INADEQUATE WATER AND sanitation facilities pose a major impediment to school-going girls during menstruation, compromising their ability to maintain proper hygiene and privacy. A growing focus on menstrual hygiene management (MHM) from nongovernmental organizations, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and other international agencies now highlights the profound impact of this problem on school-aged girls and provides the basis for a much needed research, programming, and policy agenda.

MENSTRUATION AND SCHOOLGIRLS IN LOW-INCOME COUNTRIES

Every day, schoolgirls in low-income countries around the world discover blood on their underwear for the first time, feel an uncomfortable cramping in their lower abdomen, and find themselves in a setting without toilets, water, or a supportive female teacher to explain the change happening in their body. Cultural taboos and secrecy about menstrual blood compound this problem. Despite growing local and global attention to MHM and its impact on girls, significant knowledge gaps persist.

The fact that a normal bodily function such as menstruation commonly interrupts a girl’s ability to participate in school and progress academically is a problem long overdue for attention and resources. An appropriate and just response to this complex issue requires a range of research and programming options and collaboration across the social sciences, urban planning, water, sanitation, and health and education disciplines.

UNHEALTHY, UNSUPPORTIVE ENVIRONMENTS

Inadequate water and sanitation facilities pose a major impediment to school-going girls during menstruation, compromising their ability to maintain proper hygiene and privacy. More than half the schools in low-income countries lack sufficient latrines for girls and female teachers.1 Where latrines do exist, they are frequently unclean, too few in number, and unsafe. Toilets are often without doors, and girls are subject to harassment by boys.2 Water, even when available, is often located at a distance from the latrine stall, making it impossible for girls to privately wash blood off their hands and skirts before rejoining their classmates. Facilities also lack adequate means for disposal of used sanitary materials.3,4 Girls report dreading the idea of leaving signs of menstrual blood inside the latrine.3

Many girls lack adequate supplies of sanitary materials (and even underwear) and are forced to manage menses as best they can with cloth, tissues, or toilet paper.3 In some locales, girls have been reported to simply skip school during monthly menses rather than face the possibility of an embarrassing menstrual leak in the classroom or teasing by their classmates.5,6

REFRAMING A LONG-NEGLECTED ISSUE

For decades, MHM has been overlooked while the population health community understandably has focused its attention on issues related to adolescent girls’ sexual and reproductive health, such as risks from HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, family planning, and contraceptive use. A growing focus on MHM from nongovernmental organizations, UNICEF, and other international agencies now highlights the profound impact of this problem on school-aged girls and provides the basis for a much needed research, programming, and policy agenda.

Definition of Menstrual Hygiene Management

| Women and adolescent girls are using a clean menstrual management material to absorb or collect blood that can be changed in privacy as often as necessary for the duration of the menstruation period, using soap and water for washing the body as required, and having access to facilities to dispose of used menstrual management materials |

A review of the scholarly and gray literature over the past 15 years reveals the degree to which girls across a range of local cultures are unable to manage their menses safely, comfortably, and knowledgeably. In 2001, the Rockefeller Foundation supported a series of case studies exploring the sexual maturation of schoolgirls in Uganda, Zimbabwe, Kenya, and Ghana.7,8 Girls across all four countries reported inadequate sanitation facilities, lack of guidance on menstrual management, and a male-dominated teaching staff that made asking for support difficult. More recent research documenting stories from low- and middle-income schoolgirls in Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Nepal, and India reveals a range of difficulties in managing menses in school environments.4–6,9–12

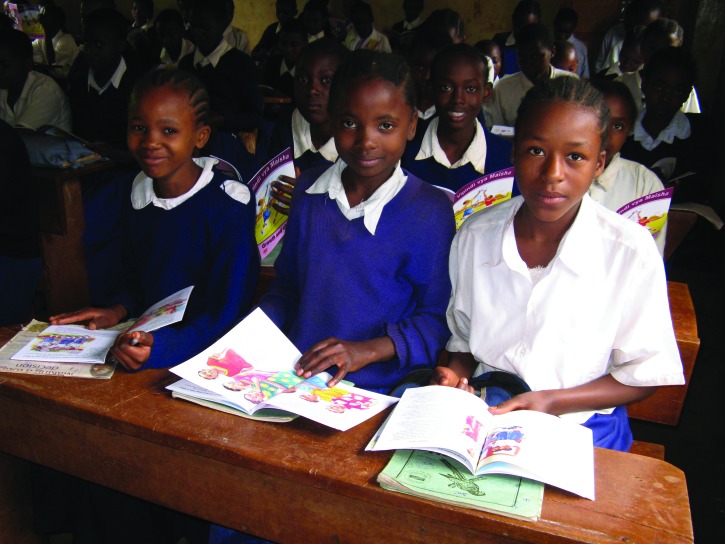

Tanzania girls reading the puberty book. Photograph by Marni Sommer.

