Gastric cancer is among the leading causes of cancer death worldwide. Surgery is the only curative modality, but mortality remains high because a significant number of patients have recurrence after complete surgical resection. In this review, we examine the current literature on adjuvant treatment of gastric cancer and discuss the roles of radiation and chemotherapy, particularly in light of new data and their applicability to the Western population.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Adjuvant treatment, Radiation, Chemotherapy

Learning Objectives

Summarize trends of adjuvant treatment in gastric cancer.

Describe the potential role of adjuvant chemotherapy versus radiation in gastric cancer.

Abstract

Gastric cancer is among the leading causes of cancer death worldwide. Surgery is the only curative modality, but mortality remains high because a significant number of patients have recurrence after complete surgical resection. Chemotherapy, radiation, and chemoradiotherapy have all been studied in an attempt to reduce the risk for relapse and improve survival. There is no globally accepted standard of care for resectable gastric cancer, and treatment strategies vary across the world. Postoperative chemoradiation with 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin is most commonly practiced in the United States; however, recent clinical trials from Asia have shown benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy alone and have questioned the role of radiation. In this review, we examine the current literature on adjuvant treatment of gastric cancer and discuss the roles of radiation and chemotherapy, particularly in light of these new data and their applicability to the Western population. We highlight some of the ongoing and planned clinical trials in resectable gastric cancer and identify future directions as well as areas where further research is needed.

Implications for Practice:

Adjuvant treatment in gastric cancer plays a big role after surgical resection in order to decrease tumor reoccurrence and improve overall survival. However, there is no globally accepted standard of care. Adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical resection has shown benefit in several trials. These trials, however, were mostly conducted in Asia and have not been duplicated in the Western hemisphere. Therefore, the adjuvant treatment in the Western population with gastric cancer is somewhat different. Some patients will receive chemotherapy before and after the surgery and others will receive concurrent chemotherapy and radiation after surgery. This article reviews the current data in adjuvant treatment of gastric cancer and will attempt to clarify the current controversy.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. Nearly one million new cases are diagnosed each year, and there is significant geographic variation in incidence and mortality [1]. More than half the cases occur in East Asia, with Korea and Japan having the highest incidence [1]. Western countries have a lower incidence but a higher mortality because most patients in Western countries have advanced disease at presentation. Five-year overall survival (OS) in the United States is only 27% [2] compared with 69% in Japan, where routine screening for gastric cancer is performed and the majority of patients have localized disease at presentation [3, 4].

Complete surgical resection is highly successful in early stage disease, with survival rates exceeding 90% for disease limited to the submucosa [3, 5, 6]. However, outcomes for surgery alone in more advanced disease (extending through the submucosa or with lymph node involvement) are far from satisfactory, largely because of locoregional and systemic recurrences [7]. Over the past two decades, multimodal therapies including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and chemoradiation have been studied to decrease the risk for relapse and improve survival in patients undergoing curative resection; however, there is no globally accepted standard of care and treatment strategies vary by region. Based on the results of the Medical Research Council Adjuvant Gastric Infusional Chemotherapy (MAGIC) trial, perioperative chemotherapy is standard in the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe [8], whereas adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 (an oral fluoropyrimidine) is recommended in Japan [9, 10]. In the United States, postoperative chemoradiotherapy has been the standard of care since the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) 9008/Intergroup (INT) 0116 trial reported a survival advantage of chemoradiotherapy [11]. All approaches have limitations, and the search for safer and more effective therapies continues. Two large phase III clinical trials from Asia have recently demonstrated efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy alone and questioned the utility of postoperative radiation [12, 13]. In this article, we review the current data on adjuvant therapy for gastric cancer and discuss the roles of radiation and chemotherapy in light of these new data, with a focus on the Western population.

Radiotherapy in the Treatment of Resectable Gastric Cancer

Local or regional disease recurs after resection in a significant proportion of those with gastric cancer [7]. To prevent such recurrences, both preoperative and postoperative radiation therapy have been studied. In a three-arm randomized trial comparing surgery alone versus surgery followed by either radiation or chemotherapy, the British Stomach Cancer Group failed to show a survival benefit for either adjuvant radiation or chemotherapy over surgery alone [14]. On the other hand, a Chinese trial reported a significant improvement in 5-year survival with neoadjuvant radiation compared with surgery alone (30% vs. 20%). Significantly fewer local and regional relapses occurred, whereas the incidence of distant metastases was similar between the two groups [15]. Other smaller trials also suggested a benefit of radiation with or without chemotherapy, but high-level evidence supporting adjuvant chemoradiation was lacking until the INT-0116 study was reported [11, 16].

