Abstract

Purpose

Deformable image registration (DIR) algorithms may enable multi-fraction dose tracking and improved treatment response assessment, but the accuracy of these methods must be investigated. This study introduces and evaluates a novel deformable 3D dosimetry system (Presage-Def/Optical-CT) and its application toward investigating the accuracy of dose deformation in a commercial DIR package.

Methods and Materials

Presage-Def is a new dosimetry material consisting of an elastic polyurethane matrix doped with radiochromic leuco dye. Radiological and mechanical properties were characterized using standard techniques. Dose-tracking feasibility was evaluated by comparing dose distributions between dosimeters irradiated with and without 27% lateral compression. A checkerboard plan of 5 mm square fields enabled precise measurement of true deformation using 3D dosimetry. Predicted deformation was determined from a commercial DIR algorithm.

Results

Presage-Def exhibited a linear dose response with sensitivity of 0.0032 ΔOD/(Gy·cm). Mass density is 1.02 g/cm3 and effective atomic number is within 1.5% of water over a broad (0.03–10 MeV) energy range, indicating good water-equivalence. Elastic characteristics were close to liver tissue, with Young’s modulus of 13.5–887 kPa over a stress range of 0.233–303 kPa, and Poisson’s ratio of 0.475 (SE=0.036). The Presage-Def/Optical-CT system successfully imaged the non-deformed and deformed dose distributions with isotropic resolution of 1 mm. Comparison with the predicted deformed 3D dose distribution identified inaccuracies in the commercial DIR algorithm. While external contours were accurately deformed (sub-millimeter accuracy), volumetric dose deformation was poor. Checkerboard field positioning and dimension errors of up to 9 and 14 mm respectively were identified, and the 3D DIR-deformed dose gamma passing rate was only γ3%/3mm=60.0%.

Conclusions

The Presage-Def/Optical-CT system shows strong potential for comprehensive investigation of DIR algorithm accuracy. Substantial errors in a commercial DIR were found in the conditions evaluated. This work highlights the critical importance of careful validation of DIR algorithms prior to clinical implementation.

INTRODUCTION

Recent controversy in the literature has highlighted the potential of deformable-image-registration (DIR) techniques, and also the challenges associated with verifying these approaches and ensuring accurate performance (1, 2). DIR algorithms have the potential to translate information between image sets of spatially deformed anatomy. There are two main avenues of application within the context of radiotherapy: dose-tracking and treatment response assessment through multi-modality image fusion. In dose-tracking, DIR algorithms deform dose calculated on different CTs (i.e., taken throughout a fractionated course of therapy or phases of a 4DCT) back to a reference dataset, and thereby track the cumulative dose delivered to anatomy in different states of deformation (3). This information is critical for adaptive radiation treatment approaches which compensate for under/over-dosing to optimize therapeutic efficacy. In treatment response assessment, DIRs are used to relate intra-treatment functional image data (e.g., PET metabolic activity) to pre-treatment images, thereby enabling clinical decisions on current treatment efficacy and whether modification is required to improve outcome. Several DIRs have been proposed, with equal applicability to both dose-tracking and treatment response assessment. Experimental validation of DIR models is a critical necessity before these methods may be used to inform clinical decision making (1).

Commonly employed DIR algorithms fall into the categories of splines (4), optical/diffusion algorithms (5), free-form algorithms (6), and biomechanical algorithms (7). Since the objective of non-biomechanical DIR algorithms is to match intensities without considering elastic properties, points may deform in non-physical ways in cases with limited landmarks. Biomechanical algorithms, while potentially more accurate because they account for physical properties, are also likely to have errors due to uncertainties in Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio inputs. In an evaluation of 21 DIR algorithms from different groups (8), lung errors at visible bronchial landmarks were as high as 5 mm in 12/21 algorithms, and maximum liver errors at visible vessel bifurcations were greater than 5 mm in all cases and as high as 1 cm in one case. A deformable lung phantom evaluated on 8 algorithms from 6 institutions showed that B-spline implementations can vary by as much as 15 mm (9). A commercial algorithm (Varian Medical Systems) applied to repeat prostate CT sets (10) to propagate contours via deformable registration resulted in unacceptable contours in 43% of cases for bladder and 66–83% of cases for rectum. Comparison (11) of 6 algorithms (1 surface, 3 B-splines, 2 non-parametric) on lung datasets in various phases showed that the match errors were low at highly visible bronchial bifurcations near the mediastinum. This is to be expected from algorithms specifically driven to match intensity landmarks. Match errors were higher at less visible landmarks.

