Abstract

Objectives. We examined differences in the use of mental health services, conditional on the presence of psychiatric disorders, across groups of Mexico’s population with different US migration exposure and in successive generations of Mexican Americans in the United States.

Methods. We merged surveys conducted in Mexico (Mexican National Comorbidity Survey, 2001–2002) and the United States (Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys, 2001–2003). We compared psychiatric disorders and mental health service use, assessed in both countries with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, across migration groups.

Results. The 12-month prevalence of any disorder was more than twice as high among third- and higher generation Mexican Americans (21%) than among Mexicans with no migrant in their family (8%). Among people with a disorder, the odds of receiving any mental health service were higher in the latter group relative to the former (odds ratio = 3.35; 95% confidence interval = 1.82, 6.17) but the age- and gender-adjusted prevalence of untreated disorder was also higher.

Conclusions. Advancing understanding of the specific enabling and dispositional factors that result in increases in mental health care may contribute to reducing service use disparities across ethnic groups in the United States.

Epidemiological studies have found that migration from Mexico to the United States is associated with a dramatic increase in psychiatric morbidity. Risk for a broad range of psychiatric disorders, which is relatively low in the Mexican general population, is higher among Mexican-born immigrants in the United States and higher still among US-born Mexican Americans.1–5 Risk among US-born Mexican Americans is similar to that of the non-Hispanic White population.6 Recent research suggests that the association between migration and mental health extends into Mexico, where return migrants and family members of migrants are at higher risk for substance use disorders than those with no migrant in their family.3,7

Little is known about the influence of cultural and social changes associated with migration on the use of mental health services. As the mental health system is much more extensive8 and use of mental health service is much more common9 in the United States than in Mexico, we expect that Mexican Americans would use mental health services more frequently than their counterparts in Mexico. However, it is not known whether the increase in service use keeps pace with the increase in prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Moreover, in the United States, Hispanics in general and Mexican Americans in particular are less likely to receive mental health services than are non-Hispanic Whites,10–12 and immigrants are less likely to use mental health services than the US born, particularly if they are undocumented.13

We made use of a unique data set formed by merging surveys conducted in Mexico and the United States that used the same survey instrument. We used these data to examine differences in past-year mental health service use, conditional on the past-year prevalence of psychiatric disorder, associated with migration on both sides of the Mexico–US border.

METHODS

We combined and analyzed data on the Mexican population from the Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS)14 together with data on the Mexican-origin population in the United States from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES).15 The MNCS, conducted as part of the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative,16 is based on a stratified, multistage area probability sample of household residents in Mexico aged 18 to 65 years who lived in communities with a population of at least 2500 people. A total of 5782 respondents were interviewed between September 2001 and May 2002. The response rate was 76.6%.

Two component surveys of the CPES include respondents of Mexican descent: the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCSR)17 and the National Latino and Asian American Survey (NLAAS).10,18 The NCSR was based on a stratified multistage area probability sample of the English-speaking household population of the continental United States. The NLAAS was based on the same sampling frame as the NCSR, with special supplements to increase representation of the survey’s target ethnic groups. Spanish-language interviews in the NLAAS used the same translation of the diagnostic interview modules as were used in the MNCS. The NCSR was conducted from 2001 through 2003 and had a 70.9% response rate; the NLAAS was conducted from 2002 through 2003 and had a 75.5% response rate for the Latino sample. The combined sample of Mexican Americans comprised 1442 respondents, 1214 of whom were selected for the long form of the survey, which included questions regarding nativity and age at immigration. Six respondents were dropped because of missing data. The sample was weighted with integrated weights developed by CPES biostatisticians19 based on the common sampling frame to properly adjust the CPES sample to the US national population within racial/ethnic groups.

Measures

We defined 5 mutually exclusive groups representing a range of exposure to the United States across this transnational population:

no migrant in family (MNCS);

members of migrant households (MNCS);

first-generation migrants: Mexico-born immigrants in the United States who arrived in the United States at age 13 years or older (US CPES);

1.5- or second-generation migrants: Mexico-born immigrants who arrived in the United States before age 13 years and US-born children of immigrants, respectively (US CPES); and

third- or higher generation: US-born Mexican Americans with at least 1 US-born parent (US CPES).

Psychiatric disorders were assessed according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria by using the World Mental Health version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview.20,21 Eleven disorders were assessed in all 3 surveys, including 2 mood disorders (major depressive episode and dysthymia), 5 anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia without panic disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder), and 4 substance use disorders (abuse and dependence of alcohol and drugs). A composite indicator of severity of mental disorder in the past 12 months was defined as described elsewhere.22 Blinded clinical reappraisal interviews found generally good concordance between DSM-IV diagnoses based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview23 and those based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.24

Respondents were asked about receipt of services for emotional, alcohol, or drug problems; the type of provider from which services were received; and the type and frequency of services received. Using methods described elsewhere,9,10,14,25,26 we divided mental health care service providers into the following 5 types:

psychiatrists;

other mental health specialists, consisting of psychologists, counselors, psychotherapists, mental health nurses, and social workers in a mental health specialty setting;

general medical practitioners, consisting of family physicians, general practitioners, and other medical doctors, such as cardiologists, or gynecologists (for women) and urologists (for men), nurses, occupational therapists, or other health care professionals;

human services, including outpatient treatment with a religious or spiritual advisor or a social worker or counselor in any setting other than a specialty mental health setting, or a religious or spiritual advisor, such as a minister, priest, or rabbi; and

complementary–alternative medicine including Internet use, such as self-help groups; any other healer, such as an herbalist, a chiropractor, or a spiritualist; and other alternative therapies.