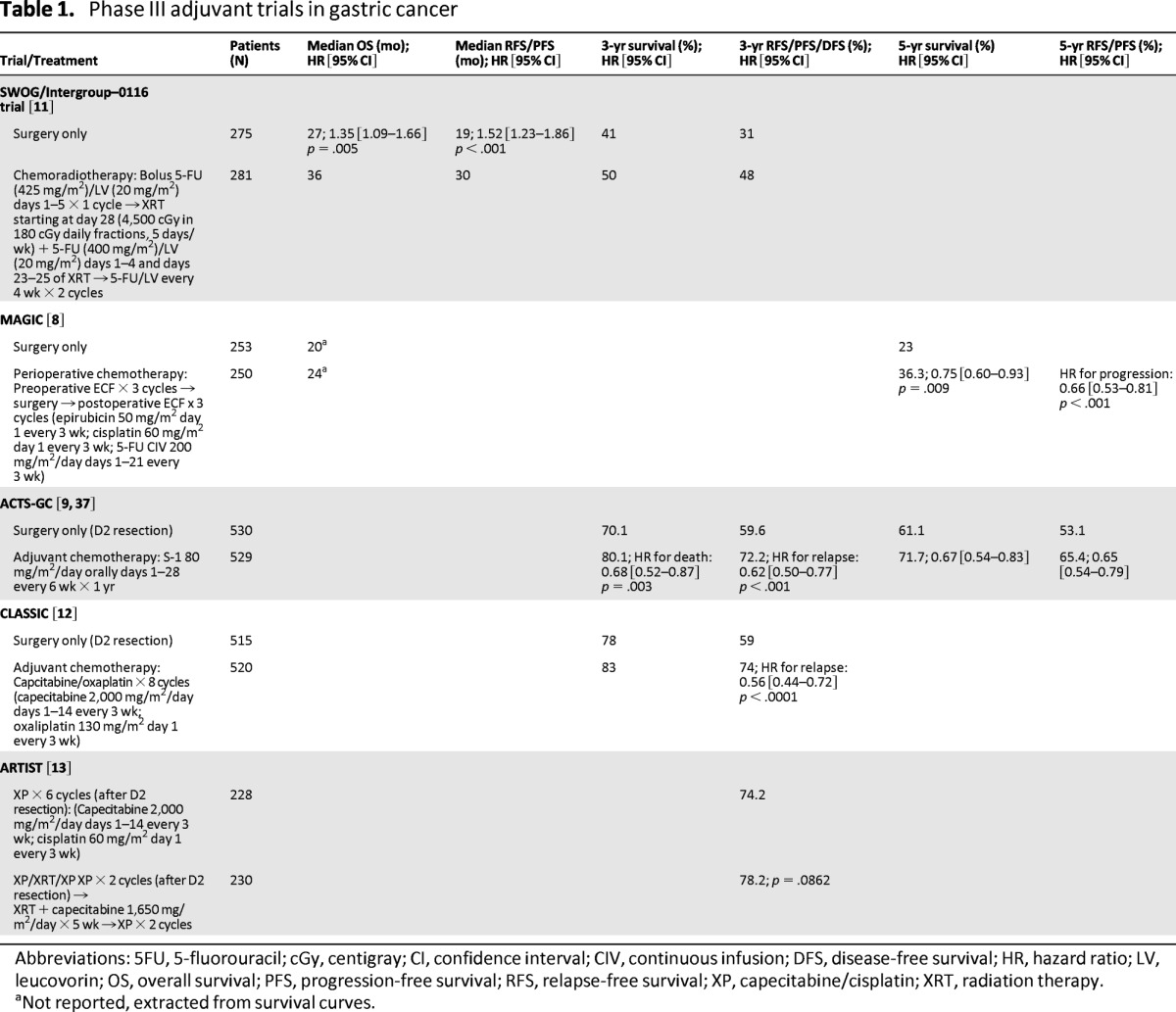

The SWOG/INT-0116 trial was a landmark phase III U.S. study that randomly assigned patients with resected gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma to postoperative chemoradiotherapy versus observation alone [11]. The radiation field encompassed the tumor bed, regional nodes, and 2 centimeters beyond the proximal and distal margins of resection. Treatment was delivered prior to the era of highly conformal therapy with two-dimensional techniques and used bolus 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)/leucovorin rather than continuous infusion. Enrolled patients were at high risk for relapse; more than two thirds had T3 or T4 tumors and nodal involvement was present in 85%. After a median follow-up of 5 years, chemoradiotherapy was associated with significant improvement in median relapse-free survival (RFS) and 3-year RFS (Table 1). More important, the median OS and 3-year survival were significantly better in the chemoradiation group. Local recurrences were also less frequent in the chemoradiotherapy arm (19% vs. 29%). Not surprisingly, chemoradiotherapy was associated with significantly increased toxicity, particularly hematologic and gastrointestinal toxicity. Chemoradiation was completed by 64% of patients, and three patients died as a result of toxic effects. Despite its toxicity, because of a survival advantage, postoperative chemoradiotherapy became the standard of care for high-risk resectable gastric cancer in the United States.

Table 1.

Phase III adjuvant trials in gastric cancer

Abbreviations: 5FU, 5-fluorouracil; cGy, centigray; CI, confidence interval; CIV, continuous infusion; DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; LV, leucovorin; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RFS, relapse-free survival; XP, capecitabine/cisplatin; XRT, radiation therapy.

aNot reported, extracted from survival curves.

Updated results after more than 10 years of follow-up confirmed the persistent benefit of adjuvant chemoradiation [17]. Major endpoints remained virtually identical to the initial analysis and no increase in treatment-related long-term toxicities was noted. With the possible exception of diffuse histology, post hoc subset analyses showed benefit from chemoradiation in all subgroups, including those who underwent D2 dissection [17].

Since the INT-0116 trial, other chemotherapeutic agents with activity in metastatic disease have been studied in combination with postoperative 5-FU/radiotherapy, but outcomes have not improved. The phase III CALGB 80101 trial showed no benefit of adding cisplatin and epirubicin to 5-FU/radiotherapy after curative resection, and 5-FU/leucovorin with radiation remains the standard in the United States [18]. However, bolus 5-FU/leucovorin has been associated with increased toxicity and possibly less efficacy compared with continuous infusion [19]. Therefore, the use of bolus 5-FU has largely been replaced by either continuous infusion 5-FU or capecitabine.

Extent of Lymph Node Dissection

It is noteworthy that D2 lymph node dissection was recommended but not mandatory for enrollment in the INT-0116 trial. Only 10% of patients underwent D2 dissection, 36% underwent D1 dissection, and 54% underwent D0 dissection (incomplete resection of N1 lymph nodes) [11]. Therefore, one of the main criticisms of this study has been that radiotherapy may have only compensated for suboptimal surgery. This is supported by the finding that chemoradiotherapy reduced locoregional recurrences but not distant relapses.

The extent of lymph node dissection in gastric cancer has been a controversial topic. Whereas D2 dissection has long been standard in Japan [10, 20], Western countries have been slow to adopt this approach because no survival advantage has been seen in results of randomized controlled trials. The two largest prospective Western studies that compared D1 with D2 lymph node dissection were conducted by the Dutch Gastric Cancer Group (DGCG) and the UK Medical Research Council (MRC). Both reported significantly higher postoperative morbidity and mortality with D2 dissection and no survival benefit [21–23]. After 15 years of follow-up, however, the Dutch trial did report significantly fewer locoregional recurrences and gastric cancer-related deaths in the D2 arm [24].

Pancreatosplenectomy with D2 resection increases morbidity without improving survival and is no longer recommended. Modified D2 lymphadenectomy, when performed by trained surgical oncologists, has acceptable morbidity and mortality, and it is now considered the standard surgical approach. Extending lymph node dissection beyond D2 to include the para-aortic lymph nodes has not been shown to improve survival and is not recommended.

