Abstract

Objectives. We estimated national trends of the prevalence of edentulism (complete tooth loss) for Asian American subgroups in the United States and investigated factors that could contribute to improvements in edentulism across populations over time.

Methods. We used 10 waves of the National Health Interview Survey data collected from 1999 to 2008. Eligible respondents were those aged 50 years and older who completed the question on tooth loss. We contrasted the odds and probabilities of edentulism over time in Chinese, Filipinos, Asian Indians, and other Asians with those in Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics.

Results. The rates of edentulism differed substantially across Asian subgroups. Compared with Whites, Chinese and other Asians had a lower risk of being edentulous, whereas being Filipino increased the odds. The rate for Asian Indians was similar to that for Whites. Nonetheless, rates of decline were similar across the Asian population groups.

Conclusions. Asian Americans are heterogeneous in edentulism. Innovative and sustainable public health programs and services are essential to prevent oral health diseases and conditions.

As a result of immigration and high fertility rates, Asian Americans are one of the fastest-growing segments of the US population, with an estimated growth rate from 2010 to 2011 of 2.2%, compared with 0.9% for the nation as a whole.1 However, Asian Americans are not a homogeneous group, but rather consist of a number of distinctly separate groups. Chinese Americans, estimated at 3.8 million in 2010, constitute 23% of Asian Americans, making them the largest ethnic group of Asian origin in the United States. They are followed by Asian Indians and Filipino Americans, who constitute 19% and 17% of the Asian population, respectively. Together, these 3 groups account for 60% of the Asian population in the United States.2 Most Asian Americans (69%) are immigrants,3 and they represent distinct cultural beliefs and customs, incomes, levels of education, geographic locations, religions, languages, immigration patterns, and levels of acculturation.

Despite the increasing numbers of Asian Americans from diverse backgrounds and experiences in the United States, very little is known about their oral health. Edentulism, or complete tooth loss, is one of the most important indicators of oral health. Edentulism reflects both the accumulated burden of oral diseases and conditions and the results of dental extraction treatment.4 Studies suggest that edentulism significantly affects quality of life, self-esteem, and nutritional status.5–8 According to national data, studies show that Asians have the lowest rate of edentulism among racial/ethnic groups in the United States.9,10 After adjustment for demographic characteristics and education, the rate of edentulism for Asians aged 50 years and older was 14.22% in 2008, lower than for many of the other racial/ethnic groups in the United States (for Blacks, 19.39%; Native Americans, 23.98%; Whites, 16.90%).10

Given the heterogeneity of the Asian population, further research on oral health across the subgroups of Asian Americans is warranted. Currently, research on oral health among Asian Americans is sparse. One study found that in New York City, Indian immigrants had a higher number of missing teeth and more periodontal disease than Chinese respondents.11 Another study conducted among low-income elderly residents in Seattle and Vancouver found that compared with White adults, Chinese immigrants had a higher risk of periodontitis.12 Although these studies provide useful information on oral health among Asian subgroups, the generalizability of the findings is limited by factors such as small sample size, nonprobability sampling design, and geographic constraints. To date, there are no national estimates of edentulism for Asian subgroups based on a nationally representative sample.

According to several studies, edentulism rates in the United States have declined for adult populations, including Asian Americans.10,13,14 However, these studies have left unanswered the question of whether this trend is consistent across subgroups of Asian American adult populations and, if not, what factors contribute to oral health disparities among the subgroups of older Asian Americans.

We examined the trend of edentulism among adults aged 50 years and older in 3 large Asian American ethnic groups (Chinese, Filipinos, and Asian Indians) and other Asians, compared with 3 major racial/ethnic groups in the United States (non-Hispanic Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics). Our objectives were (1) to estimate national trends of the prevalence of edentulism for Asian American subgroups in the United States and (2) to investigate factors that could contribute to improvements in edentulism across populations over time.

METHODS

We used the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), which is a cross-sectional household interview survey conducted annually. The main objective of the NHIS is to monitor the health of the US population through the collection and analysis of data on a broad range of health topics. The multistage area probability design provides a representative sample of the civilian noninstitutionalized population residing in the United States at the time of the interviews. We aggregated 10 waves of NHIS data collected from 1999 to 2008. Eligible respondents were those aged 50 years and older who completed the question on tooth loss.

