (Simon & Ludman, 2009).

One efficacious, cost-effective, and pragmatic means of increasing patient access to evidence-based treatment is through the use of Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (iCBT) programs (Andrews, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy, & Titov, 2010). CBT explicitly addresses the cognitive biases thought to play a central role in depression through a process of cognitive evaluation and behavioral hypothesis testing in a top-down fashion. However, emerging experimental and translational research has suggested that it may be possible to modify these biases directly (or bottom up) via simple computerized training procedures, known as cognitive-bias modification (CBM). There is mounting evidence that a computerized CBM program targeting interpretation bias (the tendency to interpret ambiguous information negatively; Butler & Mathews, 1983) via mental imagery can significantly reduce symptoms of depression (Blackwell & Holmes, 2010; Holmes, Lang, & Shah, 2009; Lang, Blackwell, Harmer, Davison, & Holmes, 2012). In this training, individuals are repeatedly presented with ambiguous scenarios that are consistently resolved in a positive manner, thus training an automatic bias to positively interpret novel ambiguous information in their day-to-day lives (Holmes, Mathews, Dalgleish, & Mackintosh, 2006; Mathews & Mackintosh, 2000). These findings suggest that imagery-based CBM (CBM-I) could have promise as a stand-alone intervention for depression or alternatively complement traditional psychotherapy. It seems useful to test if the bottom-up approach afforded by CBM could be combined with a top-down approach of CBT, both developed for remote delivery on the Internet. To our knowledge, no research group has integrated the two technologies in order to evaluate this proposal in depression.

The current study reports the results of a CONSORT-compliant randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the efficacy of a brief 7-day Internet-delivered CBM-I intervention followed by a 10-week iCBT program delivered entirely remotely. We sequenced the interventions based on the assumption that CBM-I may provide helpful preparation to optimize engagement with the more challenging iCBT components. We measured change on primary (depression severity and distress) and secondary (disability, anxiety, and repetitive negative thinking) measures in patients diagnosed with a major depressive episode. The treatment package was compared to a wait-list control (WLC), in line with the early stage of this research. We further evaluated whether the change in interpretation bias mediated the reduction in depression symptoms following CBM-I. Finally, we evaluated the acceptability to patients of the Internet-delivered form of CBM-I and the integration with an existing iCBT program. We predicted within-group effects in the intervention group and treatment superiority over the WLC group on all measures.

