Abstract

Objectives. We examined whether characteristics of local health departments (LHD) and their geographic region were associated with using Facebook and Twitter. We also examined the number of tweets per month for Twitter accounts as an indicator of social media use by LHDs.

Methods. In 2012, we searched for Facebook and Twitter accounts for 2565 LHDs nationwide, and collected adoption date and number of connections for each account. Number of tweets sent indicated LHD use of social media. LHDs were classified as innovators, early adopters, or nonadopters. Characteristics of LHDs were compared across adoption categories, and we examined geographic characteristics, connections, and use.

Results. Twenty-four percent of LHDs had Facebook, 8% had Twitter, and 7% had both. LHDs serving larger populations were more likely to be innovators, tweeted more often, and had more social media connections. Frequency of tweeting was not associated with adoption category. There were differences in adoption across geographic regions, with western states more likely to be innovators. Innovation was also higher in states where the state health department adopted social media.

Conclusions. Social media has the potential to aid LHDs in disseminating information across the public health system. More evidence is needed to develop best practices for this emerging tool.

Local health departments (LHDs) are charged with assuring their constituents receive 10 essential public health services.1 Among these services is Essential Service #3 (ES3): inform, educate, and empower people about health issues.1 The Public Health Accreditation Board has included communication with constituents about public health issues and health risks in a recently developed set of standards required of LHDs seeking accreditation.2 As of 2004, only 61% of LHDs were adequately addressing ES3.3

One new communication tool that may aid LHDs in educating and informing their constituents and meeting accreditation standards is social media. Web-based social media sites, such as Facebook and Twitter, can facilitate direct, one-to-many communication with a large audience at little to no cost.4,5 Facebook accounts can be liked, and Twitter accounts can be followed by other users, including the general public, allowing individuals or organizations to receive and spread information posted by a source. A recent survey indicated that 65% of online adults in the United States, or half of all US adults, use social media.6 Facebook and Twitter are the most widely used social media platforms7; worldwide more than 845 million people use Facebook, whereas 140 million people are Twitter users.8 Each minute, 695 000 Facebook statuses are updated, and 98 000 tweets are sent.9

In the United States, social media is used by many segments of the population. Although overall social media use among adults with Internet access is associated with age, it is independent of educational attainment, race/ethnicity, and health care access.10 Likewise, there are no significant differences in Twitter use by education or income; however, the use of Twitter is significantly higher among Black non-Hispanic Internet users (28%) compared with non-Hispanic White (12%) or Hispanic Internet users (14%).11 Twitter use is also significantly higher in young adults compared with older age groups and in urban and suburban locations compared with rural locations.

Use of social media is emerging as a popular way to seek health information for the general public.12,13 For adult Internet users, the Internet is a primary source of health information, second only to health care providers; 80% of US Internet users (or 59% of US adults) have looked online for health information.14,15 Of adult social media users, 23% report following their friends’ personal health experiences or updates, 17% have used social media to remember or memorialize people with a specific health condition, and 15% have obtained health information from social media sites.15

Social media platforms are also increasingly used by health care providers and public health organizations and practitioners to share information with each other during training16,17 and practice,18 and to reach consumers with health information.4,19–21 The World Health Organization has Facebook and Twitter accounts, as do the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and numerous health-related schools and departments, scientists, and health-focused news outlets.20 CDC has developed an online toolkit to aid public health practitioners in using social media to disseminate information and foster partnerships with consumers.5 Advocates of social media use in the health community believe social media outlets provide a place for dialogue with consumers,21 and a mechanism for real-time surveillance22 and rapid dissemination of time-sensitive health information.20,23 Challenges identified by health professionals include a lack of understanding of social media23 and the volume of information available online, which can confuse consumers.20

Despite numerous barriers that often hinder the adoption of new technology in government organizations,4 studies indicate a majority of state health departments (60%–82%) are using at least 1 social media application.24,25 Those health departments using social media report using it daily to disseminate information on healthy behaviors and health conditions.25 In addition, in studies surveying a sample of LHDs nationwide, up to 30.9% reported having a Facebook page, whereas up to 47.0% reported using Twitter.26,27

The adoption of Facebook and Twitter across the public health system constitutes a natural experiment providing insight into how technological innovations spread across this system. Given the potential of social media to reach a large segment of the adult population, many of whom are actively seeking health information online, it is important to better understand the adoption and use of this new tool by public health practitioners. To this end, we were the first that we know of to examine the adoption and use of Facebook and Twitter across all LHDs nationwide. Specifically, we examined whether characteristics of an LHD, and the state and region where it is located, were associated with adoption of social media. We also examined the number of followers or likes for each health department with a Facebook or Twitter account and whether followers and likes were associated with LHD characteristics. Finally, we examined the number of tweets per month for Twitter accounts as a general indicator of social media use by LHDs.

