Abstract

We reviewed methods of studies assessing restaurant foods’ sodium content and nutrition databases. We systematically searched the 1964–2012 literature and manually examined references in selected articles and studies.

Twenty-six (5.2%) of the 499 articles we found met the inclusion criteria and were abstracted. Five were conducted nationally. Sodium content determination methods included laboratory analysis (n = 15), point-of-purchase nutrition information or restaurants’ Web sites (n = 8), and menu analysis with a nutrient database (n = 3).

There is no comprehensive data system that provides all information needed to monitor changes in sodium or other nutrients among restaurant foods. Combining information from different sources and methods may help inform a comprehensive system to monitor sodium content reduction efforts in the US food supply and to develop future strategies.

IN THE UNITED STATES, MORE than 90% of the population consumes excess sodium relative to guidelines (< 2300 mg overall and 1500 mg for specific populations).1–3 In 2007–2008, an estimated 25% of sodium intake among the US population was from foods obtained at restaurants.3 On any given day, an estimated 53% of the US population consumed at least 1 food or beverage item from a restaurant.4 Average total daily intake of sodium from all foods was higher for individuals who consumed at least 1 food from a restaurant (3623 ±71 mg) than among those who did not (2999 ±58 mg).4 The greater contribution of restaurant foods to sodium intake may be attributable to the food types consumed, a greater amount of sodium in restaurant foods than in versions of these foods made at home, or the consumption of larger portions. Monitoring the nutrient content and other characteristics (e.g., serving size) of restaurant foods may aid the development of strategies to reduce sodium intake.3

Because the vast majority of sodium intake is estimated to come from packaged and restaurant foods, efforts to reduce the sodium content of these foods are ongoing.5–9 Monitoring the sodium content of packaged foods is feasible because of the Nutrition Facts label that can be found on packaged foods and the availability of public and private databases containing this information.10 At present, data on the sodium content of restaurant foods are more limited. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommends the monitoring of sodium in the US food supply5 because excess sodium intake is a major preventable risk factor for high blood pressure, a leading cause of heart disease and stroke.11 The IOM indicated that the substantial contribution to the nation’s sodium intake made by restaurants and items provided by food services warrants the monitoring of the sodium content of restaurant foods.2,5,12

To date, several groups have assessed the nutrient content of foods from fast-food and other restaurants in the United States and other countries.7,13–16 However, the wide range of restaurant types and foods consumed from these establishments, combined with the lack of public and private databases incorporating nutrient values for these foods, presents a challenge to the development of national monitoring systems and has prompted calls for better methods to monitor and track restaurant foods.10,17

We reviewed studies assessing the sodium content of restaurant foods in the United States and other countries to help inform the development of a US national monitoring system. Our objectives were (1) to identify the strengths and limitations of the methods that have been used to select restaurants and foods as well as the measures and methods used to assess sodium content, and (2) with the information from this review, to evaluate the utility of current US nutrient and restaurant databases for building a national system to monitor the sodium content of restaurant foods.

METHODS

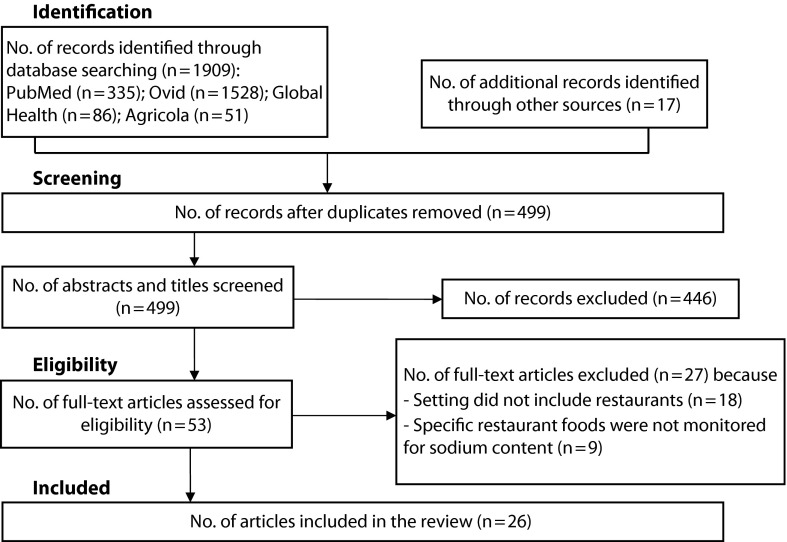

We used a search strategy, developed in consultation with a medical librarian, to identify articles related to sodium monitoring in restaurant foods (Table 1). The electronic databases we employed were PubMed (from January 1, 1964 to December 31, 2012), Agricola, Global Health, and Ovid (including Books at Ovid, Embase, GeoRef, and MEDLINE). Medical Subject Headings (MeSH terms), developed by the National Library of Medicine, included “sodium”; “sodium, dietary”; “sodium chloride”; “diet, sodium-restricted”; “food services”; and “restaurants” (Table 1). We manually screened the reference lists of the articles ultimately included in this study for any additional articles. In addition, we used the Thomson Reuters Web of Knowledge to search for other articles that cited each included article. Figure 1 describes the flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses.18

TABLE 1—

Search Strategy to Identify Articles Related to “Sodium Monitoring in Restaurant Foods” From January 1, 1964 to December 31, 2012, on PubMed

| Step | Terms | No. of Articles |

| 1 | Sodium (text word) OR sodium (MeSH term) | 413 530 |

| 2 | Sodium, dietary (MeSH term) | 7226 |

| 3 | Sodium chloride (MeSH term) or salt (text word) | 185 943 |

| 4 | Diet, sodium-restricted (MeSH term) | 5705 |

| 5 | 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 | 503 447 |

| 6 | Food services (text word) | 20 098 |

| 7 | Food services (MeSH term) | 10 898 |

| 8 | Restaurants (MeSH term) OR restaurants (all fields) | 3375 |

| 9 | 6 OR 7 OR 8 | 21 043 |

| 10 | 5 AND 9 | 443 |

| 11 | 10 and limit to humans | 335 |

Note. MeSH = Medical Subject Heading developed by National Library of Medicine.