Measures

Dependent variable.

To determine edentulism, we used self-reported responses to a question on whether the individual had lost all upper and lower natural teeth. We coded edentulism as 1 and otherwise as 0.

Independent variables.

We measured race/ethnicity using dichotomous variables for Asian Indians, Chinese, Filipinos, other Asians, Blacks, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic Whites. Time ranged from 1 to 10 as measured by the number of years of the NHIS data included in the study beginning in 1999.

Covariates.

The sociodemographic variables included age measured in years (50–85; age was top coded as 85), gender (1 = female, 0 = male), marital status (1 = married or living with partner, 0 = otherwise), and immigration status (1 = born in the United States, 0 = otherwise). We measured socioeconomic status (SES) by educational level (1 = 1st–11th grade, 2 = high school graduate, 3 = some college, 4 = bachelor’s degree, 5 = graduate or professional).

Health status included self-reported medical conditions, functional status, and memory problems. The medical conditions were measured by asking the respondents whether they had been told by a doctor that they had had a heart attack, coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, emphysema, asthma, or chronic bronchitis. For the analyses, we created the variable “lung disease” by combining emphysema, asthma, and chronic bronchitis into 1 medical condition variable. We treated each medical condition as a dichotomous variable. Functional status was measured by reported limitations in activities of daily living and limitations in the ability to complete routine activities, or instrumental activities of daily living. We calculated the activities of daily living scale as the sum (range = 0–6) of 6 self-reported items that asked about needing help eating, dressing, bathing, using the toilet, getting around in the home, and getting in and out of bed. We defined an instrumental activity of daily living, measured by a single item, as a dichotomous measure of whether respondents needed help with routine needs (1 = needed help with routine needs, 0 = otherwise). We measured memory problems by respondent’s report of being limited by difficulty remembering (1 = difficulty remembering, 0 = otherwise). We assessed self-reported smoking status (1 = current smoker, 0 = otherwise). We also included the presence or absence of dental insurance and time of last dental checkup as covariates.

Data Analysis

We used SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) to estimate logistic regression models for the effects of predictors on edentulism, a dichotomous dependent variable. To generate population prevalence estimates, we used a pooled survey weight in all analyses. We adjusted weighting for differential selection probabilities, missing data, and census-based age, race/ethnicity, and gender distributions at each time point. In supplemental analyses, unweighted models controlling for age, race/ethnicity, and gender produced near-identical results. To take sample stratification and clustering into account, we analyzed the data with SAS PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC and Stata SVY: LOGISTIC.

When testing time–race/ethnicity interactions, we centered time at the mean to reduce collinearity. Given our very large sample, and to adjust for multiple contrasts between Asian subgroups and other ethnic groups, we used a P value of .0025 (derived from a Bonferroni correction) to identify significant effects. Missing data were minimal, with missing values on individual items less than 2% and missing data across all items taken together at about 6%. We imputed 5 values for each missing data point using SAS PROC MI. We used SAS PROC MIANALYZE and Stata MI: ESTIMATE to estimate parameters and standard errors based on these multiple imputations.

We performed the following 2 sets of analyses.

Analysis 1: ethnic differences in the odds of edentulism averaged over time.

We used a hierarchical block design in multivariate analyses. The first logistic model included time, age, gender, and 6 dummy variables for race/ethnicity. In initial analyses, time squared was significant and added to the model, whereas race/ethnicity by time product terms were not significant and were excluded. We added education in model 2, marital status, smoking, and chronic conditions in model 3, and dental visits and dental insurance in model 4. Although we present results from model 1 and model 4 only, we used changes in the effects of race/ethnicity at each step in interpreting differences between model 1 and model 4.

Analysis 2: change in probability of edentulism over time.

Studies have shown that when the dependent variable is dichotomous, estimates of whether the effect of 1 risk factor varies across levels of another should be assessed on an additive scale (effects on the probability of disease) rather than on a multiplicative scale (effects on the odds of disease).15–17 After plotting the logistic-predicted probability of edentulism over time separately for each ethnic group, we used methods described by Landerman et al.18 and Mustillo et al.19 to test, on an additive scale, whether changes over time in the probability of edentulism varied by race/ethnicity.