Method

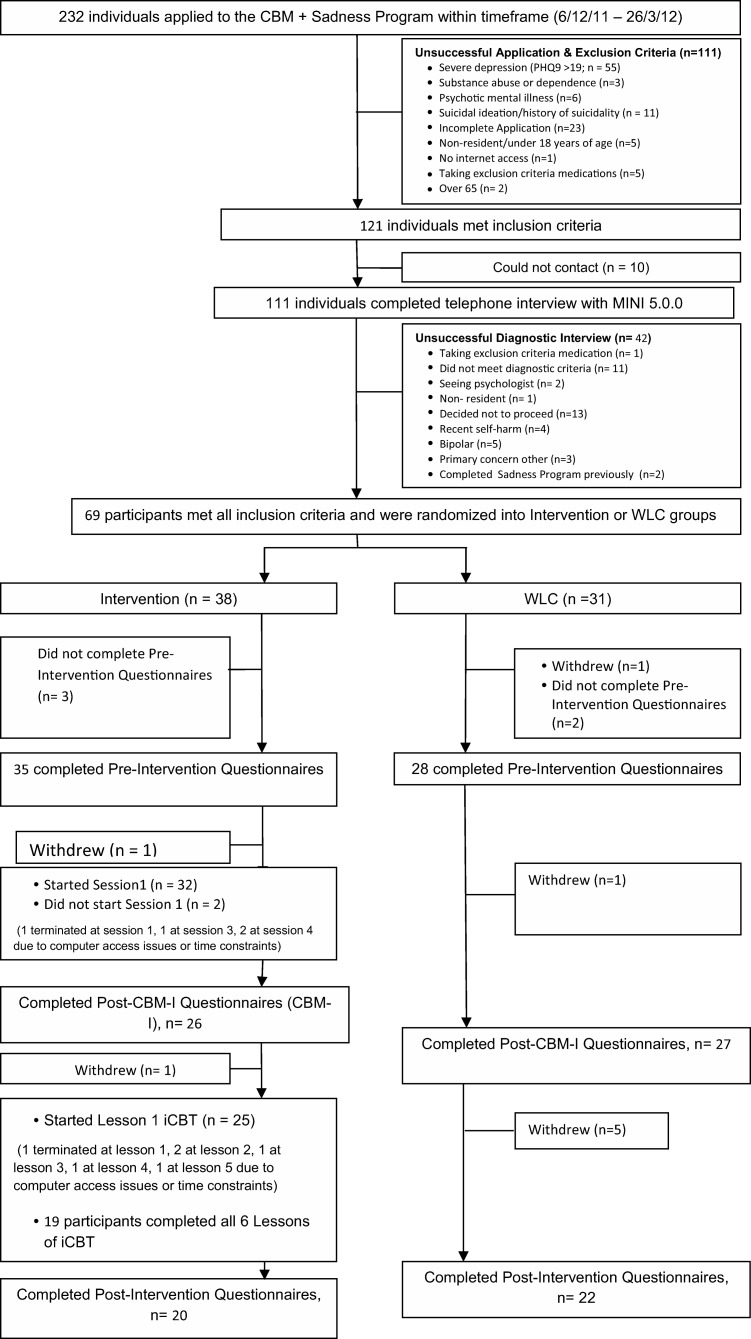

Power calculations were informed by effect size data (Blackwell & Holmes, 2010). Using a conservative estimate of Cohen’s d = 1.00, alpha was set at 0.05 and power at .90. The minimum sample size for each group was identified as 21, but more were recruited to hedge against expected attrition. Participants were recruited via the research arm (virtualclinic.org.au) of the Clinical Research Unit for Anxiety and Depression (CRUfAD), a not-for-profit clinical and research unit in Sydney, Australia. Applicants first completed online screening questionnaires (see the participant flowchart1 in Figure 1). Successful applicants were telephoned for a diagnostic interview using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Version 5.0.0 (MINI; Sheehan et al., 1998).2 The 69 people who completed an electronic informed consent were randomized by an independent person via a true randomization process (www.random.org) to either the intervention (n = 38) or wait-list control (WLC) group (n = 31; see Figure 1). The WLC group completed iCBT after the intervention group had completed all study components. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of St. Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney and the HREC of the University of New South Wales, also in Sydney. The trial was registered as ACTRN12611001221943 and NCT01488058.

Figure 1. Trial flowchart. CBM = cognitive-bias modification; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; MINI 5.0.0 = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Version 5.0.0; WLC = wait-list control; CBM-I = imagery-based CBM; iCBT = Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy.

The Beck Depression Inventory–2nd edition (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) and the nine-item Depression Scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) were the primary outcomes measures of depression severity. The 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10; Kessler et al., 2002) was used to index distress. Interpretation bias was measured with the Ambiguous Scenarios Test–Depression (AST-D; Berna, Lang, Goodwin, & Holmes, 2011) and an electronic version of the Scrambled Sentences Test (SST; Rude et al., 2002). Two versions of the AST-D were presented in counterbalanced order. Secondary outcomes measures included the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule–II (WHODAS-II; Üstün et al., 2010), the State Trait Anxiety Inventory–Trait Version (STAI-T; Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983), and the Repetitive Thinking Questionnaire (RTQ10; McEvoy, Mahoney, & Moulds, 2010). Our Treatment Expectancy and Outcomes Questionnaire (adapted from Devilly & Borkovec, 2000) contained these three questions: “At this point, how logical does the program offered to you seem? (0 = Not at all logical to 4 = Very logical), “At this point, how useful do you think this treatment will be in reducing your depression symptoms?” (0 = Not at all useful to 4 = Very useful), and “Overall, how satisfied are you with your treatment?” (1 = Very dissatisfied to 5 = Very satisfied).