METHODS

We conducted Web searches between December 2011 and July 2012 for Facebook and Twitter accounts for each of 2565 LHDs included in the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) directory.28 When an account was identified, we collected the direct link to the account (URL address), the date the LHD joined Facebook or Twitter, and the number of likes or followers of the account. Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations theory29 characterizes adopters of new technology in 5 types: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards:

Innovators constitute about 2.5% of adopters and are the first to adopt a new technology. They take risks, have some knowledge about technology, and typically have financial resources. Innovators are not necessarily well respected by others in a system, but they play an important role by bringing in new technologies.

Early adopters are the next 13.5% to adopt. They tend to be more integrated into a system and are typically opinion leaders. Early adopters are often sought out as change agents.

Early majority are just ahead of the average member of a system in adopting new ideas. They constitute 34% of system members and are critical in connecting the network.

Late majority adopters make up 34% of the system. They often adopt out of necessity or as a result of peer pressure. They tend to be skeptical of new innovations and often do not have financial resources to recover if the innovation is not successful.

Laggards are the last to adopt and make up the remaining 16%. Many are isolated in their social system and are not leaders; they also tend to lack financial resources.

Making the assumption that most LHDs will eventually adopt social media, we categorized LHDs as innovators (first 2.5%), early adopter or early majority (next 47.5%), and nonadopters of Facebook and Twitter based on their adoption status and date. We also collected the total number of tweets disseminated by each LHD as of July 2012 and computed the average number of tweets per month for each LHD as a measure of social media use.

LHD characteristics from the 2010 NACCHO Profile of Local Health Departments Study (Profile) were used to examine and compare characteristics of LHDs in light of their social media adoption status. There was mixed evidence regarding LHD characteristics associated with performance of ES3; a 2006 study found that health departments serving larger populations with more spending and staffing (full-time employees) per capita were more likely to perform this service.30 However, a follow-up study in 2010 found no significant relationships between performing ES3 and LHD population size or per capita full-time equivalent (FTE) employees and spending, but did find that having a top executive with a master’s degree as their highest degree was negatively associated with ES3 performance.31

Social media adoption and use may have some cost associated with it in terms of time to setup and maintaining social media accounts.4 In light of this and previous findings, we hypothesized that health departments in larger jurisdictions with more staffing and spending per capita would adopt social media earlier and use it more. We also hypothesized that LHDs with public information specialists (PISs) and highly trained top executives would adopt social media earlier and use it more than would LHDs without these specific staff. Because these characteristics were all related to LHD size and capacity, we examined associations among the variables to determine whether they captured unique information. The only strong association was between FTE per capita and spending per capita (r = 0.7; P < .001); FTE per capita was therefore dropped from analyses.

The Profile data included all of the responders to the 2010 survey, which was 82% of all LHDs (n = 2107).26 To determine whether nonresponse was associated with social media adoption, we conducted a χ2 analysis comparing the proportion of LHDs with Facebook and Twitter who were responders or nonresponders to the Profile study. There was a significant association between Profile study participation status and having a Facebook page (χ2[1] = 25.0; P < .05) or a Twitter account (χ2[1] = 16.2; P < .05). Standardized residuals indicated that nonresponders to the Profile study were significantly less likely than expected to have a Facebook page or Twitter account. Nonresponders to the Profile study tended to be LHDs serving smaller populations; for example, the response rate for LHDs serving less than 25 000 constituents was 73%, whereas the response rate for LHDs serving 1 million or more constituents was 95%.26

State-specific rates of ever accessing the Internet, using Facebook or other social networking sites, and using Twitter or another similar service, were obtained from the 2010 Pew Internet & American Life Project Health Tracking survey.32 Finally, social media adoption by each state health department as of 2012 was adopted from a previous study.33

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare means for characteristics measured on a continuous scale across LHDs that were innovators, early adopters or majority, and nonadopters of Facebook and Twitter. Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to identify which means were significantly different from one another following each significant ANOVA result. Significant associations between adoption and categorical characteristics of LHDs were identified through χ2 analysis; standardized residuals were examined for all significant χ2 results to determine where the observed proportion of LHDs in a given category deviated significantly from the expected value. The t-test and partial correlation analysis were used to examine differences in the number of friends and followers by LHD characteristics. Statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS version 18.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY); maps were developed using ArcMap version 10 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, CA).