FIGURE 1—

Flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review for studies that assessed the sodium content of restaurant foods, January 1, 1964 to December 31, 2012.

Inclusion Criteria

To be included in the review, each article needed to satisfy the following criteria:

Include methods for assessing the nutrient content of restaurant foods within a specific geographic area. We excluded the following food services: child care centers and schools, food establishments not open to or accessible by the general public (such as private clubs), food catering, and packaged food from grocery stores.

Include measurement of sodium content by specific food types (e.g., pizza, hamburgers).

After removal of duplicates, we identified a total of 499 articles fitting the MeSH terms. Initially, 2 authors (J. M. and M. E. C.) independently screened the title and abstract of each identified article. An article was excluded with no further review if both reviewers indicated that it did not meet the inclusion criteria. If the abstract contained any indication of relevance to the review as assessed by either reviewer or when its relevance was unclear (n = 53), the same 2 authors screened the full article independently. These authors discussed and resolved any discrepancy in the assessment of whether an article should be included. In all, 26 articles met the inclusion criteria, including 24 journal publications, 1 book chapter,15 and 1 report19 (Figure 1). For practical purposes, we now refer to all as “studies.”

Data Extraction

From the 26 studies, authors J. M. and M. E. C. abstracted the following data: first author, publication year, level (national, county, local), geographic location, time period of evaluation, restaurant number and type as specified by the authors of each study (e.g., fast food), selection of food (e.g., menu items) and number assessed, and food categories reported.

For restaurant type, we used the term reported in each study, as we could find no standard definition of restaurant types in the literature. In addition, we abstracted data on sodium measures reported, and other nutrients and food components monitored, nutrient analysis methods, and food categorization methods. Finally, we abstracted data on restaurant coverage (that is, the percentage of restaurants within a specific geographic area or the percentage of market share or market sales within a specific geographic area represented by the restaurant[s] being studied), and the purpose of the study (data not reported in the tables).

RESULTS

The 26 studies published between 1973 and 2012 included 14 studies conducted in the United States,14,15,19–30 1 in multiple countries,16 and 11 international studies31–41 (Table 2). Only 5 studies were conducted at the national level.14,15,19,31,32

TABLE 2—

Study Characteristics, Methods Used for Selecting Restaurants and Foods, and Food Categorization in Studies That Assessed the Sodium Content of Restaurant Foods, January 1, 1964 to December 31, 2012

| Food Categories Reported |

||||||

| Author, Year | Level (Location) | Time | Restaurants Selected, No. and Type | Selection of Foods | Main Categories Description (No.) | Food Categorization Methods |

| US studies | ||||||

| Wu and Sturm, 201314 | National | Feb–May 2010 | 400 top chain restaurantsa | 30 923 menu items (29 531 regular and 1392 children’s) | Main entrée, appetizer, side dish, salads, salad dressing, soup, nonalcoholic beverages, desserts and baked goods (8) | All menu items served |

| NSRI, NYC Health Dept, 201019 | National | Feb 2009 | 50 largest QSR chains | NA | Breakfast, burgers, chicken, breaded seafood, sandwiches, pizza, Mexican (burritos, tacos), potatoes, soup, bakery products (25) | Identification of 25 menu item categories that were key contributors to sodium intake |

| Jacobson and Hurley, 200215 | National | NA | QSR, table service, coffee shop, ice cream, frozen desserts—total number NA | “Typically” 15 dishes from each restaurant | Breakfast, sandwiches, Chinese, Italian, pizza, Mexican, Greek, seafood, steakhouse, family style, dinner house, pastry and desserts, fast food, mall food (NA) | 15 or so “most popular” dishes in a given cuisine type, including 2 “relatively nutritious” dishes regardless of whether they were among the top 15 dishes |

| Bruemmer et al., 201220 | County (King County, WA) | May–Jul 2009, May–Jul 2010 | 37 chains (11 SD, 26 QSR)b | 3941 menu items | Entrée, appetizer, side dish, dessert, beverage, condiment (6) | Main type of food served |

| Britt, 201121 | City–county (City of Tacoma–Pierce County, WA) | Jun 2007– Sep 2008 | 24 locally owned restaurantsc | Average of 75 menu items per restaurant | Pizza, deli, Thai, café, diner, ready-made meals to cook at home, pub, Italian, American, Mexican, bar and grill (NA) | Main type of food served |

| Boutelle et al., 201122 | Local (San Diego, CA) | Sep–Nov 2008 | 1 FF restaurantd | NA (receipts from 368 adults with 492 children) | NA (NA) | Items listed in the restaurant menu that represented meals containing > 200 kcal |

| Johnson et al., 201023 | Local (NYC, NY) | Mar–Jun 2007 | 11 FF chainse | 6580 receipts (meals) | NA (NA) | Main type of food served |

| O’Donnell et al., 200824 | Local (Houston, TX) | Jul 2007 | 10 FF chainsf | 1146 meals (51 040 meals combination), 114 menu items per chain | Burger, chicken, deli, other (tacos, cheese dogs, cheese sandwiches) (NA) | Entrée component |

| Sarathy et al., 200825 | Local (Cleveland, OH) | Jan–Mar 2007 | 15 FF chainsg | 967 (804 entrées and 163 side dishes), 64 menu items per chain | NA (NA) | Entrées and side dishes |