RESULTS

Asian Americans exhibited distinct sociodemographic and health attributes compared with White, Black, and Hispanic Americans (Table 1). Compared with White, Black, and Hispanic respondents, a higher proportion of Asians were married, had dental insurance coverage, and had a college degree or above. The majority of Asians were immigrants. The percentage of those who were native born was 1.5%, 6.1%, 22%, and 30% for Asian Indians, Chinese, Filipinos, and other Asians, respectively. Asians had a lower rate of smoking than Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. Filipinos had the highest rate of hypertension of all ethnic groups except Blacks. Asian Indians had the highest rate of diabetes. Asians (except Filipinos) had a lower rate of lung disease than Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. The same was the case for the rate of edentulism. Filipinos had a higher rate of edentulism than Whites and Hispanics, but a lower rate than Blacks.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Aggregate Sample, by Racial/Ethnic Group: National Health Interview Survey, United States, 1999–2008

| Characteristics | Whitea (n = 87 088), Mean (SD) or % | Blackb (n = 15 392), Mean (SD) or % | Hispanic (n = 13 719), Mean (SD) or % | Asian Indian (n = 339), Mean (SD) or % | Chinese (n = 669), Mean (SD) or % | Filipino (n = 709), Mean (SD) or % | Other Asian (n = 1302), Mean (SD) or % |

| Sociodemographic | |||||||

| Age, y (range = 50–85) | 65.49 (10.77) | 63.65 (10.20) | 62.85 (9.85) | 60.46 (8.25) | 64.12 (10.68) | 62.79 (9.68) | 64.60 (10.64) |

| Female | 57.77 | 61.44 | 58.52 | 38.05 | 53.06 | 58.67 | 59.60 |

| Marriedc | 53.56 | 32.45 | 50.85 | 74.26 | 67.02 | 61.28 | 58.71 |

| Educational level | |||||||

| 1st–11th grade | 15.45 | 32.17 | 50.41 | 13.90 | 20.34 | 10.82 | 19.51 |

| High school graduate | 34.99 | 32.32 | 24.85 | 17.22 | 22.52 | 20.78 | 30.76 |

| Some college | 25.33 | 22.14 | 15.56 | 13.29 | 13.82 | 26.84 | 19.83 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 13.95 | 7.64 | 5.73 | 24.17 | 25.47 | 33.33 | 20.54 |

| Graduate or professional | 10.27 | 5.73 | 3.44 | 31.42 | 17.86 | 8.23 | 9.36 |

| Has dental insurance | 10.26 | 7.31 | 6.52 | 16.22 | 14.69 | 15.18 | 14.42 |

| Born in the United States | 95.24 | 93.38 | 40.86 | 1.47 | 16.59 | 21.72 | 30.19 |

| Health | |||||||

| Current smoker | 16.52 | 21.03 | 14.89 | 6.57 | 6.06 | 10.62 | 11.54 |

| ADL score (range = 0–6) | 0.09 (0.58) | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.41 (0.49) | 0.16 (0.37) | 0.14 (0.80) | 0.10 (0.63) | 0.10 (0.69) |