We classified provider types by service sector into the health sector, the specialty mental health sector, and the non–health care sector.

We defined minimally adequate treatment as receiving (1) 4 or more outpatient psychotherapy visits to any provider,27,28 (2) 2 or more outpatient pharmacotherapy visits to any provider and treatment with any medication for any length of time,29 or (3) reporting still being “in treatment” at the time of the interview. Although this definition is broader than one used in other reports,30 it brings conservative estimates of minimally adequate treatment across sectors. In sensitivity analyses, we also used a more stringent definition of minimally adequate treatment: (1) 8 or more visits to any service sector for psychotherapy or (2) 4 or more visits to any service sector for pharmacotherapy and 30 or more days taking any medication.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated standard errors and significance tests by the Taylor series method with SUDAAN version 10.0.1 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) to adjust for the weighting and clustering of the data. We compared the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and use of various types of mental health services across migration groups with a design-adjusted χ2 test. We estimated age- and gender-adjusted prevalence of disorders, treatment, and untreated disorders by using SUDAAN’s PROC DESCRIPT. We used logistic regression models to estimate covariate-adjusted relative odds of service use and receipt of minimally adequate treatment across the migration groups. We estimated separate models in the entire sample and in the subsample meeting criteria for a psychiatric disorder.

We adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for design effects. We evaluated all tests for statistical significance at the .05 level of significance.

RESULTS

All demographic variables were differentially distributed across the 5 groups, with at least 1 group statistically different from the others, as all the P values for the χ2 independence test were less than .05 (Table 1). Apparently, first-generation migrants were more likely to be male, older, and married. The Mexican-origin groups living in the United States had higher levels of education than those living in Mexico.

TABLE 1—

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Mexican Sample (n = 6990): Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (2001–2002) and Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (2001–2003)

| Characteristic | No Migrant in Family (n = 2878), % | Members of Migrant Householdsa (n = 2904), % | First-Generation Migrantsb (n = 412), % | 1.5- or Second-Generation Migrantsc (n = 308), % | Third- or Higher Generation Migrantsd (n = 488), % | χ2 (df) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 45.67 | 49.69 | 56.95 | 50.19 | 52.15 | 13.61 (4)* |

| Female | 54.33 | 50.31 | 43.05 | 49.81 | 47.85 | |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18–25 | 28.86 | 26.33 | 15.34 | 38.62 | 29.99 | 67.03 (12)*** |

| 26–35 | 27.41 | 29.56 | 40.05 | 26.40 | 19.24 | |

| 36–45 | 20.90 | 22.33 | 25.33 | 11.36 | 22.59 | |

| ≥ 46 | 22.82 | 21.77 | 19.29 | 23.62 | 28.18 | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married or cohabiting | 65.24 | 69.65 | 78.42 | 54.91 | 59.57 | 44.70 (8)*** |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 7.82 | 6.70 | 8.73 | 13.47 | 14.27 | |

| Never married | 26.94 | 23.65 | 12.85 | 31.62 | 26.16 | |

| Education, y | ||||||

| 0–5 | 19.74 | 14.91 | 17.59 | 8.28 | 4.43 | 204.35 (12)*** |

| 6–8 | 21.92 | 21.32 | 32.36 | 8.58 | 4.09 | |

| 9–11 | 30.24 | 27.58 | 20.63 | 23.75 | 23.69 | |

| ≥ 12 | 28.11 | 36.19 | 29.43 | 59.38 | 67.78 |

Note. Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS): Mexican sample of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCSR) and the National Latino and Asian American Survey (NLAAS). Table shows unweighted frequencies, weighted percentages. Percentages may not total 100% because of rounding.

Mexican with a migrant in family or who migrated and returned to Mexico (from the MNCS).

Mexico-born, migrated at age 13 years or older (from the NLAAS and NCSR).

Mexico-born, migrated at age 12 years or younger, or US-born Mexican descent, no US-born parents (NLAAS and NCSR).

US-born, Mexican descent, at least 1 US-born parent (NLAAS and NCSR).

*P < .05; ***P < .001; P values determined by the Wald test.

Migration group was significantly related to the 12-month prevalence of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders, with higher prevalence found in the groups living in the United States, particularly those who spent at least part of their childhood in the United States, the 1.5-, second-, third-, and higher generation Mexican Americans (Table 2). Across the 5 groups the 12-month prevalence of any disorder more than doubled from 8.15% in the Mexicans with no migrant in their family to 21.39% in the third-generation and higher Mexican Americans. Among people with a disorder, the distribution across levels of severity (severe, moderate, mild) did not differ across migrant groups (χ2(8) = 9.43; P = .31).