Importantly, the postoperative mortality for D2 dissection in both studies (∼10%) was much higher than that reported in Japanese trials (<1%) [25]. In the DGCG and MRC trials, increased postoperative mortality likely diluted any survival benefit D2 resection may have provided. Higher morbidity and mortality rates in these trials were attributed to surgical inexperience and outcomes of pancreatosplenectomy, a procedure that was performed routinely with D2 dissection [22]. Pancreatosplenectomy with D2 resection increases morbidity without improving survival and is no longer recommended [26, 27]. Modified D2 lymphadenectomy, when performed by trained surgical oncologists, has acceptable rates of morbidity and mortality, and it is now considered the standard surgical approach [24, 28–31]. Extending lymph node dissection beyond D2 to include the para-aortic lymph nodes has not been shown to improve survival and is not recommended [32]. D2 resection should only be performed by surgeons well trained in the procedure.

The question then arises: Does radiation benefit patients who undergo D2 lymphadenectomy? In the INT-0116 trial, 90% of patients did not undergo D2 lymphadenectomy; additionally, chemoradiation may have only compensated for suboptimal surgery by decreasing locoregional recurrences. Indeed, the investigators subsequently reported that they were able to code D-level by the Japanese general rules and determine the likelihood of undissected regional nodal disease by the Maruyama program, so that they could define the sum of these estimates as the Maruyama index (MI) of unresected disease [33]. They prospectively captured complete surgical information for 553 trial participants and found MI to be an independent prognostic predictor of survival. Theoretically, these locoregional relapses could have been prevented by doing a more extended lymph node dissection during the original procedure. Exploratory subgroup analysis of the INT-0116 10-year follow-up demonstrated a benefit of chemoradiotherapy irrespective of the D-level of dissection; however, as acknowledged by the authors, the number of patients who underwent D2 lymphadenectomy (N = 54) was small and definitive conclusions cannot be made because of a lack of statistical power and the post hoc nature of this analysis [17]. Additionally, in the updated analysis, the authors report that MI serves as a quantitative estimate of the adequacy of nodal surgery in an individual patient. Patients with MI more than 5 had significantly improved outcomes with chemoradiotherapy.

A number of other studies have investigated radiation alone versus observation in patients who have undergone D2 resection, but results have been mixed and definite conclusions cannot be made because most studies were small, underpowered, nonrandomized, observational, or retrospective in nature [34, 35].

Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Resectable Gastric Cancer

Adjuvant chemotherapy has been shown to improve survival in many types of cancer. It has also been studied for treatment of resectable gastric cancer, but trials in the United States have been limited because of the small number of patients. Additionally, most of these studies were performed at a time when D2 resection was not considered standard. A meta-analysis of 17 trials using individual patient data by the Global Advanced/Adjuvant Stomach Tumor Research International Collaboration (GASTRIC) Group showed a modest but statistically significant survival benefit of 5-FU-based postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy (hazard ratio, 0.82; p < .001) compared with surgery alone [36].

MAGIC was the first well-powered prospective study to demonstrate conclusively a survival benefit of chemotherapy in the Western population [8]. In this study, 503 patients with gastric (74%), gastroesophageal, or distal esophageal adenocarcinoma were randomly assigned to surgery with or without perioperative chemotherapy. Three cycles of epirubicin, cisplatin, and continuous infusion fluorouracil were administered before surgery and three cycles were administered after surgery. After a median follow-up of 4 years, the perioperative-chemotherapy group had significantly improved progression-free survival and OS compared with those who underwent surgery alone (Table 1). Five-year survival was 36% in the perioperative-chemotherapy arm versus 23% in the surgery-alone arm. Tumors were smaller in the chemotherapy group, but rates of R0 resection were similar between the two arms. Toxicity was not trivial; only 42% of patients assigned to perioperative chemotherapy completed all six planned cycles. Benefit was seen with chemotherapy irrespective of site of primary tumor, and perioperative chemotherapy became the standard of care in the United Kingdom and in most of Europe. Approximately 40% of patients in the MAGIC trial underwent D2 lymphadenectomy, and although chemotherapy was likely beneficial in patients who underwent D2 resection, the trial was not designed to answer this question.

The pivotal Japanese ACTS-GC study evaluated postoperative S-1 (an oral fluoropyrimidine with 5-FU prodrug and two modulators of 5-FU metabolism) in patients who underwent D2 resection and reported a survival advantage [9]. Patients were randomly assigned to either 1 year of postoperative S-1 chemotherapy or surgery alone. This trial was stopped early when the first interim analysis demonstrated a significantly higher survival in the S-1 group (Table 1). Three-year OS (80.1% vs. 70.1%) and RFS were also higher in the S-1 group (72.2% vs. 59.6%). OS and RFS benefit were confirmed at 5-year follow-up [37]. Despite promising results, the data are not applicable to most Western countries because of significant differences in the pharmacokinetics of this drug between Asian and Western populations and because of a lack of data showing benefit of S-1 over conventional chemotherapy in the West [38, 39].

More recently, another Asian trial, the Capecitabine and Oxaliplatin Adjuvant Study in Stomach Cancer (CLASSIC) study, addressed the question of adjuvant chemotherapy following D2 resection [12]. Patients with stage II-IIIB gastric cancer were randomly assigned to either chemotherapy or observation following D2 gastrectomy (Table 1). Three-year disease-free survival (DFS), a surrogate for OS [40], was the primary endpoint, and OS was a secondary endpoint. The trial was stopped early when the first planned interim analysis showed a significant improvement in DFS. After a median follow-up of 34 months, the chemotherapy group had improved 3-year DFS irrespective of disease stage. Thus far, 3-year survival also seems to favor the chemotherapy group. Predictably, the chemotherapy arm had more toxicity; oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy occurred in 56% of patients (2% had grade 3/4). Two thirds of patients assigned to chemotherapy were able to complete all eight cycles. Survival data from CLASSIC are eagerly awaited.