| Root et al., 200426 | Local (NA) | NA | 2 FF restaurants | 2 menu items per chain (2 items sampled from 2 locations) | Taco and burrito (4) | NA |

| Green and Appledorf, 198327 | Local (Gainesville, FL) | 6 mo (year NA) | 5 table-service steak restaurants | 30 samples: 1 meal per restaurant per month for a total of 6 mo | 1 meal composed of NY strip sirloin steak, baked potato, bread, and salad with dressing (4) | Representative meal served in steak restaurants |

| Appledorf and Kelly, 197928 | Local (Gainesville, FL) | 6 mo (year NA) | 6 FF restaurants | 115 food items | Pizza, Mexican-American fast foods (taco, burrito, frijoles), submarine sandwiches (9) | NA |

| Appledorf, 197429 | Local (Gainesville, FL) | NA | 3 FF restaurantsh | Total of 15 samples, 5 menu items per restaurant, 3 samples of each item | Burgers, french fries, vanilla shake (5) | Main type of food served |

| Donovan and Appledorf, 197330 | Local (Gainesville, FL) | NA | 6 franchise food outlets | Total of 30 samples (5 samples per restaurant) | Chicken, coleslaw, bread, potato (4) | Main type of chicken dinner served |

| International (non-US) studies | ||||||

| Chand et al., 201231 | National (New Zealand) | Dec 2010–Jan 2011 | 12 FF chains (24 restaurants)i | 1126 food products | Breakfast, burgers, chicken, pasta, pizza, salads, sandwiches, seafood, side dishes, dessert, beverages, other (12) | Literature32 |

| Dunford et al., 201032 | National (Australia) | June 2009 | 9 FF chainsj | 580 (386 entrées, 33 side dishes, 27 breakfast) 39 menu items per chain | Breakfast, burgers, chicken products, pizza, salads, sandwiches, side dishes (7) | Literature24 and products grouping used by industry |

| Dunford et al., 201216 | Local in 6 countriesk | April 2010 | 6 FF chainsk | 2124 food items | Breakfast, burgers, chicken, pizza, salads, sandwiches, french fries (7) | Literature24,32 |

| Greenfield et al., 198433 | Local (Sydney, Australia) | 1983 | 12 takeout, 1 FF restaurant | 10 food items | Fried foods (potato chips, potato scallops, battered fish, battered hotdog, fish cakes), sandwiches (18) | Foods selected to compare with previous analyses42 |

| Wills et al., 198134 | Local (Sydney, Australia) | NA | 4 Lebanese, 4 Chinese, 4 fried takeout | 21 Lebanese foods, 29 Chinese foods, 14 takeout foods | Lebanese: bread, appetizers, entrees, desserts, set menu, mixed plate, combination meal (24) | Food most frequently ordered by customers based on customer surveys |

| Chinese: chicken, beef, pork, duck, fish, lobster, crab- and prawn-based foods, fried rice (29) | ||||||

| Takeout: potato chips, potato scallops, battered fish, fish cakes, fish cocktail, sausage, battered saveloy, spring roll, dim sum, crumbed chicken (14) | ||||||

| Wills and Greenfield, 198035 | Local (Sydney, Australia) | NA | 1 FF chain (4 restaurants)l | 16 foods | Burgers, fish filet, chicken and fries, french fries, apple pie, cookies, thick shake, sundae (16) | Main type of food served |

| Park et al., 200936 | Local (Seoul, Korea) | Jan 2009 | 10 cafeterias, 4 takeout | 79 meals or dishes (58 meals + 21 entrées) | Cafeteria: buffet-style meals: rice, soup, 2–3 side dishes, kimchi (21) | “Appears to be as workers would normally eat” |

| Takeout: 1-dish meal (rice dishes, wheat dishes, soups) (42) | ||||||

| Musaiger et al., 200837 | Local (Manama, Bahrain) | NA | FF outlets—no. NA | 27 samples, 9 foods per restaurant | Burgers, chicken nuggets, hotdog, roast beef sandwich, french fries (10) | Main type of food served |

| Musaiger et al., 200738 | Local (Manama, Bahrain) | NA | 3 food outlets | 61 samples | Samosa, sandwiches, grilled chicken, grilled meat, grilled beef, potato chops (9) | Main type of food served |

| Musaiger et al., 200739 | Local (Manama, Bahrain) | NA | 14 FF restaurants | 61 samples | Fast food of local origin: skewers (chicken, meat), grilled chicken or meat, sandwiches, samosa | Main type of food served |

| Fast food of Western origin: burgers, chicken, chicken nuggets, pizza (16) | ||||||

| Hassan et al., 199040 | Local (Kuwait City and Hawali, Kuwait) | NA | 5 FF restaurants | 100 samples, 20 foods (5 samples per food) | Sandwiches, filled dough, samposa (20) | Main type of local fast foods consumed by Kuwaiti population |

| Al-Khalifah, 199341 | Local (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) | NA | 4 takeout restaurants | 10 dishes | NA (10) | NA |

Note. FF = fast food; NA = not available; NSRI = National Salt Reduction Initiative; NYC = New York City; QSR = quick-service restaurant; SD = sit-down. The electronic databases we employed were PubMed, Agricola, Global Health, and Ovid (including Books at Ovid, Embase, GeoRef, and Medline).

The top-400 US chain restaurants by sales, based on the 2009 list of Restaurants & Institutions magazine.43 Restaurants included fast food, fast casual, buffet, family style, upscale, and takeout or delivery.

All chains n = 37: sit-down chains n = 11, quick-service chains n = 26 (6 burger chains, 9 pizza chains, 6 sandwich/submarine, and 5 Tex–Mex).

Twenty-four out of 600 locally owned restaurants in the city of Tacoma, Pierce County, Washington. Included 11 restaurants with 0–25 seats and 14–62 menu items, 6 restaurants with 26–74 seats and 24–108 menu items, and 7 restaurants with ≥ 75 seats and 50–180 menu items.