The DIR validation methods described above typically assess deformation at a limited number of fiducial points, and cannot be considered a comprehensive evaluation. More comprehensive methods are highly desirable. One approach is to use 3D dosimetry techniques which capture dose under deformation, thus providing a physical distribution as a standard for comparison (12–14). A key advantage of 3D dosimetry is that the dose distribution itself can be used to spatially label and quantitatively track the ground truth of deformation in a deforming dosimeter. This labeling can be high-resolution (1 mm isotropic) and fully comprehensive in 3D, creating a uniquely powerful validation platform that compares ground truth with the calculations from DIR algorithms. Both Yeo et al. (14, 15) and Niu et al. (13) present 3D methodologies utilizing deformable polymer-based gel dosimeters, read out in the former case by optical computed tomography (optical-CT) and in the latter by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). There are disadvantages to MRI not only in terms of the inherent accuracy of the methodology, but also in terms of cost and accessibility (16, 17). Optical-CT is capable of high accuracy at low cost, but in the case of polymer gels, scatter effects limit the size of the dose distribution that may be evaluated without sophisticated corrections (18).

In this work we introduce a novel deformable 3D dosimeter, Presage-Def, which is characterized in terms of both radiological and mechanical properties. Presage-Def exhibits light-absorbing radiochromic contrast which facilitates accurate readout by optical-CT without need for complex scatter corrections (19, 20). Presage-Def is then applied to investigate the accuracy of a common commercial DIR for the limited case of dose deformation in a homogenous media.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Presage-Def deformable 3D dosimeter

PRESAGE® (Heuris Inc, Skillman, NJ) is an established rigid radiochromic 3D dosimeter consisting of a transparent polyurethane matrix (~80–90% of the dosimeter by weight), a triarylmethane leuco dye, and a trihalomethane initiator (19, 21). Manufacturing details have been previously published (22, 23), including in U.S. Patent Application Publication No. 2007/0020793A1. PRESAGE® has been validated as a dosimetry material with dose-rate independence, intra-batch reproducibility, temporal stability, tissue-equivalence, and linear response to dose (19, 21, 24). The new Presage-Def material is similar to PRESAGE® but with polyol replaced by polyether to create an elastic polyurethane matrix. Presage-Def has a density of 1.02 g/cm3 and contains 2% leuco dye by weight. Leuco dyes bis(N,N-dimethylamine)-o-methoxy-LMG (o-MeO-LMG) and 2,4-dimethyl-N,N-dimethylamine-LMG (dimethyl-LMG) were used in the formulations for this study. The effective atomic number (Zeff) was calculated with the power law method and as a function of energy using Auto-Zeff (RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia) (25), and compared to water to determine water-equivalence.

To characterize dose sensitivity Presage-Def material was poured into small volume optical cuvettes (1×1×4 cm). For mechanical characterization, Presage-Def was also cast in optical cuvettes, but then removed from the cuvettes to create unbounded small volume samples (9×9×25 mm). The DIR validation tests were performed on cylindrical Presage-Def dosimeters (6 cm diameter, 4.75 cm long) (Figure 1A). All irradiations were conducted on a 6 MV linac at 600 cGy/min. Dose sensitivity was determined from the change in optical density in cuvettes irradiated at 100 SSD and 5.5 cm depth in a 30×30×11 cm block of solid water to known doses between 0–8 Gy. Change in optical density was measured using a Spectronic Genesys 20 spectrophotometer and determined by subtracting the pre-irradiation absorption from the post-irradiation absorption for each cuvette at the peak absorption wavelength of 633 nm.