The CBM-I component consisted of seven sessions (20 min each) of imagery-focused CBM-I completed daily over the course of 1 week (see Blackwell & Holmes, 2010, for details and refer to the Figure 1 for compliance). The iCBT component consisted of the Sadness Program, which has been evaluated in three previous trials (see Titov, Andrews, Davies, et al., 2010), and an effectiveness study conducted in primary care (Williams & Andrews, 2013). The program consists of six online lessons representing best practice CBT as well as regular homework assignments and access to supplementary resources (see Titov, Andrews, Davies, et al., 2010, for details). The entire assessment and intervention was conducted online with no face-to-face contact. All patients first completed primary (BDI-II, PHQ9, K10, AST-D, SST) and secondary (WHODAS-II, STAI-T, RTQ10) baseline measures followed by either the 7-day CBM-I component or the wait list. All patients completed the primary measures after the 7-day intervention phase, followed by either the 10-week iCBT component or the wait list. All patients completed the baseline battery of questionnaires (minus the AST-D and SST) after 10 weeks. The WLC group then commenced deferred treatment (iCBT).

Significance testing of group differences regarding demographic data and pretreatment measurements was conducted using analysis of variance and chi-square, where the variables consisted of nominal data. Intent-to-treat marginal models using restricted maximum likelihood estimation were used to account for missing data due to participant dropouts.3 Significant effects were followed up with pairwise contrasts. Effect sizes were calculated between groups (Hedges g) and within groups (Cohen’s d) using the pooled standard deviation. Clinically significant change was defined as high-end state functioning (BDI-II score < 14) combined with a total score reduction greater than the reliable change index of 7.16 (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). PROCESS was used for indirect effects (Hayes, 2012).4