| IADL: routinely needs help | 8.34 | 12.82 | 9.44 | 3.54 | 7.62 | 6.06 | 6.91 |

| Memory problem | 4.95 | 8.44 | 6.90 | 2.36 | 6.59 | 4.24 | 5.15 |

| Heart attack | 8.14 | 6.67 | 6.14 | 5.31 | 2.10 | 5.93 | 3.84 |

| Coronary heart disease | 9.75 | 8.17 | 7.48 | 6.49 | 7.26 | 8.33 | 5.78 |

| Diabetes | 12.01 | 22.07 | 21.12 | 25.15 | 11.57 | 17.63 | 12.87 |

| Hypertension | 45.54 | 62.81 | 45.33 | 37.46 | 38.70 | 50.92 | 42.53 |

| Lung disease | 15.67 | 15.21 | 13.45 | 8.55 | 7.55 | 14.55 | 11.06 |

| Time since last dental checkup | |||||||

| Never had dental checkup | 0.27 | 0.81 | 2.20 | 3.35 | 2.94 | 0.58 | 1.97 |

| > 5 y | 17.66 | 24.47 | 20.96 | 9.45 | 10.82 | 13.15 | 12.23 |

| 2–5 y | 9.41 | 15.38 | 14.71 | 10.67 | 11.44 | 11.56 | 10.97 |

| 1– < 2 y | 9.10 | 14.21 | 13.73 | 14.94 | 9.43 | 11.71 | 11.44 |

| 6 mo– < 1 y | 14.07 | 16.6 | 16.89 | 19.82 | 17.62 | 18.21 | 16.73 |

| < 6 mo | 49.49 | 28.54 | 31.52 | 41.77 | 47.76 | 44.8 | 46.65 |

| Edentulous | 18.85 | 22.12 | 16.60 | 10.71 | 11.76 | 20.06 | 13.20 |

Note. ADL = activity of daily living; IADL = instrumental activity of daily living.

White, Non-Hispanic.

Black, Non-Hispanic.

“Married” includes respondents who were either married or living with partner.

Ethnic Differences in the Odds of Edentulism Averaged Over Time

Model 1 in Table 2 gives the effects of race/ethnicity on the odds of edentulism, controlling for time, age, gender, and whether a respondent was born in the United States. The coefficient for time in model 1 indicates that, on average (at the centered mean on time), the odds of edentulism declined by 3% per year. The significant positive coefficient for time squared is evidence of steeper decline in the rate of edentulism at the start of the study, followed by a slower rate of decline.

TABLE 2—

Logistic Regression Effects of Race/Ethnicity on Edentulism Among Respondents Older Than 50 Years: National Health Interview Survey, United States, 1999–2008

| Model 1a |

Model 4b |

|||

| Variables | OR (99% CI) | P | OR (99% CI) | P |

| Intercept | 0.003 (0.003, 0.004) | < .001 | 0.075 (0.058, 0.096) | < .001 |

| Time | 0.970 (0.959, 0.980) | < .001 | 0.976 (0.965, 0.987) | < .001 |

| Time square | 1.006 (1.003, 1.010) | < .001 | 1.006 (1.002, 1.010) | < .001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White (Ref) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Black | 1.346 (1.243, 1.457) | < .001 | 0.751 (0.690, 0.818) | < .001 |

| Hispanic | 1.087 (0.974, 1.213) | .049 | 0.583 (0.508, 0.670) | < .001 |

| Asian Indian | 0.720 (0.460, 1.127) | .059 | 0.645 (0.372, 1.118) | .04 |

| Chinese | 0.610 (0.425, 0.876) | < .001 | 0.569 (0.355, 0.912) | .002 |

| Filipino | 1.578 (1.132, 2.200) | < .001 | 1.775 (1.187, 2.654) | < .001 |

| Other Asian | 0.736 (0.551, 0.984) | .007 | 0.727 (0.533, 0.992) | .008 |

| Born in the US | 1.115 (1.011, 1.228) | .004 | 1.013 (0.893 1.150) | .787 |

| Age | 1.062 (1.060, 1.065) | < .001 | 1.053 (1.050, 1.056) | < .001 |

| Female | 1.026 (0.979, 1.075) | .157 | 1.115 (1.051, 1.182) | < .001 |

| Education | 0.748 (0.727, 0.769) | < .001 | ||

| Married | 1.004 (0.946, 1.066) | .866 | ||

| Health | ||||

| Smoker | 1.816 (1.678, 1.965) | < .001 | ||

| ADL | 0.997 (0.955, 1.040) | .839 | ||

| IADL | 1.116 (1.005, 1.238) | .007 | ||

| Memory problem | 1.155 (1.026, 1.300) | .002 | ||

| Heart attack | 1.201 (1.079, 1.337) | < .001 | ||

| Coronary heart disease | 1.110 (1.000, 1.233) | .01 | ||

| Diabetes | 1.296 (1.203, 1.396) | < .001 | ||

| Hypertension | 1.100 (1.040, 1.163) | < .001 | ||

| Lung disease | 1.345 (1.249, 1.449) | < .001 | ||

| Dental insurance | 0.824 (0.711, 0.955) | < .001 | ||

| Last dental checkup | 0.511 (0.501, 0.522) | < .001 | ||

Note. ADL = activity of daily living; CI = confidence interval; IADL = instrumental activity of daily living; OR = odds ratio. The total sample size was n = 119 442.