TABLE 2—

Crude Prevalence of 12-Month Mental Disorders Among Mexican Categories: Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (2001–2002) and Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (2001–2003)

| Disordera | No Migrant in Family (n = 2878), % (SE) | Members of Migrant Households (n = 2904), % (SE) | First-Generation Migrants (n = 412), % (SE) | 1.5- or Second-Generation Migrants (n = 308), % (SE) | Third- or Higher Generation Migrants (n = 488), % (SE) | χ2 (df)b |

| Mental disorder | ||||||

| Major depressive episode | 4.05 (0.43) | 3.93 (0.36) | 5.88 (0.95) | 7.55 (1.79) | 10.28 (1.46) | 61.12 (4)*** |

| Dysthymia | 1.10 (0.21) | 0.6 (0.16) | 1.60 (0.74) | 1.09 (0.61) | 1.96 (0.66) | 9.51 (4)* |

| Any mood disorder | 4.14 (0.43) | 4.00 (0.37) | 5.88 (0.95) | 7.55 (1.79) | 10.28 (1.46) | 59.14 (4)*** |

| Agoraphobia without panic disorder | 1.08 (0.21) | 0.70 (0.12) | 2.36 (0.85) | 0.70 (0.36) | 2.95 (1.18) | 24.30 (4)*** |

| Social phobia | 2.20 (0.28) | 1.87 (0.28) | 2.90 (1.04) | 4.41 (1.09) | 6.61 (1.06) | 42.92 (4)*** |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 0.57 (0.16) | 0.54 (0.13) | 1.43 (0.43) | 1.75 (0.53) | 2.37 (0.59) | 27.85 (4)*** |

| Panic disorder | 0.62 (0.13) | 0.74 (0.22) | 1.19 (0.32) | 2.00 (0.93) | 3.75 (0.72) | 47.82 (4)*** |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 0.39 (0.13) | 0.54 (0.20) | 1.68 (0.80) | 1.53 (0.64) | 4.04 (1.07) | 50.08 (4)*** |

| Any anxiety disorder | 4.04 (0.40) | 3.56 (0.38) | 6.89 (1.68) | 8.09 (1.71) | 13.25 (1.71) | 85.27 (4)*** |

| Substance use disorder | ||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 1.24 (0.31) | 2.87 (0.52) | 0.49 (0.26) | 3.75 (1.74) | 3.92 (0.87) | 17.30 (4)** |

| Alcohol dependence | 0.87 (0.29) | 1.26 (0.32) | 0.43 (0.27) | 2.07 (1.14) | 2.06 (0.67) | 4.97 (4) |

| Drug abuse | 0.13 (0.06) | 0.44 (0.16) | 0.42 (0.29) | 0.96 (0.56) | 1.68 (0.57) | 18.47 (4)** |

| Drug dependence | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.19 (0.09) | 0.35 (0.35) | … | 0.60 (0.27) | 291.14 (4)*** |

| Any substance use disorder | 1.38 (0.31) | 3.33 (0.53) | 1.25 (0.62) | 4.32 (1.82) | 5.64 (1.01) | 19.94 (4)*** |

| Any disorder | 8.15 (0.68) | 9.06 (0.81) | 10.98 (1.43) | 16.54 (2.32) | 21.39 (2.00) | 88.82 (4)*** |

| Any disorder severityc | ||||||

| Severe | 33.56 (4.30) | 43.56 (4.21) | 38.74 (5.83) | 40.10 (9.29) | 42.77 (5.37) | 9.43 (8) |

| Moderate | 45.09 (3.70) | 36.85 (4.11) | 40.89 (8.18) | 37.55 (7.53) | 44.75 (5.00) | … |

| Mild | 21.35 (3.21) | 19.58 (2.51) | 20.37 (6.82) | 22.34 (6.26) | 12.49 (2.32) | … |

Note. Table shows unweighted frequencies, weighted percentages. Ellipses indicate that there were no positives cases in the category.

Only mental disorders common to the 3 surveys: Mexican National Comorbidity Survey, National Comorbidity Survey Replication, and National Latino and Asian American Survey.

We computed all χ2 with 4 df tests by logistic regression after adjustment by age and gender.

Column percentages.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; P values determined by the Wald test.

Table 3 shows past-year mental health service use by care sector and provider type among the whole sample and separately for people with and without a mental disorder in the past year. In the whole sample, the prevalence of use of any service was significantly associated with migration, increasing between migration groups from a low of 4.54% among Mexicans with no migrant in their family to a high of 16.56% among third- and higher generation Mexican Americans (χ2(4) = 47.98; P < .001). This pattern was consistent across sectors and across provider types with the exception of services provided by psychiatrists, where difference associated with migrant group did not reach statistical significance (χ2(4) = 5.54; P = .24).

TABLE 3—

Prevalence of 12-Month Service Use by Migrant Status and Type of Provider: Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (2001–2002) and Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (2001–2003)

| No Migrant in Family | Members of Migrant Households | First-Generation Migrants | 1.5- or Second-Generation Migrants | Third- or Higher Generation Migrants | ||||||||||||

| Freq. | No. | % (SE) | Freq. | No. | % (SE) | Freq. | No. | % (SE) | Freq. | No. | % (SE) | Freq. | No. | % (SE) | χ2(4 df) | |

| Whole population (n = 6990) | 2878 | 2904 | 412 | 308 | 488 | |||||||||||

| Any service | 153 | 4.54 (0.49) | 174 | 5.78 (0.57) | 22 | 4.97 (1.17) | 45 | 11.44 (1.76) | 108 | 16.56 (1.53) | 47.98*** | |||||

| Any health care | 126 | 3.56 (0.44) | 153 | 5.04 (0.52) | 19 | 4.39 (1.17) | 32 | 7.53 (1.35) | 89 | 13.37 (1.56) | 33.51*** | |||||

| Any mental health care | 77 | 2.21 (0.30) | 85 | 2.94 (0.35) | 10 | 2.71 (0.74) | 21 | 5.24 (1.25) | 46 | 7.27 (1.32) | 14.38** | |||||

| Psychiatrist | 26 | 0.84 (0.19) | 18 | 0.84 (0.24) | 5 | 1.39 (0.75) | 10 | 2.39 (0.99) | 19 | 2.71 (0.73) | 5.54 | |||||