Results

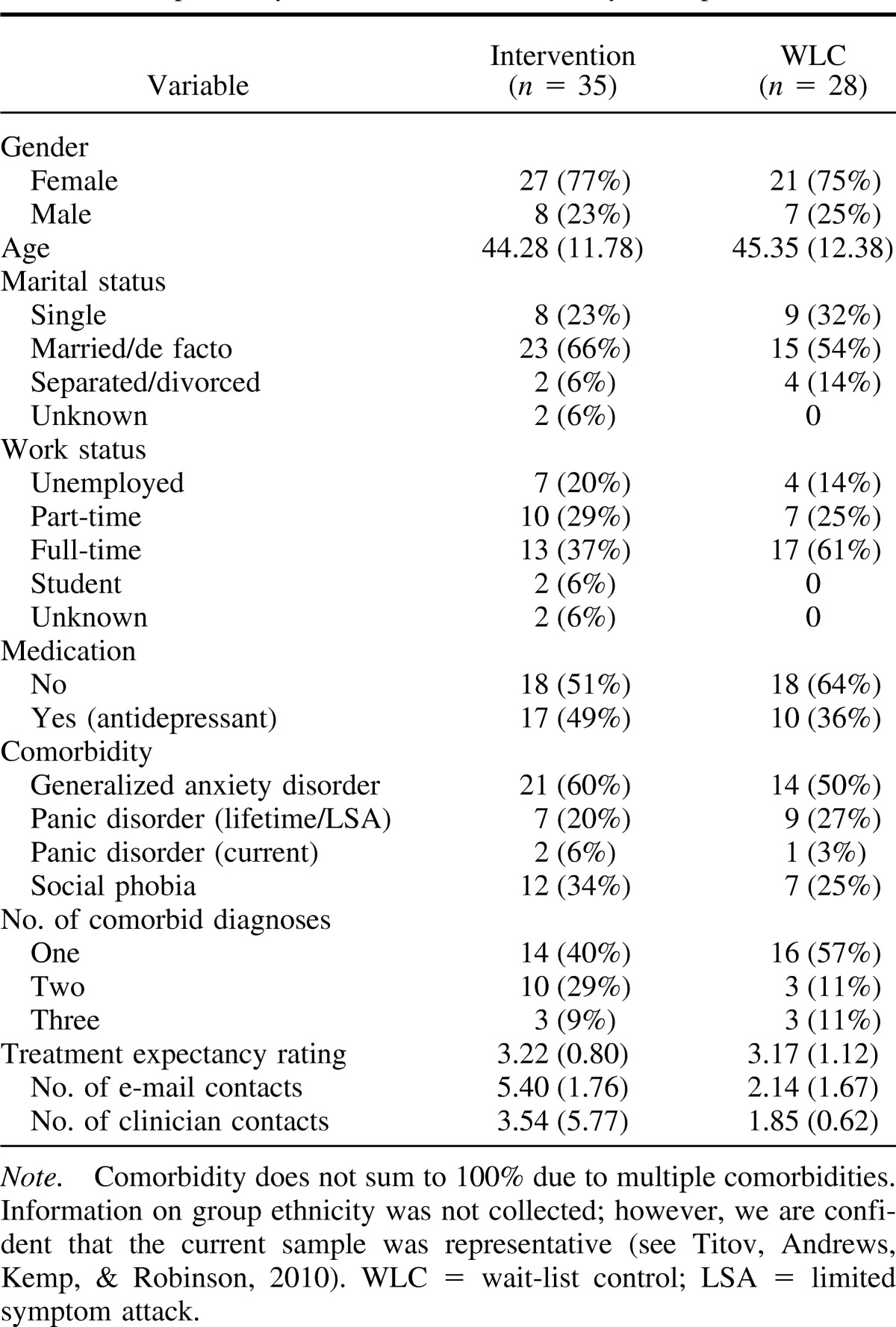

There were no significant group differences in any of the baseline measures (ts < 1.86, ps > .05) or in age, t(61) = 0.35, p > .05; gender, χ2(1) = 1.00, p > .05; or medication use, χ2(2) = 1.09, p > .05 (see Table 1). There were no differences in patients’ ratings of treatment expectations (ts < 1, ps > .05). Although standard e-mail contact did differ, t(61) = 7.44, p < .001, due to technical assistance required in the intervention group, the amount of personal contact with the research team did not vary (p > .05). Marginal models with group as a fixed factor and time as a repeated factor were conducted separately for each of the outcome measures. Results evaluating the independent effects of CBM-I and the combined effects are reported in Table 2.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics, Medication Use, Comorbidity, Treatment Expectancy, and Clinical Contact by Group at Baseline.