Model 1 controls for time, age, gender, and being born in the United States. Models 2 and 3 were intermediate models where education, marital status, smoking, and health were added sequentially to the regression equation.

Model 4 adds controls for dental insurance and dental visits.

Blacks, Hispanics, and Filipinos all had increased odds of edentulism compared with Whites, with the largest increase associated with being Filipino, which increased the odds by 58%. Being Chinese lowered the odds of edentulism by 39%, whereas the other Asians group had a 26% lower odds. The odds for Asian Indians were not significantly different from those for Whites. Additional contrasts (not shown) indicated that the odds of edentulism for Chinese (odds ratio [OR] = 0.61) and other Asians (OR = 0.74) were significantly lower than for Blacks (OR = 1.35) and Hispanics (OR = 1.09), whereas the odds for Asian Indians (OR = 0.72) were significantly lower than for Blacks (P < .001). Filipinos had significantly higher odds of edentulism (OR = 1.58) than Asian Indians, Chinese, other Asians, Whites, and Hispanics, but not Blacks. Older respondents and those born in the United States were at increased risk of edentulism.

In model 4, we included controls for education, marital status, smoking, physical health, dental insurance, and time since last dental visit. Odds of edentulism remained significantly lower for Chinese Americans than for Whites (OR = 0.57), and similar trends were evident for Asian Indians (OR = 0.65) and other Asians (OR = 0.73). With the additional covariates, Blacks and Hispanics had lower rates of edentulism than Whites. We conducted additional analyses using Blacks and Hispanics as a reference group (instead of Whites) to contrast the differences between the estimated odds of these 2 groups and Asian Indians, Chinese, and other Asians (data not shown). The results of these comparisons were no longer significant. In these analyses, Filipinos had a significantly higher edentulism rate than all other racial/ethnic groups.

Changes in Probability of Edentulism Over Time

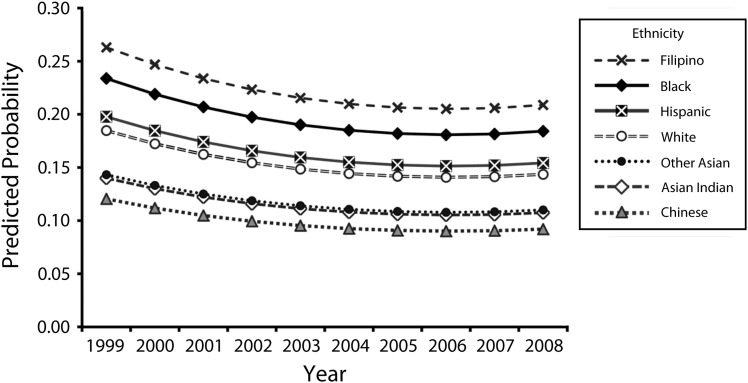

We generated the predicted probabilities of edentulism from a logistic model, with edentulism predicted by time, time squared, age gender, and birth status. The data show a decline between 1999 and 2005 (from 19% in 1999 to 15% in 2005) and a leveling off between 2005 and 2008 (not shown). Overall, the predicted probability of edentulism declined by about 4% over 10 years. For Figure 1 (based on model 1, Table 2), we added race/ethnicity (dummied) to the predictive model, and calculated separate changes in the probability of edentulism by race/ethnicity from the logistic model. In general, the predicted probabilities showed different baseline values by race/ethnicity but similar patterns of decline, with perhaps slightly less decline among Whites, other Asians, Asian Indians, and Chinese. This impression is confirmed in Table 3, which shows substantial racial/ethnic differences in 1999 and 2008 but a similar rate of decline (between 0.3% and 0.5% per year) in all racial/ethnic groups.

FIGURE 1—

Changes in the logistic-predicted probability of edentulism, by racial/ethnic group: National Health Interview Survey, United States, 1999–2008.