The 3-year OS rate in the CLASSIC study was remarkably higher than the rate in the INT-0116 or MAGIC trials (78% in CLASSIC vs. 30%–40% in INT-0116 and MAGIC), even in the surgery-only arm of the trial [8, 11]. Notably, only 44% of patients in CLASSIC had T3 or higher tumors compared with 68% in INT-0116 and 64% in MAGIC; however, node-positive disease was more common (89% vs. 85% vs. 73%, respectively). With some differences, the survival data from CLASSIC are comparable to the ACTS-GC study, in which patients also underwent D2 resection [9, 41]. It is possible that improved outcomes in the latter two trials are a result of D2 gastrectomy, but because both of these studies were conducted in Asia, results could also reflect differences in tumor biology, location, and surgical expertise.

Is Chemoradiation Better Than Chemotherapy Alone?

Chemoradiation is known to improve survival, based on the results of the INT-0116 trial, but many questions remain. Can improved conformality with modern radiation therapy, planning, and delivery techniques translate into better outcomes and better toxicity profiles [42–44]? Is chemoradiation better than chemotherapy alone?

Chemotherapy has been directly compared with chemoradiation in patients who underwent D2 resection, but until recently, trials were small, underpowered, or failed to accrue enough patients. Recently Lee et al. reported a phase III trial comparing postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy in patients who had undergone D2 resection, the Adjuvant Chemoradiation Therapy in Stomach Cancer (ARTIST) trial [13]. Although survival data are not available, after a median follow-up of 53 months, there was no difference in the estimated 3-year DFS between the two arms (Table 1). In a subgroup analysis of 396 patients with pathologic lymph node involvement, 3-year DFS was prolonged in the chemoradiotherapy arm compared with the chemotherapy arm (77.5% vs. 72.3%; p = .0365). Statistical significance persisted on multivariate analysis even after adjusting for stage. Survival data were not reported because only 108 patients had died at the time of analysis. No difference in the pattern of relapse (locoregional or distant) was noted between the two arms. Planned therapy was completed by 75% of patients in both arms. A subsequent trial to evaluate chemotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy in patients with lymph node-positive disease is planned (ARTIST-II).

Discussion: Is Radiation Really Necessary?

From the above discussion, it is clear that although there are data to support a number of adjuvant therapeutic approaches, including perioperative chemotherapy, postoperative chemotherapy, and chemoradiotherapy, it remains a challenge to choose the best oncologic strategy. Based on results of the MAGIC, ACTS-GC, and CLASSIC trials and the GASTRIC meta-analysis, it is safe to say that chemotherapy has a role in adjuvant treatment of gastric cancer even in the era of D2 resections. Defining the role of radiation is more complex.

Significant toxicity with chemoradiation, as seen in the INT-0116 trial, is a real concern. Grade 3 or higher hematologic and gastrointestinal toxicity occurred in 54% and 33% patients, respectively, and 17% of patients discontinued treatment because of toxic effects. Radiation oncologists are cognizant of the large volumes of gastrointestinal mucosa within the irradiated field. In the multi-institutional INT-0116 study, treatment fields had to be approved by the radiation-oncology coordinator prior to treatment. Up to 35% of treatment plans were found to contain major or minor deviations from the protocol. Subsequently, consensus guidelines were published to review important anatomic issues to be considered to ensure that radiation oncologists understood the location of the intended targets [45, 46]. Current studies are exploring the benefits of transcending the two-dimensional techniques used in the INT-0116 study in favor of three-dimensional conformal and intensity-modulated radiation therapy [47, 48]. These techniques rely on computed tomography (CT)-based treatment planning to maximize dose to the intended regions and minimize dose to the surrounding normal tissues. With modern technology, radiation oncologists can obtain images of patients prior to each daily fraction of treatment using a process called image-guided radiation therapy, a potentially desirable option given the propensity for organ peristalsis and filling, as well as respiratory-associated motion. Another concern in the INT-0116 trial was a nonsignificant increase in secondary malignancies seen in the chemoradiation arm [17]. Even with improvements in the ability to target the intended tissues, there remains the question whether this will lead to improved outcome for patients receiving adjuvant chemoradiation.

Postoperative chemoradiation was established as the standard of care for resected gastric cancer in the United States at a time when D2 lymphadenectomy was not routinely performed. Now that European and American guidelines recommend spleen-preserving D2 resection [49, 50], the role of radiation needs to be reevaluated. Patterns of relapse after gastrectomy differ based on the extent of lymph node dissection [7]. Local relapses are uncommon in Asian studies, in which D2 resections are performed routinely. Local recurrence developed in only 2.8% of patients in the surgery-alone arm of the Japanese ACTS-GC trial compared with 29% in the INT-0116 trial. Only 10% of patients underwent D2 lymphadenectomy in INT-0116. As discussed later, although this could reflect differences in biology of the disease, it is also likely the result of more extensive lymph node dissection. In the INT-0116 study, chemoradiation decreased locoregional recurrences but had no impact on distant relapses. Chemotherapy without radiation, on the other hand, decreased both local and distant recurrences in the MAGIC, ACTS-GC, and CLASSIC trials. Thus, radiation seems to be most important for controlling local recurrences in patients undergoing suboptimal surgery. Radiation may not be as beneficial for patients undergoing D2 resection, who are already at low risk for local relapse. Indirect supportive evidence comes from retrospective comparisons of Dutch studies, which showed that postoperative chemoradiation reduced local recurrences in patients who underwent D1 resection but not in those who underwent D2 resection [51].