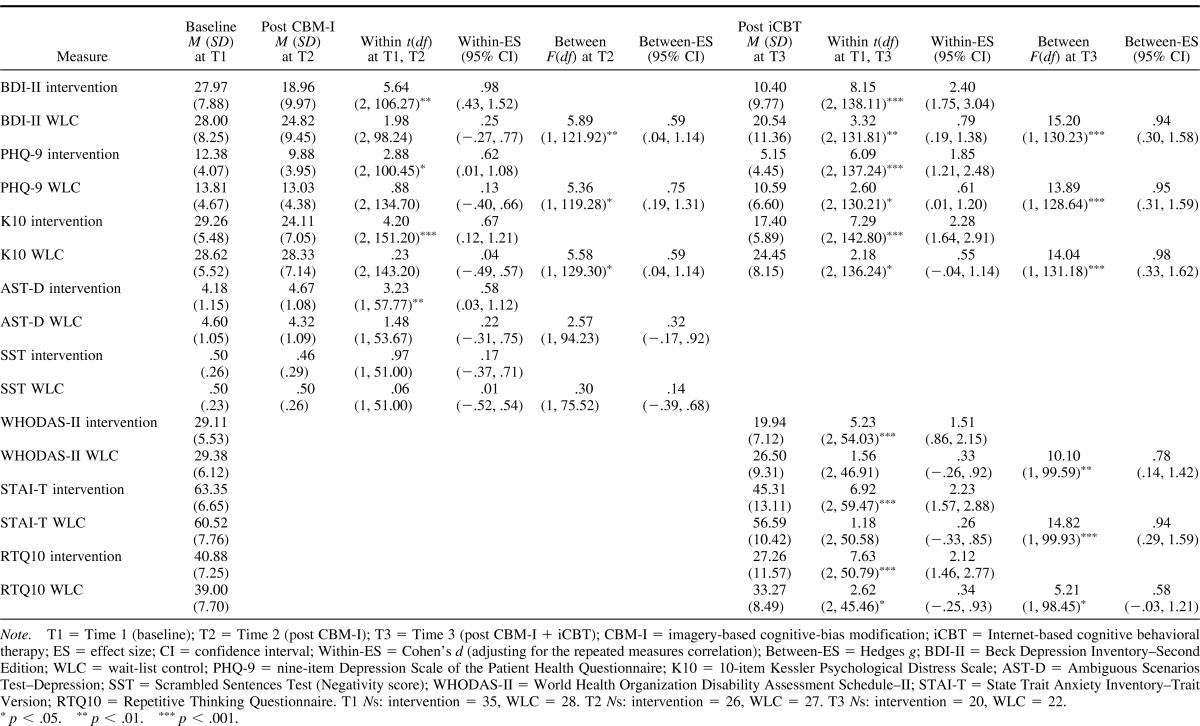

Table 2. Observed Means (and Standard Deviations) for Measures and Within- and Between-Group Effect Sizes Following CBM-I (T2) and CBM-I + iCBT (T3).

Following CBM-I, the reductions in BDI-II, PHQ-9, and K10 scores in the intervention group were all significant and corresponded to medium-large effects. Between-groups superiority of the intervention group was evident on all measures, corresponding to medium effects. Mean AST-D scores did not differ between groups, but the increase in mean scores (more positive interpretations) in the intervention group was significant, corresponding to a medium effect. There was no significant change in the WLC group. There was no main effect or interaction for SST-Negativity scores. Clinically significant change was evident in 27% (n = 7) of the intervention group compared to 0.07% (n = 2) in the WLC group, χ2(1, 53) = 3.57, p = .05. The indirect effect of change in interpretive bias on depression symptoms was evaluated through simple mediation (Model 4; Hayes, 2012) with group as the independent variable, BDI-II change scores (T1, T2) as the dependent variable, and AST-D change scores as the mediating variable. Results of 5,000 bootstrap resamples demonstrated that the total effect was significant (effect = 5.89, SE = 1.99, t = 2.95, p = .004). The direct effect of group on BDI-II was not significant (p = .09), but critically, the indirect effect of AST-D on the change in BDI-II scores was (effect = 2.31, SE = 1.16), 95% CI [0.71, 5.04]. Normal theory tests of the indirect effect also supported the significant indirect effect of AST-D change scores on the dependent variable (effect = 2.31, SE = 1.16., Z = 1.99, p = .04).