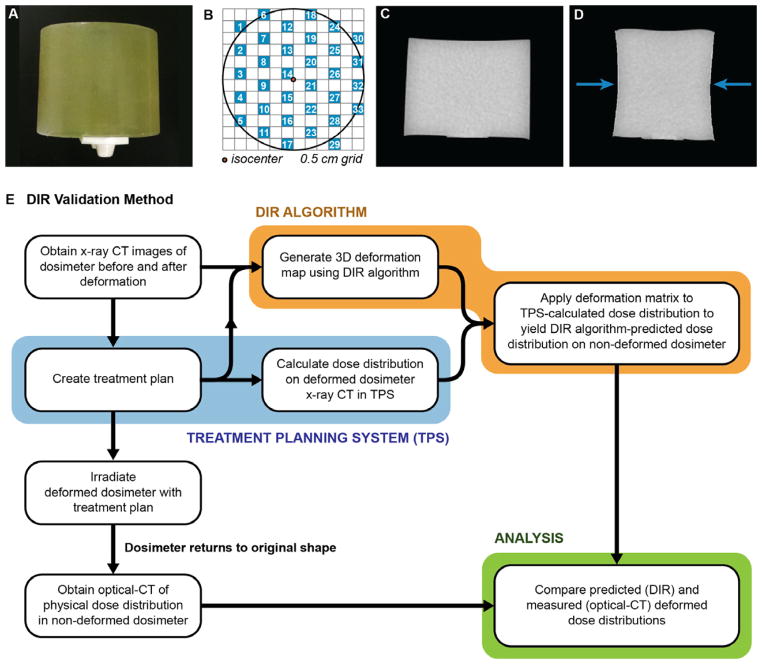

Figure 1.

(A) Photograph of a 6 cm diameter cylindrical Presage-Def dosimeter with attached docking-plate enabling precise registration in the optical-CT scanner. (B) The MLC checkerboard radiation field pattern. 5 mm square radiation fields are shown in blue. (C) Mid-plane CT slice of a dosimeter without compression. (D) Corresponding CT slice of the same dosimeter with compression up to 1.6 cm (27%). Arrows show direction of compression. (E) Flow chart summarizing the method of DIR algorithm validation.

For Presage-Def to be an effective deformable 3D dosimeter, it must have mechanical properties similar to biological tissue. The dosimeter’s polyurethane matrix has a Shore hardness of 10–20A. Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio were measured as these are necessary parameters for biomechanical deformation algorithms (7). Elasticity was determined by subjecting a sample to tensile compression by 30% at 2 mm/min using a Lloyd LRX Plus tensile tester. Young’s modulus was calculated from the resulting stress-strain curve. Poisson’s ratio was determined by calculating the ratio of transverse to axial strain from x-ray CT images taken of a sample with and without applied tension.

Feasibility of dose tracking in a deforming Presage-Def dosimeter was evaluated by irradiating two cylindrical dosimeters with a spaced checkerboard arrangement of 5 mm square beams created by MLC fields (Figure 1B). This pattern formed a grid of clearly identifiable unique dose elements that facilitated visualization of the pattern of spatial deformation throughout the dosimeter similar to pin-cushion distortion mapping. The checkerboard dose pattern allows the distortion field to be unambiguously resolved, as opposed to dose distributions where the distortion field is ambiguous because more than one point can have the same dose value. Both dosimeters were irradiated in air while seated on the table. One dosimeter was irradiated under a simple lateral compression of ~27% (1.6 cm), simulating a deformed organ (Figure 1D). Compression was achieved by placing 6×8×1 cm solid water plates on either side of the dosimeter and applying a clamp to the center of the plates to achieve the desired level of deformation. The plates were removed following irradiation, allowing the dosimeter to return to its original shape. The second dosimeter was irradiated without the deformation mechanism to establish dose distribution in the absence of deformation and provide a comparison point for the distribution in the deformed dosimeter.

High resolution 3D dose distributions were read out from both dosimeters using a telecentric optical-CT scanner recently benchmarked and commissioned for clinical use (19). Dose distributions were reconstructed from 360 projections acquired over 360 degrees. The data was reconstructed at 1 mm isotropic resolution to match the 1 mm calculation grid used in the Eclipse treatment planning system (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). Higher resolution reconstructions are possible if needed (26).

Validation of DIR algorithms

Our method for investigating the accuracy of DIR algorithms is shown in Figure 1E and is similar to that proposed in (15). The method was applied to a commercial DIR software (Velocity Medical Solutions, Atlanta, GA) using the previously described treatment plan (Figure 1B) and deformed dosimeter. This DIR uses a non-biomechanical, multi-resolution modified basis spline (B-spline) algorithm. X-ray CT images of the dosimeter were acquired before and after compression (Figure 1C–D) and imported into the DIR software. The dose distribution in the dosimeter under deformation was calculated in Eclipse and similarly imported into the DIR software. The x-ray CT images were rigidly registered to each other manually and then fine-tuned using the software’s automatic rigid registration. A deformation map was then generated by the DIR algorithm to deform the x-ray CT of the compressed dosimeter back to the shape of the dosimeter without compression. The deformation map was applied to the Eclipse dose distribution to yield the DIR-predicted dose in the uncompressed dosimeter. The accuracy of the DIR-prediction was then evaluated by comparison with the optical-CT measured dose distribution, the latter representing the ground truth of deformation experienced by the dosimeter.