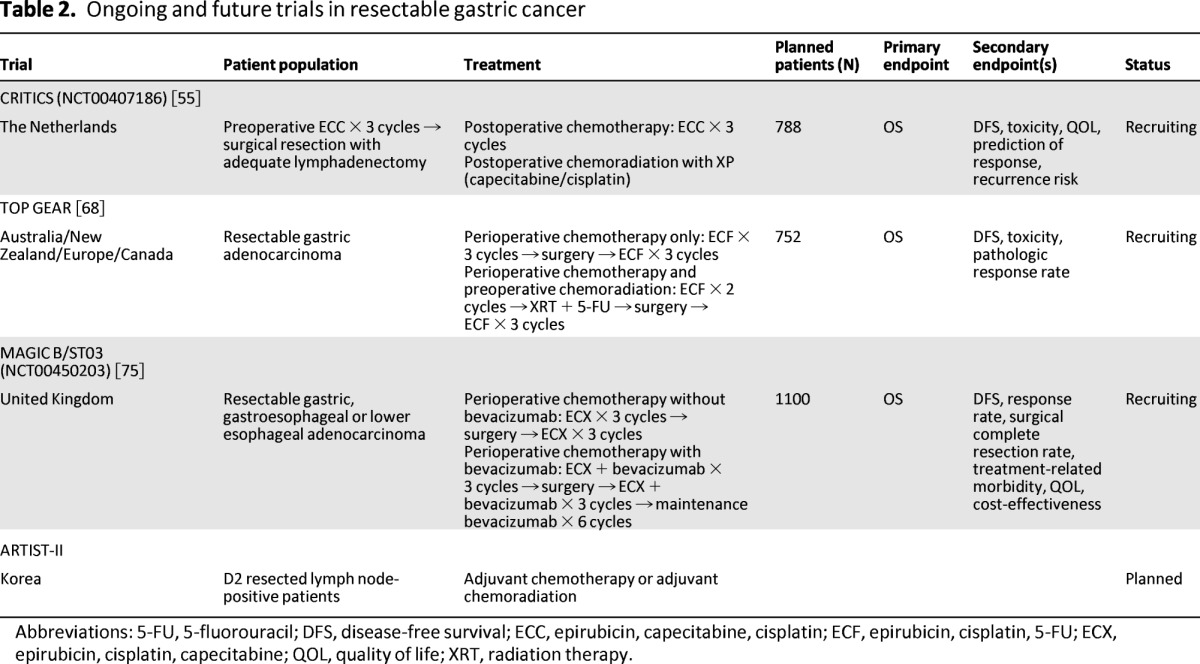

A direct comparison of chemotherapy versus chemoradiation in patients who underwent D2 resection is provided only by the ARTIST trial, which was discussed in the previous section. The trial failed to show that the addition of radiation to postoperative chemotherapy improved DFS. Furthermore, there was no difference in the pattern of relapse between the two arms, suggesting that the addition of radiation to chemotherapy may not benefit all patients undergoing D2 lymphadenectomy. On subgroup analysis, chemoradiation did seem to improve DFS in patients with lymph node involvement. This needs to be evaluated further in a randomized prospective fashion, as is planned for the ARTIST-II trial (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ongoing and future trials in resectable gastric cancer

Abbreviations: 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; DFS, disease-free survival; ECC, epirubicin, capecitabine, cisplatin; ECF, epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU; ECX, epirubicin, cisplatin, capecitabine; QOL, quality of life; XRT, radiation therapy.

Before extrapolating these data to Western populations, one should be mindful that the ACTS-GC, CLASSIC, and ARTIST trials were all conducted in East Asia. D2 lymphadenectomy is routinely performed in Asia and reported outcomes have consistently been superior to those seen in the West. Whereas this may reflect more extensive surgical experience in the East, there are also some key differences in the biology of tumors between the East and West [52]. Proximal tumors and diffuse histology, both associated with worse prognosis, are more frequent in the West [53]. Interestingly, in the subset analysis of INT-0116, patients with diffuse histology did not benefit from adjuvant chemoradiation [11]. Tumors are usually advanced at diagnosis in Western countries, whereas most tumors are localized at diagnosis in Eastern countries because more people undergo screening [54]. Moreover, patients in the West are often older at diagnosis and have more comorbidity (e.g., obesity) than their Eastern counterparts [53]. These factors limit the generalizability of studies conducted in one part of the world, and the question remains: Can we replicate outcomes from CLASSIC and ARTIST trials in the Western population? The ChemoRadiotherapy after Induction chemoTherapy In Cancer of the Stomach (CRITICS) trial is currently accruing participants and will likely be helpful in this regard [55]. In this Dutch trial, all patients will receive three cycles of preoperative chemotherapy with epirubicin, capecitabine, and cisplatin, followed by adequate resection. Patients will then be randomly assigned to postoperative chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy alone (Table 2), thereby assessing the role of radiation with perioperative chemotherapy in adequately resected Western patients.

Is Adjuvant Radiation Needed for Esophageal/Gastroesophageal Junction Tumors?

From a therapeutic standpoint, it is important to distinguish gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) tumors from gastric cancer. In prospective trials, GEJ tumors have been included in both the upper tract (esophagus) and lower tract (gastric) studies. For patients with GEJ tumors who undergo upfront surgery, adjuvant chemoradiation is appropriate based on the INT-0116 trial. Approximately 20% of patients enrolled in this study had GEJ tumors [11]. Other options are perioperative chemotherapy based on the MAGIC trial, which included GEJ tumors (11%) [8]. However, GEJ tumors resemble distal esophageal cancers and for the most part are treated in a similar manner. The recent seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging is indicative of this pattern, as GEJ tumors are staged as esophageal cancer in these guidelines and not as gastric cancer.

Randomized adjuvant trials are lacking for esophageal/GEJ tumors because of the abundance of data in the neoadjuvant setting, leading to some form of induction therapy. Based on several prospective studies and a meta-analysis, trimodality therapy using neoadjuvant chemoradiation is recommended [56–59]. The largest trial to show a benefit of neoadjuvant chemoradiation is the CROSS study [57]. In this study, 366 patients (11% with GEJ adenocarcinoma) were randomly assigned to receive neoadjuvant chemoradiation with carboplatin and paclitaxel followed by surgery or surgery alone. The preoperative chemoradiotherapy arm had significantly better OS (49.4 vs. 24 months; p = .003) and DFS (not reached vs. 24.2 months; p < .001).

The only phase III trial comparing neoadjuvant chemoradiation with chemotherapy alone was conducted in Germany [60]. This trial was exclusively for patients with GEJ tumors. Results showed a higher complete pathologic response (15.6% vs. 2.0%) and a trend toward improved 3-year survival for the neoadjuvant chemoradiation arm (47% vs. 28%; p = .07).

To date, no randomized trial has shown a survival advantage of adjuvant treatment in patients with esophageal cancer who undergo surgery without neoadjuvant therapy. However, few retrospective and uncontrolled trials suggest potential benefit from adjuvant therapy [61].