One McDonald’s restaurant located in a children’s hospital.

Licensed NYC fast-food chains providing public nutrition information as of March 1, 2007 (excluding coffee and ice cream chains). The 11 fast-food chains (in 167 locations) were Burger King, McDonald’s, Wendy’s, Au Bon Pain, Subway, KFC, Popeye’s, Domino’s, Papa John’s, Pizza Hut, and Taco Bell.

National or regional fast-food companies offering kids’ meals in Houston (fast-food meals that are boxed or bagged, often with a toy, and marketed to young children). The 10 fast-food companies (477 locations) were Arby’s, Burger King, Chick-fil-A, KFC, McDonald’s, Sonic, Subway, Taco Bell, Wendy’s, and Whataburger.

Fast-food restaurants with at least 10 chains in the Greater Cleveland area. A restaurant was considered a fast-food establishment if it met at least 2 of the following 4 criteria: (1) a permanent menu board was provided to select and order food, (2) customers paid for food before consuming it, (3) a self-service condiment bar was provided, and (4) most main-course food items were prepackaged rather than made to order. The 15 fast-food chains were Arby’s, Boston Market, Brueggers, Burger King, Dairy Queen, Domino’s, Dunkin’ Donuts, KFC, McDonald’s, Panera, Papa John’s, Pizza Hut, Subway, Taco Bell, and Wendy’s.

Burger King, McDonald’s, and Super Chef.

Burger Fuel, Burger King, Burger Wisconsin, Domino’s, Hell Pizza, KFC, McDonald’s, Muffin Break, Pizza Hut, Starbucks, Subway, Tank Juice.

Fifteen fast-food chains were identified through the National Retail Association of Australia. The 9 that provided product-specific nutrition information on their Web sites were included in the study: McDonald’s, Hungry Jack’s, Oporto, KFC, Red Rooster, Pizza Hut, Domino’s, Eagle Boys, and Subway.

Six fast-food chains operating in 6 countries (Australia, Canada, United States, France, New Zealand, United Kingdom): Burger King, McDonald’s, KFC, Domino’s, Pizza Hut, Subway.

Four McDonald’s restaurants in Sydney.

The main purpose of most studies (n = 23) was to evaluate the nutritional quality of food purchased at different restaurants: US chain restaurants,14,15 quick-service restaurant chains or fast food,15,16,19,20,22–26,28–33,35–40 chicken dinners,30 steak restaurants,27 Lebanese,33 Chinese,33 and takeout.33,34,36,41 Other cited purposes were to assess the feasibility of voluntary menu labeling among locally owned restaurants,21 evaluate the accuracy of claims that specific restaurant entrées were healthy,26 and assess the relative contribution of salt added by food handlers to the total sodium content of takeout foods.33 The number of chains or restaurants per study ranged from 1 to 400. None of the national studies included independent restaurants.

The majority of studies (n = 18) did not specify a measure of restaurant coverage (data not shown). In 4 studies, restaurant coverage was measured as the percentage represented by the study restaurant(s) of the restaurants within a specific geographic area,20,21,24,25 and in 4 other studies as a percentage of the total market share accounted for by the restaurants within a specific geographic area.14–16,32 One local study randomly selected 300 restaurants from major fast-food chains across approximately 1625 eligible locations in the 5 boroughs of New York City23 to evaluate the sodium content of lunchtime meals purchased. After the exclusion of 2 coffee shop chains from the analysis, 6580 purchases from 167 restaurants, representing 11 fast-food chains23 were evaluated (Table 2).

The selection of food included total meals, appetizers, entrées, side dishes, desserts, beverages, and breakfast food (Table 2). The food categories reported varied according to the individual study’s purpose, the location, and restaurant type. The majority of studies categorized their food based on the main type of food served in the restaurants (n = 18) or on foods frequently ordered by the consumers of the establishment(s) (n = 4); 3 studies did not specify how they chose the food categories (Table 2). The most common food categories assessed in the studies were sandwiches (n = 12), burgers (n = 9), chicken (n = 9), and pizza (n = 7). Among studies specifying food categories, the number of categories analyzed ranged from 4 to 67 (median = 10; Table 2).

As reported in Table 3, the sodium measure reported in the studies included total sodium in milligrams (n = 15) or parts per million (n = 2), milligrams per 100 grams (n = 13), milligrams per 1000 calories (n = 1), and specific categories of sodium content (e.g., < 800 mg per meal to meet the National School Lunch Program criteria24; n = 3). Most studies (n = 23) measured other nutrients and food components as well as sodium, with the most common being energy and fat (n = 20), carbohydrates or sugar (n = 17), and potassium (n = 13; Table 3). The methods used for determining the sodium content of restaurant foods included laboratory analysis (n = 15), nutrition content at point of purchase or as listed on the restaurants’ Web site (n = 8), and menu analysis with a nutrient database or computerized nutrition analysis program (n = 3; Table 3). The studies that included laboratory analyses typically sampled and analyzed small numbers of foods compared with those studies that used publicly available nutrition information or software for menu analysis.