TABLE 3—

Overall Change in the Logistic-Predicted Probability of Edentulism, by Time and Race/Ethnicity: National Health Interview Survey, United States, 1999–2008

| Predicted Probability |

|||

| Race/Ethnicity | 1999 | 2008 | Change |

| White | 0.185 | 0.144 | −0.041 |

| Black | 0.234 | 0.184 | −0.050 |

| Hispanic | 0.198 | 0.154 | −0.044 |

| Asian Indian | 0.140 | 0.107 | −0.033 |

| Chinese | 0.121 | 0.092 | −0.029 |

| Filipino | 0.263 | 0.209 | −0.054 |

| Other Asian | 0.143 | 0.110 | −0.033 |

DISCUSSION

Using the NHIS, we found that the edentulism rate for middle-aged and older Asian Americans declined in the period from 1999 to 2008, although the decline was slower in recent years (after 2005). The rates substantially differed across Asian subgroups, and they remained significant after controlling for population heterogeneity (i.e., SES, health behaviors, physical health, function status, and regular dental checkups). Compared with Whites, Chinese and other Asians had a lower risk of being edentulous, whereas Filipinos had a higher risk. For Asian Indians, the rate was similar to that of their White counterparts. Comparing the rate of change in edentulism, our study showed that there was a similar rate of decline for the 4 Asian population groups.

Previous studies have reported that Filipino Americans have a high prevalence of diabetes and hypertension than non-Hispanic Whites.20–22 The association between these health conditions and oral health may be a product of shared risk factors, such as lifestyle and diet. Some evidence suggests that the Filipino diet may contain relatively greater amounts of fat and cholesterol than that of other Asian Americans because of frequent consumption of fried foods, pastries and other dessert goods, soft drinks, and high-fat snack foods.23 Specifically, high sugar intake, associated with consumption of fatty foods, may negatively affect oral health among Filipino American adults. For this reason, diet may contribute to the significantly higher rate of both deleterious health conditions and edentulism among Filipino Americans compared with Whites and other racial/ethnic groups.

Cultural beliefs and prior dental experience may also be contributing factors. Findings from one study showed that Filipino parents and younger immigrants associated fear and other negative attributes with dental care, because of previously painful experiences and the routine extraction of teeth for dental problems during visits to the dentist in the Philippines.24 Although our analyses controlled for dental care use, the higher rate of edentulism among Filipino Americans may derive from a negative cultural attitude toward dental visits and inadequate regular use of preventative dental care for some Filipinos. Given the paucity of research on oral health among Filipinos, further research is warranted to investigate oral health status and its related risk factors in this segment of the population.

Our study found that Chinese Americans had a significantly lower rate of edentulism than did other racial/ethnic groups, including Whites, Hispanics, and Blacks. This finding differs from those of 2 previous studies, which found that Chinese Americans had worse clinical oral health and poorer oral health–related quality of life than Whites.12,25 These variations could be attributed to the different sampling data collection methods. These previous studies used convenience samples and the data were collected in either Mandarin or Cantonese for Chinese Americans. The Chinese participants had a lower level of income and education than their White counterparts. In our study, we used a nationally representative sample of individuals in the United States; however, only those individuals who spoke English were included in the sample. Thus, the NHIS sample likely excluded many immigrants with low SES, low access to dental care, and poor oral health status since oral health and SES is highly correlated.

Our study found that Asian Indians are more homogenous than Chinese Americans regarding immigrant history and SES. Although Asian Indians had a lower risk of edentulism than Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics, these differences were not significant when population heterogeneity was controlled. Asian Indians were the youngest and had the highest SES (as measured by education, income, and dental coverage). These characteristics are positive factors related to oral health. On the other hand, 99% of the Asian Indians were immigrants, a higher rate than for other racial/ethnic groups. Immigrants were less likely to become edentulous. Nonetheless, this correlation was no longer significant when SES, health status, and health behaviors were taken into account. The finding suggests that rather than immigrant status alone, the many characteristics associated with being an immigrant affect health status. Immigrants bring with them particular cultural values and attitudes, health behaviors, dietary practices, and biological characteristics that, along with their exposure to environmental and sociopolitical factors, may influence their oral health.