RESULTS

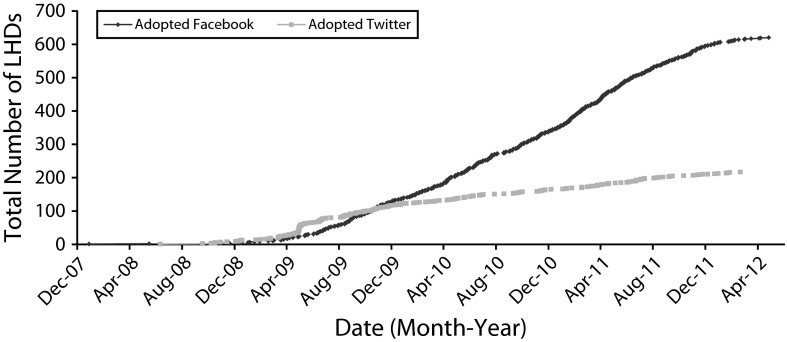

LHDs began to join Facebook in 2007 and Twitter in 2008. As of early 2012, 24% (n = 618) of LHDs had a Facebook account, and 8% (n = 217) had a Twitter account; 7% of LHDs had both (n = 176). Adoption of both platforms was steady over time, with the exception of a small jump in Twitter adoption in mid-2009 (Figure 1). On average, LHDs with Twitter had tweeted 13.7 times per month (SD = 18.2) since adoption.

FIGURE 1—

Adoption of Twitter and Facebook over time among local health departments: United States, 2012.

Geography and Social Media Adoption

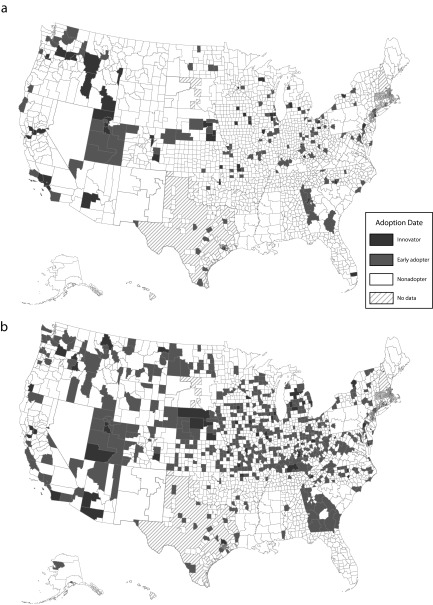

Adoption category was significantly associated with US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) region34 for both Twitter (χ2[18] = 78.7; P < .01) and Facebook (χ2[18] = 225.9; P < .01; Table 1). For both Twitter and Facebook, region 1 in the northeastern states (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont) had significantly fewer than expected innovators and early adopter or majority LHDs, whereas region 9 (Arizona, California, Hawaii, and Nevada) in the western states had significantly more innovators than expected. There were several other significant deviations from expected values; Figure 2 and Table 1 show the geographic distribution of innovators, early adopter or majority, and nonadopting LHDs for Twitter and Facebook. Areas shown as “No Data” on the map in Figure 2 are not covered by an LHD. Some of these areas may be covered by health offices that are affiliated with state health departments, local boards of health, or other agencies.

TABLE 1—

State and Regional Characteristics of Local Health Departments Adopting Twitter and Facebook: United States, 2012

| Variable | Innovator, No. (%) or Mean ±SE | Early Adopter/Majority, No. (%) or Mean ±SE | Nonadopters, No. (%) or Mean ±SE | χ2 | F | df | P |