TABLE 3—

Sodium Measures, Other Nutrients and Food Components Monitored, and Methods Used in Nutrient Analyses in Studies That Assessed the Sodium Content of Restaurant Foods, January 1, 1964 to December 31, 2012

| Author, Year | Sodium Measure Monitored | Other Nutrients and Food Components Monitored | Nutrient Analysis Methods |

| US studies | |||

| Wu et al., 201314 | mg | Energy, fat, CHO, protein | Restaurant’s Web site |

| NSRI, NYC Health Dept, 201019 | mg, mg/100 g | Energy, fat, chol, sugar, fiber | Restaurant’s Web site, market share data |

| Jacobson and Hurley, 200215 | mg | Energy, fat, chol, sugar | Laboratory analysis |

| Bruemmer et al., 201220 | mg | Energy, saturated fat | Point of purchase, Web site |

| Britt et al., 201121 | mg | Energy, fat, CHO | Menu analysisa |

| Boutelle et al., 201122 | mg | Energy, fat, chol, fiber | Menu analysis |

| Johnson et al., 201023 | mg, mg/1000 calories, sodium categories/mealb | None | Restaurant’s Web site |

| O’Donnell et al., 200824 | < 800 mg/meal | Energy, fat, CHO, sugar, protein, vitamins A and C, Ca, Fe | Menu analysisc |

| Sarathy et al., 200825 | < 900 mg/entrée < 300 mg/side dish | K, P | Restaurant’s Web site |

| Root et al., 200426 | mg | Energy, fat | Laboratory analysis |

| Green and Appledorf, 198327 | mg, mg/100 g | Energy, fat, CHO, fiber, protein, K and other mineralsd | Laboratory analysis |

| Appledorf and Kelly, 197928 | mg, mg/100 g | Energy, fat, CHO, fiber, protein, K and other mineralsd | Laboratory analysis |

| Appledorf, 197429 | mg, mg/100 g | Energy, fat, CHO, fiber, protein, K and other mineralsd | Laboratory analysis |

| Donovan and Appledorf, 197330 | mg | Energy, fat, CHO, fiber, protein, K and other mineralsd | Laboratory analysis |

| International (non-US) studies | |||

| Chand et al., 201231 | mg | Energy, fat, sugar | Point of purchase, Web site |

| Dunford et al., 201032 | mg, mg/100 g | Energy, fat, sugar | Restaurant’s Web site |

| Dunford et al., 201216 | mg/100 g | None | Restaurant’s Web site |

| Greenfield et al., 198433 | mg/100 g | K | Laboratory analysis |

| Wills et al., 198134 | mg/100 g | K, Fe, Ca, Mg, Zn | Laboratory analysis |

| Wills and Greenfield, 198035 | mg/100 g | Energy, fat, chol, CHO, sugars, protein, K and other vitamins and mineralse | Laboratory analysis |

| Park et al., 200936 | mg, mg/100 g | None | Laboratory analysis |

| Musaiger et al., 200837 | ppm | Energy, fat, chol, CHO, fiber, protein, K and other mineralsf | Laboratory analysis |

| Musaiger et al., 200738 | ppm | Energy, fat, chol, CHO, fiber, protein, K and other mineralsf | Laboratory analysis |

| Musaiger and D’Souza, 200739 | mg/100 g | Energy, fat, chol, CHO, fiber, protein, K and other vitamins and mineralsf | Laboratory analysis |

| Hassan et al., 199040 | mg/100 g | Energy, fat, CHO, fiber, protein, K, and other mineralsf | Laboratory analysis |

| Al-Khalifah, 199341 | mg/100 g | Energy, fat, chol, CHO, fiber, protein, K and other mineralsf | Laboratory analysis |

Note. Ca = calcium; CHO = carbohydrate; chol = cholesterol; Cu = copper; Fe = iron; I = iodine; K = potassium; Mg = magnesium; Mn = manganese; NA = not available; NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NSRI = National Salt Reduction Initiative; NYC = New York City; P = phosphorus; ppm = parts per million; USDA = United States Department of Agriculture; Zn = zinc. The electronic databases we employed were PubMed, Agricola, Global Health, and Ovid (including Books at Ovid, Embase, GeoRef, and Medline).

Menu analysis by nutritionists using nutrient database (ESHA Research Food processor SQL).

Sodium categories per meal: mg/meal: ≤ 600, 601–1499, 1500–2299, ≥ 2300.

Menu analysis by nutritionists using nutrient database (USDA nutrient database, Nutrition Data System for Research [University of Minnesota], version 5.0).

Ca, P, Fe, Mg, Zn, Mn, Cu.

Ca, Fe, K, thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, vitamins A and C.

Ca, P, K, Mg, Fe, I, Cu, Zn; vitamins A, C, E, B1, B2, B6, B9, B12, and niacin.

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review we identified 26 studies that assessed the sodium content of restaurant foods. None of these studies serve as a potential model for a national system to monitor sodium content of restaurant foods. Few of the studies, even at the local level, included restaurants that were not part of a chain. A major limitation of all but one was the use of estimated versus measured sodium content. Other potential methodological limitations in the studies included (1) scope of the data, (2) lack of representativeness of restaurants and foods, (3) low sensitivity for identifying changes over time in the sodium content of the food supply, and (4) a lack of standards for reporting. The analysis that follows, by considering these issues in some detail, could help to inform the development of a national system to monitor the content of sodium and other nutrients in restaurant foods.

Scope of the Data

In the 5 studies conducted at a national level, the methods varied for analyses of the nutrients in restaurant foods. One national study used laboratory analyses15 and the other 4 studies used available nutrition information from restaurants (at point of purchase, on a Web site, or by request).14,19,31,32

Laboratory analyses, such as those provided by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) for the National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference,13 can capture a variety of nutrients for foods from independent and chain restaurants and thus allow for the tracking of changes in nutrients other than sodium. These could include nutrients (e.g., potassium, iodine) other than those currently required on the Nutrition Facts panel. Tracking of these additional nutrients in restaurant foods is important for understanding the potential health consequences of the reformulation of food products to reduce sodium. Laboratory analyses, however, are resource intensive, expensive, and less feasible for monitoring large numbers of food brands. The choice of restaurants and foods for sampling for laboratory analyses requires careful consideration of the feasibility for achieving sodium reduction through reformulation of products, how well the product represents a particular food category in terms of its sales and sodium content, and the contribution the food makes to overall sodium intake. The USDA uses market data to sample brands of restaurant foods and a national sampling plan to select restaurant foods for analyses44; the data are based on the largest restaurant brands, using revenue or national intake data or market research on popular restaurant foods. In addition, some data on independent restaurants are included for comparison purposes. Analyses of these foods are currently used to update the USDA’s National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference and could be part of a monitoring system.13