| Other mental health care | 56 | 1.52 (0.24) | 72 | 2.20 (0.27) | 8 | 1.92 (0.45) | 17 | 4.14 (0.91) | 40 | 6.63 (1.34) | 15.67** | |||||

| General medical | 55 | 1.52 (0.27) | 76 | 2.40 (0.34) | 12 | 2.66 (0.96) | 17 | 3.67 (0.70) | 59 | 8.54 (1.02) | 40.59*** | |||||

| Non–health care | 36 | 1.30 (0.21) | 27 | 0.99 (0.24) | 5 | 0.92 (0.54) | 21 | 5.92 (1.66) | 42 | 6.86 (1.11) | 30.24*** | |||||

| Human service | 6 | 0.23 (0.11) | 10 | 0.27 (0.10) | 4 | 0.73 (0.44) | 9 | 2.40 (0.97) | 32 | 5.33 (0.99) | 32.39*** | |||||

| Complementary–alternative medicine | 32 | 1.19 (0.21) | 21 | 0.80 (0.24) | 2 | 0.34 (0.22) | 12 | 3.52 (1.41) | 14 | 2.22 (0.80) | 13.40** | |||||

| Among any 12-mo disorder diagnosis (n = 788)a | 267 | 265 | 50 | 65 | 141 | |||||||||||

| Any service | 59 | 18.56 (2.65) | 63 | 24.97 (3.19) | 11 | 24.04 (7.37) | 23 | 34.84 (6.27) | 64 | 42.27 (3.98) | 23.55*** | |||||

| Any health care | 53 | 16.40 (2.47) | 53 | 21.78 (2.87) | 10 | 22.75 (7.46) | 18 | 25.54 (5.74) | 57 | 37.38 (3.85) | 17.14** | |||||

| Any mental health care | 32 | 10.86 (1.93) | 32 | 14.90 (2.66) | 7 | 17.20 (5.94) | 13 | 18.93 (5.20) | 25 | 15.83 (2.99) | 3.20 | |||||

| Psychiatrist | 15 | 6.02 (1.72) | 10 | 6.13 (2.05) | 5 | 12.70 (5.96) | 7 | 9.73 (5.36) | 14 | 9.23 (2.62) | 1.74 (0.784) | |||||

| Other mental health care | 21 | 6.54 (1.48) | 23 | 8.99 (2.15) | 5 | 10.05 (4.65) | 12 | 16.95 (4.01) | 21 | 14.20 (2.94) | 11.47* | |||||

| General medical | 24 | 6.72 (1.69) | 27 | 9.17 (1.92) | 5 | 12.19 (6.71) | 9 | 12.60 (3.46) | 45 | 30.93 (4.16) | 23.92*** | |||||

| Non–health care | 9 | 3.56 (1.36) | 12 | 4.12 (1.43) | 3 | 4.36 (2.45) | 12 | 19.19 (5.98) | 21 | 14.86 (3.25) | 11.34* | |||||

| Human service | 2 | 0.82 (0.60) | 5 | 1.31 (0.80) | 2 | 2.69 (1.93) | 5 | 8.84 (4.13) | 17 | 11.87 (2.50) | 23.98*** | |||||

| Complementary–alternative medicine | 7 | 2.73 (1.18) | 9 | 3.11 (1.21) | 2 | 3.07 (2.09) | 7 | 10.35 (5.62) | 6 | 4.78 (2.50) | 1.66 | |||||

| Among non–12-mo disorder diagnosis (n = 6202) | 2611 | 2639 | 362 | 243 | 347 | |||||||||||

| Any service | 94 | 3.29 (0.42) | 111 | 3.87 (0.43) | 11 | 2.61 (0.83) | 22 | 6.80 (1.47) | 44 | 9.56 (1.69) | 21.17*** | |||||

| Any health care | 73 | 2.43 (0.37) | 100 | 3.38 (0.38) | 9 | 2.12 (0.84) | 14 | 3.96 (1.19) | 32 | 6.83 (1.48) | 12.43* | |||||

| Any mental health care | 45 | 1.45 (0.27) | 53 | 1.75 (0.22) | 3 | 0.92 (0.68) | 8 | 2.53 (0.89) | 21 | 4.93 (1.33) | 7.37 | |||||

| Psychiatrist | 11 | 0.38 (0.14) | 8 | 0.31 (0.13) | … | … | 3 | 0.93 (0.54) | 5 | 0.93 (0.44) | 16.42** | |||||

| Other mental health care | 35 | 1.08 (0.22) | 49 | 1.52 (0.18) | 3 | 0.92 (0.68) | 5 | 1.60 (0.69) | 19 | 4.57 (1.33) | 8.20 | |||||

| General medical | 31 | 1.06 (0.22) | 49 | 1.72 (0.32) | 7 | 1.48 (0.58) | 8 | 1.90 (0.79) | 14 | 2.44 (0.50) | 7.26 | |||||

| Non–health care | 27 | 1.10 (0.20) | 15 | 0.68 (0.21) | 2 | 0.49 (0.34) | 9 | 3.29 (1.22) | 21 | 4.68 (1.10) | 30.70*** | |||||

| Human service | 4 | 0.18 (0.11) | 5 | 0.16 (0.07) | 2 | 0.49 (0.34) | 4 | 1.13 (0.63) | 15 | 3.56 (1.01) | 33.53*** | |||||

| Complementary–alternative medicine | 25 | 1.06 (0.21) | 12 | 0.57 (0.21) | … | … | 5 | 2.16 (1.03) | 8 | 1.52 (0.62) | 29.50*** | |||||