| LHD is in HHS region | |||||||

| 1 (CT, ME, MA, NH, RI, VT) | 3a (0.7) | 10a (2.3) | 421 (97.0) | 78.7 | 18 | < .01 | |

| 2 (NJ, NY) | 3 (1.8) | 8 (4.9) | 153 (93.3) | ||||

| 3 (DE, DC, MD, PN, VA, WV) | 2 (1.6) | 12 (9.4) | 113 (89.0) | ||||

| 4 (AL, FL, GA, KY, MS, NC, SC, TN) | 4a (1.0) | 22 (5.4) | 380 (93.6) | ||||

| 5 (IL, IN, MI, MN, OH, WI) | 16 (3.0) | 41 (7.8) | 472 (89.2) | ||||

| 6 (AK, LA, NM, OK, TX) | 2 (0.9) | 9 (3.9) | 219 (95.2) | ||||

| 7 (IA, KS, MO, NE) | 11 (3.3) | 20 (6.0) | 305 (90.8) | ||||

| 8 (CO, MT, ND, SD, UT, WY) | 8 (4.6) | 14 (8.0) | 153 (87.4) | ||||

| 9 (AZ, CA, HI, NV) | 8b (10.0) | 7 (8.8) | 65 (81.3) | ||||

| 10 (AK, ID, OR, WA) | 8b (9.5) | 9 (10.7) | 67 (79.8) | ||||

| State health dept has Twitter | 3.8 | 2 | .15 | ||||

| Yes | 61 (93.8) | 135 (88.8) | 2026 (86.3) | ||||

| No | 4 (6.2) | 17 (11.2) | 322 (13.7) | ||||

| State residents ever accessing Internet, % | 69.9 ±0.7 | 68.7 ±0.5 | 68.4 ±0.2 | 1.3 | 2, 2428 | .26 | |

| State residents ever using Facebook or similar application, % | 19.7 ±1.0 | 20.4 ±0.6 | 21.4 ±0.2 | 2.5 | 2, 2526 | .08 | |

| LHD is in HHS region | |||||||

| 1 (CT, ME, MA, NH, RI, VT) | 4a (0.9) | 23a (5.3) | 407b (93.8) | 225.9 | 18 | < .01 | |

| 2 (NJ, NY) | 2 (1.2) | 17a (10.4) | 145 (88.4) | ||||

| 3 (DE, DC, MD, PN, VA, WV) | 4 (3.1) | 36 (28.3) | 87 (68.5) | ||||

| 4 (AL, FL, GA, KY, MS, NC, SC, TN) | 6 (1.5) | 74 (18.2) | 326 (80.3) | ||||

| 5 (IL, IN, MI, MN, OH, WI) | 19 (3.6) | 156b (29.5) | 354a (66.9) | ||||

| 6 (AK, LA, NM, OK, TX) | 1a (0.4) | 27a (11.7) | 202b (87.8) | ||||

| 7 (IA, KS, MO, NE) | 12 (3.6) | 130b (38.7) | 194a (57.7) | ||||

| 8 (CO, MT, ND, SD, UT, WY) | 6 (3.4) | 51b (29.1) | 118 (67.4) | ||||

| 9 (AZ, CA, HI, NV) | 7b (8.8) | 17 (21.3) | 56 (70.0) | ||||

| 10 (AK, ID, OR, WA) | 4 (4.8) | 24 (28.6) | 56 (66.7) | ||||

| State health dept has Facebook | 7.0 | 2 | .03 | ||||

| Yes | 42 (64.6) | 279 (50.3) | 940 (48.3) | ||||

| No | 23 (35.4) | 276 (49.7) | 1005 (51.7) | ||||

| State residents ever accessing Internet, % | 69.2 ±0.7 | 68.6 ±0.3 | 68.4 ±0.2 | 0.6 | 2, 2428 | .58 | |

| State residents ever using Facebook or similar application, % | 61.8 ±1.0 | 60.2c ±0.4 | 61.4d ±0.2 | 4.4 | 2, 2514 | .01 | |

Note. HHS = US Department of Health and Human Services; LHD = local health departments.

Standardized residuals were < −1.96, indicating significantly fewer LHDs than expected in this category.

Standardized residuals were > 1.96, indicating significantly more LHDs than expected in this category.

Significantly different from nonadopter mean based on Bonferroni post hoc test.

Significantly different from early adopter/majority mean based on Bonferroni post hoc test.

FIGURE 2—

Geographic distribution among local health departments nationwide of (a) Twitter and (b) Facebook: United States, 2012.

Of the innovator Twitter adopters, 93.8% were in a state where the state health department had a Twitter account. Of those innovators adopting Facebook, 64.6% were in states where the state health department had a Facebook account (Table 1).

Social Media Adoption and Statewide Internet Use

There was no significant difference in the percent of state residents accessing the Internet across the 3 adoption categories for Twitter or Facebook (Table 1). For Facebook, the percentage of state residents who reported using Facebook or a related service was significantly lower among LHDs in early adopter or majority states than in nonadopting states.