Using nutrition information obtained from restaurants is the least expensive method of assessing the nutrient content of foods. With the widespread adoption of menu labeling in chain restaurants,45 it will be an opportunity for the development of more widely available and less costly tools to analyze menus. The University of Minnesota Nutrition Data System for Research,46 for example, uses menu analyses with information from the USDA’s National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference13 on ingredients to provide nutrient information on 1700 menu items from 23 restaurant chains, but this information is not publicly available.47

However, some studies have shown discrepancies between published and measured nutrient content of restaurant foods.48,49 Potential explanations for these discrepancies include differences in stated versus actual portion size, the use of outdated nutrient information for the menu analysis, a lag in updating information in relation to changes in recipes or formulations of foods, and conducting analyses based on the raw ingredients, rather than the cooked products. For example, some companies might use data from their suppliers to assess the nutrient content of their cooked product without taking into account the losses in volume because of cooking or other food preparation.

Representativeness of Restaurants and Foods

The methods used to select restaurants and sentinel foods can affect how well a potential monitoring system represents the sodium content of restaurant foods or the amount of sodium consumed from eating those foods. In this review, only 31% of the studies (8 of 26) reported restaurant coverage (the proportion of restaurants included in the study within a specific geographic area or their market share). This lack of information limits the applicability of findings to sodium in the food supply.

None of the national studies included independent restaurants, and the proportion of sodium intake that comes from these independent restaurants is unknown. Section 4205 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 requires restaurants and similar retail food establishments with 20 or more locations to list information on calories for standard menu items on restaurant menus and menu boards, including drive-through menu boards.45 Therefore, the contribution of smaller chains and independent restaurants to sodium in the food supply and ultimately to sodium intake will be a challenge.

According to the National Restaurant Association, there are 960 000 restaurant and food service outlets in the United States.50 Of these, 278 000 (less than one third) would be covered by the new calorie labeling regulations, although the sales volume and related consumption for these establishments is unknown.51 In fact, we identified only 1 published study that assessed the sodium content of foods in locally owned restaurants.21 In 2007, the City of Tacoma–Pierce County Health Department launched SmartMenu, a restaurant menu-labeling project that recruited 24 locally owned restaurants to voluntarily post nutrition information (calories, fat, carbohydrates, and sodium) on their menus.21 The most significant cited barriers to posting nutrient information were the infrequent use of standardized recipes, low perceived customer demand for nutrition information, and the associated costs and resources required for laboratory analysis.21 Nutrition labeling on wholesale food service items (e.g., soup base) used as base ingredients may help restaurants, particularly locally owned restaurants, report nutrition information.5

Food selection also can affect how well a monitoring system will represent sodium in the food supply. In the included studies, a variety of methods were used to select the foods reviewed, including individual purchases, all foods available on the Web site, and market share. Knowledge of the contributions made by restaurant food to sodium intake, sales, or market share may allow improvements to be made in the representativeness of a proposed national database. In developing a national monitoring system, it is important that, as a group, the restaurants chosen and the foods selected for analysis be sufficiently representative of the situation in the United States as a whole.

Identifying Changes in Sodium Content

All but 120 of the studies in this review were onetime assessments and thus did not include longitudinal data that would allow for ongoing monitoring of sodium content or changes in the makeup of the food supply. Although longitudinal data are not yet available, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene–led National Salt Reduction Initiative (NSRI) intended to monitor changes in the sodium content of restaurant items in 2012 and 2014, with baseline figures collected in 2009, and was analyzing 2012 data at the time we were writing this article.7 For its 2009 baseline, the NSRI Restaurant Database7 drew on nutrition information accessed from the 50 largest chain restaurants’ Web sites19 and used information on market share as well. From the database NSRI makes only the sodium concentration values by food category publicly available.

The ability to successfully monitor changes in restaurant foods over time requires timely, accurate, and uniform reporting of sodium content and serving size for food items that are easily sorted by category to understand changes in sodium concentration. Measurement error because of inaccurate reporting of foods based on analyses of recipes or menus could lead to an inability to pick up trends in sodium content over time or to drawing erroneous conclusions.48

Standards for Reporting

Compiling and making accessible longitudinal data are particularly valuable if the data are collected in a uniform way (e.g., separating salad dressing from salads; pairing dipping sauces with chicken fingers). Having standard food categories is important for comparing sodium content and other nutrients across foods, restaurants, and geographic locations.52 Coding food by using standard food categories, such as those developed by the USDA53 or the National Cancer Institute,54 may allow for comparison of the sodium content of restaurant foods with packaged foods, which could help assess progress across food production sectors. Furthermore, having uniform food categories would facilitate the ability to sort restaurant items so as to more easily merge them with national data on intake and possibly with commercially available sales or market share data. This would allow sales by category or item to be used when one is assessing change in sodium content nationally or regionally.

The use of standard reporting formats (e.g., sodium concentration measured as mg/100 g of the food of interest) would facilitate comparisons across restaurant types, food categories, and specific foods. Sodium concentration and density (mg/kcal) have the advantages of allowing comparison across restaurants with different serving sizes and recipes and facilitating comparisons with categories of packaged foods. As an alternative, the use of sodium per serving (mg/serving) would help customers choose among various restaurant options. All metrics are needed, which means that any system to monitor sodium content in restaurant foods also should include the serving size in grams and calories per item. Therefore, the development of reporting standards for nutrition information by restaurant chains could help assess compliance with the national menu labeling45 and provide an important resource for monitoring sodium and other nutrient content.