Differences in checkerboard field locations were quantified by determining the centroid of each field in multiple axial cross-sections and evaluating the magnitude of displacement between corresponding fields in the calculated distribution. Field shape differences were quantified in these same axial cross-sections by taking the full width at half maximum (FWHM) for each field along its horizontal (along the axis of compression) and vertical (perpendicular to the axis of compression) profiles. Absolute dose in the dosimeter was obtained by applying the dose sensitivity calibration (Figure 2A). A quantitative dosimetric comparison between measured dose and DIR-predicted dose was then performed by calculating 3%/3mm γ3D passing rate (CERR, Washington University, St Louis, MO). All points receiving dose greater than 5% maximum dose (i.e., 5% threshold) were included in the calculation. A similar analysis was performed on the control non-deformed dosimeter to establish baseline data on the accuracy of the method.

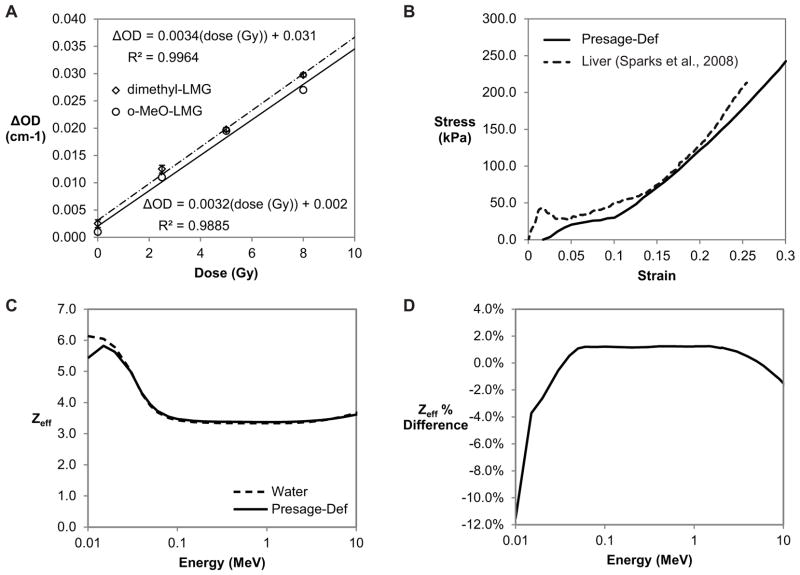

Figure 2.

(A) Presage-Def dose response. (B) Stress-strain curve for Presage-Def determined through tensile compression compared to stress-strain data for human liver under blunt impact compression (27). Young’s modulus is represented by the slope and is stress-dependent. (C) Energy-dependent Zeff values for Presage-Def and water. (D) Percent difference in Zeff values between Presage-Def and water.

RESULTS

Presage-Def characteristics

The dose response of Presage-Def (Figure 2A) demonstrated linear responses (R2=0.9885 and R2=0.9964) with sensitivities of 0.0032 ΔOD/(Gy·cm) and 0.0034±0.0007 ΔOD/(Gy·cm) for the o-MeO-LMG and dimethyl-LMG formulations. These values are substantially lower than regular PRESAGE® (~0.02 ΔOD/(Gy·cm)). The stress-strain curve (Figure 2B) showed a stress-dependent Young’s modulus (stress/strain) and increasing resistance to deformation with increasing applied stress. This is consistent with biological tissues like liver as indicated (27). Young’s modulus ranged from 13.5–887 kPa over a stress range of 0.233–303 kPa. Poisson’s ratio was 0.475 (SE=0.036), which is within the range of literature values for biological tissues (0.450–0.499) (7). Presage-Def was determined to be water equivalent through the power law (Zeff=7.48) and independent verification via Auto-Zeff which confirmed water-equivalence to within 1.5% between 0.03–10 MeV (Figure 2C–D).