Innovators for both Twitter and Facebook were in the largest jurisdictions (Table 2) compared with early adopter or majority LHDs and nonadopters. Innovators were more likely than expected to have a top executive with a doctorate for both Twitter and Facebook, whereas Twitter early adopter or majority LHDs were also more likely than expected to have a doctorate-level top executive. In addition, innovator and early adopter or majority LHDs for Facebook and Twitter were more likely than expected to have a PIS employee, whereas nonadopters were less likely than expected to have a PIS. Spending per capita was highest in innovator health departments and lowest in nonadopting health departments for both Twitter and Facebook. The number of tweets per month in LHDs with Twitter was significantly, but weakly, correlated with jurisdiction population (r = 0.3; P < .001) and having a PIS (r = 0.2; P = .03). The number of tweets per month was not significantly correlated with spending per capita. There was no significant difference in the average number of tweets per month for innovators compared with early adopters or early majority LHDs.

TABLE 2—

Relationship between Local Health Department Characteristics and Adoption of Twitter and Facebook: United States, 2012

| Variable | Innovator, No. (%) or (Mean ±SE). | Early Adopter/Majority, No. (%) or (Mean ±SE). | Nonadopters, No. (%) or No. (Mean ±SE) | χ2 | F | Adj R2 | df | P |

| Twitter adopters | ||||||||

| LHD population (in thousands) | 63 (794.4a ±205.8) | 141 (284.8b ±39.4) | 2062 (92.8c ±4.6) | 134.1 | 0.11 | < .01 | ||

| LHD spending per capita | 59 (77.3d ±13.9) | 123 (71.8d ±13.9) | 1528 (54.8c ±1.3) | 6.6 | 0.006 | < .01 | ||

| LHD top executive education level | 51.6 | 6 | < .01 | |||||

| Associates | 0e (0.0) | 2e (1.5) | 132 (98.5) | |||||

| Bachelors | 9e (1.5) | 27e (4.5) | 563 (94.0) | |||||

| Masters | 28 (3.1) | 65 (7.2) | 805 (89.6) | |||||

| Doctorate | 24f (6.4) | 44f (11.8) | 305 (81.8) | |||||

| LHD has public information specialist | 44f (11.0) | 63f (15.7) | 294e (73.3) | 162.1 | 2 | < .01 | ||

| Facebook adopters | ||||||||

| LHD population (in thousands) | 60 (396.7a ±87.3) | 507 (166.3b ±23.4) | 1699 (102.1c ±0.7) | 22.3 | 0.02 | < .01 | ||

| LHD spending per capita | 55 (76.7d ±14.7) | 435 (61.8 ±4.3) | 1220 (54.2g ±1.5) | 4.6 | 0.004 | .01 | ||

| LHD top executive education level | 17.9 | 6 | < .01 | |||||

| Associates | 1 (0.7) | 39 (29.1) | 94 (70.1) | |||||

| Bachelors | 8e (1.3) | 135 (22.5) | 456 (76.1) | |||||

| Masters | 34 (3.8) | 211 (23.5) | 653 (72.7) | |||||

| Doctorate | 19f (5.1) | 91 (24.4) | 263 (70.5) | |||||

| LHD has public information specialist | 32f (8.0) | 148f (36.9) | 221e (55.1) | 89.8 | 2 | < .01 | ||

Note. LHD = local health department.

Significantly different from early adapter/majority and nonadopter means.

Significantly different from innovator and nonadopter means.

Significantly different from innovator and early adopter/majority means.

Significantly different from nonadopter mean only.

Standardized residuals were < −1.96, indicating significantly fewer LHDs than expected in this category.

Standardized residuals were > 1.96, indicating significantly more LHDs than expected in this category.

Significantly different from innovator mean only.

Likes and Followers of Local Health Departments

LHD Facebook and Twitter accounts had few likes and followers in general. On average, each LHD Facebook account had 127 likes (SD = 223) and each Twitter account had 413 followers (SD = 911), for an average of 3.0 Twitter followers and 3.3 Facebook likes for every 1000 residents of a jurisdiction. The number of Facebook likes was significantly (t[69] = 4.6; P < .01) and notably higher for innovators compared with early adopter or majority LHDs, with innovators having 303.0 followers on average and early adopter or majority LHDs having 105.9 followers. For Twitter, the significant difference between innovators and early adopter or majority (t[65] = 4.9; P < .01) was even more pronounced, with innovators and early adopter or majority LHDs having 1033.7 and 147.1 followers on average, respectively. Because adoption date was strongly associated with the number of followers or likes, we controlled for adoption date to discern additional significant relationships with LHD characteristics.