Future Directions

Methods of identifying those with gastric cancer who are more likely to benefit from neoadjuvant therapy are needed. No such biomarkers are currently available; however, data are emerging that metabolic information from positron emission tomography (PET)-CT may be prognostic and predictive. The German Metabolic response evalUatioN for Individualisation of neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in oesOphageal and oesophagogastric adeNocarcinoma (MUNICON) trial used PET-CT to predict response after two weeks of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in GEJ tumors [62]. Nonresponders were referred for earlier surgery and thus were spared the toxicity of inactive therapy without compromising survival. Similar response-directed approaches need to be evaluated in resectable gastric cancer. GEJ tumors are distinct from gastric cancer and are now appropriately included in the category of esophageal cancers in the updated AJCC staging system. Although most GEJ tumors are fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid, up to 30% of gastric cancers are non-avid and cannot be visualized by FDG-PET [63]. Use of alternative radioisotopes such as fluorothymidine may improve sensitivity of PET-CT in gastric cancer [64].

Another important issue to be addressed is the optimal timing of chemoradiotherapy with respect to surgery. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy improves survival in esophageal and GEJ cancer [57]. Despite the concern for overtreatment in some patients, it has the potential advantages of downsizing tumors, making them more resectable, and providing an in vitro assessment of response to therapy. Theoretically, this could allow modifications of the treatment plan in the event of poor response. So far, preoperative chemoradiotherapy in gastric cancer has only been tested in small phase II studies [65–67]. A large phase II/III trial is currently underway, the Trial of Preoperative Therapy for Gastric and Esophagogastric Junction Adenocarcinoma (TOPGEAR), in which patients are being randomly assigned to either preoperative chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy (Table 2) [68].

Targeted therapies have shown promise in metastatic gastric cancer, but further studies are needed to incorporate them into the adjuvant setting. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is overexpressed in a significant proportion of gastric and GEJ tumors, but the anti-EGFR antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab failed to improve outcomes in unselected patients with advanced disease. The Erbitux in Combination With Xeloda and Cisplatin in Advanced Esophago-gastric Cancer (EXPAND) trial did not show a benefit of adding cetuximab to first-line chemotherapy in advanced gastric and GEJ cancers [69], and the addition of panitumumab to chemotherapy in the REAL3 trial was actually associated with worse survival [70]. Hence, there is a lack of enthusiasm for pursuing the use of anti-EGFR antibodies in the adjuvant setting. Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) also failed to improve OS when added to chemotherapy in the multinational phase III AVAGAST trial [71]. However, on preplanned subgroup analysis, there was a survival benefit in patients from North and South America, and the ongoing MAGIC-B trial in the United Kingdom is comparing perioperative chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with resectable gastric cancer (Table 2) [72].

EGFR is overexpressed in a significant proportion of gastric and GEJ tumors, but the anti-EGFR antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab failed to improve outcomes in unselected patients with advanced disease. The EXPAND trial did not show a benefit of adding cetuximab to first-line chemotherapy in advanced gastric and GEJ cancers, and the addition of panitumumab to chemotherapy in the REAL3 trial was actually associated with worse survival.

A major advance in the treatment of metastatic gastric cancer has been the discovery of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2/neu) overexpression in almost 20% of patients with gastric cancer. The combination of chemotherapy and trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody against HER-2, resulted in a significant improvement in OS in patients with HER-2-positive metastatic gastric and GEJ cancer [73]. The ongoing phase II TOXAG study is evaluating safety and efficacy of combining trastuzumab with postoperative chemoradiation in HER-2-positive gastric or GEJ cancer. Lapatinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor that inhibits both EGFR and HER-2, is also being studied with chemotherapy in metastatic gastric cancer in the Lapatinib Optimization Study in HER-2 Positive Gastric Cancer (LOGiC) trial [74]. If activity is confirmed, adjuvant lapatinib will be studied in gastric cancer in the second randomization of the MAGIC-B trial [72].

Conclusion

In summary, over the last two decades, several advances have been made in the treatment of gastric cancer. The roles of radiation and chemotherapy are constantly evolving and we now have high-level evidence for a variety of treatment options for resectable gastric cancer. Combined modality therapy offers the best chance for cure of localized disease, and all cases should be approached in a multidisciplinary manner.

Whereas postoperative chemotherapy remains standard in the East, the choice of adjuvant therapy in Western patients depends on whether the patient is seen before or after surgery, and the extent of lymph node dissection, if seen after the surgery. Patients with gastric cancer seen before surgery have the choice of perioperative chemotherapy or upfront surgery followed by postoperative adjuvant therapy. Patients seen after less than D2 resection with no preoperative therapy should be offered postoperative chemoradiotherapy rather than chemotherapy alone because they have a significant potential for unresected regional nodal disease, as measured by the Maruyama index. Those who undergo complete resection with D2 lymphadenectomy without prior therapy can be offered either postoperative chemoradiation or oxaliplatin/capecitabine-based chemotherapy without radiation. Patients with lymph node involvement may benefit from radiation even after D2 resection, based on the ARTIST trial. For patients with GEJ tumors, we would recommend a trimodality approach with neoadjuvant chemoradiation, based on randomized trials. Perioperative chemotherapy with epirubicin, cisplatin, and continuous infusion fluorouracil is also reasonable for those with GEJ cancer and high clinical suspicion of metastatic disease. Patients with GEJ tumors who undergo surgery first can be offered adjuvant chemoradiation, based on the INT-0116 study. Our recommendations are in line with the most recently updated National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for adjuvant therapy of gastric cancer in the United States, which have incorporated postoperative chemotherapy alone as an option for patients undergoing complete resection with D2 lymphadenectomy [50]. One must bear in mind that this recommendation is based on data from the ARTIST and CLASSIC trials, which are preliminary, and longer follow-up is needed to confirm that survival data parallel DFS. Additionally, further studies are still needed to replicate findings reported from Asia in the West, as there are some key differences in the biology and behavior of tumors between the two regions. Future studies should be aimed at identifying predictive biomarkers, delineating the optimal timing and sequence of chemotherapy and radiation with respect to surgery, and exploring the role of biologics in the adjuvant treatment of gastric cancer.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Richard Kim, Noman Ashraf, Sarah Hoffe