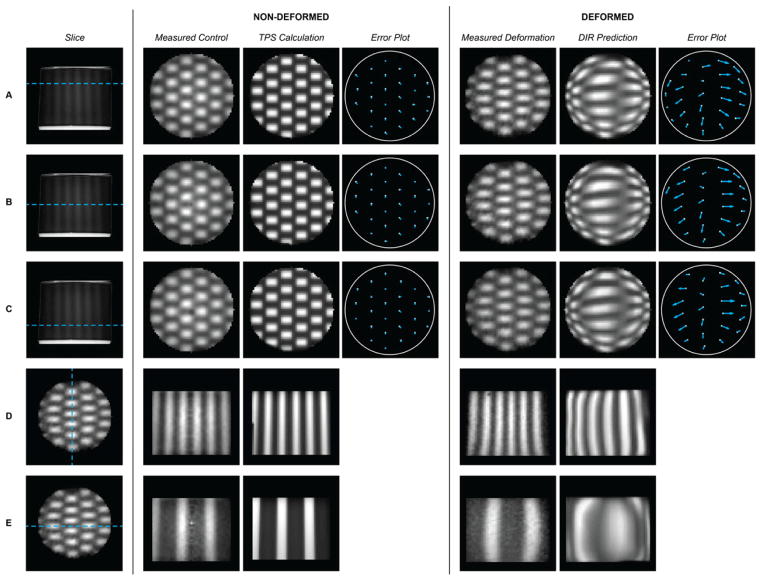

The relative dose distributions in the non-deformed and deformed dosimeters are shown in Figure 3, columns 2 and 5. The measured dose distribution in the deformed dosimeter clearly illustrates that the radiation pattern has tracked with the changing shape of the dosimeter as it returned to its original uncompressed geometry after irradiation. As expected, the checkerboard field dimensions expanded along the axis of compression and contracted along the axis orthogonal to compression.

Figure 3.

Comparison of measured and predicted dose distributions in the control (non-deformed) and deformed dosimeters. In the leftmost column, A–C show a side view projection of the dosimeter indicating the location (depth) of the reconstructed images to the right: (A) Depth=12 mm, (B) Depth=23 mm (central cross-section incurring maximum compression), (C) Depth=34 mm. All data in columns 2–7 are 1 mm isotropic resolution. Error plots indicate the magnitude and direction of the difference between the field centroids in the measured and calculated deformed distributions. Rows (D–E) illustrate orthogonal cross-sections through the dosimeter for completeness.

DIR algorithm validation

The predicted deformed dose distribution from the commercial DIR algorithm is shown in Figure 3 with corresponding quiver plots that quantify the magnitude and direction of the checkerboard displacements (centroid positions of each field) relative to the ground truth measured displacement. Differences between the predicted and actual deformed centroids ranged from 0–9.0 mm with a mean difference of 4.2 mm. The control non-deformed centroid data (Figure 3, column 4) showed much smaller differences of 0–1.4 mm (i.e., variations of no more than 1 pixel) with a mean of 0.8 mm. Minimum, maximum, and mean displacements for each cross-section are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the measured and predicted dose distributions in deformed and non-deformed Presage-Def dosimeters. The nondeformed columns compare Presage-Def measurement and the TPS-calculated dose, and the deformed columns compare Presage-Def measurement and the DIR prediction. Cross-sections are at depths of 12 mm (A), 23 mm (B), and 34 mm (C) as shown in Figure 3. Centroid displacement quantifies field location differences while the horizontal and vertical FWHM quantify field shape differences. All centroid displacement values are absolute. The minimum, maximum, and mean errors across all 3 cross-sections are summarized as Overall. There is an uncertainty of ±1 mm on all measurements due to the 1 mm isotropic resolution used.

| Cross-Section | Non-Deformed

|

Deformed

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centroid Displacement (mm) | Horizontal FWHM Difference * (mm) | Vertical FWHM Difference * (mm) | Centroid Displacement (mm) | Horizontal FWHM Difference * (mm) | Vertical FWHM Difference * (mm) | ||

| A | Minimum | 0.0 | −2 | −2 | 0.0 | −5 | −2 |

| Maximum | 1.4 | 1 | 1 | 7.3 | 9 | 1 | |

| |Mean| | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 0.6 | |

|

|

|||||||

| B | Minimum | 0.0 | −2 | −2 | 2.0 | −6 | −2 |

| Maximum | 1.4 | 1 | 1 | 7.3 | 14 | 2 | |

| |Mean| | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 0.6 | |

|

|

|||||||

| C | Minimum | 0.0 | −2 | −2 | 2.0 | −6 | −2 |

| Maximum | 1.4 | 1 | 1 | 9.0 | 10 | 1 | |

| |Mean| | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 0.6 | |

|

| |||||||

| Overall | Minimum | 0.0 | −2 | −2 | 0.0 | −6 | −2 |

| Maximum | 1.4 | 1 | 1 | 9.0 | 14 | 2 | |

| |Mean| | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 4.2 | 3.8 | 0.6 | |