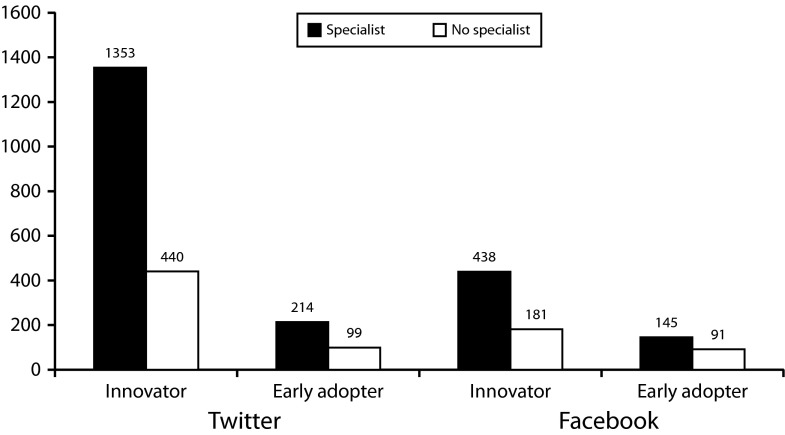

Controlling for the date of adoption, population size was significantly associated with the number of Facebook likes (r = 0.3; P < .05) and Twitter followers (r = 0.5; P < .05); the larger the population in a jurisdiction, the more people were following and liking its LHD regardless of how early the LHD adopted social media. Controlling for adoption date, the proportion of state residents accessing the Internet was not significantly associated with the number of Facebook likes or Twitter followers. Likewise, the proportion of state residents using Facebook or a related service was not significantly correlated with the number of likes, nor was state Twitter usage rate correlated with number of Twitter followers. The number of Facebook likes was significantly positively associated with spending per capita (r = 0.1; P < .05). Number of Twitter followers was also significantly associated with spending per capita (r = 0.2; P < .05), controlling for adoption date. For innovators, the average number of Facebook likes was significantly higher (t[46] = −3.2; P < .01) in jurisdictions with a specialist compared with those without a specialist. For early adopter or majority LHDs, the average number of Facebook likes was also significantly higher (t[424] = −2.7; P < .01) in jurisdictions with a specialist compared with those without a specialist. The same was true for Twitter; LHDs that employed a PIS had significantly more followers for innovators (t[57] = −3.1; P < .05) and early (t[44] = −3.1; P < .05) adopter or majority LHDs compared with LHDs without a PIS. Figure 3 demonstrates these differences.

FIGURE 3—

Number of likes and followers for early and late adopters with and without a public information specialist: United States, 2012.

Finally, controlling for jurisdiction population, the number of Twitter followers was significantly correlated with the number of tweets per month (r = 0.5; P < .001); therefore, the more active a Twitter feed, the more followers it had, regardless of LHD size.

DISCUSSION

Many LHDs nationwide have adopted at least 1 form of social media. LHD size and geographic location were associated with earlier adoption; specifically, consistent with the earlier work examining the provision of ES3,30 LHDs serving larger populations were more likely to be innovators or in the early adopter or majority group than LHDs in smaller jurisdictions. Innovators were found in the largest proportion of jurisdictions in the western states for both Twitter and Facebook, whereas fewer LHDs than expected adopted either social media platform in the northeastern states. Patterns across adoption categories indicated that, although Facebook was more widely adopted than Twitter, Twitter was adopted by larger health departments than those adopting Facebook. This was consistent with reported higher use of Twitter by the general public in suburban and urban areas.11

The overall number of likes and followers was low for both types of social media. LHDs serving larger populations and those with a PIS had significantly more likes and followers, regardless of adoption date. However, these relationships were notably stronger for Twitter than for Facebook. Thus, in addition to Twitter being more popular among larger health departments, population size had a stronger association with Twitter connections (followers) than it did with Facebook connections (likes). In LHDs with Twitter, regardless of size, tweeting more frequently was associated with having more followers. Therefore, 1 strategy for increasing connections through Twitter for any LHD would be to increase tweet frequency.