Note. Table shows unweighted frequencies, weighted percentages. Respondents may report more than 1 provider. Ellipses indicate that there were no positives cases in the category. Mental health care service providers were divided into (1) psychiatrists; (2) other mental health specialists, consisting of psychologists, counselors, psychotherapists, mental health nurses, and social workers in a mental health specialty setting; (3) general medical practitioners, consisting of family physicians, general practitioners, and other medical doctors, such as cardiologists, or gynecologists (for women) and urologists (for men); nurses; occupational therapists; or other health care professionals; (4) human services, including outpatient treatment with a religious or spiritual advisor or a social worker or counselor in any setting other than a specialty mental health setting, or a religious or spiritual advisor, such as a minister, priest, or rabbi; and (5) complementary–alternative medicine including Internet use, such as self-help groups; any other healer, such as an herbalist, a chiropractor, or a spiritualist; and other alternative therapies. Both psychiatrists and other mental health specialty providers were grouped under “any mental health care providers”; psychiatrists, other mental health specialists, and general medical care providers under “any health care services”; human services and complementary–alternative medicine professionals under “any non–health care service.” The “any service” category was defined as at least 1 visit to any of the providers.

Only mental disorders common to the 3 surveys: Mexican National Comorbidity Survey, National Comorbidity Survey Replication, and National Latino and Asian American Survey; any disorder: any Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition20 substance, mood, or anxiety disorder.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; P values determined by the Wald test.

Use of services was much more common among people with versus without a past-year mental disorder, but the association between service use and migrant group was similar in both groups. Use of any service increased from 18.56% to 42.27% across migrant groups among those with a past-year disorder, and from 3.29% to 9.56% among those without a past-year disorder. Increases in use reached statistical significance in both the health care and the non–health care sectors. Within the health care sector and among those with a lifetime disorder, the largest increases in use were found for general medical providers, and within the non–health care sector the largest increases in use were found for human service providers.

Among service users, adequacy of care was not associated with migration group, with either the light (χ2(4) = 6.49; P = .17) or the strict definition (χ2(4) = 7.70; P = .1) of adequate care (data available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Associations between service use and migration group were sustained after we adjusted for gender, age, marital status, education, and severity of 12-month mental disorder (Table 4). Compared with Mexicans in households without a migrant, the odds of service use in the whole sample and in the subsample with a past-year mental disorder were about 2 times higher in the 1.5- or second-generation Mexican Americans and about 3 times higher in the third- or higher generation Mexican Americans.

TABLE 4—

Multivariate Logistic Regression Models of Any Treatment and Adequacy of Treatment: Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (2001–2002) and Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (2001–2003)

| Adequate Treatment Among 12-Month Any Service Users |

|||

| Variable | Any Treatmenta OR (95% CI) | Light Definition,b OR (95% CI) | Stringent Definition,c OR (95% CI) |

| Total sample (n = 6990) | |||

| Migrant status | |||

| No migrant in family (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Members of migrant households | 1.25 (0.91, 1.72) | 0.55 (0.32, 0.95) | 0.53 (0.27, 1.03) |

| First-generation migrants | 1.08 (0.64, 1.81) | 0.86 (0.27, 2.74) | 0.44 (0.14, 1.41) |

| 1.5- or second-generation migrants | 1.98 (1.27, 3.09) | 2.15 (0.91, 5.12) | 1.44 (0.64, 3.20) |

| Third- or higher generation migrants | 2.99 (2.03, 4.41) | 1.10 (0.62, 1.96) | 0.76 (0.39, 1.48) |

| Gender | |||

| Male (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 1.57 (1.20, 2.04) | 1.07 (0.60, 1.91) | 0.76 (0.46, 1.24) |

| Age, y | |||

| 18–25 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 26–35 | 1.42 (0.96, 2.09) | 0.64 (0.35, 1.20) | 1.61 (0.60, 4.32) |

| 36–45 | 1.50 (1.02, 2.21) | 1.48 (0.68, 3.22) | 2.78 (1.09, 7.11) |

| ≥ 46 | 1.60 (1.03, 2.50) | 2.03 (0.97, 4.21) | 3.04 (1.08, 8.56) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married or cohabiting | 0.93 (0.69, 1.25) | 0.47 (0.25, 0.90) | 0.64 (0.31, 1.35) |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 1.27 (0.79, 2.06) | 0.38 (0.14, 1.00) | 0.84 (0.32, 2.23) |

| Never married (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Education, y | |||

| 0–5 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 6–8 | 0.59 (0.37, 0.96) | 1.83 (0.89, 3.74) | 1.40 (0.61, 3.19) |

| 9–11 | 0.67 (0.42, 1.08) | 0.91 (0.45, 1.84) | 1.67 (0.74, 3.78) |

| ≥ 12 | 0.93 (0.63, 1.39) | 1.19 (0.62, 2.29) | 1.26 (0.54, 2.98) |

| Subsample with any DSM-IV disorder (n = 788)d | |||

| Migrant status | |||

| No migrant in family (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Members of migrant households | 1.65 (1.00, 2.72) | 0.39 (0.17, 0.90) | 0.40 (0.16, 1.01) |

| First-generation migrants | 1.53 (0.62, 3.72) | 1.47 (0.23, 9.33) | 0.53 (0.10, 2.80) |

| 1.5- or second-generation migrants | 2.36 (1.09, 5.11) | 6.57 (1.77, 24.31) | 2.61 (0.97, 7.04) |

| Third- or higher generation migrants | 3.35 (1.82, 6.17) | 1.92 (0.83, 4.48) | 1.01 (0.40, 2.56) |