FWHMcalculated − FWHMmeasured

Large differences were seen in individual checkerboard field shapes between the measured and predicted deformed distributions (Figure 3, columns 5–6). These differences are quantified in Table 1. The predicted horizontal FWHM varied from 6 mm narrower to 14 mm wider than the measured fields. The vertical FWHM varied from 2 mm shorter to 2 mm taller than the measured fields. The baseline control data yielded average absolute errors of 0.7 mm in field width and 0.8 mm in field height (i.e., within 1 pixel). All measurements are subject to ±1 mm uncertainty due to the 1 mm isotropic resolution used. The largest errors were all observed in cross-section B, the region of maximum deformation. Magnitude of centroid displacement did not correspond with differences in field shape. This is demonstrated in the case of field 13 (Figure 1B) in cross-section B (Figure 3B, columns 6–7): the DIR-predicted distribution exhibited a relatively small centroid location error (2.2 mm) for this field, but generated the largest field shape error (14 mm) seen within this sample.

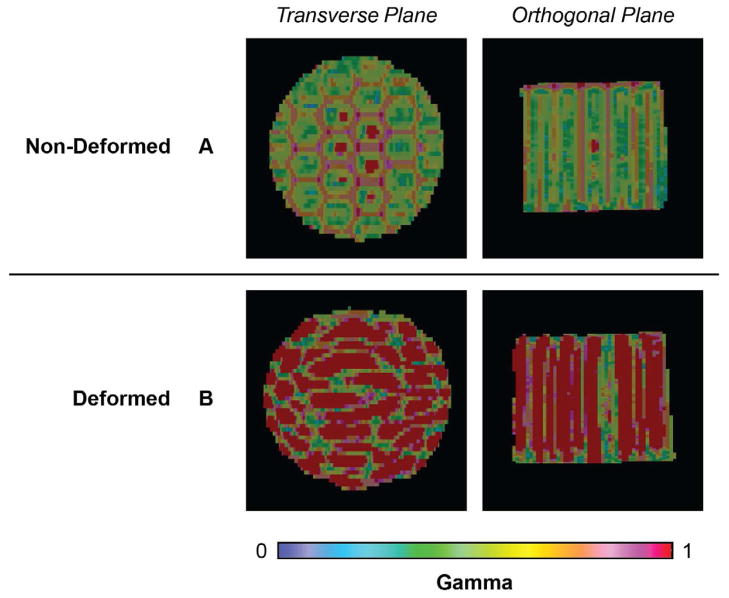

The 3D gamma analysis yielded a more comprehensive view of the measured and predicted dose distributions in both control and deformed cases. The non-deformed control yielded good agreement between the measured and predicted dose distributions with a γ3D passing rate of γ3%/3mm=96.4% (Figure 4A). The deformed dosimeter yielded a γ3D passing rate of only γ3%/3mm=60.0% (Figure 4B). Failing regions in the DIR-predicted distribution occur throughout the dosimeter volume.

Figure 4.

γ3D maps (3%/3mm criteria with 5% threshold). (A) Non-Deformed: Comparison between measured and Eclipse dose distributions in the non-deformed control dosimeter. (B) Deformed: Comparison between the measured and DIR predicted dose distributions in the deformed dosimeter. Transverse maps are located in the region of maximum compression. All failing gamma values (≥1) are displayed in red to aid visualization.

DISCUSSION

These results demonstrate that Presage-Def is able to integrate dose in different states of deformation and can be used as a validation method to investigate the accuracy of DIR algorithms. Furthermore, substantial errors were detected in a commercial DIR algorithm in the scenario studied, indicating strong caution must be applied when using these algorithms in a clinical context. The results speak to the recent controversy in this regard (1). The Velocity DIR successfully deformed external contours, but the accuracy of dose deformation would likely be improved if the user had access to vary the deformation algorithm parameters (2, 15).

Other efforts have been made toward the development of deformable 3D dosimeters for DIR validation. Presage-Def has several potential advantages, including the lack of requirement for an external container, thereby simplifying the mechanics of deformation; robustness to the environment (i.e., no desensitization in the presence of atmospheric oxygen); no diffusion of radiochromic signal; and amenability to accurate and fast optical-CT imaging because the optical contrast is created by light-absorbing dye molecules rather than light-scattering particles (28).