According to Diffusion of Innovations theory, the earliest adopters of a new technology, innovators, are often considered risk-takers who are not well integrated into a system. It is not clear if this is the case with social media. Although the innovators appear different from the early adopter or majority LHDs in ways consistent with Diffusion of Innovations theory (e.g., larger health departments with more resources), they also have a much greater number of followers and likes than the early adopter or majority group. For this reason, researchers and practitioners may seek out both innovators and early adopter or majority LHDs as partners in developing, disseminating, and implementing new Web 2.0 public health strategies.8,29

Health departments slow to adopt, or nonadopters, may be facing organizational barriers common to governmental public health organizations.4 These barriers include lengthy approval processes for new projects, policies that hinder social media use once it is adopted, a lack of a reliable and fast Internet connection, and firewalls that prohibit social media use by employees.35 Given our findings related to top executive education and PISs, these health departments may also lack the type of staff supportive of adoption and able to manage a social media account. Considering the lack of evidence regarding effective uses of social media for public health practice, nonadopters may also be waiting for more information.

Limitations included the cross-sectional nature of the study; social media is changing extremely quickly, and this change was not captured. Another limitation of the study was the use of the 2010 Profile data and 2010 state-level Internet usage data. Although 2010 was the most current year of data available, it predated the social media data collection by more than a year, so recent changes in LHD characteristics and Internet access might not be reflected in this study. The Profile data were also missing for nonresponding LHDs, which we found to be less likely than expected to have adopted Facebook or Twitter. This might have influenced our results; nonresponding LHDs were likely to be smaller, so we anticipated that the differences in social media adoption related to LHD size would have been even greater had data been available for the nonresponding LHDs. In addition, the strategies used in this study did not examine the characteristics of those who friended or followed LHDs on Facebook or Twitter, so we did not yet know who the LHDs were reaching and whether those receiving the information were benefiting from it or spreading it to others who might benefit.

Public use of social media is widespread and growing, as is the use of social media for seeking health information. LHDs have a unique opportunity to meet the local public need for health information by taking advantage of existing social media communication pathways and knowledge of local public health problems and opportunities to educate and inform their constituents. However, reaching constituents with health information through social media is only useful if it is effective in improving public health. In studies outside LHDs, social media has been effective in promoting condom use,36 educating low-income parents about child safety and health,37,38 and increasing the likelihood that new moms will stay smoke-free.39 Similar studies should be undertaken to determine the most effective ways for LHDs to use social media to educate and inform local constituents.

Social media connections also have the potential to provide pathways for LHDs and other public health organizations to share lessons learned and best practices. Understanding these pathways may be useful in facilitating more efficient dissemination of evidence-based practices and other information across the public health system. Although the potential of social media to influence and improve public health seems great, additional evidence is needed on how LHDs and other health organizations can most effectively use this new tool.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Carolyn Leep at the National Association for County and City Health Officials for her assistance with data-related questions.

Human Participant Protection

Human participant protection was not needed for this study because only secondary and archival data were used.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Public Health Performance Standards Program (NPHPSP). 10 Essential public health services. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nphpsp/essentialServices.html. Accessed July 9, 2012.

- 2. Public Health Accreditation Board. Standards and measures. 2011. Available at: http://www.phaboard.org/accreditation-process/public-health-department-standards-and-measures. Accessed June 8, 2012.

- 3.Mays GP, McHugh MC, Shim K et al. Getting what you pay for: public health spending and the performance of essential public health services. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10(5):435–443. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200409000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schein R, Wilson K, Keelan J. Literature review on effectiveness of the use of social media: a report for Peel public health. Peel Public Health. 2010. Available at: http://www.peelregion.ca/health/resources/pdf/socialmedia.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2012.

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The health communicator’s social media toolkit. 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/socialmedia/Tools/guidelines/pdf/SocialMediaToolkit_BM.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2012.

- 6.Madden M, Zickuhr K. 65% of online adults use social networking sites. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Available at: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Social-Networking-Sites.aspx. Published August 26, 2011. Accessed June 8, 2012.

- 7. eBiz MBA. Top 15 most population social networking sites. 2012. Available at: http://www.ebizmba.com/articles/social-networking-websites. Accessed September 30, 2012.