| Gender | |||

| Male (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 1.20 (0.83, 1.73) | 1.38 (0.63, 3.03) | 1.04 (0.53, 2.04) |

| Age, y | |||

| 18–25 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 26–35 | 0.96 (0.55, 1.67) | 1.37 (0.60, 3.12) | 4.06 (0.97, 16.91) |

| 36–45 | 1.60 (0.87, 2.96) | 3.01 (1.03, 8.76) | 3.19 (0.66, 15.50) |

| ≥ 46 | 1.41 (0.76, 2.63) | 2.26 (0.73, 6.98) | 4.08 (0.70, 23.66) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married or cohabiting | 1.02 (0.58, 1.77) | 0.38 (0.14, 1.03) | 0.82 (0.23, 2.91) |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 1.53 (0.78, 3.00) | 0.31 (0.08, 1.18) | 0.90 (0.18, 4.43) |

| Never married (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Education, y | |||

| 0–5 (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 6–8 | 0.52 (0.26, 1.02) | 1.52 (0.55, 4.20) | 1.07 (0.32, 3.61) |

| 9–11 | 0.57 (0.28, 1.18) | 1.06 (0.39, 2.90) | 1.57 (0.53, 4.68) |

| ≥ 12 | 0.87 (0.42, 1.80) | 0.87 (0.30, 2.51) | 1.07 (0.35, 3.32) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition20; OR = odds ratio.

Models adjusted by severity of mental disorder.

The light definition of minimally adequate treatment was (1) ≥ 4 outpatient psychotherapy visits to any provider, (2) ≥ 2 outpatient pharmacotherapy visits to any provider and treatment with any medication for any length of time, or (3) reporting still being “in treatment” at the time of the interview.

The stringent definition of minimally adequate treatment was (1) ≥ 8 visits to any service sector for psychotherapy or (2) ≥ 4 visits to any service sector for pharmacotherapy and ≥ 30 days taking any medication.

Only mental disorders common to the 3 surveys: Mexican National Comorbidity Survey, National Comorbidity Survey Replication, and National Latino and Asian American Survey; any disorder: any DSM-IV substance, mood, or anxiety disorder.

Among those who received services, about half of them received adequate treatment according to the light definition, and only 1 of every 3 according to the strict definition (data not shown in table). After we controlled for demographic variables, the likelihood of receiving adequate care, according to the light or strict definition, did not consistently improve across immigration groups, either in the whole sample or in the subsample with a past-year mental disorder. First, compared with Mexicans in households without a migrant, the odds of receiving adequate care were lower among Mexicans in households with a migrant. Second, none of the other odds ratios among those with a past-year disorder were significantly larger than one for either the first- or the third- or higher generation Mexican Americans, except for the 1.5- or second-generation Mexican Americans who were significantly more likely to receive adequate care (OR = 6.57; 95% CI = 1.77, 24.31).

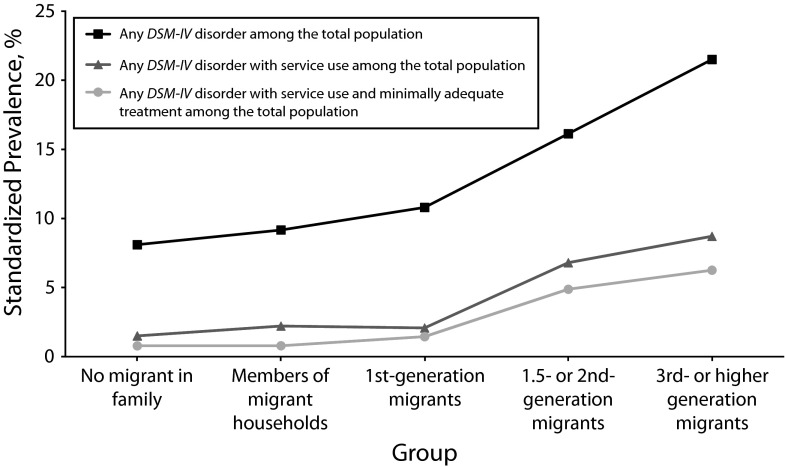

Figure 1 summarizes change in mental health status and mental health service use associated with migration. The top line shows the age- and gender-standardized prevalence of past-year mental disorder across the 5 migration groups. The lower 2 lines show the prevalence of having a past-year disorder and receiving any or receiving minimally adequate care across the 5 migration groups. The figure shows that despite the increase in the use of services and the receipt of minimally adequate care across migration groups, the absolute difference in proportions of people with a past-year disorder who did not receive care (i.e., the gap between the top line and the 2 lower lines) kept increasing across migration groups.

FIGURE 1—

Age- and gender-standardized prevalence of mental disorders, treatment, and adequacy of treatment among Mexican and Mexican-origin groups: Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (2001–2002) and Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (2001–2003).

Note. DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.20

DISCUSSION

The dramatic cultural, social, and institutional changes that occur across generations accompanying migration from Mexico to the United States include dramatic changes in need for and use of mental health services. This study is the first to our knowledge to trace these changes across the entire transnational Mexican-origin population on both sides of the Mexico–US border. The unique transnational data set allowed us to test hypothesized migration-related differences in need for mental health services, as indicated by the presence of a psychiatric disorder, and parallel differences in use of services. By combining information on need for and use of services, we were able to test migration-related differences in unmet need, defined as meeting criteria for a psychiatric disorder without receiving mental health services.