Provision of study material or patients: Richard Kim, Noman Ashraf

Collection and/or assembly of data: Richard Kim, Noman Ashraf

Data analysis and interpretation: Richard Kim, Noman Ashraf, Sarah Hoffe

Manuscript writing: Richard Kim, Noman Ashraf, Sarah Hoffe

Final approval of manuscript: Richard Kim, Noman Ashraf

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Section Editors: Richard Goldberg: Bayer, Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi (C/A); Bayer, Sanofi (RF); Patrick Johnston: Almac Diagnostics (E); Chugai Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Sanofi, Roche (H); AstraZeneca, Amgen (RF); Almac Diagnostics, Fusion Antibodies (O); Peter O'Dwyer: Tetralogic Pharmaceuticals, PrECOG, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Topotarget (C/A); Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Methylgene, Novartis, Genentech, Ardea, Exelixis, FibroGen, AstraZeneca, Incyte, ArQule, GlaxoSmithKline (RF); Genentech, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer (H); Tetralogic Pharmaceuticals (O)

Reviewer “A”: Taiho (H)

Reviewer “B”: Genentech (H, C/A); Sanofi (RF)

Reviewer “C”: Lilly/Imclone (C/A); Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, Bayer (RF)

Reviewer “D”: None

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, Isobe Y, et al. Gastric cancer treated in 2002 in Japan: 2009 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0163-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoue M, Tsugane S. Epidemiology of gastric cancer in Japan. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:419–424. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.029330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green PH, O'Toole KM, Slonim D, et al. Increasing incidence and excellent survival of patients with early gastric cancer: Experience in a United States medical center. Am J Med. 1988;85:658–661. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(88)80238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cenitagoya GF, Bergh CK, Klinger-Roitman J. A prospective study of gastric cancer. ‘Real’ 5-year survival rates and mortality rates in a country with high incidence. Dig Surg. 1998;15:317–322. doi: 10.1159/000018645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gunderson LL. Gastric cancer–patterns of relapse after surgical resection. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2002;12:150–161. doi: 10.1053/srao.2002.30817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1810–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3) Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–123. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, et al. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725–730. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bang YJ, Kim YW, Yang HK, et al. Adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (CLASSIC): A phase 3 open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:315–321. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61873-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J, Lim do H, Kim S, et al. Phase III trial comparing capecitabine plus cisplatin versus capecitabine plus cisplatin with concurrent capecitabine radiotherapy in completely resected gastric cancer with D2 lymph node dissection: The ARTIST trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:268–273. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallissey MT, Dunn JA, Ward LC, et al. The second British Stomach Cancer Group trial of adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy in resectable gastric cancer: Five-year follow-up. Lancet. 1994;343:1309–1312. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92464-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang ZX, Gu XZ, Yin WB, et al. Randomized clinical trial on the combination of preoperative irradiation and surgery in the treatment of adenocarcinoma of gastric cardia (AGC)–report on 370 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:929–934. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill PG, Jamieson GG, Denham J, et al. Treatment of adenocarcinoma of the cardia with synchronous chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1020–1023. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smalley SR, Benedetti JK, Haller DG, et al. Updated analysis of SWOG-Directed Intergroup Study 0116: A phase III trial of adjuvant radiochemotherapy versus observation after curative gastric cancer resection. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2327–2333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.7136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuchs CS, Tepper JE, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Postoperative adjuvant chemoradiation for gastric or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma using epirubicin, cisplatin, and infusional (CI) 5-FU (ECF) before and after CI 5-FU and radiotherapy (CRT) compared with bolus 5-FU/LV before and after CRT: Intergroup trial CALGB 80101. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl) Abstract 4003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Meta-analysis Group in Cancer. Efficacy of intravenous continuous infusion of fluorouracil compared with bolus administration in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:301–308. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kajitani T. The general rules for the gastric cancer study in surgery and pathology. Part I. Clinical classification. Jpn J Surg. 1981;11:127–139. doi: 10.1007/BF02468883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuschieri A, Weeden S, Fielding J, et al. Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: Long-term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial. Surgical Co-operative Group Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1522–1530. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartgrink HH, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, et al. Extended lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: Who may benefit? Final results of the randomized Dutch gastric cancer group trial J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2069–2077. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonenkamp JJ, Hermans J, Sasako M, et al. Extended lymph-node dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:908–914. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903253401202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, et al. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:439–449. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70070-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sano T, Sasako M, Yamamoto S, et al. Gastric cancer surgery: Morbidity and mortality results from a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing D2 and extended para-aortic lymphadenectomy–Japan Clinical Oncology Group study 9501. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2767–2773. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kodera Y, Yamamura Y, Shimizu Y, et al. Lack of benefit of combined pancreaticosplenectomy in D2 resection for proximal-third gastric carcinoma. World J Surg. 1997;21:622–627. doi: 10.1007/s002689900283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitamura K, Nishida S, Ichikawa D, et al. No survival benefit from combined pancreaticosplenectomy and total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 1999;86:119–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Degiuli M, Sasako M, Ponti A. Morbidity and mortality in the Italian Gastric Cancer Study Group randomized clinical trial of D1 versus D2 resection for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:643–649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degiuli M, Sasako M, Calgaro M, et al. Morbidity and mortality after D1 and D2 gastrectomy for cancer: Interim analysis of the Italian Gastric Cancer Study Group (IGCSG) randomised surgical trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:303–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ott K, Lordick F, Blank S, et al. Gastric cancer: Surgery in 2011. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:743–758. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0738-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okines A, Verheij M, Allum W, et al. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v50–54. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasako M, Sano T, Yamamoto S, et al. D2 lymphadenectomy alone or with para-aortic nodal dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:453–462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hundahl SA, Macdonald JS, Benedetti J, et al. Surgical treatment variation in a prospective, randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy in gastric cancer: The effect of undertreatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:278–286. doi: 10.1007/BF02573066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leong CN, Chung HT, Lee KM, et al. Outcomes of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy after a radical gastrectomy and a D2 node dissection for gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer J. 2008;14:269–275. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318178d23a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim S, Lim DH, Lee J, et al. An observational study suggesting clinical benefit for adjuvant postoperative chemoradiation in a population of over 500 cases after gastric resection with D2 nodal dissection for adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:1279–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.GASTRIC Group. Paoletti X, Oba K, et al. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:1729–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sasako M, Sakuramoto S, Katai H, et al. Five-year outcomes of a randomized phase III trial comparing adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 versus surgery alone in stage II or III gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4387–4393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ajani JA, Faust J, Ikeda K, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic study of S-1 plus cisplatin in patients with advanced gastric carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6957–6965. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ajani JA, Rodriguez W, Bodoky G, et al. Multicenter phase III comparison of cisplatin/S-1 with cisplatin/infusional fluorouracil in advanced gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma study: The FLAGS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1547–1553. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rougier P, Sakamoto J. Surrogate endpoints for overall survival in resectable gastric cancer and in advanced gastric carcinoma: Analysis of individual data from the GASTRIC collaboration. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(suppl 5):v10–v18. (Abstract O-0012) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshikawa T, Sasako M. Gastrointestinal cancer: Adjuvant chemotherapy after D2 gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:192–194. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ringash J, Perkins G, Brierley J, et al. IMRT for adjuvant radiation in gastric cancer: A preferred plan? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung HT, Lee B, Park E, et al. Can all centers plan intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) effectively? An external audit of dosimetric comparisons between three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy and IMRT for adjuvant chemoradiation for gastric cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1167–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ringash J, Khaksart SJ, Oza A, et al. Post-operative radiochemotherapy for gastric cancer: Adoption and adaptation. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2005;17:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smalley SR, Gunderson L, Tepper J, et al. Gastric surgical adjuvant radiotherapy consensus report: Rationale and treatment implementation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:283–293. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tepper JE, Gunderson LL. Radiation treatment parameters in the adjuvant postoperative therapy of gastric cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2002;12:187–195. doi: 10.1053/srao.2002.30827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taremi M, Ringash J, Dawson LA. Upper abdominal malignancies: Intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Front Radiat Ther Oncol. 2007;40:272–288. doi: 10.1159/000106041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minn AY, Hsu A, La T, et al. Comparison of intensity-modulated radiotherapy and 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy as adjuvant therapy for gastric cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:3943–3952. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson C, Cunningham D, Oliveira J. Gastric cancer: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(Suppl 4):34–36. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Gastric Cancer. Version 2.2012. [Accessed February 18, 2013]. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp.