- 8.Currie D. More health departments nationwide embracing social media: use of tools rises. Nations Health. 2012;42(4):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tieman J. The Facebook frontier: compelling social media can transform health dialogue. Health Prog. 2012;93(2):82–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou WYS, Hunt YM, Beckjord EB, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Social media use in the United States: implications for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(4):e48. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Twitter use 2012. 2012. Available at: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Twitter-Use-2012/Findings.aspx. Accessed September 30, 2012.

- 12.Vance K, Howe W, Dellavalle RP. Social internet sites as a source of public health information. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27(2):133–136. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Web 2.0. 2011. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/topics/Web-20.aspx. Accessed June 8, 2012.

- 14.Couper MP, Singer E, Levin CA, Fowler FJ, Fagerlin A, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Use of the internet and ratings of information sources for medical decisions: results from the DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(5 suppl):106S–114S. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10377661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox S. The social life of health information, 2011. 2011. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Available at: http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Social-Life-of-Health-Info.aspx. Accessed July 13, 2012.

- 16.Chu LF, Young C, Zamora A, Kurup V, Macario A. Anesthesia 2.0: Internet-based information resources and Web 2.0 applications in anesthesia education. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2010;23(2):218–227. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328337339c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapp JM, LeMaster JW, Lyon NB, Zhang B, Hosokawa MC. Updating public health teaching methods in the era of social media. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(6):775–777. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau AS. Hospital-based nurses’ perceptions of the adoption of Web 2.0 tools for knowledge sharing, learning, social interaction and the production of collective intelligence. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e92. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawn C. Take two aspirin and tweet me in the morning: how Twitter, Facebook, and other social media are reshaping health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(2):361–368. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones B. Mixed uptake of social media among public health specialists. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(11):784–785. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.031111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sublet V, Spring C, Howard J National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. Does social media improve communication? Evaluating the NIOSH science blog. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54(5):384–394. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt CW. Trending now: using social media to predict and track disease outbreaks. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(1):A30–A33. doi: 10.1289/ehp.120-a30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Usher WT. Australian health professionals’ social media (Web 2.0) adoption trends: early 21st century health care delivery and practice promotion. Aust J Prim Health. 2012;18(1):31–41. doi: 10.1071/PY10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris JK, Snider D, Mueller NL. Social media adoption in health departments nationwide: the state of the states. Front Public Health Serv Syst Res. 2013;2(1):5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thackeray R, Neiger BL, Smith AK, Van Wagenen SB. Adoption and use of social media among public health departments. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):242–247. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. National Association of County and City Health Officials. 2010 National profile of local health departments. 2011. Available at: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/profile/resources/2010report/upload/2010_Profile_main_report-web.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2012.

- 27. National Association of County and City Health Officials. Informatics needs assessment of LHDs. 2010. Available at: http://www.naccho.org/topics/infrastructure/informatics/needs-assessment.cfm. Accessed June 8, 2012.

- 28. National Association of County and City Health Officials. Directory of local health departments (LHD index). 2012. Available at: http://www.naccho.org/about/LHD. Accessed December 10, 2011.

- 29.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mays GP, McHugh MC, Shim K et al. Institutional and economic determinants of public health system performance. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):523–531. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhandari MW, Scutchfield FD, Charnigo R, Riddell MC, Mays GP. New data, same story? Revisiting studies on the relationship of local public health systems characteristics to public health performance. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(2):110–117. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181c6b525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pew Internet & American Life Project. September 2010-health tracking. 2010. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Shared-Content/Data-Sets/2010/September-2010–Health.aspx. Accessed September 30, 2012.

- 33.Harris JK. The network of Web 2.0 connections among state health departments: new pathways for dissemination. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013 doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318268ae36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. US Department of Health & Human Services. HHS region map. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/about/regionmap.html. Accessed September 30, 2012.

- 35.Hudson M. Web 2.0 & social media: Lessons learned. Presented at: 62nd Annual Institute of Public Administration of Canada Conference, June 17, 2010; Ottawa, Canada.

- 36.Purdy CH. Using the internet and social media to promote condom use in Turkey. Reprod Health Matters. 2011;19(37):157–165. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(11)37549-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gualtieri L. The potential for social media to educate farm families about health and safety for children. J Agromedicine. 2012;17(2):232–239. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2012.658268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stroever SJ, Mackert MS, McAlister AL, Hoelscher DM. Using social media to communicate child health information to low-income parents. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(6):A148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowe JB, Barnes M, Teo C, Sutherns S. Investigating the use of social media to help women from going back to smoking post-partum. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2012;36(1):30–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]