Tensile data for Presage-Def demonstrates elastic properties similar to that of biological tissues, indicating that Presage-Def has promise as an anthropomorphic phantom material. Young’s modulus is highly dependent on the method of deformation (29), therefore further tensile testing may be required to directly compare with specific tissues of interest. The close agreement of Presage-Def stress-strain data with liver (Figure 2D) suggests the possibility of matching Presage-Def mechanical properties to specific tissues.

The checkerboard pattern was specifically designed to quantify deformation-induced distortion throughout the dosimeter volume. As shown in Figure 3, the irradiation pattern in the deformed dosimeter demonstrated dose tracking consistent with the dosimeter’s physical deformation. The high γ3D passing rate in the control condition (96.4%) (Figure 4A) demonstrated Presage-Def’s capability for accurate quantitative 3D dosimetry.

In the homogenous cylinder scenario studied, considerable inaccuracies were detected in the predicted deformed dose distribution from the commercial DIR. The lack of internal structure in the dosimeter renders this a modestly challenging deformation with relevance to tissue structures containing regions of significant homogeneity (e.g., liver). The commercial DIR did perform well in deforming the external contours of the dosimeter, with the deformed contours matching the edge of the dosimeter with sub-millimeter accuracy. This is to be expected as the contrast at the edge of the dosimeter is very high. The substantial errors in the predicted deformation within the dosimeter (Figure 3, columns 6–7, and Figure 4) were a surprise. Intensity-based deformable image registration algorithms (like that used by VelocityAI) rely on matching fairly closely spaced heterogeneous intensity features. In our case, however, the deformable dosimeter was homogeneous, with heterogeneous features confined to the boundaries. This scenario is especially challenging for these DIR algorithms. It is possible that biomechanical DIR algorithms which incorporate elastic properties of the material may perform better in this scenario. This is the subject of future work.

CONCLUSIONS

This work introduces a novel Presage-Def/Optical-CT deformable 3D dosimetry system suitable for investigating the accuracy of DIR algorithms applied to dose-warping. Presage-Def is tissue equivalent with elastic properties similar to liver tissue and facilitates accurate, high resolution (1 mm isotropic) 3D dosimetry. A cylindrical, homogeneous Presage-Def dosimeter (6 cm diameter, 4.75 cm length) with no internal features was employed to investigate a commercial DIR algorithm, and highlighted the potential for substantial errors (Figures 3–4). These results highlight the critical necessity of validating DIR algorithms prior to clinical implementation to ensure patient safety and quality of care.

Summary.

Accurate deformable image registration (DIR) is essential to achieving full potential for adaptive radiation therapy and treatment response assessment. The lack of comprehensive methods for verifying DIR algorithms is currently limiting clinical implementation. This study introduces a novel deformable 3D dosimetry system (Presage-Def/Optical-CT) and its application to the verification of a commercial DIR algorithm. Results demonstrate substantial errors may occur and highlight the critical need for DIR validation prior to clinical implementation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01CA100835. We thank Patrick McGuire of the Duke University Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science Department for his help with tensile measurements.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Notification