Our study found that edentulism has continued to decline for major Asian American subpopulations and other major racial/ethnic groups in the United States. This finding is consistent with previous studies of edentulism among adult populations collected in earlier time periods (from the 1970s to 2004) and across major racial/ethnic groups in the United States.9,13,14,26 Our study found that education and dental checkups are negatively associated with edentulism, whereas smoking increases the risk. Previous studies have attributed the declining edentulism rate to the decrease in smoking, increasing years of education, and more regular use of preventive dental care among more recent cohorts.13,27 Many other factors for which data were not available in this study could also contribute to the decreased edentulism rate, such as the introduction of fluoridation through community water treatment28and fluoridated toothpaste and mouth rinse.29,30 Health practices such as use of dietary supplements and professionally applied or prescribed gel, foam, and varnish may also contribute to improved tooth retention.28,30,31 Others point to advancements in dental technologies and treatment modalities, changes in patient and provider attitudes and treatment preferences, improved oral hygiene, and regular use of dental services.7,32

It is worth noting that in model 1, Blacks and Hispanics had a higher risk of being edentulous than Whites. Blacks and Hispanics were less educated, more likely to smoke and have chronic health problems, and less likely to have had a recent dental visit. After we controlled for lower education, more chronic conditions, and fewer dental visits, Blacks and Hispanics had significantly lower rates of edentulism than did Whites. In addition, when we controlled for these covariates, the rates of edentulism for Blacks and Hispanics became similar to those of Asian subgroups (except for Filipinos, who still had a significantly higher rate of edentulism than other groups). The results suggest that the disparities in edentulism for Blacks and Hispanics, in contrast to the majority of the Asian groups and Whites, can be explained by an individual’s SES, health status, and dental care. These findings suggest that interventions to improve oral health should not be limited to improving dental care for minority populations, but that SES, health conditions, and health behaviors should also be improved.

Limitations

There are some limitations inherent in the NHIS survey data. The survey was conducted only in English; individuals who did not speak English were more likely to have lower SES and thus be at higher risk of poor oral health. The sample was drawn from the community-dwelling population, which excluded individuals residing in institutions (e.g., nursing homes or other long-term care facilities). It is likely that many unmeasured factors, such as dietary behaviors, oral health knowledge, cultural beliefs and practices toward oral health, and quality of dental care, play a role in edentulism.32,33

Conclusions

There was a downward trend in edentulism rates between 1999 and 2008 for all racial/ethnic groups. The rates of edentulism differed substantially across Asian subgroups. Although the rate of change differed across the Asian subpopulations, the differences were small. Given the increasing numbers of adults retaining their natural teeth—who have a higher risk of dental caries and periodontal diseases—interventions designed to assist individuals in maintaining healthy teeth become more critical. Innovative and sustainable public health programs and services are essential for the prevention of oral disease among elderly populations in general and minority populations in particular. Examples include working with interdisciplinary teams to develop dental care delivery models to meet the diverse needs of older Americans; implementing effective and inexpensive preventive services at clinical and community sites by local outreach to older adults; encouraging stakeholders to participate in creating policies and organizational changes that support healthy behaviors; improving oral health knowledge by launching a national education and awareness program for older adults; and developing new methods and technologies (e.g., nontraditional settings, nondental professionals, new types of dental professionals, and telehealth) to improve access of dental care for older adults.34–37

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (1R01DE019110).

We thank Xiao Luo for his assistance in data management.

Human Participant Protection

This research protocol was approved by the Duke University institutional review board.

References

- 1.Mather M. What’s driving the decline of US population growth? Population Reference Bureau. 2012. Available at: http://www.prb.org/Articles/2012/us-population-growth-decline.aspx. Accessed December 6, 2012.