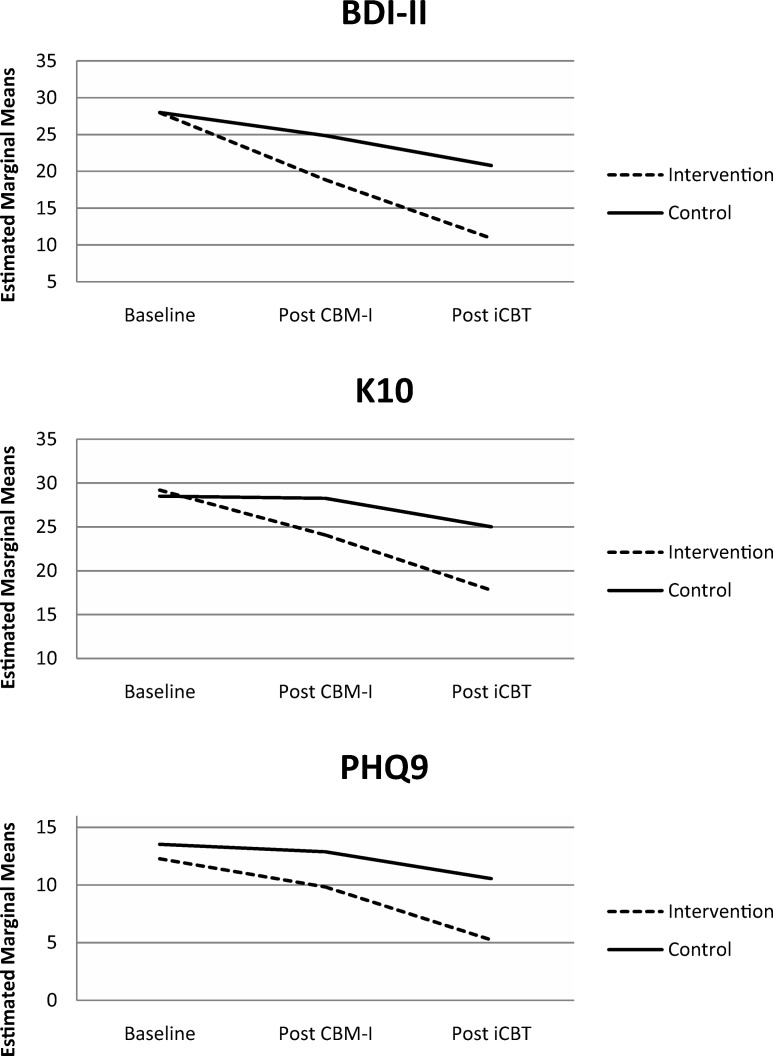

Analyses of the combined intervention demonstrated significant reductions in all primary measures (BDI-II, PHQ-9, K10) in the intervention group, corresponding to large effects (see Table 2 and Figure 2). Significant reductions were also observed in the WLC group corresponding to medium effects, but intervention group superiority was observed for all measures. For WHODAS-II, STAI-T, and RTQ10, all scores were significantly lower in the intervention group relative to the WLC group, corresponding to medium-large effect sizes. Large within-group effects were observed in the intervention group. Significant reductions were also observed in the WLC group, but intervention group superiority was evident on all measures. Sixty-five percent (n = 13) of patients in the intervention group evidenced clinically significant change on the BDI-II compared to 36% (n = 8) in the WLC, χ2(1, 42) = 3.43, p = .06. The majority of patients who completed the combined intervention indicated the instructions were either easy or very easy to follow (77%), indicated that CBM-I was at least moderately logical (88%), and rated the quality of the combined intervention as good or excellent (84%). Mean ratings of confidence in recommending the intervention to a friend with depression (1 = not at all confident to 10 = extremely confident) were 7.77 (SD = 2.10).

Figure 2. Mean reductions on primary measures following imagery-based cognitive-bias modification (CBM-I) and Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (iCBT). BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition; K10 = 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; PHQ-9 = nine-item Depression Scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire.

Discussion

The current RCT represents the first investigation within a clinical trials framework of Internet-delivered CBM for depression targeting interpretation and imagery. The results suggest that Internet-delivered CBM-I for depression can effect rapid symptom reduction over just 1 week, via seven 20-min sessions, and no additional “homework.” Moreover, the effect of the CBM-I intervention on symptoms of depression was at least partially mediated by the trained change in imagery-based interpretive bias (AST-D). Recent work has suggested that repeated practice in generating vivid positive mental imagery, as required in this CBM-I paradigm, could have its therapeutic impact via a number of mechanisms, such as up-regulation of brain areas involved in the generation of positive emotions (Linden et al., 2012), or via increasing optimism (Blackwell et al., 2013). Results also demonstrate the feasibility of integrating CBM into an existing iCBT treatment program for depression.

The combined intervention was effective in reducing depressive symptoms, distress, disability, anxiety, and rumination in patients diagnosed with a major depressive episode. The combined intervention compares favorably to the iCBT component when delivered in isolation. Effect sizes for the Sadness Program range from 1.15 to 1.27 for within-group effects and from .63 to 1.09 for between-groups (WLC) effects (Perini, Titov, & Andrews, 2009; Titov, Andrews, Davies, et al., 2010). Sixty-five percent of patients who completed the combined intervention evidenced clinically significant change on the BDI-II as indexed by established criteria for recovery and reliable change. As a first test of this CBM-I program delivered over the Internet, it is encouraging that the CBM-I intervention was perceived as logical and comprehensible. Despite the obvious pragmatic benefits of Internet-based interventions, patient perceptions of acceptability and adherence will be fundamental to successful implementation.