Four findings deserve attention. First, consistent with previous studies, there was a dramatic increase in the need for mental health services across migration groups as indicated by the past-year prevalence of psychiatric disorder.1,3–5 Second, there was a concurrent increase across migration groups in the use of mental health services, and this was not attributable to the increase in need for services. The increase in service use was weaker for guideline-concordant care than for any mental health care. Third, despite the increase in the relative likelihood of using services across migration groups, unmet need actually increased in absolute terms. Fourth, within Mexico there were associations between migration and mental health service use that have not been noted in previous research.

More than twice as many people in the third- or higher generation Mexican American group met criteria for at least 1 of the disorders assessed in this study as in either of the groups in Mexico. Although this increase occurred in all 3 categories of disorder, there was a difference in the pattern of change between mood and anxiety disorders on the one hand and substance use disorders on the other. The past-year prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders was higher among migrants than in the family members of migrants, but the prevalence of substance use disorders was lower in the migrants than in the family members of migrants. These findings extend those of Vega et al. who found that the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders was lower in immigrant than the US-born Mexican Americans.31 This pattern, which appears to result from a suppression of the prevalence of substance use disorder that is specific to the immigrant generation, is important to understand because there is evidence that substance use comorbidity complicates the treatment of psychiatric disorders.32

Use of services increased across migration groups in both the health care and the non–health care sectors. Within the health care sector the increase in mental health service use was attributable largely to the increase in use of general medical providers, and there was only a small and nonsignificant increase in the use of psychiatrist services. In the non–health care sector, there were increases across all provider types, including complementary–alternative medicine providers. There was no evidence that use of complementary–alternative medicine providers in Mexico33 was displaced by use of other types of providers in the United States.

The increase in use of mental health services was not solely attributable to the increase in need for services. After we adjusted for the severity of past-year disorders, Mexican Americans who were either born in the United States or spent part of their childhood in the United States were 2 to 3 times more likely than people in Mexico with no migrant in their family to use mental health services, both in the population as a whole and in the subsample with a past-year disorder. This finding implies that improvements in access to care or cultural changes in the disposition to seek care for mental health problems have positive effects on mental health service use in this population in the United States. Advancing understanding of the specific enabling and dispositional factors that result in increases in care in this population may inform strategies for further gains and contribute to reducing service use disparities across ethnic groups in the United States.

The apparent improvement in service use associated with migration was less consistent when we applied a minimum standard of quality of care. Among people who received care, the proportions receiving care that meets the minimum standard in Mexico and among Mexican Americans in the United States were similar to that for the United States as a whole, close to one third.34 One reason for the lack of improvement in receipt of minimally adequate care may be that the increase in care among Mexican Americans is largely attributable to care provided by general medical providers. Evidence suggests that patients are more likely to drop out of treatment and less likely to receive guideline-concordant care if they receive care from a general medical provider rather than a specialty mental health provider.34,35 It is striking that despite the vastly larger investment in mental health care in the United States, the net impact of changes in need for and use of services associated with migration to the United States is an increase in the prevalence of unmet need for care.

Within the population of Mexico, we found evidence that people in households in which there is a migrant were more likely to receive services if they have a disorder and less likely to receive minimally adequate care when they do, compared with people in households without a migrant. Additional research is needed to examine these relationships in greater detail. One reason for the increase in use of services may be the positive impact of migration on the household economic standing. Some of the income earned through migration may be invested in mental health care for other household members. The low likelihood of receiving adequate care may result from substance use comorbidity36; scarcity of economic resources to maintain a complete treatment, as much of the spending in health services in Mexico is out-of-pocket37; or from improved access to care providers who are unable to provide care that meets the standards of practice in the United States.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, only disorders assessed in both studies could be included in the analysis, contributing to an overestimate of the prevalence of service use among the population without a DSM-IV disorder.38–40 Second, to maintain adequate sample size for meaningful analysis, we used a definition of adequate treatment with a threshold substantially lower than standard practice guidelines. Third, we were not able to assess differences by type of service provider among respondents with a DSM-IV disorder, because even with the pooled data set we found too few cases to obtain stable estimates. Fourth, the data on service use were based solely on the self-report of the respondents; in the absence of confirmatory information on treatments, we could not assess the validity of these data or the possibility that mental disorders produce differential recall of service use. Fifth, data were gathered between 2001 and 2003. Because of subsequent changes in border control,41 deportation policy, and the rate of immigration,42 conditions for migrants in the United States may be substantially worse today than at that time. Finally, even though we found a statistically significant association of adequacy of treatment among 1.5- and second-generation compared with Mexicans with no migration experience in Mexico, this finding should be interpreted with caution because of the large CI in the estimation.

Conclusions

Use of mental health services was much more common among those meeting criteria for a past-year disorder than among those not meeting criteria for a disorder, supporting the validity of the diagnostic assessment as an indicator of need in both Mexico and the United States. There was also a portion of the population that used services without meeting criteria for a disorder, as has been found in studies of the US general population.34,40 A study of these apparent cases of “met unneed” has found that the large majority have one of several indications for treatment such as symptoms falling just short of a diagnostic threshold, continuing treatment of a previous disorder that is in remission, treatment of a condition that does not meet criteria for a disorder such as a suicide attempt, or services related to a disorder in a family member.43 In this study, the association between migration group and service use was similar in those with and without a past-year disorder.

This study confirms that Mexican immigrants and those of Mexican origin had higher prevalence of mental disorders compared with those in Mexico. Probably as a result, they quickly increase their use of services for mental and substance use disorders. Unfortunately, increased levels of adequacy of treatment that, overall, remained concernedly low did not follow this increase in service use. Research aimed to increase services, their adequacy, and allocation of scarce resources among the Mexican population and immigrants of this nationality is urgently needed.