- 2.Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO, Shahid H.The Asian Population: 2010 Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census; March 20122010 Census Briefs [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Rise of Asian Americans. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; July 12, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders AE, Slade GD, Carter KD, Stewart JF. Trends in prevalence of complete tooth loss among Australians, 1979–2002. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28(6):549–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2004.tb00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowjack-Raymer RE, Sheiham A. Association of edentulism and diet and nutrition in US adults. J Dent Res. 2003;82(2):123–126. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Social impact of oral conditions among older adults. Aust Dent J. 1994;39(6):358–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1994.tb03106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starr JM, Hall R. Predictors and correlates of edentulism in healthy older people. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13(1):19–23. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328333aa37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polzer I, Schimmel M, Müller F, Biffar R. Edentulism as part of the general health problems of elderly adults. Int Dent J. 2010;60(3):143–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoenborn CA, Heyman KM. Health characteristics of adults aged 55 years and over: United States, 2004–2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009;(16):1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu B, Liang J, Plassman BL, Remle C, Luo X. Edentulism trends among middle-aged and older adults in the United States: comparison of five racial/ethnic groups. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40(2):145–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2011.00640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz GD, Chen Y, Salazar CR, Le Geros RZ. The association of immigration and acculturation attributes with oral health among immigrants in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(suppl 2):S474–S480. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Persson GR, Persson RE, Hollender LG, Kiyak HA. The impact of ethnicity, gender, and marital status on periodontal and systemic health of older subjects in the Trials to Enhance Elders’ Teeth and Oral Health (TEETH) J Periodontol. 2004;75(6):817–823. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.6.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunha-Cruz J, Hujoel PP, Nadanovsky P. Secular trends in socio-economic disparities in edentulism: USA, 1972–2001. J Dent Res. 2007;86(2):131–136. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V et al. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Vital Health Stat 11. 2007;(248):1–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahlbom A, Alfredsson L. Interaction: a word with two meanings creates confusion. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20(7):563–564. doi: 10.1007/s10654-005-4410-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufman JS. Interaction reaction. Epidemiology. 2009;20(2):159–160. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318197c0f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TW. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Williams and Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landerman LR, Mustillo SA, Land KC. Modeling repeated measures of dichotomous data: testing whether the within-person trajectory of change varies across levels of between-person factors. Soc Sci Res. 2011;40(5):1456–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mustillo S, Landerman LR, Land KC. Using marginal effects to test slope differences in mixed Poisson models. Sociol Methods Res. 2012;41:467–487. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langenberg C, Araneta MR, Bergstrom J, Marmot M, Barrett-Connor E. Diabetes and coronary heart disease in Filipino-American women: role of growth and life-course socioeconomic factors. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(3):535–541. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Report to the President and the Nation. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: Addressing Health Disparities: Opportunities for Building a Healthier America. Washington, DC: President’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders; 2003. xv, 92, 93. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan C, Shaw R, Pliam M et al. Coronary heart disease in Filipino and Filipino-American patients: prevalence of risk factors and outcomes of treatment. J Invasive Cardiol. 2000;12(3):134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen K. Health and dietary issues affecting Asians. CA Department of Public Health, CA department of Health Care Services, InterAgency Nutrition Coordinating Council. 2008. Available at: http://www.dhcs.ca.gov/dataandstats/reports/Documents/CaliforniaFoodGuide/0Preface.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2013.

- 24.Hilton IV, Stephen S, Barker JC, Weintraub JA. Cultural factors and children’s oral health care: a qualitative study of carers of young children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35(6):429–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swoboda J, Kiyak HA, Persson RE et al. Predictors of oral health quality of life in older adults. Spec Care Dentist. 2006;26(4):137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2006.tb01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu B, Plassmam BL, Liang J, Landerman L, Beck JD. Cognitive function and oral hygiene behavior in later life. Paper presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference; July 14–19, 2012; Vancouver, British Columbia.

- 27.Eklund SA. Changing treatment patterns. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130(12):1707–1712. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adair SM, Bowen WH, Burt BA et al. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50(RR–14):1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Featherstone JD. Prevention and reversal of dental caries: role of low level fluoride. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1999;27(1):31–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1999.tb01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marthaler TM. Changes in dental caries 1953–2003. Caries Res. 2004;38(3):173–181. doi: 10.1159/000077752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weyant RJ. Seven systematic reviews confirm topical fluoride therapy is effective in preventing dental caries. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2004;4(2):129–135. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Truman BI, Gooch BF, Sulemana I et al. Reviews of evidence on interventions to prevent dental caries, oral and pharyngeal cancers, and sports-related craniofacial injuries. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(1 suppl):21–54. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00449-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slack-Smith L, Lange A, Paley G, O’Grady M, French D, Short L. Oral health and access to dental care: a qualitative investigation among older people in the community. Gerodontology. 2010;27(2):104–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2009.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamster IB. Oral health care services for older adults: a looming crisis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):699–702. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gooch BF, Malvitz DM, Griffin SO, Maas WR. Promoting the oral health of older adults through the chronic disease model: CDC’s perspective on what we still need to know. J Dent Educ. 2005;69(9):1058–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; and National Research Council2011 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamster IB, Northridge ME. Improving Oral Health for the Elderly: An Interdisciplinary Approach. New York, NY: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]