The current findings need to be considered in light of a number of limitations. In the absence of an active control group, the design of the current study does not allow us to solely attribute clinical change following CBM-I to the intervention. Our research group is currently conducting a second RCT including an active comparator to help address this issue. As a diagnostic interview was not conducted at follow-up, clinical significant change was indexed by self-report measurement. It is important to note that we are unable to establish the temporal precedence of the change in AST-D and depression symptoms; therefore the results of the mediation analysis cannot speak to the issue of causality. Further, the shift in interpretive bias was only evident on the measure that was most similar to the CBM-I training component.

It will be important in future research to dismantle the added impact of CBM-I to the iCBT program and uncover how the two interventions combine to reduce depressive symptoms. For example, it is possible that the initial reduction in symptoms of depression resulting from CBM-I leads to a boost in motivation needed to carry out tasks required in iCBT. Perhaps the trained bias to automatically interpret ambiguity in a positive manner makes it easier to generate alternative thoughts or to envision positive outcomes for the behavioral tasks that form important parts of iCBT. With increasing evidence that cognitive biases are a key target, not only for psychological but also pharmacological interventions for depression (Harmer et al., 2009), investigating mechanisms will have broader relevance. The extent to which these findings are generalizable to other populations and are maintained at follow-up requires further investigation. In summary, the current study provides the first indication of the effectiveness of a combined CBM-I and iCBT intervention in the treatment of major depression and provides encouraging results of the integration of Internet-based technologies into an acceptable form of treatment delivery.

Acknowledgments

Alishia D. Williams is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia Fellowship (630746). Portions of this research were supported by a University of New South Wales Medicine faculty grant awarded to Alishia D. Williams. Emily A. Holmes and Simon E. Blackwell are supported by the Medical Research Council (United Kingdom) intramural program (MC-A060-5PR50) and a grant from the Lupina Foundation. Emily A. Holmes is also supported by a Wellcome Trust Clinical Fellowship (WT088217) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre based at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust, Oxford University. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. Funding to pay the open access publication charges for this article was also provided by the UK Medical Research Council.

Footnotes

If taking medication for anxiety or depression, the dosage must have been stable for at least 1 month and the patient agree not to make changes during the course of the program.

The MINI has been employed in other RCTs of depression treatment with an estimated interclass consistency of .96 when delivered via telephone (see Mohr et al., 2012).

The assumption that data was missing at random was evaluated by using binary logistic regression to predict dropouts (0 = no dropout, 1 = dropout) and by comparing these two groups on baseline measures. No baseline characteristics differed between the two groups or predicted attrition (all ps > .05). As the primary outcomes measures (BDI-II, PHQ-9, K10) were collected at three time points, effects were modeled using an autoregressive covariance structure to account for the correlation between the time points. Effects for the secondary measures were modeled using an unstructured covariance structure. Model fit was determined using Schwarz’s Bayesian information criterion.

This method was chosen over the causal steps approach based on recent research advocating for the use of modern statistical approaches to quantifying intervening variable models. As recommended, particularly for small samples, estimates of indirect effects were generated using bootstrapping analysis (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). In bootstrapping analysis, the most stringent test of an indirect effect (mediation) is if the 95% bias-corrected and -accelerated confidence intervals for the indirect effect do not include the value of 0.

References

- Andrews G. (2001). Should depression be managed as a chronic disease? British Medical Journal, 322, 419–421. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7283.419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Cuijpers P., Craske M. G., McEvoy P., & Titov N. (2010). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: A meta-analysis. PloS One, 5(10), e13196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. T., Steer R. A., & Brown G. K. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory manual (2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Berna C., Lang T. J., Goodwin G. M., & Holmes E. A. (2011). Developing a measure of interpretation bias for depressed mood: An ambiguous scenarios test. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 349–354. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell S. E., & Holmes E. A. (2010). Modifying interpretation and imagination in clinical depression: A single case series using cognitive bias modification. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24, 338–350. doi:10.1002/acp.1680 [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell S. E., Rius-Ottenheim N., Schulte-van Maaren Y. W. M., Carlier I. V. E., Middlekoop V. D., Zitman F. G., et al. Giltay E. J. (2013). Optimism and mental imagery: A possible cognitive marker to promote wellbeing? Psychiatry Research, 206, 56–61. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler G., & Mathews A. (1983). Cognitive processes in anxiety. Advances in Behaviour Research & Therapy, 5, 51–62. doi:10.1016/0146-6402(83)90015-2 [Google Scholar]