Although our search strategy maximized the identification of relevant articles, we did not include nonpublished studies (gray literature) or studies assessing nutrients other than sodium. To address this issue, we expanded the literature search to include published articles assessing macronutrients and sugar content in restaurant foods; 2 additional relevant studies that were found were included in the Discussion section.46,49 Although we did not search databases of nonpublished studies, we hand-searched the references of all published articles for additional relevant studies (published and unpublished) to include in this review. Through this process we identified 6 studies that we included in the present review.15,19,28–31

Recommendations for Monitoring Sodium Content

As demonstrated by this review, a number of published studies have assessed the sodium content of restaurant foods, but only 1 met our requirements to include data for more than 1 time period. On a global basis, continued monitoring of foods served in major chains is planned.16,55 The various approaches used by researchers have strengths and weaknesses, but currently there is no comprehensive private or publicly available system that provides all of the information needed to monitor nutrient changes in restaurant foods across the United States. Thus, researchers have relied on a limited number of existing public or commercial data sources to monitor the nutrient content of the US food supply.5 These sources were designed independently with varying purposes, representativeness of restaurants, breadth and depth of measures, sample sizes, and costs, but they suggest ways to develop a national system to monitor the sodium content of restaurant foods.

A combination of methods appears most useful. First, a system could include the use of publicly available nutrition information (whether passively or actively collected) from restaurants required to post calorie information. Second, monitoring of selected or sentinel restaurant foods with laboratory analyses would enhance the quality, accuracy, and potential timeliness of systems to monitor the sodium content of restaurant foods. Third, requiring nutrition labeling for wholesale food items would help capture changes in the sodium content of commonly used ingredients in independent and chain restaurants.

As indicated by the IOM,5 monitoring sodium levels in US foods requires a timely, accurate, and sensitive publicly available system to assess restaurant foods for changes in their content of sodium and other variables or measures (such as calories, added sugar, and fat) and also to identify items that meet specific nutrition standards. The use of currently available nutrient databases such as the USDA’s National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference13 and its Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, the University of Minnesota’s Nutrition Data System for Research,46 and New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s NSRI Restaurant Database7 provide examples of how a national database could be created by using standard food categorization and reporting. The IOM recommends that USDA in cooperation with HHS “should develop approaches utilizing current and new methodologies and databases to monitor the sodium content of the total food supply.”5(p296) Such a system would help increase our understanding of restaurants’ reformulation of foods, introduction of new foods, and preparation techniques to address concerns about sodium and inform initiatives and strategies to reduce sodium in the US food supply and sodium intake. Reducing average population sodium intake by 400 milligrams per day could avert 28 000 deaths from any cause and save 7 billion health care dollars.56 Monitoring restaurant foods will help us evaluate progress toward population sodium reduction.

Acknowledgments

J. Maalouf was supported by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education Research Participation Programs at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The authors thank Jessica Leighton and Claudine Kavanaugh, US Food and Drug Administration, Office of Foods, for their thorough review of the original draft of the article.

Note. The CDC’s participation in the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education Research program is made possible by an agreement between the Department of Energy and CDC.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not needed because the study did not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th ed. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Usual sodium intakes compared with current dietary guidelines—United States, 2005–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(41):1413–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: food categories contributing the most to sodium consumption—United States, 2007–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(5):92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhodes D, Clemens JC, Adler ME, Moshfegh AJ. Nutrient intakes from restaurants: what we eat in America, 2007–2008. FASEB J. 2012;26(suppl):1005.1.

- 5.Henney JF, Taylor CL, Boon CS Institute of Medicine. Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Food and Drug Administration. Approaches to reducing sodium consumption; establishment of dockets: request for comments, data, and information. Fed Regist. 2011;76(179)

- 7.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. National salt reduction initiative. Available at: http://nyc.gov/health/salt. Accessed January 30, 2013.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sodium reduction in communities. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/programs/sodium_reduction.htm. Accessed January 22, 2013.

- 9.US Department of Health and Human Services. Million hearts. Available at: http://millionhearts.hhs.gov/index.html. Accessed January 3, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Ng SW, Popkin BM. Monitoring foods and nutrients sold and consumed in the United States: dynamics and challenges. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(1):41.e4–45.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):e21–e181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kant AK, Graubard BI. Eating out in America, 1987–2000: trends and nutritional correlates. Prev Med. 2004;38(2):243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. US Department of Agriculture National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. 2011. Available at: http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12354500/Data/SR24/sr24_doc.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2013.