Acknowledgments

Support for survey data collection came from funding provided by the National Institutes of Mental Health (grant R01 MH082023; J. B., PI).

Note. The funding organization had no interference on the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the article.

Human Participant Protection

The institutional review board from the National Institute of Psychiatry (Mexico City) approved this project. The institutional review boards of the Cambridge Health Alliance, the University of Washington, and the University of Michigan approved all recruitment, consent, and interviewing procedures for the National Latino and Asian American Survey. All study procedures were explained in the respondents’ preferred language, and written informed consent was obtained in the respondents’ preferred language. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication recruitment, consent, and field procedures were approved by the human participants committees of both Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan.

References

- 1.Alegría M, Canino G, Shrout PE et al. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant US Latino groups. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):359–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borges G, Breslau J, Su M, Miller M, Medina-Mora ME, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Immigration and suicidal behavior among Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):728–733. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.135160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borges G, Breslau J, Orozco R et al. A cross-national study on Mexico–US migration, substance use and substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breslau J, Borges G, Hagar Y, Tancredi D, Gilman S. Immigration to the USA and risk for mood and anxiety disorders: variation by origin and age at immigration. Psychol Med. 2009;39(7):1117–1127. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslau J, Borges G, Tancredi D et al. Migration from Mexico to the United States and subsequent risk for depressive and anxiety disorders: a cross-national study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(4):428–433. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Borges G et al. Mental disorders among English-speaking Mexican immigrants to the US compared to a national sample of Mexicans. Psychiatry Res. 2007;151(1-2):115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Orozco R, Fleiz C, Cherpitel C, Breslau J. The Mexican migration to the United States and substance use in northern Mexico. Addiction. 2009;104(4):603–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mental Health Atlas: 2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Woo M, Torres M, Gao S, Oddo V. Correlates of past-year mental health service use among Latinos: results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):76–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harman JS, Edlund MJ, Fortney JC. Disparities in the adequacy of depression treatment in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(12):1379–1385. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.12.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortega AN, Fang H, Perez VH et al. Health care access, use of services, and experiences among undocumented Mexicans and other Latinos. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(21):2354–2360. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C et al. Prevalence of mental disorders and use of services: results from the Mexican National Survey of Psychiatric Epidemiology [in Spanish] Salud Ment (Mex) 2003;26(4):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Haro JM, Heeringa SG, Pennell BE, Ustun TB. The World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2006;15(3):161–166. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00004395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alegria M, Takeuchi D, Canino G et al. Considering context, place and culture: the National Latino and Asian American Study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):208–220. doi: 10.1002/mpr.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute of Mental Health. Collaborative psychiatric epidemic surveys. 2010. Available at: http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/CPES. Accessed March 6, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harvard School of Medicine. The world mental health survey initiative. Available at: http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh. Accessed May 30, 2010.

- 22.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J. The World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291(21):2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O et al. Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMHCIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):122–139. doi: 10.1002/mpr.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Wang P, Lara C, Berglund P, Walters E. Treatment and adequacy of treatment of mental disorders among respondents to the Mexico National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(8):1371–1378. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.8.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang PS, Angermeyer M, Borges G et al. Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):177–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sturm R, Wells KB. How can care for depression become more cost-effective? JAMA. 1995;273(1):51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(1):55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.HEDIS 2000: Technical Specifications. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vega WA, Sribney WM, Achara-Abrahams I. Co-occurring alcohol, drug, and other psychiatric disorders among Mexican-origin people in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(7):1057–1064. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howland RH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR et al. Concurrent anxiety and substance use disorders among outpatients with major depression: clinical features and effect on treatment outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99(1-3):248–260. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tafur MM, Crowe TK, Torres E. A review of curanderismo and healing practices among Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Occup Ther Int. 2009;16(1):82–88. doi: 10.1002/oti.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olfson M, Mojtabai R, Sampson NA et al. Dropout from outpatient mental health care in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(7):898–907. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.7.898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. The effect of migration to the United States on substance use disorders among returned Mexican migrants and families of migrants. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1847–1851. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knaul FM, Arreola H, Borja C, Méndez O, Torres AC. The Social Protection System in Health From Mexico: Potential Effects Above Financial Justice and Catastrophic Household Expenditure. Health Kaleidoscope. Mexico City, Mexico: Fundación Mexicana para la Salud; 2003. [in Spanish] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J . Prevalence and severity of mental disorders in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. In: Kessler RC, Ustun TB, editors. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C et al. Prevalence, service use, and demographic correlates of 12-month DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in Mexico: results from the Mexican National Comorbidity Survey. Psychol Med. 2005;35(12):1773–1783. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Torres M, Polo A, Cao Z, Canino G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders across Latino subgroups in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):68–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. US Custom and Border Protection. Border Infrastructure System (BIS). 2010. Available at: http://www.cbp.gov/xp/cgov/border_security/ti/ti_projects/ti_bis.xml. Accessed August 28, 2012.

- 42. Passel J, Cohn D, Gonzalez-Barrera A. Net migration from Mexico falls to zero—and perhaps less. March 3, 2012. Available at: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2012/04/23/net-migration-from-mexico-falls-to-zero-and-perhaps-less. Accessed August 28, 2012.

- 43.Druss BG, Wang PS, Sampson NA et al. Understanding mental health treatment in persons without mental diagnoses: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1196–1203. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]