- Devilly G. J., & Borkovec T. D. (2000). Psychometric properties of the Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 31, 73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer C. J., O’Sullivan U., Favaron E., Massey-Chase R., Ayres R., Reinecke A., et al. Cowen P. J. (2009). Effect of acute antidepressant administration on negative affective bias in depressed patients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166, 1178–1184. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E. A., Lang T. J., & Shah D. M. (2009). Developing interpretation bias modification as a “cognitive vaccine” for depressed mood: Imagining positive events makes you feel better than thinking about them verbally. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 76–88. doi:10.1037/a0012590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E. A., Mathews A., Dalgleish T., & Mackintosh B. (2006). Positive interpretation training: Effects of mental imagery versus verbal training on positive mood. Behavior Therapy, 37, 237–247. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N. S., & Truax P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 12–19. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Andrews G., Colpe L. J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D. K., Normand S. L., et al. Zaslavsky A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32, 959–976. doi:10.1017/S0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L., & Williams J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T. J., Blackwell S. E., Harmer C. J., Davison P., & Holmes E. A. (2012). Cognitive bias modification using mental imagery for depression: Developing a novel computerized intervention to change negative thinking styles. European Journal of Personality, 26, 145–157. doi:10.1002/per.855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden D. E., Habes I., Johnston S. J., Linden S., Tatineni R., Subramanian L., et al. Goebel R. (2012). Real-time self-regulation of emotion networks in patients with depression. PLoS One, 7(6), e38115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell K., & Richards D. (2000). Multiple access points and levels of entry (MAPLE): Ensuring choice, accessibility and equity for CBT services. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 28, 379–391. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews A., & Mackintosh B. (2000). Induced emotional interpretation bias and anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 602–615. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.109.4.602 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy P. M., Mahoney A. E. J., & Moulds M. L. (2010). Are worry, rumination, and post-event processing one and the same? Development of the Repetitive Thinking Questionnaire. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24, 509–519. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr D. C., Ho J., Duffecy J., Reifler D., Sokol L., Burns M. L., et al. Siddique J. (2012). Effect of telephone-administered vs face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy on adherence to therapy and depression outcomes among primary care patients: A randomized trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 307, 2278–2285. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.5588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. (2009). Depression: Management of depression in primary and secondary care. London, England: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Perini S., Titov N., & Andrews G. (2009). Clinician-assisted Internet-based treatment is effective for depression: A randomized controlled trial. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43, 571–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., & Hayes A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rude S. S., Wenzlaff R. M., Gibbs B., Vane J., & Whitney T. (2002). Negative processing biases predict subsequent depressive symptoms. Cognition & Emotion, 16, 423–440. doi:10.1080/02699930143000554 [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D. V., Lecrubier Y., Sheehan K. H., Amorim P., Janavs J., Weiller E., et al. Dunbar G. C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM–IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59, 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G. E., & Ludman E. J. (2009, August 22). It’s time for disruptive innovation in psychotherapy. Lancet, 374, 594–595. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61415-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C. D., Gorsuch R. L., Lushene R., Vagg P. R., & Jacobs G. A. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Andrews G., Davies M., McIntyre K., Robinson E., & Solley K. (2010). Internet treatment for depression: A randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistance. PLoS One, 5(6), e10939. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Andrews G., Kemp A., & Robinson E. (2010). Characteristics of adults with anxiety or depression treated at an Internet clinic: Comparison with a national survey and an outpatient clinic. PLoS One, 5(5), e10885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Üstün T. B., Chatterji S., Kostanjsek N., Rehm J., Kennedy C., Epping-Jordan J., et al. Pull C. (2010). Developing the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88, 815–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A. D., & Andrews G. (2013). The effectiveness of Internet cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) for depression in primary care: A quality assurance study. PLoS One, 8(2), e57447. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]