- 14.Wu HW, Sturm R. What’s on the menu? A review of the energy and nutritional content of US chain restaurant menus. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(1):87–96. doi: 10.1017/S136898001200122X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobson M, Hurley M. Restaurant Confidential. New York, NY: Workman Publishing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunford E, Webster J, Woodward M et al. The variability of reported salt levels in fast foods across six countries: opportunities for salt reduction. CMAJ. 2012;184(9):1023–1028. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silver LD, Farley TA. Sodium and potassium intake: mortality effects and policy implications. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1191–1192. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine. National Salt Reduction Initiative Coordinated by the New York City Health Department. In: Henney JF, Taylor CL, Boon CS, editors. Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States, Appendix G. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. pp. 443–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruemmer B, Krieger J, Saelens BE, Chan N. Energy, saturated fat, and sodium were lower in entrées at chain restaurants at 18 months compared with 6 months following the implementation of mandatory menu labeling regulation in King County, Washington. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(8):1169–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Britt JW, Frandsen K, Leng K, Evans D, Pulos E. Feasibility of voluntary menu labeling among locally owned restaurants. Health Promot Pract. 2011;12(1):18–24. doi: 10.1177/1524839910386182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boutelle KN, Fannin H, Newfield RS, Harnack L. Nutritional quality of lunch meal purchased for children at a fast-food restaurant. Childhood Obes. 2011;7(4):316–322. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson CM, Angell SY, Lederer A et al. Sodium content of lunchtime fast food purchases at major US chains. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(8):732–734. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Donnell SI, Hoerr SL, Mendoza JA, Tsuei Goh E. Nutrient quality of fast food kids meals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(5):1388–1395. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarathy S, Sullivan C, Leon JB, Sehgal AR. Fast food, phosphorus-containing additives, and the renal diet. J Ren Nutr. 2008;18(5):466–470. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Root AD, Toma RB, Frank GC, Reiboldt W. Meals identified as healthy choices on restaurant menus: an evaluation of accuracy. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2004;55(6):449–454. doi: 10.1080/09637480400010415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green EM, Appledorf H. Proximate and mineral content of restaurant steak meals. J Am Diet Assoc. 1983;82(2):142–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Appledorf H, Kelly LS. Proximate and mineral content of fast foods. J Am Diet Assoc. 1979;74(1):35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Appledorf H. Nutritional analysis of foods from fast-food chains. Food Technol. 1974;28(4):50, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donovan WP, Appledorf H. Protein, fat and mineral analyses of franchise chicken dinners. J Food Sci. 1973;38(1):79–80. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chand A, Eyles H, Ni Mhurchu C. Availability and accessibility of healthier options and nutrition information at New Zealand fast food restaurants. Appetite. 2012;58(1):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunford E, Webster J, Barzi F, Neal B. Nutrient content of products served by leading Australian fast food chains. Appetite. 2010;55(3):484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenfield H, Smith AM, Wills RB. Salting of take-away foods at point of purchase. Hum Nutr Appl Nutr. 1984;38(3):211–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wills RBH, Maples J, Greenfield H. Composition of Australian foods. 7. Minerals in Lebanese, Chinese and fried take-away foods. Food Technol Aust. 1981;33(6):274–276. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wills RBH, Greenfield H. Composition of Australian foods. 3. Foods from a major fast-food chain. Food Technol Aust. 1980;32(7):363–366. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park HR, Jeong GO, Lee SL et al. Workers intake too much salt from dishes of eating out and food service cafeterias; direct chemical analysis of sodium content. Nutr Res Pract. 2009;3(4):328–333. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2009.3.4.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Musaiger AO, Al-Jedah JH, D’Souza R. Proximate, mineral and fatty acid composition of fast foods consumed in Bahrain. Br Food J. 2008;110(10-11):1006–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Musaiger AO, Al-Jedah JH, D’Souza R. Nutritional profile of ready-to-eat foods consumed in Bahrain. Ecol Food Nutr. 2007;46(1):47–60. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Musaiger AO, D’Souza R. Nutritional profile of local and western fast foods consumed in Bahrain. Ecol Food Nutr. 2007;46(2):143–161. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hassan AS, Kashlan NB, Al-Mousa ZA et al. Proximate and mineral compositions of local Kuwaiti fast foods. Ecol Food Nutr. 1991;26(1):37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Khalifah AS. Chemical composition of selected take-away dishes consumed in Saudi Arabia. Ecol Food Nutr. 1993;30(2):137–143. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wills RBH, Wimalasiri P, Greenfield H. Composition of Australian foods. 5. Fried take-away foods. Food Technol Aust. 1981;33(1):26–27. [Google Scholar]

- 43. The QSR Fifty. Available at: http://www.qsrmagazine.com/reports/top-50. Accessed May 24, 2013.

- 44.Trainer D, Pehrsson PR, Haytowitz DB et al. Development of sample handling procedures for foods under USDA’s National Food and Nutrient Analysis Program. J Food Compost Anal. 2010;23(8):843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.US Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. New menu and vending machines labeling requirements. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/LabelingNutrition/ucm217762.htm. Accessed January 23, 2013.

- 46. University of Minnesota Nutrition Data System for Research. 2011. Available at: http://www.ncc.umn.edu/products/database.html. Accessed June 2, 2012.

- 47.Schakel SF, Buzzard IM, Gebhardt SE. Procedures for estimating nutrient values for food composition databases. J Food Compost Anal. 1997;10(13):102–114. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Urban LE, McCrory MA, Dallal GE et al. Accuracy of stated energy contents of restaurant foods. JAMA. 2011;306(3):287–293. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sloan ME, Bell LN. Fat content of restaurant meals: comparison between menu and experimental values. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(6):731–733. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Restaurant Association. Restaurant industry sales turn positive in 2011 after three tough years. Available at: http://www.restaurant.org/News-Research/News/Restaurant-industry-sales-turn-positive-in-2011-af. Accessed January 9, 2013.

- 51.Food and Drug Administration. Labeling: nutrition labeling of standard menu items in restaurants and similar retail food establishments. Notice of proposed rulemaking. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/LabelingNutrition/UCM249276.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2013.

- 52.German RR, Lee LM, Horan JM, Milstein RL, Pertowski CA, Waller MN Guidelines Working Group Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50(RR-13):1–35. [PubMed]

- 53.Hoy MK, Goldman JD, Murayi T, Rhodes DG, Moshfegh AJ. Sodium intake of the US population: what we eat in America, NHANES 2007–2008. US Department of Agriculture, Food Surveys Research Group. 2011. Available at: http://www.ars.usda.gov/sp2userfiles/place/12355000/pdf/dbrief/sodium_intake_0708.pdf. Accessed January 6, 2013.

- 54.National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Risk factor monitoring and methods. sources of sodium among the US population, 2005–06. Available at http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/diet/foodsources/sodium. Accessed January 6, 2013.

- 55.The Food Monitoring Group. International collaborative project to compare and track the nutritional composition of fast foods. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(7):590–599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]