Sierra Leone girls reading the puberty book developed through support from the United Nation's Children's Fund (UNICEF). Printed with permission of UNICEF.

The home environment proves to be yet another challenge for girls. Although public health experts have assumed that girls receive pubertal-related guidance from parents or extended family, an increasing body of research suggests that in fact they often learn nothing about menarche before its onset and may even hide the arrival of their first menstrual period for fear of being punished for perceived sexual activity.3,12

A CALL FOR MORE SUBSTANTIAL RESEARCH

The growing attention paid to MHM reveals important gaps in research methodology and content. The majority of the MHM evidence to date, which focuses on obstacles and adverse conditions faced by girls and female teachers and their recommendations for improving MHM in schools, has been collected through qualitative and participatory methodologies.13 Although these approaches are appropriate because of the sensitive nature of this health issue, the information they provide is not sufficient, considering the limited availability of donor and government resources.

Acceptable Menstrual Hygiene Management Facilities

| • Provide privacy for changing materials and for washing the body with soap and water. |

| • Provide access to water and soap in a place that provides an adequate level of privacy for washing stains from clothes and reusable menstrual materials. |

| • Provide access to disposal facilities for used menstrual materials (from collection point to final disposal). |

Elevating this issue requires quantitative evidence of interventions that have effectively enhanced girl’s participation, self-efficacy, performance, and school attendance. Although such data can be sensitive and difficult to obtain (school attendance, for example, can be challenging to measure because of poor school recordkeeping, variability of girls’ menstrual cycles, and variability in student self-reporting), creative approaches for gathering accurate attendance and other quantitative measures are possible and should be incorporated into future research conducted on MHM. More comprehensive and perhaps creative analysis will be essential to determine the most cost-effective and efficient means of addressing MHM in schools.

ADVANCING THE AGENDA FOR MENSTRUAL HYGIENE MANAGEMENT

Despite the limited programmatic and policy response to MHM to date, a growing global movement is focusing attention and resources on this issue. Significant developments in the past year signal a much-needed change of pace and lay the groundwork for future efforts. For example, the first ever conference on MHM for Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Schools, cohosted by Columbia University and UNICEF, united more than 200 MHM researchers, programmers, and policymakers working globally to address MHM barriers facing schoolgirls. UNICEF country offices in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, South East Asia, and Latin America presented research on their early efforts to address barriers to MHM in collaboration with country education systems.14 Challenges facing schoolgirls in humanitarian emergency contexts were also highlighted, along with new findings from an Emory University–UNICEF collaborative study on MHM in schools in four countries.15,16 In addition, a decision by the Joint Monitoring Program of the World Health Organization and UNICEF to advocate for the inclusion of MHM into the post-2015 sustainability goals initiated a series of discussions resulting in a clear and unified definition for MHM (see the sidebar on p. e2) and acceptable MHM facilities (see the sidebar on p. e3).17

Promising efforts currently under way include a new publication titled Menstrual Hygiene Matters, which represents the first effort to provide in-depth guidance to MHM practitioners in the development and humanitarian fields.18 There are also girl’s puberty books being published in Tanzania, Ghana, Cambodia, Sierra Leone, India, Zimbabwe, and elsewhere14,19; advocacy by the Forum for African Women Educationalists to remove value-added tax on the import of sanitary materials into sub-Saharan African countries; and numerous social entrepreneurial efforts to produce low-cost, environmentally safe sanitary materials. Most recently, on March 8, 2013, International Women’s Day, the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council convened a global meeting on womanhood and MHM in Geneva, Switzerland, bringing together a range of stakeholders to discuss moving forward the MHM agenda more broadly.