John Adamovics is president of Heuris Inc, which commercializes Presage.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schultheiss TE, Tome WA, Orton CG. It is not appropriate to “deform” dose along with deformable image registration in adaptive radiotherapy. Medical Physics. 2012;39:6531–6533. doi: 10.1118/1.4722968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor ML, Yeo UJ, Kron T, et al. Comment on “It is not appropriate to ‘deform’ dose along with deformable image registration in adaptive radiotherapy” [Med. Phys. 39, 6531–6533 (2012)] Medical physics. 2013;40:017101. doi: 10.1118/1.4771962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brock KK, McShan DL, Ten Haken RK, et al. Inclusion of organ deformation in dose calculations. Medical Physics. 2003;30:290. doi: 10.1118/1.1539039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorbunova V, Sporring J, Lo P, et al. Mass preserving image registration for lung CT. Medical image analysis. 2012;16:786–95. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang D, Li H, Low Da, et al. A fast inverse consistent deformable image registration method based on symmetric optical flow computation. Physics in medicine and biology. 2008;53:6143–65. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/21/017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu W, Chen M-L, Olivera GH, et al. Fast free-form deformable registration via calculus of variations. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2004;49:3067–3087. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/14/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brock KK, Sharpe MB, Dawson La, et al. Accuracy of finite element model-based multi-organ deformable image registration. Medical Physics. 2005;32:1647. doi: 10.1118/1.1915012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brock KK. Results of a multi-institution deformable registration accuracy study (MIDRAS) International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2010;76:583–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kashani R, Hub M, Balter JM, et al. Objective assessment of deformable image registration in radiotherapy: A multi-institution study. Medical Physics. 2008;35:5944. doi: 10.1118/1.3013563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thornqvist S, Petersen JBB, Hoyer M, et al. Propagation of target and organ at risk contours in radiotherapy of prostate cancer using deformable image registration. Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden) 2010;49:1023–32. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.503662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kabus S, Klinder T, Murphy K, et al. Evaluation of 4D-CT lung registration. Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention: MICCAI … International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. 2009;12:747–54. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-04268-3_92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh A, Battista J, Jordan K. Developing Deformable 3D Dosimeters: Radiochromic Gels in Latex Balloons. Medical Physics. 2011;38:3728. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niu CJ, Foltz WD, Velec M, et al. A novel technique to enable experimental validation of deformable dose accumulation. Medical Physics. 2012;39:765–76. doi: 10.1118/1.3676185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeo UJ, Taylor ML, Dunn L, et al. A novel methodology for 3D deformable dosimetry. Medical physics. 2012;39:2203–13. doi: 10.1118/1.3694107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeo UJ, Taylor ML, Supple JR, et al. Is it sensible to “deform” dose? 3D experimental validation of dose-warping. Medical physics. 2012;39:5065–72. doi: 10.1118/1.4736534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandecasteele J, De Deene Y. On the validity of 3D polymer gel dosimetry: III. MRI-related error sources. Physics in medicine and biology. 2013;58:63–85. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/1/63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oldham M, Siewerdsen JH, Shetty A, et al. High resolution gel-dosimetry by optical-CT and MR scanning. Medical Physics. 2001;28:1436. doi: 10.1118/1.1380430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosi S, Naseri P, Puran A, et al. Initial investigation of a novel light-scattering gel phantom for evaluation of optical CT scanners for radiotherapy gel dosimetry. Physics in medicine and biology. 2007;52:2893–903. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/10/017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas A, Newton J, Adamovics J, et al. Commissioning and benchmarking a 3D dosimetry system for clinical use. Medical Physics. 2011;38:4846. doi: 10.1118/1.3611042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas A, Newton J, Oldham M. A method to correct for stray light in telecentric optical-CT imaging of radiochromic dosimeters. Physics in medicine and biology. 2011;56:4433–51. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/14/013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakhalkar HS, Adamovics J, Ibbott G, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of the PRESAGE/optical-CT 3D dosimetry system. Medical Physics. 2009;36:71. doi: 10.1118/1.3005609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alqathami M, Blencowe A, Qiao G, et al. Optimization of the sensitivity and stability of the PRESAGETM dosimeter using trihalomethane radical initiators. Radiation Physics and Chemistry. 2012;81:867–873. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juang T, Newton J, Niebanck M, et al. Customising PRESAGE® for Diverse Applications. IC3DDose 2012 – 7th International Conference on 3D Radiation Dosimetry; Sydney, Australia. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo PY, Adamovics JA, Oldham M. Characterization of a new radiochromic three-dimensional dosimeter. Medical Physics. 2006;33:1338. doi: 10.1118/1.2192888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor ML, Smith RL, Dossing F, et al. Robust calculation of effective atomic numbers: the Auto-Z(eff) software. Medical physics. 2012;39:1769–78. doi: 10.1118/1.3689810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newton J, Oldham M, Thomas A, et al. Commissioning a small-field biological irradiator using point, 2D, and 3D dosimetry techniques. Medical physics. 2011;38:6754–62. doi: 10.1118/1.3663675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sparks JL, Dupaix RB. Constitutive modeling of rate-dependent stress-strain behavior of human liver in blunt impact loading. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2008;36:1883–92. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9555-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldock C, De Deene Y, Doran S, et al. Polymer gel dosimetry. Physics in medicine and biology. 2010;55:R1–63. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/5/R01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKee CT, Last JA, Russell P, et al. Indentation Versus Tensile Measurements of Young’s Modulus for Soft Biological Tissues. Tissue Engineering. 2011;17:155–164. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2010.0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]