- 51.Dikken JL, Jansen EP, Cats A, et al. Impact of the extent of surgery and postoperative chemoradiotherapy on recurrence patterns in gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2430–2436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bickenbach K, Strong VE. Comparisons of gastric cancer treatments: East vs. West J Gastric Cancer. 2012;12:55–62. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2012.12.2.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strong VE, Song KY, Park CH, et al. Comparison of gastric cancer survival following R0 resection in the United States and Korea using an internationally validated nomogram. Ann Surg. 2010;251:640–646. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d3d29b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noguchi Y, Yoshikawa T, Tsuburaya A, et al. Is gastric carcinoma different between Japan and the United States? Cancer. 2000;89:2237–2246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dikken JL, van Sandick JW, Maurits Swellengrebel HA, et al. Neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery and chemotherapy or by surgery and chemoradiotherapy for patients with resectable gastric cancer (CRITICS) BMC Cancer. 2011;11:329. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, SMithers BM, et al. Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: An updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:681–692. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschott JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2074–2084. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tepper J, Krasna MJ, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Phase III trial of trimodality therapy with cisplatin, fluorouracil, radiotherapy, and surgery compared with surgery alone for esophageal cancer: CALGB 9781. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1086–1092. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walsh TN, Noonan N, Hollywood D, et al. A comparison of multimodal therapy and surgery for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:462–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stahl M, Walz MK, Stuschke M, et al. Phase III comparison of preoperative chemotherapy compared with chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:851–856. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Armanios M, Xu R, Forastiere AA, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for resected adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, gastro-esophageal junction, and cardia: Phase II trial (E8296) of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4495–4499. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lordick F, Ott K, Krause BJ, et al. PET to assess early metabolic response and to guide treatment of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction: The MUNICON phase II trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:797–805. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ott K, Herrmann K, Krause BJ, et al. The value of PET imaging in patients with localized gastroesophageal cancer. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2008;2:287–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Herrmann K, Ott K, Buck AK, et al. Imaging gastric cancer with PET and the radiotracers 18F-FLT and 18F-FDG: A comparative analysis. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1945–1950. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.044867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ajani JA, Mansfield PF, Janjan N, et al. Multi-institutional trial of preoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with potentially resectable gastric carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2774–2780. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chakravarty T, Crane CH, Ajani JA, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy as preoperative treatment for localized gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rivera F, Galán M, Tabernero J, et al. Phase II trial of preoperative irinotecan-cisplatin followed by concurrent irinotecan-cisplatin and radiotherapy for resectable locally advanced gastric and esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:1430–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leong T. TOPGEAR: Trial of Preoperative Therapy for Gastric and Esophagogastric Junction Adenocarcinoma. A randomised phase II/III trial of preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus preoperative chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer. [Accessed August 5, 2012]; Available at: http://www.australiancancertrials.gov.au/search-clinical-trials/search-results/clinical-trials-details.aspx?TrialID=83497&ds=1. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lordick F, Bodoky G, Chung H-C, et al. Cetuximab in combination with capecitabine and cisplatin as first-line treatment in advanced gastric cancer: Randomized controlled phase III EXPAND study. Paper presented at ESMO Congress; September 30, 2012; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Waddell TS, Chau I, Barbachano Y, et al. A randomized multicenter trial of epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine (EOC) plus panitumumab in advanced esophagogastric cancer (REAL3) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl):LBA4000. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Van Cutsem E, de Haas S, Kang YK, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3968–3976. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smyth EC, Langley RE, Stenning SP, et al. ST03: A randomized trial of perioperative epirubicin, cisplatin plus capecitabine (ECX) with or without bevacizumab (B) in patients (pts) with operable gastric, oesophagogastric junction (OGJ) or lower oesophageal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl):TPS4156. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): A phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.LOGiC - Lapatinib Optimization Study in ErbB2 (HER2) Positive Gastric Cancer: A Phase III Global, Blinded Study Designed to Evaluate Clinical Endpoints and Safety of Chemotherapy Plus Lapatinib. [Accessed July 26, 2013]. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00680901.