Experts must build on this momentum and continue to understand the impact of MHM on girls’ ability to learn and thrive in the school setting. A multisectoral response encompassing water, sanitation, urban planning, education, health, and social science disciplines can ensure that appropriate, evidence-based, and cost-effective interventions and policy are developed and implemented, and that girls and women ultimately use them. As with other sensitive or taboo topics, responses must be culturally and locally based and adapted. From the perspective of both human rights and public health, every menstruating girl and woman should have a safe, clean, and private space in which to manage monthly menses with dignity.20

References

- 1. United Nations Children’s Fund. Raising Clean Hands. New York, NY; 2012.

- 2. Kirk J, Sommer M. Menstruation and body awareness: linking girls’ health with girls’ education. Royal Tropical Institute. 2006. Available at: http://www.kit.nl/smartsite.shtml?ch=fab&id= 5582. Accessed October 12, 2012.

- 3. Emory University; United Nations Children’s Fund, Bolivia. Presentation at: Menstrual Hygiene Management Virtual Conference; September 29, 2012. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/wash/schools. Accessed November 28, 2012.

- 4. McMahon SA, Winch PJ, Caruso BA, et al. “The girl with her period is the one to hang her head”: reflections on menstrual management among schoolgirls in rural Kenya. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011;11(7):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Mahon T, Fernandes M. Menstrual hygiene in South Asia: a neglected issue for WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) programs. Gend Dev. 2010;18(1):99–113.

- 6. Montgomery P, Ryus C, Dolan C, Dopson S, Scott L. Sanitary pad interventions for girls’ education in Ghana: a pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10): e48274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. Stewart J. Life Skills, Maturation, and Sanitation: What’s (Not) Happening in Our Schools? An Exploratory Study From Zimbabwe. Harare, Zimbabwe: Women’s Law Center Weaver Press; 2004.

- 8. Kirumira E, ed. Life Skills, Maturation, and Sanitation: What’s (Not) Happening in Our Schools? An Exploratory Study From Uganda. Harare, Zimbabwe: Women’s Law Center Weaver Press; 2004.

- 9. Crofts T, Fisher J. Menstrual hygiene in Ugandan schools: an investigation of low-cost sanitary pads. J Water Sanitation Hygiene Dev. 2012;2(1):50–58.

- 10. Fehr AE. Stress, Menstruation and School Attendance: Effects of Water Access Among Adolescent Girls in South Gondar, Ethiopia[master's thesis]. Atlanta, GA: Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University; 2011.

- 11. Sommer M. Where the education system and women’s bodies collide: the social and health impact of girls’ experiences of menstruation and schooling in Tanzania. J Adolesc. 2009;33(4):521–529. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12. Sommer M, Mokoah Ackatia-Armah N. The gendered nature of schooling in Ghana: hurdles to girls’ menstrual management in school. JENdA. 2012;20: 63–79.

- 13. Sommer M. Putting “menstrual hygiene management” into the school water and sanitation agenda. Waterlines. 2010;29(4):268–278.

- 14. Sommer M, Vasquez E, Worthington N, Sahin M. WASH in schools empowers girls' education: proceedings of the menstrual hygiene management in schools. United Nations' Children's Fund, Columbia University. 2013. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/wash/schools/files/WASH_in_Schools_Empowers_Girls_Education_Proceedings_of_Virtual_MHM_conference.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2013.

- 15. United Nations Children’s Fund. WASH in Schools. Available at: http://www.unicef.org/wash/schools. Accessed November 28, 2012.

- 16. Sommer M. Menstrual hygiene management in humanitarian emergencies: gaps and recommendations. Waterlines. 2012;31(1–2):83–104.

- 17. WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme. Meeting Report of the JMP Post-2015 Global Monitoring Working Group on Hygiene. Washington, DC; May 15–16, 2012.

- 18. House S, Mahon T, Cavill S. Menstrual Hygiene Matters: A Resource for Improving Menstrual Hygiene Around the World. London, UK: WaterAid; 2012.

- 19. Sommer M. An early window of opportunity for promoting girls’ health: policy implications of the girl’s puberty book project in Tanzania. Int Electron J Health Educ. 2011;14:77–92.

- 20. United Nations. The human right to water and sanitation. Available at: http://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/human_right_to_water.shtml. Accessed November 28, 2012.